2022 Volume 62 Issue 12 Pages 2500-2510

2022 Volume 62 Issue 12 Pages 2500-2510

This study explored the possibility of using upgraded coal and coke from Indonesian lignite in the ironmaking process, specifically pulverized coal Injection (hereafter, “PCI”) coal and carbon composite pellets and carbon material (sintering binder carbon material). The study found that (1) injection of upgraded coal into the blast furnace will have the same effect as the injection of lime - heavy oil slurry into the blast furnace, the combined infusion of highly volatile matter and low ash coal, and flash pyrolysis.

(2) The sintering with lignite coke is thought to have the same effect as low temperature sintering type sintering operation. (3) The manufacture of reducing pellets using upgraded coal acts to use carbon material with high volatile matter content in the reduction of carbon composite iron.

Lignite, which is found in abundance in Indonesia, has a high moisture content and a low calorific value, and it is naturally pyrogenic. Accordingly, despite the low cost of production, it cannot be exported and has been limited to small-scale use in local thermal power generation facilities. Both Japan and Indonesia are eager to have a technology for the economical conversion of lignite to exportable energy, but as yet no commercially viable technology has been found.

Nevertheless, apart from its high moisture content, most Indonesian lignite has properties that include a low ash coal content, a low ash content melting point and high gasification reactivity. For this reason, further uses for lignite by means of co-production type lignite reforming technologies can be anticipated if these properties can be enhanced and applied.1,2)

One way of enhancing these properties is the co-production type Catalytic Hydrothermal Reaction (Cat-HTR)3,4) process of the Australian firm Licella. This process is a subcritical catalytic hydrothermal reaction technology that is similar to mild liquefaction. The solid product produced through this process (hereafter, “upgraded coal”) is a fine powder that results from lignite and water being mixed and the mixture being pulverized using a rod mill to produce a water slurry feed. Its utility when used as Pulverized Coal Injection (PCI) coal and carbon composite pellets was assessed.

For purposes of comparison, the conventional Coal Plus5) of low-temperature carbonization process by vertical shaft type co-production technology was examined. This is an indirect heating exothermic process that uses a vertical movable layer system for thermal decomposition and carbonization. The solid product produced through this process (hereafter, “lignite coke”) is granular, and its application as binder carbon material for sintered ores was assessed.

Figure 1 shows the relationship of lignite, upgraded coal and lignite coke in the coal band to the assessment targets (PC coal, conventional coke). In the case of lignite, the dehydration (H2O) reaction, de-methane (CH4) reaction and decarbonation (CO2) reaction progress as the degree of coalification increases as a result of upgrading, and H/C and O/C decrease. As a result, the upgraded coal and lignite coke in the coal band are transformed to a state near that of the existing assessment targets (PCI coal, conventional coke).

Relationship of lignite, upgraded coal and lignite coke in the coal band to assessment targets (PCI coal, coke).

Figure 2 shows the relationship between the reaction field temperature and representative temperature.

Relationship between reaction field temperature and representative temperature.

In the ironmaking process, the sole use of carbon materials such as PCI is the equivalent of decomposition combustion, and the speed of combustion is rapid and the volatile matter content is emitted all at once.

Conversely, when carbon material acts on iron ore in the form of a sintering binder (coarse-grained ore) or carbon composite reducing material (powdered ore), the reaction field temperature (speed of temperature increase) is low and volatile matter content is emitted gradually.

Accordingly, in these reaction fields, understanding the degree of conjugacy and uniqueness is crucial for applying the process to the special characteristics of Indonesian lignite (low-ash coal content, low ash content melting point, high gasification reactivity etc.).

This paper reports on the knowledge gained through a study of the potential for the use of upgraded coal and lignite coke in the ironmaking process, specifically powdered carbon material (PCI coal and carbon composite pellets) and carbon material (sintering binder carbon material).

Particular focus was given to (2) combustibility (3) gasification and (5) slag formation as technical issues6) that need to be assessed for the use of upgraded coal as PCI coal.

2.1.2. Properties of Upgraded CoalFigure 3 shows the grain size following pulverization for PCI coal and upgraded coal. Compared to (a) PCI coal, the grain size of (b) upgraded coal was smaller, and the grain size distribution is narrower.

Comparison of PCI coal and upgraded coal in terms of grain size distribution following pulverization. (Online version in color.)

Figure 4 shows the appearance of PCI coal and upgraded coal (photograph taken with an electron scanning microscope). Compared to (a) PCI coal, (b) upgraded coal has a higher degree of sphericity and more surface unevenness.

Appearance of PCI coal and upgraded coal (electron scanning microscope photograph).

Table 1 shows the composition of PCI coal and upgraded coal.Compared to PCI coal, upgraded coal is characterized by a low ash content and a low ash content melting point.

| Industrial analysis (wt%: AD) | Calorific value (kca/kg: GAD) | Fuel ratio (–) | Ash fusion temperature (°C) | Ash composition (wt%) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moisture | Ash | Volatlie | Fixed C | Soften | Melting | Flow | SiO2 | Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | CaO | |||

| PCI coal | 4.6 | 8.4 | 18.9 | 68.1 | 7640 | 3.61 | 1098 | 1478 | 1513 | 51.9 | 27.6 | 5.7 | 4.6 |

| Upgraded coal | 3.9 | 6.4 | 19.4 | 70.3 | 6970 | 3.62 | 1230 | 1240 | 1355 | 32.7 | 12.1 | 27.0 | 16.7 |

| Lignite | 6.2 | 7.5 | 43.5 | 42.8 | 5780 | 0.98 | 1360 | 1400 | 1435 | 44.0 | 27.5 | 11.6 | 7.4 |

Reactivity to CO2 was evaluated by differential thermal analysis. The emission temperature of volatile matter content from the weight decrease and the temperature at the start of gasification due to solution loss reaction were evaluated by increasing the temperature from room temperature to 1000°C at a standard 10°C/min with CO/CO2 = 2.0.

2.1.4. Assessment of Combustibility of Pulverized CoalFigure 5 shows the experimental apparatus of combustion furnace.

Experimental apparatus of combustion furnace. (Online version in color.)

Combustibility was assessed using a cylindrical and horizontal combustion furnace. Air was supplied at 250 Nl/min (1000°C) and CO was supplied at 20 Nl/min. PCI coal and upgraded coal were each supplied at 50 g/min, and combustibility was assessed by means of the combustion state, particle temperature and combustion rate, and by observations of combustion char.

2.2. Assessment of the Utility of Lignite Coke as Carbon Material for Iron Ore Sintering 2.2.1. PurposeAs the technical issues that must be assessed for the use of lignite coke as carbon material for iron ore sintering, particular focus was placed on carbon material properties (grain size and surface texture), mixed granulation properties (formation of pseudo-particles), carbon material combustion rate, and sintering structure (burning).

2.2.2. Properties of Lignite CokeThe lignite coke produced by the thermal decomposition process (Coal Plus) that is the target of the current study was manufactured by dry distillation of the lignite. The conventional coke following dry distillation and the lignite coke were pulverized and the grain size distribution (weight ratio) was adjusted to >1 mm: 40%, 1–3 mm: 30% and 3–5 mm: 30%.

Figure 6(a) shows the grain size distribution for the lignite coke and the conventional coke following dry distillation, pulverizing and grain size adjustment. The conventional coke and lignite coke were adjusted to a roughly equivalent grain size distribution. Accordingly, it is possible to evaluate lignite coke as carbon material for iron ore sintering based on the difference in carbon material properties as compared to conventional coke. As a result of the aforementioned adjustment, the grain size distribution has two with 1 mm as the branching point.

Particle size distribution.

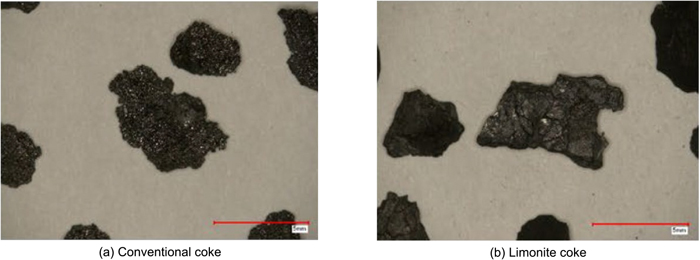

Figure 7 shows photographs of the appearance of conventional coke and lignite coke (grain size 3–5 mm). In contrast to the rounded appearance of conventional coke, lignite coke (non-caking coal with high volatile matter content) has an angular shape due to carbonization in the solid phase without melting.

Appearance of carbon material (3–5 mm). (Online version in color.)

Table 2 shows the composition of conventional coke, lignite coke and lignite for reference purposes. Due to dry distillation, the volatile matter content of lignite coke is reduced from 49.2% to 1%, and N is reduced from 1.8% to 0.7%. Conversely, the S in lignite ash is high at 3.0%, and it remains 3.0% even after dry distillation. As a result, total S increases from 0.1% to 0.2%. This is because the total S content in the lignite is almost all sulfur in ash which remains without being broken down at the temperature of dry distillation, with the result that the relative total S proportion increases due to the decrease of volatile matter content and moisture resulting from dry distillation.

| Industrial analysis (%) | Elemental analysis (%) | total-S (%) | S in ash (%) | Oxygen (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ash | Volatite | Fixed C | C | H | N | ||||

| Coke | 11.9 | 0.1 | 88.0 | 97.3 | <0.50 | 1.52 | 0.41 | 0.47 | 0.2 |

| Lignite coke | 7.3 | 1.2 | 91.5 | 98.3 | <0.50 | 0.67 | 0.21 | 2.95 | 0.5 |

| Lignite | 3.8 | 49.2 | 47.0 | 72.6 | 3.23 | 1.80 | 0.12 | 2.96 | 21.6 |

Table 3 shows the composition of iron ore and flux used for iron ore sintering.

| T-Fe | FeO | C | CaO | SiO2 | MgO | Al2O3 | P | LOI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iron ore | 64.51 | 0.19 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 1.49 | 0.04 | 1.36 | 0.066 | 3.70 |

| Lime stone | 0.140 | <0.10 | 12.25 | 55.18 | 0.14 | 0.24 | 0.04 | 0.003 | 42.97 |

| Quicklime | 0.070 | <0.10 | 0.98 | 90.46 | 0.48 | 0.36 | 0.20 | 0.009 | 6.65 |

| Dolomite | 0.212 | <0.10 | 13.00 | 30.73 | 0.50 | 20.67 | 0.19 | 0.003 | 46.37 |

| Silica stone | 2.18 | 0.49 | 0.27 | 0.45 | 86.38 | 0.53 | 3.90 | 0.029 | 1.87 |

Sintering powder for sintering with an actual machine was used as iron ore.7) Flux consisted of four items: limestone for adjusting basicity, quicklime for granulation, dolomite for use as an MgO source for the high-temperature properties of sintered ore, and silica stone for adjusting the slag quantity. The target mix was a basicity of CaO/SiO2 = 2.1, and the mix was 2.0% quicklime, 1.0% dolomite and 4.2% carbon.

2.2.4. Mixed Granulation Properties (Formation of Pseudo-particles)Each material was mixed in a concrete mixer for 40 seconds and then water was added and mixing was conducted for one minute. Subsequently, all materials were mixed in a concrete mixer for 30 seconds and the moisture content of the mixed material was checked.

For granulation, the mixed materials were placed in a drum mixer and mixed for two minutes to perform granulation. During granulation, the mixture was sprinkled with water for dilution (nozzle spray: 2.2 L/min) and the moisture content was adjusted to 7.2%.

Figure 6(b) shows the grain size distribution of the granulated material.

The grain size distribution of the granulated material for sintering is the carbon material grain size distribution shown in Fig. 6(a) with two peak distributions and 1 mm as the branching point, which has been shifted about 2 mm in the direction of the larger particle size.

Figure 8 shows a cross-section of resin-embedded granulated material.

Cross-section of granulated material.

(a) The conventional coke has a scattering of pseudo-particles, with nuclear particles measuring 1 mm or larger surrounded by adherent particles measuring 0.25 mm or less (Type C: Composite type).8,9)

(b) The lignite coke was confirmed to be particles comprising only powdered ore (Type P: Pellet type).

This is presumed to be because the grain size distribution of the pseudo-particles in Fig. 6 was narrower as compared to the conventional coke pseudo-particles.

2.2.5. Coke Combustion Behavior (Sinter Ore Firing)Figure 9 shows the experimental apparatus of sintering pot test.

Experimental apparatus of sintering pot test. (Online version in color.)

The raw material was placed in a sintering pot test unit (L265 mm×W265 mm×H590 mm) (volume 0.046 m3, ore bed thickness 580 mm, floor covering included) to intake air (1600 mmH2O (15.7 kPa)) in order to conduct sintering.

2.3. Assessment of Utility of Upgraded Coal as Carbon Material for Iron Ore Pellets 2.3.1. PurposeSince upgraded coal from lignite is a fine powder, it is expected to strengthen the bonds between particles in the agglomeration process for the iron source material for ironmaking. Moreover, as a reduction reaction occurs when the upgraded coal contained in iron ore is heated, this is expected to strengthen the metal-to-metal bonding. Accordingly, its utility as a binder for hot rolling (sintering) was assessed. Pelletizing was used as the agglomeration method for the powdered ore, and crushing strength was used as the assessment indicator.

2.3.2. Assessment of Granulation Capacity in Preparation for Producing Iron Ore PelletsTable 4 shows the composition of the raw materials for pelletizing.

| T-Fe | FeO | Fe2O3 | CaO | Al2O3 | SiO2 | MgO | SO3 | C | FC | LOI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iron ore | 66.95 | 0.16 | 95.54 | 0.03 | 0.25 | 3.88 | 0 | 0.02 | 0 | 0.24 | |

| Upgraded coal | 0 | 0 | 1.73 | 1.07 | 0.78 | 2.09 | 0.26 | 0.25 | 0 | 70.3 | 23.30 |

| Lignite | 0 | 0 | 1.55 | 0.66 | 0.40 | 1.26 | 0.50 | 0.55 | 0 | 43.4 | 51.40 |

| Portland cement | 2.03 | 0 | 2.90 | 66.57 | 4.97 | 20.56 | 1.32 | 2.94 | 0.23 | 0 | 1.56 |

Fine powder ore (hereafter, “ore”) with a small standard deviation for the degree of roughness and high water absorption was used as the iron ore for iron ore pellets. Portland cement (hereafter, “cement”) was used to adjust the basicity.

Figure 10 shows a comparison of the grain size distribution of the raw materials. A comparison with the grain size distribution of the upgraded coal mix material shows that the upgraded coal contains many more +10 μm particles that are effective for granulation than does the ore, and this was expected to improve granulation.10,11)

Raw material grain size distribution.

Iron ore pellets were created using a pan pelletizer (diameter: 40 cm), while spraying water from a vaporizer, to create pellets (hereafter, “green pellets”) with a diameter of approximately 11.2–13.2 mm, at a tilting angle of 45°C and a speed of 30 rpm.

2.3.3. Assessment of Utility as a Binder for Iron Ore Pellets for FiringFigure 11 shows the experimental apparatus of vertical electric furnace.

Experimental apparatus of vertical electric furnace.

Firing of iron ore pellets was conducted in an N2 atmosphere (3 l/min) using a vertical electric furnace under three electric furnace temperature conditions: 1050°C, 1150°C and 1250°C.

The firing method was to place a basket containing pellets in a soaking area with a descent time of 10 minutes for preheating, and then hold them there for 10 minutes of firing, and subsequently remove them from the furnace for a period of 10 minutes.

Figure 12 shows the results of differential thermal analysis. The (a) PCI coal was limited to a 21% weight reduction at 1000°C. The (b) upgraded coal exhibited a 29% weight reduction at 866°C, after which the weight reduction temperature gradient became steep and a weight reduction of 74% was observed at 1000°C.

Differential thermal analysis.

Since the volatile content was approximately 20% for both PCI coal and upgraded coal, the weight reduction for PCI coal was due to the release of volatile matter content. In the case of upgraded coal, in addition to the release of volatile content, gasification due to solution loss reaction contributed beginning at 866°C. Accordingly, upgraded coal is thought to possess high CO2 reactivity.

3.1.2. Assessment of Combustibility of Powdered CoalFigure 13 shows the temperature inside the furnace and the particle temperature during combustion. Compared to (a) PCI coal, the furnace interior and particle temperature were higher for (b) upgraded coal, and the particle temperature exceeded the ash melting point.

Temperature of oven interior and particles during firing.

Figure 14 shows a cross-section of the deposits on thermometer No. 3 that is located 150 mm from the injection point. Deposits of (a) PCI coal were uniform and the shape of the air bubbles was highly circular. Judging from the element distribution, the constituent compounds were Al2O3 and 3(SiO2) and were presumed to be an SiO2 saturable system of Mullite + SiO2.

Cross-section of deposits on thermometer.

The (b) upgraded coal had a flow structure and flat-shaped air bubbles. Judging from the element distribution, the constituent compounds were 3Al2O3·2SiO2 and were presumed to be Mullite. The phase state of the ash (solid ash, liquid ash, gaseous ash) was judged to be liquid ash.12,13,14)

Figure 15 shows the cross-sectional shape of balloon-shaped char.

Cross-section shape of char.

No major swelling from the original coal was observed for either (a) PCI coal or (b) upgraded coal.

Based on these results, the combustion rate of upgraded coal (83%) was confirmed to be higher than the combustion rate of PCI coal (79%). The difference of combustion rates are thought to be due to differences in grain size distribution and reactivity.15,16)

Accordingly, upgraded coal has higher gasification reactivity than PCI coal and is superior in terms of in-furnace consumption. Its combustibility was also judged to be good. Moreover, compared to PCI coal, upgraded coal has higher ash content basicity, and it is presumed to be good in terms of slag formation, assimilation and dripping properties as well.

3.1.3. DiscussionBased on these results, it is presumed that infusion of upgraded coal into the blast furnace will have the same effect as the injection of upgraded Brown Coal,17) or lime - heavy oil slurry18) into the blast furnace, or the combined infusion of highly volatile matter and low ash coal,19) and flash pyrolysis.20)

3.2. Assessment of the Utility of Lignite Coke as Carbon Material for Iron Ore Sintering 3.2.1. Coal Combustion Behavior (Sinter Ore Firing)Figure 16 shows the trends in the gasification index for exhaust gas and the gas use rate ηCO.

Trends in exhaust gas gasification indicator and gas utilization rate.

Compared to (a) conventional coke sintering, the increase in the gasification carbon quantity in the case of lignite coke sintering was faster, indicating that the speed of combustion was more rapid.

Conversely, compared to (a) conventional coke sintering, the gas use rate ηCO for lignite coke sintering was lower. This is thought to indicate that lignite coke had higher reactivity with CO2 as compared to conventional coke.21)

3.2.2. Sintered Ore Properties and StructureFigure 17 shows the properties of sintered ore.

Properties of sintered ore.

The (a) shatter strength and (b) rotational strength of lignite coke sintering was equal to or greater than that of conventional coke sintering.

The (c) JIS reduction index in the center was higher for lignite coke sintering than that for conventional coke sintering.

The (d) low-temperature reduction powdering rate for lignite coke sintering exhibited good properties, being lower as compared to conventional coke sintering.

Figure 18 shows the structure of the sintered ore in the center of the sintered layer. In the case of (a) conventional coke sintering, there was skeleton crystal-like hematite in the vicinity of the large pores. In the case of (b) lignite coke sintering, there was almost no skeleton crystal-like hematite, and the hematite was mottled (granular).22)

Sintered ore structure (center).

This is consistent with the finding that, in the case of this structure, the low-temperature reduction powdering rate was lower for lignite coke sintering than for conventional coke sintering, and both cold forming strength and hot forming strength were good. In the center, the JIS reduction index was higher for lignite coke sintering than for conventional coke sintering.

Judging from the above, lignite coke is presumed to have higher reactivity with CO2 than conventional coke. Moreover, based on the exhaust gas composition and sintering structure, this is thought to have the same effect as low temperature sintering type sintering operation.23)

3.3. Assessment of Utility of Upgraded Coal as Carbon Material for Iron Ore Pellets 3.3.1. Iron Ore Pellets StructureFigure 19 shows a cross-section of pellets fired at 1250°C (basic).

Cross-sectional structure of basic pellet.

The (a) upgraded coal (15%) has a delicate structure, but in the (b) lignite pellets (20%), interlocking voids can be observed.

Figure 20 shows the structure of pellets fired at 1250°C (basic).

Cross-sectional structure of basic pellet.

On the (a) upgraded coal (15%) pellets, a metallic iron network structure has formed, with scattered holes. On the (b) lignite pellets (20%), the metallic iron has not developed into a network structure, and there are voids over a wide area, with interlocking voids.

3.3.2. Iron Ore Pellets Properties (Structure Strength, Reduction Index)Figure 21 shows the relationship between crushing strength and reduction index for the acid fired pellets and basic fired pellets fired at 1250°C.

Relationship between crushing strength and reduction index when firing at 1250°C.

For the acid fired pellets, no correlation between crushing strength and reduction index was determined. For the basic fired pellets, however, there was a high correlation between crushing strength and reduction index. This is thought to be because basification produced the metallic iron network shown in Figs. 19, 20, forming a delicate structure.24,25,26,27)

3.3.3. DiscussionThe overall reduction reaction of carbon composite pellets can be expressed by the following equation.28,29,30)

| (1) |

From the carbon balance and oxygen balance in Eq. (1), Eq. (2) is obtained

| (2) |

CO gas utilization ratio: ηCO = y/(X+y)

Hydrogen utilization ratio: ηH = γ/(β+γ)

Direct reduction index: DR = X1/n

Hydrogen reduction index: DRH = α/n

Hydrogen reduction quantity: α

If the volatile content of the carbon material is limited to vaporization (α < 0), the decomposition of volatile matter can be expressed as follows:

| (3) |

If the volatile content of the carbon material extends to hydrogen emissions and carbon deposition (α > 0), the decomposition of volatile matter can be expressed as follows:

| (4) |

The reduction reaction from the interior carbon material fired at 1000°C or greater is thought to be controlled by FeO–Fe equilibrium and not Boudouard’s equilibrium.31,32) The equilibrium values for ηCO and ηH were obtained from the Fe–O–C and Fe–O–H Baur-Glaessner diagrams and the hydrogen reduction quantity α was calculated.

Figure 22 shows the relationship between the reaction hydrogen quantity and the heating temperature.

Relationship between reaction hydrogen quantity and heating temperature.

For both (a) lignite and (b) upgraded coal, the hydrogen reduction quantity α increased as the heating temperature increased. For (b) upgraded coal in particular, the reaction hydrogen quantity α became greater than zero at a heating temperature of 1250°C, and there was determined to be a possible effect from hydrogen reduction.

Based on these results, the manufacture of reducing pellets using upgraded coal acts to use carbon material with high volatile matter content in the reduction of carbon composite iron, suggesting the possibility of porous iron and steel materials.27)

Figure 23 shows the possibility and process of the use of upgraded coal and coke from lignite in the ironmaking process. In the fuel composition of carbon material consisting primarily of powdered coal and conventional coke in the ironmaking process, the carbon material acts as a sintering binder (coarse-grained ore) for the iron ore and as a pellet binder (fine-grained ore).

Possibility and process of the use of upgraded coal and coke from lignite coal in the iron making process.

In addition to the low ash content, the low ash content melting point and the high gasification reactivity of Indonesian lignite, the properties of Indonesian lignite upgraded coal were strengthened by close spacing with iron ore and rapid heating.

As a result, further use of lignite that is made possible by co-production type lignite upgrading technologies will lead to the following possibilities and uses.

(1) It is presumed that infusion of upgraded coal into the blast furnace will have the same effect as the injection of lime - heavy oil slurry into the blast furnace, the combined infusion of highly volatile matter and low ash coal, and flash pyrolysis.

(2) Based on the exhaust gas composition and sintering structure, sintering with lignite coke is thought to have the same effect as low temperature sintering type sintering operation.

(3) The manufacture of reducing pellets using upgraded coal acts to use carbon material with high volatile matter content in the reduction of carbon composite iron, suggesting the possibility of porous iron and steel materials.

This study was conducted by means of the “Study of the Possibility of Co-production Type Lignite Reforming Technology in Indonesia,” one of the “2017–2019 joint study topics relating to technical assistance projects for coal site needs, etc.” of the Japan Oil, Gas and Metals National Corporation (JOGMEC). The authors would like to express their thanks to the personnel of the JOGMEC Coal Technology Section for their outstanding support and valuable advice.