2021 Volume 38 Pages 25-42

2021 Volume 38 Pages 25-42

This study takes on the problem of how small and medium-sized start-up companies grow in matured or shrinking markets. It examines the case of BørneLund, a Japanese company that has achieved notable development by importing and selling European toys purported to be useful for children’s growth and education. The investigation is conducted from a perspective of “historical confluence,” which draws attention to a chance encounter between outcomes of activities carried out by multiple organizational entities. As a result of the investigation, the study reveals that the company’s exceptional development was made possible under the circumstances in which the company’s efforts to establish an inimitable business strategy encountered unintended consequences of Japanese educational policies: That is, Japanese middle-class families accelerated their investment in early childhood education, enhancing their interest in educational toys. The study indicates that even in a shrinking market there is a possibility that a small-sized start-up company can grow on the conditions that (1) the company makes proactive efforts to establish its original business model and that (2) the company’s efforts become confluent with unintended consequences of government policies that are not directly aimed at the company’s business.

This study deals with the historical process of the development of a Japanese company, BørneLund. The name means children’s forest in Danish. Separated from a company engaged in selling Danish playground equipment to nursery schools and kindergartens, BørneLund was established as an independent company in 1981. For around twenty years after its foundation, the company specialized in importing and selling basic European toys. After the turn of the century, it extended its business, embarking on the designing and running of indoor playground facilities. Engaged in a business field concerning children’s play, the company has confined its business within the domestic market. Since the beginning of the 1990s in particular, demands for toys and playground equipment in general have been sluggish in Japan. Nevertheless, however, BørneLund’s revenue increased by around three times from 1.8 to 6.2 billion yen between 1999 and 2018. Having started with only one store, the company now has more than seventy stores as of the end of 2020.

The toy industry has a long history, and both economic and business historians have long conducted researches on the subject. From the beginning of the eighteenth till the early twentieth century, German and French companies fought each other over hegemony in the industry1 (Theimer 1998; Mori 2017) .The outbreak of WWI gave Japanese toy companies momentum to enhance their presence. Although the Japanese toy industry declined during WWII (Tanimoto 2013; Toy Journal 2003), it started to develop again during the 1950s. Japanese toy companies increased their production and export during and after the1960s, and then Japan became the world’s top toy exporter (Toy Journal 2003). In 1972, however, Hong Kong replaced Japan as the top toy exporter (Yan 1990; Takayama and Japan Toy Culture Foundation 2000). The toy industry in mainland China also enhanced its presence in the world market2 (Marukawa 2011). Since the beginning of the 1990s, toy-related markets in Japan have shrunk on account of the declining birthrate and economic stagnation. In response, Japanese toy companies accelerated mergers and alliances in the latter half of the 1990s with an aim to complement each other in their business domains and strengths. A typical example of this is the establishment of Bandai Namco Holdings of 2005, under which the managements of Bandai and Namco were integrated (Kondō 2000). Those enlarged Japanese toy companies concentrated their business resources on the designing and selling of toys collaborated with contents and characters of anime and comics with a view to target growing overseas markets. This has been a typical survival strategy adopted by present-day Japanese toy companies. Little is known, however, about small and medium-sized Japanese toy companies that have achieved development in the matured domestic toy market without resorting to mergers and alliances. BørneLund is a representative example of those companies. By examining such a case, this study makes contributions to the investigation into the broader problem posed for business historians: That is, how small and medium-sized start-up companies grow in matured or shrinking markets.

This study is based on various historical materials. In particular, it has recourse to BørneLund’s public relations magazine titled Asobi no mori [Forest of play], which is distributed mainly to the company’s registered customers. The magazine is very useful for this investigation, since it contains much information on the company’s policies, ideas, and activities. Therefore, the investigation makes use of the magazine’s issues from the past twenty years. In addition, it also fully utilizes other materials, including articles posted on major newspapers and journals, books, movies, pictures, and many kinds of statistical data. Moreover, four persons from the company, including President, have been interviewed, and their words are analyzed. The consistency of evidence provided by those various research materials is carefully cross-checked in the course of the investigation. Then, hermeneutic interpretation is conducted, with historical contexts taken into account. By so doing, history is reconstructed (Kipping et al. 2014; Wadhwani 2016).

In this study, the reconstruction of history is carried out from a perspective of “historical confluence” (Sakai 2021). Viewed from this perspective, activities of an organization chosen as a research subject, or “protagonist,” encounter and become confluent with activities of other organizations in certain historical contexts. As a consequence, various changes occur with regard to the organizations. Researchers who adopt this point of view shed light not only on the protagonist but also on other historical actors that crucially affected the historical phenomenon in question. In doing so, they analyze their activities in relation to historical contexts. In this way, it is possible to provide a more appropriate historical account of a company’s development, instead of a simple success story ending with deus ex machina (Sakai 2019; Sakai 2021).

First of all, this study traces a process in which BørneLund constructed its business strategy as a unique system of activities (Porter 1996). According to the paper by Porter, the objective of a company’s strategy is not so much to improve operational efficiency as to establish an original system of activities that place the company in a position that is attractive and valuable to customers and different from rival companies. Even if individual activities seem simple, the whole system comprising intricately intertwined activities is a complicated entity. It can be a source of the company’s competitive advantage, because it is difficult for rival companies to imitate it. To highlight a process in which a company actively created a strategic system comprising mutually dependent activities provides an instructive viewpoint to understand the development of small and medium-sized companies.

Second, as an important actor that influenced the development of BørneLund, this study draws attention to Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (hereafter, MEXT), which is responsible for Japanese educational policies. Although this ministry had been called Ministry of Education, Science and Culture before the 2001 central government reform, the abbreviation, MEXT, is used in this study regardless of period. Conventionally, researchers on the modernization of the Japanese economy have regarded, as a crucial actor, Ministry of International Trade and Industry (present-day Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry; METI, hereafter, regardless of period), which is responsible for industrial policies. However, the author has made a hypothesis, as a result of a pilot research based on the analysis of newspaper articles, that a social trend, which was generated not directly by METI’s industrial promotion policies but as an unintended consequence of MEXT’s policies to improve education and admission systems, gave a positive influence on the strategy and development of BørneLund.

The structure of this study is as follows. At the beginning of the next section is presented an overview on the current state of BørneLund. Then, the process of the establishment of its business strategy is traced regarding two successive periods: (1) From the company’s foundation till the establishment of its toy selling business (1977-2001); (2) From the commencement of its playground designing/running business till the present day (2002-2020). In the third section, changes of MEXT’s educational policies and their influences on BørneLund’s business are analyzed. In Conclusion, BørneLund’s history is re-comprehended from a theoretical point of view, and academic contributions of this study are clarified.

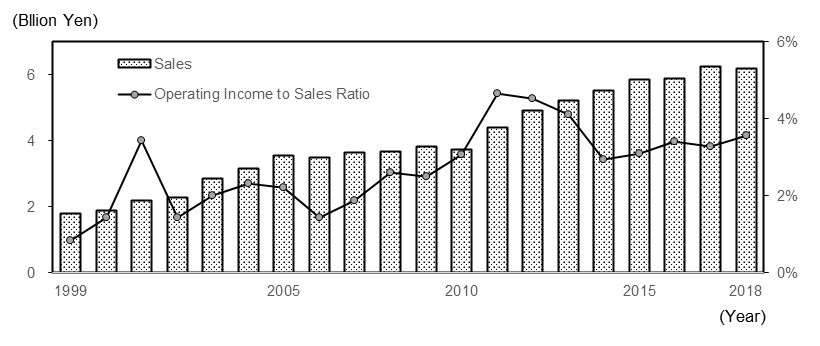

For about two decades after its 1981 foundation, BørneLund specialized in importing simple toys from Europe and selling them in the domestic market. Figure 1 shows a typical example of toys traded by the company. After the turn of the century, the company embarked on a domestic business of designing and running playgrounds with large equipment imported from Europe. The company named the playground KID-O-KID. As Figure 2 indicates, both sales and operating income to sales ratio of the company almost always increase throughout the period after 1999, from which year onward data are available. This development does not correspond to the general trend of the Japanese toy and amusement facility industries. The size of Japan’s domestic toy market (value of manufacturers' shipments) decreased from 850.2 to 640.2 billion yen between 1996 and 2019.3 As for the amusement facility industry, the market size contracted from 649.2 to 520.1 billion yen between 2005 and 2019.4 This section examines reasons why BørneLund was able to achieve such exceptional development, focusing first on the process in which the company created its business strategy.

Figure 1: A typical example of toys that BørneLund has sold

Source: BørneLund.

Figure 2: Long-term trends in BørneLund’s sales and operating income to sales ratio

Source: Made by the author on the basis of materials provided by BørneLund.

Nakanishi Masayuki, the founder of BørneLund, had been Marketing Director of a trading company dealing with European brand toys, before establishing, in 1977, a company that sold large playground equipment imported from Denmark to nursery schools and kindergartens in Japan. Then, having conceived a plan to set up a company specializing in small toys, he and his wife, Nakanishi Hiroko, co-founded BørneLund in 1981. Nakanishi Hiroko, who was promoted from Vice President to President in 1994, has been deeply involved in the company’s management from the outset.

In order to understand the uniqueness of BørneLund’s strategy, it is instructive to grasp the historical contexts of the child’s play business in Japan. After the end of WWII, Japanese toy manufacturers enjoyed profits from the advent of a society based on mass production and mass consumption. During the 1960s, character toys collaborated with anime and comics were brought to the market one after another, which children around the country consumed. The same structure continued to exist into the 1970s.

Under those circumstances, BørneLund adopted a policy not to deal with any character toy. While importing toys that were safe, simple, and unaffected by fleeting trends (for example, blocks and wooden puzzles) from long-established European manufacturers, the company sold them to parents who were relatively well-off and enthusiastic about their children’s education. In doing so, the company publicized its toys’ educational value, emphasizing their good effects for children’s intellectual training. That was a unique strategic position BørneLund chose to take. In Europe, such toys were not unusual, and their value was commonly recognized. Whereas in Japan where mass production and mass consumption of character toys were prevalent, BørneLund’s business was original and unique. It was thanks to the connections with long-established European manufacturers Nakanishi Masayuki, the company’s founder, had built while working for the trading company that the business of importing those toys was made possible. However, the company's basic principle to be critical of Japanese character toys and highly evaluate European toys was largely based on Nakanishi Hiroko's interpretation of the social context at the time. The following are her remarks on this subject.5

At that time, there was only iron-made playground equipment in Japan. As for toys, it was the heyday of character toys. […] Any way, all that amused and attracted – I dare not say, “deceived” – children by whatever means were considered good toys. In fact, such type of toys were selling. “What sells is good.” People were thinking that way. In those days, department stores and wholesalers, for instance, set aside unmarketable goods such as educational toys we brought in. In their view, goods like ours were not worth handling. [The adverse wind was] so strong […]. However, we had been trading with many European toy manufacturers. When we looked at toy markets in Europe, we found that they had been producing a lot of toys different from character toys. They were seriously engaged in toy-making, giving thoughts on how children would react to their toys, what children’s experiences with their toys would be like and how their toys would serve for the building of the relationships between parents and children. (Interview with President Nakanishi made by the author on February 19, 2020)

Believing that toys were indispensable tools for children’s growth, she became deeply involved in BørneLund’s decision-making concerning the types of toys the company should handle. She was of the opinion that when choosing right toys for children it was important to take into consideration their growth stages. For example, she thought that babies needed to be given toys suitable for developing their basic physical abilities such as “grabbing” and “picking.” For children over the age of four, she recommended toys useful for the “development of creativity.” Nakanishi Hiroko created such original standards on the basis of her own childcare experience and her knowledge acquired through her trading experience with European toy manufacturers.

In its early years, however, BørneLund’s toys did not sell well. As is mentioned in her remarks quoted above, it was the common view in the Japanese toy industry at the time that toys that were not collaborated with anime and comics would not sell. Therefore, wholesalers and retailers were not willing to promote BørneLund’s toys. In such a situation, the company asked banks for loans, explaining its business to them. Thanks to the bank loans, BørneLund was able to open its first company store in Osaka in 1986. By the end of 1991, the number of such stores that were directly managed by the company had risen to sixteen. By establishing those company stores, BørneLund became able to convey straightly to its customers its policy to handle only the type of toys that would serve for children’s growth and education. The company’s policy was well received by customers enthusiastic about their children’s education. Conceiving of BørneLund’s toys as a kind of teaching aides, or learning materials, they became eager purchasers of the company’s goods.6

At those stores, in addition, the company tried to create a new type of sales floors, allowing children to play with displayed toys even before purchasing them. At ordinary Japanese toy stores, toys were displayed inside glass cases or boxes lest children play with displayed goods that were for sale. However, BørneLund adopted the opposite tactic, making a different type of sales floors in its company stores. Further, the company urged its salespersons to actively help children play with displayed toys. For that purpose, the company strategically employed, as salespersons, those who were familiar with how to take care of children: for instance, former nursery teachers and those with child-raising experience. When BørneLund’s customers, who were parents of children, made purchase decisions, they not only checked toys’ educational effects but also made sure whether their children actually had fun with them.

The quality of salespersons was crucial for letting both parents and children know the fun of playing with BørneLund’s toys as well as their educational effects. The company, therefore, developed a systematic training system for its salespersons. At the company, salespersons were called “Instructors,” who were classified into three categories according to their abilities. In order to be promoted to a higher category, an “Instructor” had to undergo training and pass an examination. Those belonging to the highest category, “master,” assumed the role of, for instance, giving advice to customers about child-raising and proposing an appropriate playing environment for children. As a result of these measures, it became a usual occurrence that parents and children who visited a company store spent hours in the sales floor without feeling bored.

Furthermore, BørneLund published a free magazine, Asobi no Mori [Forest of play], several times a year, providing information about child’s growth and development, benefits of play, the company’s goods and services, cases of child-raising and parenting in Europe.7 It was repeatedly emphasized in the magazine that, in European societies, children were cared for with more respect and people had a more advanced understanding of the importance of child’s play than in Japan where adults’ viewpoint had precedence. It was maintained time and again in the magazine that the European type of understanding should be predominant also in Japan. In addition, the magazine allotted many pages for scientific essays on child play’s benefits contributed by pediatricians, pedagogy experts and psychologists.

In the 2000s, other Japanese toy companies that have recognized business potential of educational toys began to enter the competition.8 That move by giant toy companies raised the sales of educational toys to 135.5 billion yen in fiscal 2001, around 5 percent increase from the previous fiscal year. The growth was made under the circumstances in which the total toy sales decreased by around 0.5 percent to 716.8 billion yen during the same period.9 However, the uniqueness of BørneLund’s business strategy was not overshadowed by those large newcomers, and therefore, the company continued to develop after 2000. The company constructed an integrated strategy system comprising various elements such as close ties with European toy manufacturers, the training of salespersons with a deep understanding of children and their play, the preparation of sales floor where children could spend a fun time and supply of information about its values and ideas to its registered customers. Although its rival companies were able to sell educational toys as such, they were hardly able to build the type of integrated strategy system BørneLund created.

2. Expansion to the playground equipment business and further development: 2002-2020As BørneLund’s reputation grew, it received an increasing number of orders for large playground equipment from nursery schools and kindergartens. By the end of 1991, the company had already had two thousand nursery schools and kindergartens as its toy customers. From 2002 onward, the company opened its large-scale flagship stores one after another, displaying and selling, in addition to toys for general consumers, large playground equipment for organizations engaged in childcare services.

Know-how about the large playground equipment business as well as about the creation of the attractive sales floors acquired by the company served for its business expansion. In 2002, BørneLund held a limited-period event in Kitakyushu City, setting up its first indoor playground facility. Various kinds of playground equipment were placed in a space of 7,000 square meters in accordance with themes and child’s development stages, so that children could experience various kinds of play. Without any anime stage show or state-of-the-art game, this event attracted 360 thousand people, which far exceeded expectations.

Given confidence by the event’s success, BørneLund opened, in succession from 2004 onward, large amusement complexes called “BørneLund Asobi no Sekai [the world of play].” The complex comprised a conventional company store dealing with various kinds of toys and “KID-O-KID,” a pay playground for children between the ages of zero and twelve. At KID-O-KID, a child could, for example, jump on a big air mat, or to take another example, get into a cylindrical play equipment and move forward, rolling it him/herself. At each KID-O-KID, employees called “Play Leaders” were engaged in roles such as giving advice to both parents and children regarding how to handle the equipment and introducing shy children to a play group.

KID-O-KIDs attracted a lot of visitors from the outset. According to the records of Yokohama Minatomirai KID-O-KID regarding the year 2004, 450 to 500 people visited the facility during weekdays and more than a thousand turned up on weekends. The number of visitors continued to rise rapidly: a little less than 0.3 million in 2007; 1.17 million in 2010; and around 2.7 million in 2016. At most KID-O-KID facilities, a toy shop was annexed, so that parents could buy toys on the spot whenever they found that their children were having fun with them.

KID-O-KID became popular firstly because BørneLund’s concept that the company would contribute to children’s development and education by committing to the toy business was well received by customers enthusiastic about their children’s education. While promoting its concept, the company repeatedly emphasized a scientific finding that physical strength of children, which correlated with their brain development, was declining in Japan because there were fewer and fewer places in which children were able to do exercise safely. The company also had university professors conduct researches concerning physical strength and movements of children who played at KID-O-KID. On the basis of such researches, the company stressed that KID-O-KID was a facility useful for children’s physical improvement and brain development. The second reason for the popularity of KID-O-KID was the social situation in which places for children to play freely were becoming scarce especially in urban areas.10 Third, KID-O-KID also had a merit of providing real fun to children. In a newspaper article published in 2009, for example, an eight-year-old “regular visitor” says, “[KID-O-KID] never bores me.”11

Since KID-O-KID made a large social impact, companies emerged that sought to imitate its business model.12 However, they were able to do so only superficially. Since its foundation, BørneLund has learned logic behind child’s play from toy and play equipment manufacturers in Europe as well as from researchers both in Japan and abroad. On the basis of knowledge acquired in that way and acquired through its own experience, BørneLund has made hypotheses and tested them on its sales floors. As a result, the logic behind how each play space and play equipment gave benefits to children was shared by all the company staff and even among “Play Leaders” at each play facility. It was this characteristic that made KID-O-KID an attractive place for customers enthusiastic about their children’s education. Therefore, it was not unusual that no small number of visitors came to the facility on a weekday morning, had lunch outside and then came back and spent hours there until the closing time. At other play facilities run by rival companies, however, there were elements that could not be considered useful for children’s development: For example, there were certain types of play equipment that moved, or were used, only in fixed ways; There were too many rest stations for adults; The staff were doing nothing more than keeping eyes on children.

As KID-O-KID’s reputation spread among parents with little children, an increasing number of commercial complexes (shopping malls and department stores) whose customers comprised parents and children asked BørneLund to become a tenant and open its facility. This trend continued into the 2010s, with more variety of business and social entities, including car retailers, administrative offices, condominiums, restaurants, cafes and even temples, seeking to introduce children’s playgrounds produced by BørneLund.

BørneLund’s history examined in the previous section may give an impression that the company’s successful development was a result of its own efforts based on its original business strategy. In reality, however, there were other factors. For instance, as was mentioned, the company’s success was achieved under the social circumstances in which the shortage of children’s playgrounds was becoming serious together with the decline in the birthrate. In addition to this social factor, this section examines consequences of educational policies implemented by MEXT, demonstrating that a series of Japanese educational policies designed for the improvement of school education and admission (entrance examination) systems produced unintended results. That is, they effectively accelerated Japanese middle-class families’ additional investment in child education, while expanding related markets. During the process of this social change, middle-class families seeking better education for their children regarded BørneLund’s toys and play facilities as suitable for their purpose and actively purchased and utilized them.

As the Japanese economy developed after the end of WWII, middle-class parents’ desire to send their children to universities intensified (NHK Hōsō Yoron Chōsajo 1982). With the increase in the tertiary education enrollment rate, the term, kōgakureki [high educational background], has come to mean to enter prominent universities. In Japanese society, high educational background in this sense has, in fact, given advantage in terms of job-hunting, promotion within the company and income level (Tachibanaki and Yagi 2009; Tachibanaki and Matsuura 2009). With this recognition, children of Japanese middle-class families have taken part in the fierce competition to enter prestigious universities in the hope of social advancement.

MEXT designed educational policies to mitigate the fierceness of the competition. Although MEXT tried to lay importance on individual personality and to diversity the entrance examination system during the 1970s (Nakazawa 2007), the tendency among prominent universities to focus on academic ability did not change, and the fierceness of entrance examinations was not alleviated.13 During the 1980s, the Japanese government advocated a reform of post-war education, and in 1984, Provisional Council on Educational Reform under the direct jurisdiction of Prime Minister adopted the principle to cherish individual personality (Andō and Jufuku 2013). Accordingly, MEXT criticized, once again, the uniformity of the conventional education that was mostly aimed at entrance examinations.14 As a result, the recommendation-based entrance examination system that placed more importance on individual personality than academic ability spread further (Nakamura 2011; Nakazawa 2007). At prominent universities, however, the number of enrollments allotted to recommendation-based examinations remained relatively small. Therefore, the tendency to focus on academic ability hardly changed. In the meantime, the so-called second-generation baby boomers, who had been born between 1971 and 1974, began to take entrance examinations in the late 1980s. Consequently, the fierceness of the competition to enter prestigious universities intensified even more, with brand names of such universities permeating further and deeper throughout the society.15

During and after the 1990s, MEXT implemented educational policies designed to make the educational system and entrance examinations more adaptable to changes of the times. In particular, the systematized educational method focusing on memorization was targeted as a source of problems in Japanese society faced with economic stagnation. In consequence, the idea of yutori [pressure-free education] rapidly gained validity. During and after the mid-1990s, in addition, the term, ikiru chikara [the power to live], the meaning of which included an ability to solve problems by him/herself, rich humanity and so on, became a key word of MEXT’s educational policies. In order to cultivate “the power to live,” MEXT reduced classroom hours in primary and secondary education. At the same time, however, a group of large corporations began to publicly criticize Japanese higher education of being responsible for the lackluster performance of Japanese companies. Insisting that the cause of the low economic growth resided not in companies themselves but in the educational system and particularly the university education, they urged the government to implement a fundamental reform (Aoki 2021).

After the turn of the century, the Japanese government placed top priority on, among others, the rebuilding of education, stressing once again its intention to rectify the conventional systematized education focusing on knowledge-cramming. However, faced with the result of the 2003 PISA (Program for International Student Assessment), in which Japan lost positions, the public opinion severely criticized the idea of yutori for being responsible (Andō and Jufuku 2013). In response to this criticism, MEXT declared “datsu-yutori [post-pressure-free education]” (i.e., improvement in academic ability) in 2005, proclaiming its policy to improve curriculum and increase classroom hours. However, there still remained the persistent belief that “the power to live,” which was not directly related to academic knowledge, was indispensable for Japan to win the international competition. As a result, a rather complex situation emerged in which “post-pressure-free education” and “the power to live” were both set as pillars of the country’s educational policy (Honda 2020).

In the meanwhile, MEXT continued to press forward, throughout the 2000s, with its policy to diversify the university admission system. Eventually, however, it was only on middle- and low-ranked universities that the policy had effects. Since those universities were having difficulties in filling their enrollment capacities due to the declining birthrate, to increase opportunities to recruit students through paths other than academic ability examinations was an attractive method.16 However, with regard to top-ranked prominent universities that had always been popular, the tendency to lay importance on academic ability examinations remained more or less unchanged relative to middle- and low-ranked ones. (Nakamura 2011)17

The series of educational policies implemented by MEXT created a situation in which abilities required for children became diversified and complicated. Among various abilities required for Japanese children, top priority had previously been placed on academic ability. In the 1980s, however, MEXT began to stress that future Japanese children should develop individual personality and that they would not be able to survive in the international competition unless they acquired the “power to live.” The “power to live” was an ambiguous ability not directly related to academic ability (Honda 2020). At the same time, however, MEXT continued to demand that high academic ability should also be developed, although it temporarily prioritized “pressure-free education.” In reality, the social situation in which high academic ability was crucial for entering a prestigious university and making social advancement remained mostly the same.

This diversification of abilities required for children produced serious concern and confusion especially among middle-class families anxious to make social advancement through education (Tachibanaki and Yagi 2009). At the time when only academic ability was valued, what middle-class families had to do was the systematized knowledge-cramming. That was hard, but what had to be done was simple and clear. However, as required abilities became diversified and complicated, the “right” thing for middle-class parents to do for their children became ambiguous.

Japanese middle-class parents tried to cope with this increased uncertainty by providing their children with supplementary education in a variety of ways from the earliest possible time. This point is confirmed by data gathered from surveys conducted by a bank in 1987, 1989, 1990 and 1991, which reveal proportions of children receiving supplement education (for example, attending after-hours tutoring school and taking correspondence courses) by age group (The Sanwa Bank 1991). The bank implemented these surveys, through the drop-off and pick-up method, on customers living, with their children, in the Tokyo and Osaka metropolitan areas. The data from the surveys are not suitable for grasping the general trend in Japan as a whole because of sampling bias. However, these data, which concern bank customers living in urban areas with their children, are useful enough for the purpose of this study.18 The analysis of the date shows that proportions of children receiving supplementary education rise throughout the period in question regarding all age groups from kindergarteners to junior high school students. Among them, the increase is especially eminent with regard to kindergarteners and children in lower grades of elementary school. The percentage of the former surges from 4.4 to 21.5 percent during the period, and the latter, from 27.6 to 36.2 percent.19 These data indicate a trend in which families living in urban areas were showing growing enthusiasm for their children’s education during the period. The tendency continued into the 1990s. According to a 1998 newspaper article, the size of the market related to child education grew from 167 to 202 billion yen between 1992 and 1996. In addition, under the social circumstances in which the systematized education had long been criticized, a type of child education including elements of “play,” instead of knowledge-cramming, came to be desired strongly during the 1990s, and the validity of such education became widely accepted.20

Parents keen on child education also began to opt for toys with educational effects rather than character toys that only amused their children. This change buttressed BørneLund’s activities and in particular its toy business. For example, a 1991 newspaper article says: “Parents generally want to give the best education to their children regardless of how much it costs. Toys have become important educational tools, and now those with real educational effects are in need”21 A 1999 newspaper article also quotes a comment by a toy store manager: “What serve for intellectual training sell better than mere character goods.”22 In addition, the same article quotes a comment by a 31-year-old woman who had bought her year-and-a-half old son a toy for intellectual training: “Whatever it might be, I wanted something good for my son’s education.” Middle-class parents’ enhanced interest in child education also affected the success of BørneLund’s indoor playground business (KID-O-KID) that started in the 2000s. As was mentioned, the company had pointed out and stressed, as a social problem, the decline of Japanese children’s physical strength that correlated with their brain development, and told to its customers that to let their children play at KID-O-KID was a solution to the problem. BørneLund repeated this line of reasoning, and its core customers were attracted and convinced by it.

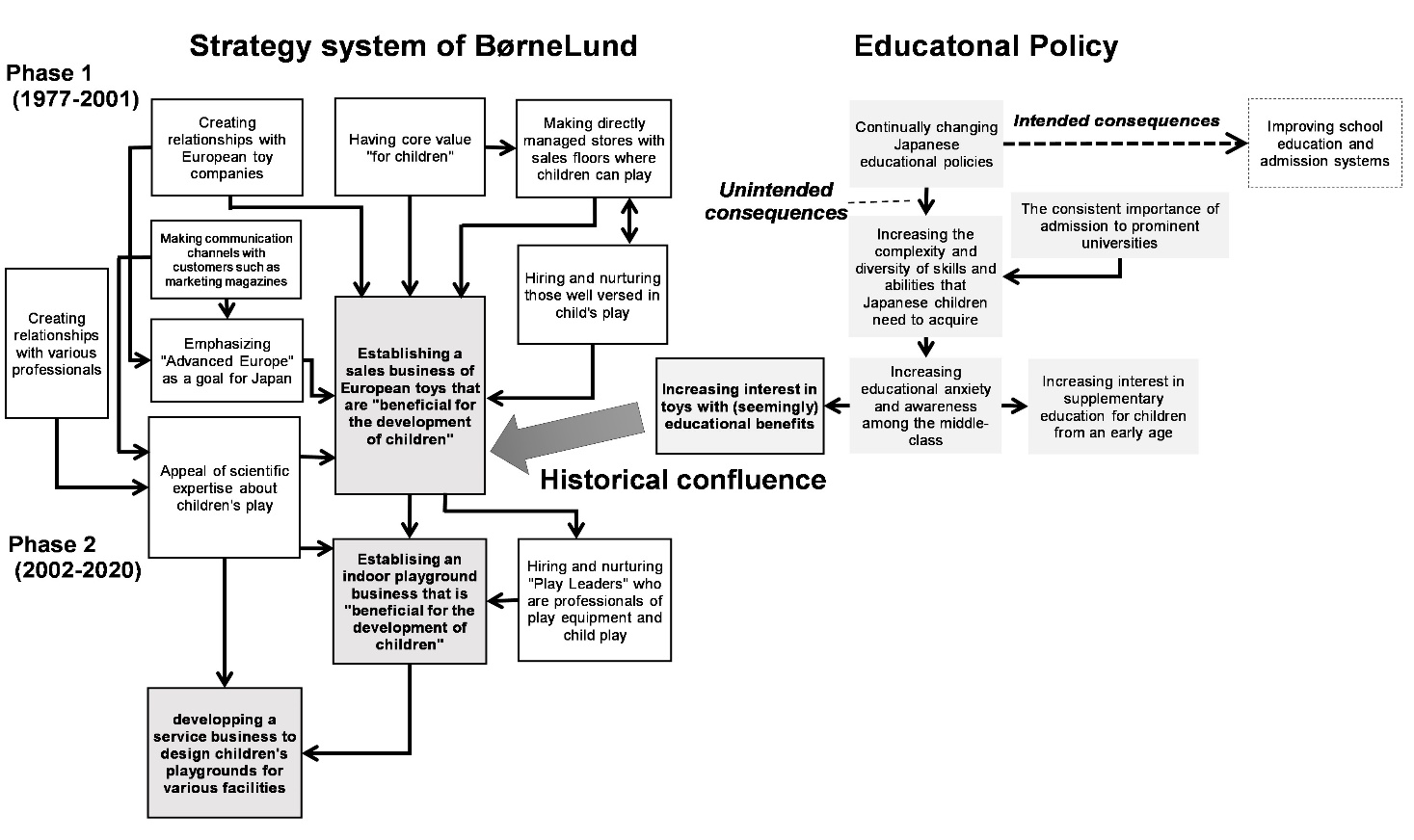

This study has examined and revealed the social background against which BørneLund has achieved exceptional development in the already matured Japanese toy industry. It has been conducted from the perspective of the “historical confluence” of the business strategy created by the company and the unintended consequences of Japanese educational policies. Figure 3 presents a general overview.

Figure 3: The Historical confluence of BørneLund’s business strategies as a unique activity system and unintended consequences of Japanese education policies

Source: Made by the author.

On the left side of Figure 3 is shown BørneLund’s business strategy as an activity system. While Porter’s original activity system map shows a combination of synchronic activities (Porter 1996), Figure 3 gives a diachronic overview of how various activities of the company have formed its core business. In Phase 1 covering the period between the company’s foundation and the early 2000s, BørneLund took the strategic position to import and sell European toys at the time when character toys were in their heyday. Behind the company’s strategic move lay its philosophy, “For Children,” and the close relationships it had built with long-established toy manufacturers in Europe. In order to let its customers know the value of its toys, BørneLund opened directly-managed stores and provided sales floors in which children could play with its toys even before purchase. In addition, the company utilized scientific knowledge of experts and experience of its employees familiar with children’s play in an effort to effectively propagate the educational value of its toys. Further, the company repeatedly emphasized that in European countries the relationship between children’s play and their growth has always been recognized. In Phase 2 covering the period during and after the 2000s, BørneLund embarked on the indoor playground business, continuing to adopt the same basic strategy. Making use of research results gained by experts, the company told Japanese parents that physical strength of children, which correlated with their brain development, was declining and that KID-O-KID would provide a solution to the problem. Although some companies tried to imitate BørneLund’s business, the company was able to sustain the uniqueness of its business since it had constructed a strategic system consisting of mutually dependent intricate elements.23

However, the historical background of BørneLund’s development cannot be properly grasped as long as attention is drawn only to the company’s efforts to build its difficult-to-imitate strategic system. It is by taking into account unintended consequences of Japanese educational policies which became confluent with the company’s effort that the historical background can be more properly apprehended. On the right side of Figure 3 are shown changes in educational policies. When educational policies were implemented in Japan, the primary intention was to cope with problems concerning school education and admission systems and to respond to the needs of the times. Various revisions were made, especially during and after the 1990s, to the traditional educational policies, and abilities and skills required for children became diversified and complicated. As a result, it became difficult for middle-class families to find a clear educational goal, that is, a clear path to social advancement. Eventually, their anxiety over the ambiguity drove them to accelerate their investment in their children’s education. Since BørneLund had propagated, through various channels, educational value of its goods and services, parents enthusiastic about child education actively purchased them. This historical case indicates that even if the market condition is stagnant, small and medium-sized start-up companies can achieve strong development provided that unintended consequences of government policies exert a positive influence on companies’ efforts. However, chance favors only the prepared mind. Therefore, accumulated efforts for building a unique strategic system is indispensable to gain support from unintended consequences of government policies.

Did MEXT intend such influence when it implemented educational policies? Some may think that MEXT, to some extent, intended to expand and improve home education because “small government” and “self-responsibility” were the basic principles of the educational system during and after the mid-1980s. However, it is not plausible that MEXT had anticipated that middle-class families’ growing concern over their children’s education would lead to the increase in their investment in early childhood education, producing ripple effects on business related to children’s play. Therefore, it is proper to regard the educational policies’ positive effects as unintended consequences.

Although this study has limitations such as a shortage of primary materials concerning educational policies, it does contribute to this research field in some respects. First, this study has advanced, a step further, managerial and industrial history research on the Japanese toy industry. The most recent researches on Japanese companies in this industry have shown that they have adopted, in the face of the shrinking domestic market, a surviving strategy to export toys collaborated with anime and comics to the international market while enlarging themselves through mergers and alliances (For example, Kondō 2020). This investigation, on the other hand, is a case study of a relatively small-sized company that sought to find its own surviving space in the shadow of those giant corporations.24 Instead of following the trend those giant corporations had created, BørneLund adopted a strategy to import goods and services from overseas, add new meanings and values to them and sell them in the domestic market. The company’s strategy gives a very instructive lesson to many small and medium-sized companies in Japan. During the 2000s, in addition, BørneLund embarked on a service business of designing and running children’s playgrounds on the basis of know-how it had acquired from its toy business. The company’s activities during and after the 2000s also give a hint of a path to survival to small and medium-sized companies in the matured post-industrial society.

This study also makes a contribution to historical research on the relationship between government policies and company activities in Japan. In this research area, it was once emphasized that METI’s industrial policies exerted a positive influence on Japanese companies and on the Japanese economy as a whole (For example, Morikawa 1976). Although some researchers presented a rather optimistic outlook based on this positive influence (for example, Hollerman 1988), the Japanese economy in reality went down during and after the 1990s. Therefore, mainstream researchers have come to take a critical view of Japanese industrial policies (Drucker 1993). In addition, the critical stance toward the simple presupposition that METI’s intentions would be realized as planned has produced some outstanding studies on Japanese companies and industries that shed light on “unintended consequences of government policies” (For example, Shimamoto 2001). Further, this research trend has developed in the direction of analyzing interactive relationships between industrial policies and company activities in Japan (For example, Hirano 2013).

In line with this research trend, this study has highlighted unintended consequences of government policies. In addition, the study has also emphasized interactive relationships between government policies and company activities. During the 1990s, large Japanese companies demanded that politicians implement tertiary education reform, attributing the responsibility for the country’s economic downturn to the existing higher education system. Such action affected, to some extent, the subsequent educational reform policy designed by MEXT (Aoki 2021). The educational reform prompted middle-class families’ investment in education, affecting not only companies in the educational industry but also those in the toy industry that were closely related to education. It is an interesting phenomenon in that companies totally different from the ones that demanded the reform policy were eventually affected by the policy in a positive way.

By dealing with educational policies, this study has also expanded the research area, which had previously been limited to industrial policies. Educational policies are carried out, of course, with an intention to improve education. As has been demonstrated in this study, however, they sometimes produce, as their unintended results, opportunities (or threats) to a wide variety of companies related to children by exerting effects on parents’ educational investment. Business history would be enriched, if this perspective of “unintentionally produced economic effects of non-economic policies” is added. By doing so, we can make a progress toward a better understanding of complicated relationships between the state and companies.

Acknowledgements: This work was supported by KAKENHI 21H00738.

1 As for the British toy industry in the nineteenth century, see, for instance, Brown (1990).

2 As for the US toy industry during the 1970s and 1980s, see, for instance, Walsh (1992).

3 Yano Research Institute, Research Express: Results of a survey on the toy market 2008 (January 30, 2009). Retrieved June 13, 2021, from Nikkei Telecom, https://t21.nikkei.co.jp/g3/CMN0F21.do. Yano Research Institute, Researching the toy market 2020 (2021). Retrieved June 13, 2021, from https://www.yano.co.jp/press-release/show/press_id/2619.

4 CAPCOM, Annual report 2010 (2010). Retrieved June 13, 2021, from https://www.capcom.co.jp/ir/data/annual_2010.html. CAPCOM, Annual report 2020 (2020). Retrieved June 13, 2021, from https://www.capcom.co.jp/ir/data/annual.html.

5 She had made a similar comment during the 1990s. See, “BørneLund Shachō Nakanishi Hiroko-shi – Chiiku gangu o yunyū (Kigyōjin ōini kataru) ”[Ms. Hiroko Nakanishi, President of BørneLund – Importing toys for intellectual training (Interviews with entrepreneurs)] , Nikkei Ryūtsū Shimbun [Nikkei Marketing Journal] (September 20, 1997): 3.

6 “BørneLund kihon gangu dake hanbai kyōzai to shiteno hyōka eru (Kōkando kigyō asu eno chōsen” [BørneLund, Selling basic toys only, Highly evaluated as teaching aids (Popular companies, Challenge for tomorrow)], Nikkei Sangyō Shimbun [Nikkei Business Daily] (April 30, 1991): 19.

7 “Chiiku gangu, oya ni oshieru – TOMY BørneLund, Muryōhaifu sassi ni jōhō mansai” [Toys for intellectual training, Teaching parents – TOMY, BørneLund, A lot of information in free magazines], Nikkei MJ (August 13, 2002): 3.

8 See, for example, “Kodomo no eigo wa omocha de manabu – Shaberu puzzle ya chikyūgi, Kaigaisei mo aitsugi tōjō” [Children learn English with the aid of toys – Talking puzzles and globes, Imported toys are also being sold one after another], Nihon Keizai Shimbun [Japan Economics Newspaper] (May 16, 2003): 31.

9 “Chiiku gangu, oya ni oshieru – Takai kōnyū tanka, Igyōshu mo sannyū” [Toys for intellectual training, Teaching parents – High purchase unit price, Companies in different industries are also entering the market], Nikkei MJ (August 13, 2002): 3.

10 See, for example, “Kodomo no asobiba nai, hahaoya no hansū ijō ga nayami shien dantai chōsa <Seibu>” [According to a survey conducted by a support organization, more than half of the mothers are concerned that there is no playground for their children <the western district>], Asahi Shimbun (chōkan) [The Asahi Newspaper (morning edition)] (January 7, 2000): 25.

11 “KID-O-KID: Mitakoto mo nai yūgu ga ippai (Odekake nabi)” [KID-O-KID: Full of play equipment you have never seen (City navigation)], Nihon Keizai Shimbun (yūkan) [Japan Economics Newspaper (evening version)] (February 14, 2009): 7.

12 See, for example, “Game center, oyakozure de tanoshinde – SEGA chiiku bangumi, AEON gangu jiyū ni” [Please have fun at game centers with parents and children – SEGA: Toys for intellectual training; AEON: Play freely with displayed toys], Nihon Keizai Shimbun (June 29, 2001): 35.

13 The following video, for example, is instructive for an understanding of the social situation at the time. “Juken Season (Shōwa 51-nen 1-gatsu)” [The entrance examination season (The 51th year of the Shōwa period, January)], Chūnichi News, No. 1150-2. Distributed January 20, 2017. Retrieved September 4, 2021, from YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dEvlZlD0Ngw.

14 “Monbu-shō, nyūshi kaikaku mo fukume ankēto chōsa kaishi 2-man 8-sen nin taishō” [MEXT starts a questionnaire survey including questions concerning entrance examination reform. The number of targets is 28 thousand], Asahi Shimbun (chōkan) (May 2, 1989): 3.

15 See, for instance, “Gakkōkan sabetsu ga baito saki demo (Koe)” [Students are discriminated against on the grounds of school rank even at workplaces where they are doing part-time jobs (Voice)], Asahi Shimbun (chōkan) (March 13, 1988): 5.

16 See, for example, “Juken kankyō garari henka teiinware daigaku zou, igi usureru Ōbunsha moshi tettai” [The situation surrounding entrance examinations has changed radically. An increasing number of universities are having difficulty in filling their admission capacity. The Ōbunsha withdraws from its trial examination business, as it loses its social significance], Asahi Shimbun (chōkan) (November 10, 2000): 11.

17 See also, “Yutori to juken, betsubetsu de iika (Koe)” [Pressure-free education and entrance examinations: Are they two separate things?], Asahi Shimbun (chōkan) (September 20, 2000): 14.

18 BørneLund’s major business areas are city centers, and its main customers are parents.

19 Changes in the proportions by age group revealed in the four surveys are as follows. High school students (between the ages of 15 and 18): 45.5%, 33.3%, 47.9%, 39.1%. Junior high school students (between the ages of 12 and 15): 69.8%, 78.4%, 76.9%, 75.9%. Children in the upper grades of elementary school (between the ages of 9 and 12): 53.9%, 56.3%, 60.0%, 59.5%. Children in the lower grades of elementary school (between the ages of 6 and 9): 27.6%, 29.2%, 35.1%, 36.2%. Kindergarteners (between the ages of 3 and 6): 4.4%, 13.9%, 19.6%, 21.5%. The numbers of respondents as to the years 1989 and 1991 are, respectively, 744 (the response rate, 31.0%) and 647 (the response rate, 27.0%). As to the years 1987 and 1999, the numbers are not available. With regard to the 1991 survey, the average age of the respondents is 41.2 years old.

20 “Dai 5-bu kodomo o tsukuru (2) manabu yōji no mure – mienu mirai (Onnatachi no shizukana kakumei)” [The fifth part: Bringing up children (2) groups of learning infants – the unforeseeable future (Women’s quiet revolution)], Nihon Keizai Shimbun (chōkan) (May 21, 1998): 1.

21 “Chiteki ni ajitsuke, majime o tanoshimu – kyōiku suru omocha, papa ga muchū ni” [Intellectual entertainment: enjoying seriousness - Fathers become absorbed in educational toys], Nikkei Ryūtsū Shimbun (June 4, 1991): 24.

22 “Chiiku omocha hattatsu, ‘sōzōsei nobite’ wagako ni kitai – kōreisha mukeni rihabiri yō mo” [The development of toys for intellectual training. Parents expect much in the future of their children, as their ‘creativity develop.’ - There are also toys for the rehabilitation of elderly people], Nihon Keizai Shimbun (yūkan) (October 21, 1999): 18.

23 In fact, the company also faces various managerial problems. For example, in the coronavirus pandemic situation, KID-O-KID with its large fixed costs is now required to transform its profit structure. In addition, there is a possibility that the company’s strategy to set “Europe as the goal” will backfire, if the political turmoil in Europe continues.

24 See also Sakai (2019).