2022 Volume 130 Issue 2 Pages 161-169

2022 Volume 130 Issue 2 Pages 161-169

Diarrhea is among the most common causes of death in children under five years of age. Infants are particularly at risk of ingesting pathogens directly or indirectly because of their frequent oral contact with a variety of objects. In hunter-gatherer societies, the widespread use of alloparenting, in which the infant is cared for by someone other than the biological parents, may play an important role in reducing the risk of infection from oral contact in infants. This study explored the relationship between infant oral contact behavior and diarrhea as well as the effects of alloparenting on infant oral contact behavior and diarrhea in hunter-gatherer societies. We conducted an interview on infant diarrhea and a 6-hour direct observation focused on oral contact and alloparenting of 6 infants (2–28 months) and 29 caregivers (≥4 years). During the observation period, the infants had frequent contact with objects with high risk of infection, with a median of 10.5 events (range, 0–49 events), and 50% (n = 3) had diarrhea. In addition, infants mainly ate with their hands or from the hands of their caregivers, and there was no hand-washing behavior before eating, suggesting that hand-feeding may increase the risk of transmission of pathogens. Our results also showed that the number of caregivers prevented diarrhea in infants. Furthermore, alloparenting of the unique child-rearing patterns of hunter-gatherers contributed to blocking the infants’ contact with objects with high risk of infection. These study findings suggest that alloparenting may play a significant role in reducing the risks of infant diarrhea and infection by oral contact behavior, even when the risk of transmission of pathogens through oral contact among infants may be high, such as in hunter-gatherer societies.

In 2017, more than 530000 children under the age of five died from diarrhea worldwide (Dadonaite and Ritchie, 2018). Infectious diseases such as diarrhea are a major cause of death in children under five years, and have been identified as a particular problem in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia (UN IGME, 2019). A previous study analyzing nine studies from five countries (Bangladesh, Peru, Guinea-Bissau, Brazil, and Ghana) found that diarrhea was a risk factor for stunting in children at age 24 months (Checkley et al., 2008). Furthermore, a previous study based on data from the Demographic and Health Survey of children in Malawi, a Sub-Saharan African country, also showed that diarrhea increases the risk of child wasting, making it a risk factor for child malnutrition (Ngwira, 2020).

Fecal pathogen exposure contributes to this diarrhea-associated health risk in children. A prospective cohort study of 203 children aged 6–30 months in rural Bangladesh suggested that high Escherichia coli levels in the soil of children’s playgrounds may be linked to an increased risk of intestinal infection in children (George et al., 2018). In addition, a previous study assessed the home environment using objective indicators such as water quality, toilet condition, and hand-washing facilities, and investigated the relationship between child health and the environment. The study found that children living in homes with good sanitation had a lower risk of developing parasitic infections and experienced better development than those living in contaminated environments (Lin et al., 2013). This suggests that a good sanitation environment is important for protecting children’s health.

The route of transmission of fecal pathogens is represented in a schematic F-diagram with transmission via fluids, fingers, fields, flies, and food (Wagner and Lanoix, 1958). In particular, infants spend much time on the floor, crawling on all fours and moving around on the ground during play, so they are exposed to a wide range of objects (Tulve et al., 2002). As this oral contact behavior is common in infants (Moya et al., 2004), infants are considered at high risk of exposure to pathogens through oral contact. In fact, in areas where livestock are kept, infants are at higher risk of frequent direct ingestion of livestock dung (Reid et al., 2018; Ngure et al., 2019). In particular, soil and feces contain high levels of E. coli, and direct oral contact with soil and feces can lead to diarrhea and other health risks (Pickering et al., 2012; Ngure et al., 2013). Previous studies have shown that oral contact behaviors such as eating soil are risk factors for parasitic infections (Doni et al., 2015), diarrhea (Shivoga and Moturi, 2009), and stunting (Perin et al., 2016) in children. In addition to soil and feces, objects such as infant toys and plates act as a pathogen transmission routes (Julian et al., 2013; Vujcic et al., 2014).

A caregiver’s action of washing their own hands before feeding an infant is important to prevent the transmission of pathogens through oral contact (Davis et al., 2018). Because infants are highly dependent on others, caregivers play an important role in preventing oral contact infections. Mothers of young children work together with others to share the burden of parenting (Sear et al., 2003; Kramer, 2005). Previous studies reported that alloparenting, in which people other than biological parents take up childcare on their behalf, may positively impact child survival (Sear et al., 2002; Sear and Mace, 2008). In hunter-gatherer societies, breast-feeding mothers face more severe trade-offs between childcare and subsistence activities due to various physically demanding hunting and gathering activities (Hurtado et al., 1992; Gurven and Kaplan, 2006; Meehan, 2009). For this reason, alloparenting is widespread and commonly used in hunter-gatherer societies (Crittenden and Marlowe, 2008; Hill and Hurtado, 2009; Page et al., 2019), and several studies have examined the impact of alloparenting on child health (Ivey, 2000; Meehan et al., 2014; Kramer and Veile, 2018).

The Baka people are a group of hunter-gatherers who live in Cameroon, the Republic of Congo, Gabon, and the Central African Republic. An estimated 25000 Baka people live in the southeastern part of Cameroon (Joiris, 1998). They lead a nomadic life, but from the 1950s onward, under the policy of the colonial government, they began to settle in villages close to the main roads (Sato, 1992). However, even today, dependence on forest resources and the practice of spending long periods of time in the forest away from the village for hunting and gathering activities persists (Hagino and Yamauchi, 2016; Martin et al., 2020). In our previous study (Konishi et al., 2021), we found that in a semi-sedentary village of Baka hunter-gatherers in Cameroon, many people practiced open defecation and there are some problems with the sanitation facilities introduced by outsiders. The study also showed that drinking water tested positive for total coliforms but was not directly associated with diarrhea in children. This suggests that diarrhea in infants may be caused by factors other than drinking water and suggests the need to focus on infants’ oral contact behaviors. However, only a few studies have directly observed oral contact behavior in infants in hunter-gatherer societies and examined the relationship between oral contact behavior and diarrheal diseases. Furthermore, there is a lack of research on the role of hunter-gatherer alloparenting in infant oral contact behavior and diarrhea, so it is important to accumulate more research data.

Thus, this study had two main objectives. The first was to characterize the oral contact behavior of infants in a hunter-gatherer society and explore the routes of transmission of diarrhea by recording the objects infants made oral contact with, and how often, through direct observation. The second was to determine the effects of alloparenting on infant oral contact behavior and diarrhea in a hunter-gatherer society using direct observation to record the attributes of caregivers and the amount of parenting time they spend with the infants.

The research area included three Baka villages (A village, S village, M village) located near the center of Lomié, Haut-Nyong Department, in the East Region of Cameroon. All three villages were semi-sedentary and located along a trunk road. These three villages were within a 3-km radius of one another. Fieldwork was conducted during February and March 2020. The total population in the research period was 146 people in A village, 117 in S village, and 49 in M village. People living in villages were engaged in both agricultural and subsistence activities, such as hunting, gathering, and fishing, and shifting between villages and forest camps (for further details of this demographic including their daily life, see Yamauchi et al., 2000, 2009).

The participants of this study were six Baka infants (three boys and one girl in A village, one girl in S village, and one girl in M village) and their caregivers (including parents). Infant age estimates were made in months by asking their mothers and others related to them. The mean age of the six infants was 13.3 ± 8.0 months (range, 2–28 months). Despite one child being 28 months, in this article all of them will be referred to as infants. Caregiver ages were estimated in years by interviewing them and adults who knew them. In this study, those who were married or 15 years or older were considered adults, while those under 15 years of age were considered children. Child caregivers were divided into two groups (younger and older children), with an estimated age of 10 years (the start of the pubertal growth spurt) as the cutoff (Hagino et al., 2013). The total number of caregivers was 29 (6 men, 13 women, 3 boys, and 7 girls). In addition to mothers, those involved in childcare were fathers, grandmothers, great-grandmothers, other adults, older siblings, and other children.

Interview about infant diarrheaAfter each observation study, the mother of the infant was interviewed about her infant’s diarrhea incidence in the past two weeks. Diarrhea was defined as the passage of three or more loose or liquid stools per day (WHO, 2017).

Direct observation of infants and caregiversA mixed-method observational study was conducted to assess enteric pathogen exposure pathways (especially oral contact events) and parenting activities for infants. These two types of observations were performed simultaneously on one infant. Both observations per infant lasted 6 h (07.00–13.00).

Oral contact data for infants were collected by direct observation. The researcher observed and recorded in the field notes the name and frequency of all objects that came in contact with the infant’s mouth. Oral contact events were defined as when an object or food came into contact with an infant’s mouth for ingestion and other purposes. If two or more items came into contact with the infant’s mouth at the same time, only the more prominent object of the two was considered to be in contact. Contact events were categorized as a nipple, an object, an infant’s own hand, food, liquid, and a person’s body part. As for the objects, we divided these into those with high risk of infection and those with low risk. This criterion was based on whether the risk of being contaminated with soil was high or low, and was determined based on the local conditions. In the present study, as we were unable to identify the level of contamination of each contact object due to the field condition of the tropical rainforests of the study site, we used the risk of soil contamination as a criterion. Previous studies have shown that even a small amount of soil can contain a large number of E. coli, so contact with soil-contaminated objects is considered to present a high risk of infection (Pickering et al., 2012; Ngure et al., 2013).

Parenting activity time in minutes for each caregiver (including parents) was observed and recorded in the field notes. Parenting activity time was defined as the total time for the two types of caregiver activities: the time that the caregiver has physical contact with the infant for parenting; and the time that the caregiver keeps the infant within arm’s reach for parenting.

Study ethicsThis study was approved by the ethics committee of the Graduate School of Health Sciences, Hokkaido University (20–9). Participation in the study was voluntary. The study objectives and methods were explained to the infant’s parents, other caregivers, and the village chiefs in French and Baka, which are the local languages. Consent was obtained from the infant’s parents, other caregivers, and the village chiefs.

Each infant was labeled A–F in ascending order of age. The interview results showed that half of the participants suffered from diarrhea (Table 1). However, during the observation period, no patient had diarrhea symptoms.

| A | B | C | D | E | F | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | Female | Female | Male | Male | Male |

| Age (months) | 2 | 8 | 12 | 14 | 16 | 28 |

| Diarrhea | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No |

Table 2 summarizes the numbers and types of infant oral contact events for each infant. The results indicated that the older infants E and F had more than 200 events with food and no contact with nipples. On the other hand, younger infants A, B, C, and D were observed nursing and were in contact with their mothers’ nipples. Only infant A also had contact with the nipple of a great-grandmother once. There were 16 different types of objects (4 with low risk of infection, 12 with high risk of infection). Infant D had the most frequent contact with objects with high risk of infection such as branch and soil; he vomited during the observation. Infant A had no contact with objects with high risk of infection during the observation. Infant B had the most frequent contact with her own hands among the participants (80 events).

| Oral contact type | A | B | C | D | E | F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nipple | 12 | 42 | 13 | 69 | 0 | 0 |

| Object (Low risk of infection) | 18 | 0 | 11 | 22 | 16 | 10 |

| Clothes | 18 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| Toothbrush | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 0 |

| Utensils | 0 | 0 | 8 | 22 | 0 | 0 |

| Plastic bottle | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Object (High risk of infection) | 0 | 3 | 11 | 49 | 14 | 10 |

| Branch | 0 | 0 | 11 | 15 | 0 | 0 |

| Shoes | 0 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 14 | 0 |

| Toy | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 0 |

| Leaf | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Battery | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Metal | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Paper | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Aluminum can | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Ant | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Snail | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Stone | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Soil | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 0 | 0 |

| Infant’s own hand | 23 | 80 | 7 | 41 | 9 | 47 |

| Food | 11 | 62 | 84 | 97 | 223 | 200 |

| Liquid | 5 | 3 | 9 | 7 | 17 | 12 |

| Water | 5 | 3 | 9 | 7 | 13 | 12 |

| Liquor | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| Person’s body part | 11 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 6 | 0 |

| Other’s arms | 11 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Other’s fingers | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Other’s lips | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 |

| Total | 80 | 195 | 137 | 286 | 285 | 279 |

Table 3 shows the parenting time for each caregiver and the number of caregivers per infant. The mean number of caregivers per infant was 4.8 ± 2.1; infant A had the highest number of caregivers (eight people). A variety of caregivers were observed; all infants except F had more than 250 min of parenting time, and younger infants A, B, C, and D had a relatively large number of caregivers. Mothers accounted for 65% of the total time spent in parenting activities, and were at the center of childcare. The total parenting time of children including siblings accounted for 19%, which was second to the mother. Fathers of infants A and F did not participate in the parenting due to travel to another village and hunting activities. Infants B, C, and E had no siblings, infants A and D had one older brother, and infant F had one older brother and one older sister. Only the brother of infant D engaged in parenting.

| Caregiver | A | B | C | D | E | F | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mother | 246 | 227 | 110 | 174 | 240 | 15 | 1012 (n = 6) |

| Father | 0 | 79 | 14 | 64 | 19 | 0 | 176 (n = 4) |

| Grandmother | 0 | 17 (n = 1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 (n = 1) | 28 (n = 2) |

| Great-grandmother | 10 (n = 1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 (n = 1) |

| Other adults | |||||||

| Male | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (n = 2) | 0 | 0 | 2 (n = 2) |

| Female | 17 (n = 1) | 0 | 4 (n = 2) | 1 (n = 1) | 0 | 0 | 22 (n = 4) |

| Siblings | |||||||

| Male | 0 | 0 | 0 | 15 (n = 1) | 0 | 0 | 15 (n = 1) |

| Female | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Other children (older) | |||||||

| Male | 0 | 0 | 0 | 19 (n = 1) | 0 | 0 | 19 (n = 1) |

| Female | 3 (n = 1) | 0 | 193 (n = 1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 196 (n = 2) |

| Other children (younger) | |||||||

| Male | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 (n = 1) | 5 (n = 1) |

| Female | 41 (n = 4) | 26 (n = 1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 67 (n = 5) |

| Total | 317 (n = 8) | 349 (n = 4) | 321 (n = 5) | 275 (n = 7) | 259 (n = 2) | 31 (n = 3) | 1552 (n = 29) |

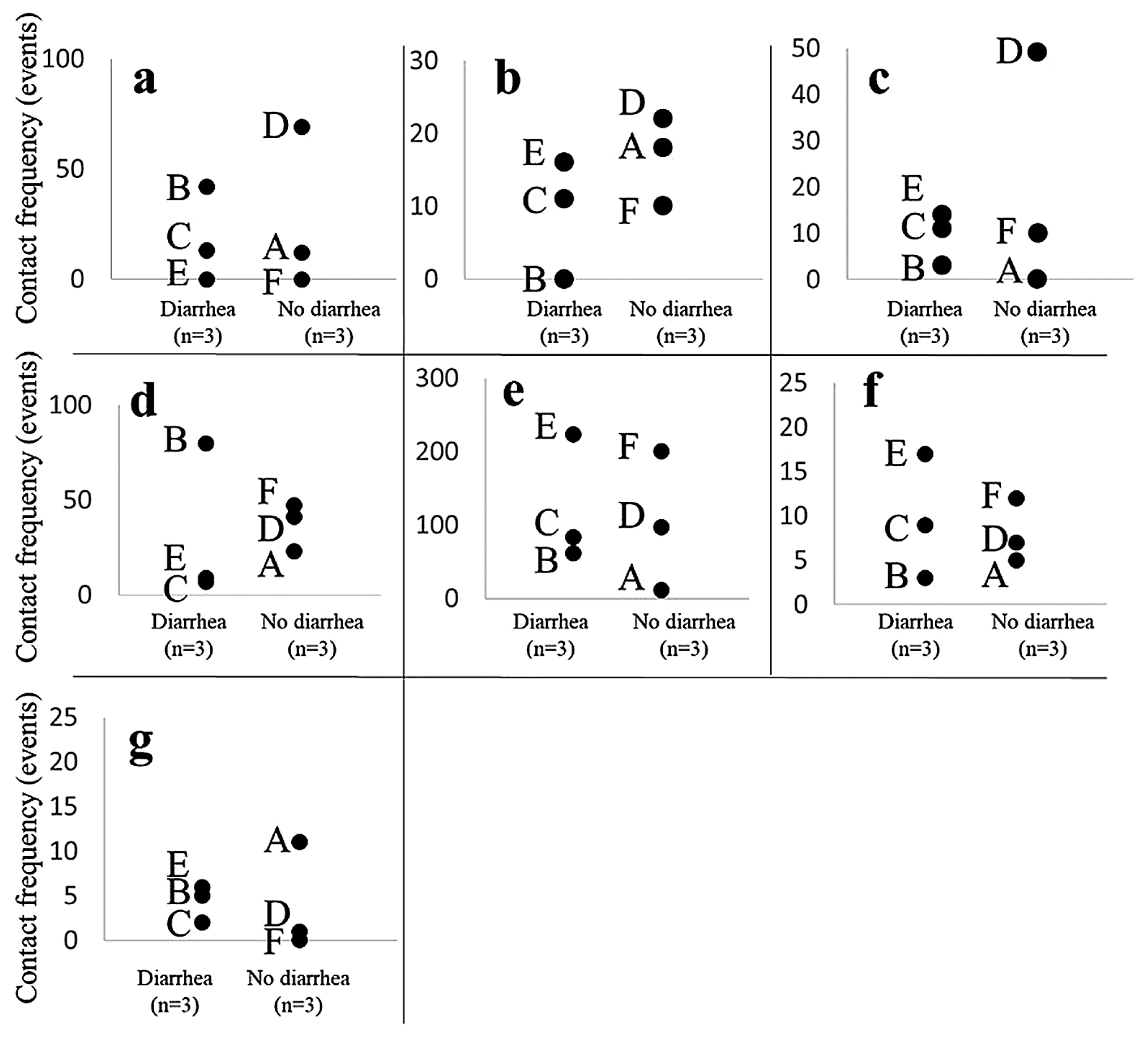

The relationship between each category of oral contact events (a, nipple; b, object with low risk of infection; c, object with high risk of infection; d, infant’s own hand; e, food; f, liquid; g, person’s body part) and diarrhea in each infant is shown in Figure 1. The results showed no characteristic association between them, and it was difficult to identify the contact material related to the presence or absence of diarrhea in the infants.

The relationship between infant diarrhea and oral contact by each category: (a) nipple, (b) object with low risk of infection, (c) object with high risk of infection, (d) infant’s own hand, (e) food, (f) liquid, and (g) person’s body part.

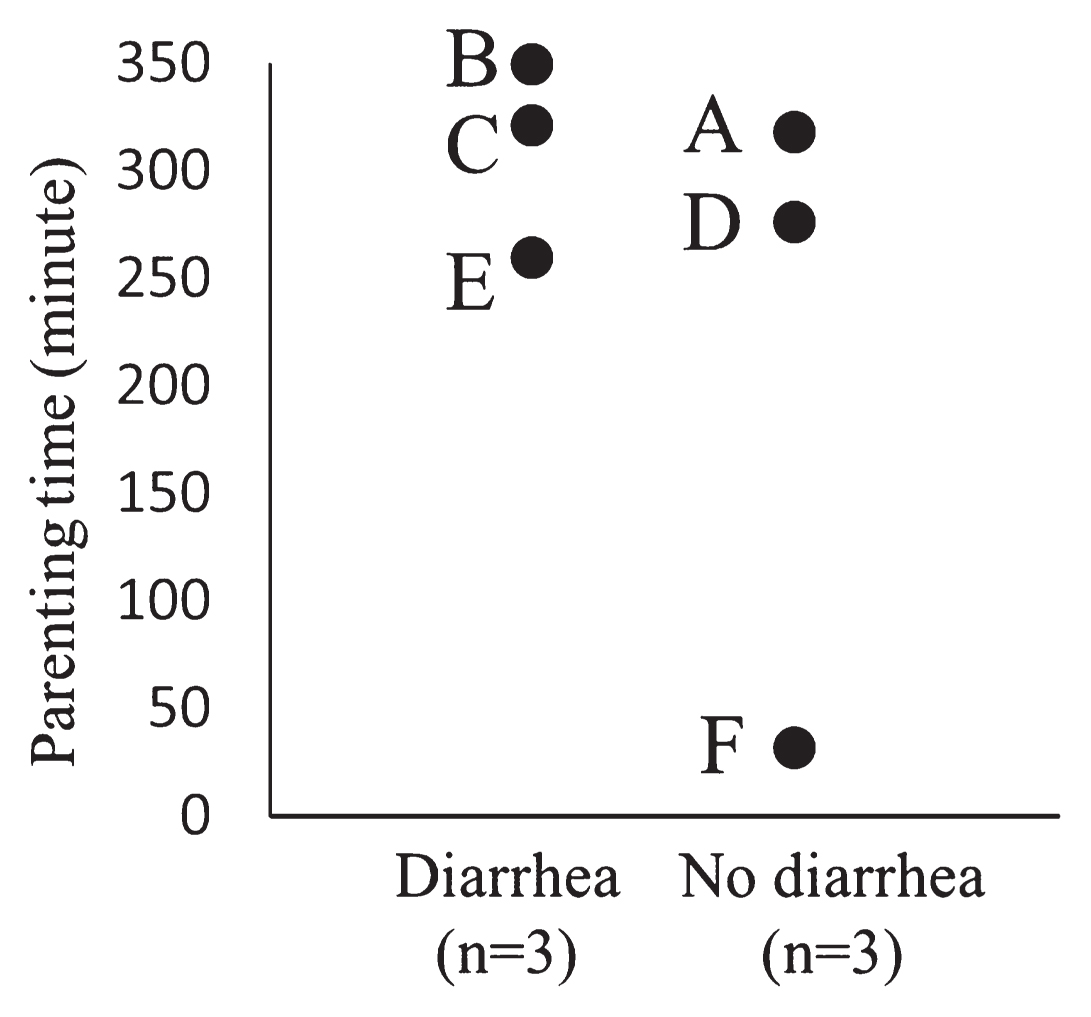

Figure 2 shows the relationship between diarrhea in infants and the number of caregivers per infant. As a result, the number of caregivers for infants A and D who did not suffer from diarrhea was seven and eight, respectively, which is a larger number of caregivers than the other infants. However, there was no clear relationship between infant diarrhea and total parenting time (Figure 3).

The relationship between infant diarrhea and the number of total caregivers per infant.

The relationship between infant diarrhea and the total parenting time per infant.

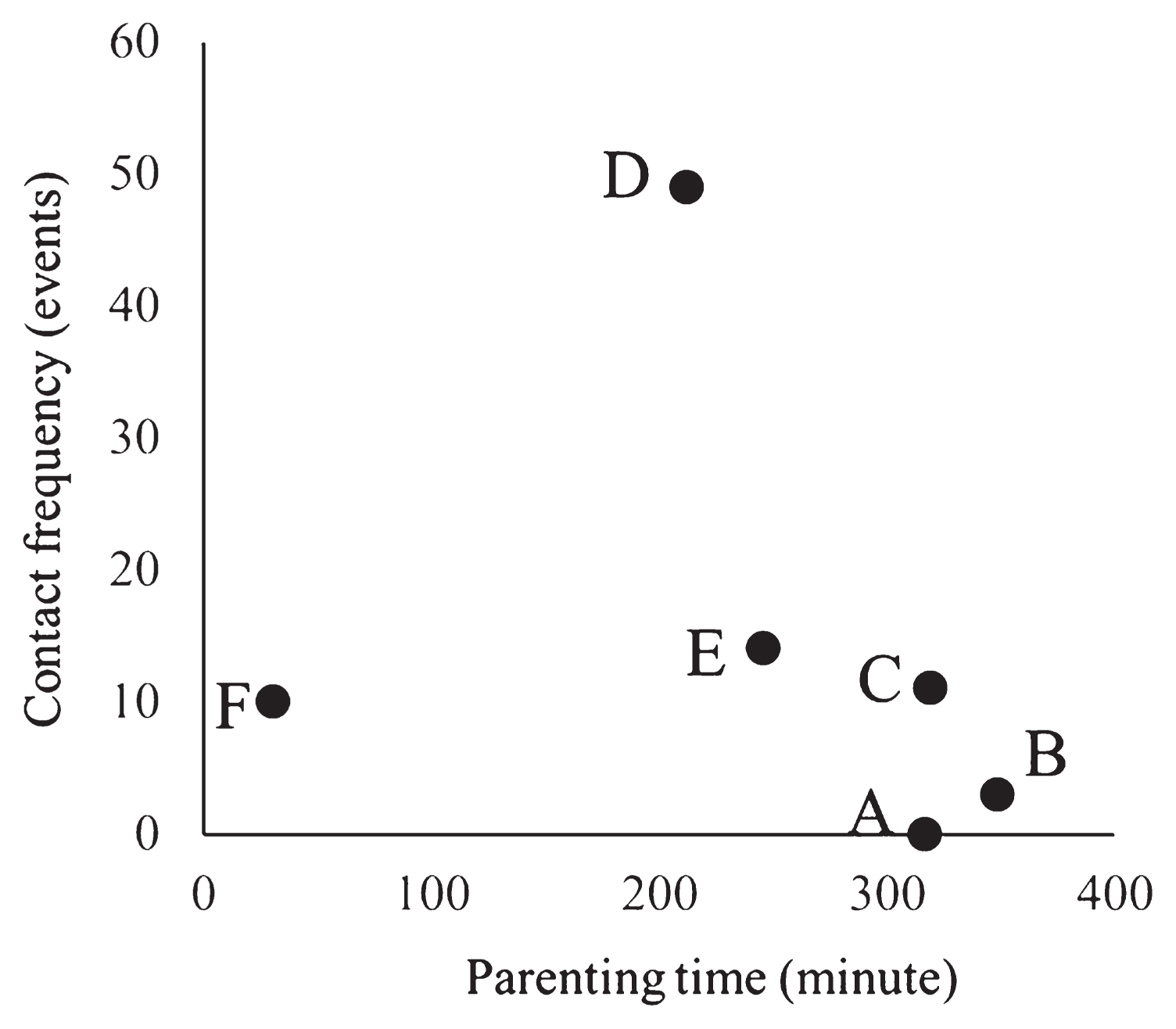

Figure 4 shows that there was no characteristic relationship between the amount of parenting time of each infant and the number of contacts with objects with high risk of infection. However, with the exception of infant F, who spent extremely little time under parenting, there was a tendency for the frequency of contact with objects with high risk of infection to decrease slightly as parenting time increased. Table 4 compares contacts with objects with high risk of infection during parenting and non-parenting time. Infants E and F had more contact with objects with high risk of infection during non-parenting time than during parenting time. Furthermore, infants A, E, and F had no contact with objects with high risk of infection during parenting time. Both infants D and E, who spent more than 1 hour in both parenting and non-parenting, had fewer contacts with objects with high risk of infection per hour in parenting than in non-parenting.

The relationship between parenting time and contacts with objects with high risk of infection per infant.

| A | B | C | D | E | F | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parenting (hours) | 5.3 | 5.8 | 5.4 | 4.6 | 4.3 | 0.5 |

| Non-parenting (hours) | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 1.4 | 1.7 | 5.5 |

| Oral contacts during parenting (events) | 0 | 2 | 10 | 25 | 0 | 0 |

| Oral contacts during non-parenting (events) | 0 | 1 | 1 | 24 | 14 | 10 |

| Oral contacts during parenting per hour (events/hour) | 0.0 | 0.3 | 1.9 | 5.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Oral contacts during non-parenting per hour (events/hour) | 0.0 | 5.5 | 1.5 | 16.9 | 8.3 | 1.8 |

This study found no clear relationship between infant diarrhea and the number of oral contacts of each type, making it difficult to identify the pathogen transmission route (Figure 1). When looking at the objects that infants came into contact with, depending on infant age, food accounted for the largest proportion of oral contacts (Table 2). During the observation study, infants rarely used spoons or other utensils to eat. Rather, they used their own hands or were fed by their caregivers, who also used their hands. Although it is unclear to what extent infants’ and caregivers’ hands were contaminated in this study, caregivers rarely washed the infants’ or their own hands before the infants’ meals. The importance of hand washing behavior in reducing the risk of exposure to pathogens and subsequently preventing the diarrhea risk has been demonstrated across countries by a number of studies (Burton et al., 2011; Curtis et al., 2009; Nguyen et al., 2006). Further research is needed to identify the transmission routes of pathogen exposure in this area, including measuring the contamination levels of each contact type.

Effect of alloparenting on diarrhea in infantsA previous study on the Efe, a hunter-gatherer ethnic group living in the Democratic Republic of Congo, suggested that the number of caregivers among infants at 1 year of age may positively affect subsequent infant survival (Ivey, 2000). Furthermore, the high number of camp members and the presence of grandmothers in the children’s camps positively contributed to the nutritional status of hunter-gatherer Aka children in the rainforest of the Congo Basin (Meehan et al., 2014). In the present study, the relationship between infant diarrhea and the number of caregivers showed that infants A and D, who did not have diarrhea, had more caregivers than other infants, suggesting that a higher number of caregivers involved in childcare may reduce the risk of diarrhea in infants (Figure 2), which is consistent with the results of previous studies of hunter-gatherer societies.

One of the possible reasons for this is that more caregivers could share the time spent on childcare, thus giving infants more attention and protecting them from oral contact with germ-contaminated objects. Previous studies have also cited family structure (multigenerational cohabitation) as a factor in Taiwanese children having less oral contact with hands and objects than their US counterparts, noting that multiple caregivers could pay more attention to infants’ behavior and reduce the risk of infants coming into contact with hands and objects (Tsou et al., 2015). In addition, a previous study on hunter-gatherer Aka reported that the caregivers (mainly grandmothers) reduce the physical burden on mothers who faced a trade-off between childcare and livelihood activities (Meehan et al., 2013). Such a reduction in the burden of childcare on mothers would enable them to pay more attention to the health of their infants. Furthermore, a previous study among Efe hunter-gatherers reported a significant positive correlation between the number of child caregivers and the time spent by mothers on food-gathering activities (Henry et al., 2005), suggesting that more caregivers make a significant contribution to mothers’ food security for their infants. On the other hand, infant F, who did not have diarrhea, had fewer caregivers, but was the oldest of the participants (28 months), which may have contributed to his immunity to certain pathogens (Pathela et al., 2006). These results suggest that the number of caregivers may be more important in terms of infant health in Baka hunter-gatherer society.

Effect of alloparenting on infants’ oral contactThis study found no association between oral contact with objects with high risk of infection and parenting time (Figure 4). However, infant F, who spent an extremely short amount of time in childcare compared to the other infants, was the oldest of the participants, somewhat independent, and may have had relatively low childcare needs. Excluding infant F, the results showed a slight tendency for oral contact with objects with high risk of infection to decrease with increasing parenting time. In addition, focusing on infants D and E, who have more than 1 hour of both parenting and non-parenting time, the number of oral contacts per hour with objects with high risk of infection were higher during non-parenting time than during parenting time (Table 4).

One of the factors may have been the caregiver’s attention to the infant, which prevented contact with objects with high risk of infection. In fact, during the observations in this study, there were several occasions when caregivers stopped infants from making oral contact with objects with high risk of infection. Another possible explanation is that by physically holding the infant the caregivers prevented them from coming into contact with objects presenting a high risk of infection. In a previous study comparing hunter-gatherer Aka and neighboring agrarian societies, it was shown that childcare in hunter-gatherer societies was characterized by the constant holding of the infant by the caregiver, frequent nursing, and prompt responsiveness, especially to signs of distress (Hewlett et al., 1998). In addition, a previous study has shown that this type of child-rearing is maintained even in the Baka, who were becoming more sedentary and agricultural than the Efe and Aka (Hirasawa, 2005). In the present study, this type of hunter-gatherer-specific parenting style may have reduced the risk of oral contact infection among infants.

This study has several limitations. The study included six infants observed for only 1 day and a 6-hour observation per day may not be sufficient; however, we employed the detailed recording of infant oral contact behavior, and alloparenting by many kinds of caregivers was based on a series of direct observation surveys over a 6-h period of the day, from 07.00 to 13.00, during which six infants were most active and the most of the oral contact behaviors were seen based on our direct observation. Hence, we believe that our observation time and method are reasonably acceptable. Few previous studies have analyzed oral contact data based on detailed observations of hunter-gatherer infants, making the present data very valuable. Although there is a large body of research on alloparenting among hunter-gatherers, a limited number of studies have examined the role of alloparenting from the perspective of infant oral contact and health status (diarrhea). A better understanding of infant health in hunter-gatherer societies, with a focus on detailed oral contact behavior and alloparenting, would be highly beneficial for improving infant health outcomes.

Similar to previous studies, the infants in the present study had oral contact with a variety of objects other than food. No infants had direct oral contact with feces, but contact with soil or other objects with high risk of infection were observed. However, there was no association between diarrhea and oral contact of any type, making it difficult to identify the route of transmission. In addition, infants fed mainly by hand or caregiver’s hand, and no hand-washing behavior before meals was observed, suggesting that hand-feeding may increase the risk of pathogen transmission. Our results also suggest that the number of caregivers played an important role in reducing the risk of diarrhea in infants. Furthermore, alloparenting of the unique parenting style of hunter-gatherers has the potential to reduce the risk of contact with objects with high risk of infection. Therefore, even when the risk of pathogen transmission through oral contact among infants is high in hunter-gatherer societies, alloparenting may play a significant role in reducing the risk of diarrhea among infants and the risk of transmission through oral contact behavior. To protect infant health, it is particularly important that caregivers beyond the mother’s household actively participate in parenting.

We would like to express our gratitude to all the participants who contributed to this research. We would also like to thank Mr. C.J. Nsonkali, Leader of Association OKANI, an indigenous NGO in Cameroon, and Dr. K. Hayashi for their great help during the field research. Sincere thanks go to Dr. A. Sai, Dr. S. Nyambe, and all members of the Laboratory of Human Ecology, Faculty of Health Sciences, Hokkaido University for their very helpful comments on the final draft.

The authors declare no competing interests

T.K. contributed to the conception and design of this study, collected and analyzed the data, drafted and revised the manuscript. T.Y. critically reviewed the manuscript and supervised the whole study process. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.