Abstract

Aims: Critical limb ischemia (CLI) is an emerging public health threat and lacks a reliable score for predicting the outcomes. The Age, Body Mass Index, Chronic Kidney Disease, Diabetes, and Genotyping (ABCD-GENE) risk score helps identify patients with coronary artery disease who have cytochrome P450 2C19 (CYP2C19) polymorphism-related drug resistance and are at risk for cardiovascular adverse events. However, its application to CLI remains unknown. In this study, we aim to validate a modified ACD-GENE-CLI score to improve the prediction of major adverse limb events (MALEs) in patients with CLI receiving clopidogrel.

Methods: Patients with CLI receiving clopidogrel post-endovascular intervention were enrolled prospectively in two medical centers. Amputation and revascularization as MALEs were regarded as the outcomes.

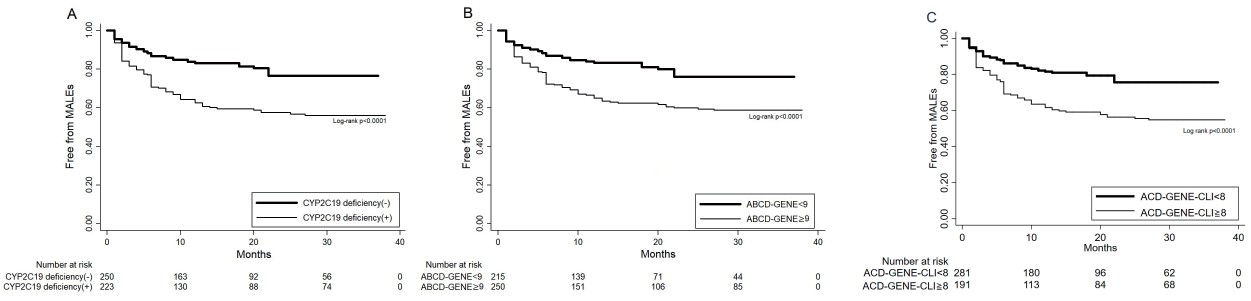

Results: A total of 473 patients were recruited, with a mean follow-up duration of 25 months. Except for obesity, old age, diabetes, chronic kidney disease (CKD), and CYP2C19 polymorphisms were significantly associated with MALEs. Using bootstrap regression analysis, we established a modified risk score (ACD-GENE-CLI) that included old age (≥ 65 years), diabetes, CKD, and CYP2C19 polymorphisms. At a cutoff value of 8, the ACD-GENE-CLI score was superior to the CYP2C19 deficiency only, and the conventional ABCD-GENE score in predicting MALEs (area under the curve: 0.69 vs. 0.59 vs. 0.67, p=0.01). The diagnostic ability of the ACD-GENE-CLI score was consistent in the external validation. Also, Kaplan–Meier curves showed that in CYP2C19 deficiency, the ABCD-GENE and ACD-GENE-CLI scores could all differentiate patients with CLI who are free from MALEs.

Conclusions: The modified ACD-GENE-CLI score could differentiate patients with CLI receiving clopidogrel who are at risk of MALEs. Further studies are required to generalize the utility of the score.

Abbreviations: ACEI/ARB: angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin Ⅱ receptor blockers; BMI: body mass index; CAD: coronary artery disease; CKD: chronic kidney disease; CYP2C19: cytochrome P450 2C19; DM: diabetes mellitus; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate; HPR: high on-treatment platelet reactivity; LDL: low-density lipoprotein; LOF: loss of function; MACEs: major adverse cardiovascular events; MALEs: major adverse limb events; CLI: critical limb ischemia

Introduction

Critical limb ischemia (CLI) is a clinical phenomenon of ischemic pain at rest or in poorly healing ulcers or gangrene, caused by peripheral artery disease (PAD)1-4). With an estimated incidence of 500–1000 million per year, it mainly occurs among elders with comorbiditiesss2). To note, CLI contributes to the rate of limb loss and amputation from 10% to 40% every year and has become an emerging public health threat1, 5). CLI management has evolved from open surgery to an endovascular approach, and the refinements in endovascular intervention have improved its outcomes6). To maintain the patency of target vessels after endovascular intervention, the use of antiplatelet drugs to suppress platelet reactivity is crucial7-9). Clopidogrel is frequently prescribed in Asians and is associated with a lower risk of gastrointestinal bleeding compared with aspirin or other P2Y12 inhibitors8, 10-12). However, loss-of-function (LOF) alleles of the cytochrome P450 2C19 (CYP2C19) enzyme are associated with a poor response to clopidogrel and result in high platelet reactivity8, 13). Compared with non-carriers, CYP2C19 LOF allele carriers, especially in Asian populations, were found to have a greater risk of adverse cardiovascular events while receiving clopidogrel for coronary artery disease (CAD)8, 13). In contrast to the relatively low prevalence (2%–5%) of CYP2C19 poor metabolizers in Caucasians and Africans, its prevalence in Asians can be up to 15%13, 14). To note, Lee et al. reported that CYP2C19 genetic profiles significantly differentiated clinical outcomes in patients with CLI receiving clopidogrel after endovascular interventions15). Thus, whether genetic testing is worthwhile for decision-making regarding drug therapy remains debatable16, 17).

The Age, Body Mass Index, Chronic Kidney Disease, Diabetes, and Genotyping (ABCD-GENE) risk score has been developed by Angiolillo et al. to assess the high on-treatment platelet reactivity (HPR) status and the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs) in patients with CAD receiving clopidogrel18). The score incorporates four clinical parameters: old age (>75 years), body mass index (BMI) >30 kg/m2, chronic kidney disease [CKD, determined as an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of <60 ml/min according to the Cockcroft–Gault formula], and diabetes mellitus (DM); and the genetic parameters of CYP2C19 LOF alleles18). Previous studies have shown that a cutoff score of ≥ 10 was sensitive in identifying patients with HPR status and was correlated with a higher risk of MACEs18). Two independent CAD cohorts in France, the Popular (Do Platelet Function Assays Predict Clinical Outcomes in Clopidogrel-Pretreated Patients Undergoing Elective PCI) and the FAST-MI (Registry of Acute ST-Elevation and Non–ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction) registries, also validated this score19, 20). However, the frequencies of CYP2C19 LOF and obesity vary between Asian and Western populations8, 13, 21). Besides, whether this score can also be applied in the risk assessment of patients with CLI remains unknown.

Thus, in the present study, we assessed the ABCD-GENE score’s ability to predict the development of major adverse limb events (MALEs) in Asian patients treated with clopidogrel after endovascular interventions. Based on the clinical and genetic parameters associated with MALEs, we optimized the score and developed a modified score with a better prediction for the risk of MALEs in the Asian population.

Material and Methods

Patients and The Study Design

We prospectively and consecutively collected clinical data and blood samples from patients with CLI who underwent endovascular interventions at two medical centers from January 2018 to December 2021. Patients with CLI who presented with rest pain, ischemic ulceration, or gangrene were classified according to the Fontaine III or IV classification2, 3). Patients should be above 20 years old and have been receiving clopidogrel for more than one year after the intervention, which included either balloon angioplasty or stenting. Patients with end-stage renal disease, a predicted lifespan of less than one year, scheduled amputation surgeries or bypass surgery, and receiving no interventions were excluded. The derivation cohort (CMMC cohort) were patients who were recruited from Chi Mei Medical Center of Tainan City, and those assigned to the validation cohort (KMUH cohort) were patients treated at Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital of Kaohsiung. The flow chart of the study design is displayed in Fig.1. Demographic data, including age, BMI, underlying diseases, biochemistry tests, Fontaine classification, locations or main lesions, types of endovascular interventions, and drug prescriptions were collected. CKD was defined as an eGFR of <60 ml/min/1.73 2, 22). DM was defined as a glycated hemoglobin of >6.5%23). As our primary outcome, MALE endpoints were defined as amputation or revascularization. The study was conducted in strict accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki on Biomedical Research involving Human Subjects and was approved by the local ethics committee (Institutional Review Board approval no. 10705-003). The enrolled patients provided written informed consent for their participation.

The blood samples were collected during endovascular interventions. Genomic DNA was isolated from the patient’s blood samples, as previously described8, 18). The TaqMan single nucleotide polymorphism genotyping assay (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) was used to measure the LOF alleles of CYP2C19*2 (681G>A; rs4244285) and CYP2C19*3 (636G>A; rs4986893) using an Applied Biosystems 7500 Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction System. Patients were classified into three genotype groups accordingly: normal metabolizers (*1/*1, no LOF allele), intermediate metabolizers (*1/*2 or *1/*3, one LOF allele), and poor metabolizers (*2/*2, *2/*3, or *3/*3, two LOF alleles).

ABCD-GENE Risk Score Modification

As previously described18), the ABCD-GENE risk score was calculated using one genetic and four clinical parameters as follows: age >75 years (4 points), obesity (BMI >30 kg/m2) (4 points), CKD (3 points), DM (3 points), one CYP2C19 LOF allele (6 points), and two LOF alleles (24 points). A cutoff score of ≥ 10 was applied to predict HPR to clopidogrel.

Statistical Analyses

Categorical variables are presented numerically and as percentages and compared using the chi-square test of heterogeneity or Fisher’s exact test. Continuous variables are presented as means with standard deviation, or median with interquartile range according to the data distribution. Comparison tests were estimated using Student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney U test. Statistical tests were 2-sided, and a p value of <0.05 indicated statistical significance. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were assessed using logistic regression. On the basis of the derivation cohort (CMMC cohort), univariate and multivariate regression analyses were performed to assess the association between key factors and MALE outcomes. Factors with a statistical significance were integrated for further score modification. Based on the selected independent risk factors, we applied a multivariate logistic regression model with 1,000 bootstrap samples to modify the score and designated it as the “ACD-GENE-CLI score.” To compare the two scores and CYP2C19 deficiency only (one allele or two alleles), receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analyses were performed based on the presence of MALEs to assess the diagnostic ability with the area under the curve (AUC) corresponding to the maximum average sensitivity and specificity. Furthermore, to evaluate the ability of the new model in correctly reclassifying and categorizing different risks, net reclassification index (NRI) was also applied24). The validation cohort (KMUH cohort) was included for external validation to ensure the generalizability of the ACD-GENE-CLI score. Subsequently, Kaplan–Meier curves were utilized to understand MALEs-free survival based on the cutoff values of the ACD-GENE-CLI scores. The best cutoff value was used for the sensitivity and specificity analysis. In addition, by separately considering the outcomes of amputation and revascularization, subgroup analyses were performed using the ACD-GENE-CLI score as either a continuous or dichotomized variable. Model 1 included all patients enrolled in the CMMC cohort. In Model 2, as a sensitivity test, we excluded patients who reached the endpoint within the first month of enrollment. Further, we performed another sensitivity test focusing on patients with or without antiplatelet agent combination therapies after endovascular interventions. Combination therapy was defined as clopidogrel plus aspirin or cilostazol for more than three months. In a sensitivity test, patients in the CMMC cohort were divided into those who received clopidogrel only and those who received a combination therapy. Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software (Version 22.0; IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

Baseline Characteristics of The Derivation (CMMC) Cohort

During the study period, 473 and 179 patients were recruited into the CMMC and KMUH cohorts, respectively. All patients received clopidogrel during the follow-up period, while the mean follow-up duration was 25 months after endovascular interventions. In the CMMC cohort (Table 1), the mean age was 66.9±13.4, with 153 (32.3%) patients who are >75 years old. Obesity was found in 13.5% of patients in this cohort. Hypertension was the most common comorbidity, and more than half of the patients have DM (53.3%) and about one-third have CKD (32.7%). In terms of endovascular interventions, half of the patients had stenotic lesions above the knee, at the level of the iliac, common femoral, and superficial femoral arteries. Around 40% of the studied population were classified at Fontaine stage Ⅳ while the rest are at Fontaine stage Ⅲ. Around 40% received stenting while the others received balloon angioplasty. Regarding the CYP2C19 allele, 47.1% of the patients had at least one LOF allele, while 11 (2.3%) patients had two LOF alleles.

Table 1.Baseline characteristics in patients with critical limb ischemia (CLI) with and without major adverse limb events (MALEs) in the CMMC cohort (N = 473)

| Variable |

All population (N= 473) |

MALE (-) (N= 334) |

MALE (+) (N= 139) |

P value*

|

| Age (y/o) |

66.9±13.4 |

66.2±12.6 |

69.1±12.8 |

0.02 |

| Age >75 y/o, n (%)

|

153 (32.3) |

100 (29.9) |

53 (38.1) |

0.05 |

| Age >65 y/o, n (%)

|

285 (60.2) |

185 (55.3) |

100 (71.9) |

0.001 |

| Men, n (%)

|

304 (64.2) |

222 (65.9) |

82 (59) |

0.14 |

| BMI (kg/m2)

|

25.1±4.7 |

25.1±4.5 |

24.5±4.7 |

0.23 |

| BMI >25 kg/m2, n (%)

|

208 (43.9) |

152 (45.5) |

56 (40.3) |

0.36 |

| BMI >30 kg/m2, n (%)

|

64 (13.5) |

47 (14.1) |

17 (12.2) |

0.35 |

| Medical history |

|

|

|

|

| Hypertension, n (%)

|

333 (70.4) |

242 (72.5) |

91 (65.4) |

0.08 |

| DM, n (%)

|

252 (53.3) |

160 (47.9) |

92 (66.2) |

0.01 |

| Hyperlipidemia, n (%)

|

286 (60.5) |

199 (59.5) |

87 (62.5) |

0.08 |

| CAD, n (%)

|

129 (27.3) |

90 (26.9) |

39 (28) |

0.8 |

| Previous stroke, n (%)

|

36 (7.6) |

27 (8.1) |

9 (6.5) |

0.69 |

| Heart failure, n (%)

|

29 (6.2) |

17 (5.1) |

12 (8.6) |

0.06 |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%)

|

61 (12.9) |

48 (14.3) |

13 (9.3) |

0.17 |

| Cancer, n (%)

|

34 (7.2) |

28 (8.3) |

6 (4.3) |

0.18 |

| Smoking, n (%)

|

320 (67.6) |

230 (68.8) |

90 (64.7) |

0.07 |

| Lab data |

|

|

|

|

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73 2)

|

53.5±40.3 |

58.6±41.7 |

42.6±35.7 |

0.007 |

| CKD (eGFR<60), n (%)

|

169 (35.7) |

205 (61.4) |

104 (74.8) |

0.006 |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dl) |

173.6±79.9 |

166.7±75.1 |

184.6±86.6 |

0.07 |

| Cholesterol (mg/dl) |

153.4±42.6 |

153.5±36.7 |

155.5±52.5 |

0.78 |

| LDL (mg/dl) |

91.5±41.8 |

91.6±36.4 |

93.5±50.2 |

0.80 |

| Triglyceride (mg/dl) |

165.1±209.9 |

175.7±229.8 |

126.1±43.3 |

0.16 |

| Endovascular angiography and interventions |

|

|

|

|

| Location (above knee), n (%)

|

259 (54.7) |

176 (52.7) |

83 (59.7) |

0.18 |

| Stenting, n (%)

|

192 (40.6) |

130 (38.9) |

62 (44.6) |

0.26 |

| Fontaine stage Ⅳ |

186 (39.3) |

123 (36.8) |

63 (45.3) |

0.09 |

| Cardiovascular drugs |

|

|

|

|

| Aspirin, n (%)

|

80 (16.9) |

54 (16.2) |

26 (18.7) |

0.66 |

| Cilostazol, n (%)

|

45 (9.5) |

26 (7.8) |

19 (13.6) |

0.56 |

| ACEIs/ARBs, n (%)

|

228 (48.2) |

167 (50) |

61 (43.8) |

0.26 |

| Statins, n (%)

|

257 (54.3) |

188 (56.3) |

69 (49.6) |

0.22 |

| CYP2C19*2 alleles

|

|

|

|

|

| None, n (%)

|

250 (52.9) |

203 (60.8) |

47 (33.8) |

0.001 |

| One allele LOF, n (%)

|

212 (44.8) |

129 (38.6) |

83 (59.7) |

0.001 |

| Two alleles LOF, n (%)

|

11 (2.3) |

2 (0.6) |

9 (6.5) |

0.001 |

*P value represents for the comparison between MALE(-) and MALE (+)

DM= diabetes mellitus; CAD= coronary arterial disease; eGFR= estimated glomerular filtration rate; CKD= chronic kidney disease; LDL= low- density lipoprotein; ACEI/ARB= angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin Ⅱ receptor blockers; LOF=loss of function

In the cohort, 29.4% (139/473) of the patients developed MALEs, with 80 patients receiving revascularization and 59 patients having an amputation. In comparison with those who were free from MALEs, the average age of patients who developed MALEs was greater (69.1±12.8 vs. 66.2±12.6 years, p=0.02; Table 1). In addition, patients with CLI who developed MALEs presented with more underlying DM (66.2% vs. 47.9%, p=0.01) and CKD (74.8% vs. 61.4%, p<0.01). Conversely, obesity, hypertension, CAD, smoking, and concomitant use of other cardiovascular drugs, including aspirin, cilostazol, anticoagulants, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers, and statins, were not significantly different between the two groups. Concerning genetic polymorphisms, the CYP2C19 LOF allele was significantly associated with developing MALEs. The majority (66.2%) of patients who developed MALEs had at least one LOF allele, compared with 39.2% of those free from MALEs (p<0.01). The distribution of the ABCD-GENE scores are presented in the bar charts in Fig.2A. As the scores increased, more patients developed MALEs. When the score exceeded 10, more than half of the patients reached the endpoint.

Logistic regression analysis revealed that CKD (OR: 1.88, 95% CI: 1.21–2.93, p=0.005), DM (OR: 2.14, 95% CI: 1.42–3.2, p=0.001), and the CYP2C19 LOF allele (one allele, OR: 2.35, 95% CI: 1.57–3.52, p=0.001; two alleles, OR: 11.49, 95% CI: 2.4–53.9, p=0.002) were significantly associated with MALE outcomes (Table 2). Notably, old age at the cutoff value of 65 years (OR: 2.08, 95% CI: 1.35–3.19, p=0.001) instead of 75 years (OR: 1.44, 95% CI: 0.95–2.19, p=0.08) specifically correlated with MALEs. Obesity, which was included in the original ABCD-GENE scores, failed to show a significant association with MALEs. Similarly, in the multivariable analysis, >65 years of age (OR: 1.94, 95% CI: 1.19–3.17, p=0.008), CKD (OR: 1.25, 95% CI: 1.03–2.1, p=0.040), DM (OR: 1.17, 95% CI: 1.01–1.73, p=0.020), and the CYP2C19 LOF allele (one allele, OR: 2.74, 95% CI: 1.78–4.21, p=0.001; two alleles, OR:20.42, 95% CI:4.21–90.8, p=0.001) were still significantly associated with the development of MALEs.

Table 2.The univariate and multivariable logistic regression analyses of clinical and genetic risk parameters in predicting MALEs in CMMC cohort

| Parameters |

Univariate analysis |

Multivariable analysis |

| Odds ratio |

95% CI |

p value

|

Odds ratio |

95% CI |

p value

|

| Age >75 y/o |

1.44 |

0.95-2.19 |

0.08 |

|

|

|

| Age >65 y/o |

2.08 |

1.35-3.19 |

0.001 |

1.94 |

1.19-3.17 |

0.008 |

| Obesity (BMI>30) |

0.85 |

0.4-1.5 |

0.59 |

|

|

|

| CKD |

1.88 |

1.21-2.93 |

0.005 |

1.25 |

1.03-2.1 |

0.040 |

| Diabetes |

2.14 |

1.42-3.2 |

0.001 |

1.17 |

1.01-1.73 |

0.020 |

| One allele |

2.35 |

1.57-3.52 |

0.001 |

2.74 |

1.78-4.21 |

0.001 |

| Two alleles |

11.49 |

2.4-53.9 |

0.002 |

20.42 |

4.21-90.8 |

0.001 |

Abbreviations as listed in Table 1

Given the differences between MALE-associated risk parameters in the present CMMC cohort compared with the ABCD-GENE scores, we used the bootstrap regression analysis to establish a modified risk score, designated as ACD-GENE-CLI. As shown in the analysis in Table 3, each of the variables was assigned an integer weighted score of 1.5 proportional to the OR for the development of MALEs. The integer points assigned included age >65 years (+3 points), CKD (+3 points), DM (+3 points), and CYP2C19 polymorphism (one LOF allele +5 points; two LOF alleles +10 points). Compared with the distribution of the ABCD-GENE scores in case numbers and the percentage of MALEs in patients with CLI (Fig.2A), the distribution of the ACD-GENE-CLI scores showed a more positive correlation between the score and the percentage of MALEs (Fig.2B).

Table 3.The Bootstrap Regression derived points in ACD-GENE-CLI score

| Parameters |

Bootstrap Regression |

Integer points assigned |

| Odds ratio |

95% CI |

P value

|

| Clinical factors |

|

|

|

|

| Old age (>65 y/o) |

2.04 |

1.10-3.55 |

0.022 |

+3 |

| CKD (eGFR<60) |

1.93 |

1.19-3.12 |

0.006 |

+3 |

| Diabetes |

1.89 |

1.12-3.03 |

0.016 |

+3 |

| Genetic factors |

|

|

|

|

| One allele |

3.69 |

1.57-4.50 |

<0.001 |

+5 |

| Two alleles |

6.89 |

5.29-19.26 |

<0.001 |

+10 |

Abbreviations as listed in Table 1

A logistic regression analysis was performed to examine the efficacy of CYP2C19 deficiency (one allele or two alleles) and the scores in predicting MALEs. Only CYP2C19 deficiency was positively associated with MALEs (OR: 1.07, 95% CI: 1.03–1.17, p=0.001). Likewise, both scores also correlated with the outcomes: ABCD-GENE score, OR: 1.13, 95% CI: 1.08–1.17, p=0.001; ACD-GENE-CLI score, OR: 1.2, 95% CI: 1.13–1.26, p=0.001 (Table 4). Even though using the previously validated cutoff value of 10 in the ABCD-GENE score could differentiate patients at risk for MALEs (OR: 2.44, 95% CI: 1.62–3.68, p=0.001), it was shown that an ACD-GENE score of ≥ 9 was more sensitive in correlating with the risks of MALEs in our study (OR: 2.77, 95% CI: 1.81–4.25, p=0.001). Further, using a cutoff value of 8 (the median value in the ACD-GENE-CLI score), patients who had the highest risk of MALEs scored ≥ 8 (OR: 3.92, 95% CI: 2.52–6.08, p=0.001). In the ROC curve analyses shown in Fig.3A, compared with the CYP2C19 deficiency and ABCD-GENE score, the ACD-GENE-CLI score was more significantly associated with MALEs (AUC 0.69 vs. 0.59 vs. 0.67, p=0.01). If we merely compared the ACD-GENE-CLI score with the conventional ABCD-GENE score, the difference was not significant (p=0.08). However, as we reclassified the population according to those with MALEs (n=139) and those without MALEs (n=334), NRI was calculated as 16.5% and significantly differentiated the risks of MALEs in comparison with the ACD-GENE-CLI and ABCD-GENE scores (pp<0.001). Further, using ACD-GENE-CLI score ≥ 8, the sensitivity and specificity are above 60%, with a less positive predictive value specificity (45.8%, 95% CI: 38.7%–53.2%) but a better negative predictive value (82.1%, 95% CI: 77.1%–86.4%) (Supplemental Table 3). Nevertheless, the accuracy statistics of the score was superior to those using only CYP2C19 deficiency or the ABCD-GENE score. Further, as shown in Fig.4, CYP2C19 deficiency and the ABCD-GENE (using a cutoff value of 9) and ACD-GENE-CLI (using a cutoff value of 8) scores could all sensitively differentiate patients with CLI free from MALEs in the Kaplan–Meier plotter.

Table 4.The logistic regression analyses of

CYP2C19 deficiency, ABCD-GENE and ACD-GENE-CLI scores associated with the development of MALEs

| Parameters |

Logistic regression analysis |

| Odds ratio |

95% CI |

p value

|

| CYP2C19 deficiency

|

1.07 |

1.03-1.17 |

0.001 |

| ABCD-GENE |

1.13 |

1.08-1.17 |

0.001 |

| ABCD-GENE ≥ 8 |

2.77 |

1.81-4.25 |

0.001 |

| ABCD-GENE ≥ 9 |

2.79 |

1.82-4.27 |

0.001 |

| ABCD-GENE ≥ 10 |

2.44 |

1.62-3.68 |

0.001 |

| ACD-GENE-PAD |

1.2 |

1.13-1.26 |

0.001 |

| ACD-GENE-CLI ≥ 7 |

3.56 |

2.26-5.61 |

0.001 |

| ACD-GENE-CLI ≥ 8 |

3.92 |

2.52-6.08 |

0.001 |

| ACD-GENE-CLI ≥ 9 |

2.79 |

1.84-4.23 |

0.001 |

Abbreviations as listed in Table 1

Supplemental Table 3.Statistics of

CYP2C19 deficiency, ABCD-GENE (using a cut-off value of 9) and ACD-GENE-CLI score (using a cut-off value of 8) in CMMC cohort

|

CYP2C19 deficiency (+)

|

ABCD-GENE (≥ 9) |

ACD-GENE-CLI(≥ 8) |

| Value |

95% CI |

Value |

95% CI |

Value |

95% CI |

| Sensitivity |

59.7% |

51.1% to 67.9% |

66.2% |

57.7% to 73.9% |

64.0% |

55.5% to 71.9% |

| Specificity |

58.1% |

52.6% to 63.4% |

52.4% |

46.9% to 57.9% |

68.6% |

63.3% to 73.5% |

| Positive Likelihood Ratio |

1.42 |

1.18 to 1.72 |

1.39 |

1.18 to 1.64 |

2.04 |

1.66 to 2.49 |

| Negative Likelihood Ratio |

0.69 |

0.56 to 0.87 |

0.65 |

0.50 to 0.83 |

0.52 |

0.42 to 0.66 |

| Positive predictive value |

37.2% |

30.9% to 43.9% |

36.7% |

30.7% to 42.9% |

45.8% |

38.7% to 53.2% |

| Negative predictive value |

77.6% |

71.9% to 82.6% |

78.8% |

72.9% to 84.0% |

82.1% |

77.1% to 86.4% |

| Accuracy |

58.6% |

53.9% to 63.0% |

56.5% |

51.9% to 60.9% |

67.2% |

62.8% to 71.5% |

To further examine whether the ACD-GENE-CLI score is applicable to other populations with CLI, we included an external cohort with 179 patients from KMUH. Compared with the CMMC cohort, the patients in the KMUH cohort were relatively older (65.9±13.4 vs. 69.1±11.3 years, p=0.06) and predominantly female (Table 1 and Supplemental Table 1). More patients in this cohort have DM (53.3% vs. 67%, p=0.001) and low eGFR (58.5±40.3 vs. 36.8±36.8 ml/min/1.73m2, p=0.001). However, fewer patients in the KMUH cohort received angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, or statins. In terms of the CYP2C19 LOF allele, more patients in the KMUH cohort presented with at least one LOF allele than those in the CMMC cohort (54.2% vs. 47.1%). Among the 179 patients, 27.3% developed MALEs during follow-up. Similarly, patients with MALEs had a higher ratio of underlying DM, CKD, and the CYP2C19 LOF allele (Supplemental Table 1). In this cohort, obesity also failed to differentiate between patients with or without the development of MALEs.

Supplemental Table 1.Baseline characteristics in patients with critical limb ischemia (CLI) with and without major adverse limb events (MALE) in validation cohort of KMUH cohort (N = 179)

| Variable |

All population (N= 179) |

MALE (-) (N= 130) |

MALE (+) (N= 49) |

P value

|

| Age (y/o) |

69.1±11.3 |

68.5±11.1 |

70.2±11.9 |

0.51 |

| Age >75 y/o, n (%)

|

64 (35.7) |

42 (32.3) |

22 (44.9) |

0.16 |

| Age >65 y/o, n (%)

|

122 (68.2) |

85 (65.3) |

37 (75.5) |

0.05 |

| Men, n (%)

|

84 (41.3) |

51 (39.2) |

23 (46.9) |

0.39 |

| BMI (kg/M2) |

24.5±4.3 |

24.6±4.3 |

24.3±4.5 |

0.58 |

| BMI >25, n (%)

|

68 (37.9) |

52 (40) |

16 (32.6) |

0.39 |

| BMI >30, n (%)

|

17 (9.5) |

13 (10) |

4 (8.1) |

0.47 |

| Medical history |

|

|

|

|

| Hypertension, n (%)

|

138 (77.1) |

103 (79.2) |

35 (71.4) |

0.32 |

| Diabetes, n (%)

|

120 (67) |

82 (63.1) |

38 (77.5) |

0.04 |

| Hyperlipidemia, n (%)

|

12 (6.7) |

12 (9.2) |

0 (0) |

0.69 |

| CAD, n (%)

|

15 (8.4) |

11 (8.4) |

4 (8.1) |

0.37 |

| Previous stroke, n (%)

|

2 (1.1) |

2 (1.5) |

0 (0) |

0.67 |

| HF, n (%)

|

3 (1.6) |

1 (0.7) |

2 (4) |

0.17 |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%)

|

27 (15) |

23 (17.7) |

4 (8.2) |

0.16 |

| Cancer, n (%)

|

15 (8.4) |

12 (9.2) |

3 (6.1) |

0.76 |

| Smoking, n (%)

|

32 (17.8) |

93 (71.5) |

32 (65.3) |

0.06 |

| Lab data |

|

|

|

|

| eGFR(ml/min/1.73 2) |

36.8±36.8 |

38.6±38.5 |

33.2±22.3 |

0.04 |

| CKD (eGFR <60) , n (%)

|

140 (78.2) |

100 (76.9) |

40 (81.6) |

0.54 |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dl) |

175.1±81.2 |

158.3±67.9 |

129.7±49.1 |

0.4 |

| Cholesterol (mg/dl) |

159.3±28.7 |

136.6±56.7 |

189±25.4 |

0.48 |

| LDL (mg/dl) |

96.9±24.9 |

93.1±24.2 |

124 ±7.1 |

0.17 |

| TG (mg/dl) |

142.8±56.2 |

154±27.3 |

186.3±21.5 |

0.24 |

| Cardiovascular drugs |

|

|

|

|

| Aspirin, n (%)

|

59 (32.9) |

49 (37.6) |

10 (20.4) |

0.54 |

| Cilostazol, n (%)

|

59 (32.9) |

46 (35.3) |

13 (26.5) |

0.11 |

| ACEI/ARB, n (%)

|

67 (37.4) |

48 (36.9) |

19 (38.7) |

0.86 |

| Statins, n (%)

|

78 (43.5) |

55 (42.3) |

23 (46.9) |

0.61 |

| CYP2C19*2 allele

|

|

|

|

|

| None, n (%)

|

82 (45.8) |

66 (50.7) |

16 (32.6) |

0.001 |

| One allele, n (%)

|

94 (52.5) |

64 (50) |

30 (61.2) |

0.04 |

| Two alleles, n (%)

|

3 (1.7) |

0 (0) |

3 (6.1) |

0.02 |

Abbreviation as listed in Table 1

As a result, the patients from the KMUH cohort had higher ABCD-GENE and ACD-GENE-CLI scores (Supplemental Table 2). Notably, despite certain differences in characteristics between the two cohorts, the ACD-GENE-CLI score was superior in predicting MALEs compared with CYP2C19 deficiency and the ABCD-GENE score (AUC 0.63 vs. 0.53 vs. 0.60, p=0.02) (Fig.3B).

Supplemental Table 2.The comparison of risk scores and outcomes in patients with critical limb ischemia (CLI) in the derivate (CMMC) and the validation (KMUH) cohorts

| Variable |

CMMC (N= 473) |

KMUH (N= 179) |

P value

|

| Risk scores |

|

|

|

| ABCD-GENE (IQR) |

9 (6, 12) |

10 (6, 13) |

|

| ABCD-GENE ≥ 9, n (%) |

250 (52.8) |

113 (63.1) |

0.02 |

| ABCD-GENE-CLI (IQR) |

8 (6, 11) |

9 (6, 14) |

|

| ABCD-GENE-CLI ≥ 8, n (%)

|

248 (52.4) |

124 (69.2) |

0.001 |

| Outcomes |

|

|

|

| MALEs, n (%)

|

139 (29.3) |

49 (27.3) |

0.69 |

| Time to events (IQR) |

8 (2, 15) |

6 (2, 25) |

|

| Amputation, n (%)

|

59 (12.4) |

17 (9.5) |

0.3 |

| Time to events (IQR) |

8 (2, 15) |

6 (2, 18) |

|

| Revasculization, n (%)

|

80 (16.9) |

32 (17.8) |

0.73 |

| Time to events (IQR) |

6 (2, 8) |

8 (6, 25) |

|

Abbreviation as listed in Table 1

Subgroup analyses were performed to separately assess the outcomes of amputation and revascularization (Fig.5). In Model 1, whether the ACD-GENE-CLI scores were set as a continuous or dichotomized variable (<8 or ≥ 8), patients who had higher scores had a significantly higher hazard ratio (HR) for amputation (Fig.5A, B). Regarding the outcome of revascularization, trends of increasing risks in patients with higher scores were evident but were not statistically significant. As a sensitivity analysis, in Model 2, we excluded patients who reached the endpoint within the first month of enrollment to avoid the influence of management during the initial period after endovascular interventions. Similarly, we observed that the higher the ACD-GENE-CLI scores, the higher the risk of amputation, revascularization, and composite endpoints of MALEs in the studied patients (Fig.5C, D).

A Sensitivity Test Focusing on Patients with or without Combination Therapies of Antiplatelet Agents

For the second sensitivity test, given that clopidogrel has been prescribed alone or in a combination with other antiplatelet agents such as aspirin after the endovascular intervention, we further investigated whether the ACD-GENE-CLI score is applicable in patients who received different types of therapies. We divided the patients according to those who are receiving clopidogrel only (n=368) and those receiving a combination therapy (clopidogrel plus aspirin or cilostazol, n=105). Noteworthily, in both sets, an ACD-GENE-CLI score of ≥ 8 was still specifically associated with MALEs (clopidogrel only: OR: 2.60, 95% CI: 1.60–4.21, p=0.001, combination therapy: OR: 3.56, 95% CI: 1.41–9.01, p=0.007) (Supplemental Table 4).

Supplemental Table 4.The logistic regression analyses of ABCD-GENE-CLI scores associated with the development of MALEs in patients with Clopidogrel use only (N = 368) or Clopidogrel combination use (N = 105)

| Parameters |

Logistic regression analysis |

| Odds ratio |

95% CI |

P value

|

| Clopidogrel use only |

|

|

|

| ABCD-GENE-CLI ≥ 8 |

2.60 |

1.60-4.21 |

0.001 |

| Clopidogrel combination use |

|

|

|

| ABCD-GENE-CLI ≥ 8 |

3.56 |

1.41-9.01 |

0.007 |

Discussion

In conjunction with clinical parameters and CYP2C19 polymorphism, the ABCD-GENE score was developed as a simple tool to identify patients with CAD who are at increased risk for adverse ischemic events21). Nevertheless, whether it could also be applied in patients with CLI remains unknown. In this Asian cohort, we found that although old age, diabetes, CKD, and CYP2C19 polymorphisms, which were included in the ABCD-GENE score, were also positively associated with MALEs, obesity was not. Instead, we developed ACD-GENE-CLI, a modified score that included old age (≥ 65 years), diabetes, CKD, and CYP2C19 polymorphisms, to predict the risk of MALEs in patients with CLI receiving clopidogrel. A cutoff value of ≥ 8 was adopted, and it presented with good accuracy in both the derivation and validation cohorts. Our findings also support that combining clinical risks and genetic testing appears helpful in stratifying the risk for MALEs in patients with CLI receiving clopidogrel (Fig.6).

This is the first study applying a modified score to predict MALEs in patients with CLI based on the ABCD-GENE score. Although several studies have attempted to validate its efficiency in different cohorts, the score was applied primarily in patients with CAD. In The Tailored Antiplatelet Initiation to Lessen Outcomes Due to Decreased Clopidogrel Response after Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (TAILOR-PCI) trial, Capodanno et al. reported that among 3,883 patients with CAD treated with clopidogrel, MACEs at 12 months were significantly increased in patients with high ABCD-GENE scores25). In another multi-site and real-world investigation focusing on patients who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention, the risk for MACEs was also higher among patients with ABCD-GENE scores greater than 10 26). In terms of the high prevalence of CYP2C19 LOF alleles in Asia, a Japanese cohort pooled from four prospective studies found that, even with a high proportion (60%) of HPR on clopidogrel, the ABCD-GENE score has a significant and moderate diagnostic ability in predicting HPR status in the population21). In addition to its feasibility in CAD, in The Clopidogrel With Aspirin in Acute Minor Stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack (CHANCE) trial focusing on patients with acute non-disabling cerebrovascular events, Dai et al. also found that the efficacy of clopidogrel–aspirin therapy decreased in patients with higher ABCD-GENE scores27). Nevertheless, in a Chinese cohort including patients with acute coronary syndrome, Wu et al. established a novel GeneFA score that only included the CYP2C19 genotype, fibrinogen, and age28). The authors found that, compared with the ABCD-GENE score, the GeneFA score presented a better predictive value for HPR in these patients28).

Noteworthily, our study found that obesity failed to differentiate the risk of MALEs in patients with CLI, and the simplified ACD-GENE-CLI score precisely reflects the outcomes. Different from western countries, patients having ischemic events in Asia usually presented with a paradoxical phenomenon of BMI. FOCUS registry (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT 00868829), a large-scale, prospective study consisting of 5,084 patients, indicated an inverse association between BMI and long-term prognosis in Asian patients with CAD29). Likewise, in a retrospective cohort study in South Korea, it was observed that compared with normal weight, obesity was more likely to reduce mortality risk in patients with ischemic stroke, especially the elderly30). In another Asian cohort, Chen et al. highlighted a U-shaped association between BMI and death from overall cardiovascular diseases31). Therefore, BMI may not be an ideal parameter to reflect the risks of cardiovascular morbidity in patients with ischemic events such as CLI.

Regarding the impact of genetic polymorphisms, unlike monogenic vascular syndromes, CLI usually results from hundreds of genes interacting with the environment9, 32). Despite the current immature state of genetic screening to assess the outcomes of CLI, scientists still attempt to investigate the applicability of genetic testing in risk stratification and prognostication9, 32). In a retrospective study, Lee et al. reported that the CYP2C19 polymorphism is associated with higher amputation rates among patients with CLI treated with clopidogrel15). Similarly, Gou et al. described that CYP2C19 LOF allele carriers have a greater risk of in-stent restenosis after endovascular treatment for CLI33). In a systematic review focusing on CYP2C19 polymorphisms in patients with CLI, Osnabrugge et al. reported an association between CYP2C19 LOF alleles and reduced clopidogrel function34). The authors suggested that CYP2C19 testing is necessary for patients with CLI receiving clopidogrel to improve the prediction of clinical outcomes34). However, in the double-blind, multicenter, randomized EUCLID trial, patients with symptomatic CLI were randomly assigned to receive ticagrelor (90 mg twice daily) or clopidogrel (75 mg twice daily)35). Although 59% of clopidogrel users harbored a CYP2C19 polymorphism, the risk of major adverse cardiac or bleeding events was similar to that of non-carriers35). Based on the collective evidence, a de-escalation-guided strategy merely accounting for the CYP2C19 LOF alleles may not be adequate to predict the MALE outcomes in patients with CLI. The newly modified ACD-GENE-CLI score integrates both clinical and genetic parameters to provide specific weight of the individual variables. Further research, including a cost-effectiveness study, is necessary to investigate the feasibility and applicability of the test for CYP2C19 polymorphism in clinical situations.

Limitations

Despite the good accuracy of the newly established score, this study still had some limitations. First, given that only Asians were included, the prevalence of CYP2C19 LOF alleles was higher than that reported in other studies. The findings highlight the complexity of multiple comorbidities and genetic polymorphisms in Asian patients with CLI. Another limitation is the lack of HPR measurements. Although tailored antiplatelet therapy based on HPR has been previously discussed, the application of platelet reactivity testing in CLI remains inconclusive36, 37). In contrast to the dynamic changes in platelet reactivity, CYP2C19 LOF alleles could guide decision-making regarding antiplatelet agents and improve clinical outcomes. Second, the newly modified score is based on the ABCD-GENE score. Since many unidentified confounding factors might interfere with the outcome in patients with either CAD or CLI, the sensitivity and specificity of the scoring system might not be adequate to identify all patients with risks. Also, if we compared the predictive power for MALEs between the ACD-GENE-CLI score with the conventional ABCD-GENE score, the results in the ROC curves showed that the difference was not statistically significant (p=0.08). However, using NRI to reclassify the populations according to the MALE outcomes , the ACD-GENE-CLI score significantly differentiated the risks compared with the ABCD-GENE score. It implied that further verification is required to test whether the ACD-GENE-CLI score could replace the ABCD-GENE score. Third, different from CAD, CLI includes a wide variety of clinical presentation and morphology, which impact the outcomes, especially MALEs. Lastly, a sample size of 473 in the derivation cohort might be too small to make the conclusion. Further studies with larger sample sizes are needed to improve the generalizability and enhance the robustness of applying prediction scores in clinical situations.

Conclusions

By studying the genetic polymorphism and clinical outcomes of patients with CLI receiving clopidogrel, we established a modified risk score, ACD-GENE-CLI that included old age (>65 years), DM, CKD, and the CYP2C19 LOF allele and compared it with the ABCD-GENE score. In the external validation cohort, the ACD-GENE-CLI score also demonstrated the ability to differentiate patients at risk for MALEs. Further studies are required to validate the feasibility of the score and to generalize its application in patients with CLI.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Funding

This study was supported by Chi Mei Medical Center and Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital. Wei-Ting Chang is receiving grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST 109-2326-B-384-001-MY3) and the National Health Research Institute (NHRI-EX111-11138SI).

Author Contributions

Study design: WTC, PSH, LWS, CTL, HST, ZCC, PCH, and CSH; Data collection: WTC, PSH, PCH, and CSH; Data analysis: WTC, CTL, HST, YCL, JYS, and CSH; Writing: WTC, PSH, LWS, CTL, HST, ZCC, PCH, and CSH; Final approval: WTC, PSH, LWS, CTL, HST, ZCC, PCH, and CSH; Agreement to be accountable for this work: WTC, PSH, LWS, CTL, HST, ZCC, PCH, and CSH

Data Availability Statement

The original data is available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author

References

- 1) Davies MG: Criticial limb ischemia: epidemiology. Methodist Debakey Cardiovasc J, 2012; 8: 10-14

- 2) Novo S, Coppola G and Milio G: Critical limb ischemia: definition and natural history. Curr Drug Targets Cardiovasc Haematol Disord, 2004; 4: 219-225

- 3) Kinlay S: Management of Critical Limb Ischemia. Circ Cardiovasc Interv, 2016; 9: e001946

- 4) Koyama Y, Migita S, Shimodai-Yamada S, Suzuki M, Uto K, Okumura Y, Ohura N and Hao H: Pathology of Critical Limb Ischemia; Comparison of Plaque Characteristics Between Anterior and Posterior Tibial Arteries. J Atheroscler Thromb, 2023; 30: 1893-1904

- 5) Nishijima A, Yamamoto N, Yoshida R, Hozawa K, Yanagibayashi S, Takikawa M, Hayasaka R, Nishijima J, Gosho M and Nishijima H: Coronary Artery Disease in Patients with Critical Limb Ischemia Undergoing Major Amputation or Not. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open, 2017; 5: e1377

- 6) Thukkani AK and Kinlay S: Endovascular intervention for peripheral artery disease. Circ Res, 2015; 116: 1599-1613

- 7) Hernandez-Suarez DF, Nunez-Medina H, Scott SA, Lopez-Candales A, Wiley JM, Garcia MJ, Melin K, Nieves-Borrero K, Rodriguez-Ruiz C, Marshall L and Duconge J: Effect of cilostazol on platelet reactivity among patients with peripheral artery disease on clopidogrel therapy. Drug Metab Pers Ther, 2018; 33: 49-55

- 8) Kuo FY, Lee CH, Lan WR, Su CH, Lee WL, Wang YC, Lin WS, Chu PH, Lu TM, Lo PH, Tsukiyama S, Yang WC, Cheng LC, Huang CL, Yin WH and Liu PY: Effect of CYP2C19 status on platelet reactivity in Taiwanese acute coronary syndrome patients switching to prasugrel from clopidogrel: Switch Study. J Formos Med Assoc, 2022;

- 9) Leeper NJ, Kullo IJ and Cooke JP: Genetics of peripheral artery disease. Circulation, 2012; 125: 3220-3228

- 10) Tangelder MJ, Nwachuku CE, Jaff M, Baumgartner I, Duggal A, Adams G, Ansel G, Grosso M, Mercuri M, Shi M, Minar E and Moll FL: A review of antithrombotic therapy and the rationale and design of the randomized edoxaban in patients with peripheral artery disease (ePAD) trial adding edoxaban or clopidogrel to aspirin after femoropopliteal endovascular intervention. J Endovasc Ther, 2015; 22: 261-268

- 11) Yoshioka N, Tokuda T, Koyama A, Yamada T, Shimamura K, Nishikawa R, Morita Y, Morishima I and investigators AP: Association between High Bleeding Risk and 2-Year Mortality in Patients with Chronic Limb-Threatening Ischemia. J Atheroscler Thromb, 2023; 30: 1674-1686

- 12) Tokuda T, Yoshioka N, Koyama A, Yamada T, Shimamura K and Nishikawa R: Chronic Limb-Threatening Ischemia is a Residual Bleeding Risk Factor among Patients with Lower Extremity Artery Disease. J Atheroscler Thromb, 2024; 31: 100-108

- 13) Sun Y, Lu Q, Tao X, Cheng B and Yang G: Cyp2C19*2 Polymorphism Related to Clopidogrel Resistance in Patients With Coronary Heart Disease, Especially in the Asian Population: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Genet, 2020; 11: 576046

- 14) Dehbozorgi M, Kamalidehghan B, Hosseini I, Dehghanfard Z, Sangtarash MH, Firoozi M, Ahmadipour F, Meng GY and Houshmand M: Prevalence of the CYP2C19*2 (681 G>A), *3 (636 G>A) and *17 (806 C>T) alleles among an Iranian population of different ethnicities. Mol Med Rep, 2018; 17: 4195-4202

- 15) Lee J, Cheng N, Tai H, Jimmy Juang J, Wu C, Lin L, Hwang J, Lin J, Chiang F and Tsai C: CYP2C19 Polymorphism is Associated With Amputation Rates in Patients Taking Clopidogrel After Endovascular Intervention for Critical Limb Ischaemia. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg, 2019; 58: 373-382

- 16) Claassens DMF, Vos GJA, Bergmeijer TO, Hermanides RS, van ‘t Hof AWJ, van der Harst P, Barbato E, Morisco C, Tjon Joe Gin RM, Asselbergs FW, Mosterd A, Herrman JR, Dewilde WJM, Janssen PWA, Kelder JC, Postma MJ, de Boer A, Boersma C, Deneer VHM and Ten Berg JM: A Genotype-Guided Strategy for Oral P2Y12 Inhibitors in Primary PCI. N Engl J Med, 2019; 381: 1621-1631

- 17) Pereira NL, Farkouh ME, So D, Lennon R, Geller N, Mathew V, Bell M, Bae JH, Jeong MH, Chavez I, Gordon P, Abbott JD, Cagin C, Baudhuin L, Fu YP, Goodman SG, Hasan A, Iturriaga E, Lerman A, Sidhu M, Tanguay JF, Wang L, Weinshilboum R, Welsh R, Rosenberg Y, Bailey K and Rihal C: Effect of Genotype-Guided Oral P2Y12 Inhibitor Selection vs Conventional Clopidogrel Therapy on Ischemic Outcomes After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: The TAILOR-PCI Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA, 2020; 324: 761-771

- 18) Angiolillo DJ, Capodanno D, Danchin N, Simon T, Bergmeijer TO, Ten Berg JM, Sibbing D and Price MJ: Derivation, Validation, and Prognostic Utility of a Prediction Rule for Nonresponse to Clopidogrel: The ABCD-GENE Score. JACC Cardiovasc Interv, 2020; 13: 606-617

- 19) Breet NJ, van Werkum JW, Bouman HJ, Kelder JC, Ruven HJ, Bal ET, Deneer VH, Harmsze AM, van der Heyden JA, Rensing BJ, Suttorp MJ, Hackeng CM and ten Berg JM: Comparison of platelet function tests in predicting clinical outcome in patients undergoing coronary stent implantation. JAMA, 2010; 303: 754-762

- 20) Simon T, Verstuyft C, Mary-Krause M, Quteineh L, Drouet E, Meneveau N, Steg PG, Ferrieres J, Danchin N, Becquemont L, French Registry of Acute STE and Non STEMII: Genetic determinants of response to clopidogrel and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med, 2009; 360: 363-375

- 21) Saito Y, Nishi T, Wakabayashi S, Ohno Y, Kitahara H, Ariyoshi N and Kobayashi Y: Validation of the ABCD-GENE score to identify high platelet reactivity in east Asian patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Int J Cardiol, 2021; 327: 15-18

- 22) Chapter 1: Definition and classification of CKD. Kidney Int Suppl (2011), 2013; 3: 19-62

- 23) d’Emden MC, Shaw JE, Jones GR and Cheung NW: Guidance concerning the use of glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) for the diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. Med J Aust, 2015; 203: 89-90

- 24) Kerr KF, Wang Z, Janes H, McClelland RL, Psaty BM and Pepe MS: Net reclassification indices for evaluating risk prediction instruments: a critical review. Epidemiology, 2014; 25: 114-121

- 25) Capodanno D, Angiolillo DJ, Lennon RJ, Goodman SG, Kim SW, O’Cochlain F, So DY, Sweeney J, Rihal CS, Farkouh M and Pereira NL: ABCD-GENE Score and Clinical Outcomes Following Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: Insights from the TAILOR-PCI Trial. J Am Heart Assoc, 2022; 11: e024156

- 26) Thomas CD, Franchi F, Keeley EC, Rossi JS, Winget M, David Anderson R, Dempsey AL, Gong Y, Gower MN, Kerensky RA, Kulick N, Malave JG, McDonough CW, Mulrenin IR, Starostik P, Beitelshees AL, Johnson JA, Stouffer GA, Winterstein AG, Angiolillo DJ, Lee CR and Cavallari LH: Impact of the ABCD-GENE Score on Clopidogrel Clinical Effectiveness after PCI: A Multi-Site, Real-World Investigation. Clin Pharmacol Ther, 2022; 112: 146-155

- 27) Dai L, Xu J, Yan H, Chen Z, Pan Y, Meng X, Li H and Wang Y: Application of Age, Body Mass Index, Chronic Kidney Disease, Diabetes, and Genotyping Score for Efficacy of Clopidogrel: Secondary Analysis of the CHANCE Trial. Stroke, 2022; 53: 465-472

- 28) Wu H, Li X, Qian J, Zhao X, Yao Y, Lv Q and Ge J: Development and Validation of a Novel Tool for the Prediction of Clopidogrel Response in Chinese Acute Coronary Syndrome Patients: The GeneFA Score. Front Pharmacol, 2022; 13: 854867

- 29) Qu Y, Yang J, Zhang F, Li C, Dai Y, Yang H, Gao Y, Pan Y, Yao K, Huang D, Lu H, Ma J, Qian J and Ge J: Relationship between body mass index and outcomes of coronary artery disease in Asian population: Insight from the FOCUS registry. Int J Cardiol, 2020; 300: 262-267

- 30) Choi H, Nam HS and Han E: Body mass index and clinical outcomes in patients after ischaemic stroke in South Korea: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open, 2019; 9: e028880

- 31) Chen Y, Copeland WK, Vedanthan R, Grant E, Lee JE, Gu D, Gupta PC, Ramadas K, Inoue M, Tsugane S, Tamakoshi A, Gao YT, Yuan JM, Shu XO, Ozasa K, Tsuji I, Kakizaki M, Tanaka H, Nishino Y, Chen CJ, Wang R, Yoo KY, Ahn YO, Ahsan H, Pan WH, Chen CS, Pednekar MS, Sauvaget C, Sasazuki S, Yang G, Koh WP, Xiang YB, Ohishi W, Watanabe T, Sugawara Y, Matsuo K, You SL, Park SK, Kim DH, Parvez F, Chuang SY, Ge W, Rolland B, McLerran D, Sinha R, Thornquist M, Kang D, Feng Z, Boffetta P, Zheng W, He J and Potter JD: Association between body mass index and cardiovascular disease mortality in east Asians and south Asians: pooled analysis of prospective data from the Asia Cohort Consortium. BMJ, 2013; 347: f5446

- 32) Knowles JW, Assimes TL, Li J, Quertermous T and Cooke JP: Genetic susceptibility to peripheral arterial disease: a dark corner in vascular biology. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 2007; 27: 2068-2078

- 33) Guo B, Tan Q, Guo D, Shi Z, Zhang C and Guo W: Patients carrying CYP2C19 loss of function alleles have a reduced response to clopidogrel therapy and a greater risk of in-stent restenosis after endovascular treatment of lower extremity peripheral arterial disease. J Vasc Surg, 2014; 60: 993-1001

- 34) Osnabrugge RL, Head SJ, Zijlstra F, ten Berg JM, Hunink MG, Kappetein AP and Janssens AC: A systematic review and critical assessment of 11 discordant meta-analyses on reduced-function CYP2C19 genotype and risk of adverse clinical outcomes in clopidogrel users. Genet Med, 2015; 17: 3-11

- 35) Gutierrez JA, Heizer GM, Jones WS, Rockhold FW, Mahaffey KW, Fowkes FGR, Berger JS, Baumgartner I, Held P, Katona BG, Norgren L, Blomster JI, Hiatt WR and Patel MR: CYP2C19 status and risk of major adverse cardiovascular events in peripheral artery disease: Insights from the EUCLID Trial. Am Heart J, 2020; 229: 118-120

- 36) Janssen PW and ten Berg JM: Platelet function testing and tailored antiplatelet therapy. J Cardiovasc Transl Res, 2013; 6: 316-328

- 37) Su-Yin DT: Using Pharmacogenetic Testing or Platelet Reactivity Testing to Tailor Antiplatelet Therapy: Are Asians different from Caucasians? Eur Cardiol, 2018; 13: 112-114