2016 Volume 80 Issue 5 Pages 1148-1152

2016 Volume 80 Issue 5 Pages 1148-1152

Background: The long-term outcomes of mitral valve (MV) repair for active infective endocarditis (AE) are not well known, so the present study examined results from >5 years.

Methods and Results: We retrospectively reviewed 43 patients who underwent primary MV repair for AE at a single center between 1991 and 2009. Patients’ mean age was 50.9 years, and 39% were female. The mean follow-up was 7.4 years, and 90.7% of the patients had serial echocardiographic studies over the years. We examined the data for mortality, mitral reoperation, and recurrent significant mitral regurgitation (MR). There were no early deaths but 6 late deaths. Survival was 92.6±4.1% for 5 years, and 83.5±7.3% for 10 years. The respective 5- and 10-year rates of freedom from MV reoperation were 90.5±4.5% and 86.6±5.8%, and for freedom from moderate or severe MR were 95.0±3.5 and 86.1±6.7%. Recurrence of endocarditis was observed in 2 patients (4.7%). Most (86%) of the survivors were in New York Heart Association class I.

Conclusions: MV repair for AE is durable and offers acceptable long-term outcomes with low rates of recurrence and reoperation. (Circ J 2016; 80: 1148–1152)

Mitral valve (MV) repair, when feasible, is superior to MV replacement. Benefits include preservation of cardiac function, improved quality of life, greater freedom from reoperation, lower operative mortality, and favorable long-term survival.1–3 Dreyfus et al4 reported on the first series of MV repair performed during the acute phase of endocarditis. Since that report, the feasibility of MV repair in acute infective endocarditis (AE) has varied as reported by several researchers.5–10 However, existing studies include relatively few patients and/or limited follow-up (mainly <5 years) with a few exceptions.8,9

This study examines our clinical experience with MV repair for AE over more than 5 years.

The Institutional Review Board of Kobe City Medical Center General Hospital approved this retrospective study of 43 patients (female, n=19; male, n=24; mean age 50.9±19.7 years, range 18–84) who underwent MV repair for active native MV endocarditis between November 1991 and June 2009. None were intravenous drug abusers.

Endocarditis was defined based on the Duke criteria.11 Endocarditis was considered active when the operation was performed during the first 6 weeks of antibiotic therapy.4 The New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional classes before surgery were III and IV in 15 (35%) and 13 (30%), respectively. The preoperative cardiac rhythm was atrial fibrillation in 1 patient (2%) and sinus rhythm in the remainder. On preoperative transthoracic echocardiography, mitral regurgitation (MR) severity was graded as moderate in 3 patients (7%) and severe in 40 patients (93%). Mean left ventricular ejection fraction measured by echocardiography was 63.6±9.5%.

Operation was indicated before the initial full course of antibiotics was completed for the following main reasons: heart failure in 6 patients (14%); large vegetations and/or systemic emboli in 32 patients (74%); persistent sepsis in 5 patients (12%).

BacteriologyThe microorganisms responsible for endocarditis are shown in Table 1. The most common infecting organisms were streptococcal species in 21 patients (49%) and staphylococcal species in 9 (21%). Organisms were isolated from blood culture in 24 patients (56%).

| Gram-positive cocci (n=33) |

| Streptococcaceae, 21 |

| Oral streptococci, 6 |

| α hemolytic-streptococcus, 9 |

| β hemolytic-streptococcus, 2 |

| Streptococcus agalactiae, 1 |

| Streptococcus constellatus, 1 |

| Enterococcus faecalis, 2 |

| Staphylococcaceae, 9 |

| MSSA, 6 |

| MRSA, 1 |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis, 1 |

| Staphylococcus horminis, 1 |

| Aerococcus uriae, 1 |

| Culture unknown, 1 |

| Gram-negative bacilli (n=3) |

| Klebsiella pneumonia, 1 |

| Pseudomonas stutzeri, 1 |

| Culture unknown, 1 |

| Fungi (n=1) |

| Candida parapsilosis, 1 |

| Unknown (n=6) |

All procedures were performed through a median sternotomy and involved cardiopulmonary bypass with bicaval cannulation and systemic mild hypothermia. Myocardial protection was identical for all patients and consisted of antegrade cold blood cardioplegia. The MV was exposed through a right-sided left atriotomy.

Pathologic findings consisted of vegetations (84%), valve prolapse caused by chordal rupture (35%), leaflet perforation (33%), and annular abscess (7%). Infection also involved the aortic valve in 13 patients (30%) and the tricuspid valve in 2 patients (5%) (Table 2).

| Lesion | n |

|---|---|

| Chordal rupture | |

| Anterior leaflet | 12 |

| Posterior leaflet | 7 |

| Perforation | |

| Anterior leaflet | 11 |

| Posterior leaflet | 2 |

| Vegetation | |

| Anterior leaflet | 20 |

| Posterior leaflet | 27 |

| Annular abscess | 3 |

After assessing the whole mitral apparatus, all macroscopically involved tissue was widely removed without any concern about the possibility of repair. Valve reconstruction was then performed, which included leaflet resection (84%), pericardial patch (72%), direct suturing of perforation (37%), and chordal reconstruction with artificial chordae (15%). Prosthetic annuloplasty were performed in 24 cases (58%) of annular dilatation. Repaired MV competence was routinely assessed using intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography and the maximum area of residual MR was evaluated after weaning from cardiopulmonary bypass. In the case of a maximal area regurgitant jet >2 cm2 or a regurgitant jet impinging on the ring, a second pump run was made to re-repair; 8 patients (19%) required a second pump run followed by successful re-repair.

Associated procedures were performed in 23 patients. The aortic valve was repaired (3 patients) or replaced (5 bioprosthesis, 4 stentless bioprosthesis, 4 mechanical valves, and 1 Bentall operation). Repair of the tricuspid valve was also performed in 5 patients. Table 3 shows the surgical procedures.

| n | |

|---|---|

| Repair technique | |

| Leaflet resection-suture | 36 |

| Pericardial patch | 31 |

| Direct suture of perforation | 16 |

| Chordal reconstruction | 15 |

| Annuloplasty | |

| Prosthetic ring | |

| Duran ring | 6 |

| Duran band (partial ring) | 14 |

| Physio II | 2 |

| Pericardial strip | 7 |

| Concomitant procedures | |

| Aortic valve replacement or repair | 18 |

| Tricuspid valve repair | 5 |

| 2nd pump run | 8 |

The completeness of follow-up was 95% and the mean duration was 7.4±4.6 years (maximum 20.6 years). Follow-up data were obtained from reviews of outpatient charts or by telephone or mail. Follow-up echocardiography was preceded by an interval of 1–2 years, but then more frequently if indicated. The completeness of follow-up echocardiography was 90.7%. The mean time to the last echocardiogram was 6.3±4.6 years (maximum 18.3). The grade of MR was classified as none/trace, mild (1+), moderate (2+), or severe (3+) according to the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association 2006 guidelines.3

The primary endpoint of the study was death. Postoperative mortality and morbidity were analyzed according to the joint Society of Thoracic Surgeons, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, and European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery Guidelines.12 Long-term results were also assessed on the basis of NYHA functional class and echocardiography.

Statistical AnalysisData are presented as mean±standard deviation for continuous variables and as simple ratio (%) for categorical variables. Estimates of survival and freedom from valve-related events were calculated by Kaplan-Meier method and expressed as the ratio (%)±SE of patients who remained event-free. Cox regression analysis with backwards selection was used to identify independent predictors of late outcomes by entering all variables with a univariate probability value less than 0.2 but failing to meet the statistical significance level. Variables submitted to the models included: age at the time of the operation, sex, diabetes, hypertension, cerebrovascular disease, NYHA functional class, leaflet prolapsed, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) induced, and concomitant surgery. Statistical analysis was performed with JMP® software for Windows, 12.1.0 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC, USA).

During the 19-year study, 47 patients were admitted with AE of the native MV and of them, 4 (8.5%) underwent MV replacement. Thus, MV repair was possible in 91.5% in this study.

Perioperative Morbidity and Hospital MortalityThere were no hospital deaths among the 43 patients. Postoperative morbidity included cerebral infarction (2 patients, 5%), cerebellar bleeding (1 patient, 2%), low cardiac output syndrome (1 patient, 2%), complete AV block requiring pacemaker implant (1 patient, 2%), respiratory failure (1 patient, 2%), renal failure necessitating temporary hemodialysis (1 patient, 2%), and mediastinitis (1 patient, 2%). Median intensive care unit stay was 3 days (range 1–40 days). One patient underwent reoperation on postoperative day 3 after the operation, which consisted of a glutaraldehyde-treated pericardial patch closure for perforated anterior leaflet and partial ring annuloplasty. Severe MR associated with an increase in pulmonary artery pressure, secondary to the patch perforation and anterior leaflet chordal rupture, occurred postoperatively and required emergency surgery. The MV was re-repaired, consisting of closure of the perforation and chordal transfer.

Long-Term EvaluationFollow-up was complete in 41 patients (95%). Mean follow-up was 7.4±4.6 years (range 0.07–20.6 years).

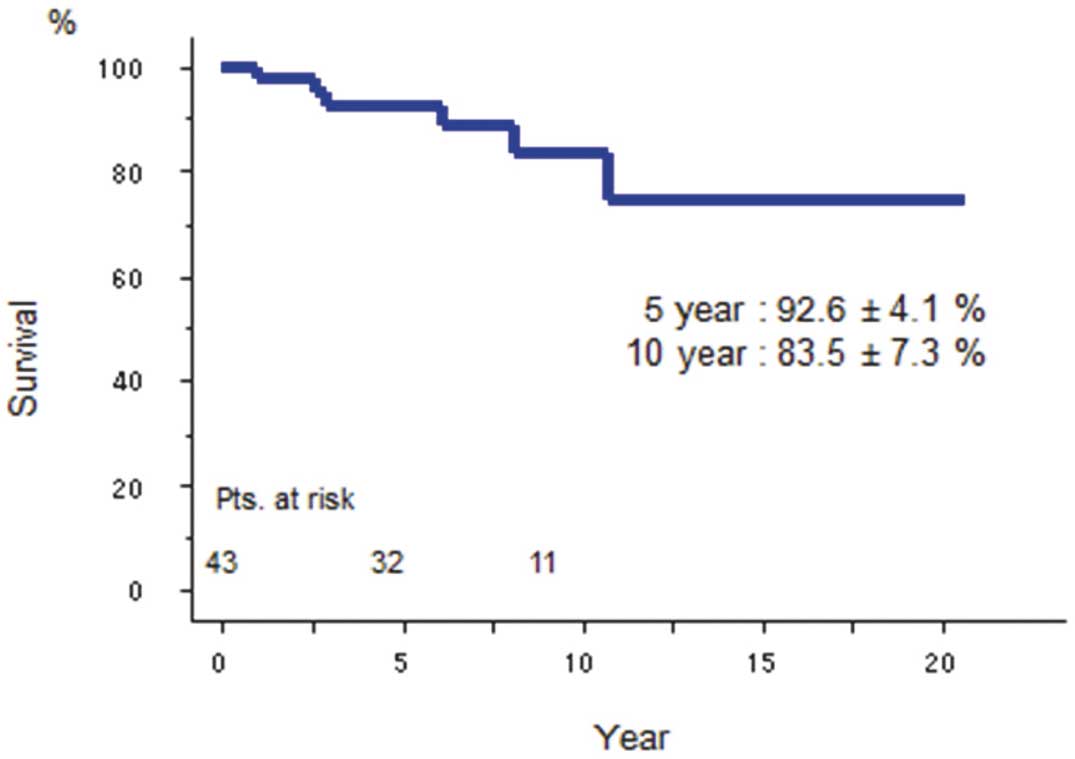

Long-Term SurvivalLate deaths of 6 of the 43 patients occurred (11%); 2 died of noncardiac causes (carcinoma, n=1, pneumonia, n=1), 2 died of cardiac causes (arrhythmia, n=1, cardiogenic shock, n=1), and 2 died of unknown causes. The 5- and 10-year actuarial survival rates including hospital deaths were 92.6±4.1% and 83.5±7.3%, respectively (Figure 1). The mean NYHA functional class of the survivors was 1.2±0.4. The Cox regression hazard model could not identify any variables as risk factors for late death.

Actuarial survival of patients undergoing mitral valve repair duirng active infective endocarditis.

Endocarditis In 2 patients there was recurrence of endocarditis; 1 patient underwent MV repair during the acute phase of Candida parapsilosis endocarditis and 4 months later there was recurrence of the infection. The patient underwent repeat repair of the MV, but 1 year later, he had MR with hemolysis, and underwent MV replacement with a bioprosthesis. The other patient had MV repair during the acute phase of MRSA endocarditis, but infection recurred 5 months later and she underwent MV replacement with a bioprosthesis.

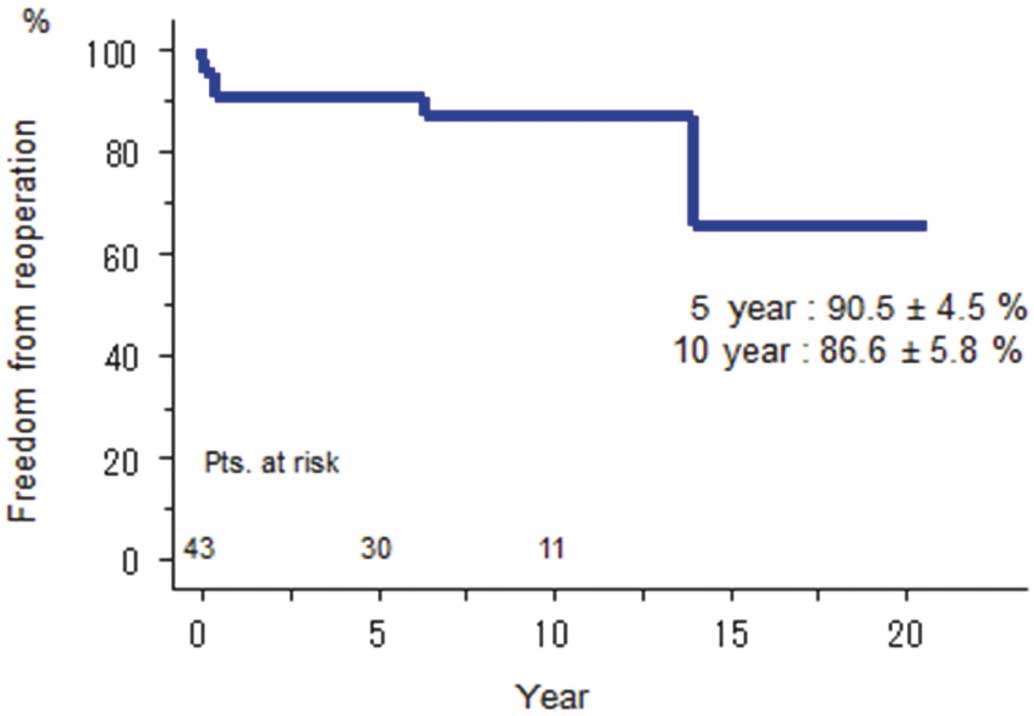

Reoperation Reoperation of the MV was performed in 4 patients. Indications for MV redo surgery were endocarditis (n=2, as mentioned before), MR with hemolysis in 1 patient, and severe MR in 1 patient. The case of MR accompanied by hemolysis occurred as a result of artificial chordae rupture. In the other case, MR deteriorated likely because of annular dilatation. These 2 patients underwent mechanical MV replacement 1 month after the first surgery and bioprosthetic MV replacement 14 years after the first surgery.

The 5- and 10-year actuarial rates of freedom from reoperation were 90.5±4.5% and 86.6±5.8%, respectively in all patients (Figure 2). There were no independent predictors of reoperation.

Freedom from reoperation among patients undergoing mitral valve repair duirng active infective endocarditis.

Thromboembolism and Bleeding Events All patients with atrial fibrillation received permanent anticoagulation therapy with warfarin after surgery. Patients with sinus rhythm received anticoagulation for the first 3 months after surgery. A thromboembolic event occurred in 1 patient, who had minor embolic episodes without permanent neurologic deficit. A bleeding event occurred in 1 patient, who had cerebral bleeding without permanent neurologic deficit 4.5 years after surgery. That patient had warfarin for concomitant aortic valve replacement with mechanical valve.

Recurrence of Significant MR There was recurrence of significant MR ≥2+ during the follow-up period in 6 patients and of them, 3 required reoperation.

The 5- and 10-year rates of freedom from significant MR evaluated by serial echocardiography were 95.0±3.5% and 86.1±6.7%, respectively for all patients (Figure 3). Univariate Cox identified male sex ((P=0.037, hazard ratio: 1,116,068,197.9528; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.1628–1.1628) and cerebrovascular disease (P=0.0174, hazard ratio: 9.608; 95% CI: 1.531–76.145) as independent predictors of recurrent significant MR. On multivariate analysis, we could not identify any variables as risk factors for recurrent significant MR.

Freedom from recurrent mitral regurgitation patients undergoing mitral valve repair duirng active infective endocarditis.

We have shown that MV repair for AE was performed with a low operative mortality (0%) and good long-term results in the present study. After the operation, 86% of the survivors were in good functional status, NYHA class I. Recurrence of endocarditis was low (5%), and the 10-year freedom from mitral reoperation was high (86.6%). The 10-year freedom from significant MR was also high (86.1%).

Dreyfus et al reported on the first series of MV repair systematically performed during the acute phase of endocarditis.4 The feasibility of MV repair in AE was vary as reported by several researchers. Gammie et al reported the feasibilities of MV repair were 40.9% for treated endocarditis and 15.9% for AE in North America.13 Ferringa et al reported the feasibility as 39% from a review of literature.14 We tried to increase the feasibility of MV repair using autologous pericardium as the repair material. Autologous pericardium patching was used in 31 patients (72%) and pericardium strip as a partial ring was used in 7 patients (16%). The autologous pericardium was fixed in a 0.6% glutaraldehyde solution for 15 min and rinsed in saline for 15 min.15 In our series, the feasibility of MV repair was 82.7%. Zegdi et al8 and de Kerchove et al9 have reported good feasibility rates of MV repair for AE of 75% and 80%, respectively, using autologous pericardium.

The optimal timing of surgery has been a controversial issue in the management of infective endocarditis. Some reports advocate early operation for patients suffering from endocarditis.4,16 Early MV repair may limit infection to the leaflets, thus preventing leaflet destruction, which makes valve repair more difficult. However, cerebral complications before operation make the surgeon’s decision difficult regarding the timing of valve surgery. The guidelines from the American Heart Association17 and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons18 recommend delaying surgery in endocarditis patients by at least 4 weeks from onset of cerebral complications. However, several studies reported that patients with preoperative cerebral infarction have a relatively low risk of postoperative neurologic deterioration caused by secondary cerebral hemorrhage related to cardiac surgery.19,20 In the present study, we had 20 (47%) patients who had cerebral infarction likely because of embolization of endocardial vegetation. Early surgery may also prevent vegetation embolization and preserve LV function.

Recurrence of endocarditis is a serious complication after valve replacement in AE, although the rate of recurrence has been reported as less than 10%.21,22 Several studies have shown no or less frequent recurrence of endocarditis in their early- or mid-term follow-up after MV repair.4–7 Although statistically insignificant, Ruttman et al demonstrated that freedom from recurrence of endocarditis at 5 years was better for those who underwent MV repair for AE compared with those who had MV replacement (96.4% vs. 82.7%, P=0.086).23 In the present study, we observed recurrence of endocarditis in 2 patients. One patient was a 55-year-old man who had initial MV repair for AE caused by Candida parapsilosis and then underwent MV repair at 5 months after the first operation because of recurrence. He later underwent had MV replacement 14 months after the redo surgery, because of hemolysis. The other patient was a 28-yearold woman who had initial MV repair for MRSA endocarditis and then underwent MV replacement with a bioprosthesis 5 months after the first surgery because of recurrence.

The use of prosthetic material in AE is still controversial. However, there has not been a study showing evidence that the use of a prosthetic annuloplasty ring is responsible for a higher recurrence rate of endocarditis. We used prosthetic rings in 58% of our patients, even though this annuloplasty might have a risk for recurrent bacterial colonization. We did not hesitate to use a prosthetic ring in patients with annular dilatation from the viewpoint that residual MR also carries a high risk for recurrence. However, we believe radical debridement of all infected tissue is a precondition.

The 5- and 10-year survival rates were 92.6% and 83.5%, respectively, in the present study. These results compared favorably with the previous report by Zegdi et al that the 5- and 10-year survival were 89% and 80%, respectively.8 Ruttman and associates reported that their 5-year survival was 85.1% in the MV repair group and 66.6% in the MV replacement group for AE.23 In the present study there were 4 reoperations (2 endocarditis, 1 MR, 1 hemolysis). Freedom from mitral reoperation was 90.5% and 86.6% at 5 and 10 years, respectively, which compares favorably with the 85.5% at 5 years for MV replacement in AE reported by Ruttman et al.23 Zegdi et al also had a positive outcome regarding freedom from reoperation.8

Freedom from MR that was equal to or more than moderate was 95% and 86.1% at 5 and 10 years, respectively, in the present study. The 10-year MR-free rate in the present study was also as good as the long-term results reported for MV repair for degenerative disease.24 Male sex and cerebrovascular disease were independent predictors of recurrent significant MR in the present study. However, we could not ascertain the reason why. We could show MV repair for AE is also durable. In the present study, we used glutaraldehyde-treated autologous pericardium as a pericardial patch in 31 (72%) patients. Kerchove and colleagues reported the durability of MV repair for AE using patch techniques as similar to that of repair without patch techniques.9 Shomura and colleagues reported MV repair with glutaraldehyde-treated autologous pericardium and 5-year rates of freedom from reoperation of 94±3% decreasing to 10 years of 82±7% in their series.25 Although using autologous pericardium in MV repair can avoid the use of prosthetic valves in patients with AE, there is a case report of a patient with a history of mitral and aortic valve repair with glutaraldehyde-treated autologous pericardium undergoing double valve replacement for mitral stenosis that developed because of severe calcification of the autologous pericardium.26 Therefore, close follow-up is mandatory.

Study LimitationsMost limitations were associated with the retrospective nature of the review of clinical outcomes of MV repair for AE at a single institution. From the standpoint of patients’ profiles and overall relatively small sample size, the results may not be generalizable compared with another high-volume center.

There also exists the possibility that we underestimated the incidence of recurrent MR, because the echocardiography follow-up rate was less than the survival follow-up rate. In this study, we did not compare the results of MV repair and MV replacement. Around the same time, we mainly performed MV repair for AE and MV replacement for 4 patients. Therefore, we thought it was not reasonable to compare the results of MV repair with those of MV replacement. We tried to analyze and find the factors associated with long-term clinical outcomes such as survival, reoperation, and recurrent significant MR. But it is doubtful whether it is appropriate to try to identify them in light of the small sample size. No drug abusers were included in this series because drug abuse is more strictly prohibited than in Western countries. Other studies included 3–8% of drug abusers in their series.4,22,27

In conclusion, MV repair for AE is a safe and durable for more than 5 years.

None.