- Issue 6 Pages 735-

- Issue 5 Pages 569-

- Issue 4 Pages 439-

- Issue 3 Pages 305-

- Issue 2 Pages 103-

- Issue 1 Pages 1-

- |<

- <

- 1

- >

- >|

-

2018 Volume 127 Issue 6 Pages Cover06_01-Cover06_02

Published: December 25, 2018

Released on J-STAGE: January 30, 2019

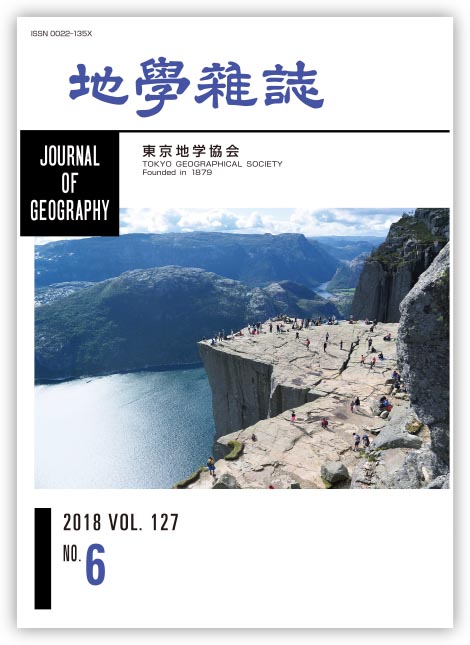

JOURNAL FREE ACCESSThe Lysefjord is a fjord located in Rogaland county, southwestern Norway. The length of the fjord is about 42 km and it is situated 25 km east of Stavanger city along the North Sea. The name ‘Lysefjord’ means light fjord because the wall of the fjord is composed of light-colored granite rocks. The fjord was eroded by the action of glaciers during the last glacial age, with cliffs curving more than 1000 m on both sides. The cliff height is about 600 m and the water depth is more than 400 m around Preikestolen, which is shown in the photograph. However, near Forsand, where the Lysefjord meets another fjord, the water depth is only 13 m, because of the deposition of till sediment of glacial origin. Preikestolen is the most popular sightseeing spot along the Lysefjord because of the spectacular vertical cliffs. The name Preikestolen means a church pulpit. BASE jumpers often leap from the cliff. Preikestolen is not located in an easily accessible place. It takes about one hour from Stavanger city by ferry and bus, then two hours hard walk.

(Photograph & Explanation: Hideaki MAEMOKU; August 16, 2014)

View full abstractDownload PDF (2388K)

-

Mayumi MIYAZAKI, Daisuke ISHIMURA2018 Volume 127 Issue 6 Pages 735-757

Published: December 25, 2018

Released on J-STAGE: January 30, 2019

JOURNAL FREE ACCESSMarine terraces on the northern Sanriku Coast are mapped, verifying their emergent times with a tephra analysis to provide accurate information on long-term coastal uplift along the Sanriku Coast. The results contradict the conventional view of century-long subsidence and coseismic subsidence associated with the 2011 Tohoku-oki earthquake. Eight visible tephra layers are found to cover the Taneichi surfaces reported as Marine Isotope Stage (MIS) 5 marine terraces in previous research on the northern Sanriku Coast, and these correlate with To-H, To-Of, To-G, To-Ok2, To-AP, To-CP, Toya, and ZP2 tephra layers previously identified at the Kamikita Plain based on petrographic properties. Consequently, because the Toya tephra (ca. 112-115 ka) covers marine sand and/or gravel beds composing the terraces, they are confirmed to be MIS 5e marine terraces. The paleo-shoreline of the MIS 5e marine terraces is inferred, considering topographic profiles and aeolian deposits covering terrace surfaces, and their heights are measured with high-resolution digital elevation models to be ca. 40 m above the present sea level at the Kamikita Plain and ca. 20-30 m at the northern Sanriku Coast. In addition, uplift rates from the Kamikita Plain to the northern Sanriku Coast are estimated to be 0.3 mm/yr and 0.1-0.2 mm/yr, respectively, tending to gradually decrease toward the south, and may be subject to subsidence further south along the southern Sanriku Coast.

View full abstractDownload PDF (6964K) -

Yudzuru INOUE, Shinji SUGIYAMA, Hisashi OIWANE, Toshiro YAMANAKA, Chit ...2018 Volume 127 Issue 6 Pages 759-774

Published: December 25, 2018

Released on J-STAGE: January 30, 2019

JOURNAL FREE ACCESSThe age when initiation of Pleioblastus linearis (bamboo) community formation with Andosols was initiated and diagnostic properties of Andosols after the ca. 7.3 cal ka BP Kikai-Akahoya (K-Ah) eruption are examined in Takeshima, Mishima Village, Kagoshima, Japan. Takeshima forms the northern rim of the Kikai caldera. It fulfills the effective growth conditions (bio-climatic conditions in humid subtropics; Cfa, and geomorphological conditions through its location on undulating terrain) for the bamboo community. Vegetation succession does not progress because lucidophyllous forest vegetation cannot invade due to the high-density roots of the bamboo community, and is also inhibited by the influence of volcanic gases (mainly SO2). Accordingly, bio-mass derived from bamboo (Pleioblastus linearis) becomes the main source of humus for Andosols formation, and the genesis of Andosols is thereby sustained in Takeshima. Takeshima is near the eruption source vent of K-Ah tephra, which includes abundant volcanic glass, the main parent material of Andosols, needed to hold humus. That is, active forms of Si, Al, and Fe, which result from the weathering of volcanic glass, retain the humus that derives from bamboo (Pleioblastus linearis). As a result, allophanic Andosols are formed in Takeshima: they have silandic properties (Sio content of ≥ 60 g kg−1 or Alp/Alo of < 0.5) that meet the requirements for Andosols. Macro-charcoal particles (> 500 μm) are hardly detected in the humic horizon of Takeshima. This low presence indicates that burning was not carried out to maintain the grass (bamboo) vegetation (Pleioblastus linearis). Past vegetation in Takeshima is estimated using a phytolith analysis of samples postdating the K-Ah eruption: the bamboo (Pleioblastus sect. Nipponocalamus type) gradually increased until the present. This trend indicates that the bamboo community successfully outcompeted lucidophyllous forest vegetation and bamboo was sustained in the vegetation community for a long period.

View full abstractDownload PDF (3139K) -

Tomoyo TOBITA, Yukio ISOZAKI, Ryutaro HAYASHI2018 Volume 127 Issue 6 Pages 775-794

Published: December 25, 2018

Released on J-STAGE: January 30, 2019

JOURNAL FREE ACCESSTo clarify environmental and biological responses to the extinction-related global change that occurred during the Late Guadalupian (Permian), high-resolution lithostratigraphy is analyzed of the uppermost part of the Capitanian (Upper Guadalupian) shallow-marine Iwaizaki Limestone in the South Kitakami Belt, NE Japan, deposited as a patch reef on a continental shelf at the northeastern extension of South China, with various shallow marine fossils, e.g., rugose corals, fusulines, brachiopods, crinoids, and calcareous algae. The topmost ca. 40 m-thick interval of the limestone (Unit 8) is composed of interbedded limestone and mudstone, which are subdivided into the following four distinct subunits: Subunit 8-A of limestone-dominated alternation with nodular limestone, Subunit 8-B of mudstone-dominated alternation of limestone and mudstone, Subunit 8-C of thickly bedded limestone, and Subunit 8-D of calcareous mudstone, in ascending order. Subunit 8-D is covered directly with a thick black mudstone unit mostly of the Lopingian age. A clear pattern of step-wise disappearance of shallow-marine, tropically-adapted fossil biota, e.g., large bivalves (Alatoconchidae), rugose corals (Waagenophyllum), and large-tested fusulines (Lepidolina), is detected in the topmost Unit 7 and Unit 8 (8A to 8B), regardless of significant fluctuations of water-depth within this interval. The overall stratigraphic change in lithofacies within Unit 8 indicates a deepening trend, which was probably controlled by subsidence of the basement. Nonetheless, tectonic-driven subsidence led to the preservation of continuous stratigraphic records of the topmost Iwaizaki Limestone with the collapsing history of a patch reef, despite a global sea-level drop across the G-L boundary. The appearance of global cooling probably led to the extinction of warm water-adapted benthic tropical biota and the collapse of a reef complex during the Capitanian.

View full abstractDownload PDF (4630K)

-

Shigeru SUEOKA, Koji SHIMADA, Tsuneari ISHIMARU, Tohru DANHARA, Hideki ...2018 Volume 127 Issue 6 Pages 795-803

Published: December 25, 2018

Released on J-STAGE: January 30, 2019

JOURNAL FREE ACCESSThermochronometric analyses are applied to Kojaku and Tsuruga bodies of Kojaku granite, southwest Japan, to reconstruct detailed cooling histories and to reveal geo- and thermo-chronologic relationships of the two bodies. Zircon U–Pb ages are estimated to be 69.2-68.0 Ma, suggesting coeval emplacement of the two bodies. These results support the previous petrographic classification of Kojaku granite in terms of geochronology. Fission-track (FT) ages obtained are 59.6-53.0 Ma and 44.8-20.9 Ma for zircon and apatite, respectively. Zircon FT lengths imply rapid cooling, so the heterogeneous zircon FT ages are attributable to differences in the timing of cooling just after intrusion related to the distance from the margin of the granite body. Apatite FT lengths suggest more complicated cooling histories; samples of the Tsuruga body reflect long-term denudation whereas those of the Kojaku body might have been reheated by volcanic activity prior to ∼20 Ma. Plagioclase K–Ar dating is also performed on different lithofacies of a basaltic dike intruding into the Tsuruga body. The ages are inferred to be 20.1 ± 0.5 Ma for both lithofacies. Even if the two lithofacies were formed by multiple intrusions, the time gap must have been short, probably less than 105 years.

View full abstractDownload PDF (1874K)

-

Naotoshi YAMADA, Michiko YAJIMA2018 Volume 127 Issue 6 Pages 805-822

Published: December 25, 2018

Released on J-STAGE: January 30, 2019

JOURNAL FREE ACCESSJohannes Justus Rein (1835-1918), a German geographer, stayed in Japan during the period 1874-1875 by order of the Prussian Royal Government. He extensively researched not only the industry and commerce of Japan, which was the main task with which he was entrusted by the government, but also the geography, geology, botany, zoology, and meteorology of Japan, as well as other scientific fields, based upon his own interests. “Dr. J. Rein's Reise in Nippon, 1874,” which we have now translated into Japanese, is his first paper about Japan, and was written mainly from the latter viewpoint. From May to July 1874, he traveled to central Japan along the Tokaido, Nakasendo, Hokurikudo, and Hokkokukaido highways, returning via the Nakasendo highway, in a clockwise round trip through mountainous regions, where he observed the mountains, rivers, plants, animals, climates, and lives of inhabitants along the roads. In this paper, he presents a topographic division of the region, proposing that “the Japanese Snow-ridge Range”—roughly corresponding to the present-day Hida Mountain Range—is the most important mountain range, and mentions its climatic significance. During the trip, he climbed volcanoes such as Mt. Hakusan, Mt. Asama, and Mt. Hakone, and also collected many plant specimens.

View full abstractDownload PDF (1666K) -

Hiroshi MATSUYAMA2018 Volume 127 Issue 6 Pages 823-833

Published: December 25, 2018

Released on J-STAGE: January 30, 2019

JOURNAL FREE ACCESSA period with less than average precipitation on Chichi-jima and Haha-jima in the Ogasawara (Bonin) Islands between 2016 to 2017 was compared to 2018 (normal year), based on field surveys conducted in March 2017 and February 2018. Water consumption showed a six-day cyclic variation, reflecting the voyage schedule of the marine vessel Ogasawara-maru connecting Chichi-jima and central Tokyo. Water consumption increased on the day Ogasawara-maru arrived at Chichi-jima, because the number of passengers sometimes corresponded to about 30% of number of residents on Chichi-jima. Compared to Chichi-jima, annual precipitation on Haha-jima was about 100 mm greater during the period 2007-2017, along with distinctly greater precipitation in May compared to April and June. In addition, precipitation on Haha-jima in August was the highest among all months. Even during a severe drought in 2016-2017, precipitation in August 2016 was greater than the average from 2007 to 2017 on Haha-jima, recovering water stored by the Chibusa dam which supplies drinking water on Haha-jima. The effective water storage per capita on Haha-jima is 1.5 times more than that on Chichi-jima, which in some part resulted in the temporal change in the percentage of water storage always being larger on Haha-jima. Both on Chichi-jima and Haha-jima, people tried to overcome the difficult situation of the severe drought, reflecting efforts by the local government to communicate the need to save water.

View full abstractDownload PDF (3564K) -

Editorial Committee of History of Geosciences in Japan, Tokyo Geograph ...2018 Volume 127 Issue 6 Pages 835-860

Published: December 25, 2018

Released on J-STAGE: January 30, 2019

JOURNAL FREE ACCESSThe development of geomorphology, human geography, history and methodology of geography, regional geography, and geographic education in Japan from 1945 to 1965 are described. Research objectives and methodologies of geomorphology diversified during this period. A series of natural disasters triggered by earthquakes and typhoons raised social demands for disaster prevention and national land-use management. Full-scale geomorphic studies, fused with geology and engineering, started. Historical geomorphology of lowland plains and process geomorphology began to develop, adding to traditional descriptive geomorphology. The Research Institute for Natural Resources and the Geographical Survey Institute contributed to the postwar reconstruction of geomorphology. Aerial photo interpretation and quantitative land surface analyses developed. A hierarchical landform classification for lowland plains was established and applied to many plains in Japan and developing countries, in order to predict areas subject to flooding and land use planning. The postwar education system increased the number of physical geographers. They contributed to the land classification of Japan as a whole and increased interest in Quaternary environmental changes such as climate and sea level changes, as well as crustal movements, which have produced landform diversity. In 1956, they established the Japan Association for Quaternary Research in cooperation with geologists, anthropologists, and archaeologists. Human geographical research in postwar Japan was far more active and diverse than in the prewar years. This was partly the result of an increase in academic posts devoted to human geography in relation to curriculum reforms in secondary and higher education. Initially, settlement geography was a major field of study. Subsequently, historical geography and economic geography were gradually popularized with the establishment of specialized academic societies, which were dedicated to both fields of study. Among the newly emerging fields were urban, social, and cultural geography. The history and methodology of geography were viewed as overarching fields connected to both physical and human geography. Despite ongoing diversification within geographical research, various topics in these fields were addressed by Japanese geographers. This reflected long-lasting debates concerning the disciplinary identity of geography itself. Regional geography and geographic education concerned both physical and human geography. These research fields were invigorated because of the relative importance of geography in Japan's secondary and higher education systems up to the early 1960s.

View full abstractDownload PDF (725K)

- |<

- <

- 1

- >

- >|