2022 Volume 62 Issue 6 Pages 1275-1282

2022 Volume 62 Issue 6 Pages 1275-1282

Microstructures and mechanical properties after spheroidizing annealing (SA) of GCr15 bearing steel with and without an alternating magnetic field (AMF) were investigated. It was found that the application of the AMF at the austenitizing stage promoted the dissolution of carbides, accelerated the austenitizing process and increased the hardness of the quenched sample. After isothermal annealing, the carbides in the sample with an AMF more uniformly distributed and became finer in comparison with those without an AMF. The average hardness of the sample treated in the AMF was lower than that without an AMF. The phenomena could be attributed to the enhanced diffusivity in the AMF.

GCr15 bearing steel has excellent mechanical properties such as high wear resistance, corrosion resistance and fatigue resistance, and thus it is widely used to manufacture the bearing ring, ball screw, bushing and other mechanical components.1,2,3) The microstructure of GCr15 bearing steel under conventional hot-rolled conditions consisted of the lamellar pearlite and a small amount of proeutectoid cementite at the grain boundaries,1,4,5) which leads to high hardness, low plasticity and poor cold workability. Therefore, the SA is routinely required to obtain superior microstructure, such as granular carbide distributed in the ferrite matrix.1,5)

However, the conventional SA process usually takes a long time of 10 to 20 h,4,6) which leads to high-energy consumption, low productivity. Therefore, some alternatives to reduce SA time have been studied, such as cyclic SA,7,8) deformation SA,6,9,10,11) online SA,12) and isothermal SA,13) etc. In addition, the aim of SA is to obtain the dispersed distribution of carbides, which is conducive to the improvement of bearing steel fatigue life,14) and there is an obvious genetic phenomenon with respect to the structures of the material during heat treatment.15,16) Up to date, how to obtain the uniform and dispersed distribution of carbides in the bearing steel is still an important topic.

Over the past decades, it has been found that the AMF can be used to modify the microstructures and properties of the metallic materials. For examples, the AMF can enhance diffusivity,17,18,19,20) refine grains,21) accelerate stress release,22) and reduce the macro/micro segregation.23,24,25,26) In the aspect of heat treatment, it was found that the AMF not only could improve the microstructures and properties of some light alloys,18,27,28) but also improve the magnetic properties of electrical steel and refine the pearlite structure.29) More recently, the AMF was applied to treat the GCr15 bearing steel at room temperature. It was found that the application of the AMF led to increase the dislocation density and to improve the strength and the wear resistance.30) Therefore, the application of the AMF provides a new idea that can be used to regulate microstructures and properties during heat treatment.

In this work, the effect of the AMF on the microstructure and performance of the GCr15 bearing steel during heat treatment was explored. It was found that the AMF promoted the dissolution of the lamellar carbides and accelerated the austenitizing process. Further, insight into the reasons have been given.

The hot-rolled GCr15 bearing steel rod with diameter of 40 mm was used and the chemical composition is shown in Table 1. The samples with dimensions of 8 × 8 × 5 mm were cut from the as-received rod and were heat treated with and without an AMF.

| C | Si | Mn | P | S | Cr | Cu | V | Al | Fe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.95 | 0.26 | 0.40 | 0.006 | 0.001 | 1.55 | 0.049 | 0.004 | 0.007 | Bal. |

The AMF was generated by water-cooling copper coils together with a 50-Hz alternating current power source. The AMF intensity could be adjusted from 0 to 0.1 T by regulating the electric current. The sample was sealed in a glass pipe during heat treatment to avoid oxidation. The sample was placed in the region where the AMF intensity was maximum and the temperature was homogeneous. The temperatures of the furnace and the sample were monitored by S-type thermocouples with an accuracy of ±1°C. The experimental apparatus for heat treatment of the GCr15 bearing steel in the AMF is shown in Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram of experimental apparatus for heat treatment of the GCr15 bearing steel in the AMF. (Online version in color.)

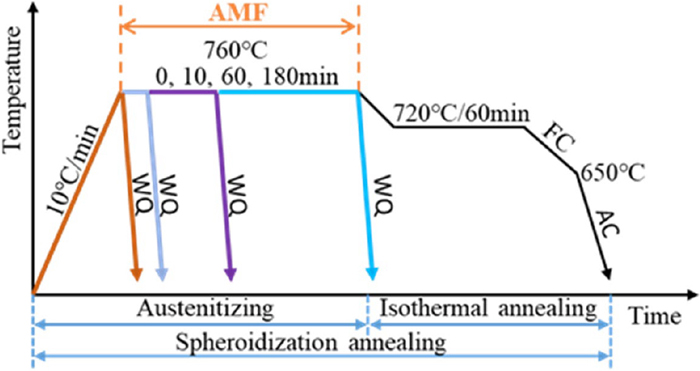

The SA heat treatment schedule for the GCr15 bearing steel, as shown in Fig. 2, includes two steps, i.e., austenitizing and isothermal annealing:

(1) Austenitizing, 760°C/0, 10, 60, 180 min.

(2) Isothermal annealing, 720°C/60 min →furnace cooling (FC) to 650°C →air cooling (AC).

SA heat treatment schedule for the GCr15 bearing steel with and without the AMF. (Online version in color.)

For comparison, a set of samples were heat treated in the AMF which was applied to the austenitizing stage at 760°C, while another set of samples were heat treated without an AMF. To compare the extent of transformation during austenitizing for different times with and without an AMF, a series of quenching experiments have been performed.

The heat-treated samples were ground, polished and etched with a mixture of 4% nitric acid and alcohol for 10–15 seconds at room temperature. The microstructures were observed by scanning electron microscope (SEM). Martensite content, carbide particle size and its distribution were measured using Image Pro Plus software. In the samples quenched after austenitizing, the martensite content was obtained based on randomly selected region in each condition. More than 3000 carbide particles were measured in the samples with the longest austenitizing holding time of 180 min after isothermal annealing. The average Rockwell C hardness was determined from five randomly selected positions of each sample. The phases in the samples were identified by X-ray diffraction (XRD). The intensity and full width at half maximum (FWHM) of XRD peaks were measured via Jade 6.0 software.

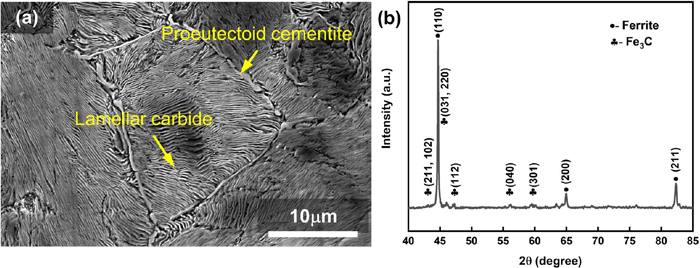

The microstructure in the as-received rod is shown in Fig. 3(a), which consists of lamellar pearlite and proeutectoid cementite. The lamellar pearlite is a mixture of ferrite (α) and cementite (Fe3C). Figure 3(b) displays the XRD pattern of the as-received sample, which confirms that the phases of the lamellar pearlite in Fig. 3(a) are ferrite and cementite.

Microstructure and XRD pattern of the as-received GCr15 bearing steel: (a) SEM micrograph, (b) XRD pattern. (Online version in color.)

As we know, when the GCr15 sample was heated to a certain temperature above the eutectoid temperature, the austenitization occurs, i.e., the lamellar pearlite is transformed into austenite (γ). The extent of transformation is dependent on temperature and holding time. The subsequent quenching leads to transformation from the austenite to martensite (α′). The amount of martensite reflects the extent of austenitization. Figure 4 shows the SEM images of microstructures in the GCr15 bearing steel quenched after austenitization for different holding times without and with an AMF. For no holding time, the microstructure of the sample quenched at 760°C (Fig. 4(a)) is almost the same as that of the as-received sample (Fig. 3(a)). That is to say, almost no austenite forms when no holding was performed during austenitizing. With extending the holding time, the proeutectoid cementite at the grain boundaries gradually dissolve and thus become shorter or even disappear. For lamellar pearlite, with the increase of the holding time, the lamellar carbides gradually transform into granular carbides (Figs. 4(b) to 4(g)). For the same holding time, the amount of the residual lamellar carbides in an AMF is less than that without an AMF. When the holding time is up to 180 min, the lamellar carbides in the AMF disappears completely, but still exists in the sample without the AMF (Figs. 4(f) and 4(g)), indicating that the AMF promotes the dissolution of carbides in the matrix.

SEM micrographs of the GCr15 bearing steel samples quenched after austenitization for different holding times without and with an AMF, (a) 0 T, 0 min, (b) 0 T, 10 min, (c) 0.1 T, 10 min, (d) 0 T, 60 min, (e) 0.1 T, 60 min, (f) 0 T, 180 min, (g) 0.1 T, 180 min. (Online version in color.)

In order to further characterize the microstructure transformation during austenitizing, XRD measurements were performed, as shown in Fig. 5. The microstructure transformation from pearlite to austenite (martensite) can clearly be observed from their changes of characteristic peaks. For the same holding time, the characteristic peaks of martensite in the sample with the AMF firstly appear (0.1 T, 10 min) and the peaks of ferrite completely disappear (0.1 T, 60 min). However, there is still a peak of ferrite for 60 min without an AMF. It follows that the AMF accelerates the transformation from pearlite to austenite, which is agreement with microstructure observation.

XRD patterns of the GCr15 bearing steel samples quenched after austenitization with and without the AMF. (Online version in color.)

In addition, the intensities and FWHMs of some peaks were compared, as shown in Fig. 6. As the holding time increases, the intensities of (110) and (211) peaks both decrease. The peaks intensities with an AMF drop more significantly for the holding time less than 60 min, and then are close to each other with and without an AMF for 180 min. The change in peak intensity accords to the extent of transformation from pearlite to austenite. That means that the AMF accelerates the transformation, and less residual ferrite leads to a weaker peak. The FWHM of the peak increase with increasing the holding time regardless of the AMF. The value of FWHM in the AMF is larger than that without AMF for the same holding time less than 60 min. The change in the FWHM also means that the more martensite, which includes defects such as dislocation or lattice distortion, forms in the sample treated in the AMF.

The intensities and FWHMs of XRD peaks with and without the AMF, (a) (110), (b) (211). (Online version in color.)

It is well known that the supersaturated solid solution of carbon in martensite causes lattice distortion and a much higher dislocation density, which broadens the peak in X-ray diffractograms.31,32,33,34) Martensite can be interpreted as ferrite with slight tetragonal distortion in crystallography,34) and the tetragonality, c/a, has a linear relationship with the carbon content ([C] in wt.%) as follows:34)

| (1) |

The amount of martensite without and with the AMF is indicated in Fig. 7. From this histogram, it can be seen that as the holding time increases, the fraction of martensite gradually increases regardless of the AMF. For the same holding time, the amount of martensite in the AMF is significantly larger in comparison with that without the AMF. The average martensite fractions in the specimens for 10, 60, and 180 min with an AMF increased from 23.9%, 55.8%, 72.7% to 46.6%, 94.8%, 100.0%, respectively. It follows that the AMF promoted the formation of austenite.

Martensite contents in the quenched samples after austenitization for different holding times without and with the AMF. (Online version in color.)

Figure 8 shows the microstructure after isothermal annealing. With the extension of holding time, the amount of lamellar carbides gradually decreased and granular carbides gradually increased. Similar to quenched microstructures, for the same holding time, the fraction of granular carbide with an AMF is more than that without an AMF (Figs. 8(b) and 8(c), 8(d) and 8(e)). When the holding time of austenite is 180 min, there are a small amount of lamellar carbides in the microstructure after isothermal annealing treatment without an AMF. In comparison, the carbides with an AMF completely become granular (Figs. 8(f) and 8(g)). During isothermal annealing, the fine carbides in austenite become the core, spheroidize and grow up. This process is called divorced eutectoid transformation (DET).1,4,37) Obviously, the application of the AMF accelerates the subsequent DET and the formation of granular carbides from the austenite, while a few lamellar carbides still exist owing to incomplete transformation in the absence of the AMF. XRD patterns of the GCr15 samples after isothermal annealing are shown in Fig. 9. After holding at 720°C for 60 min, the XRD patterns of all samples exhibit three narrow and strong peaks, corresponding to ferrite structure.

SEM micrographs of the GCr15 bearing steel samples without or with an AMF after isothermal annealing, (a) 0 T, 0 min, (b) 0 T, 10 min, (c) 0.1 T, 10 min, (d) 0 T, 60 min, (e) 0.1 T, 60 min, (f) 0 T, 180 min, (g) 0.1 T, 180 min. (Online version in color.)

XRD patterns of the GCr15 bearing steel samples after isothermal annealing. (Online version in color.)

For the samples with the holding time of 180 min at the autensiting stage, the size distribution of carbides after isothermal annealing was compared, as shown in Fig. 10. The mean diameter of carbides is about 0.35 um with the AMF, which is less than 0.39 um that without an AMF. The radius ratio (Max Diameter/Min Diameter) is used to characterize the roundness of carbide particles. The closer to unity the value of the radius ratio is, the more round the particle is. The radius ratios with or without an AMF are 1.96 and 2.13, respectively, which indicates that the carbides in the AMF have better roundness than those without an AMF. Additionally, the curves in Fig. 10 with the AMF are higher and narrower than the curves without an AMF, indicating that the carbides more uniformly distributed.

The size distribution of carbides after isothermal annealing, (a) mean diameter, (b) radius ratio (Max Diameter/Min Diameter). (Online version in color.)

The Rockwell hardness values of the GCr15 samples after quenching and isothermal annealing are shown in Fig. 11. The hardness after quenching increases with increasing the holding time at austenitizing stage (Fig. 11(a)). For the same holding time, the hardness with an AMF is higher than that without an AMF. For example, the hardness of the samples for 180 min are 64 HRC with an AMF and 59 HRC without an AMF, respectively, increase by 8.5%. The trend of the change in hardness with the holding time during isothermal annealing is opposite to that during quenching (Fig. 11(b)). When the austenitizing time is less than 10 min, the difference in hardness with and without an AMF is hardly observed. With increasing the austenitizing time, the hardness of the samples after isothermal annealing decreases. When the austenitizing time is longer than 60 min, the hardness of the sample in the AMF is lower than that without an AMF for the same austenitizing time. The reasons for the change in hardness with and without an AMF are discussed below.

Hardness of the GCr15 bearing steel samples. (a) Quenching, (b) Annealing. (Online version in color.)

At austenitizing stage, the pearlite transformed into austenite (martensite). The more the amount of martensite is, the larger the average hardness is. The hardness of the GCr15 sample can be estimated using a rule of mixtures based on the hardness of martensite and pearlite:1,38)

| (2) |

Yao et al.39) established the relationship between martensite hardness and carbon content less than 0.80 wt.%:

| (3) |

After isothermal annealing, the matrix transforms into pearlite, which consists of ferrite and cementite. The cementite in the pearlite has two morphologies: lamellar and granular, and the former has higher hardness.43) The samples heat-treated with an AMF for more than 60 min at austenitizing stage have fewer lamellar carbides (Fig. 8) and consequently lower hardness than those without an AMF. According to the DET theory, when the steel is heated into the two-phase region of γ + Fe3C, the existing fine carbide particles absorb the carbon atoms that is partitioned at the austenite/ferrite interface front to form large spherical carbides.1) At the stage of isothermal annealing, the spheroidization of carbides occurs while lamellar carbides will be retained. The samples treated with an AMF have more austenite content at the stage of austenitizing, less residual lamellar carbides and more spherical carbides after annealing, hence the hardness values after isothermal annealing is lower than those without an AMF.

Additionally, the effect of the magnetic field on phase transformation of ferromagnetic alloys should be considered. It is well known that the magnetic field can change thermodynamics, kinetics and thus microstructures of ferromagnetic alloys.44,45) In this work, the sample was heated to the temperature of 760°C for austenitization, at which ferrite (Curie temperature, TC is 770°C) is ferromagnetic, while austenite and cementite are both paramagnetic. When the transition from pearlite to austenite occurs, the magnetic field can promote the stability of ferrite, thus is not conducive to the formation of austenite, which is not reconciled with the experimental observation, since the above-mentioned results indicate that the magnetic field accelerates the transition from pearlite to austenite. Therefore, the change in the amount of austenite in the AMF should be attributed to other reasons.

As we know, the dissolution rate of lamellar pearlite is dependent on the diffusion rate of carbon atoms at the early stage, and on the diffusion of the alloying element (chromium) at the later stage.46,47) Thus, it is inferred that the difference in microstructure and properties with and without the AMF can be ascribed to the change in diffusivity under the action of the AMF. In fact, it has been reported that the AMF could promote the diffusion rate of alloying elements.17,18,19,20) The enhanced diffusivity can be attributed to the increase in dislocation density in the AMF, which originates from the magnetoplastic effect (MPE). The similar phenomena have been found in the aluminum alloys48,49,50) and the GCr15 bearing steel.30) Thus, it can be reasonably inferred that the application of the AMF led to the higher diffusivity of carbon in the GCr15 bearing steel, and accelerated diffusion-controlled austenitizing process. Consequently, the volume fraction of austenite (martensite) in the AMF and thus the average hardness of the sample in the AMF is higher than that without an AMF after quenching. The austenitizing process can also be accelerated by conventional heat treatment methods such as increasing the austenitizing temperature.46) However, the AMF has some special advantages in heat treatment, i.e., various magnetic effects such as enhanced diffusivity,17,18,19,20) magneto-plasticity effect,48,49,50) etc. In addition, lower heat treatment temperature is beneficial to reduce energy consumption. Therefore, the application of the AMF is expected to provide new ideas for the heat treatment of bearing steel.

The effect of SA in combination with an AMF on microstructures and the mechanical properties of the GCr15 bearing steel was investigated. The AMF accelerated the dissolution of carbides in the GCr15 bearing steel and promoted the austenitizing process. After isothermal annealing, the application of the AMF led to more uniformly distributed spherical carbides with smaller mean size and better roundness. The hardness of the sample in the AMF was higher after quenching, but the hardness in the AMF was lower after isothermal annealing. The experimental phenomena can be attributed to the enhanced diffusivity in the AMF, which promotes the diffusion rate of carbon atoms, and accelerates the dissolution of the carbides. Compared with the conventional heat treatment method by adjusting the temperature and holding time, the application of the AMF is expected to provide a new idea for heat treatment of the bearing steel.

This work was supported financially by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 52127807, 51690160), National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2019YFA0705303), Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Commission Grant (No. 17JC1400602).