2021 Volume 129 Issue 1 Pages 35-44

2021 Volume 129 Issue 1 Pages 35-44

Kim Busik’s Samguk Sagi 三国史記, History of the Three Kingdoms, dating from 1145 A.D., is renowned for including Japanese toponyms in the Korean peninsula and the north of Yalujiang district (modern Liaoning and Jilin Provinces). Kim’s work recorded the older, archaic toponyms before they were converted into sinicized (i.e. expressed with Chinese words) place names with two Chinese characters in 757 A.D. by the order of King Kyeongdeok. This paper maps specific words included in the place names of 783 locations for which the corresponding present places are evident. The following were words examined: (1) ‘river’ and its related words; (2) ‘valley’; (3) ‘mountain’ and ‘ridge’; and (4) ‘city’ and ‘burg’. Japonic-sourced toponyms are typically distributed in the central and northern areas of the Yalu River, primarily in the district of Koguryŏ; however, they go beyond these regions. The use of Chinese loanwords is noted in the southern area, where determining which language was spoken is difficult. In a town near Seoul, the stem of the toponym belongs to the Korean language, whereas the unit word belongs to the Japonic language. This usage may be attributed to bilingualism, whereby Korean-speaking inhabitants used their own language for the stem of the place name. Mongolic and/or Tungusic loanwords are also found. In some cases, determining the language origin of the current toponyms is difficult. Therefore, the minute geographical distribution of the origin languages is displayed word by word. These toponyms reflect the traces of indigenous languages and reveal that Japonic-speaking people still dwelled in the central area of the peninsula and in the northern area of the Yalu River at that period.

This paper aims to determine the geographical distribution and interrelationship of certain human groups in the Korean peninsula around the first half of the first millennium A.D., using the evidence of old toponyms. As previously argued, including by Whitman (2011), Unger (2014), Miyamoto (2017), and others, the existence of Japonic-origin toponyms in the peninsula reveals the trace and migration route of the ancestors of Yaponesians.

Since Shiratori (1895–1896) pointed out that a series of old toponyms in Koguryo in the Samguk Sagi could be interpreted in relation to Japanese words, much research has been undertaken on these toponyms by Japanese, Korean, and Western scholars. For example, Lee (1968) and Beckwith (2007) state that the Koguryo language belongs to the Japonic family. Kono (1993), however, considers that these Japonic-related toponyms were left by the Ye 濊 people who dwelled in the mid-eastern part of the peninsula (roughly, modern Gangwon Province). His claim relies on the fact that Japanese people were called ‘Ye’ in Middle Korean during the 15th and 16th centuries. As shown in the maps below, Japonic toponyms are widely distributed not only in the territory of Ye, but also in the former territory of Hanseong Baekje before its conquest by Koguryo. This conundrum will be discussed later.

The Samguk Sagi 三国史記, History of the Three Kingdoms, the oldest historical record of Korea, was compiled by Kim Busik and others in 1145 A.D. Volumes 34–37 include toponyms from 1199 places in the territory of Unified Silla. Volume 34 is devoted to preunification Silla, Volume 35 to the former Koguryo and Volume 36 to the former Baekje. Volume 37 is divided into three parts: (1) a rather precise comparison of old and new toponyms in Koguryo and Baegje; (2) a collection of toponyms from the whole book which could not be identified with later places; (3) a list originating from a report to the Emperor of the Tang Dynasty by General Li Ji in 669 A.D. after victory in the war against Koguryo, in which occupation status was described city by city in the north of Yalujiang district (modern Liaoning and Jilin Provinces). King Kyeongdeok ordered older, barbarian toponyms to be changed into sinicized ones with two Chinese characters in 757 A.D. Comparisons of the two forms are particularly common in Volume 37.

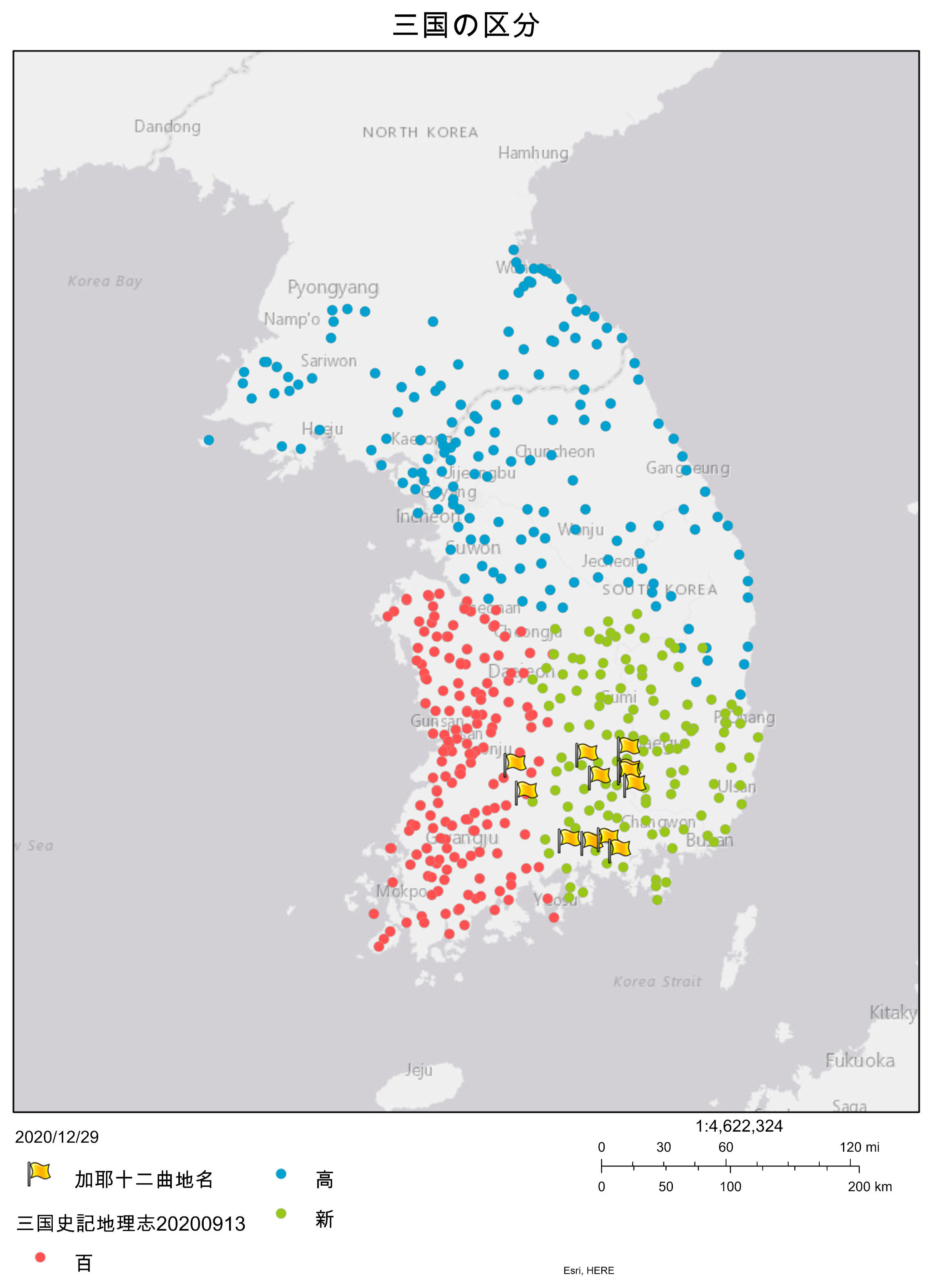

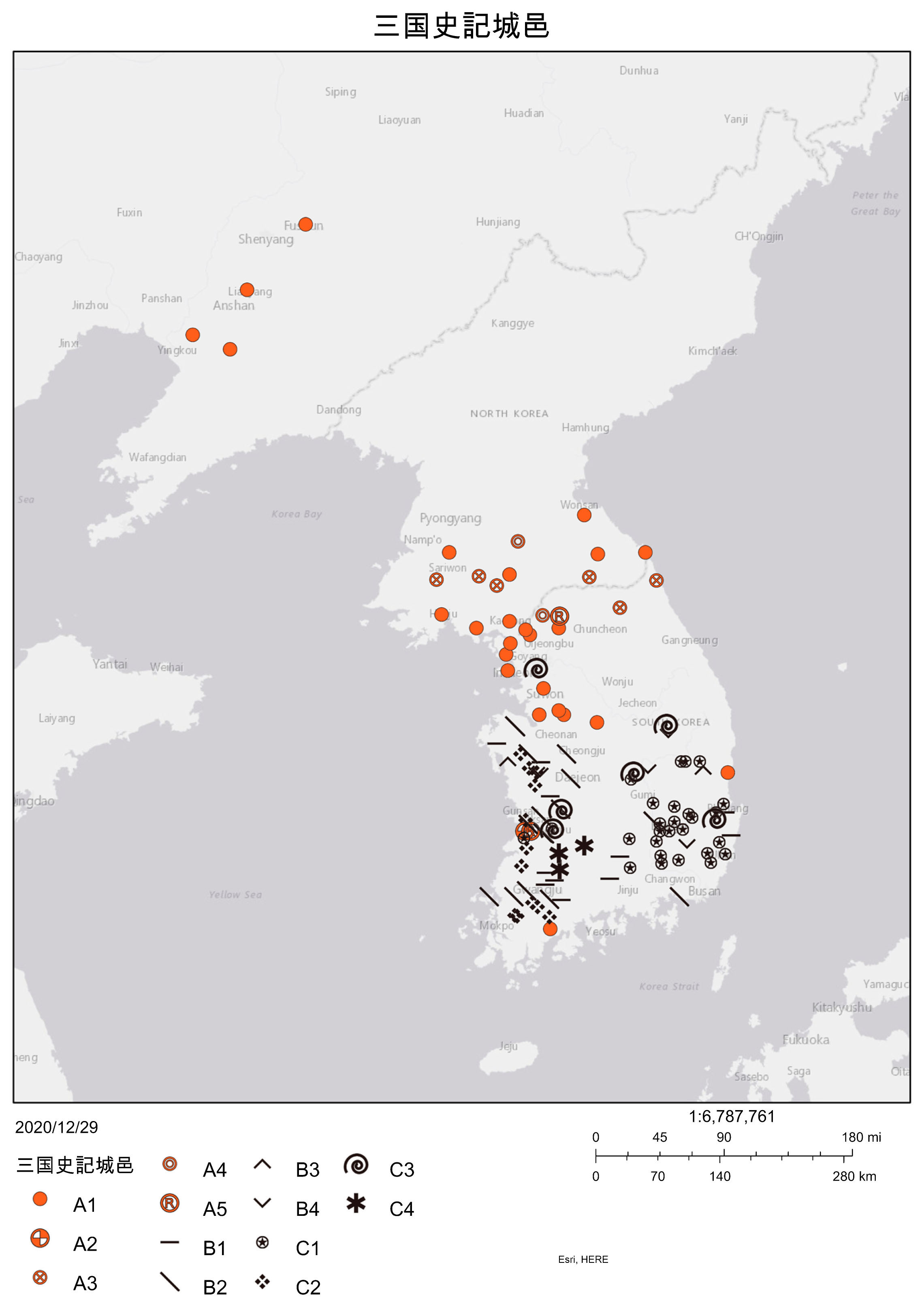

The basic data for this study are 783 locations for which Inoue (1986) identified corresponding modern places. Figure 1 shows the towns of Silla (green), Koguryo (blue), and Baekje (red), respectively. A red dot appears between Koguryo and Silla, but this place occupies the last position in the Baekje volume, suggesting the original compilers were aware of its irregularity. The location is identified on the basis of the original description. The places indicated by yellow flags are the 12 city-states of Gaya given in Tanaka (1990).

Locations examined in this study

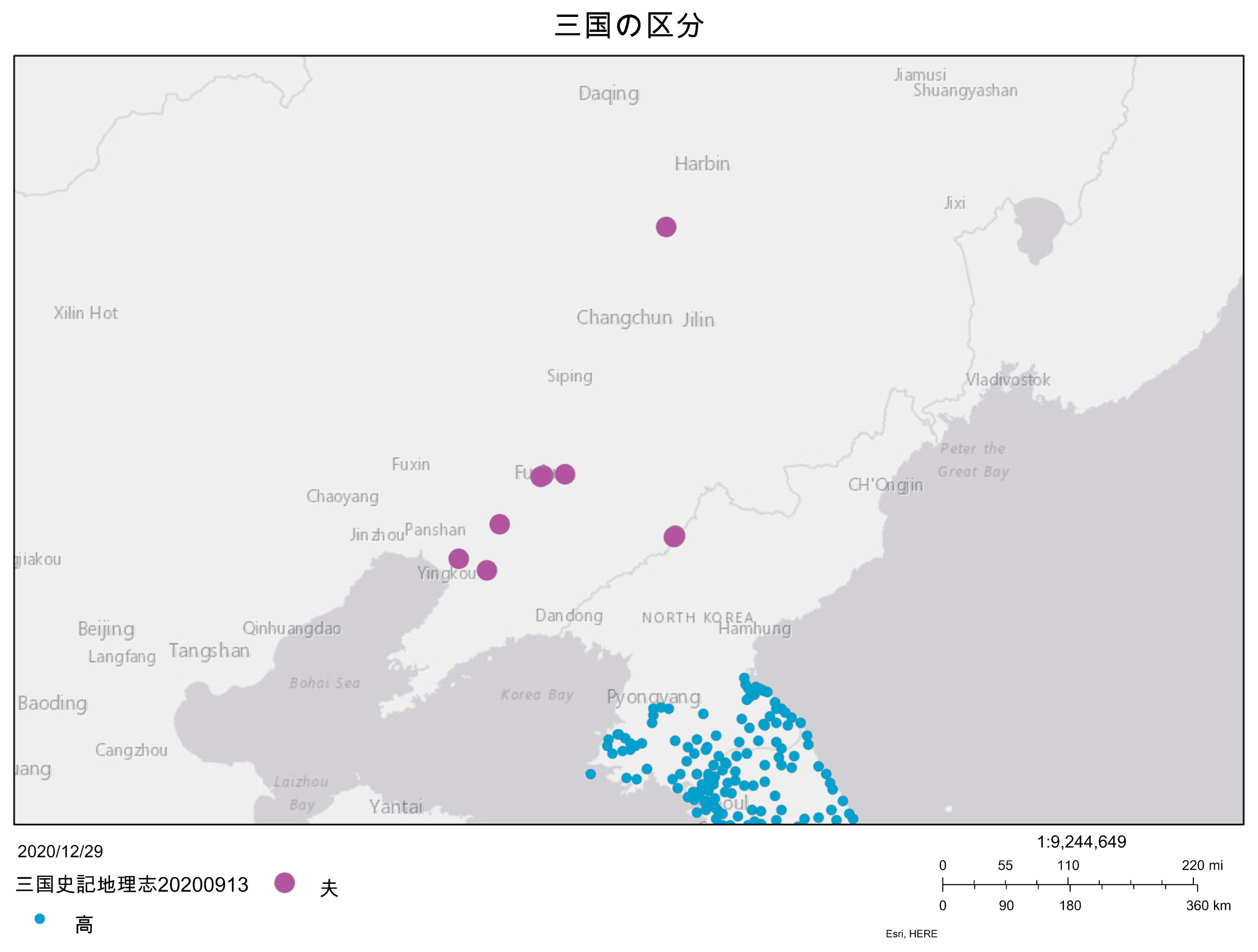

Figure 2 shows some exceptional cities north of the Yalu River whose specific locations are known. Although it is difficult to ascertain exactly which modern places correspond to the places identified in the Samguk Sagi in this area, several Japonic-related toponyms were also found here. They are as follows: ‘居尸𡊠’: ‘心岳城’, ‘乃勿忽’: ‘鈆城’, ‘蕪子忽’: ‘節城’, ‘骨尸𡊠’: ‘朽岳城’.

Cities north of the Yalu River

Inoue (1962: 47) introduced his contribution with the lines “Analyzing the toponyms seen in the volumes on geography of the Samguk Sagi, the distribution of the Ye-maek 濊 貊tribe and the Han 韓 tribe will be clarified, and areal characteristics of these tribes also can be detected.” He went on to mention that Mishina Shoei had already written a paper on the subject, although it was unfortunately lost during World War II. Inoue (1962) minutely traced the geographical distribution of the terminal elements of the toponyms in the Samguk Sagi, drawing a precise map in which all of these elements appeared. The present paper continues this endeavor by mapping individual features separately with special attention to the origin languages. The maps below were drawn with ArcGIS online.

The first point of discussion concerns words or morphemes (i.e. elements that cannot appear independently) written with the Chinese characters ‘買’ and ‘勿’. In many, although not all cases, these relate to ‘water’.

There are 34 examples of ‘買’ in Volumes 34–37, of which 11 cases are seen in both Volumes 35 and 37. These examples are classified into five types (A–E) based on their meanings. Those in type A have the meaning ‘water’ in common, and the subtypes A1 (river), A2 (a well), A3 (water), and A4 (a pond) are identified according to minor semantic differences. Hereafter, letters (A, B, C, etc.) are used for the different words, and numbers (1, 2, 3, etc.) are used to denote the subtypes. A unified color system is utilized throughout: red stands for Japonic origin, blue for Koreanic, green for Sinitic, orange for Tungusic and/or Mongolic, and black for items where two or more possible origins exist.

Type A1, represented by a red horizontal bar in Figure 3, ends with ‘買’ in old toponyms and its corresponding revised form as of 757 A.D. was ‘川’. In figure legends, if that Chinese character appears in the final position, a dash is added before it. If it appears in the initial position, a dash is added after it. If it appears in both positions, no dash is added. ‘買’ represents a sound like *MI (‘*’ is added before a reconstructed form), while ‘川’ represents the meaning ‘river’. Since it remains premature to reconstruct the exact sounds of each Chinese character, the phonetic notation is indicated by the upper case as in *MI, where *M and *I stand for the approximate sounds. Parentheses are added if a sound is able to disappear. In this case, *M can safely be treated as [m], while *I may be [i, e, ɛ, a] or the other vowels. This corresponds with the Old Japanese mi ‘water’. River is expressed as kapa in Old Japanese, and mi became a bound morpheme which appears only in compound words. In this case, *MI serving as ‘river’ may be an archaism. Type A2, represented with a red oblique line, ends with ‘買’ in old toponyms and the revised form is ‘井’, meaning ‘a well’. Type A3, represented with a red rhombus, starts with ‘買’ in old toponyms and the revised form is ‘水’, meaning ‘water’. Type A4, represented with a red asterisk, ends with ‘米’, whose sound is similar to ‘買’ in old toponyms and whose revised form is ‘池’, meaning ‘a pond’. All four types have the meaning ‘water’.

Geographical distribution of ‘買’ and ‘-勿’.

Some explanation is necessary for two toponyms. Firstly, for Haeju near present-day Kaesong, the old toponym is ‘內米忽’ *NAMIKO(L) and the revised toponyms are ‘池城’ (pond-burg), ‘長池’ (long pond) or ‘瀑池’ (falling pond, waterfall). Murayama (1961) says: “內米 naimi maybe has the meaning of ‘a wallowing lake’ or ‘sea’ at the same time.” However, nami means ‘wave’ in Old Japanese, as in modern Japanese. The semantic distance between ‘wave’ and ‘pond, lake, or sea’ is rather large. It is noteworthy that a corresponding toponym exists meaning ‘long pond’, raising the possibility that *NA-MI stands for ‘a long water’ corresponding to Old Japanese naga-mi (‘long water’). There is a long bay in Haeju, which could be the etymology (i.e. the origin of the name) for the town. As seen in Tanaka (1990), there is a notably strong tendency in Sino-Xenic throughout the Three Kingdoms, including Gaya, to drop the last elements of a syllable (i.e. a basic sound unit that consists of a consonant + medial vowel + principal vowel + consonant/final vowel in Chinese, as seen in the example nuɑi below), as well as lenition (i.e. weakening of the sounds), and omitting round vowel elements. In this case, the Middle Chinese ‘內’ *nuɑi appears as *NA, omitting -u- and -i, respectively.

Secondly, for ‘仁川’, present-day Incheon, there are two old forms ‘買召忽’ and ‘彌鄒忽’, while the new one is ‘邵城’, which is unrelated to water. This intermediate form may have been derived from ‘買召忽’, in which ‘召’ has the same phonetic element as ‘邵’. Although the toponym of the later period includes ‘川’, meaning ‘river’, its reliability is not as high as the equation made in the Samguk Sagi. Nonetheless, a legend exists that King Biryu, the second son of Jumong, dwelled in ‘弥鄒忽’, but as it was humid there and the water was salty, life was hard. Since this story is related to water, as ‘弥’ is the simplified form of ‘彌’, it can be interpreted as corresponding with the Old Japanese midu (‘water’). This toponym occurs in the Gwanggaeto Stele, thus dating to at least the early fifth century A.D.

Type B, represented with a red whorl, includes ‘買’ in old toponyms and its corresponding revised form is ‘善’ (‘virtue’). It may correspond to Old Japanese mi meaning ‘divine, honorable, sacred’. Type C, represented with a red inverse baby-like symbol, is seen in one location, presentday Wonsan: old toponym ‘買尸達’: new toponym ‘䔉山’. As discussed below, ‘達’ means ‘山’ (‘mountain’), hence ‘買尸’ means ‘䔉’ (‘garlic’). This corresponds with Old Japanese mira, the modern form of which is nira, meaning ‘Chinese chive’.

As types A–C may be interpreted in Japonic terms, all are represented with red symbols. Ordinarily, types B and C should be excluded from the map, since their meanings are different from types A1–A4. However, the other Japonic-related toponyms are distributed in exactly the same area as types A1–C. It is also noteworthy the same Chinese character is used to denote three different words in Japonic. Accordingly, all were included in Figure 3.

Type D, represented with a black wave-like symbol, ends with ‘勿’ in old toponyms and its corresponding revised form is ‘水’ (literally ‘water’, but also denoting ‘river’ in early Chinese). This type is seen in the far south as well as near Kaeseong. If ‘勿’ is pronounced as *MUL, it should relate to the Korean word meaning ‘water’. However, there is another possibility that its reading is *MI without rounding medial vowel and -L ending. Compare the Koguryo name ‘泉蓋蘇文’ in the Samguk Sagi, spelled as ‘伊梨柯須 彌’ in the Nihon Shoki, where the character ‘文’ is read as ‘彌’ *MI, omitting the round medial vowel and final consonant-n. Then a possible connection to Japonic emerges. In such a vague case, a black color is used to denote two possible etymologies.

Another location is shown with a dark blue vertical bar near Wonju, which is Hoengseong in present-day Kangwon. The old toponym is ‘於斯買’ and its revised form is ‘橫川’. ‘買’ came from Japonic, but ‘於斯’ came from the Korean *əs, ‘horizontal’ (Lee, 1968). This toponym consists of a Korean-origin stem plus a Japonic-origin unit term. It is often seen that unit terms such as ‘village’, ‘town’, ‘county’, etc., are derived from another prestigious language (i.e. Classical Greek and Latin in Europe or Chinese in East Asia). For example, son (‘village’), shi (‘city’), gun (‘county’), ken (‘prefecture’), and koku (‘country’) in modern Japanese are Chinese loanwords. Moreover, citing an example from the Samguk Sagi itself, ‘忽’ (‘burg’) is used as the unit term in ‘內米忽’ *NAMIKO(L) mentioned above. As will be discussed below, ‘忽’ originated either from Mongolic or Tungusic, which was dominant in northern China during that period. It is thus likely that Japonic was more dominant than Korean in this town.

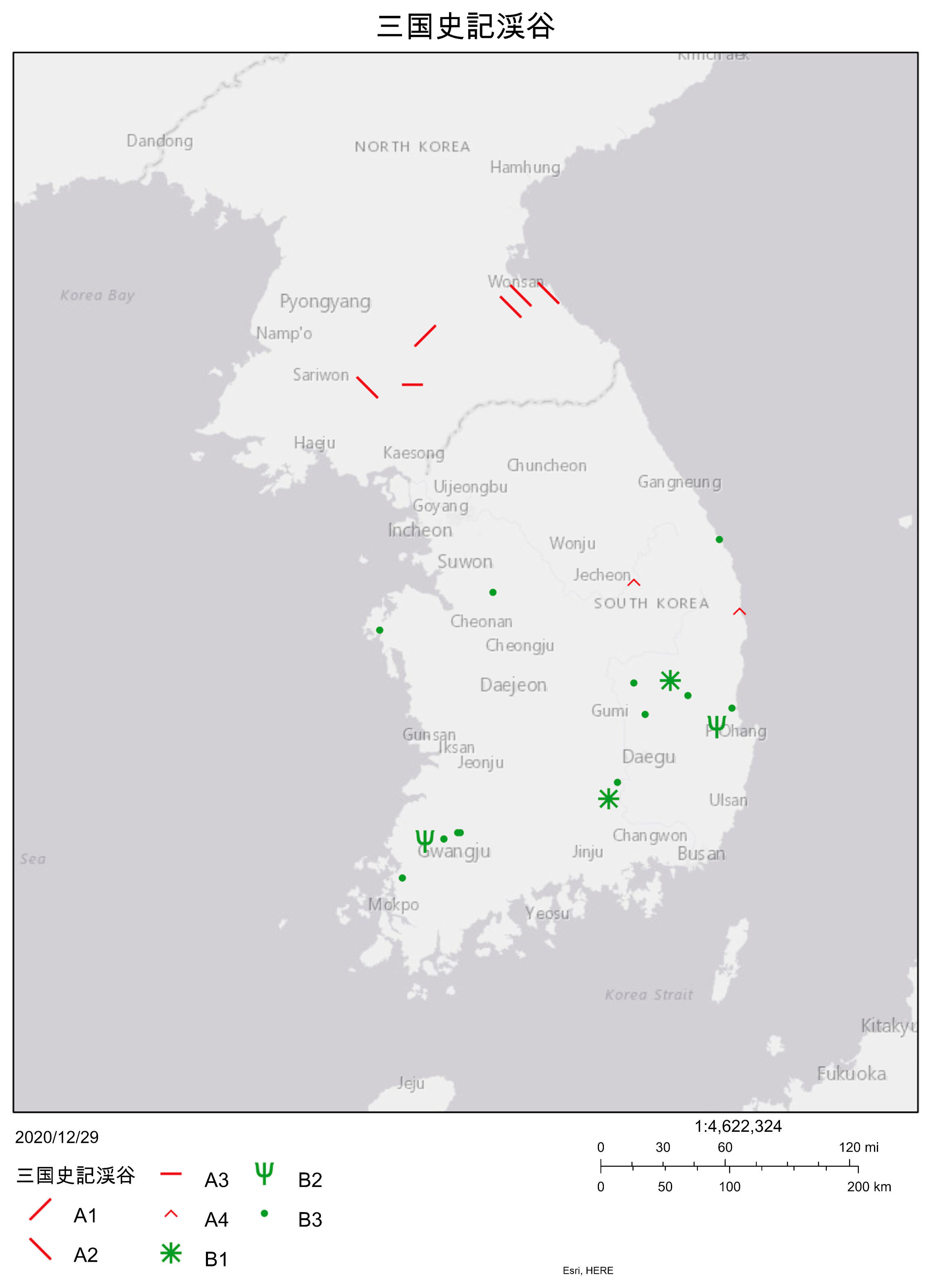

Geographical distribution of words for ‘valley’The correspondence between ‘頓呑旦’ in the Samguk Sagi and Old Japanese tani for ‘valley’ is well known. Type A1 is ‘-頓’ (old toponym): ‘-谷’ (new toponym). Type A2 is ‘-呑’: ‘-谷’. Type A3 is ‘-且’, which should be corrected to ‘旦’: ‘-谷’. Type A4 is ‘-且(旦)’, which appears among the old toponyms but lacks a counterpart meaning ‘valley’ among the new toponyms. Types A1–A3 appear in the far north of the territory, while type A4 appears in the southernmost part of Koguryo according to the Samguk Sagi. The Middle Chinese readings are *tuən for ‘頓’, *thən for ‘呑’, and *tɑn for ‘旦’, respectively. However, the actual reading of these three characters is uniformly reconstructed as *TA(N), neglecting both the aspirated/non-aspirated distinction and the round vowel medial. The nasal ending probably existed once, but likewise may already have disappeared by that time.

A word with similar meaning also appears: ‘甲比古次’ *KAPIKUTI: ‘穴口’ (‘strait’). ‘甲比’ corresponds to Old Japanese kapi, possibly an old loanword from Chinese ‘峡’ *ɦap (‘strait’) with parasitic vowel -i, accepting Middle Chinese *ɦ- for k-, since neither ɦ- nor h- existed in Old Japanese. Another reflection of this word in the Samguk Sagi is ‘甲忽’ *KA(P)KO(L): ‘穴城’ to the north of Yalu River. ‘穴口’ anakuti or ‘穴戸’ anato occur in the Kojiki, meaning ‘strait’. The name of this place later changed to ‘江華’ (‘river-flower’), reading ‘古次’, with Sino-Korean gocha changed into kkoch meaning ‘flower’ in Korean and ‘華’ (‘flower’) appearing through folk etymology.

In the south of the peninsula, a word written with ‘兮’ *KE occurs, also meaning ‘valley’. This word is probably a loanword from Chinese ‘溪’, hence green is used to denote its Sinitic origin in Figure 4. Type B1 is ‘-兮’: ‘-溪’ (‘valley’), type B2 is ‘-兮’: ‘-谿’ (‘valley’), and type B3 is ‘-兮’ in old toponyms, which lacks a related word meaning ‘valley’ among new toponyms. The Middle Chinese readings of ‘兮’ and ‘溪’ are *ɦei and *khei, respectively. It is possible that the two characters were read identically at that time.

‘Valley’.

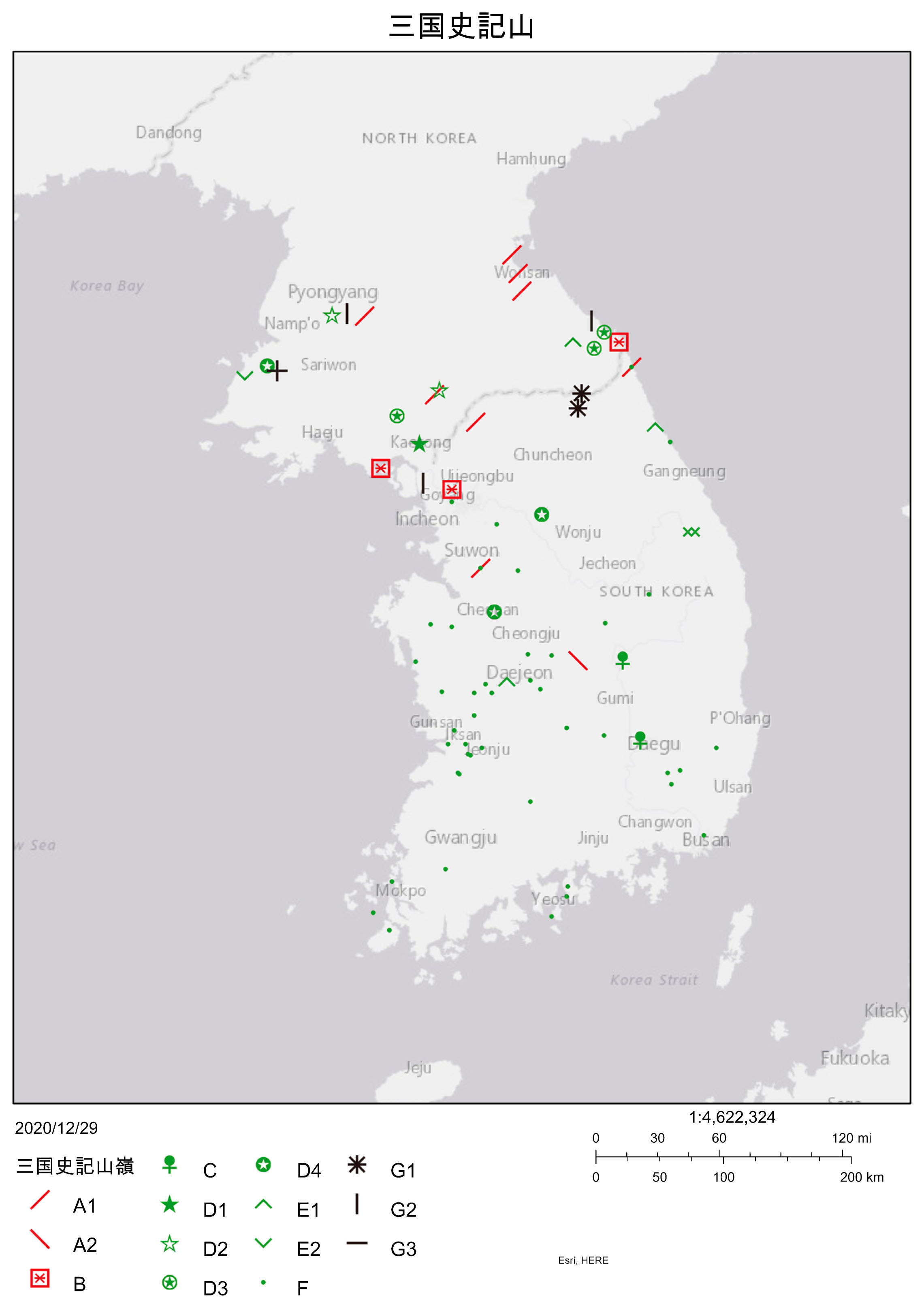

Figure 5 shows the geographical distribution of the words for ‘mountain’ and ‘ridge’. ‘-達’ is also a prominent reflection of Japonic words. Type A1 ‘-達’: ‘-山’ (‘mountain’) is related to Old Japanese takë (Old Japanese B type syllable denoted by umlaut) ‘(high) mountain’. However, it presents a severe problem that ‘達’ ends with *-t in Middle Chinese, but is changed to -r in Sino-Korean. Why was a Chinese character ending with *-k in Middle Chinese, for example ‘鐸’, not used to render -k- in Japonic? Lee (1968) offered a tentative reconstructed form for this word as *talke so that ‘達’ was used to render it. His position is analogous with other Japonic words using *-lt-, *-lg- based on comparison with Altaic languages, yet no corresponding concrete evidence exists for this particular word. In my view, Sino-Koguryo had a strong tendency to drop final elements, so the actual reading of ‘達’ was *TA without a -t ending, while the form for ‘mountain’ was also *TA without either -kë or -k. This equation thus presents no difficulty. Incidentally, the initial consonant of ‘達’ was *d- in Middle Chinese, so it is possible that there was no voiced/unvoiced distinction in Sino-Koguryo. As for type A2 ‘-達’, since the new toponym contains no element meaning ‘mountain’, it remains uncertain whether its old meaning was ‘mountain’ or not. Additionally, type A2 has a southern distribution, whereas type A1 appears across the central peninsula.

‘Mountain, ridge’.

Although type B ‘-達’: ‘-高’ has the same Chinese character as type A, ‘達’, the meaning is ‘high’. It has also been pointed out that it corresponds to Old Japanese taka-si (‘high’). Type C represents yet another usage of this Chinese character, ‘-達’: ‘大’ (‘big’) or ‘多’ (‘many’). Since both ‘大’ *dɑi and ‘多’ *tɑ in Middle Chinese were probably read as *TA, identical to ‘達’, they are judged to be loanwords from Chinese.

The correspondence seen in type D1 ‘-𡊠’: ‘-岳’ (‘high mountain’) reveals the meaning of the Chinese character ‘𡊠’ which is otherwise rarely used, since type D2 ‘-押’: ‘-嶽’ (‘嶽’ and ‘岳’ are different Chinese character forms of the same word) shows that ‘-押’ and ‘-𡊠’ are the same word. In Middle Chinese, ‘押’ and ‘甲’, the phonetic part of ‘𡊠’, end with *-p, while ‘嶽’ and ‘岳’ end with *-k. However, as endings were possibly dropped, the reconstructed form for these characters is *KA. Based on this phonetic similarity or equality, it may be concluded that ‘-押’ and ‘-𡊠’ are loanwords from Chinese. Although type D3 ‘-押’ does not include the meaning ‘mountain’, it is fairly safe to treat it as belonging to the same type, as in the case for Type D4 ‘-岳’. Types D1–D4 are distributed across the central region of the peninsula.

Type E1 ‘-峴’: ‘-嶺’ (‘ridge’) is the lower peak of a mountain. There is one equation between ‘-峴’ and ‘-嶮’ (‘ridge’), so it is possible that ‘見’, the phonetic of ‘峴’, represents the sound *KE, originating from ‘-嶮’ *hiɛm in Middle Chinese. This may also be treated as a loanword from Chinese. Type E2 ‘-峴’ occurs in the far northwest of the area.

Type F ‘-山’: ‘-山’ (‘mountain’) is simple and straightforward. This Chinese loanword is found throughout the southern district. This may reflect the Korean word for ‘mountain’, *mori (cognate with Japanese mori 森) > moi > mø, changing into the word ‘tomb’ since tombs are built in mountains. To avoid a homonymic clash, the word for ‘mountain’ adopted a Chinese loanword despite belonging to basic vocabulary.

From the equation of Type G1 ‘-波兮’: ‘-峴’, the meaning of ‘波兮’ is revealed to be the same as ‘峴’, as is the case for Type G2 ‘-波衣’: ‘-峴’. Type G3 ‘-波衣’ lacks a counterpart meaning ‘mountain’. Murayama (1961) says that: “In my view, 波衣 páui > 波兮pahyei > *pafoi, the later can be considered as a cognate with Japanese ipafo < *i-pafo ‘rock’.” However, ipafo is contradictory notation, and for consistency should be spelled as ipapo or ifafo. Moreover, this word should first be divided into ipa plus po. Nevertheless, pa can be regarded as the same element in ‘波兮’ and ‘波衣’. Lee (1968), however, considers that it corresponds to the Middle Korean pahoi. Since there are two possibilities, black is used to indicate its uncertain origin.

Geographical distribution of the words for ‘city’ and ‘burg’‘Rivers’, ‘valleys’, and ‘mountains’ are natural features that exist anywhere and at any time, whereas ‘villages’, ‘towns’, and ‘cities’ are the products of civilization with differences of size and style. Three different ways are used to denote kinds of ‘city’ in the Samguk Sagi. Although they have distinct distributions, their concrete styles may differ to some extent.

In the northern area, including north of the Yalu River, type A1 ‘-忽’ *KO(L): ‘-城’ (‘burg’) and similar subtypes are dominant. Type A2 is ‘-骨’ *KO(L): ‘-城’ (‘burg’) and type A3 is ‘-忽’ *KO(L): ‘-郡’ (“county”). Types A4 ‘-忽’ and A5 ‘-骨’ do not have counterparts denoting their meaning, but as these characters occupy the final position it seems reasonable to treat them as denoting the same administrative unit. The initial consonant can be *H, and the final consonant can be *T or with vowel *O or without second syllable. Shiratori (1905–1906) and Lee (1968), among others, have pointed out that these are loanwords from Tungusic, *xoto ‘valley, burg’, which has a related word in Mongolic as well. In Figure 6, orange is used for types A1–A5 to show their Mongolic/Tungusic origin.

“town” and “burg”

It is clear from archeological evidence that these cities were surrounded by stone walls in the continental burg style. It is not surprising that such settlements later spread to the southern area of the peninsula and that toponyms with ‘-忽’ are consequently distributed sporadically in the south. Conversely, 12 cities of type A1 were located north of the Yalu River, but since their exact locations are unknown it is impossible to plot them in Figure 6. They are: ‘節城, 蕪子忽; 豊夫城, 肖巴忽; 䄻城, 波尸忽; 大豆山城, 非達忽; 甘勿主 城, 甘勿伊忽; 屑夫婁城, 肖利巴利忽; 鈆城, 乃勿忽; 鷲岳 城, 甘弥忽; 積利城, 赤里忽; 木銀城, 召尸忽; 梨山城, 加 尸達忽; 穴城, 甲忽.’

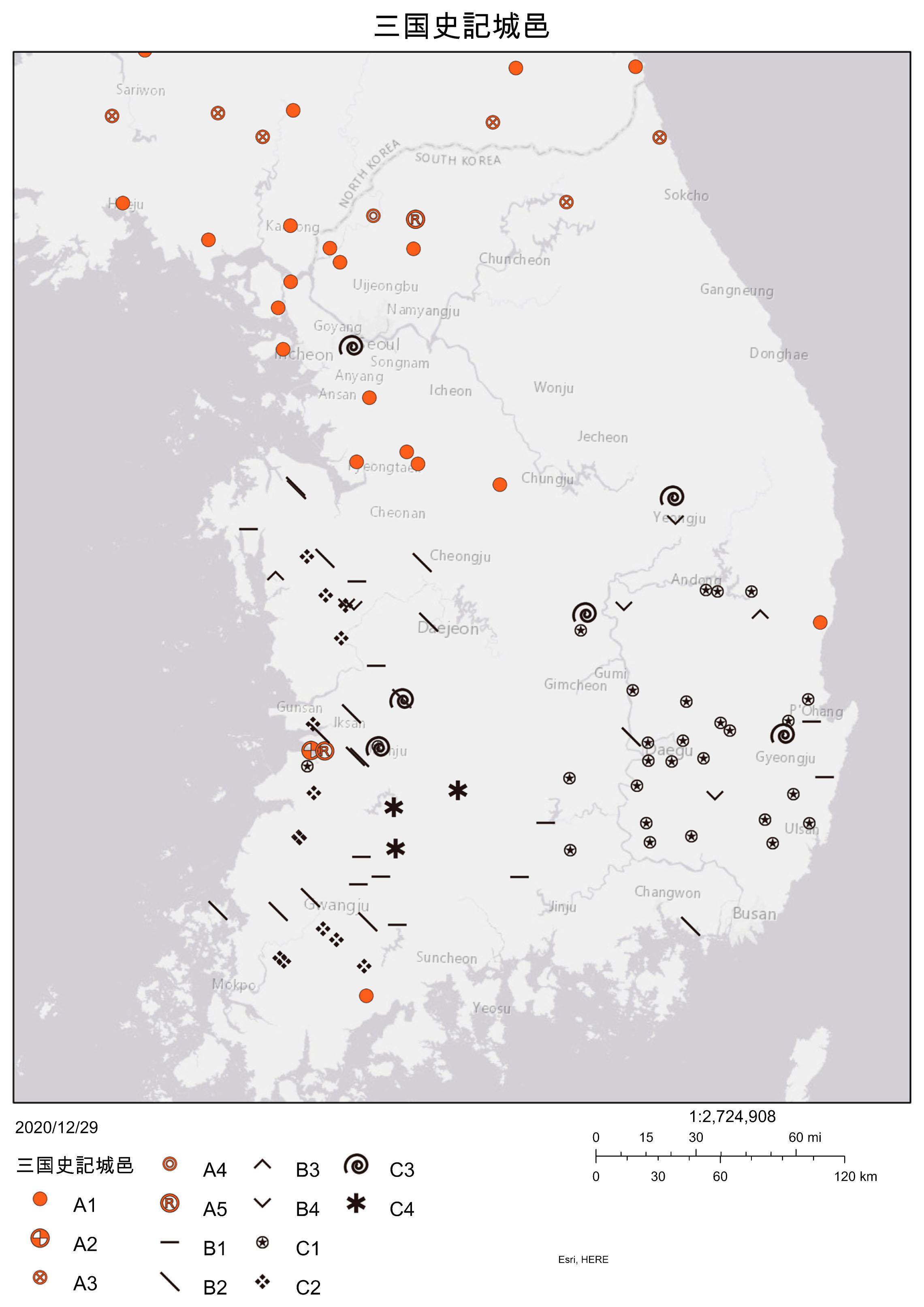

Two major types, B and C, occur in the southern area as seen more clearly in Figure 7. Only characters occupying the final position are included in these types. Many theories have been proposed concerning their etymology, a detailed examination of which will be undertaken separately in the future. Given their presently indeterminate origins, places of types B and C are marked in black.

Enlarged map of the southern distribution of ‘town’ and ‘burg’.

There are four subtypes for type B: type B1 ‘-支’ *KI, type B2 ‘-只’ *KI, type B3 ‘-己’ *KI and type B4 ‘-巳’ *KI. Regarding type B4, the sound of ‘-巳’ should be something like *SI; however, it can be treated as a misprint for type B3 ‘-己’ *KI. Type B seems to be distributed peripherally around the southern area, both in Baekje and Silla.

As for the geographical distribution of the subtypes of type C, type C1 ‘-火’ *PUR tends to occupy Silla, while type C2 ‘-夫里’ *PURI is exclusively distributed in Baekje. Type C3 ‘-伐’ *PUR appears in both Baekje and Silla, but type C4 ‘-坪’ *PUR is restricted to Baekje in this material.

Linguists have previously tended to examine only the so-called Koguryo toponyms included in Volumes 35 and 37, arriving at the conclusion that Japonic-origin toponyms are concentrated in the central part of the Korean peninsula. In this paper, so far as the examined terms are concerned, toponyms throughout the area covering Silla, Koguryo, and Baekje were exhaustively scrutinized. Not only were Japonic-origin words identified, but also Chinese, Mongolic and Tungusic loanwords as well as Korean elements.

A comparison of four maps shows the Japonic elements are distributed mainly in the central area of the peninsula, as observed previously. Nevertheless, there are some Japonic elements in the northern parts of Silla and Paekje. Sinitic loanwords are widely distributed, especially in the southern area in the cases of ‘valley’ and ‘mountain’, hiding the original language layer. The area of Silla and Paekje seemingly had a strong tendency to adopt Sinitic-origin toponyms, especially in comparison to Koguryo. As for ‘town’, the Mongolic and/or Tungusic word is dominant in the northern part of Amnokgang as well as the central district. Maybe this is due to the difference in the town style: Koguryo adopted round, fortified burgs to protect itself from attacks by the iron-weapon-equipped cavalry of the northern tribes. Only four-word final units were studied in this research. It will be possible to determine the geographical distribution of each human group more precisely if the elements of the stem part of toponyms are examined exhaustively in the near future.

This work was supported by KAKENHI JP18H05510 and JP18H00670.