2024 Volume 12 Issue 1 Pages 16-19

2024 Volume 12 Issue 1 Pages 16-19

The Maternal and Child Health Handbook (MCH Handbook) in Japan contains a wide range of material related to pregnancy and childcare and has been revised every 10 years. At the review meetings on the MCH Handbook in 2022, 5 points were mainly discussed: (1) mental health care for women during pregnancy and postpartum, (2) care for family members other than mothers, (3) appropriate contents considering diversity, (4) methods of recording children’s growth and development, and (5) combined use of the electronic MCH Handbook.

The Maternal and Child Health Handbook (MCH Handbook) supports the integration of maternal, neonatal, and child health services and is currently used in more than 50 countries.1,2) It guarantees continuous and appropriate care for mothers and children worldwide. In 1948, Japan created the world’s first MCH Handbook. In 1966 in Japan, the MCH Handbook underwent a major revision and was legislated under the new Maternal and Child Health Act.

The MCH handbook in Japan contains a wide range of material related to pregnancy and childcare, such as vaccination records, growth charts, and health education information. The MCH Handbook is distributed to all pregnant women who submit a pregnancy notification to local governments in Japan. It has been revised every 10 years to address the evolving key MCH agenda.

In 2022, the MCH Handbook was revised, for which the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare held several review meetings on the MCH Handbook and maternal and child health. I attended the revision committee meetings recommended by Japan Association of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (JAOG). Therefore, I will consider the future image of the MCH Handbook in Japan.

In general, the most important aspect of the MCH Handbook has been that it provides important information on the health of the pregnant woman and fetus, the mother and neonate at delivery, and the infant after birth, all in one handbook managed by the guardians themselves (Figure 1).1,2) The MCH Handbook in Japan consists of a common national format specified by Ministerial Ordinance (from the front cover to page 53; including the pregnancy, health checkups during infancy, immunizations, and physical growth curves of infants), and a unique format in each municipality including information on daily life, childrearing, nutritional intake for pregnant women and infants, and immunizations. The latter also consists of information on systems and services in each municipality. It is also a very useful tool for maternal and child health services to record when such services are received and the vaccination status. In addition, even if the medical institution or municipality where the pregnant woman or infant resides changes, the information can be used as basic data for providing appropriate medical treatment and health care services.

At the review meetings on the MCH Handbook, we mainly discussed the following for the revision, considering future digitalization of the handbook.

1. Mental health care for women during pregnancy and postpartumFirst of all, the importance of perinatal mental health care was discussed.

In Japan, 10–15% of all mothers have reported becoming depressed during pregnancy and postpartum.3,4) If people do not receive adequate support during large life events such as pregnancy and childcare, they sometimes easily become depressed, which could lead to suicide.

For example, there were 63 maternal suicides in Tokyo over the past 10 years.5) By extrapolating the data nationwide, 60 to 70 women commit suicide every year during pregnancy and postpartum in Japan. This number is about 1.5 times the number of maternal deaths due to perinatal complications such as postpartum hemorrhage. In addition, there were reportedly two peaks in the timing of maternal suicide in Tokyo. The first peak occurred in the early stage of pregnancy, which might be associated with anxiety due to unexpected or unwanted pregnancy. The second peak occurred during the 3 to 4 months after delivery, which might correspond to the time when the burden of childcare becomes heavier.

In my earlier study, about 80% of women with postpartum depression may have exhibited depressive symptoms during pregnancy.6) Therefore, postpartum depression may be prevented by continuous care starting from pregnancy (Figure 2).3) By (self-)recording the mental status of pregnant women in the MCH Handbook in real time, perinatal staff and local government agencies may be able to intervene more rapidly (Figure 3).7)

Paternal depression has become a hot topic in recent years in Japan, and it has been a growing belief that the whole family, not just the mother, should be supported.8,9)

In Japan, there had been a strong perception that partners have to support mothers. If a woman developed perinatal depression, even if her partner was doing his best, it would sometimes be misunderstood as indicating ‘his support was not good’. However, the partners’ environment also undergoes major changes similar to those of mothers. Therefore, the partners may also have depression.

The risk factors of paternal depression may be same as those of mothers, paternal depression may also result in bonding disorder, and it has been recognized that the partner’s mental health should also be supported from the pregnancy.8,9,10) Therefore, a space for the recording of partners’ feelings was discussed in revision committee meetings.

3. Appropriate contents considering diversityIn order to provide information to promote support for childcare with consideration for diversity, additions and revisions were made to the contents of the MCH Handbook.1,2)

For example, in Japan, the hurdles seem to be very high for a single parent to take two children outside.11,12) When a mother with twins goes out into a city, she sometimes cannot get on an elevator or bus because the double stroller is too wide. When a mother goes out with twins, she may be sometimes told that ‘she doesn’t have to force herself to come out’ and/or ‘it’s a nuisance’. Many parents of twins go out feeling sorry for those around them. In the childcare of twins, it would be a great help to know the experiences and ideas of those who have experienced it. Therefore, it is necessary to make it easier for them to find places where they can receive support and counseling.

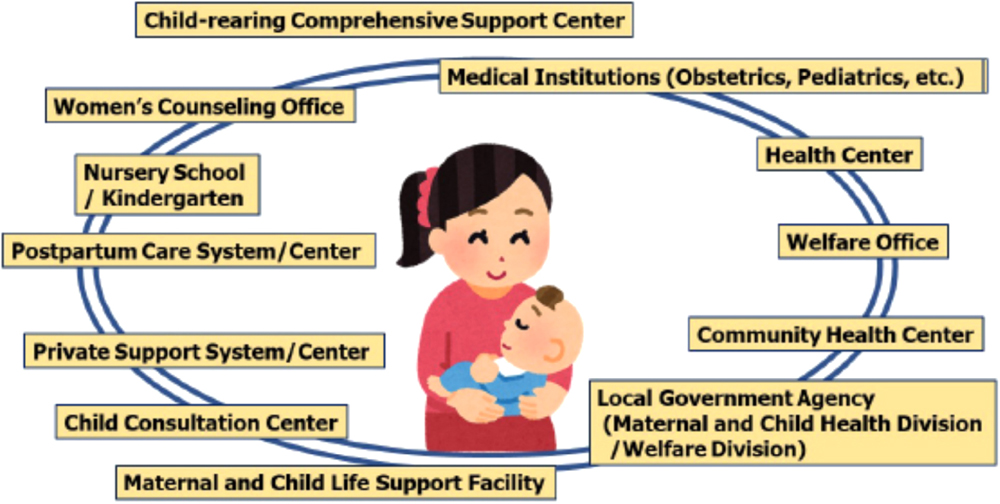

In Japan, there are others experiencing some problems in their lives, such as low birth weight infants, children with congenital abnormalities, and foreign families who cannot speak Japanese. The revised MCH Handbook encourages consultations with some support centers, such as ‘child-rearing generation comprehensive support centers’ and ‘postpartum care systems (services)’, and the usage records of these have been added to the revised MCH Handbook.3,13)

4. Methods of recording children’s growth and developmentIt was discussed that the new MCH Handbook needs to deal with various problems both physically and mentally.1,2) The new MCH Handbook includes some items to deal with various problems considering diversity.

For example, since the MCH Handbook did not contain a growth curve for babies born weighing less than 1,000 g (very low birth weight infants, VLBWIs), there were opinions that mothers and partners who gave birth to the babies felt alienated in the childcare environment.14) Also from the viewpoint of encouraging consideration for the diversity of child growth and development, information on growth curves for VLBWIs will be provided electronically separately from the MCH Handbook, and the Uniform Resource Locators (URLs) for them will be posted in the MCH Handbook.

The new MCH Handbook has been revised considering items and expressions to be able to respond to the needs of various children and their families. In addition, if items cannot be included in the handbook due to space limitations, they will be posted on the website of the Japanese government, and the URL will be posted in the new MCH Handbook.

5. Combined use of the electronic MCH HandbookWe discussed the fact that the MCH Handbook will be used in conjunction with electronic records using smart-phone applications in the future.1,2)

However, in Japan about 1,700 local governments have been working independently to devise digitalization of the MCH Handbook. Therefore, to quickly identify and equally support all mothers and children requiring support in Japan, digitalization requires the unification and standardization of core business systems of local governments. The development of digitalization using the Japanese social number called ‘my number’ will be expected.

In addition, even if it becomes an electronic MCH Handbook, there will be important items for interventions for mothers and their children with various problems.

Here, I considered the future image of the MCH Handbook in Japan based on discussions at revision committee meetings on the handbook.

In Japan, the MCH Handbook will continue to be revised every 10 years, with the aim of making it useful for all children and their families with consideration for diversity, with the awareness that the MCH Handbook will be the property of children.

The abstract of this manuscript was presented at the Workshop of the 22nd Congress of the Federation of Asia and Oceania Perinatal Societies.

I would like to thank Professor Mamoru Tanaka for giving me the opportunity of the presentation, and Drs. Yasuhide Nakamura and Satoru Takeda for their efforts as chairpersons of the workshop at the Congress.

None.