2023 Volume 11 Issue 3 Pages 46-54

2023 Volume 11 Issue 3 Pages 46-54

The shoulder width (width of the parascapular cross-section) is the greatest among various body widths and thus, it may complicate the passage of the fetus through the pelvis. The shoulder width is at its greatest when the arms are elevated in the breech presentation. It is important to understand three principles to deform or reduce the shoulder width, deliver a trapped shoulder, or align the shoulder axis with the wider diameter of the pelvis.: (1) elevation or descent of the unilateral shoulder joint (avoiding simultaneous entry of both shoulders into the pelvis); (2) internal rotation of the shoulder joint (reduction of the shoulder width and contact of the forearm with the chest wall); and (3) matching the shoulder axis to the pelvic oblique diameter or transverse diameter.

In cases of shoulder dystocia, (1) the anterior shoulder is first guided into the pelvis to prevent the simultaneous entry of both shoulders (suprapubic pressure), however, advancement of the posterior (opposite) shoulder, is also possible (Schwartz method). (2) Pushing the shoulder forward (internal rotation of the shoulder joint: [Rubin method, Woods corkscrew method]) reduces the shoulder width. Internal rotation of the shoulder is induced by a forward-pushing maneuver from the fetal back. (3) As the oblique and transverse diameters are greater than the anteroposterior diameter in the plane of the pelvic inlet, the fetus should be guided for the shoulder axis to match the oblique or transverse diameter, rather than the anteroposterior diameter (Woods corkscrew method, reverse corkscrew method).

The classical method of freeing the shoulders and arms in the breech presentation is performed as follows: (2) the posterior shoulder is first pushed forward and downward from the fetal back (internal rotation of the shoulder joint), with the fetal forearm closely contacting the chest wall. Then, (1) the shoulder is extracted downward by pulling the elbow joint of the posterior shoulder to deliver the arm. (3) The shoulder axis should match the oblique diameter. Freeing the arm leads to the advancement of the posterior shoulder, because this maneuver is performed while the fetal trunk is pulled upward. Freeing the shoulder and arm should always be performed from the fetal back with the same-side hand. In cases of arm elevation or a nuchal arm, internal rotation of the shoulder joint is particularly important. The upper arm and forearm should be made to descend in such a manner that they contact the face and head.

Various maternal and neonatal complications, such as placenta accrete spectrum, uterine rupture and transient neonatal tachypnea, have increased the incident of cesarean sections, which has prompted us to review their implementation. Recent studies have demonstrated that positive outcomes from vaginal breech delivery are possible when appropriate cases are selected.1,2,3,4,5) Therefore, vaginal delivery is increasingly performed for multiparous women with fetal breech presentation and cases of vaginal delivery of the second twin in breech presentation. Thus, breech extraction skills should be included in the education of midwives, physicians, and obstetricians.

Learning the necessary obstetric skills for breech extraction and shoulder dystocia is difficult. Students, younger midwives, and physicians often experience difficulties regarding stereotactic viewing, even if they use quality textbooks with detailed illustrations and graphics.6,7) Additionally, on-the-job training for such skills is typically not available in actual obstetric practices due to the paucity of patients requiring such techniques. Previously, younger physicians and obstetricians could directly learn obstetric skills and knowledge not found in textbooks from senior obstetricians, which included successes and failures in breech extraction, tips and the techniques, and the management of shoulder dystocia. However, physicians and obstetricians nowadays also deal with their daily practice, and the number of patients requiring such a skill set is small, resulting in many physicians feeling as if they have insufficient experience or improficiency.

Simulation training using models has been introduced in Japan to educate students and practitioners in emergency medicine.8) Additionally, easy-to-learn materials using computer-generated animations for theory and practice, —including the subsequent steps if things do not go as planned, —are available and helpful in clinical practice.9,10) Herein, we explain the theoretical and practical skills, such as extraction of the shoulder and arms, required for breech extraction and management of shoulder dystocia.

The shoulder joint is composed of three bones (humerus, scapula, and clavicle) and various soft tissues, including ligaments, muscles, and the synovial bursa. These tissues allow the shoulder to move in various directions. When attempting the delivery of the arms and shoulders, it is necessary to be familiar with and understand their movements based on their ranges of motion and directions of movement to reduce the shoulder axis for an easier delivery. Although the shoulder width is broader than the biparietal diameter of the fetal head, the shoulders can be delivered by reducing the shoulder width through various movements, deformations, and location shifts. The range of motion of the upper limb is limited posteriorly, while maneuvers at the front of the body are easier to perform. As the movement of the upper limb is restricted within the narrow uterine cavity, movement along the trunk is easier and safer.

The shoulder joint can move in eight directions: abduction and adduction in the coronal plane; flexion and extension in the sagittal plane; horizontal extension (horizontal abduction) and horizontal flexion (horizontal adduction), with arms extended horizontally; and external rotation and internal rotation of the forearm, with the upper arm in close contact with the trunk in the axial plane.

Horizontal flexion and internal rotation of the shoulder joint are effective for reducing the shoulder width, resulting in a position similar to the “shrinking posture”, as seen in cold weather (Figures 1). Although horizontal flexion of the extended arm is difficult in the narrow uterine cavity, it is important to push the shoulder joint forward from the fetal back, which causes anterior transposition of the shoulder joint, reduction of the shoulder-width diameter, and contact of the forearm with the anterior surface of the trunk, freeing the upper limb. Therefore, freeing and delivering the shoulder in cases of shoulder dystocia or breech presentation should be facilitated using a posterior approach from the fetal back and by pushing forward the shoulder joint.

Movement of the shoulder joint for reducing the shoulder width.

When the “swaggering posture” (A), in which the chest is expanded, is compared with the “shrinking posture” (B), as seen in cold weather, the shoulder width is shorter in the latter posture, i.e., the shoulders are internally rotated and slightly elevated. Internal rotation of the shoulder joint involves anterior extrusion of the shoulder, and the upper limb, particularly the forearm, is in contact with the anterior chest wall. The technique to reduce the shoulder width is extremely important to manage shoulder dystocia and free the arm in breech presentation without causing injuries to the fetus.

When performing the Rubin maneuver,11) it is important to push the shoulder anteriorly, with respect to the fetus, from the fetal back (Figure 2). When freeing the shoulder and arm in cases of breech presentation, the operator should use the same-side hand as that of the fetus and approach from the fetal back.9) During this time, the operator should push the shoulder joint from the fetal back to cause horizontal flexion and internal rotation of the shoulder and position the upper limb of the fetus on the anterior surface of the trunk; these movements facilitate the freeing maneuver (Figure 3).

The Rubin maneuvers for shoulder dystocia (A) in frontal view and (B) in lateral view.

The anterior shoulder of the fetus should be excluded in the fetal ventral direction while rotating it internally to allow delivery of the shoulder. During oblique deviation of the pelvic anteroposterior diameter and the axis of the fetal shoulder, the fetal shoulder should be guided to the front and in the maternal dorsal direction to facilitate passage through the posterior surface of the pubis.

Delivery of the shoulder and the arm in classical breech extraction (A) in the frontal view and (B) in the lateral view.

The classical method of freeing the shoulders and arms is performed by elevating both feet of the fetus, thus making as broad a space as possible between the fetus and the posterior region of the pelvis. The operator inserts the same-side hand as the fetal arm from the fetal back until it touches the shoulder. The hand should push the shoulder from the fetal back (A) and advance from the shoulder to the arm. The forearm flexural area of the elbow joint should be in contact with the index finger or with the index and middle fingers (B). Using these fingers, the fetal arm is gently freed along the anterior surface of the fetal thoracoabdominal region. During this step, pushing the shoulder joint forward to cause internal rotation will make the flexural area of the elbow joint contact the anterior surface of the trunk, facilitating the freeing procedure.

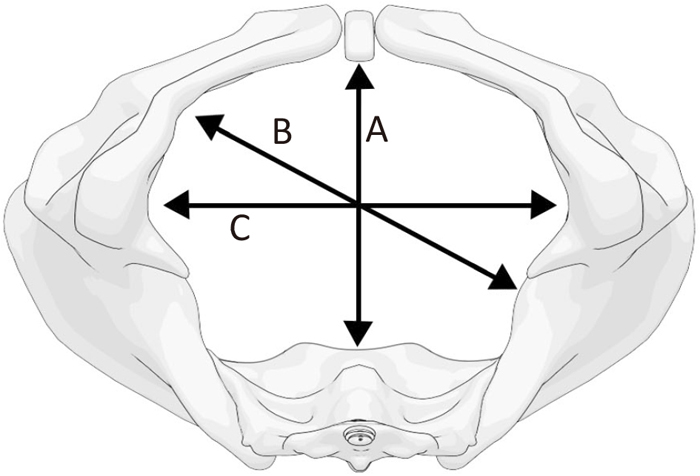

The progression of delivery is determined by three elements: the birth canal, the fetus and expulsive force; an abnormal delivery is characterized by abnormalities in these elements. In the plane of the pelvic inlet, the true obstetrical conjugate, which is the shortest distance between the sacral promontory and the symphysis pubis, is an important factor that affects the progression of delivery in terms of the relationship between the fetus and the bony birth canal (Figure 4). The true obstetrical conjugate is used to diagnose cephalopelvic disproportion. Meanwhile, the broadest transverse diameter in the fetal body is the shoulder width (the major axis in the parascapular cross-section) (Figure 1). This parascapular cross-section can be deformed and reduced because of the wide range of motion of the scapula, which does not cause any problems in cases of normal delivery. However, in cases of shoulder dystocia or breech extraction, it is difficult for the fetus to pass through the pelvis within the range of normal change and deformation of the shoulder width. When managing such cases, it is important for the operator to not only be familiar with the method of delivery of the shoulders or the arms but to also have adequate knowledge regarding the anatomical features of the pelvis and the range and direction of motion of the shoulder joint. A good understanding of these factors will enable the successful management of shoulder dystocia and the implementation of breech extraction by freeing the arms, leading to the safe delivery of the fetus. With the proper knowledge, the operator can perform a second procedure, even if the first procedure fails to deliver the fetus.

Inferior view of the female pelvis: (A) the anteroposterior diameter, (B) the oblique diameter, and (C) the transverse diameter.

The pelvic internal diameter varies according to location. At the inlet, the anteroposterior diameter is usually shorter than the oblique or transverse diameter. At the time of passage of the shoulders through the inlet plane, the fetus can more readily enter the pelvis if the shoulder axis of the fetus matches the oblique or transverse diameter rather than the anteroposterior diameter. Therefore, if the shoulders of the fetus become stuck while passing through a narrow area, it is important to move the fetus in a manner to make the shoulder axis match a broader diameter, such as the oblique or transverse diameter of the pelvis.

In cases of shoulder dystocia, it is important to move the anterior shoulder joint to deform it, resulting in the reduction of the major axis of the shoulder width. In cases of normal delivery with the fetus in the occipitoanterior position, the fetal head should be pulled downward to deliver the anterior shoulder first when the shoulder needs to be delivered after the delivery of the fetal head. Using this method of delivery of the shoulder, the anterior shoulder is elevated against the body axis in the parascapular cross-section, thereby reducing the major axis and facilitating the passage of the shoulder under the pubis and its entrance into and passage through the pelvis (Figure 5). In cases of shoulder dystocia, such downward traction will not lead to the delivery of the fetus. Therefore, it is important to reduce the major axis in the parascapular cross-section to a greater extent in comparison with the pelvis in such cases. The first procedure involves further advancement of the anterior shoulder and elevation of the shoulder into the pelvis. The application of suprapubic pressure will facilitate the advancement of the shoulder and its elevation. When the anterior shoulder is advancing in cases of shoulder dystocia, if not delivered successfully by suprapubic pressure in the McRoberts position, we should next perform the Rubin maneuver (Figure 2).7,9) However, if the posterior shoulder is advancing, we should perform the Schwartz maneuver to deliver the posterior shoulder and the arm first (Figure 6).7,9)

Raising the shoulder in normal delivery.

In cases of normal delivery, delivery of the anterior shoulder should be assisted after the fetal head is delivered from the perineum. When the head is pulled downward in the fourth rotation, the anterior shoulder moves forward (the anterior shoulder is elevated and precedes the posterior shoulder in the lateral view) and passes under the posterior surface of the pubis, resulting in delivery. Because the two shoulders cannot enter the pelvis simultaneously (A), the passage of the anterior shoulder should be ensured first (B). If the fetus is pulled downward (delivery of the anterior shoulder) and then upward (delivery of the posterior shoulder), similar to pulling a cork out of a wine bottle, the shoulders can be delivered.

The Schwartz maneuvers for raising and delivering the posterior shoulder and arm.

The Schwartz maneuver is a technique to raise and deliver the posterior shoulder. Whereas the Rubin maneuver aims to internally rotate the shoulder joint and match the shoulder axis with the oblique diameter, the Schwartz maneuver aims to directly deliver the posterior shoulder. The anterior shoulder is stuck in a narrow space since the pubis is on the ventral side. In contrast, the posterior shoulder has a relatively larger space to move in than the anterior shoulder because only the coccygeal bone is in the bony birth canal on the dorsal side of the posterior shoulder. Therefore, when the Rubin maneuver is not effective, it is reasonable to attempt delivery of the shoulder to raise the posterior shoulder joint and arm.

During breech extraction, it is important to simultaneously lower the posterior shoulder joint and internally rotate the shoulder to reduce the major axis of the shoulder width, resulting in the delivery of the posterior arm and shoulder (Figure 3b).

2) Internal rotation of the shoulder jointPushing the shoulder forward from the back causes the shoulder joint to rotate internally, leading to further reduction of the shoulder width and resulting in a position similar to the “shrinking posture” (Figure 1). This rotation of the shoulder joint aids the progression through the pelvic canal by reducing the shoulder axis width (Figure 7). Usually, internally rotating, raising, and advancing the shoulder are performed simultaneously to reduce the shoulder width; this concept is used in the Rubin maneuver (Figure 2) and the Woods corkscrew maneuver for shoulder dystocia. If the posterior shoulder cannot be reached, the maneuver should involve the anterior shoulder alone.

Internal rotation of the shoulder joint.

(A) axial view, the shoulder axis width; (B) axial view, reduction of the shoulder axis width by internal rotation of the shoulder joint; (C) anterior view, internal rotation of the shoulder joint; and (D) anterior view, an arm elevated or transpositioned to the back of the neck (nuchal arm) in breech presentation. A nuchal arm results in the greatest shoulder width, making delivery of shoulders and arms extremely difficult.

Internal rotation of the shoulder joint consists of making the forearm face inward while maintaining the upper arm in contact with the trunk. With this technique, the shoulder joint moves forward, and the shoulder axis is reduced. This is a position similar to that of a person who is huddled and shivering, with the forearms in contact with the trunk (shrinking posture) (Figure 1B).

Conversely, the shoulder axis becomes longer when a person expands the chest, opens the upper arms, sets them apart from the trunk, or elevates the upper arms (swaggering posture) (Figure 1A). The shoulder width of the fetus reaches its peak when both upper arms are elevated, making spontaneous delivery extremely difficult.

The technique to reduce the shoulder width is extremely important to manage shoulder dystocia and free the arm in breech presentation without causing injuries to the fetus. In cases of shoulder dystocia, rotation of the shoulder joint facilitates a fetal posture ideal for passing the shoulder under the pubis. Additionally, when freeing the arm, the upper limb of the fetus comes into contact with the anterior chest wall, facilitating the safe implementation of the maneuver.

In classical breech extraction, the same concept is used to free the posterior arm and shoulder, causing the forearm to move so that it is in contact with the trunk, which makes freeing the arms easier. Internally rotating and lowering the posterior shoulder also makes the shoulder width narrow, facilitating easier passage through the birth canal (Figure 3a).

3) Guidance of the shoulder axis to allow more space in the pelvic cavityThe third procedure involves rotating and guiding the shoulder axis to match the oblique or transverse diameter rather than the anteroposterior diameter of the pelvic inlet (Figure 8). The oblique and transverse diameters are longer than the anteroposterior diameter; therefore, if the shoulder axis of the fetus is rotated to match the oblique or transverse diameter, the shoulders can be engaged in the pelvis, and thus, the intrapelvic maneuver becomes easier to perform. It is important to push the shoulder joint forward from the fetal back and not just push downward when suprapubic pressure is applied to the shoulder in cases of shoulder dystocia. The maneuvers for this procedure include the Rubin, the Woods corkscrew, and reverse corkscrew maneuvers (Figure 2 and 9).7,9)

Rotation and guidance of the shoulder axis.

The pelvic internal diameter varies according to location. At the inlet, the anteroposterior diameter is shorter than the oblique or transverse diameter. At the time of the passage of the shoulders through the inlet plane, the fetus can more readily enter the pelvis if the shoulder axis matches the oblique or transverse diameter rather than the anteroposterior diameter.

The plane of the pelvic inlet varies in shape among individuals and includes the female type, male type, anthropoid type, and flat type. Therefore, if the shoulders of the fetus are stuck while passing through a narrow area, it is important to move the fetus to make the shoulder axis match a broader diameter.

Regardless of whether the presentation of the fetus is cephalic or breech, it is difficult for the fetus to enter the pelvis when the shoulder axis matches the anteroposterior diameter of the pelvis (A). Therefore, it is important to rotate the shoulder axis to match the oblique diameter or transverse diameter, both of which are broader than the anteroposterior diameter (B), and to use maneuvers to guide the fetus to facilitate passage through the pelvis in cases of shoulder dystocia as well as breech extraction.

The Woods corkscrew (A) and the reverse corkscrew maneuver (B).

The Woods corkscrew maneuver aims to rotate the anterior shoulder in the fetal ventral direction and the posterior shoulder in the dorsal direction (A). In cases where the Rubin maneuver fails to deliver the shoulders of the fetus, one reason is that the rotation of the shoulders is insufficient, even if there is internal rotation. Backward rotation of the posterior shoulder by this maneuver will cause a deviation between the pelvic longitudinal axis and the long axis of the fetal shoulders, facilitating the delivery of the shoulders.

Woods corkscrew maneuver fails to deliver the shoulders, the reverse corkscrew maneuver (B), which causes rotation in the opposite direction, is used. In many cases, the Woods corkscrew maneuver, as well as this technique, are used serially unless the shoulders are delivered. Both shoulders were delivered when the shoulder axis was matched with the transverse diameter. This indicates that continuing to rotate the shoulder axis according to the shape of the maternal pelvis to match the transverse diameter may lead to delivery of the shoulders when delivery by matching the shoulder axis to the oblique diameter fails.

When freeing the shoulder and arm during classical breech extraction, the delivered lower limbs and the trunk are pulled upward, and freeing the posterior arm is attempted while internally rotating the shoulder joint from the fetal back with the same-side hand to match the shoulder axis with the oblique diameter. A space is created in the sacral frontal area inferior to the fetus, making it easier to free the shoulder and arm. The posterior shoulder is then advanced and lowered by extracting the arm (Figure 3).

In cases of shoulder dystocia, it is important to understand the following procedures and perform the maneuver bearing these procedures: (1) raising and advancing the shoulder, (2) internally rotating the shoulder joint, and (3) rotating and guiding the shoulder axis. In cases of shoulder dystocia, suprapubic pressure on the shoulder should be applied from the fetal back to match the shoulder axis with the pelvic oblique diameter to facilitate passage under the subpubic surface (advancement and internal rotation of the anterior shoulder). Pressure should not be applied directly underneath the shoulder. When performing the Rubin maneuver, the anterior shoulder should be advanced and rotated to match the shoulder axis with the oblique diameter, and the posterior shoulder should be pushed upward and rotated to match the oblique diameter.

The Schwartz maneuver is a technique to deliver the posterior shoulder by directly holding it (Figure 6). When the anterior shoulder is stuck and the Rubin maneuver fails, the trunk is rotated to match the shoulder axis with the oblique or transverse diameter, and the posterior shoulder is advanced and raised by traction of the posterior arm. In the Woods corkscrew or the reverse corkscrew maneuver, the trunk is rotated supinely or pronely to match the shoulder axis with the transverse diameter (Figure 9).

In Japan, the “transverse figure 8 breech extraction” method12,13) is commonly employed to spontaneously free the fetal shoulders and arms, making use of upward and downward pendular movements of the trunk from the Müller maneuver and rotation of the trunk from the Løvset or Maul maneuver.9,12,13) This method of pulling the trunk diagonally, similar to figure 8, during delivery is to guide and pull the shoulder so that it matches the oblique diameter of the pelvis; this is different from classical breech extraction, wherein the trunk is moved up and down like a pendulum. Ultimately, the shoulder width is aligned with the oblique diameter, which is consistent with this concept (Figure 10).

Principles of the transverse Figure 8 breech extraction.

This maneuver pulls the fetus obliquely downward to the right (A) and then to the left to match the shoulder axis with the oblique diameter (B) and advance the anterior shoulder under the pubis. Then, the fetus is pulled upward by pushing the anterior shoulder horizontally from the oblique rear side and pushing the shoulder forward. Thus, internal rotation is induced naturally through traction. More specifically, traction in a Figure 8 pattern allows for the shoulder to move in three directions simultaneously and continuously, facilitating the passage of the shoulders through the pelvis.

If an arm is elevated or transpositioned to the back of the neck (nuchal arm), the arm cannot be freed without performing this maneuver. Thus, it is indispensable to master this technique.1,2,3) A nuchal arm results in the greatest shoulder width, making delivery of the shoulders and arms extremely difficult. In these cases, the shoulder joint is abducted and horizontally extended. Therefore, the shoulder should be horizontally flexed more strongly in contrast to the usual method of freeing the arm by placing the elevated arm on the fetal face. First, if the anterior arm is elevated or is the nuchal arm, the fetus should be rotated to make this arm the posterior arm because the freeing procedure is performed for the posterior arm. Then, the operators should place their fingers on the elbow joint to help the elevated arm descend along the face and trunk. This process of freeing the shoulder and arm consists of the same concepts, such as internally rotating the shoulder joint, lowering the posterior shoulder, and matching the shoulder axis with the oblique diameter to create space in the pelvic cavity. These adequate and reliable maneuvers will successfully free the shoulder and arm.

We would like to thank Honyaku Center Inc. for English language editing.

None.