2015 Volume 235 Issue 3 Pages 215-222

2015 Volume 235 Issue 3 Pages 215-222

Devastating natural disasters and their aftermath are known to cause psychological distress. However, little information is available regarding suicide rates following tsunami disasters that destroy regional social services and networks. The aim of the present study was to determine whether the tsunami disaster following the Great East Japan Earthquake in March 2011 has influenced suicide rates. The study period was from March 2009 to February 2014. Tsunami disaster-stricken areas were defined as the 16 municipalities facing the Pacific Ocean in Miyagi Prefecture. Inland areas were defined as other municipalities in Miyagi that were damaged by the earthquake. Suicide rates in the tsunami disaster-stricken areas were compared to national averages, using a time-series analysis and the Poisson distribution test. In tsunami disaster-stricken areas, male suicide rates were significantly lower than the national average during the initial post-disaster period and began to increase after two years. Likewise, male suicide rates in the inland areas decreased for seven months, and then increased to exceed the national average. In contrast, female post-disaster suicide rates did not change in both areas compared to the national average. Importantly, the male suicide rates in the inland areas started to increase earlier compared to the tsunami-stricken areas, which may reflect the relative deficiency of mental healthcare services in the inland areas. Considering the present status that many survivors from the tsunami disaster still live in temporary housing and face various challenges to rebuild their lives, we should continue intensive, long-term mental healthcare services in the tsunami-stricken areas.

Tsunami can cause enormous damage, including thousands of casualties and destruction of entire towns in an instant. Tsunami can decimate not only regional infrastructure and buildings, but also social services and networks. The Great East Japan Earthquake, which occurred on March 11, 2011, was the largest earthquake in Japanese history (Ishigaki et al. 2013). The earthquake generated a massive tsunami with a maximum height of 9.3 m, which traveled up to 10 km inland in flat areas. According to Japanese Fire and Disaster Management Agency, this disaster led to 18,958 deaths and 2,655 missing people, with more than 90% of the deaths due to drowning. In addition, the earthquake caused an accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, which forced many residents in surrounding areas to evacuate (Ishigaki et al. 2013).

Devastating natural disasters and their aftermath are known to cause psychological distress in affected individuals (Murphy 1986; Kiliç and Ulusoy 2003). There has been an increasing amount of studies concerning post-disaster mental distress, including posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, and suicidality (Wu et al. 2006; Hyodo et al. 2010; Suzuki et al. 2011). These studies suggest that prompt mental healthcare is required following a disaster. In the case of the Great East Japan Earthquake, mental health care activities were provided in both tsunami disaster-stricken areas and inland areas early on in the post-disaster period, including psychological first aid, screening for people who needed observation or support, health screening, public information, counseling services, and support from outside volunteers (Kim 2011; Takeda 2011; Suzuki and Kim 2012; Matsuoka 2012). These mental health care services have been offered on an ongoing basis. According to the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare (http://www.mhlw.go.jp/jishin/joukyoutaiou.html), as of February 24, 2012, a total of 3,498 mental health professionals have provided mental health care within disaster-stricken areas. The mental health care activities were described in detail by Kim (2011). However, according to reports from the Miyagi Prefectural Government or Sendai City office, eventually, the outside volunteer support came to an end, with available services shifting back to the usual mental health and medical care system, particularly in inland areas. Meanwhile, many evacuees remain in the tsunami disaster-stricken areas with severe damage, and are forced to live in temporary housing; thus, provision of mental health services for these individuals has continued to date.

A previous study investigating the association between tsunami disasters and suicide rates reported no significant changes in suicide rates in affected areas of Sri Lanka (Rodrigo et al. 2009). However, it is difficult to estimate changes in suicide rates following the Great East Japan Earthquake because of the limited evidence available regarding tsunami disasters and suicide behaviors (Kõlves et al. 2013). The purpose of this study was to observe changes in suicide rates in tsunami disaster-stricken areas in Miyagi Prefecture, which was home to the majority of victims of the tsunami disaster following the Great East Japan Earthquake. According to the Japanese Fire and Disaster Management Agency (http://www.fdma.go.jp/bn/higaihou/pdf/jishin/149.pdf), the death toll and numbers of missing individuals in coastal municipalities were as follows: Iwate 6,218, Miyagi 11,707 and Fukushima 3,270 (as of March 7, 2014). We also hope to utilize the present study findings to determine future policies regarding mental care activities in Miyagi Prefecture.

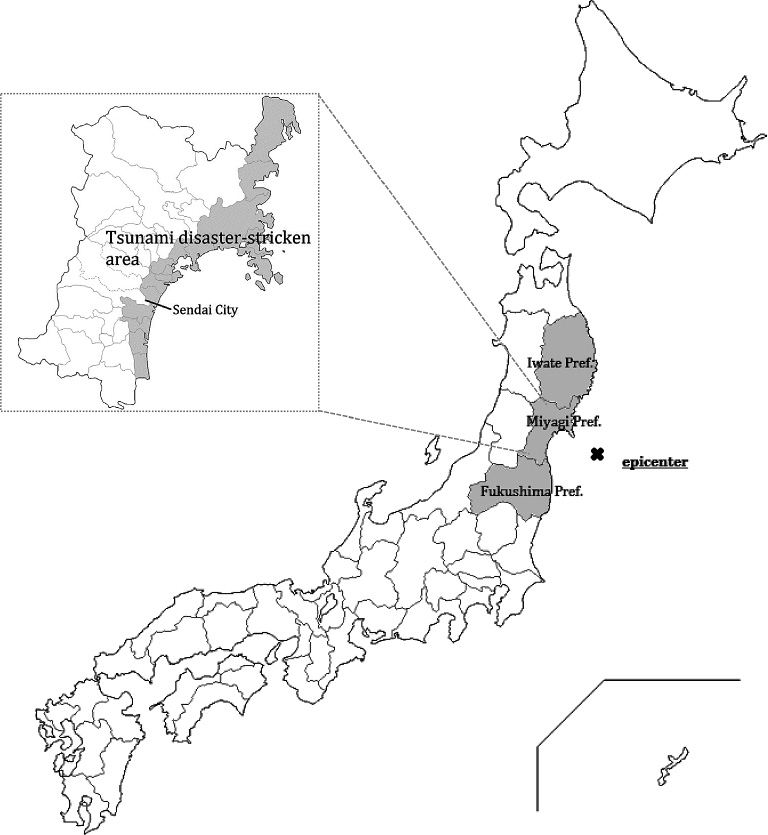

The Great East Japan Earthquake occurred on March 11, 2011, at 14:46 Japan Standard Time (JST). The maximum seismic intensity level reached seven near the earthquake’s epicenter (Fig. 1), and the ensuing tsunami caused enormous damage to the Pacific coast, particularly in Iwate, Miyagi, and Fukushima Prefectures. Individuals pronounced dead or missing within Iwate, Miyagi, and Fukushima Prefectures accounted for more than 99% of the total casualties of this disaster.

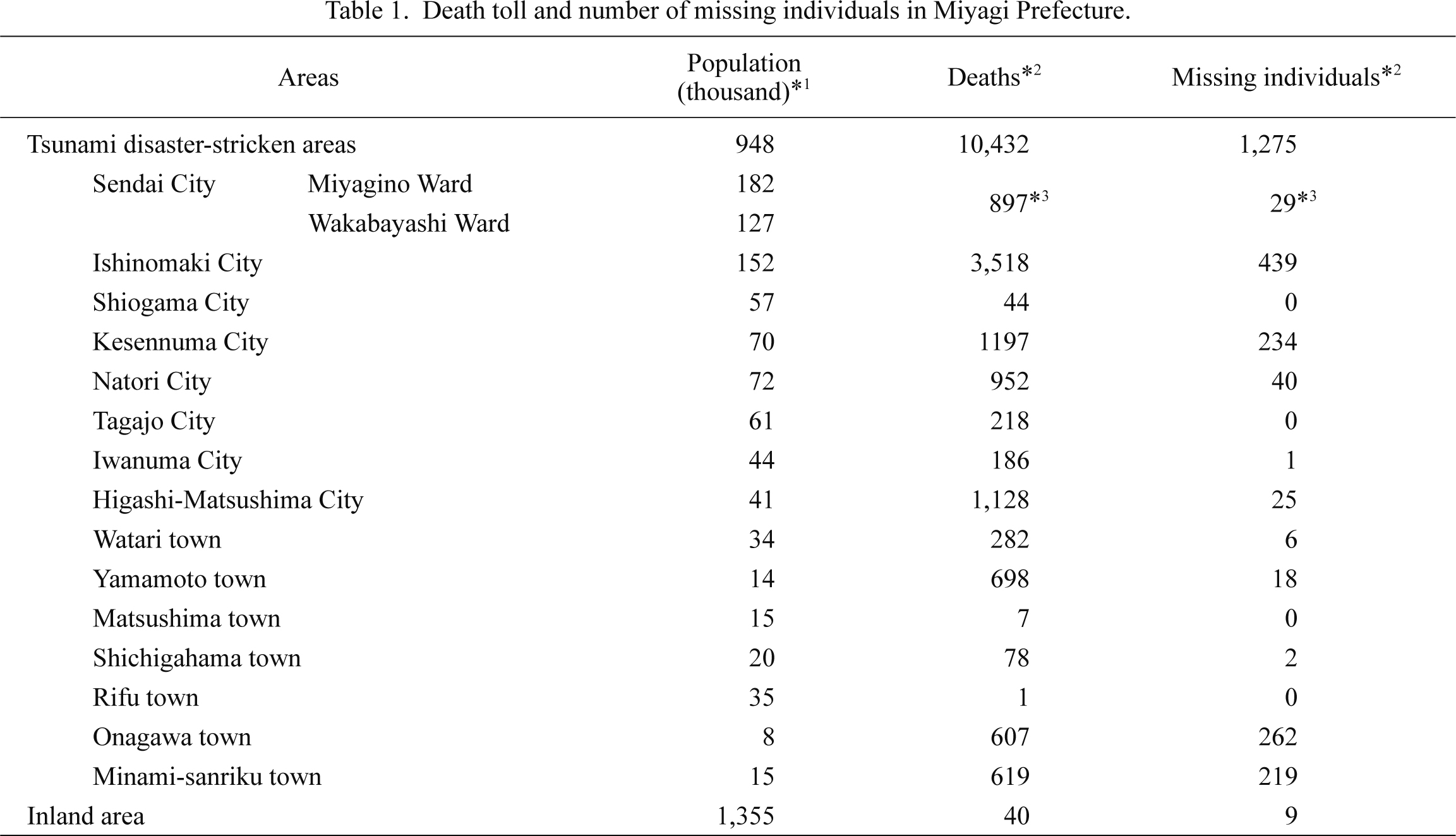

In this disaster, the death toll and numbers of missing individuals varied markedly between inland and the tsunami disaster-stricken area along the coast (Table 1). In order to examine differences in the trends of suicide rates between the two areas, we defined the tsunami disaster-stricken area in this study as comprising the 16 municipalities in Miyagi Prefecture, which faced the Pacific Ocean, although the tsunami caused severe damage in three prefectures. Inland areas were defined as other municipalities (excluding coastal ones) in Miyagi Prefecture that were damaged by the earthquake (Fig. 1). These definitions excluded Iwate and Fukushima Prefectures for the following reasons: 1) the majority of victims in Fukushima were relocated to temporary housing outside the disaster-stricken areas due to their proximity to the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant; 2) the population within the tsunami disaster-stricken areas in Iwate was much lower than that of inland areas, making it difficult to compare these two areas; and 3) tsunami damage to coastal areas of Iwate varied by area (e.g., relatively small damage in Northern areas and severe damage in Central and Southern areas). By focusing on Miyagi Prefecture, the following strengths were noted: 1) the difference in population migration from the tsunami disaster-stricken area was comparatively low; 2) the populations of these two areas were similar (tsunami disaster-stricken area: 0.95 million and inland: 1.36 million); and 3) damages incurred in each coastal municipality of Miyagi Prefecture were relatively equal (Table 1).

Epicenter of the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami Disaster-Stricken Areas.

The Great East Japan Earthquake occurred on March 11, 2011, generating a massive tsunami. The tsunami reached a maximum height of 9.3 m and traveled up to 10 km inland. The tsunami disaster-stricken area was defined in this study as comprising 16 municipalities proximal to the Pacific Ocean in Miyagi Prefecture. Inland areas were defined as other municipalities in Miyagi Prefecture that were damaged by the earthquake.

Death toll and number of missing individuals in Miyagi Prefecture.

*1As of March 31, 2012. Cabinet Office, Government of Japan.

*2As of March, 2014. Fire and Disaster Management Agency of Japan.

*3Death toll and number of missing individuals were combined Miyagino and Wakabayashi wards.

Tsunami disaster-stricken area: Sixteen coastal municipalities in Miyagi Prefecture.

Inland area: Other municipalities in Miyagi Prefecture.

Monthly suicide data (based on suicide date and residential place) were collected nationally, as well as for each municipality in Miyagi Prefecture from February 2009 to February 2014. These data were obtained from the open-access website of the Japanese National Police Agency (http://www8.cao.go.jp/jisatsutaisaku/toukei/index.html (in Japanese)) which provided data from January 2009. These data were based on the residential place just before the suicide, and not before this disaster. Basic annual population data from the resident registry for each municipality (as of March 31, 2009-2013) were also collected from the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications Statistics Bureau.

Monthly suicide data were obtained from the open-access websites in the form of de-identified, anonymous data. According to epidemiological research guidelines set forth by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology, as well as the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare, ecological studies are exempt from ethical review. Accordingly, review by an ethics committee was not required.

Data analysisWe calculated annualized suicide rates by summing the monthly suicide number of 16 coastal municipalities. This was then divided with the Basic Resident Register population as summed up by 16 coastal municipalities. These values were annualized by multiplying them with 12.

*Annualized suicide rates = {Σ (monthly suicide number in tsunami disaster-stricken or inland area)/Σ (basic resident population in tsunami disaster-stricken or inland area)}*12

The analysis of data on monthly suicide rates was conducted via the following three methods: 1) exponential smoothing time-series modeling was used to observe the trend of suicide rates after this disaster; 2) period analysis was used to divide the total 60-month study period into five segments (with 12 months in each period, from March 2009 to February 2014), in which suicide rates were compared to corresponding national averages using a Poisson distribution; and 3) analysis of suicide rates by age group.

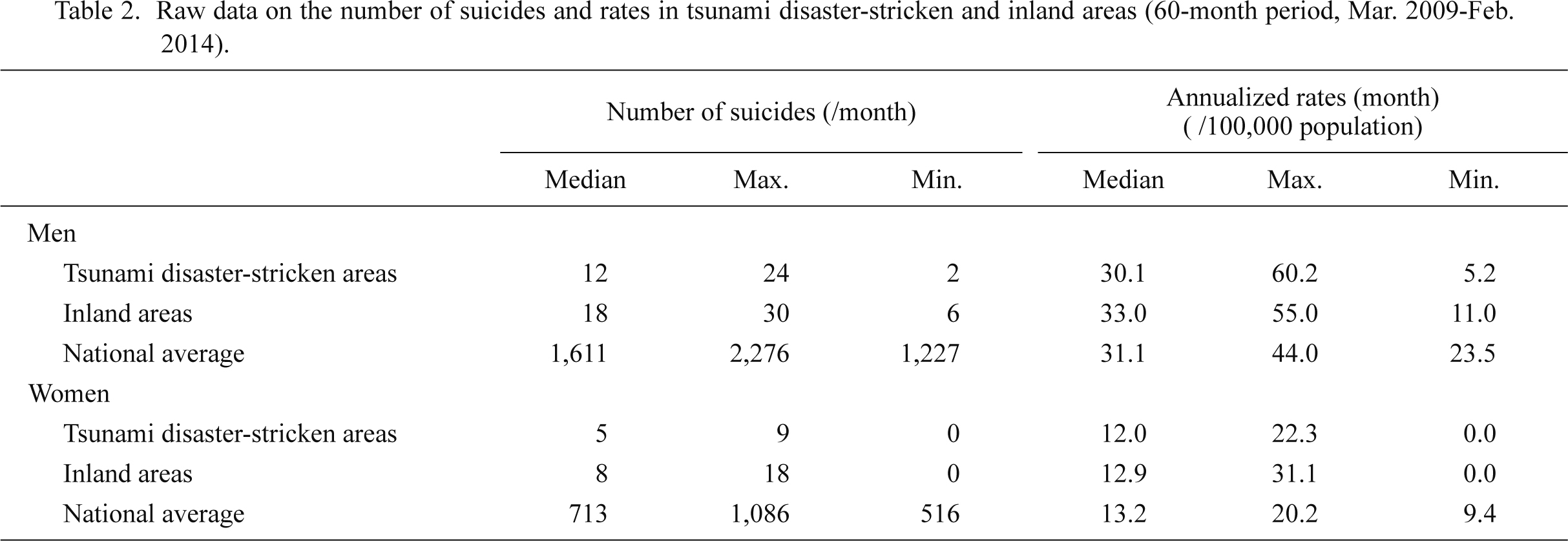

Basic statistics on suicide rates in tsunami disaster-stricken and inland areas are given in Table 2. Based on exponential smoothing time-series modeling, in the tsunami disaster-stricken areas, male suicide rates during the initial post-disaster period were significantly lower than the national average, and then increased in the next 15 months. Post-disaster male suicide rates in the inland areas decreased during the initial 7 months, but subsequently increased and exceeded the national average. Female post-disaster suicide rates in the tsunami disaster-stricken areas did not change compared to the national average, although suicide rates decreased slightly during the following 18 months. Female suicide rates in the inland areas exceeded the national average immediately following the disaster. The increase in national suicide rates immediately after the disaster in both men and women was an important issue; however, we do not have enough data or information to pinpoint specific reasons to explain this trend (Fig. 2).

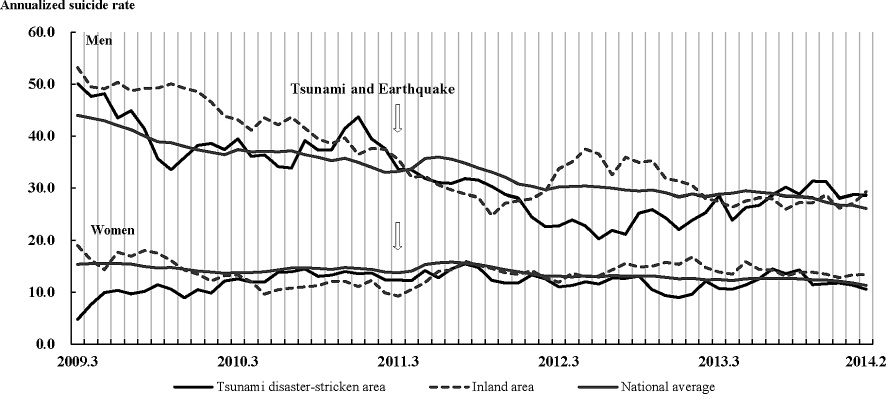

Compared to the national average via a Poisson distribution test, pre-disaster male suicide rates in the tsunami disaster-stricken area did not differ significantly from the national average (Fig. 3). In the initial 12-month post-disaster period (March 2011 to February 2012), male suicide rates were significantly lower than the national average (p = 0.002), and remained significantly lower during the second 12-month period (March 2012 to February 2013) (p = 0.026). During the third 12-month period (March 2013 to February 2014), post-disaster male suicide rates were equivalent to the national average. In the inland areas, male suicide rates were significantly lower than the national average during the initial 12-month post-disaster period (p = 0.008), but these rates subsequently increased to significantly exceed the national average (the period from March, 2012 to February, 2013) (p = 0.032). In contrast, the post-disaster female suicide rates did not show significant changes as compared to the national average (Fig. 3).

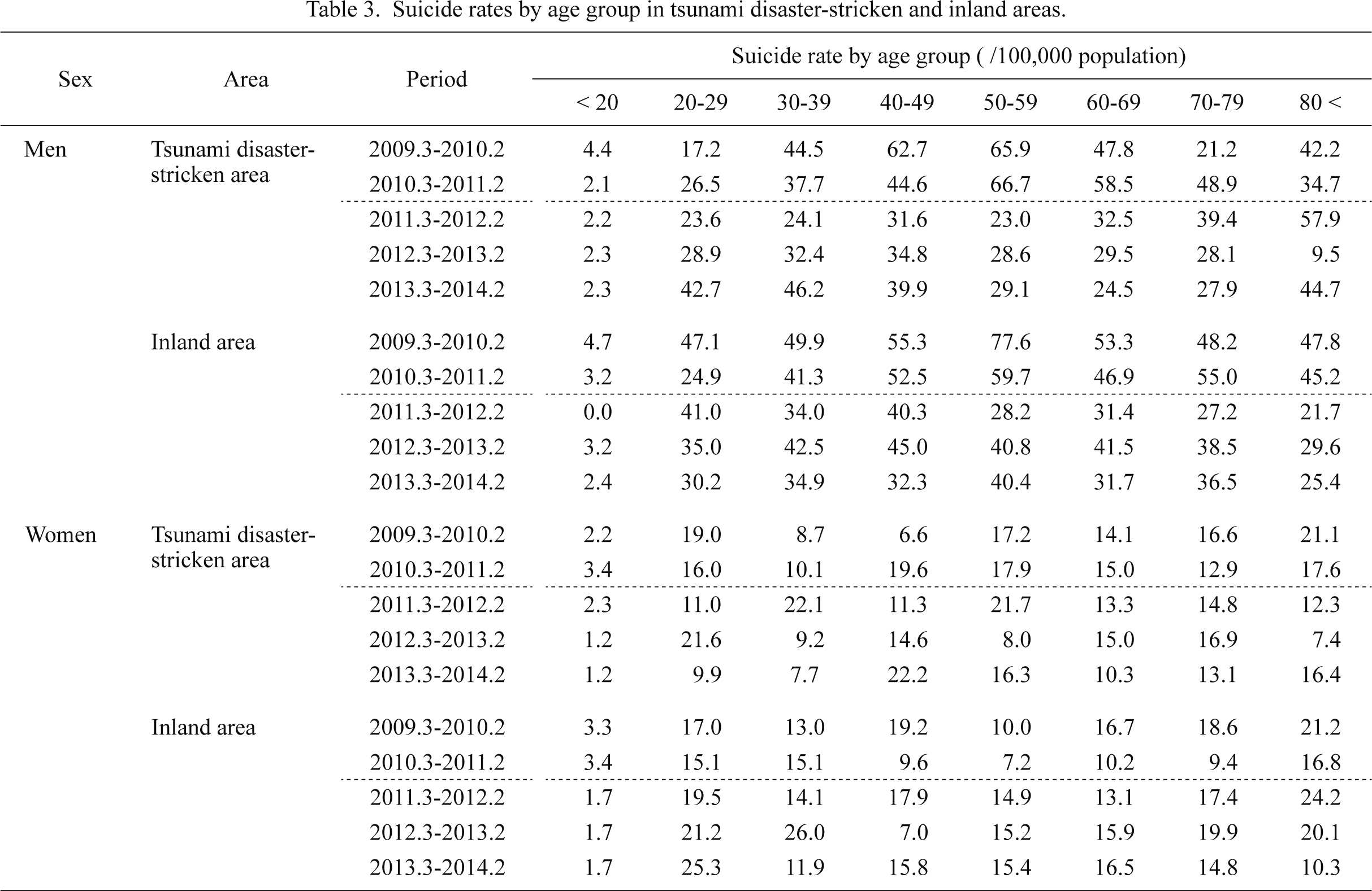

Analysis by age group showed that suicide rates for men aged 40-60 years decreased greatly during the initial post-disaster period (March 2011 to February 2012), not only in the tsunami disaster-stricken area, but also in the inland areas. Suicide rates in the inland areas increased during the subsequent post-disaster period, while those in the tsunami disaster-stricken area remained low. Suicide rates increased among individuals aged 20-29 years, as well as those aged ≥ 80 years, in the tsunami disaster-stricken area during the third post-disaster period (March 2013 to February 2014) (Table 3).

Raw data on the number of suicides and rates in tsunami disaster-stricken and inland areas (60-month period, Mar. 2009-Feb. 2014).

Tsunami disaster-stricken area: Sixteen coastal municipalities in Miyagi Prefecture.

Inland area: Other municipalities in Miyagi Prefecture.

Changes in Suicide Rates in Tsunami Disaster-Stricken and Inland Areas.

Trends in suicide rates in tsunami disaster-stricken and inland areas are shown. Suicide rates are depicted per 100,000 people. The down arrow corresponds to the occurrence of the tsunami following the Great East Japan Earthquake.

Annualized suicide rate: Monthly suicide number/population* 100,000* 12.

Tsunami disaster-stricken area: Sixteen coastal municipalities in Miyagi Prefecture.

Inland area: Other municipalities in Miyagi Prefecture.

Comparison of National Suicide Rates and Suicide Rates within Tsunami Disaster-Stricken and Inland Areas.

Suicide rates in tsunami disaster-stricken and inland areas are shown by post-disaster period. Suicide rates are depicted per 100,000 people. The down arrow corresponds to the occurrence of the tsunami following the Great East Japan Earthquake. Comparison between post-disaster rates and the national average were conducted with a Poisson distribution.

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, Poisson distribution test.

Annualized suicide rate: Monthly suicide number/population* 100,000* 12.

Tsunami disaster-stricken area: Sixteen coastal municipalities in Miyagi Prefecture.

Inland area: Other municipalities in Miyagi Prefecture.

Suicide rates by age group in tsunami disaster-stricken and inland areas.

Tsunami disaster-stricken area: Sixteen coastal municipalities in Miyagi Prefecture.

Inland areas: Other municipalities in Miyagi Prefecture.

The present study has several noteworthy limitations. First, the 2-year period before this disaster might have been too short to determine suicide trends prior to the disaster. However, we were only able to collect data from January 2009 from the open-access website, which did not allow us to obtain detailed data from each municipality prior to 2008. Consequently, data collection for pre- and post-disaster periods was not completely symmetrical. The second limitation is the method used to calculate annualized suicide rates. Because we were unable to obtain data for the monthly basic resident population from each municipality, we used annual basic resident population to estimate suicide rates. Third, the tsunami disaster-stricken and inland areas had higher suicide rates than the national average, despite the fact that the rates in this area had decreased prior to the disaster. In fact, suicide rates in Japan increased sharply in 1998 and have remained relatively high ever since. Given this trend, various and continuous suicide prevention measures had already been implemented for a decade before the disaster occurred. These efforts may have influenced the observed changes in suicide rates. Notably, the exponential smoothing time-series model used in the present study did not take into account the pre-disaster baseline downward trends in suicide in tsunami disaster-stricken and inland areas. However, we decided to use this model because our study aimed to obtain a rough estimate, rather than a precise validation of the suicide trends after this disaster. Finally, some victims were relocated to areas outside the tsunami disaster-stricken area, possibly leading to underestimation of the findings. However, Cabinet Office, Government of Japan (2013) reported that 76.7% of victims within the tsunami disaster-stricken areas in Miyagi Prefecture were relocated to undamaged areas within the same municipalities (http://www.stat.go.jp/info/shinsai/ (only in Japanese)). According to reports from the Sendai City Office, 82.5% of victims in Sendai were relocated to undamaged tsunami disaster-stricken areas. Therefore, the suicide rates in the tsunami disaster-stricken area may have been underestimated due to the relocation of many of the affected residents. In addition, potential bias may exist in these results.

Despite the fact that associated data regarding changes in suicide rates are limited, this study found that post-disaster suicide rates among middle-aged men decreased, not only in the tsunami disaster-stricken area, but also in the inland areas. These findings were similar to those observed in studies following the 1995 Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake (6,437 victims), which resulted in the collapse of many houses and buildings in the Hanshin area in cities around Kobe; thus, most of those victims were crushed to death or developed crush syndrome (Nishio et al. 2009; Furukawa and Arai 2011; Ishigaki et al. 2013). A previous study of the 2008 global economic recession reported, “Men aged 45-64 were most affected in American countries. Rises in national suicide rates in 2009 seemed to be associated with the magnitude of increases in unemployment” (Chang et al. 2013). The Miyagi Labor Bureau reported that, in both tsunami disaster-stricken and inland areas, the ratio of effective job offers has increased consistently following the disaster. Incidentally, effective job offers is defined by the number of workers whom various companies are seeking as regular or temporary staff. These studies and reports have indicated that changes in economic situations following disasters may impact the suicide rates of middle-aged men. Given that stable economic status is a protective factor against suicide, increasing the number of effective job offers is likely to positively impact suicide rates during the initial post-disaster period.

There is often a decrease in non-fatal suicidal behaviors in the immediate aftermath of a disaster, which has been referred to as the “honeymoon period” (Madianos and Evi 2010). Another study reported that the feeling of “pulling together” during a natural disaster reduced interpersonal risk factors associated with the desire for suicide (Gordon et al. 2011). Following the Great East Japan Earthquake, more intensive mental healthcare services were provided in tsunami disaster-stricken areas, as compared to the inland areas during the early post-disaster period. Although specific reasons for trends in suicide rates were not determined in this study, the initial decrease in post-disaster suicide rates might be attributed to the aforementioned protective factors, phenomena, and intensive mental healthcare activities.

Although male suicide rates in the tsunami disaster-stricken areas initially decreased post-disaster, a delayed increase was noted after roughly a year and a half. Kessler et al. (2008) reported a delayed increase in suicidal ideation after Hurricane Katrina hit the United States. That study found an increase in suicidality within the first year after the hurricane, which persisted for the initial two-year period but tended to decrease after that (Kessler et al. 2008). This trend may have occurred in the inland areas earlier than in the tsunami disaster-stricken areas, where male suicide rates increased to exceed the national average at eleven months post-disaster. Although the reasons for the relatively early increase in male post-disaster suicide rates in the inland areas were not clear, the damage caused by a huge earthquake may have played a role. Thousands of homes were completely destroyed in the inland areas, despite the relatively low number of causalities.

Although suicide rates decreased during the initial post-disaster period, male suicide rates showed a delayed increase in tsunami disaster-stricken areas as of mid-2012, similar to that observed in a previous study of Hurricane Katrina. In tsunami disaster-stricken areas, both male and female post-disaster suicide rates showed a delayed increase after one and a half years. It is possible that further increases in suicide rates will occur in the tsunami disaster-stricken areas in the future. Such increases may greatly exceed the national average if the trends observed in inland areas were to continue. However, in actuality, suicide rates in tsunami disaster-stricken areas have decreased by the end of this study period, and did not exceed the national average greatly, as compared to the inland areas. Importantly, suicide rates in tsunami disaster-stricken areas did not greatly exceed those in inland areas, despite indications of the delayed increase. One reason for this discrepancy may be the presence of intensive and long-term mental healthcare services in the tsunami disaster-stricken areas. According to Miyagi Prefectural Government reports, countless long-term mental healthcare services were provided in tsunami disaster-stricken areas, while fewer mental healthcare services were provided in the inland areas. These differences may have affected the suicide rates in both areas.

In conclusion, male suicide rates in tsunami disaster-stricken areas were significantly lower than the national average during the initial post-disaster period and began to increase after two years. Although a similar situation was also observed in inland areas, male suicide rates in inland area increased after one year and exceeded the national average greatly. These findings indicate the importance of providing intensive, long-term mental healthcare services following disasters. Remarkably, at three years after the Great East Japan Earthquake and tsunami, many survivors still live in temporary housing and face various challenges to rebuild their lives. It is therefore possible for another increase in suicide rates to occur in tsunami disaster-stricken areas due to the continued stress of being unable to rebuild life as it was before the disaster. Trends in suicide rates need to be carefully monitored, and vigorous mental healthcare services should be provided on an ongoing basis.

This study received the support of a grant from the Sendai City Public Health Research Project. This grant is offered to staff members who work in the Sendai City Office in their efforts to contribute to policy planning. It is thus expected that policy planning related to mental health care and suicide measures following the Great East Japan Earthquake will be implemented in light of the present study findings.

The authors declare no conflict of interest, although the present study was supported in part by the grant from the Sendai City Public Health Research Project, as clarified in Acknowledgments. In addition, staff members of the Sendai City governmental office were involved in mental health activities in disaster-stricken areas of Sendai City. However, the present study targeted not only residents of Sendai City but also those of other cities and towns in Miyagi Prefecture, who did not receive mental health services from Sendai City. We therefore assure that research neutrality has been retained.