2021 Volume 27 Pages 11-25

2021 Volume 27 Pages 11-25

The "preserved tree system" and "preserved forest system" aim to preserve trees and forests in cities in Japan, and are operated by local governments. We conducted a questionnaire of the operators of the preserved tree system to examine their awareness of the systems in Nagoya (215 operators) and Shizuoka (60 operators), and clarified the relationships among operators, local governments, and community residents not involved in tree management. Questionnaires were returned by 117 (Nagoya) and 30 (Shizuoka) operators. The results were as follows: 1) Although local governments and operators agreed on the goals of the system (green preservation, improving aesthetic appeal, and preservation of trees with historical and cultural value), there were concerns over the associated costs and economic burden faced by the management; 2) There was a risk of conflict between the operators and community residents because calls for preservation by neighboring residents increased when operators stopped tree management. For sustainable preservation of designated trees in the local environment, promotion of cooperation between community residents and operators is crucial.

The "preserved tree system" and "preserved forest system" were initiated to preserve giant trees and forests in urban areas of Japan 1. These systems aim to conserve trees and forests and improve favorable urban environments, with respect to the "Act on Preservation of Trees for Maintenance of Scenic Beauty of Cities" (Ministry of Justice, 2009a), and the related ordinances of each local government. At the end of 2017, approximately 65,000 preserved trees and approximately 8,200 preserved forests were covered by this system, under 378 local governments nationwide (Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport, and Tourism: MLIT, 2017). The actual management is entrusted to the residents, while the local government assists with management costs and supplies.

A previous study on these systems by Ishizaki (1994), which investigated the species and geographical distribution of preserved trees in Tokyo, showed that they were affected by land ownership. Setsu et al. (1995) pointed out that excessive pruning of preserved trees to address concerns about fallen branches, conflicted with the idea of preserving trees chosen for their "aesthetic appeal" (Setsu et al., 1995). A survey of former owners of preserved trees (people who had previously owned preserved trees) by Sawaki and Kuwae (2002) showed that complaints from neighboring residents relating to the preserved trees became too onerous a responsibility; the survey also indicated that maintenance management activities and recreational use should be carried out collaboratively, based on a mutual understanding between the owner and neighboring residents.

Previous studies have focused on the constituent tree species of preserved tree systems and the attitude of their owners; however, little research has investigated the relationships between neighboring residents and local governments. A policy report on urban greening and green space conservation, published by the MLIT, stated "creating a place for collaboration with the participation of local residents and NPOs at each stage of conservation, creation, and management of greenery and open spaces" (MLIT, 2019). Previous studies on the relationship between the operators and neighboring residents are also lacking; basic research is also needed on the relationship between residents and owners, to promote "mutual understanding between owners and neighboring residents" (Sawaki and Kuwae, 2002). Setsu et al. (1995) showed that privately-owned trees are tended to be managed by individuals, while trees at shrines and temples are tended to be managed by service supporters such as parishioners and presidents. A focus on the preserved trees at shrines and temples, therefore, will provide more insight into the behavior and involvement of local governments, the tree preservation managers, and neighboring residents.

The present study aimed to increase awareness of tree management and preservation systems, as well as investigate the relationships among operators 2, neighboring residents, and local governments. In addition, the study aimed to clarify issues within the system, based on a survey amongst the operators of preserved trees.

The survey methods incorporated a literature review, interviews with the operators of preserved tree system, and questionnaire surveys. The literature review examined newspaper articles on preserved trees, as well as reports on the geological history and tree preservation systems of the survey sites. The newspaper article review focused on the "Asahi Shimbun," "Chunichi Shimbun/Tokyo Shimbun," "Nihon Keizai Shimbun," "Mainichi Shimbun," and "Yomiuri Shimbun" databases. A keyword search, using the term "preserved tree," resulted in 255, 187, 10, 165, and 175 articles for each respective database mentioned above.

We also searched internet-based homepages or greening policies of local governments for information on preserved tree species, owners, and aid provided for tree preservation, such as subsidies for management costs, installation of signboards, and tree vigor diagnoses (Hachinohe City, 2020). In the present study, we also quantitatively analyzed the annual payment per preserved tree. Each prefecture in each area is shown as below. Hokkaido: Hokkaido, Tohoku: Aomori, Iwate, Miyagi, Akita, Yamagata, Fukushima, Kanto: Ibaraki, Tochigi, Gunma, Saitama, Chiba, Tokyo, Kanagawa, Yamanashi, Chubu: Niigata, Toyama, Ishikawa, Nagano, Gifu, Shizuoka, Aichi, Kansai: Mie, Shiga, Kyoto, Osaka, Hyogo, Nara, Wakayama, Chugoku/ Shikoku: Tottori, Okayama, Hiroshima, Yamaguchi, Kochi, Tokushima, Kagawa, Ehime, Kyushu: Fukuoka, Saga, Nagasaki, Kumamoto, Oita, Miyazaki, Kagoshima, Okinawa. There are no local governments operating this system in Fukui and Shimane.

Furthermore, we conducted a morphological analysis on the text describing this system on the homepage of each local government website, using the "KH Coder" text analysis software. Morphological analysis is finding morphemes (minimum sound patterns with meaning) from sentences and dividing them into units (Otsuki et al., 2018). Thus, we extracted words that were frequently used by local governments when explaining the system to residents and examined the awareness of the residents regarding the system used by their local governments. Data acquisition and analysis were conducted on November 12th and 13th, 2019, while the morphological analysis engine used was "MeCab."

The interview and questionnaire surveys were conducted in Nagoya (Aichi Prefecture) and Shizuoka (Shizuoka Prefecture). In Nagoya, trees in the preservation system have been registered since 1973 (City of Nagoya, 2020), while in Shizuoka, the system was introduced in 2015 (City of Shizuoka, 2016); these two sites were chosen for determining the correlation between years since the system started, and awareness of the system. Table 1 shows the current (as at 2020) state of implementation of the system.

| Nagoya | Shizuoka | |

| System started in | 1973 | 2015 |

| Number of Trees and Forests | Preserved Trees: 856 Preserved Forests: 2 |

Preserved Trees: 42 Preserved Forests: 39 |

| Fixed subsidy amount per one Preserved Tree | 3,000 yen | - |

| Subsidies to tree management | 1/2 of the cost by application (up to 300,000 yen) | |

| Other subsidies | Tree diagnosis Signboard installation |

Supplying materials (e.g., garbage bags) Signboard installation |

| Disclosure of information about Preserved Tree | Species | Species and Location |

Source: Based on the description on each local government website in Nagoya and Shizuoka (City of Nagoya, 2020; City of Shizuoka, 2020).

Note: Subsidies in Nagoya include those from Nagoya City Green Association.

In interview surveys, the views of operators on the historical and cultural value of trees were acquired. Interviews were conducted on 36 days between July 2017 and January 2019. In questionnaire surveys, we asked questions on difficulties relating to tree management; the existence and details of historical and cultural values; and the motives for introducing the system. In the design of the questionnaire, several questions were added or changed, based on questionnaire survey that was previously conducted in Nagoya on the owners of preserved trees, in 2009 (City of Nagoya, 2009). Although there are some differences from the present survey (the implementing respondents and the method of sending the questionnaire), it is provided here to clarify how their awareness has changed since 2009. The subjects of the present survey were the operators of preserved tree system and forests of shrines and temples in both cities (Nagoya: 215 operators, Shizuoka: 60 operators) 3. The survey was conducted from November 2018 to February 2019; the questionnaire was distributed by visiting each shrine and temple physically, while the response was requested by mail.

In addition to the simple tabulation of the questionnaire, a cross-analysis was performed on questions with a large number of responses ("Yes," "No," "I think it is necessary," or "Neither can be said"), to clarify the presence or absence, and strength of the correlation amongst the responses. The Phi coefficient was used to determine the positive and negative correlations, and Cramer's V was used to determine the strength. According to previous research, a relatively strong correlation is indicated if Cramer's V is 0.2 or more (Hojo, 2010).

The "Act on Preservation of Trees for Maintenance of Scenic Beauty of Cities" was initiated in 1962 to secure green spaces in cities (Tahara et al., 2011). The minutes of the Diet on this law confirmed references to the owners; however, there were no references made to the neighbors not involved in tree management. Before the enactment of the bill, there was specific concern regarding infringements on the rights of the owner, which stated that, "it is an infringement of private rights to any extent 4." Twenty years after the enactment of the bill, there is still ongoing debate as to what kind of assistance is needed to prevent the de-designation of preserved trees 5.

Furthermore, there were records referring to the trees to be designated for preservation: "famous trees or old trees, which are not designated by the Act on Protection of Cultural Properties, can be specified by decisions by the mayor of each local government 6," thus showing an intention to allow local government to exercise discretion on such trees. In addition, the "Act on Protection of Cultural Properties," which preserves and utilizes "cultural properties with a high historical or artistic value in Japan," (Ministry of Justice, 2009b) was stated; "famous trees or old trees" that have historical and cultural value were not excluded in the designation of this system.

Several local governments (Kasugai City, Aichi Prefecture) included hedges in the target. The testimony of local government officials was also obtained: "The preserved tree system is less restrictive than other systems, such as the green conservation areas 7" As nearly 90% of designated cases (trees: 61,855, forests: 8,002) were based on the ordinances of each local government (MLIT, 2017), local governments were given a certain amount of discretion.

Several local governments specify conditions, such as "trees that have been popular as symbolic trees in the town" (Sendai City, Miyagi Prefecture), as requirements for designation. While the preserved tree system mainly targets greening and green preservation, the designation of trees with historical and cultural value is also made at the discretion of local governments.

In summary, the issues faced by operators changed, from concerns regarding infringements on private rights, to the need for assistance to maintain preserved trees. However, the relationship with neighboring residents was not considered by the Diet. In addition, discussions even before the enactment of the bill showed the intention to hand the discretion for the designation of trees with historical and cultural value to the local governments. This remains the same till date.

Current Characteristics of Preserved Tree SystemsWe obtained the information regarding preserved trees from a number of local governments. The information obtained was as follows: species: 124 (32.8%); owners: 61 (16.1%); fixed-amount subsidies: 104 (27.5%); description of the system: 204 (54.0%).

Regarding the species of preserved trees, Nakajima (1986) pointed out the existence of the northern Japanese type, where Zelkova serrata is abundant, and the southwestern Japanese type, which is dominated by Cinnamomum camphora. The current trends seen in the top five species are displayed in Figs. 1 and 9. "Pine trees" are all trees with "Matsu (pine)" at the end. "Castanopsis" are Castanopsis sieboldii and Castanopsis cuspidata (Iokawa, 2016). The abundance of Cinnamomum camphora increased in a southern region, while that of pine trees decreased. Zelkova serrata was abundant in the Kanto region, but Ginkgo biloba did not show any significant changes in abundance. This is largely in line with trends in the 1980s (Nakajima, 1986).

Percentage of top five tree species by region.

Note: "n" stands for the number of preserved trees.

Source: Based on the description on each local government's website (City of Nagoya, 2020) etc.

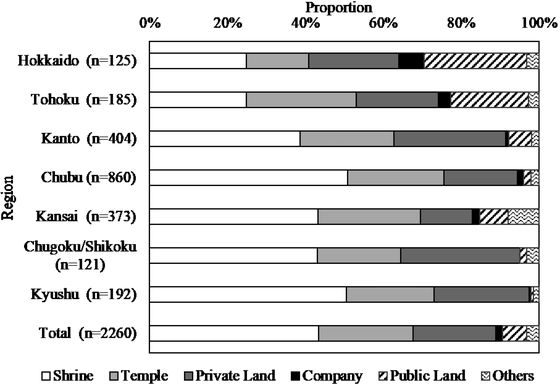

The nationwide types of owners were roughly classified by Nakajima (1986) into private owners, religious facilities (temples, shrines, and churches), companies, and public land, and their ratios across different regions were calculated. Figure 2 shows the proportion of preserved tree owners in the above categories, across different regions: the proportion of public ownership was high in the Hokkaido and Tohoku regions. In addition, shrines and temples accounted for the ownership of more than 60% of the total population of preserved trees nationwide 8 In agreement with the observation made by Nakajima that half of the preserved trees exist in religious institutions, it was shown that the present day preserved tree system is especially prominent at shrines and temples.

Percentage of owners by region.

Note: "n" stands for the number of owners of preserved trees.

Source: Based on the description on each local government's website (City of Shizuoka, 2020) etc.

Concerning fixed-quantity subsidies, the average amount was 4454 (± 3130) yen, the maximum was 20000 yen, and the minimum was 1000 yen. We focused on fixed-quantity subsidies because they are easy to analyze quantitatively. However, in the cases of Nagoya and Shizuoka (Table 1), which were our target areas for interviews and questionnaire surveys, further subsidies are allocated in addition to the fixed-quantity subsidy, such as subsidies for tree vigor diagnosis or the supply of materials. It is expected that the amount of subsidy differs in each local government.

Figure 3 shows the top 15 words most frequently used to describe the system in each local government. The more frequent use of the words "green" and "environment" than the word "scenery," means that the local government focuses on greening and green conservation, ahead of maintenance of scenery. Conversely, according to MLIT, "Old trees and famous trees that have been popular in the area" are specified by the ordinance, while those with historical and cultural value are also subject to conservation.

Words that frequently appear in public relations about system of each local government.

Furthermore, "while greenery is being lost due to urbanization, by designating famous trees and old trees in the city as preserved trees, the scenic beauty of the city is maintained by the citizens with cooperation of everyone" (City of Nagoya, 2020). In addition, "Trees or forests that need to be preserved are designated as 'preserved trees (or forests)' to preserve the greenery of giant trees and old trees" in accordance with the basic principles of the Shizuoka City Green Ordinance (City of Shizuoka, 2020). The purpose of this system is to preserve green areas, aesthetics, and historical and cultural values, as well as MLIT's state.

To summarize: (1) Approximately two-thirds of the owners of preserved trees are shrines and temples; (2) The amount of subsidies for preserved trees differs, depending on local governments; and (3) The aim of local governments is greening and green preservation, followed by scenery.

Relationships between Preserved Tree Operators and Neighboring ResidentsIn this section, we examine the relationships among preserved tree operators, and neighboring residents. From a survey of individual newspaper articles, there were three types of newspaper articles: (1) Those related to the movements of neighboring residents (e.g., Tokyo Shimbun, 2019); (2) Those related to systems, especially the movements of local governments (e.g., Yomiuri Shimbun, 2016); and (3) Those related to the introduction of preserved trees themselves and to the descriptions of damage to preserved trees caused by typhoons (e.g., Chunichi Shimbun, 2009). Figure 4 shows the transition of these descriptions over the decades. Many descriptions of systems, relating to the type (2) newspaper articles, were found in the 1990s, with most of them focusing on local governments that were newly designating trees or forests for preservation. The type (3) articles on preserved trees accounted for nearly half of those from the 2010s, which is thought to be due to the increase in reports of damage caused by natural disasters.

Historical transition of newspaper article content.

Source: Based on the article contents on each newspaper article archive (Asahi Shimbun, 2019; Chunichi Shimbun, 2019; Mainichi Shimbun, 2019; Nihon Keizai Shimbun, 2019; Yomiuri Shimbun, 2019).

The type (1) articles on the movements of neighboring residents accounted for approximately 10% of articles since the 1990s; there were also articles relating to regional geography published by residents (e.g., Chunichi Shimbun, 1992) as well as articles on the systems used as a means of forest preservation (e.g., Asahi Shimbun, 2014).

We focused on articles in which residents were opposed to the logging of preserved trees. In these cases, neighboring residents mounted anti-logging protests, after operators voluntarily or unavoidably undertook de-designation; for example, Yomiuri Shimbun (2006) reported that after operators decided to cancel the designation of preserved trees, residents protested logging. Residents who carried out these protests claimed that preserved trees should be conserved as precious trees (Asahi Shimbun, 2005). Moreover, "shrines and temples are given preferential treatment as religious corporations" (Asahi Shimbun, 1991). Shrines and temples are religious institutions, and the articles suggested that there was some resistance to the inclusion of religious organizations in the scope of public systems.

The abovementioned situations demonstrated that neighboring residents may oppose the logging of preserved trees, as well as increase their calls for tree preservation, in cases of logging of preserved trees. Therefore, we discuss the current situation of preserved tree operators, based on the questionnaire and interview surveys in the present study.

The number of valid responses from Nagoya was 117 (54.4%) and that from Shizuoka, 30 (50.0%).

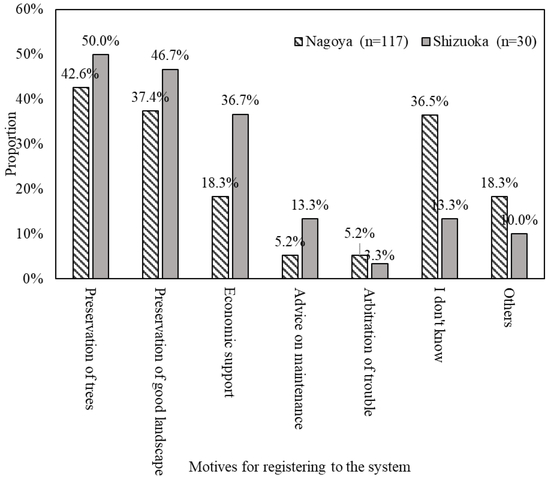

The motives for registering for the preserved tree system are summarized in Fig. 5. More than 30% of the respondents in Nagoya answered, "I don't know/there is no particular reason." Of the 24 responses to open-ended questions, 15 respondents said that they had taken over from their predecessor and that the trees had already been registered. It can be assumed that, in Nagoya, attitude and awareness regarding the system have become entrenched and routine in the 40 years that have passed since the system was implemented. Conversely, in both cities, most respondents answered that, "I thought that old trees and famous trees in the area should be preserved" (preservation of famous trees), followed by, "I thought that it was necessary for the landscape of shrines and temples" (preservation of good landscape). Among the 107 responses to open-ended questions regarding the system, 28 were of the opinion that, "The shrine is a 'Mori' (forest) and trees are necessary," thus confirming that people wanted to preserve symbolic trees or forests. In addition, 27 stated that, "It is a precious big tree, and it is disheartening to lose it," thus emphasizing a greening aspect. The operators were inclined to value support from a cultural or spiritual perspective more than receiving assistance on practical matters such as "economic support" and "advice on maintenance."

Motives for registering to the system.

Note: multiple answers allowed except for "I don't know."

Regarding the correlation between historical and cultural values, compared with other aspects (Table 2, shaded items), a weak positive correlation was found between a positive awareness of the system and the existence of application motives. There was a positive correlation between the existence of management difficulties and the presence of historical and cultural values.

| Question A | Question B | Correlation | |

| Sign | Strength | ||

| Difficulties of tree maintenance | Presence of complaints | + | 0.3354 |

| Awareness of the system | Presence of motives toward the system | + | 0.2560 |

| Difficulties of tree maintenance | Presence of motives toward the system | + | 0.2310 |

| Difficulties of tree maintenance | Historical/ Cultural value | + | 0.1646 |

| Awareness of disclosing information | Presence of complaints | − | 0.1606 |

| Historical/ Cultural value | Presence of motives toward the system | + | 0.1530 |

| Awareness of the system | Presence of complaints | − | 0.1463 |

| Awareness of the system | Historical/ Cultural value | + | 0.1438 |

| Presence of complaints | Historical/ Cultural value | + | 0.1340 |

| Awareness of disclosing information | Presence of motives toward the system | + | 0.1051 |

Note: Shaded items are related to historical and cultural values.

Regarding motives for registration, assuming that historical and cultural values pre-existed, the system was introduced to preserve trees. In Nagoya, almost half of the historical values and cultural values relating to trees were unknown when they were first introduced; however, 13 of the 14 cases were regarded as historical and cultural trees before 1970, when institutional efforts began. It is, therefore, highly possible that historical and cultural values were effective in motivating the operators for the preservation of specific trees. Conversely, from the positive correlation between the existence of management difficulties and the presence of historical and cultural values, it appears that such difficulties will not disappear, even if the governing body understands the historical and cultural value of the preserved tree.

Relating to motives for registration, a chief priest of a shrine who was registered in the system in the past, but who deregistered due to dissatisfaction at the "deterioration of the tree," stated that, "Because it is a big tree, it is necessary to support it." Furthermore, a typhoon broke the trunk of the preserved tree, and a parishioner of the shrine, who canceled the application for registration, said "It is quite difficult to manage the preserved tree nowadays." Even at the local government level there is a concern about such a situation, with one of the people in charge saying, "We try to discuss with the operator as much as possible about the parts damaged by typhoons; it might be difficult, however."

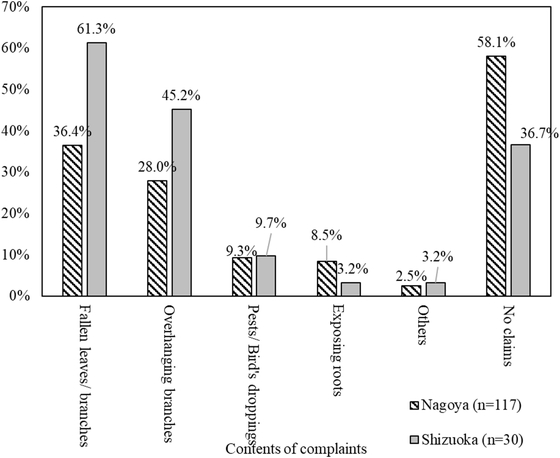

Relationship between Operators and Neighboring ResidentsFigure 6 shows the complaints from neighboring residents and the reasons for these complaints. Of the respondents, 40% in Nagoya and 60% in Shizuoka answered that they had received complaints. Many of the complaints related to leaf fall and branch overhang. Of the 38 responses to open-ended questions, 21 respondents received complaints related to leaf litter, such as "deciduous leaves clogging the gutter of the neighboring house" or "herbicides were sprayed without our permission." Several respondents said, "As a local deity, a preserved tree is necessary, but I am worried about the impact on the surrounding area because of the large tree." Another answer was, "If there is no actual harm to you, 'save it,' if there is harm, 'cut it, or take care of it,'" thus showing the difficulty faced by the neighboring residents while maintaining the preserved tree.

Complaints from neighboring residents.

Note: multiple answers allowed except for "No claims."

Table 2 shows that there was a strong correlation between the difficulties in tree management and complaints from neighboring residents; the assumption cannot be made that receiving a complaint worsens the awareness of tree management, or that an aspect that makes it difficult to manage the tree (such as litter), is causing the complaint. It will nevertheless be necessary to introduce measures to resolve tree management difficulties and thus prevent complaints.

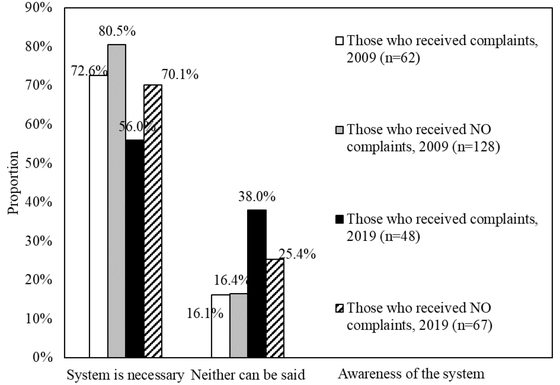

We also examined the differences between the questionnaire survey conducted in Nagoya in 2009 and the present survey; Figure 7 shows the relationship between the complaints and awareness of the system in 2009, compared with that in the present study in 2019. Even after receiving complaints, more than half of the respondents answered that the "System is necessary." However, the percentage of respondents who reported that they received complaints increased (in 2009: 32.6% while in 2019: 41.7%). In addition, respondents in this survey who received complaints were more likely to answer, "Neither can be said," than those in 2009.

Relationship between presence of complaints and the awareness of the system.

Note: Data in 2009 was collected by City of Nagoya (2009).

Relationships with neighboring residents were not the only difficulty faced by the managers. Figure 8 shows the age structure of preserved tree operators; most managers in both cities were in their 60s or older. Even in the open-ended responses, there were opinions that, "I think that maintenance will become difficult in the future due to the declining birthrate and aging population." In addition, there were opinions that there was a shortage of management personnel, and that the continuity of independent management was being jeopardized by the aging population. To solve this problem regarding shortage of operators, a shrine in Nagoya confirmed that it was recruiting volunteers. Considering that nearly 70% of the shrines in Nagoya answered that they were managed by the parishioners, such recruitment efforts seem to be a new movement that is not bound by the historical management by parishioners.

Age structure of preservation tree operators.

Note: "n" stands for the number of operators.

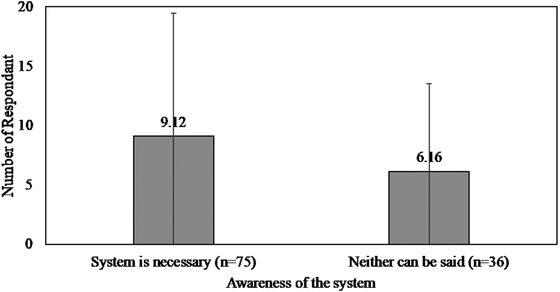

The correlation between the number of operators and the responses revealed differences in the awareness of the system. Figure 9 shows the average number of operators in each response group for each response, related to their awareness of the system. Both the average number and maximum number of operators in the group, who stated that the "System is necessary," exceeded that of the group that answered, "Neither can be said." In contrast, there were no significant differences in the answers to the other questions about difficulties in management and the presence of complaints from neighboring residents. From the above results, it can be assumed that an increase in the number of operators improves the overall awareness of the system.

Average number of operators and their awareness of the system in Nagoya.

It seems difficult, however, to persuade owners to accept operators who are volunteers at all shrines and temples, as reflected by the reaction to the awareness of disclosing information on preserved trees (tree species composition and location) to third parties. In both cities, the responses were divided into two categories: "It is okay to open to the public," and "Neither can be said" (Fig. 10). In the open-ended responses, those who answered, "It is okay to open to the public" justified their answer as meaning, "It can be made known by making it public," and, "It is a public business, so there is no resistance to disclosing information." Respondents who answered, "Neither can be said," and, "We do not want to disclose," were concerned about the disadvantages of increasing the number of visitors or damage. There was also an opinion that, "the preserved trees of the shrine should be managed by the parishioners," and it is conceivable that there is a similar dichotomy regarding the widespread recruitment of operators.

Awareness of disclosing information on preserved trees.

In the "Act on Preservation of Trees for Maintenance of Scenic Beauty of Cities," preserved trees are designated for protection to "improve the sound environment of the city" and to "maintain aesthetic areas." (MLIT, 2017). As mentioned in results of questionnaire survey in Nagoya and Shizuoka, the aims of local governments are greening/green preservation, improving aesthetic appeal, and the preservation of trees of historical and cultural value. Considering that there were many survey answers such as, "I thought that old trees and famous trees in the area should be left," and, "I thought that it was necessary for the scenery of shrines and temples," there was clear consensus that local government should maintain a good landscape and preserve the historical and cultural values of trees. Conversely, several operators were dissatisfied with the designation of trees, when there was a deterioration in the number of trees.

The relationship between neighboring residents and operators, showed clear signs of potential conflict between them. Neighboring residents complained regularly to the operator but when the operator retired from management, residents expressed a stronger need for preservation of trees; the attitudes of the neighboring residents are therefore changeable.

The number of operators that received complaints has increased, with a strong correlation between the complaints and the difficulty in managing trees (Table 1). In addition, judicial decisions that prioritize the rights of adjacent landowners over the trees at shrines (Mainichi Shimbun, 2016; Morimoto, 2019) place even more pressure on operators of the preserved tree system.

Recommendations for Possible Inclusion of Neighboring Residents or OutsidersSawaki and Kuwae (2002) have reported that the expectations of former owners of preserved trees (people who used to own preserved trees) could be classified into two types: expectations for awareness, such as the level of understanding in neighboring resident groups, and expectations for financial support from the government.

Given that the greatest expectations of the operators were cultural and spiritual, and that public support was limited, this section describes the possibility of including neighbors and outsiders in tree preservation.

Our survey showed that the larger the number of operators, the more positive the awareness of the system (Fig. 9). To prevent conflicts between operators and neighboring residents, it is necessary to bridge the gap between them for better operation of the system.

Regarding the relationship between the community and religious institutions, Susaki (2017) pointed out that those who practice other religions may face barriers to involvement with shrines or temples. A system that considers the diversity of religion should therefore be created. Studies have also pointed out that the acceptance of visitors from the outside can reconfirm the significance of the folklore of an area (Kamei, 2015). Conversely, if historical and cultural values are already shared within the community, the entry of outsiders may lead to conflict (Yagihashi, 2015). In the discourse on multicultural coexistence, the coexistence of the majority group and minorities (newcomers) is desirable for the system (Kurimoto, 2016). Opinions on information disclosure, however, were divided (Fig. 10); certain responses indicated that the preserved trees of shrines should be managed by the parishioners, showing a reluctance at certain shrines and temples to accept outsiders; whereas, certain responses showed that disclosing the information to public would be beneficial. A system for accepting outsiders has not yet been established; therefore, it should be clarified at the time of registering for the system, whether the operator wishes to include outsiders or not. If operators can manage the trees without any difficulties, the trees are likely to be preserved. If, however, there are problems with the operation, it may be necessary to classify cases according to the actual conditions of the region, which may, for example, require additional support from external volunteers.

Impacts of Historical and Cultural Values on Preserved TreesBased on the present study, we can conclude that the historical and cultural values of Nagoya were drivers in preserving certain trees; however, the question remains whether historical and cultural values will continue to be effective in preserving trees. Previous research has pointed out that folklore may not be passed down if there are changes in autonomous regions (Aiba and Harada, 2019). In Nagoya, one-third of the respondents answered, "I don't know/There is no particular reason," for the motive behind the application for registration (Fig. 5). Even if the historical and cultural values of trees were understood by operators, there could still be difficulties and complaints regarding their management. Hence, it might be expected that historical and cultural values will not be sufficient for tree preservation.

As for sacred trees, although the shrines and temples are trying to protect them, they are being lost due to lack of ecological considerations and deterioration of the surrounding environment, as seen in Tokyo (Poggendorf et al., 2007). Conversely, trees with historical and cultural value, including sacred trees, can be preserved by providing the support of an ecological approach for the system. Omoto (2016) also pointed out that the existence of an animal and/or plant species that symbolizes the region, called a flagship species, could be the basis for encouraging collaboration among various stakeholders in conservation activities. Conversely, however, Lynne et al. (2018) pointed out that sacred species only occur in abundance in sanctuary areas. Differing views that have been derived according to definitions of "religion" and "faith," which are affected by time and place, are unlikely to achieve a unified approach (Fujiwara, 2018). The impact of historical and cultural values on conservation depends on the situation and the influence of the historical and cultural values in that region; therefore, even if historical and cultural values are drivers of preservation at the present time, there is no guarantee that they will continue to be effective in the future.

Regarding long-term effects, it has been reported that the tree-planting plan, which had been proceeding smoothly under the leadership of religious organizations, came to a halt after the death of the leader (Ishinomori, 2019). Although our survey merely provides a picture of the awareness of the operators of the preserved tree system at a particular time, it also points to future research prospects for a more dynamic, long-term survey.

We would like to express appreciation to the operators of preserved tree system, the Nagoya City Green Land Business Division, and the Shizuoka City Green Policy Division. We also thank Yui Sunano, lecturer at Hiroshima Jogakuin University.