2015 Volume 123 Issue 1 Pages 1-12

2015 Volume 123 Issue 1 Pages 1-12

This paper describes a human skeleton from a rock-shelter in northeast Laos, dated to ~7000 BP. It was excavated in 2004 and moved en bloc to the Laos National Museum in Vientiane. Here we report observations made from the in situ skeleton. The burial is the largely complete but slightly damaged remains of a tall, middle-aged, probable male buried on his side in a flexed position. His teeth were heavily worn and one was infected but otherwise there is no evidence of poor health. We were not able to make an assessment of biological affiliation. In comparison with the very small samples of approximately contemporary skeletal remains from the wider region around the middle Mekong, it is clear that the burial position and dental health were not unusual, but that he was very tall for that period of prehistory.

An adult skeleton was found in 2004 in a rock-shelter in the Pha Phen karst, Khamkeut District, Bolikhamsay Province, Lao People’s Democratic Republic (Figure 1). Several rock-shelters and caves in the region were being surveyed by a group of archaeologists from the Department of Museums and Archaeology, Ministry of Information and Culture of Laos, in advance of the construction of a dam as part of the Nam Theun II Power Project. After excavation, the skeleton was moved en bloc to the Laos National Museum, Vientiane. The skeleton is to be exhibited in the Museum and the Nam Theun II Power Company, who provided the funding, required that it be retained in its original position for this purpose. This paper is a description of the skeleton and the individual it represents, as far as could be ascertained by observation of the bones in situ at the Museum in early 2012, together with an assessment of the significance of the evidence from this individual in a human biological context.

Southeast Asia showing the location of Pha Phen and comparative skeletal samples.

The archaeological excavation of the burial has been described by Sayavongkhamdy and Souksavatdy (2008). The following is derived from that publication. The skeleton was in a flexed position (Figure 2) and the burial was described as Neolithic, based on this burial practice (Sayavongkhamdy and Souksavatdy, 2008: 26). An AMS radiocarbon date from Beta Analytic of 6910 ± 40 BP (95%) cal. 7180–7010 BP (68%), using the INTCAL98 calibration curve (Stuiver and van der Plicht, 1998), was obtained from a fragment of femoral cortical bone. There was no material culture directly associated with the burial. Although there were nine 1 m × 1 m test squares opened in the same rock-shelter, with butchered animal bones and sherds of cord-marked pottery identified as Neolithic style being found, these were not associated with the burial. Nearby, two other rock-shelters contained a variety of artefacts, including conchoidal flakes and polished stone tools described by Sayavongkhamdy and Souksavatdy, (2008) as “possible Palaeolithic,” together with a range of other artefacts such as cord-marked pottery sherds, shell and glass beads, and butchered animal bones, suggesting a long period of use of the shelters lasting until late prehistory. Aside from the radiocarbon date, we have no unequivocal evidence of the cultural context of the Pha Phen burial within this long period of occupation of the rock-shelters. We also discuss further the issue of the imprecision introduced by the application of categories such as ‘Neolithic’ to Southeast Asian archaeological contexts in the section on the context of the Pha Phen burial later in this paper.

The skeleton showing the position of burial.

During the fieldwork, following exposure of the skeleton, wooden boxing was built to support a block of soil around the burial, measuring approximately 1 m × 1 m. The surrounding area had been excavated approximately 40 cm below the burial and the block undercut from all sides, leaving a central pedestal. Reinforcing rods were inserted under the pedestalled block, with further boxing built and concrete poured to form a solid support. The skeleton was covered in a layer of plastic and several layers of plaster poured over the plastic. The block (Figure 3) was then lifted from the rock ledge using a crane, loaded on to a truck and transported to the Laos National Museum in Vientiane.

The block containing the plastered skeleton ready for removal from the site.

The analysis was carried out in 2012 by N.T. and S.H. at the Museum. The first stage was to expose the skeleton again, which was achieved by removing the plaster at the margins of the block using hammer and chisel. Once this was removed, it was possible to lift of the remainder of the plaster; although the layer of protective plastic had deteriorated since the excavation, it nevertheless protected the bones sufficiently for the plaster to be lifted from areas of the skeleton, leaving the bones exposed. We carried out further minor excavation to expose the skeleton fully and recorded the bones present, their condition, and the position of the skeleton. We constructed an ‘osteobiography’ of the person represented. This involved estimation of sex and age at death, recording of the few measurements that were possible, and recording evidence of health.

The skeleton is that of an adult, buried in a flexed position, lying on the right side with the knees drawn up and the arms crossed (Figure 2). The cervical spine is flexed to the anterior and the right, the skull overlying the right shoulder, and facing inferiorly. The position of the left shoulder is not clear as it has been damaged. The left humerus is partly flexed at the shoulder joint and resting on the left rib cage with the elbow over the spine. Both elbows are flexed at right angles with the forearms across the body. The left hand is resting on the distal third of the right humerus and the right hand either lost postmortem or not visible under the left forearm. The vertebral column is rotated to the right but mostly not visible under the left upper limb. The ribs on both sides are mostly present. The pelvis is lying with the left ilium uppermost. The hip and knee joints are tightly flexed with the knees drawn up towards the right elbow. The left femur has rotated laterally along the long axis so the head is dislocated from the acetabulum, a movement that could have occurred into the space created by the decomposition of the soft tissues when it would have no longer been supported in its uppermost position in the grave. The feet are dorsiflexed, and the left foot is lying over the right foot. The position of the pelvis and the feet suggest that the grave was oval shaped with the pelvis and feet resting against the left side of the grave. It is possible that the body was wrapped so that it fitted in the grave, and the decomposition of the wrapping also removed support from the left femur, permitting its dislocation at the hip joint.

The bones are almost all represented, although some have damage at the extremities so they would not be complete if removed from the ground. The cranium has been crushed and partly fragmented from tree roots growing through the calvarium, although it appears most of the vault is present. The face is mostly present but only the left side is visible. The right side of the mandible is pressed against the right clavicle, with the body broken postmortem at the left premolars and forced away from the maxilla. The position and postmortem damage of the skull, with only partial visibility of both cranium and mandible, precluded taking any measurements. The left shoulder, the knees, and the left pelvic bone have suffered the most damage, either in prehistory or during the excavation. Most of the spine, some ribs, right shoulder, left scapula right hand, and proximal right femur are obscured by overlying bones. The left hand is missing seven of fourteen phalanges. There were two loose phalanges with the skeleton but it is not clear whether these are from the left or right hand. Otherwise the only visible bones of the right hand are a few carpals. The right foot is missing all phalanges, and the left foot missing two metatarsals and all phalanges except the first proximal.

The bone tissue is hard and all surfaces have adhering concretions of unknown composition but we assume formed from minerals in the burial matrix. On much of the skeleton, the concretion is light and stained brown from the overlying burial matrix. In some areas the concretion is heavier, mainly in discrete nodules. A piece of bone from the posterior distal shaft of the right femur was taken by the excavators for radiocarbon dating.

Estimation of sex was based on the skull, as most of the pelvis is either damaged or obscured. The right greater sciatic notch is partly visible and appears to be either grade 3 (neutral) or possibly grade 4 (? male) (Buikstra and Ubelaker, 1994: 18). The skull features visible were graded using the scale detailed in Buikstra and Ubelaker (1994: 20). The left supraorbital is grade 3, left orbital rim grade 2–3, left mastoid process grade 3–4, and the chin grade 4–5. On balance the skull features suggest male. The only evidence from the postcranial skeleton is the left femur head diameter, at 44.6 mm, and the distal right epicondylar breadth at 60.1 mm, which are just above the section point of more recent prehistoric Southeast Asian skeletons, suggesting sex was male (Kate Domett, personal communication). The fact that the measurements were at the lower end of the male range suggests he was slender. The maximum femur length at 478 mm is well above the male/female section point of ~426 mm (Kate Domett, personal communication). Taking all features into consideration, the best estimate of sex is ‘probable’ male. Using the available stature estimation equations from Thai individuals, the dimensions suggest that he was tall for a prehistoric Southeast Asian, at 175.56 ± 3.50 cm (Sangvichien et al., 1985) or 174.4 ± 4.06 cm (Pureepatpong et al., 2012).

Age at death is more difficult to estimate, as the visible evidence is minimal. The pubic symphyseal surfaces are obscured but a small area of the auricular surface of the right ilium is visible and has features (a coarsely granular surface, some macroporosity) that suggest approximately phase 6 (Buikstra and Ubelaker, 1994: 25, derived from Lovejoy et al., 1985). As there is no evidence that the absolute ages ascribed to these phases are applicable to Southeast Asians, the best estimate that can be made is that the man was neither a young adult nor an old man, so most likely in the middle years of adulthood. We have not used the only other potential indicator of age, wear on the dentition, because of its extreme condition, described below.

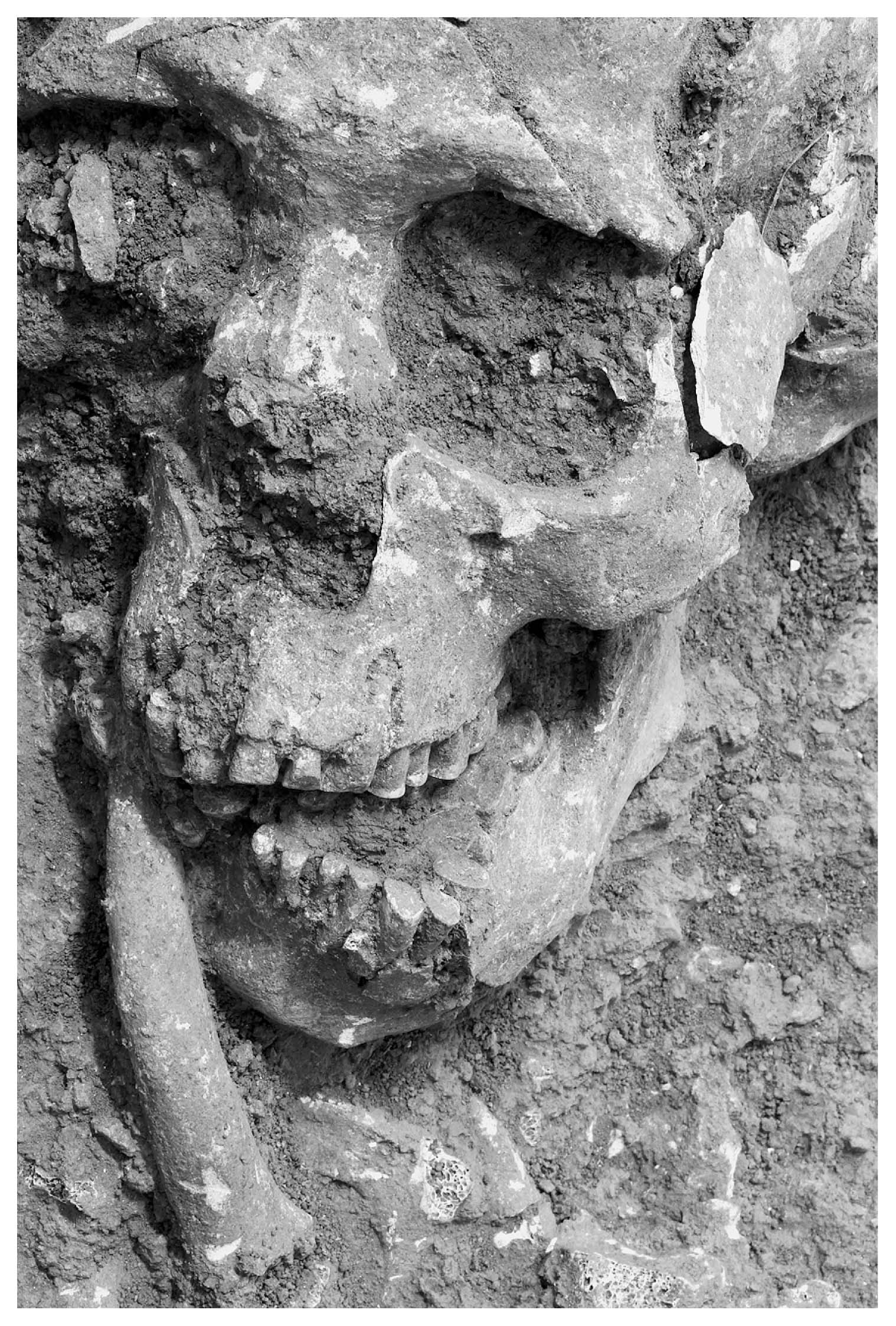

The most common pathologies seen in skeletal remains are dental and articular. In Pha Phen, the most informative aspect of health is the dentition. The visible teeth (Figure 4) are almost exclusively on the left side, where all teeth, including third molars, are present in both maxilla and mandible. The right mandibular incisors are also visible. The most striking aspect of the dentition is unusual wear, with the occlusal wear very heavy on the anterior mandibular teeth (left and right incisors, left canine and premolars) and the maxillary left incisors and canine (grades 7–8: Buikstra and Ubelaker, 1994: 52, derived from Scott, 1979). Most of these teeth have such severe wear that the crowns have been removed and the roots are functioning as the occlusal surfaces. Despite this, there is no visible exposure of the pulp cavities. This suggests the wear occurred slowly enough for secondary, or possibly tertiary, dentine to maintain the integrity of the occlusal surface (Simon et al., 2013). The wear on both maxillary and mandibular left canines and lateral incisors is angled lingually, although the wear on the maxillary left central incisor is flat. This pattern is unusual and suggests some process other than normal occlusal forces during mastication but the angled wear surfaces are smooth with no visible striations or grooves that might indicate industrial or task-related wear. The left maxillary premolars are slightly less heavily worn (grade 6: Buikstra and Ubelaker, 1994: 52, derived from Smith, 1984). The mandibular molars are also very severely worn with little enamel remaining (grade 36: Buikstra and Ubelaker, 1994: 53, derived from Scott, 1979) but, as with the premolars, the wear on maxillary molars is not quite as severe (grades 22–26). There are no visible caries, and minimal calculus but this could have either been removed during excavation or be obscured by concretions. The alveolar processes are partly damaged but the crest appears to have been resorbed to some extent and although concretions prevent quantification of this, it suggests that he had periodontal problems. There is a cavity in the bone around the root of the left maxillary canine, suggesting an active apical infection, perhaps a chronic abscess on the tooth. This cavity is filled with concretion so it is not possible to diagnose its exact nature (Dias and Tayles, 1997). The concretions obscuring the tooth surfaces prevented assessment for developmental defects in the form of enamel hypoplasia or hypomineralization that may be indicative of growth disruption, and therefore episodic ill health, during infancy or childhood.

The dentition, showing the extreme occlusal wear on the anterior teeth.

The articular surfaces of the bones are mostly obscured, with none completely visible but there is slight degeneration in the form of marginal osteophytes visible on one of the lumbar vertebrae, suggesting early disc degeneration. There is no evidence of any other skeletal pathology such as healed fractures, other trauma, infection, or inflammation.

To place Pha Phen in context, we consider comparative samples of human skeletal remains from the approximately contemporary period of prehistory, around 15000–5000 BP. The identification of the chronology of the skeletal remains reviewed here has included a wide variety of definitions of periods of prehistory, including attribution to the Palaeolithic/Mesolithic/Neolithic cultural periods. This terminology has implications for the attributes of the societies to which these individuals belong, such as whether or not their subsistence economy included farming of domesticated animals and plants, what type and sophistication of stone tool technology they employed, and whether or not they were living in sedentary communities. As many of the remains have little or no archaeological context, or the interpretation of the context for samples excavated/collected in the early 20th century is outdated, these Eurocentric terms cannot be sensibly applied to these samples. One alternative, also frequently employed, uses the geological periods of Pleistocene/Holocene but these geological timescales lack precision. The definition of ‘early’ or ‘mid’ Holocene, for example, varies among researchers. We have therefore made efforts to use absolute dates, where available, in our attempts to place Pha Phen with contemporary skeletal remains. This, of course, has its own problems with the questions about older dates in particular, including the validity and relevancy of the material used for dating, and whether or how they have been calibrated or replicated. It also implies that the populations to which the small samples belonged were culturally and economically similar, which may not be the case. We are not implying this and our findings must be interpreted with this caveat.

The availability of skeletal samples from Southeast Asia reflects the history of the region, which has had a differential effect on the archaeology of modern political states. The development of modern archaeology in the Lao People’s Democratic Republic was constrained by the political and economic situation until the 1990s so relatively little is known about bioarchaeology of prehistoric peoples of central Laos compared with the neighbouring areas of Vietnam and northeast Thailand. We therefore define the context as the wider region around the middle Mekong Valley, beyond its watershed to the west in northern Thailand and east in northern Vietnam. Rivers, and in relation to Pha Phen, the Mekong, would have had the potential to be major conduits for movements of people, languages, and cultures (White and Bouasisengpaseuth, 2008: 39). Despite the fact that the watersheds of northern and western Thailand (Salween and Chao Praya Rivers) and northern Vietnam (Red and Ma Rivers) are separated from each other and the Mekong by ridges of varying terrain that would presumably have created barriers to contact between populations and contributed to the cultural and linguistic diversity seen even today, the tiny number of samples of human skeletal remains available means our comparison must include those from the wider region. These are summarized in Table 1. Ideally, we would include the region to the north on the Mekong River, in China, but have found no accessible published evidence of relevant samples from the vicinity.

| Location: River valley | n | Dating (’000 BP) | Sex estimate | Age at death estimate | Burial position | Source | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pha Phen | Central Laos: Mekong | 1 | 10 | Male | Middle age? | Flexed, lying on the side | |

| Ban Dang | Central Laos: Mekong | 1 skull | — | — | — | — | Pietrusewsky, 1981: 2 |

| Tam Hang | North Laos: Mekong | 17: of which 10 remain | 16 | 2 × male 2 × female 1 × adult |

One male aged “20 years+”, others no age estimate | Three supine, no indication which three One extended (landslide victim?) | Fromaget and Saurin, 1936 Shackelford and Demeter, 2012 |

| Tam Pong | North Laos Mekong | 1 skull | Female | — | Squatting/crouched on back | Fromaget and Saurin, 1936 Shackelford and Demeter, 2012 | |

| Lang Cuom | North Viet Nam: Red | Many: 12 skulls1 5 skulls2 |

— | — | — | 1Mansuy and Colani, 1925; 2Pietrusewsky and Douglas, 2002; Shackelford and Demeter, 2012 | |

| Lang Gao | North Viet Nam: Red | 20 skulls | — | — | — | Colani, 1927a, b | |

| Keo Phay, Kha Khiêm, Pho Binh Gia, Dong Thuôc Cau Giat Dong Can | North Viet Nam: Red | 1 skull at each site | — | — | — | Mansuy, 1924; Mansuy, 1925a, b; Colani, 1930; Pietrusewsky and Douglas, 2002; Matsumura et al., 2001; Shackelford and Demeter, 2012 | |

| Sao Dong, Som Jo | North Viet Nam: Red | 1 each, maxilla, mandible | — | — | — | Colani, 1927b | |

| Hang Cho | North Viet Nam: Red | 1 | 10 | Female | Old | Supine, knees flexed | Matsumura et al., 2008 |

| Mai Da Nuoc | North Viet Nam: Red | 1 | 10–8 | Male | Old | Extended/supine | Nguyen, 1986; Matsumura, 2006 |

| Con Co Ngua | 94 | 6–5 | Oxenham, 2000; Oxenham et al., 2006 | ||||

| Tham Lod | North Thailand Salween | 2 | 12–13 | 1: — 2: Female |

Adult Old |

Flexed on side Extended/supine |

Pureepatpong, 2006; Shoocongdej, 2006 |

| Ban Rai | North Thailand Salween | 1 | 10 | Male | 45–50 years | Supine, knees flexed, neck flexed forward | Pureepatpong, 2006; Shoocongdej, 2006 |

| Ban Tha Si | North Thailand Chao Phraya | 1 | 7+ | Male | — | Flexed on side, knees tightly flexed | Zeitoun et al., 2013 |

| Sai Yok | West Thailand Chao Phraya | 1 | 10–4 | Female | ~20 years | Supine, knees flexed | Jacob, 1969 |

The only human skeletal remains approximately contemporary with Pha Phen that have been reported from the modern state of Laos, and from the Mekong watershed, include a small number found during early 20th century excavations at a series of sites by French researchers working with the Geological Survey of Indochina. Some of these are now curated at the Musée de l’Homme, Paris. The only sample from the vicinity of Pha Phen is a skull provenanced from a site, Ban Dang, located in the same region as Pha Phen in central Laos (Pietrusewsky, 1981: 2). Unfortunately nothing is known of its context or dating. Two other sites further west in Laos with samples are cave/rock-shelters, Tam Hang and Tam Pong (Fromaget and Saurin, 1936) (see Pietrusewsky, 1981: 2; Shackelford and Demeter, 2012: 99 for details of crania from these sites and others in Vietnam). The timing of the French excavations and the minimal published descriptions means no reliable dating was available until recently. During renewed research on the site of Tam Hang, a C14 date of c. 16000 BP was obtained from one of the skeletons, which are described as being all in the same level of the site (Demeter, 2000: 146). This places Tam Hang earlier than Pha Phen. Demeter (2000: 138) provides a C14 date of 5380 ± 60 BP for Tam Pong, making it closer to, but later than, Pha Phen.

The historic French expeditions led by Henri Mansuy and Madelaine Colani, also excavated or recorded human skeletal remains from caves and rock-shelters in neighbouring Vietnam, in the northeast of the country. They attribute these remains variously to Neolithic, Mesolithic, or Palaeolithic, or Hoabinhian or Bacsonian (Mansuy, 1924; Mansuy and Colani, 1925; Mansuy, 1925a, b, c; Colani, 1927a, b, 1930) on the basis of stratigraphic relationships or associated material culture. There appears to be no universal agreement on whether Hoabinhian and Bacsonian refer to different time periods or different cultures (Higham, 2002: 35). For our purposes, they are approximately contemporary. There are no doubt other publications describing human skeletal remains in the series ‘Contribution a l’etude de la prehistoire de l’Indochine’ to which most of the above publications belong, but we have not had access to all volumes.

Some of the remains reported are represented by as little as a single skull fragment, others are estimated to represent a large number of individuals but were disturbed and commingled. Mansuy and Colani (1925) estimate at Lang Cuom 80–100 individuals were represented, mixed with midden and lithics. They refer to twelve crania in this collection. Mansuy (1925b) describes finding large numbers of bones accumulated as an ossuary accumulated up to 50 cm in depth, some incorporated in limestone, in a small cave at Ham-Rong but apparently no complete or near-complete skulls and no description has been provided. Colani (1927a, b) describes twenty crania from a rock-shelter site at Lang Gao. The skulls had been placed upright, resting on the occipital and maxilla. Four had adjacent unworked limestone blocks that were possibly originally supporting the skulls. All were heavily encrusted with limestone and are described as being embedded in the underlying matrix. There was an unspecified quantity of disarticulated postcranial remains, mainly long bones, close to the skulls, and Colani (1927a: 228) interprets the remains as evidence of secondary burials. At other sites in the vicinity, Keo Phay and Khac Kiêm, Mansuy (1925a, b) describes single, mostly fragmentary, skulls. At Dong-Thuoc, Mansuy (1924: 15–16) describes fragmentary and fossilized bones of two individuals at one level, and at a deeper level an undisturbed skeleton with a relatively complete skull and at least some, incomplete, long bones. Mansuy (1925c: 9) refers briefly to three skulls from Pho Binh Gia (citing Verneau, 1909). Colani (1927b) illustrates a “tres petit” partial maxilla and two long bone shafts from the site of Sao-Dong (p. 18; plate III) and a large, fragmented mandible from Som-Jo (p. 47, plate X). Colani (1927b) refers to fragmented finds of human skeletal remains from other sites but without illustrations or detailed descriptions, these are not of value here.

The dating of these sites remains problematic but they all appear to be pre-metal. Pietrusewsky and Douglas (2002: 223) refer to seven individuals from three sites (Dong Thuoc, Pho Binh Gia, Lang Cuom) as “probably dating to the early-mid Holocene.” Shackelford and Demeter (2012) date these three sites and an additional two (Cau Giat and Dong Can; citing Colani, 1930) to 7500 BP, although the basis for this dating is not stated and sample sizes not given in this paper. Cau Giat is listed as also having postcranial remains (Shackelford and Demeter, 2012). Matsumura et al. (2001: 62) refer to “Bac Son Early Neolithic” samples including Lang Cuom and Pho Binh Gia plus Khac Kiem and Keo Phay. Matsumura and Hudson (2005: 187) describe them as “Early Holocene Hoabinhian and Bacsonian cultures” dated c. 10000–6000 BP. The focus of early publications on these skeletal remains is the description and attribution traditionally to ‘race’ with little or no description of other characteristics of the skeletons, particularly the postcranial bones, or the nature of their interment. Essentially, the skulls were treated in the same way as material culture, particularly stone tools, with the aim of allocating them into discrete morphological groups. The recent publications are restricted to the skulls curated in the Musée de l’Homme, and are focussed on analysis of biological relationships based on cranial or dental morphology.

Skeletal remains found more recently are from Mai Da Dieu and Mai Da Nuoc, further south but still in north Vietnam, excavated by Vietnamese archaeologists and dated to c. 8000–10000 BP (Nguyen, 1986; Matsumura, 2006) and Hang Cho, dated to 10000 BP (Matsumura et al., 2008). With the exception of Hang Cho, these papers report on cranial and dental remains only. Although the Mai Da Nuoc individual was found with postcranial bones, no description is available (Nguyen, 1986). These individuals may well be contemporary with Pha Phen.

South of these sites but still in north Vietnam is the site of Con Co Ngua, excavated more recently by Vietnamese archaeologists (Oxenham et al., 2006). This has reliable dates of 6000–5000 BP and has a large sample (n = 94) but is again not in the Mekong region and its coastal location may mean that the inhabitants had a very different subsistence regime from inland peoples, such as at Pha Phen.

In the other direction, towards the west, there have been a few late Pleistocene/early Holocene skeletons found recently. In the northern Thailand province of Mae Hong Son, in the drainage basin of the Salween River very close to the Burmese border, excavations were conducted in 2001–02 at two rock-shelters under the Highland Archaeological project (Shoocongdej, 2006) and burials reported by Pureepatpong (2006). At Tham Lod remains of four individuals were found, although only two were in situ, one dated to 13640 ± 80 BP, and a second to 12100 ± 60 BP (Pureepatpong, 2006: 38). At Ban Rai one individual was dated to 9720 ± 50 BP (Pureepatpong, 2006: 39).

Also from northern Thailand but in the basin of the Chao Phraya River, is a single burial from the site of Ban Tha Si. This was again poorly preserved and only partly represented, and was dated to a minimum age of c. 7000 BP (Zeitoun et al., 2013).

Further afield in Western Thailand, but also in the basin of the Chao Phraya, is a single individual at Sai Yok, Kanchanaburi province, dated to between 8000 and 10000 BP, and 4000 BP (Jacob, 1969: 49).

Other pre-metal age skeletons have been found in the peninsula forming southern Thailand (Moh Kiew: Pookajorn, 1994; Auetrakulvit et al., 2012), and Malaysia (the complete skeleton from Perak, and a number of others: Majid, 2005) but here we have geographically constrained the comparative samples to further north in mainland Southeast Asia, closer to Pha Phen. Most significantly, this brief review has shown that Pha Phen represents an important contribution to understanding of human biology during the period around 6000 BP in the watershed of the Mekong River basin/valley.

Aside from the issues of chronological relativity, clearly our ability to compare the individual represented by the Pha Phen burial with others from the region is limited both by the data we were able to acquire with the skeleton in situ, and by the published information on comparative samples. We have made no attempt to compare the Pha Phen craniofacial skeleton metrically or morphologically with the comparative samples, as inaccessibility of the vault and damage to the anterior cranium and face made it impossible to take any craniofacial metrics. The extreme wear on the teeth precluded dental measurements and assessment of morphology. Three features of the Pha Phen burial that we are able to consider in placing Pha Phen in context are environmental and cultural, i.e. burial position and dental health; and genetic but strongly influenced by environment, i.e. stature.

Considering first burial position (Table 1), the Pha Phen skeleton (Figure 2) was lying on one side with the upper limbs partly flexed at the elbow joints so the forearms are lying across the abdomen. The lower limbs are partly flexed at the hip joints and fully flexed at the knee joints. Information available on burial position of the comparative samples is variable in quantity and quality. Fromaget and Saurin describe the finding of six individuals at Tam Hang Sud/South, four adults (two males, two females) and two children (Fromaget and Saurin, 1936: 14; 41). Three of the adults were buried supine but there is no indication of the position of the fourth, or information on sexes of the supine burials. At Tam Hang Nord/North they found one adult skeleton, extended and lying on the left side, and two children squatting against the wall of the rock shelter. They hypothesize that these three were victims of a landslide (Fromaget and Saurin, 1936: 15) and so their positions are not indicative of burial custom. They report the single skeleton at Tam Pong (Fromaget and Saurin, 1936: 14) as squatting or crouched, “lying on the back,” without further detail. Fromaget and Saurin estimated age at death as young adult and sex as female (Fromaget and Saurin, 1936: 37). Olivier (1966: 236) agreed with the age estimation but disagreed with the sex on the basis of skull size and morphology, acknowledging that young males in Southeast Asia frequently have not developed the full suite of masculine cranial characteristics.

Most of the historically excavated Vietnamese samples have no description of burial position. Although Mansuy (1925a: 34) discusses whether or not the skeletons from Pho-Binh-Gia and Dong Thuoc in particular were deliberate burials, again she gives no details of burial position. The more recently excavated Hang Cho individual (age at death estimated as “old,” sex estimated as female) had the upper body supine (Matsumura et al., 2008: 205). The long bones of the lower limbs had been lost in prehistory but the position of the feet, adjacent to the pelvis, shows that the lower limbs would have been partly flexed at the hip joints and tightly flexed at the knee joints, so the thighs and lower legs were almost vertical. The knees would have been significantly elevated relative to the rest of the skeleton, with this position allowing the feet to be flat on the ground. The Mai Da Nuoc individual (age estimated as > 40, sex estimated as male) is described as having been buried supine (Nguyen, 1986), although it is unclear how much of the postcranial skeleton was present. It is possible that, if only upper-body appendicular bones had survived, the interment had been in a similar position to that at Hang Cho. At Con Co Ngua, Oxenham (2000: 11), citing an unpublished report by Bui Vinh (1980), describes the burial positions: “In the majority of cases, individuals were buried tightly flexed, both the upper and lower limbs, in a type of squatting or seated foetal position.” It also appears that human skeletal remains at some sites may have represented secondary burials, particularly at Lang Gao, where the skulls appear to have been deliberately placed.

The position of Pha Phen is similar to that found in the Salween River catchment sample with the later of two in situ burials at Tham Lod (Shoocongdej, 2006: 31; Pureepatpong, 2006: 39), although the earlier burial is described as extended (Pureepatpong, 2006: 38). The nearby Ban Rai burial has the upper body supine but the lower limb joints appear to have been very tightly flexed so the knees were pulled against the chest (Pureepatpong, 2006: 39). The > 7000 BP burial from Ban Tha Si in the Chao Phraya River catchment is described as lying on its side, with flexed limbs and the hands close to where the chin would have been (the skull is not present) (Zeitoun et al., 2013: 130). The drawing of the skeleton shows that the lower limbs were tightly flexed at the hip and knee joints, with the knees again pulled towards the chest.

The Sai Yok individual was also buried with the upper body supine and the knees elevated and tightly flexed (Jacob, 1969: 49), in the same position as the Hang Cho individual.

The position of the Pha Phen burial was similar to that seen in one burial at Tham Lod, and the one at Ban Tha Si, although the upper limbs were more tightly flexed at the elbow joints in the latter case. The Con Co Ngua burials have the body arranged in a similar way but with the trunk placed upright rather than lying on the side. The Ban Rai, Sai Yok, and Hang Cho burials were placed with the upper body supine and the lower limbs flexed, either partly or fully, at the hip joints and fully flexed at the knee joints so the knees were either elevated above the plane of the body or drawn against the chest.

The exceptions among the burials that are described are the supine, extended, burials from Tam Hang, Tham Lod, and Mai Da Nuoc, dating several millennia earlier than Pha Phen. Zeitoun et al. (2013) have reviewed the burial position of approximately contemporary burials within Thailand and record that burials from Moh Khiew (burials dating c. 26000–8000 BP, with the majority 11000–9000 BP: Zeitoun et al., 2013: 134), in southern Thailand, included both flexed and supine at different levels of the site.

It is clear that there is no one position adopted for the few interments found in the river valleys in the wider region around the middle Mekong River that date from the period 13000–4500 BP, although a majority have some degree of flexion of the limbs. Nor is there any clear relationship between position and sex or age at death, although this interpretation carries with it the caveat that estimation of age and sex is subject to considerable variation among researchers, and certainly over the time period represented by the research projects under which the remains were recovered, from the early 20th century to the very recent. It is also clear from the range of burial positions described that there could be a variety of interpretations of the meaning of ‘flexed’ burials. Ideally, descriptions of burials would include full details of the positions of the components of the body, using anatomical terms for the position of the limbs.

The dental health of Pha Phen is dominated by extreme wear, particularly of the anterior teeth. There is no pulp exposure, no visible caries, or antemortem tooth loss but infection or inflammation of one tooth.

The availability of dental health evidence is highly variable (Table 2) and ranges from minimal evidence of one oral condition in one individual (e.g. Khac Kiem: Mansuy, 1925b; Sao Dong: Colani, 1927b) to detailed evidence in many individuals (Con Co Ngua: Oxenham, 2000; Oxenham et al., 2006); the data available suggest that all samples have heavy wear, although the rate at which it progressed may have been slower at Pha Phen than Sai Yok or Hang Cho where pulp cavities are exposed. This, of course, has the caveats that not all teeth are visible at Pha Phen and the unusual wear angle on some anterior teeth may be indicative of use of teeth for other than mastication. The presence of infection/inflammation and antemortem loss of teeth appear to be a consequence of the heavy wear in almost all cases, as there are no recorded caries with the exception of the possible cervico-enamel junction caries mentioned by Mansuy and Colani (1925) in relation to skull 10 from Lang Cuom. Despite the coastal location of Con Co Ngua, with the possibly different diet compared with the rest of the samples, the patterns of oral health at this site are not inconsistent with the remaining samples.

| Site | Dental conditions |

|---|---|

| Pha Phen | Severe wear, no caries, antemortem loss: one periapical infection/inflammation |

| Tam Hang | Antemortem loss: ablation |

| Khac Kiem1 | Mandible edentulous, alveolar process resorbed |

| Dong Thuoc | “Irregular, crowded, oblique wear” (Mansuy, 1924: 18) Molar wear extreme, pulp cavity exposure (Mansuy, 1924: plate XIII) |

| Lang Cuom | Severe wear, possible cervico-enamel junction caries (Mansuy and Colani, 1925: 18) |

| Sao Dong | Severe wear (Colani, 1927b: Plate III) |

| Som Jo | Minimal wear (probably young adult) (Colani, 1927b: plate X) |

| Mai Da Nuoc | No antemortem loss |

| Hang Cho | Very severe wear, antemortem loss, infection/inflammation, no caries (Matsumura et al., 2008: 207) |

| Tham Lod, Burial 2 | Periodontal disease (Pureepatpong, 2006: 41) |

| Ban Rai | Severe wear, antemortem loss, no caries (Pureepatpong, 2006: 41) |

| Sai Yok | Heavy wear, no antemortem loss (Jacob, 1969: 45, plate XXIII) |

| Con Co Ngua | Heavy wear; minimal caries, infection, inflammation, and antemortem loss |

References as for Table 1.

As body proportions are sexually dimorphic, comparison of the stature of Pha Phen is limited to those with sex estimated to be male. Ideally stature should be calculated using the same stature estimation equations and the same long bone. In this case the femur was used, as this is the only bone available for Pha Phen. This limits comparison (Table 3) to Ban Rai (Pureepatpong, 2006), Ban Tha Si (Zeitoun et al. (2013), a single male from Tam Hang (Shackelford and Demeter, 2012), and five males from Con Co Ngua (Oxenham, 2000). Femoral lengths and stature estimates, both from the above publications and recalculated using the Pureepatpong et al. (2012) equations, which are based on a large sample of modern Thai cadavers (n = 228), are detailed in Table 3. A single femur from Lang Cuom, without a sex estimate, was measured at 385 mm (Mansuy and Colani, 1925: 10), which would indicate a very short individual so may belong to a female.

| Femur length (mm) | Stature (cm) | Staturee | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pha Phen | 478 | 175.56 ± 4.06a | Femur | 174.4 |

| Tam Hang | 436 | 162.5b | Femur or tibia | 165.8 |

| Ban Rai | 395 | 156.42 ± 5.3885c | Femur | 154.6 |

| Con Co Ngua | 431–480 | 162.65–176.57d | Femur | 163.2–174.9 |

References as for Table 1.

It is clear that the Pha Phen femur is at the upper end of the range of these comparative samples. Only Ban Tha Si and the tallest individual from Con Co Ngua are longer, and then only by 1–2 mm. The estimation of stature from long bone lengths is complicated by differences in body proportions among populations. Comparing the estimations using Pureepatpong et al.’s (2012) equation with those calculated using equations from other sources, all except the Tam Hang calculation produced results with less than 2 cm difference. The Tam Hang calculation used equations calculated from a Japanese sample, which may be less applicable than the Thai equations of Sangvichien et al. (1985) and Pureepatpong et al. (2012). This example is further complicated in that Shackelford and Demeter do not state whether the calculation for this individual was based on femoral or tibial lengths, both of which were available to them. Accepting that the Pureepatpong calculations are most appropriate, Pha Phen is almost 10 cm taller than Tam Hang, 20 cm taller than Ban Rai, and as tall as Ban Thai Si and the tallest from Con Co Ngua. We can safely conclude that he was tall for this period of prehistory. We do not have data for joint dimensions from the comparative samples but, as argued earlier, compared with more recent prehistoric Southeast Asians, he was slender.

This paper reports on an isolated skeleton of a tall, slender adult male, estimated to be of middle adult age but with extreme dental wear that may reflect industrial use of the teeth. The bones are coated with a light concretion and the skeleton remains in its original position, as it is to be exhibited at the Laos National Museum in Vientiane, limiting the amount of information that can be acquired. The skeleton was originally assessed as Neolithic on the basis of the burial position and a radiocarbon date of c. 7000 BP, with confirmation of a more precise attribution to era subject to replication of the date.

This individual is the only skeleton described from that period in the region of the Mekong River watershed that is now central Laos. To place the burial in context, aspects such as burial position, dental health, and body size are compared with approximately contemporary pre-metal age burials dating from c. 16000 to 5000 BP in the wider region of mainland Southeast Asia. The information available from these burials varies from very little in the case of those researched historically, to more detail in those more recently researched, although since the focus of many publications was on biological distance through the medium of cranial and dental morphology, the specific information needed to draw comparisons with Pha Phen is variably provided.

The burial positions of Pha Phen and the comparative burials are highly variable, suggesting that there was no universal custom. This could be seen as not entirely surprising, given the c. 10000 years and wide geographic region covered by the sample available. The range from tightly contracted skeletons, with both the axial skeleton and lower limbs fully flexed, to fully extended, supine burials is represented, along with a range of variations on these extremes. There appears to be no pattern based on dating or location of the burial or age at death or sex of the individual being buried, although the quality of the data available for all these factors, with the exception of geographic location, is variable depending on when, and for what purpose, the burials were excavated and published.

The oral conditions of the people represented by the sample are also highly variable, with no apparent relationship to estimates of age at death or sex, where these are available. Both age and sex, in addition to diet, have a significant influence on dental health, but, as already noted, the methods of estimation of both parameters have changed significantly over the many decades represented by the estimates available for the samples discussed here. There is also no discernible pattern in the type and severity of oral/dental pathology identified but the general impression is one of very low caries rates, severe occlusal wear that occurred at different rates but in some cases pulp cavities were exposed, suggesting rapid wear and an associated potential for infection; in other cases, as with Pha Phen, the formation of secondary dentine prevented exposure of the cavity and reduced infection potential. Antemortem loss was common, probably consequent on the wear, and infections were identified in some cases.

There was no systematic recording of periodontal health, and only one case of probable ablation of anterior teeth. The measurements available for the long bones of Pha Phen suggest he was very tall for this period of prehistory, but probably slender, compared with his contemporaries.

We thank the Ministry of Information, Culture and Tourism of the Lao People’s Democratic Republic for the opportunity to undertake this project, and the Laos National Museum for its hospitality during the research. Marion Ravenscroft, Conservator at the Museum, provided invaluable assistance, as did staff of the Ministry, especially Pimmaseng Khamdalavong. We thank Robbie McPhee for the drawing of Figures 1 and 2 and Nigel Chang for Figure 4. Travel and accommodation for Tayles and Halcrow was funded by the University of Otago.