2017 Volume 125 Issue 3 Pages 141-151

2017 Volume 125 Issue 3 Pages 141-151

The upper incisor lingual morphology of the late Miocene Greek hominoid Ouranopithecus macedoniensis was almost unknown, as the described earlier maxillary remains preserve only worn incisors. During the most recent excavations in the type locality of Ouranopithecus, Ravin de la Pluie (RPl) of Axios Valley (Macedonia, Greece), four little-worn upper central incisors were recovered. This material and a few additional worn upper incisors, discovered recently, are described and compared in this article. Even though a morphological comparison with the old RPl material, lacking unworn or little worn incisors, is impossible, the metrical comparison and the monospecific character of the RPl hominoid sample suggest that the described incisors can be assigned to Ouranopithecus macedoniensis. The described upper central incisors are separated in two size-groups which in general have similar morphology except for some minor differences such as the presence of a pronounced mesial lingual pillar in the small-sized specimens. The observed significant size difference among the studied incisors is attributed to the strong sexual dimorphism of Ouranopithecus, which is also well expressed in the other teeth. The lingual morphology of the upper incisors of Ouranopithecus are not identical to those of extant great apes, though they have some similarities with those of the African great apes (Gorilla and Pan), while they are clearly different from those of the Asian great ape (Pongo). Even though they have some morphological similarities, the O. macedoniensis central incisors are probably not identical to those of the Eurasian Miocene hominoids; the most similar central incisor is that of Ouranopithecus turkae. Among the known African Miocene hominoids, Nakalipithecus upper central incisor is quite similar in morphology and size to that of Ouranopithecus.

Since the beginning of the 1970s, the late Miocene mammal locality Ravin de la Pluie (RPl) of Axios Valley (Macedonia, Greece) has been known for the presence of the hominoid Ouranopithecus macedoniensis. Several maxillary and mandibular remains of this taxon have been unearthed during the last 45 years, allowing a good understanding of its postcanine teeth morphology and features (Bonis and Melentis, 1977, 1978; Bonis et al., 1990; Bonis and Koufos, 1993; Bonis et al., 1998; Koufos and Bonis, 2004, 2006). In RPl, O. macedoniensis is associated with a rich mammalian fauna, where bovids and giraffids predominate (>60% of the fauna), either in the number of the determined specimens or the minimum number of individuals (Bonis et al., 1992). The RPl fauna is older than the known Turolian mammal faunas of Greece and suggests a correlation with the European land mammal zone MN 10, corresponding to the late Vallesian. The magnetostratigraphic study of the Axios Valley late Miocene deposits indicates an estimated age of ~9.3 Ma for RPl. The same hominoid has also been found at the locality Xirochori 1 (XIR)—about 1.5 km from RPl—also correlated to the late Vallesian (MN 10). Magnetostratigraphic correlations suggest an estimated age of ~9.6 Ma for XIR (Sen et al., 2000; Koufos, 2013 and references therein). O. macedoniensis is also known from the locality Nikiti 1 (NKT), about 150 km south-west of the Axios Valley, the fauna of which indicates a terminal Vallesian age, ranging from 9.3 to 8.7 Ma [Koufos et al. (2016a) and references therein].

Despite the rich dental collection of O. macedoniensis, the maxillary remains are scanty and the morphology of some teeth is virtually unknown. The upper incisors of O. macedoniensis were only known from two previously described maxillae from RPl. However, these are heavily worn and their lingual traits are invisible (Bonis and Melentis, 1978; Bonis et al., 1998). The upper incisors of the partial skull XIR-1, from Xirochori 1, are also worn and cannot yield any information on their lingual morphology (Bonis and Koufos, 1993). During recent field work we recovered some isolated upper incisors, four of which are little worn and preserve well the lingual morphology. The present article describes the new incisor remains in reference to the previous material and compares them with those of the extant and Miocene hominoids.

The described incisors are housed in the Laboratory of Geology and Palaeontology, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki (LGPUT). The material was measured with a digital caliper and the measurements are given in millimeters with an accuracy of 0.1 mm; estimated values are given in parentheses. The previously described material of O. macedoniensis from RPl, also housed in LGPUT, including the male maxillae RPl-128 and RPl-775 (Bonis and Melentis, 1978; Bonis et al., 1998) and the male partial skull with the maxilla XIR-1 from Xirochori 1 (Bonis and Koufos, 1993), is used as comparative material. The comparative material of the modern hominoids includes the collections of the Senckenberg Museum of Natural History, Frankfurt (SMF) and the Museum Nationale d’Histoire naturelle of Paris (MNHNP); only incisors of the 1st and 2nd wear stage (see below for the definition of wear stages) are used. The studied modern hominoids belong to Gorilla gorilla (3 individuals), Pan troglodytes (7 individuals), and Pongo pygmeaus (5 individuals) and are all mentioned in the text with their generic name. The nomenclature for the lingual traits of incisors follows that of Pilbrow (2006) (Figure 1). Following this author, the incisors preserving lingual traits are divided in three dental wear stages: 1, a thin dentine strip exposed along the incisal margin; 2, a thick dentine strip exposed along the incisal margin; and 3, dentine starts to extend onto the lingual surface. Teeth that are entirely worn are referred to as ‘worn’ (Table 1).

Nomenclature of the lingual traits of the central incisor, according to Pilbrow (2006) with minor additions. (a) Ouranopithecus macedoniensis, RPl-293 (size group-A). (b) Ouranopithecus macedoniensis, RPl-230 (size group-B)

| Collection No. | RPl-229 | RPl-230 | RPl-293 | RPl-294 | RPl-103 | RPl-98 | RPl-227 | RPl-94 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Central incisor | LI1 | RI1 | RI1 | LI1 | RI1 | LI1 | RI1 | LI1 | |

| MD | 11.4 | 11.5 | 12.7 | 12.5 | 12.2 | 12.8 | 11.4 | [11] | — |

| LaL | 9.4 | 9.5 | 9.7 | 9.9 | 10.8 | 10.4 | 10.5 | 10.4 | — |

| H | 10.4 | 10.1 | 10.4 | 9.6 | — | — | 6.4 | [7.7] | — |

| % MD/LaL | 122 | 120 | 131 | 126 | — | — | — | — | — |

| % H/MD | 91 | 88 | 82 | 77 | — | — | — | — | — |

| MDR | — | 7.4 | 9.5 | 10.0 | — | — | 9.1 | — | — |

| LaLR | — | 7.5 | 8.9 | 9.2 | — | — | 10.0 | — | — |

| HR | — | — | [26] | — | — | — | — | 19.3 | — |

| H/HR | — | — | 41.5 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| LaLR/MDR | — | 102.0 | 94.0 | 93.0 | — | — | 109.0 | — | — |

| Lateral incisor | RI2 | RI2 | |||||||

| MD | — | — | — | — | 7.0 | — | — | — | 5.7 |

| LaL | — | — | — | — | [7.0] | — | — | — | 6.2 |

| H | — | — | — | — | [7.1] | — | — | — | 4.1 |

| % MD/LaL | — | — | — | — | [101] | — | — | — | — |

| %H/MD | — | — | — | — | [101] | — | — | — | — |

| MDR | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 5.7 |

| LaLR | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 4.7 |

| HR | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| H/HR | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| LaLR/MDR | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 81.3 |

| Wear stage | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | worn | worn | worn |

H, median labial height; HR, median labial height of the root; LaL, labiolingual diameter; LaLR, labiolingual diameter of the root at the cervix; MD, mesiodistal diameter; MDR, mesiodistal diameter of the root at the cervix.

RPl-103 (maxillary fragment with the right I1–I2 and left I1); RPl-98 (right I1); RPl-227 (left I1); RPl-229 (left I1); RPl-230 (right I1); RPl-293 (right I1); RPl-294 (left I1); RPl-94 (right I2), (Figure 1, Table 1). The little-worn central incisors (1st wear stage) include RPl-229, RPl-230, RPl-293, and RPl-294; RPl-103 has quite worn incisors (3rd wear stage) and the other teeth are worn lacking the lingual morphology.

DescriptionThe upper central incisors RPl-293 and RPl-294 have similar size (Table 1) and morphology and probably belong to the same individual as their mesial contact facets fit well each other (Figure 1a, Figure 2a, b). RPl-293 preserves the root except its most apical part, whereas RPl-294 preserves only the cervical half of the root (Figure 2a, b). The occlusal outline of the crown is subelliptical with the labial portion longer than the lingual one. The crown is spatulate, long relative to the LaL diameter (% index MD/LaL >100 and low-crowned relative to the MD diameter (% index H/MD <100) (Table 1). The labial wall of the crown is smooth and mesiodistally convex, but this convexity is restricted to its incisal part. The crown is strongly swollen lingually, forming a basal bulge with no distinct lingual cingulum. There is a pronounced and triangular median lingual pillar that tapers incisally about half of the crown height; it is slightly worn, forming a triangular dentine pit. The median lingual pillar bears an elongated mesial accessory ridge, separated from it by a narrow groove. A well-expressed distal fissure separates the median lingual pillar from the distal marginal ridge (Figure 2a, b, distal view) and by a mesial notch from the mesial marginal ridge (Figure 1a). The mesial and distal foveae, separating the median lingual pillar from the marginal ridges, are nearly identical in size and shape. The almost complete root of RPl-293 is elongated, conical, and bends slightly lingually. The cross-section of the root at the cervix is more or less rounded; the % index LaLR/MDR ranges between 92.5 and 93.6 (Table 1). The RPl-293 and RPl-294 are morphologically and metrically overall similar, but have some minor differences such as the slightly stronger mesial lingual pillar, the slightly larger mesial fovea, and the more worn lingual traits of the latter in comparison with the former.

Upper incisors of Ouranopithecus macedoniensis from the late Vallesian locality Ravin de la Pluie (RPl) of Axios Valley (Macedonia, Greece): (a) right I1, RPl-293; (b) left I1, RPl-294; (c) right I1, RPl-230; (d) left I1, RPl-229; (e) right I1, RPl-98; (f) left I1, RPl-227; (g) right I2, RPl-94; (h) premaxillary fragment with I1–I2 right and I1 left, RPl-103; labial (h1), lingual (h2) view, and lingual morphology of the I2 (h3). From left to right, lingual, labial, mesial, distal and occlusal view.

The other two central incisors, RPl-229 and RPl-230 (Figure 1b, Figure 2c, d), are similarly sized but are smaller than the above-described ones (Table 1); it is quite possible these are antimeres as their morphology and attrition are similar and their contact facets fit well. RPl-230 preserves well the crown, lacking only the mesiolabial enamel peel (Figure 2c, labial view) and the apical half of the root. RPl-229 lacks the distolingual part of the crown and almost the entire root; a small cervical part of the root is only preserved mesiolabially, exposing the pulp canal. The lingual morphology of these central incisors is generally similar to that of RPl-293 and RPl-294 despite minor differences. The most important difference is the presence of a second lingual pillar, situated mesially to the median one (mesial lingual pillar). The median and mesial lingual pillars of RPl-229 and RPl-230 are equally sized; the mesial one is stronger and longer than that in RPl-293 and RPl-294, separated well from the median one by a large and deep groove. Both pillars are more worn than those of RPl-293 and RPl-294, presenting triangular dentine pits. The distal marginal ridge is thinner and less convex distally than that of RPl-293 and RPl-294. The mesial fovea of RPl-229 is narrower and deeper than that of RPl-230.

The maxillary fragment RPl-103 preserves poorly the most anterior part of the premaxilla with the incisors. The central incisors are quite worn (3rd wear stage) and have lost most of their lingual morphology. The I1 is similar in size to RPl-293 and RPl-294 (Table 1; Fig. 4a); a pronounced basal bulge and a median lingual pillar can be distinguished better in the left I1. The lateral incisor preserves the lingual incisal part of the crown; it is peg-shaped, subelliptical in occlusal view, and markedly smaller than the central incisor (Figure 2h). The labial wall is smooth and strongly convex mesiodistally. Two small lingual ridges run from the incisal margin towards the base of the crown (Figure 2h3). The thick mesial and distal marginal ridges are a continuation of the incisal margin. The central incisors RPl-98 and RPl-227 (Figure 2e, f) are heavily worn and the crown is a large dentine pit surrounded by enamel; both preserve the root. The occlusal outline of the crown is suboval. The root is like that of the above-described specimens. The lateral incisor RPl-94 (Figure 1g) preserves well the crown and the most cervical part of the root. The crown is heavily worn, showing a subtriangular occlusal outline. The root is flattened mesiodistally, having an elliptical cross-section.

As the morphology of the post-canine teeth has been traditionally used for the taxonomy and phylogeny of the Miocene hominoids, the role of the incisors has long remained limited. Since the beginning of the 1990s, some scientists have started to use the incisor’s lingual morphology to distinguish certain hominoid samples (e.g. Begun et al., 1990; Begun, 1992; Andrews et al., 1996; Ward et al., 1999), although they were some doubts regarding their taxonomic and/or phylogenetic significance (Harrison, 1991; Ribot et al., 1996). On the other hand the incisor’s lingual morphology in the modern great apes shows great variation (Kelley et al., 1995; Benefit and McCrossin, 2000; Pilbrow, 2006). According to the last author the incisors of the extant great apes (gorillas, chimpanzees, orang-utans) have a high variation in their lingual morphology within the species and local populations, though it is possible in some populations to separate statistically species or subspecies based on the frequency of the lingual incisor traits (Pilbrow, 2006). In some recent publications, the incisor’s lingual morphology has been used for taxonomic separation of some Miocene hominoid samples (e.g. Kelley et al., 2008; Alba et al., 2012; Pérez de los Ríos et al., 2012, 2013), but these studies did not rule out the possibility of sampling bias (as the fossil samples are small) or the presence of variation such as that observed in extant taxa (Alba et al., 2012; Pérez de los Ríos et al., 2012, 2013).

Keeping in mind all the above, we shall try to compare the Ouranopithecus upper incisor’s lingual morphology with those of some Miocene hominoids. The comparison is restricted to the known material of each taxon and cannot be generalized, as the known incisor samples for most fossil hominoids are very poor, including a single or a few specimens, and their morphological variation is unknown. As the incisor’s lingual morphology of the modern hominoids is variable (Pilbrow, 2006), the comparison with those of O. macedoniensis cannot give clear results; moreover, if we accept a variation in Ouranopithecus incisors, similar to that of the modern hominoids, then the comparison will provide more questionable results. Based on the comparison with the small samples of the modern hominoid incisors we have seen, however, we can say that the upper incisors of O. macedoniensis have generally more similar lingual morphology to those of Gorilla and Pan than to those of Pongo. The upper incisors of the last taxon, with strongly wrinkled enamel in their lingual surface and basal bulge, are well distinguished from those of O. macedoniensis (Figure 3).

Upper incisors of the modern great apes, Gorilla, Pan, and Pongo (1st and 2nd wear stage).

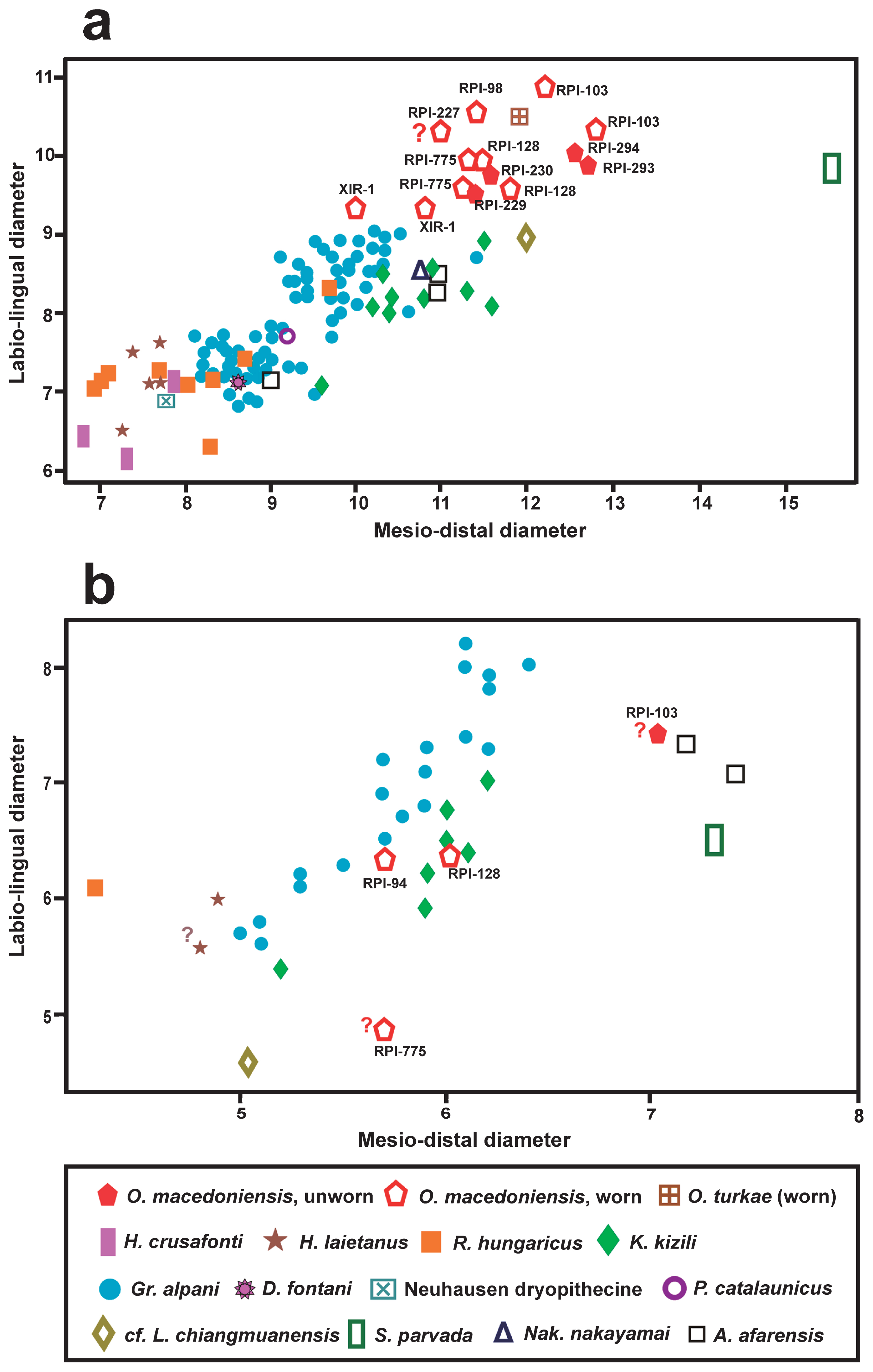

Scatter diagram (MD/LaL) comparing the upper central (a) and the lateral (b) incisors of Ouranopithecus macedoniensis with those of other hominoids. Question mark indicates estimated measurements. Figures 2 and 5 of Kelley et al. (2008) were used as the basis for these diagrams. Data sources: Alba et al. (2012), Chaimanee et al. (2003), Güleç et al. (2007), Kelley et al. (1995), Kimbel et al. (1982), Kordos and Begun (2001), Kunimatsu et al. (2007), Pérez de los Ríos et al. (2012, 2013), and Pickford (2012).

Several Miocene hominoids are known from Turkey and the taxon closer in age to the studied one is Ouranopithecus turkae, known from the late Miocene locality Çorakyerler (Güleç et al., 2007). The I1 of this species has similar lingual morphology and size to that of O. macedoniensis, especially with RPl-293 and RPl-294 (Figure 4a, Figure 5). Two other hominoids, Kenyapithecus kizili and Griphopithecus alpani, are known from the middle Miocene locality Paşalar with a large number of upper incisors in the collection, especially from the second taxon (Kelley et al., 2008: fig. 1). The I1 of K. kizili differs from that of O. macedoniensis in displaying a triangular lingual outline with parallel mesial and distal sides over the incisal half of the crown, a strongly projected lingually basal bulge without observed median lingual pillar, a thick (hypertrophied) mesial and lingual marginal ridge, a less convex distal marginal ridge, smaller mesial and distal foveae, and smaller size (Figure 4a). The I2 of the same species (Kelley et al., 2008: fig. 4) is separated from that of Ouranopithecus in exhibiting a rhomboid lingual outline, more accessory ridges on the lingual surface, and probably slightly smaller size, as it is smaller than the less worn I2 of Ouranopithecus (RPl-103) (Figure 4b). The I1 of Griphopithecus alpani, the second hominoid from Paşalar (Kelley et al., 2008: fig. 1), has a rhomboid lingual outline, a pronounced median lingual pillar, a thicker and less convex distal marginal ridge, and smaller size than that of Ouranopithecus (Figure 4a). The I2 of G. alpani (Kelley et al., 2008: fig. 4) has similar morphology to that of Ouranopithecus but is slightly shorter (Figure 4b).

Lingual morphology of the upper central incisor of Ouranopithecus and Nakalipithecus. (a) O. turkae, Çorakyerler, Turkey, 18ÇO 2100 (photo kindly provided by A. Sevim Erol); (b, c) O. macedoniensis, Ravin de la Pluie, Greece, RPl-293 and RPl-230, respectively; (d) Nakalipithecus nakayamai, Nakali, Kenya, KNMNA47592 (photo kindly provided by Y. Kunimatsu); (e) Australopithecus afarensis, Hadar-Afar, Ethiopia, A.L.200-1a (cast).

Rudapithecus hungaricus is a late Miocene hominoid found in the locality Rudabánya, Hungary (Begun and Kordos, 1993; Kordos and Begun, 2001). The I1 of this taxon has a higher crown relative to MD, a shorter MD diameter relative to LaL (Table 2), and a more prominent basal bulge than that of Ouranopithecus. The I2 of R. hungaricus has high crown and triangular lingual outline (Kordos and Begun, 2001: fig. 1), differing from that of Ouranopithecus in having a mesiodistally shorter crown relative to LaL (Table 3) and an angular incisal margin.

| Species | Collection No. | MDI1 | LaLI1 | HI1 | %MD/LaLI1 | %HI1/MD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ouranopithecus macedoniensis | RPl-293 | 12.7 | 9.7 | 10.4 | 131 | 82 |

| RPl-294 | 12.5 | 9.9 | 9.6 | 126 | 77 | |

| RPl-229 | 11.4 | 9.4 | 10.4 | 122 | 91 | |

| RPl-230 | 11.5 | 9.5 | 10.1 | 120 | 88 | |

| RPl-103 | 12.2 | 10.8 | — | 113 | — | |

| 12.8 | 10.4 | — | 123 | — | ||

| RPl-775 | 11.5 | 9.9 | — | 116 | — | |

| 11.3 | 9.5 | — | 119 | — | ||

| Ouranopithecus turkae | CO-205 | 11.9 | 10.5 | — | 113 | — |

| Hispanopithecus crusafonti | IPS 1807 | 7.6 | 6.2 | 11.4 | 123 | 150 |

| IPS 1808 | 7.7 | 6.2 | 10.7 | 124 | 139 | |

| IPS 1809 | 7.8 | 6.7 | 12.5 | 116 | 160 | |

| Hispanopithecus laietanus | IPS 61398 | 7.4 | 7.5 | — | 99 | |

| Rudapithecus hungaricus | RUD 121 | 6.9 | 7.0 | 11.1 | 99 | 161 |

| RUD 199 | 6.9 | 7.0 | 10.8 | 99 | 157 | |

| Dryopithecus fontani | NMB G.a.9 | 8.6 | 7.1 | 11.3 | 121 | 131 |

| Dryopithecine Neuhausen | SMNS 47444 | 7.8 | 6.9 | 11.0 | 113 | 141 |

| Pierolapithecus catalaunicus | IPS-21350.1 | 7.6 | 9.0 | — | 84 | — |

| Nakalipithecus nakayami | KNM-NA47592 | 10.8 | 8.6 | 11.8 | 126 | 109 |

| cf. Lufengpithecus chiangmuanensis | TF 6168 | 12.0 | 8.9 | — | 135 | — |

| Sivapithecus parvada | GSP 46460 | 15.5 | 9.8 | — | 158 | — |

| Australopithecus afarensis | A.L. 200-1a | 10.9 | 8.5 | — | 128 | — |

| 10.9 | 8.3 | — | 131 | — | ||

| A.L. 333x-4 | 10.8 | 8.6 | — | 126 | — |

| Species | Collection No. | MD | LaL | H | %MD/LaL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ouranopithecus macedoniensis | RPl-103 | 7.0 | [7.0] | [7.1] | [101] |

| RPl-94 | 5.7 | 6.2 | 4.1 | 93 | |

| RPl-128 | 6.0 | 6.4 | 4.7 | 94 | |

| RPl-775 | ?4.8 | ?5.7 | — | ?84 | |

| Ouranopithecus turkae | CO-205 | 6.3 | 7.2 | — | 88 |

| Hispanopithecus laietanus | IPS 58331 | 4.8 | [5.6] | — | [86] |

| IPS 58333 | 4.9 | 6.0 | — | 82 | |

| Rudapithecus hungaricus | RUD-197 | 4.3 | 6.1 | 70 | |

| Sivapithecus parvada | GSP 46460 | 7.3 | 6.6 | — | 111 |

| cf. Lufengpithecus chiangmuanensis | TF 6173 | 5.1 | 4.6 | — | 110 |

| Austarlopithecus afarensis | A.L. 200-1a | 7.4 | 7.0 | — | 106 |

| 7.2 | 7.3 | — | 99 |

The Spanish record of Miocene hominoids is rich, including several taxa. The best-known genus is Hispanopithecus, known with two taxa: H. crusafonti and H. laietanus. The I1 of H. crusafonti from the late Miocene of Vallès Penedès (Begun, 1992: fig. 8; Alba et al., 2012: fig. 4) differs from that of O. macedoniensis in showing a higher crown relative to MD (Table 2), a vertical groove in the mesial half of the labial surface, a triangular lingual outline, a basal bulge separated from the mesial and distal marginal ridges by deep mesial and distal vertical fissures, a strong median lingual pillar, no mesial lingual pillar, a thick mesial marginal ridge, a less convex distal marginal ridge, and remarkably smaller size (Figure 4a). The I1 of H. laietanus differs from that of Ouranopithecus in displaying a mesiodistally shorter crown relative to the LaL (Table 2), a vertical groove in the mesial half of the labial surface, absence of median lingual pillar, a less convex distal marginal ridge (Alba et al., 2012: fig. 3G; Pérez de los Ríos et al., 2013: fig. 4F–J), and smaller size (Figure 4a). The I2 of H. laietanus has variable lingual morphology (Alba et al., 2012: fig. 4L–O) and differs from that of O. macedonienesis in having smaller size (Figure 4b) and a mesiodistally shorter crown relative to LaL (Table 3); the little-worn IPS-58333 of H. laietanus is distinguished from that of O. macedoniensis in displaying wrinkled enamel on the lingual surface.

One I1 (IPS-21350, holotype) of Pierolapithecus catalaunicus was described from the middle Miocene site Barranc de Can Vila (Pérez de los Ríos, 2012: fig. 1A–E). The more pronounced basal bulge, the single median lingual pillar, the less convex distal marginal ridge, the mesiodistally shorter crown relative to LaL (Table 2), and the smaller size (Figure 4a) distinguish it from O. macedoniensis.

The single known I1 of Dryopithecus fontani from the middle Miocene locality La Grive, France, was recently redescribed and revised (Pérez de los Ríos et al., 2013: fig. 1A–E). Besides its markedly smaller size (Figure 4a) it differs from the central incisor of Ouranopithecus in displaying a large vertical groove on the mesial half of the labial crown surface, a higher crown relative to MD (Table 2), a strong median lingual pillar, no mesial lingual pillar, and a less convex distal marginal ridge. Among the dryopithecine material from the middle Miocene locality Neuhausen (Germany) there is a moderately worn I1 (Pickford, 2012: fig. 5). It differs from the Ouranopithecus central incisor in exhibiting a vertical groove in the mesial half of the labial crown surface, a higher crown relative to MD, a mesiodistally shorter crown relative to LaL (Table 2), a triangular lingual outline, a more lingually projected basal bulge, wrinkled enamel on the basal bulge (Pickford, 2012: fig. 5), and remarkably smaller size (Figure 4a).

The central incisor of the Chinese late Miocene hominoid Lufengpithecus lufengensis differs from that of Ouranopithecus in having a more rounded occlusal outline of the crown (the % index MD/LaL >90 and in one case equals 100), strongly wrinkled enamel on the basal bulge and lingual surface, a thicker mesial marginal ridge and a less convex distal marginal ridge (Xu and Lu, 2008: figs. 2.13, 4.1, 4.2). The lateral incisor of L. lufengensis differs from that of Ouranopithecus in showing an angular incisal margin, and weaker mesial and distal marginal ridges. A single I1 (TF-6168) of the hominoid cf. L. chiangmuanensis (Chaimanee et al., 2003: fig. 3a) differs from that of Ouranopithecus in displaying a basal bulge that is restricted to the cervical part of the crown, wrinkled enamel on the basal bulge and lingual surface, smaller mesial and distal foveae, and a less convex distal marginal ridge. The smaller size (Figure 4b), the mesiodistally shorter crown relative to the LaL (Table 3), and the presence of lingual cingulum (Chaimanne et al., 2003: fig. 3j) separate the I2 of cf. L. chiangmuanensis from that of O. macedoniensis.

A single I1 (GSP 46460) of Sivapithecus parvada from the late Miocene of Siwaliks, Pakistan differs from that of O. macedoniensis in having a hexagonal outline in lingual and labial aspect, a mesiodistally longer crown relative to LaL (Table 2), entirely wrinkled enamel on the basal bulge, numerous faint wrinkles on the lingual surface (Kelley, 1988: fig. 2), and a larger size (Figure 4a). The mesiodistally shorter crown relative to LaL (Table 3) and the angular incisal margin of the S. parvada I2 (Kelley et al., 1995: fig. 2) distinguish it from that of Ouranopithecus. Two other unworn upper central incisors of Sivapithecus from Siwaliks (GSP 6999 and YPM 16919) were described and figured by Kelley (1988: fig. 2). They differ from Ouranopithecus I1 in the above-mentioned features, but have smaller size; the dimensions of the unworn I1 GSP 6999 are 10.3 × 7.6 mm (Pilbeam, 1969).

One isolated and little-worn upper central incisor is known from the late Miocene hominoid Nakalipithecus nakayamai from Nakali, Kenya (Figure 5d), described by Kunimatsu et al. (2007: fig. 3c). The subelliptical lingual outline, the mesiodistally short crown relative to LaL (Table 2), the presence of a weak lingual pillar, the few accessory lingual ridges, and the strongly curved distal marginal ridge of its I1 agree with the morphology of RPl-293 and RPl-294 (Figure 5b, d). However, it differs from Ouranopithecus I1 in having slightly smaller size (Figure 4a), and a lingual cingulum continuous with the mesial and distal marginal ridges (Kunimatsu et al., 2007), a trait that is absent in O. macedoniensis.

The described incisors are compared with the littleworn incisors preserved in the maxilla A.L.200-1a of Australopithecus afarensis (Kimbel et al., 1982: fig. 4) [comparison with a cast housed in the Institut International de Paléoprimatologie, Paléontologie Humaine: Evolution et Paléoenvironnements, Université de Poitiers, France (Figure 5e)]. Apart from its smaller size, the A. afarensis I1 differs from Ouranopithecus in having a triangular lingual outline versus subelliptical in Ouranopithecus, a strong and lingually projected basal bulge, a strong median lingual pillar, a relatively larger mesial fovea, and no accessory lingual ridges. The I2 of A. afarensis is completely different from that of Ouranopithecus in showing a larger size relative to the I1, a triangular lingual outline, and a mesiodistally longer crown relative to LaL (Table 3).

The old collection of Ouranopithecus from the various localities lacks unworn or little-worn incisors, a fact that prevents a direct morphological comparison with the described new incisors. Hence, the comparison is limited to a metrical one, indicating that all newly described incisors are within the variation for O. macedoniensis (Figure 4). The metrical similarity and the monospecific character of the RPl hominoid sample (Koufos et al., 2016b and references therein) indicate that the described new incisors belong to O. macedoniensis.

The lingual morphology of Ouranopithecus central incisors is generally consistent. Small differences among the described specimens, such as the presence of a mesial lingual pillar in the small-sized I1, the thicker and more convex distal marginal ridge, and the wider distal fovea of RPl-293 and RPl-294 in comparison to RPl-229 and RPl-230, can be considered intraspecific variation and cannot allow the separation of different morphs. Despite the morphological resemblance of the described central incisors, their dimensions allow them to be divided into two groups: the large-sized group-A (RPL-293, RPl-294) and the small-sized group-B (RPl-229, RPl-230) (Figure 4a). The size difference could be related to the attrition, the gradual increase of which affects the dental dimensions. However, the role of attrition is limited, as the compared teeth are more or less at the same wear stage. In order to certify this size difference, the dental dimensions of the I1 were measured in a standard point, the cervix, and plotted in a scatter diagram (Figure 6). The separation of the RPl sample in two size groups is clear, confirming that the role of attrition is limited. The attribution of the other known Ouranopithecus central incisors from RPl to these size groups is based on their size as they are worn and their lingual morphology has disappeared. Based on their dimensions at the cervix (Figure 6), the specimens RPl-98, RPl-103, RPl-128 and RPl-775 match with RPl-294 and RPl-294 and can be included in the large-sized group-A. The small-sized group-B includes only the specimens RPl-229 and RPl-230.

Scatter diagram (MD/LaL at the cervix) comparing the upper central incisor of Ouranopithecus macedoniensis from Ravin de la Pluie, RPl. Specimens marked with an asterisk are confidently assigned as male (associated with canines).

The size difference in the dentition of O. macedoniensis has long been recognized and was ascribed to sexual dimorphism. The species is considered as one of the most dimorphic hominoids, comparable to the extinct Lufengpithecus lufengensis and the extant Pongo (see Koufos et al., 2016a and references therein). Therefore the observed size differences of the upper central incisors can be explained by this sexual dimorphism. Consequently, the size group-A corresponds to male and the group-B to female individuals. Such size differences are also observed in both Paşalar hominoids, whose incisors are separated in two size groups corresponding to males and females (Kelley et al., 2008). However, the absence of specimens with unworn incisors in situ associated with canines cannot allow us to confirm this hypothesis for now.

The limited number of incisors in the RPl sample of O. macedoniensis and of the other known Miocene hominoids, combined with the possible intraspecific variation in their lingual morphology, as in the modern hominoids, does not allow confident comparisons and results for their systematic and/or phylogenetic relationships.

We are grateful to a great number of colleagues and students who excavated with us in the field, since the 1970s, and to those who helped in the preparation of the fossils. Thanks to Y. Kunimatsu and A. Sevim Erol for providing us with photos from their material and the former for also providing us with the Nakali I1 measurements. We are also thank D. Johanson for providing us the cast of A. afarensis. G.D.K. thanks O. Kullmer, I. Ruf, and K. Krohmann for giving him access to the collection of the modern primates and helped him at Senckenberg Forschungsinstitut und Naturmuseum Frankfurt, Germany. We thank K. Harvati for the comments and linguistic improvement of the text, as well as to K. Vasileiadou for linguistic diligence with the text. We also thank two anonymous reviewers and the associate editor R.T. Kono for their constructive comments and suggestions, which improved the manuscripts significantly. Thanks are also due to the editor M. Nakatsukasa and associate editor R.T. Kono for their help and rapid reviewing process.