Abstract

Objectives: Propetamphos (PPT) is an organophosphate pesticide (OP) widely used to control insects in public health settings and methylethylphosphoramidothioate (MEPT) is a urinary exposure marker of PPT. The objectives of this study were to develop a biomonitoring method for urinary MEPT using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) and to measure urinary MEPT concentrations in occupational and non-occupational human populations. Methods: Analytes derivatized with pentafluorobenzyl bromide were analyzed by GC–MS and dibutyl phosphate was used as an internal standard. The validated method was applied to urine samples collected from occupational PPT sprayers (n=15), non-PPT sprayers (n=15) who did not spray PPT but sprayed other OPs, and control subjects (n=80) living in Aichi, Japan. Results: Calibration curves were obtained using standard-spiked pooled urine samples, and the coefficients of determination were ≥0.98. The limit of detection (LOD) was 10 μg/L. The within-run precision and between-run precision ranged from 17.5% to 19.4% and 10.4% to 18.1%, respectively. The detection rates of urinary MEPT in the PPT sprayers, non-PPT sprayers, and control subjects were 26.7%, 6.7%, and 2.5%, respectively. The concentration ranges for creatinine-unadjusted MEPT were <LOD–22.3, <LOD–21.9 and <LOD–13.8 μg/L, and creatinine-adjusted MEPT were <LOD–12.1, <LOD–12.7 and <LOD–7.9 μg/g creatinine, for the respective groups (PPT sprayers, non-PPT sprayers and controls). Conclusions: This study established a biomonitoring method that can measure urinary MEPT in spraying and non-spraying workers with exposure levels ≥10 μg/L.

Introduction

Organophosphate pesticides (OPs) are widely used in agricultural, industrial, household, and public health management applications worldwide1,2,3). They are generally potent environmental toxicants that induce neurotoxicity by inhibiting the activity of acetylcholinesterase4,5,6). Recently, even if no apparent inhibition of cholinesterase has been detected, OP exposure has been reported to be associated with various pathophysiological or developmental conditions, including behavioral problems7), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder8), autism spectrum disorder9), reproductive impairments10), endocrine disorders11), cardiovascular diseases12), and cancers13). To investigate these adverse endpoints in human populations with low-level OP exposure, the currently available biological monitoring (biomonitoring) method is a measurement of six urinary non-specific OP metabolites (collectively called dialkyl phosphates [DAPs]): dimethylphosphate, dimethylthiophosphate, dimethyldithiophosphate, diethylphosphate, diethylthiophosphate, and diethyldithiophosphate14,15,16,17,18,19). Although DAPs are common metabolites of OPs in general, there are some OPs, including propetamphos (PPT), that are not metabolized to DAPs. It is impossible to monitor the exposure levels of such OPs by assessing the DAPs in urine, which is a problem for the current biomonitoring.

PPT is a vinyl phosphate group-containing OP generally used in indoor residential, medical, commercial, industrial buildings and equipment, and food service establishments for controlling cockroaches, flies, ants, moths, fleas, mosquitoes, ticks, spiders, and termites in different parts of the world, including Japan20,21). PPT is also used as veterinary medicine in many countries to treat skin ectoparasites, such as cattle ticks, blowflies, lice, and keds22,23,24). The use of PPT may contaminate the surrounding environment as PPT residues have been found in environmental media24,25,26), and human populations may also be exposed to PPT through unidentified sources in the environment. Thus, human biomonitoring of urinary metabolite to evaluate PPT exposure levels is pivotal for assessing exposure from a public health perspective.

Previously, researchers in the United Kingdom conducted human volunteer studies to investigate a major metabolite of PPT and successfully detected methylethylphosphoramidothioate (MEPT) as an exposure marker of PPT for biomonitoring in human urine via gas chromatography–flame photometric detector (GC–FPD)27,28,29). One of their studies monitored urinary MEPT in PPT-exposed and unexposed workers as an application of the biomonitoring method to field surveys27). Their biomonitoring method successfully detected MEPT only in PPT-exposed workers. Biomonitoring of MEPT in urine samples from unexposed individuals is also necessary to evaluate environmental exposure levels. However, to date, no epidemiological data has been reported. Thus, a sensitive analytical method for human biomonitoring of MEPT using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) is required. Therefore, the objectives of the present study were to develop a biomonitoring method for the quantitative measurement of urinary MEPT using GC–MS and to assess urinary MEPT concentrations in both occupationally and non-occupationally exposed human populations in Japan.

Materials and Methods

Ethical permission and consent

The ethics committees of the Nagoya City University Graduate School of Medical Sciences (approval number: 70-00-0092) and Nagoya University Graduate School of Medicine (approval number: 2013-0012) in Nagoya, Japan, approved the study protocol. All participants provided written informed consents before enrolling in the study. The confidentiality and rights of the participants were strictly protected.

Chemical and reagents

The MEPT standard (analytical grade) was purchased from Hayashi Pure Chemical Industries. Ltd. (Osaka, Japan). Dibutyl phosphate (DBP, >97.0% purity; analytical grade), which was used as an internal standard (IS), was purchased from Tokyo Chemical Industries Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan). Acetonitrile (high-performance liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry [HPLC] grade), n-hexane (HPLC grade), toluene (HPLC grade), sodium chloride, sodium disulfite, potassium carbonate, and 6 mol/L hydrochloric acid were procured from Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd. (Osaka, Japan) and anhydrous sodium sulfate was procured from Kanto Chemical Co., Inc. (Tokyo, Japan). Diethyl ether and 2,3,4,5,6-pentafluorobenzyl bromide (PFBBr) (99% purity) were procured from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Ultra-pure water was used throughout the experiments and was obtained via distillation and deionization using a Millipore Milli-Q system (Millipore Co., Bedford, MA, USA).

Apparatus and GC–MS conditions

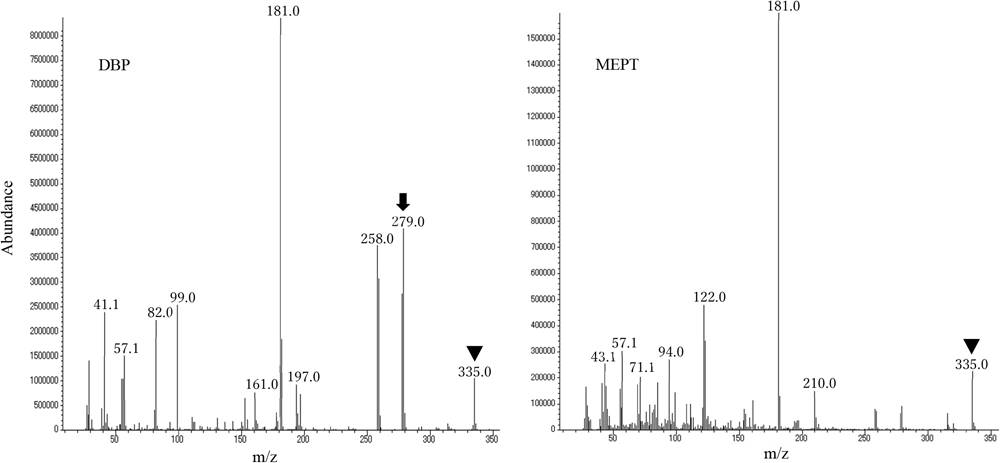

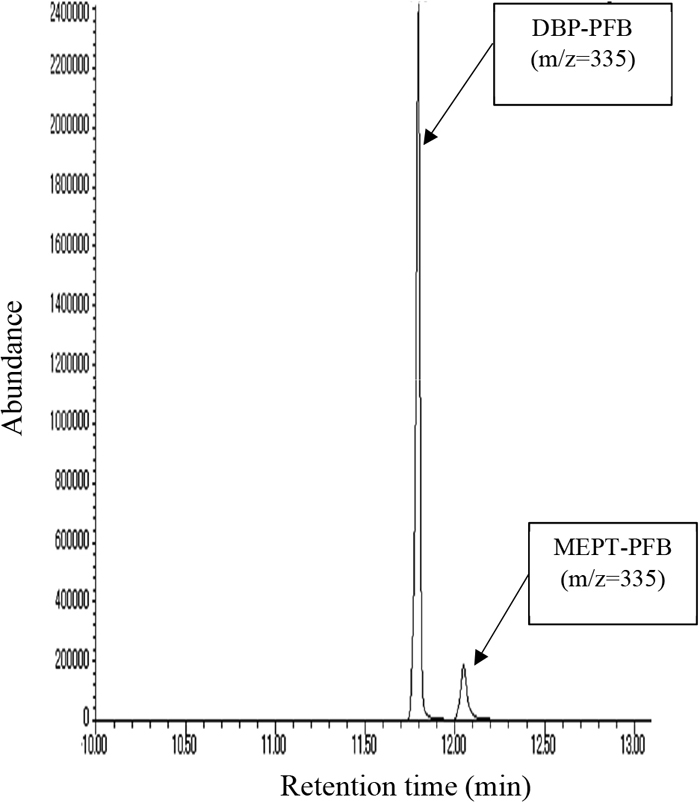

Analyses of MEPT as a PFBBr-derivative were performed using an Agilent 7890A GC-5975 inert mass selective detector (MSD) system. The GC operating conditions were as follows: column: Rtx-65 (Restek Corporation, Bellefonte, PA, USA), 30 m×0.25 mm i.d., 0.25 μm film thickness; column temperature: 70°C (1 min)–15°C/min –300°C (6 min); injection port temperature: 250°C; carrier gas: helium (99.999% purity); flow rate: 1 mL/min. The injection volume was 1 μL in the splitless mode. The temperatures of the MSD transfer line, ion source, and quadrupole were 300, 230, and 150°C, respectively. The selected ion monitoring mode was employed for MS acquisition, and the analysis mode comprised electron ionization (positive ion, 70 eV). The chromatogram peaks of the analytes were identified based on the quantification ion (Q-ion), confirmation ion (C-ion), and retention time, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Chemical structures of methylethylphosphoramidothioate (MEPT), dibutyl phosphate (DBP), and 2,3,4,5,6-pentafluorobenzyl bromide (PFBBr) derivatives of MEPT (MEPT-PFB) and DBP (DBP-PFB) and their fragment ions and retention time

NA, not available. RT, retention time.

am/z: mass to charge ratio.

bQ-ion: selected ion for quantification.

cC-ion: selected ion for confirmation.

The MEPT standard was prepared at a concentration of 1,000 mg/L in methanol, and then diluted to each working standard solution (10, 100, 500, and 1,000 μg/L) with pooled urine. The standard solutions were stored in a freezer at −80°C and were used within 1 month of preparation. For the basic methodological examinations, urine samples from 203 healthy pregnant women (a population considered to have the lowest level of PPT background exposure) were mixed and used as pooled urine. The pooled urine samples were stored at −80°C and diluted 100 times with ultra-pure water. Dilution was performed to reduce equipment contamination and matrix effects, which did not affect the analytical results.

Analytical procedure

The analytical procedure for the measurement of MEPT in human urine was developed by modifying a previously used method for the assessment of DAPs30). A mixture of 2 mL of urine, 20 μL of IS (100 mg/L DBP), 2.5 g sodium chloride, 1 mL of 6 mol/L hydrochloric acid, 50 mg of sodium disulfite, and 3 mL of diethyl etheracetonitrile (1:1, v/v) was shaken vigorously and centrifuged. Then the organic phase, passing through a 1 g anhydrous sodium sulfate-containing column, was collected into a screw-cap test tube containing 15 mg of potassium carbonate. Subsequently, the aqueous phase was re-extracted with 2 mL of diethyl ether–acetonitrile solution. The resulting extract was evaporated under a gentle nitrogen stream. In the dried extract, 15 mg of potassium carbonate, 1 mL of acetonitrile, and 10 μL of PFBBr were added and incubated with the heat block for 30 min at 80°C. Then 3 mL of water and 3 mL of n-hexane were added, shaken, and centrifuged, and the upper layer was transferred to a new glass tube. The extraction was repeated with 3 mL of n-hexane, and the extract was evaporated under a gentle nitrogen stream. Finally, the extracted compounds were dissolved in 50 μL of toluene and injected into the GC–MS equipment for analysis.

Assay validation

Using the modified method30), a calibration curve was prepared using pooled urine spiked with the standard, for determining the urinary MEPT in the study participants. The curve corresponded to concentrations of urinary MEPT ranging from 10 to 1,000 μg/L (four points). The calibration curve was based on the ratios of analyte and IS peak areas (Q-ions) relative to the nominal concentrations in the standard-spiked urine samples.

The within-run accuracies and precisions were evaluated by spiking the MEPT standards into pooled urine at concentrations of 10 and 100 μg/L (n=7, for each concentration). Consequently, the between-run accuracies and precisions were examined on seven different days with seven different runs of the pooled urine samples spiked with MEPT standards at the same concentrations (10 and 100 μg/L) as in the within-run assay.

To evaluate the recovery rate, the analyte was estimated using two different concentrations of 10 and 100 μg/L (n=7, for each concentration), and the standard was spiked with pooled urine before and after the extraction and the results were compared.

Furthermore, we investigated analyte stability in the pooled urine samples. First, the analyte stability in the standard-spiked pooled urine samples at two different concentrations (10 and 100 μg/L, n=2, for each concentration) was evaluated based on repetitive thawing (1.5 h) and storage at −80°C for 24 h (one cycle) and 48 h (two cycles) time intervals before the experimental day. The stored standard-spiked pooled urine samples were collected from the −80 ºC freezer and placed in water at room temperature for 30 min and then incubated at room temperature for 1 h after being obtained from the water. They were again stored in a freezer at −80°C for each consecutive cycle. Second, the stability of the target analytes in the prepared samples (10 and 100 μg/L, n=2, for each concentration) was evaluated immediately after preparation (0 h), and after storage for 24 h at room temperature.

A carryover test was also conducted using standard-spiked pooled urine samples. Carryover in the blank samples was assessed by injecting the blank samples, after measuring samples with analytes at a high concentration (1,000 μg/L).

Study participants and urine sample collection

A total of 110 study participants living in Aichi Prefecture (the central region of Japan) were selected for this study, including occupational PPT sprayers (n=15), non-PPT sprayers (n=15), and control subjects (n=80). All study participants were male workers, and the average ages of the PPT sprayers, non-PPT sprayers, and control study participants were 38.0 (standard deviation [SD], 11.0), 42.5 (SD, 14.8), and 41.6 (SD, 9.5) years, respectively.

Both the PPT sprayers and non-PPT sprayers were the employees of the pest control companies and were requested to provide first-morning voids during health checkups between 2017 and 2019, which were collected the day after spraying insecticides. Almost all PPT sprayers wore personal protective equipment (PPE) during spraying to avoid dermal and inhalation exposure, including general masks that could not effectively adsorb or filter insecticide vapor/mist. They sprayed PPT at different times of the day (evening, night, or midnight) for short periods of time (ranging from 0.5 h to 2 h) on the last spraying day and provided morning voids after a long elapsed time (ranging from 7 to 21.5 h). Non-PPT sprayers belonged to the same companies as the PPT sprayers, but did not spray the PPT for a month before urine sampling. We also collected first-morning void samples from control subjects who worked for a food distribution company, including drivers, office workers, section chiefs, and salesmen.

Urine samples were stored at 4°C immediately after collection and then transported to our laboratory on the same day. In the laboratory, we stored the aliquoted urine samples at −80°C until the MEPT analyses.

Determination of urinary creatinine concentrations

Creatinine concentrations in the urine of the study subjects (n=110) were measured using the LaChrom Elute System (Hitachi High-Tech Science Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) according to a reference method established by the Japanese Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards as described previously31).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the International Business Machines (IBM) Statistical Package for Social Sciences software version 26 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). When the urinary concentrations were less than the LOD, the MEPT concentrations were estimated to be the LOD value devided by the square root of 2.

Results

Assay validation

The optimized parameters and retention times of the analytes are shown in Table 1. The Q-ion selected for both MEPT and DBP was 335, whereas the C-ion selected for DBP was 279 (Table 1 and eFigure 1). We identified MEPT based on the retention time and chromatogram peak and quantified it based on the Q-ion peak area (eFigure 2). The accuracy, precision, recovery, and analyte stability of the standard-spiked pooled urine samples are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Limit of detection (LOD), accuracies, precisions, recovery rates, and stability of the analytes in the matrix

| n | Spiked concentration (μg/L) | MEPT |

|---|

| R2 of calibration line | | | ≥0.98 |

| 10–1,000 μg/L | | | |

| LOD | | | 10 μg/L |

| Within-run accuracy (% of nominal concentration) |

| 7 | 10 | 112.6 |

| 7 | 100 | 98.7 |

| Between-run accuracy (% of nominal concentration) |

| 7 | 10 | 84.5 |

| 7 | 100 | 89.5 |

| Within-run precision (% RSD) |

| 7 | 10 | 19.4 |

| 7 | 100 | 17.5 |

| Between-run precision (% RSD) |

| 7 | 10 | 10.4 |

| 7 | 100 | 18.1 |

| Recovery rate (%) |

| 7 | 10 | 106.4 |

| 7 | 100 | 85.5 |

| Analyte stability in repetitive thawing urine samples storage at −80°C (% of nominal concentration) |

| One cycle | 2 | 10 | 88.0 |

| 2 | 100 | 86.5 |

| Two cycles | 2 | 10 | 83.5 |

| 2 | 100 | 95.5 |

Stability of analyte in prepared sample (% of nominal concentration)

Hours (h) after preparation |

| 0 h | 2 | 10 | 87.9 |

| 2 | 100 | 106.3 |

| 24 h | 2 | 10 | 89.2 |

| 2 | 100 | 118.8 |

n, number of standard-spiked urine samples (replicates); RSD, relative standard deviation; MEPT, methylethylphosphoramidothioate.

The calibration curves were obtained using standard-spiked pooled urine, and the coefficient of determination for each run was ≥0.98. The lowest concentration of the standard curve (10 μg/L) was considered as the limit of detection (LOD) in the present study. The signal-to-noise ratio at 10 μg/L was 13.8.

The ranges for within-run accuracies and precisions for the MEPT were 98.7–112.6% and 17.5–19.4%, respectively. The between-run accuracies and precisions ranged from 84.5% to 89.5% and from 10.4% to 18.1%, respectively.

The recovery rates of MEPT in the 10 and 100 μg/L standard-spiked pooled urine samples were 106.4% and 85.5%, respectively.

The accuracies of the one and two freeze-thaw cycle processes for the urine samples were estimated to range from 86.5% to 88.0% and 83.5% to 95.5%, respectively. A time-course analysis of the prepared samples revealed that the results measured within 24 h were not different from those measured immediately after preparation (0 h).

In the carryover test, no analytes were detected in the blank samples after the high concentration standard (data not shown).

Urinary MEPT concentrations in spraying and non-spraying workers

We performed duplicate assays for each of the 110 urine samples, and the average concentrations of MEPT (percentage of relative standard deviation [RSD] was less than 20 for all samples) were used for the final analyses. The screening results for urinary MEPT in the three study groups are shown in Table 3. The detection rates of urinary MEPT in the occupational PPT sprayers, non-PPT sprayers, and control (environmentally exposed) subjects were 26.7%, 6.7%, and 2.5%, respectively. The seventy-fifth percentile concentrations of creatinine-unadjusted and creatinine-adjusted MEPT in the occupationally exposed participants were 14.6 μg/L and 4.5 μg/g creatinine, respectively. The ranges for creatinine-unadjusted urinary MEPT concentrations for the PPT sprayers, non-PPT sprayers, and control subjects were <LOD–22.3, <LOD–21.9, and <LOD–13.8 μg/L, and creatinine-adjusted were <LOD–12.1, <LOD–12.7 and <LOD–7.9 μg/g creatinine, respectively.

Table 3. Detection rate and number of study participants detected with MEPT, percentile concentrations, and range of MEPT among the three study groups

| Creatinine-unadjusted MEPT (μg/L) | Creatinine-adjusted MEPT (μg/g creatinine) |

|---|

| Sprayer (n=15) | Non-PPT sprayer (n=15) | Control (n=80) | Sprayer (n=15) | Non-PPT sprayer (n=15) | Control (n=80) |

|---|

| % Detected (N) | 26.7 (4) | 6.7 (1) | 2.5 (2) | | | |

| Percentile | | | | | | |

| 25th | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD* | <LOD* | <LOD* |

| 50th | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD* | <LOD* | <LOD* |

| 75th | 14.6 | <LOD | <LOD | 4.5 | <LOD* | <LOD* |

| Range | <LOD–22.3 | <LOD–21.9 | <LOD–13.8 | <LOD*–12.1 | <LOD*–12.7 | <LOD* ̶ 7.9 |

LOD, limit of detection; MEPT, methylethylphosphoramidothioate; n, number of study participants; N, number of detected study participants; PPT, Propetamphos.

* creatinine-adjusted LOD (4.47 μg/g creatinine).

Discussion

This is the first study to develop a human biomonitoring method using a GC–MS for urinary MEPT as an exposure marker of PPT. Our method successfully determined urinary MEPT concentrations in both PPT sprayers and non-sprayers in Japan. The results suggest that the PPT exposure level of occupational PPT sprayers in the involved companies was low, as MEPT was only detected in a quarter (1/4) of the sprayers.

Previously, one research group in the United Kingdom established a method for the detection of MEPT, and their technique was applied to human volunteers to whom PPT was orally and dermally administered29). Another study detected urinary MEPT in a PPT-exposed group (n=5) but did not detect it in the unexposed (control) group (n=20)27). Their method required an extra step of azeotropic distillation, whereas we developed a method that could directly derivatize MEPT without azeotropic distillation. We performed acid hydrolysis of urine samples for the deconjugation of MEPT instead of alkaline hydrolysis, which was carried out by the Unitd Kingdom researchers27,28,29). The LOD of MEPT in our method was 10 μg/L, whereas their LOD using a GC–FPD was 250 nmol/L (38.75 μg/L) at a signal-to-noise ratio of 327). Therefore, the sensitivity of our method is better compared to that of the previous method27). However, the detection rate of MEPT was still low in occupational sprayers in the present study. The possible reasons for the low metabolite levels and detection rate in the occupational PPT sprayers in our study might include wearing PPE, spraying PPT for short periods of time, and collecting first-morning voids after a long elapsed time.

This study evaluated the analyte stabilities in both pooled and prepared samples at different storage temperatures and found no decline in MEPT levels (Table 2). This finding was similar to a previous study, which reported that the stability of MEPT at room temperature (20°C), fridge (<5°C), and freezer (<−20°C) was unchanged for 43 days under all three conditions28). Furthermore, the within-run and between-run accuracies, precisions, and recovery rates were found to be within the acceptable ranges of standard analytical guidelines32,33,34). Thus, our method can be applied for the biomonitoring of urinary MEPT (≥10 μg/L) in human populations.

Initially, blood cholinesterase activity was commonly measured to assess the exposure levels and degree of toxicity induced by OPs14,35,36). Over time, researchers realized that urinary metabolites of exposed pesticides are better markers for low-level exposures than blood cholinesterase activities, owing to the higher sensitivity of urinary markers. The measurement of urinary metabolites of exposed pesticides might manifest the true degree of exposure; it is a logistically simple and noninvasive biomonitoring strategy that can detect exposure levels below the levels that inhibit acetylcholinesterase activity37,38,39). This study can measure a low concentration (10 μg/L) of urinary MEPT, but a significant effort is required to further improve the detection sensitivity.

The major strength of our study is that we measured MEPT in urine samples from occupational and non-occupational (environmental) exposures. Our quantification method is also less time-consuming than previous methods27,28,29).

This study had three major limitations that can be addressed. First, the total number of study participants in the PPT sprayers and non-PPT sprayers was small compared to the controls; these small numbers of samples might not represent the actual degree of PPT exposure in sprayers. Second, we did not follow the end-of-the-shift approach and instead collected morning voids from PPT sprayers, because the PPT spraying schedule and duration on the last spraying day varied among workers depending on their clients, which made it infeasible. Third, the urine collection year differed between the groups. However, the regulation of the use of OPs did not change over time. In future research, we will assess the environmental exposure to PPT using a better study design.

Conclusions

In the present study, we established a biomonitoring method for the quantitative measurement of urinary PPT metabolite in humans. This biomonitoring method may enable researchers to assess the urinary MEPT concentrations in both occupational and non-occupational populations. Further improvement of the analytical sensitivity is warranted.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to all study participants for their dedication and cooperation in this study. This study was funded by the Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) 16H05259 and (A) 19H01078 provided by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS).

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1. Wessels D, Barr DB, Mendola P. Use of biomarkers to indicate exposure of children to organophosphate pesticides: implications for a longitudinal study of children’s environmental health. Environ Health Perspect. 2003; 111(16): 1939-1946.

- 2. Solomon KR, Williams WM, Mackay D, Purdy J, Giddings JM, Giesy JP. Properties and uses of chlorpyrifos in the United States. Rev Environ Contam Toxicol. 2014; 231: 13-34.

- 3. Simon-Delso N, Amaral-Rogers V, Belzunces LP, et al. Systemic insecticides (neonicotinoids and fipronil): trends, uses, mode of action and metabolites. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2015; 22(1): 5-34.

- 4. Karalliedde L, Feldman S, Henry J, Marrs T. Organophosphates and Health. River Edge: World scientific publishing; 2001.

- 5. Mwila K, Burton MH, Van Dyk JS, Pletschke BI. The effect of mixtures of organophosphate and carbamate pesticides on acetylcholinesterase and application of chemometrics to identify pesticides in mixtures. Environ Monit Assess. 2013; 185(3): 2315-2327.

- 6. Hongsibsong S, Kerdnoi T, Polyiem W, Srinual N, Patarasiriwong V, Prapamontol T. Blood cholinesterase activity levels of farmers in winter and hot season of Mae Taeng District, Chiang Mai Province, Thailand. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2018; 25(8): 7129-7134.

- 7. Ross SM, McManus IC, Harrison V, Mason O. Neurobehavioral problems following low-level exposure to organophosphate pesticides: a systematic and meta-analytic review. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2013; 43(1): 21-44.

- 8. Bouchard MF, Bellinger DC, Wright RO, Weisskopf MG. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and urinary metabolites of organophosphate pesticides. Pediatrics. 2010; 125(6): e1270-e1277.

- 9. Shelton JF, Geraghty EM, Tancredi DJ, et al. Neurodevelopmental disorders and prenatal residential proximity to agricultural pesticides: the CHARGE study. Environ Health Perspect. 2014; 122(10): 1103-1109.

- 10. Peiris-John RJ, Wickremasinghe R. Impact of low-level exposure to organophosphates on human reproduction and survival. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2008; 102(3): 239-245.

- 11. Androutsopoulos VP, Hernandez AF, Liesivuori J, Tsatsakis AM. A mechanistic overview of health associated effects of low levels of organochlorine and organophosphorous pesticides. Toxicology. 2013; 307: 89-94.

- 12. Zafiropoulos A, Tsarouhas K, Tsitsimpikou C, et al. Cardiotoxicity in rabbits after a low-level exposure to diazinon, propoxur, and chlorpyrifos. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2014; 33(12): 1241-1252.

- 13. Bailey HD, Armstrong BK, de Klerk NH, et al; Aus-ALL Consortium. Exposure to professional pest control treatments and the risk of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Int J Cancer. 2011; 129(7): 1678-1688.

- 14. HSE. Biological monitoring of workers exposed to organo-phosphorus pesticides. Sudbury. Health and safety executive (HSE) books; 2000.

- 15. Cocker J, Mason HJ, Garfitt SJ, Jones K. Biological monitoring of exposure to organophosphate pesticides. Toxicol Lett. 2002; 134(1-3): 97-103.

- 16. Kavvalakis MP, Tsatsakis AM. The atlas of dialkylphosphates; assessment of cumulative human organophosphorus pesticides’ exposure. Forensic Sci Int. 2012; 218(1-3): 111-122.

- 17. Hernández AF, Lozano-Paniagua D, González-Alzaga B, et al. Biomonitoring of common organophosphate metabolites in hair and urine of children from an agricultural community. Environ Int. 2019; 131: 104997.

- 18. Oya N, Ito Y, Hioki K, et al. Quantitative analysis of organophosphate insecticide metabolites in urine extracted from disposable diapers of toddlers in Japan. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2017; 220(2 Pt A): 209-216.

- 19. van den Dries MA, Pronk A, Guxens M, et al. Determinants of organophosphate pesticide exposure in pregnant women: A population-based cohort study in the Netherlands. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2018; 221(3): 489-501.

- 20. Cooke CM, Shaw G, Lester JN, Collins CD. Determination of solid-liquid partition coefficients (K(d)) for diazinon, propetamphos and cis-permethrin: implications for sheep dip disposal. Sci Total Environ. 2004; 329(1-3): 197-213.

- 21. USEPA. US Environmental Protection Agency-reregistration eligibility decision for propetamphos. Office of prevention, pesticides and toxic substances. https://archive.epa.gov/pesticides/reregistration/web/pdf/propetamphos_red.pdf. Published July, 2006. Accessed December 16, 2020.

- 22. Bramley PS, Henderson D. Control of sheep scab and other sheep ectoparasites with propetamphos. Vet Rec. 1984; 115(18): 460-463.

- 23. Ormerod VJ, Henderson D. Propetamphos pour-on formulation for the control of lice on sheep: effect of lice on weight gain and wool production. Res Vet Sci. 1986; 40(1): 41-43.

- 24. Virtue WA, Clayton JW. Sheep dip chemicals and water pollution. Sci Total Environ. 1997; 194-195: 207-217.

- 25. Koehler PG, Moye HA. Airborne insecticide residues after broadcast application for cat flea (Siphonaptera: Pulicidae) control. J Econ Entomol. 1995; 88(6): 1684-1689.

- 26. Túri MS, Soós K, Végh E. Determination of residues of pyrethroid and organophosphorous ectoparasiticides in foods of animal origin. Acta Vet Hung. 2000; 48(2): 139-149.

- 27. Jones K, Wang G, Garfitt SJ, Cocker J; K Jones G Wang S J Garfitt J Cocker. Identification of a biomarker for propetamphos and development of a biological monitoring assay. Biomarkers. 1999; 4(5): 342-350.

- 28. Garfitt SJ, Jones K, Mason HJ, Cocker J. Development of a urinary biomarker for exposure to the organophosphate propetamphos: data from an oral and dermal human volunteer study. Biomarkers. 2002; 7(2): 113-122.

- 29. Garfitt SJ, Jones K, Mason HJ, Cocker J. Oral and dermal exposure to propetamphos: a human volunteer study. Toxicol Lett. 2002; 134(1-3): 115-118.

- 30. Ueyama J, Kamijima M, Kondo T, et al. Revised method for routine determination of urinary dialkyl phosphates using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2010; 878(17-18): 1257-1263.

- 31. Ueyama J, Harada KH, Koizumi A, et al. Temporal levels of urinary neonicotinoid and dialkylphosphate concentrations in Japanese women between 1994 and 2011. Environ Sci Technol. 2015; 49(24): 14522-14528.

- 32. Smith G. Bioanalytical method validation: notable points in the 2009 draft EMA Guideline and differences with the 2001 FDA Guidance. Bioanalysis. 2010; 2(5): 929-935.

- 33. Taverniers I, De Loose M, Van Bockstaele E. Trends in quality in the analytical laboratory. II. Analytical method validation and quality assurance. Trends Analyt Chem. 2004; 23(8): 535-552.

- 34. USFDA. Analytical procedure and methods validation for drugs and biologics. US department of health and human services, food and drug administration, center for drug evaluation and research. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/analytical-procedures-and-methods-validation-drugs-and-biologics. Publisehed July, 2015. Accessed December, 2020.

- 35. Yoshida T, Kuroki Y. Epidemiological studies of anticholinesterase pesticide poisoning in Japan. In: Satoh T, Gupta RC, eds. Anticholinesterase pesticides: metabolism, neurotoxicity and epidemiology (Page 457–462). Wiley online; 2011.

- 36. Colosio C, Vellere F, Moretto A. Epidemiological studies of anticholinesterase pesticide poisoning: global impact. In: Satoh T, Gupta RC, eds. Anticholinesterase pesticides: metabolism, neurotoxicity and epidemiology (Page 341–355). Wiley online; 2011.

- 37. Griffin P, Mason H, Heywood K, Cocker J. Oral and dermal absorption of chlorpyrifos: a human volunteer study. Occup Environ Med. 1999; 56(1): 10-13.

- 38. Nutley BP, Cocker J. Biological monitoring of workers occupationally exposed to organophosphorus pesticides. Pestic Sci. 1993; 38(4): 315-322.

- 39. Satoh T, Inayat‐Hussain SH, Kamijima M, Ueyama J. Novel biomarkers of organophosphate exposure. In: Satoh T, Gupta RC, eds. Anticholinesterase pesticides: metabolism, neurotoxicity and epidemiology (Page 289–302). Wiley online; 2011.

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5803-1534

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5803-1534

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8377-8464

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8377-8464

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1617-1595

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1617-1595

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5546-6084

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5546-6084

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0670-8790

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0670-8790