2019 Volume 1 Issue 2 Pages 21-30

2019 Volume 1 Issue 2 Pages 21-30

Objectives: Although musculoskeletal pain is considered to be a major contributor to chronic pain in Japan, there are few epidemiological studies on chronic musculoskeletal pain in workers. Presenteeism, defined as attendance at work in spite of the need to rest due to poor health, related to chronic pain causes a decrease in labor productivity, and its economic loss is said to be four times greater than that of Absenteeism. In this study, we examined the relationship between the actual state of musculoskeletal pain in workers and chronic musculoskeletal pain and labor productivity, with the goal of obtaining useful information to improve labor productivity. Methods: A questionnaire was distributed to 3,406 workers, of whom 2,055 were analyzed to determine the prevalence of chronic musculoskeletal pain and the affected body parts, and the influence of work-related factors and the degree of labor productivity loss due to chronic musculoskeletal pain. Results: 34.0% of subjects had chronic musculoskeletal pain. The most commonly reported pain site was “neck and shoulder”. Chronic musculoskeletal pain was significantly more common in people working overtime and in physical workers. Labor productivity was significantly lower in the group with chronic musculoskeletal pain than in the group without musculoskeletal pain, and it was significantly lower in the “neck and shoulder” and “lower back” groups than in the group without chronic musculoskeletal pain. Conclusions: Thirty-four percent of workers were engaged in work while experiencing chronic musculoskeletal pain. These workers had significantly decreased labor productivity. Efforts to improve conditions for workers with chronic musculoskeletal pain in each work type and working condition may improve labor productivity.

About 10–20% of the Japanese population suffer from chronic pain. The rate of complaints is particularly high for the lower back, neck, and shoulder regions1,2,3,4). Among types of chronic pain, surveys that focus on musculoskeletal pain5) have been conducted and demonstrated the high prevalence of musculoskeletal pain among those with chronic pain. However, fewer epidemiological surveys have investigated chronic musculoskeletal pain, and surveys targeting workers are particularly scarce. Given that workload can seriously affect the occurrence and chronicity of musculoskeletal pain in workers, it is important to clarify the relationship between work-related factors and musculoskeletal pain.

Chronic pain in workers leads to deterioration in job performance and labor productivity6). Determining the actual status of chronic pain in workers may provide useful information for estimating the extent to which chronic pain affects job productivity and the measures required to resolve the effects of chronic pain in workers. Decreased labor productivity due to poor health and/or disease in workers can be classified into the two concepts of “absenteeism”, defined as absence from work or suspension of work due to poor health, and “presenteeism”, define as attendance at work in spite of the need to rest due to poor health7). Economic losses due to presenteeism are reportedly about four times as large as those due to absenteeism8).

Studies from outside Japan have investigated the relationship between the chronicity of musculoskeletal pain in workers and decreased labor productivity, focusing on pain in the lower back, neck, shoulder, and arm9,10). In Japan, although one study has examined the relationship between presenteeism in workers with lower back pain and decreased labor productivity11), the relationship with musculoskeletal pain at other sites has not been investigated. Given that musculoskeletal pain among workers with chronic pain is prominent in body parts other than the lower back, it is important to clarify the relationship between presenteeism due to chronic musculoskeletal pain and decreased labor productivity.

We conducted this study to examine i) the relationship between musculoskeletal pain and work-related factors and labor productivity by presenteeism; and ii) the relationship between the body structures affected by chronic musculoskeletal pain and labor productivity by presenteeism. We expect that our findings will aid in the development of measures to prevent chronic musculoskeletal pain in workers and counter decreased labor productivity due to presenteeism.

In June 2016, a self-administered questionnaire was distributed to 3,406 workers at 118 workplaces of three different business types via the workplace’s health and safety staff or manager. The subjects were selected from workplaces at which the author or co-author work as an occupational physician. The questionnaire included information on this study’s overview and an informed consent form.

QuestionnaireBasic attributes: a questionnaire was used to collect the following information from each subject: basic attributes, such as name, age, sex, educational background, and present and past illnesses; and work-related factors, such as business type (manufacturing, financial, and retail), work type, job title, frequency of night shifts, and working hours. Business types were classified according to the Japanese Standard Classification of Occupations by the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. Work type was determined using a free-response question, and answers were classified into three categories: physical work (work that mainly requires using the body, such as work at a production site, driving, and maintenance), desk work (work that mainly comprises desk work, such as general office work, work with a personal computer, or computer-aided design), and emotional work (work that requires workers to control their emotions towards customers12), such as marketing, sales, and bank teller). The monthly frequency of night shift work, defined as work conducted from 22:00 to 05:00, was also determined. Working hours per day were determined using a free-response question based on the past 3 months. Monthly overtime work was calculated by subtracting 8 hours (the legal working hours per day in Japan) from the subject-provided working hours per day multiplied by 20 as the mean number of working days in a month.

Evaluation of musculoskeletal pain: Using diagrams of the human body, all subjects were requested to indicate the body parts in which they experienced musculoskeletal pain and the site of pain that most seriously affected their work (Appendix 1). Subjects with musculoskeletal pain were asked to indicate the duration of pain using a three-point Likert scale of less than 1 month, 1–3 months, and 3 months or more, and the frequency of pain using a four-point Likert scale of once or twice a month, 1 day a week, 2–5 days a week, and almost every day. According to the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP): “Chronic pain has been recognized as that pain which persists past the normal time of healing. With nonmalignant pain, three months is the most convenient point of division between acute and chronic pain”13). Therefore, we defined musculoskeletal pain lasting for ≥3 months as “chronic musculoskeletal pain”.

All subjects were classified into three groups: the No prevalence of Musculoskeletal Pain (NoMSP) group, comprising those with no musculoskeletal pain; the Temporal Musculoskeletal Pain (TMSP) group, comprising those with a musculoskeletal pain duration of 1 month or 1–3 months; and the Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain (CMSP) group, comprising those with a musculoskeletal pain duration ≥3 months. The site of chronic musculoskeletal pain was classified into five body areas (neck/shoulder, upper limbs, upper back, lower back, and lower limbs), and the prevalence of pain at each site was calculated. As many Japanese complain of “shoulder stiffness”, defined as “a collective term of a feeling of muscle tone (feeling of stiffness), heavy feeling, and dull pain from neck to scapular region” by Takagishi et al.14), we anticipated that the study subjects may report neck or shoulder pain as “shoulder stiffness” without a clear distinction between the two regions.

Work functioning impairment scale (WFun)The degree of labor productivity due to presenteeism was evaluated using the Work Functioning Impairment Scale (WFun), which assesses the degree of impaired work functioning that is not associated with a specific disease15,16). It comprised seven questions about the workers’ present physical impairment during work compared to a time when they were in good physical condition, evaluated using a five-point Likert scale of not at all, ≥1 day a month, ≥1 day a week, ≥2 days a week, and almost every day. The total score for each subject ranged from 7 to 35 points, with a high score indicating low productivity due to presenteeism.

Statistical analysisWe adopted a complete-case analysis for all comparisons. To understand the actual status of musculoskeletal pain in all workers, we calculated the complaint rate of musculoskeletal pain and the proportion of reports of sites that most seriously affected work among chronic musculoskeletal pain sufferers. To examine various chronic musculoskeletal pain-related factors and the relationship between presenteeism and chronic musculoskeletal pain, we compared individual and work-related factors in the three groups with regard to pain status (NoMSP, TMSP, and CMSP) using a chi-squared test and compared age and body mass index (BMI) using a one-way analysis of variance. We also compared WFun scores in these groups using linear mixed models (LMM). The LMM were constructed using WFun score as the dependent variable; age, sex, and group variables concerning the three pain statuses as fixed effects; and business type as a random effect. We used the Bonferroni method as a post-hoc test (p-values were multiplied by 3). To determine whether work-related factors were associated with a tendency toward chronic pain at a certain site, we subsequently used the chi-squared test to analyze the site of chronic musculoskeletal pain that most affected work according to business type, work type, and overtime working hours and, when statistical significance was observed, we used the adjusted residual analysis. To investigate the relationship between labor productivity by presenteeism and the site of musculoskeletal pain, we used the LMM to compare WFun scores among six groups, consisting of the NoMSP group and 5 CMSP subgroups according to the site of musculoskeletal pain. The LMM were constructed using WFun score as the dependent variable; age, sex, and group variables concerning six pain statuses as fixed effects; and business types as a random effect. We used the Bonferroni method as a post-hoc test (p-values were multiplied by 15). Analyses were conducted using the IBM SPSS 24.0J statistical software (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA).

Ethical considerationsThis study was conducted after obtaining the approval of the Ethics Committee of the University of Occupational and Environmental Health, Japan. The approval date was May 11, 2016 and approval number was H28-001. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Responses were collected from 2,154 of the 3,406 workers who were administered the questionnaire (recovery rate: 63.2%). Among the 2,154 respondents, 75 and 24 workers provided unclear or unknown responses for the site of pain that most affected their ability to work and the duration of pain, respectively, and were excluded from the analysis. The remaining 2,055 workers were ultimately enrolled and analyzed for chronic musculoskeletal pain.

The mean age of all enrollees was 41.9 (standard deviation: 12.4) years, and the proportion of male subjects was 75.7%. Among business types, 55.2% were involved in manufacturing, 29.0% in finance, and 15.8% in retail. Among work types, 48.5% performed physical work, 43.2% performed desk work, and 8.2% performed emotional work. Regarding overtime work, 63.6% of workers did not work overtime at all, whereas 8.9% of workers were engaged in overtime work for ≥60 hours a month (Table 1).

| Total | No prevalence of Musculoskeletal Pain group | Temporal Musculoskeletal Pain group | Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain group | p-valuea | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N=2,055) | (N=1,115) | (N=242) | (N=698) | ||||||

| Age, years | 41.9 | (12.4) | 41.2 | (12.6) | 41 | (12.9) | 43.2 | (11.9) | .002* |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 22.9 | (3.6) | 22.7 | (3.5) | 22.8 | (3.9) | 23.2 | (3.5) | .009* |

| Sex, % | |||||||||

| Male | 75.7 | 77.0 | 76.0 | 73.5 | .229 | ||||

| Female | 24.3 | 23.0 | 24.0 | 26.5 | |||||

| Present illness(es), % | |||||||||

| None | 78.2 | 82.5 | 77.7 | 71.1 | <.001* | ||||

| Exist | 21.8 | 17.4 | 22.3 | 28.8 | |||||

| Past illness(es), % | |||||||||

| None | 79.6 | 83.1 | 82.2 | 72.8 | <.001* | ||||

| Exist | 20.4 | 16.9 | 17.4 | 27.2 | |||||

| Educational background, % | |||||||||

| Junior high school | 2.9 | 2.5 | 5.0 | 2.7 | .122 | ||||

| Senior high school | 45.9 | 44.8 | 49.2 | 46.7 | |||||

| Vocational school | 10.1 | 9.8 | 7.9 | 11.5 | |||||

| College | 40.6 | 42.5 | 37.2 | 38.8 | |||||

| Unknown | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 0.3 | |||||

| Business type, % | |||||||||

| Manufacturing | 55.2 | 51.3 | 64.0 | 58.3 | .001* | ||||

| Finance | 29.0 | 32.1 | 22.3 | 26.4 | |||||

| Retail | 15.8 | 16.6 | 15.7 | 15.3 | |||||

| Work type, % | |||||||||

| Physical work | 48.5 | 48.1 | 55.4 | 46.8 | <.001* | ||||

| Desk work | 43.2 | 42.6 | 38.4 | 45.7 | |||||

| Emotional work | 8.2 | 9.3 | 5.0 | 7.4 | |||||

| Unknown | 0.1 | 0.0 | 1.2 | 0.0 | |||||

| Job title, % | |||||||||

| Non-executive | 81.2 | 81.8 | 84.7 | 78.8 | .085 | ||||

| Executive | 18.8 | 18.1 | 15.3 | 21.2 | |||||

| Night shifts per month, % | |||||||||

| None | 76.8 | 79.0 | 69.0 | 75.8 | .001* | ||||

| ≤3 | 5.5 | 4.4 | 11.2 | 5.4 | |||||

| ≥4 | 17.4 | 16.2 | 19.0 | 18.6 | |||||

| Unknown | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.1 | |||||

| Overtime hours/month, % | |||||||||

| None | 63.6 | 67.7 | 61.2 | 57.9 | <.001* | ||||

| <60 | 14.9 | 14.8 | 14.9 | 15.2 | |||||

| ≥60 | 20.6 | 16.7 | 22.7 | 26.1 | |||||

| Unknown | 0.9 | 0.8 | 1.2 | 0.9 | |||||

BMI, body mass index.

All data indicate mean (standard deviation) unless otherwise indicated

A total of 940 subjects (45.7%) complained that musculoskeletal pain affected their work, of whom 698 (34.0%) indicated that their musculoskeletal pain had become chronic. The site of chronic musculoskeletal pain that most seriously affected work was the neck/shoulder in 40.7% of workers, followed by the lower back and lower limbs in 33.8% and 10.9% of workers, respectively. Of those classified into the neck/shoulder group, 56.0% of subjects answered that both neck and shoulder were a pain site in the questionnaire.

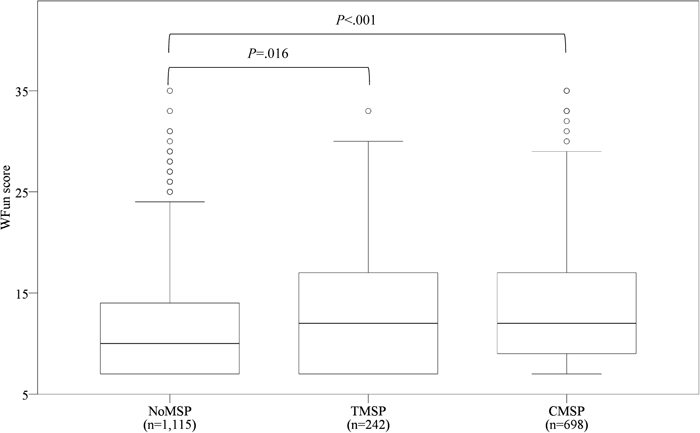

Comparison of basic attributes, work-related factors, and labor productivity among the three pain groupsSubjects were divided into three groups (NoMSP, TMSP, and CMSP) based on the presence or absence of musculoskeletal pain and its severity (acute or chronic). Basic attributes and WFun scores were compared among these groups (Table 1 and Figure 1). The mean age of workers was significantly higher in the CMSP (43.2; standard deviation, 11.9) than in the NoMSP group (41.2; standard deviation, 12.6). While BMI was significantly different by variance analysis, there was no significant difference among the groups. Significantly more subjects in the CMSP group were engaged in manufacturing among the three business types, and those in the CMSP group were more likely to engage in physical work than other work types. In contrast, the NoMSP group comprised a significantly larger number of workers not engaged in night shift work. With respect to working hours, the CMSP group comprised significantly fewer workers not engaged in overtime work but more workers engaged in overtime work for <60 hours or ≥60 hours per month. The CMSP group also comprised a significantly greater number of workers with illnesses that are currently being treated or were treated in the past. There were no significant differences in sex ratio, job title, or educational background among the groups (Table 1). The WFun score was significantly higher in the TMSP and CMSP groups than in the NoMSP group (Figure 1).

Comparison of WFun scores among the three pain groups.

NoMSP, no musculoskeletal pain; TMSP, temporal musculoskeletal pain; CMSP, chronic musculoskeletal pain; WFun, Work Functioning Impairment Scale.

The upper horizontal line of each box is the 75th percentile, the lower horizontal line is the 25th percentile, and the middle horizontal line is the median. The cross is the arithmetic mean and the vertical lines are the ranges of the data.

The Bonferroni method was conducted as a post-hoc test (the p-values were multiplied by 3)

The site of chronic musculoskeletal pain that most affected work was examined for each business type, work type, and overtime hours (Table 2). With regard to business type, significantly more manufacturing, finance, and retail workers reported pain in the lower back, neck/shoulder, and lower limbs, respectively. Among workers engaged in finance work, significantly fewer had chronic pain in the lower back or lower limbs compared to the other sites. In terms of work type, significantly more physical workers suffered from lower back pain or lower limb pain, and significantly more desk and emotional workers suffered from neck/shoulder pain compared to the other sites. In contrast, significantly fewer physical workers and desk workers experienced pain in the neck/shoulder and lower back or lower limbs, respectively. Regarding overtime hours, significantly more workers with overtime work of ≥60 hours a month reported having pain in the neck/shoulder and significantly fewer reported pain in the lower limbs.

| Site of chronic musculoskeletal pain | Business type | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (N=698) | Manufacturing (N=407) | Finance (N=184) | Retail (N=107) | p-valuea | ||||

| Neck/shoulder, % | 40.7 | 37.8 | 51.6 | ▲ | 32.7 | .001* | ||

| Lower back, % | 33.8 | 36.9 | ▲ | 27.7 | ▽ | 32.7 | ||

| Lower limbs, % | 10.9 | 10.6 | 6 | 20.6 | ▲ | |||

| Upper limbs, % | 9.2 | 8.8 | 8.7 | 11.2 | ||||

| Upper back, % | 5.4 | 5.9 | 6 | 2.8 | ||||

| Work type | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (N=698) | Physical work (N=327) | Desk work (N=319) | Emotional work (N=52) | p-valuea | ||||

| Neck/shoulder, % | 40.7 | 26.9 | ▽ | 52 | ▲ | 57.7 | ▲ | <.001* |

| Lower back, % | 33.8 | 40.4 | ▲ | 27.9 | ▽ | 28.8 | ||

| Lower limbs, % | 10.9 | 17.1 | ▲ | 5.3 | ▽ | 5.8 | ||

| Upper limbs, % | 9.2 | 11 | 8.5 | 1.9 | ||||

| Upper back, % | 5.4 | 4.6 | 6.3 | 5.8 | ||||

| Overtime hours/month | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (N=692) | None (N=404) | <60 (N=106) | ≥60 (N=182) | p-valuea | ||||

| Neck/shoulder, % | 40.9 | 37.4 | 42.5 | 47.8 | ▲ | .043* | ||

| Lower back, % | 34.0 | 34.7 | 34 | 32.4 | ||||

| Lower limbs, % | 10.7 | 13.1 | 10.4 | 5.5 | ▽ | |||

| Upper limbs, % | 9.0 | 10.1 | 7.5 | 7.1 | ||||

| Upper back, % | 5.4 | 4.7 | 5.7 | 7.1 | ||||

▲ and ▽ indicate significantly higher and lower values than expected, respectively, in residual analysis using chi-squared tests.

Since significant differences in WFun scores were observed among the six groups, multiple comparison tests were conducted to compare differences in the site of chronic pain (Figure 2). WFun scores for pain in the neck/shoulder and lower back were significantly higher in the CMSP group compared to the scores for the NoMSP group.

Comparison of WFun scores among the sites of chronic musculoskeletal pain.

NoMSP, no musculoskeletal pain; WFun, Work Functioning Impairment Scale.

The upper horizontal line of each box is the 75th percentile, the lower horizontal line is the 25th percentile, and the middle horizontal line is the median. The cross is the arithmetic mean and the vertical lines are the ranges of the data.

The Bonferroni method was conducted as post-hoc test (the p-values were multiplied by 15)

The prevalence of chronic musculoskeletal pain in our study was 34.0%, and the most common site of pain was the neck/shoulder. This conflicts with findings from studies targeting the general public3,4,5) and the National Livelihood Survey by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan17), which found that the most common site of chronic musculoskeletal pain was the lower back. This discrepancy in findings may be due to differences in the demographics of the surveyed subjects, particularly age. In fact, in the National Livelihood Survey, those that complained of subjective symptoms in the lower back were primarily aged 70 years and over, and were mostly considered retirees. In this study, we clarified that the prevalence of chronic musculoskeletal pain in workers is high, and that work-related factors affect the site of chronic musculoskeletal pain. It is possible that work-related factors affect the occurrence of chronic musculoskeletal pain, and detailed evaluation of such factors may help to prevent musculoskeletal pain from becoming chronic.

The fact that the CMSP group comprised significantly older workers compared to the other pain groups may indicate that pain reported by CMSP participants is attributable to age-related physical changes. The CMSP group included many physical workers, which is presumably because handling of heavy loads and working posture place a greater strain on the joints in the limbs and the lumbar vertebra (spine) compared with desk and emotional work. More workers with long working hours and night shift work had chronic pain, which may be attributable to physical load and mental stress due to increased working hours. Causes of chronic lower back pain include work-related mental factors, such as workplace stress, low job satisfaction, and lack of support from superiors18). Therefore, mental stress may also cause or exacerbate chronic physical pain.

The CMSP group had significantly lower labor productivity compared to the NoMSP group, which is consistent with findings from previous studies5,8,19,20). That the TMSP group also showed significantly lower labor productivity compared to the NoMSP group indicates the adverse impact of musculoskeletal pain on labor productivity. Therefore, establishing effective measures to prevent musculoskeletal pain in workers is important, not only to improve the health of individual workers but also to reduce economic loss in companies.

Relationship between the site of chronic musculoskeletal pain and labor productivityOur findings suggest that labor productivity is significantly lower in workers with chronic musculoskeletal pain, particularly those with pain in the neck/shoulder and lower back, compared to those with no pain. Therefore, implementing measures to prevent musculoskeletal pain specifically in the neck/shoulder and lower back may be effective in achieving a company-wide improvement in labor productivity. Additionally, the sites of chronic musculoskeletal pain were largely consistent with the main work features of each business type. Specifically, workers in manufacturing or retail are frequently engaged in work that requires standing, suggesting increased loads on the lower back and lower limbs, while workers in finance are mainly engaged in desk work using computers in a sitting position, suggesting that complaints due to visual display terminal work are likely to be associated with pain in the neck/shoulder. Indeed, significantly fewer workers in finance experienced chronic pain in the lower back and lower limbs. It is possible that workers with pain in certain body parts may not consider it sufficiently serious as to affect their work. This was the case when comparing the site of chronic musculoskeletal pain among work types. Based on this, establishing measures to reduce the prevalence of chronic musculoskeletal pain, with a focus on the neck/shoulder and lower back, and measures to reduce or prevent chronic musculoskeletal pain in particularly high-complaint body areas in each business type and work type, may be effective in improving labor productivity.

Exercises, such as gymnastics and dynamic stretching21), and strategies for improving working methods, such as optimizing worker posture22), are reportedly effective for improving chronic musculoskeletal pain. Pain-based functional disorders have also been improved by a combination of cognitive behavioral therapeutic approaches and exercise23). However, complicated and time-consuming methods are best avoided in actual workplaces. Exercise therapy is a convenient method that can be completed in a short time24) and has confirmed efficacy for reducing chronic lower back pain. Future studies should examine simple measures that improve chronic musculoskeletal in not only the lower back but also other body regions.

Limitations of this study and future prospectsSeveral limitations of this study warrant mention. First, because we adopted a complete-case analysis and it is possible that more workers with pain completed the questionnaire than workers without pain, a degree of selection bias may have been present. Second, given that the study was conducted using a cross-sectional design, it was impossible to clarify the causal relationship of presenteeism with chronic pain and decreased labor productivity. Third, we only examined the prevalence of pain among three types of businesses. As the site of chronic pain can differ among industries due to differences in working conditions, generalizations across other business types cannot be made. Fourth, with regard to the site of pain, every effort was made to increase the reliability of respondents’ answers by providing diagrams of the human body in addition to written information. Nevertheless, it was difficult to collect detailed information, such as the characteristics of the pain and whether the pain was topical or general. Moreover, we did not evaluate information concerning psychogenic pain (such as family environment, interpersonal relationships, problems in the workplace, or causes of pain), personal character tendencies, or cognitive aspects, and were, therefore, unable to assess the extent to which psychogenic pain contributed to chronic pain. As no specific definition of psychogenic pain is readily available and physical and psychogenic pain can sometimes coexist25), complete exclusion of psychogenic pain may be difficult, although this may be possible to some extent using special measures, such as expert interviews.

A more accurate investigation of the status of chronic musculoskeletal pain in workers would require a study that uses an interview method and compares pain among more types of businesses. Further, investigations into factors that might contribute to the chronicity of musculoskeletal pain, and longitudinal studies to estimate the causal relationship of presenteeism with chronic musculoskeletal pain and decreased labor productivity are warranted.

We found that 34.0% of subjects with chronic musculoskeletal pain engaged in work, and that these workers had lower job performance than those without chronic musculoskeletal pain. It is, therefore, important that both workers and companies establish effective measures to prevent or accommodate chronic musculoskeletal pain according to the most severely affected body parts among each business and work type.

We deeply appreciate the cooperation of the company employees who participated in this study. This study was conducted with FY2016 research funding from the Occupational Health Promotion Foundation in Japan.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest associated with this manuscript.

Diagram included in the questionnaire regarding the site of pain. The site of pain was indicated by the number corresponding to the site of pain or by a circle in the diagram in 8.