2023 Volume 7 Issue 2 Pages 31-40

2023 Volume 7 Issue 2 Pages 31-40

Numerous children with undernutrition exist in Timor-Leste, and there is an urgent need to improve this situation. Insufficient dietary diversity affects the nutritional status of children. Therefore, we developed and conducted a nutrition education program for guardians of children in Dili, Timor-Leste. The nutrition education program took place over five consecutive days. In order to establish understanding of children’s nutritional status and the need for a well-balanced and varied diet, six goals were established so that participants can be practiced at home. We report results about this program from July 2019 to March 2021. We verbally explained to participants data would be anonymized, and all participants verbally provided informed consent to participate in the program, the study, and its publication.

Forty-five nutrition education programs were conducted during the data collection period, with 218 parents or guardians and 311 children. Each guardian participated in one series over a span of five days. The food intake of the participants’ children was biased toward carbohydrates and lacked diversity. The menus devised by the participants on the last day of the program showed a decreased tendency to cook with only one food group and an increased in the percentage of cooking with all three food groups. Positive impressions about the program were received from participants. This program provided participants with lunch, snacks, and transport service, which may motivate participation.

To develop intrinsic motivation among guardians, it is necessary, above all, to create an environment that is conducive to participation, which in turn will lead to the realization of the need for healthy meals. This nutrition education program could be an effective to increase guardian's understanding about importance of diet diversity.

Malnutrition is the deficiency, excess, or imbalance in the intake of energy or nutrients. Malnutrition includes undernutrition, which results in low body weight, manifesting as stunting (low height-for-age), wasting (low weight-for-height), and being underweight (low weight-for-age) (World Health Organization, 2020). Undernutrition remains a major problem in low- and middle-income countries, and this condition can increase the mortality rates associated with diarrhea, measles, pneumonia, and malaria; it appears in 45% of children under 5 years of age. During pregnancy, undernutrition of the mother has adverse effects on fetal growth. Undernutrition in the first 2 years of life is a major determinant of stunted growth, subsequent obesity, and noncommunicable diseases in adulthood (Black et al., 2013). Women who were stunted in early childhood are more likely to suffer stunting as adults (World Food Program, 2019). In addition, undernutrition in childhood may decrease later academic performance and economic status (Victora et al., 2008). Therefore, undernutrition limits a child’s future potential and affects the next generation.

The Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste’s collaboration with national and international organizations precedes its gaining of independence in 2002, and with their help, has established a health service for its citizens. As a result, the mortality rate of infants and children under 5 years of age has significantly decreased, and Timor-Leste ranks among the countries found to have the most improved health-related Sustainable Development Goal indicators (GBD 2015 SDG Collaborators, 2016). However, a national nutrition survey of children under 5 years of age in Timor-Leste found rates of stunting, wasting, and being underweight of 50.2%, 11%, and 37.7%, respectively (Ministry of Health, 2015). In almost 50% of Timor-Leste’s children, nutritional status is impaired.

The basic causes contributing to undernutrition include household poverty, socio-cultural factors and political context. Additionally, inadequate household sanitation, lack of dietary diversity, food insecurity, and inadequate access to health services are associated with undernutrition (Provo et al., 2017). However, among children aged 24–59 months, 50.6% have adequate meal frequency (≥3 meals and ≥1 snack), and 40.6% have adequate dietary diversity (≥4 food groups). Overall, only 25.1% of children in Timor-Leste meet the criteria for adequate meal frequency and diversity (Ministry of Health, 2015). Dietary diversity is a major element of a healthy diet and is significantly associated with child growth (Ruel, 2003). However, the diet in Timor-Leste is heavily starch-based because few foods of vegetable and animal origins are available (World Food Program, 2019). Such plant-based diets tend to be low in micronutrients, and those micronutrients present are often in a nonabsorbable form (Ruel, 2003). Loss of dietary diversity leads to poor nutritional status.

A survey of adolescent girls ages 14-19 years in Timor-Leste found a significant relationship between nutritional knowledge and their body mass index (BMI), with a similar association found between their mother's education level and adolescent girls' BMI. As a poor understanding of nutrition appears to contribute to undernutrition, schools should provide nutrition education (Soares & Yamarat, 2014).

It is also necessary to provide guardians such as parents, grandparents, and siblings, with sufficient knowledge of the nutrition needed by their children. The government of Timor-Leste now provides nutrition education as a public health service and encourages guardians who come to public health facilities; the Community Health Center and Health Post to measure their children’s growth. This government-funded educational service focuses on the need to consume various types of foods to improve nutrition and health. However, because of the broad focus on the target population, there is no way to evaluate whether each guardian understands the content.

Our nonprofit organization in Japan provides ophthalmology support to Timor-Leste and collaborates with a local nongovernmental organization (NGO) to improve the nutrition of children in the region. In this context, we, along with NGO staff, including a nurse and a nutritionist with research and work experience in Timor-Leste, developed a nutrition education program for guardians who care for children and completed an initial plan for this in February 2019. In March 2019, the nurse and nutritionist visited Timor-Leste, and sought and received advice from the medical staff of a community health center in Dili and the Ministry of Health in Timor-Leste. Based on this input, we revised and finalized the program along with the local NGO staff. We launched the nutrition education program in July 2019. The program is still conducted. This report describes developing and implementing a nutrition education program in Dili, Timor-Leste.

Our nutrition education program aims to provide participants with an understanding of what constitutes a healthy diet for a child. One series is five days from Monday to Friday. Based on developing an understanding of children's nutritional status and the need for a well-balanced and varied diet, the following goals were established so that participants can be practiced at home. Within this remit, we set six goals as the learning outcomes for participants, as described below:

Goal 1: Understanding their child’s growth using body measurements

Goal 2: Understanding the functions of the three food groups: body-building, energy, and protective foods

Goal 3: Classifying foods into each category

Goal 4: Understanding the amount of the three food groups needed per meal

Goal5: Learning to cook healthy meals

Goal 6: Understanding the necessity of hygiene, such as handwashing, when preparing food

2. The nutrition education program staffThe nutrition education program staff comprised a team of five from a local NGO, including two instructors, a cook, a cleaner, and a driver. In addition, volunteer medical students took care of the children during the program. Before program initiation, the instructors learned about nutrition and child body measurements at a local community health center.

3. Workshop Schedule and ContentsThe nutrition education program was a workshop that reflected the six educational goals (Table 1). Goal 1 for participants was learning to measure their child’s weight, height, and arm circumference and to find these measurements on the growth curve in their Livriñu Saúde Inan no Oan (mother and child health booklet) that was provided to pregnant ladies by the Ministry of Health in Timor-Leste to confirm their child’s growth. Goal 2 was to learn about the three food groups and well-balanced food intake. This information was consolidated using a story to illustrate the detrimental effects of an unbalanced diet on health. To understand goal 3, participants were shown photo cards of foods and asked to classify each into one of the three food groups. They were also asked to describe the function of the three food groups. For goal 4, the amount of each food group necessary in a single meal was explained, with portion sizes measured using a child’s hands. Photographs of meals were shown, including balanced meals, meals with excessive amount of a food group, and meals with food group deficiencies. To achieve goal 5, a cooking demonstration was given, showing participants how to prepare a healthy lunch and snack. At that time, we explained the ingredients and cooking methods and the reasons and methods for washing the ingredients and utensils before use. For goal 6, we read a story about the necessity of handwashing and demonstrated washing the hands with soap.

After each workshop, the instructors checked the participant’s comprehension of each of the six goals. For example, for goal 4, they interacted with participants to ask about balanced food intake and to suggest improvements, such as, “adding another vegetable” or “putting eggs in porridge for one meal every three days.”

Each day, we provided snacks at 10 am and lunch at 12 pm and had participants wash their hands with soap before eating their meals. We explained how to cook healthy and nutritious meals and sang songs on the themes of handwashing and nutrition. On the last day of the workshop, participants made their breakfast, lunch, and dinner menus as confirmation of their learning in the program. Each gave a presentation of their menu in which they described the ingredients and cooking methods. Participants who attended the workshop for the full five days received a nutrition education program certificate, and their children received a stamp card.

This program was run from 9 am to 1 pm, Monday through Friday. The maximum number of participants accepted was 10, and participants could bring their preschool children to the program. Due to the lack of transportation in Dili, we provided a transportation service (by car) to and from the program. In addition, lunch and snacks were provided so that meals using the three food groups could be seen and experienced.

The educational material used in this program was mainly pre-existing materials. These included flipcharts created by the Ministry of Health as visual aids to explain handwashing and the three food groups. We purchased photo cards of ingredients and songs about nutrition and hygiene from local healthcare support groups. In addition, we asked a Japanese university volunteer group to create kamishibai–storytelling with pictures to illustrate the necessity of nutritional balance and handwashing. These were presented to participants by local medical students. The lunch recipes were created by the Ministry of Health or selected from Resita’s Hahan Saudavel Ba Bebe, Labarik, Inan no Familia (Healthy Food Recipes for Baby, Child, Mother, and Family). All ingredients used were available in Timor-Leste.

5. Participant Recruitment and Data CollectionThe target population of the nutrition education program was guardians of children and anyone who wished to participate. To recruit participants, we explained the program schedule and content and that snacks, lunch, and transportation by car would be provided. With the cooperation of the community health center, participants with children whose physical measurement scores were lower than the standard values were informed about the nutrition education program and invited to participate. The program instructor then contacted the participants, obtained their consent to participate, and arranged for them to attend a workshop. We also visited local neighborhoods to inform residents about the program and recruit participants. We explained to participants orally that the data collected would be anonymized and all participants provided verbal informed consent to participate in the program and the study and its publication.

The data collection period was from July 2019 to March 2021. Participant data collected were the age of the participants, number of children under their care, their educational background, their previous nutrition education, and the number of people living in their household using interview in the Tetun language. Food intake by children the day before the first day of the program and food from the menu formats devised by participants on the last day of each series of the program were collected and classified into three food groups. The age, height, and weight of children were also collected and evaluated using the WHO child growth standard. We also collected data on the impressions of program participants to whom staff called out to and feedback from the instructors and other staff using informal interview. The program was designed as a workshop to be held over five consecutive days; however, participants who did not complete the program were included in our data analyses. The participants’ character and children’s physical measurements were collected on the first day of the program, whereas the menus they devised were collected on the last day of the program.

Forty-five nutrition education programs were conducted during the data collection period, with 218 participants (Table 2) and 311 children whom participants brought.

Each guardian participated in one series over a span of five days. In the tables, the total number of responses to different questions varies due to incomplete questionnaires or participants not knowing the answers to specific questions. Most participants (66.4%) were aged 20–30. Most (59.6%) cared for 1–2 children, followed by 3–4 children (22.5%). Only 6.9% of participants had received previous nutrition education, and almost all were uneducated about nutrition. The numbers of household members were as follows: 35.5% had 1–5-person households, 47.5% had 6–10, 14.5% had 11–15, and 2.5% had 16–20-person households. The educational background of the program participants was middle school (14.1%), high school (54.4%), and university (17.5%) (Table 3).

There were 244 children who could be measured height and weight: 55.3% of them were stunting (height-for-age ≤ −2 z score), 46.6% of them were wasting (weight-for-height ≤ −2 z score), and 61.5% of them were underweight (weight-for-age ≤ −2 z score).

As for the children’s meals, the day before the program, at breakfast, 53.1% of participants consumed food from foods with high energy contents. At lunch, 43.4% of participants consumed food from two food groups. At dinner, 40.2% of participants consumed food from two food groups. Some participants missed meals, with 5.8% missing lunch and 6.1% missing dinner. The number of children who consumed food from all food groups was comparatively low (Table 4).

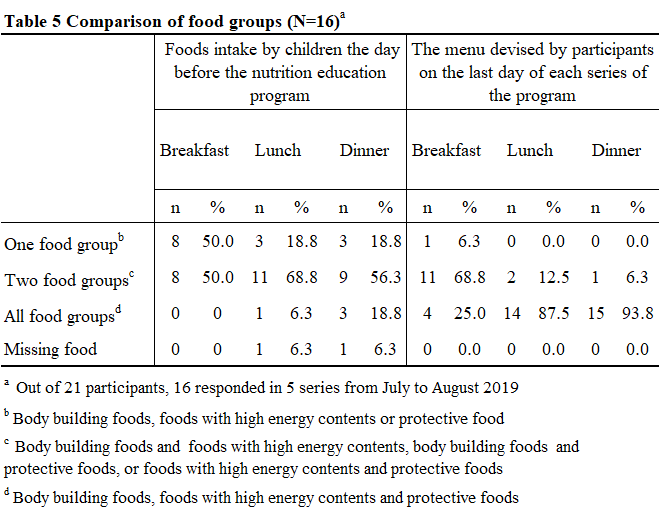

Out of the 21 participants who took part in five series from July to August of 2019, only 16 could retrieve the data; comparison of the food consumed by children the day before the program and the menus devised by participants on the last day of each series of the program showed that only 6.3% of the dishes were prepared using food from one group at breakfast. The percentage of menus devised using ingredients from all groups was 25% for breakfast, 87.5% for lunch, and 93.8% for dinner (Table 5).

Feedback from the program participants and staff was collected. A sample of participants’ impressions were as follows: “It was fun,” “I want to come again next week,” “It was fun to talk to other participants because I don’t have anything to do at home,” “I don’t use chemical seasonings,” and “The transportation service was good because I have a baby.” They also commented, “It made me and my child happy to eat healthy meals during this program” and “I’m glad I could learn how to cook healthy meals.” Some participants reported making the banana-steamed bread that they learned to make in the cooking demonstration at home and showing it to relatives and neighbors. Some transcribed the lyrics of the handwashing and nutrition songs to sing with their children. Feedback from staff was “This program is very meaningful. Many participants did not know what a healthy diet was or what nutrients are but now they understood the need for a healthy diet for their children.”

Despite learning the necessity of the three food groups, some participants, in reality, cannot afford these foods. In addition, some participants said that the fish dish “is delicious but cannot be made at home” because it had a complicated cooking process. Some participants took home leftover lunches and snacks.

Although the global COVID-19 pandemic disrupted this program, there were 218 adult participants, including those who did not complete the full program. Participants generally enjoyed learning. A systematic review of the determinants of participation in workplace health promotion programs found that program participation was higher when incentives were offered (Robroek et al. 2009). Our nutrition education program provided participants with lunch, snacks, and transport to and from the program facility for the five days of attendance. Positive impressions were received from the participants regarding these offerings, which may be a motivating factor for participation. It is expected that actions initiated by extrinsic motivation will eventually shift to intrinsic motivation by providing feedback to participants on the effects of such actions. To develop intrinsic motivation among participants, it is necessary, above all, to create an environment that is conducive to participation, which in turn will lead to the realization of the need for healthy meals.

2. Learning Outcomes of the Nutrition Education ProgramThis nutrition education program aimed to help participants understand healthy food intake to improve children’s nutrition. Six learning goals were established to achieve this, and a workshop program was implemented. The food intake of the participants’ children was biased toward carbohydrates and lacked diversity. However, the menus devised by the participants on the last day of the program showed, a decrease in cooking with one food group and an increase in the percentage of cooking with all three food groups.

Nutrition education programs in low- and middle-income countries have been noted to effectively improve the nutrition knowledge of guardians and the diversity of their children’s diets (Effendy et al., 2019; Kajjura et al., 2019; Reinbott et al., 2016; Waswa et al., 2015). Similar effects were observed in this program, which may have increased their knowledge about the importance of diet diversity. Understanding the necessity of dietary diversity and practicing it at home are the first step to improving the nutritional status of the children of Timor-Leste. Raghupathi, V and Raghupath, W (2020) reported that education allows individuals to acquire skills/abilities, and knowledge on general health and enhance their awareness of healthy behaviors and preventive care.

Incidentally, most guardians who participated in the program also had a higher level of education. In a health survey in Timor-Leste, mothers with higher education were more likely to use medical care than those with lower education (General Directorate of Statistics, 2018). These highly educated guardians seemed to be interested in their children’s health and may have accessed a community health center or responded to our invitation to participate. Studies examining the relationship between maternal education and children’s nutritional status concluded that the mother’s level of education affects the child’s nutritional status and that the level of education can be a factor in child undernutrition (Abuya et al., 2012; Stamenkovic et al., 2016). This indicates that maternal education is important to improve the nutritional status of children in Timor-Leste as a whole. Commitment to the program is necessary; therefore, considering those who did not participate in this program is important. Although further consideration is needed, one approach would be to visit guardians who do not or cannot access medical facilities and encourage their participation.

This report has limitations. Because participants proffered to take home their own menu forms, we were only able to collect a portion of data. It is necessary for participants to cook the menus created in this program at home to continue to produce good meals. In contrast, the data are also necessary; therefore, it will be necessary to collect the data in the future by making copies of forms or recording them. Further research is needed to evaluate each aspect of this nutrition education program to verify and improve its effectiveness.

We received generous support from Kyoko Sakanishi and NAROMAN, Handmaids of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, and Rafaela East Timor Fund. We also acknowledge COMORO Community Health Center, Student volunteer group “Saru to Wani” at Seisen University, Yui Fukahori, Juvencio Soares, and Hitomi Shibuya.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

AW and KN collected program data. RM analyzed the data. AW produced the first draft and NT and RM reviewed the draft. All authors edited and approved the final version.