2025 Volume 13 Issue 2 Pages 23-28

2025 Volume 13 Issue 2 Pages 23-28

Vacuum extraction, a procedure used for forced delivery, is effective in assisting vaginal delivery but can cause maternal and fetal complications. Therefore, before the procedure is performed, it should be confirmed that indications and conditions are appropriate for vacuum extraction in accordance with the guidelines for obstetrical practice in Japan. If the procedure cannot be carried out smoothly, alternative delivery procedures should be considered. In addition, if forced delivery by vacuum extraction cannot be completed, forceps delivery or cesarean section must be performed as soon as possible. In particular, when uterine fundal pressure is used in combination with vacuum extraction, findings during the delivery must be documented in detail in the medical record. Finally, neonates born by vacuum extraction should be carefully observed for a certain period of time.

Vacuum extraction (Figure 1) is a procedure used to assist vaginal delivery when labor has stalled. Before the procedure is performed, it must be confirmed that the indications and conditions for vacuum extraction have been met, and if assisted delivery using a vacuum extractor cannot be completed, forceps delivery or cesarean section must be performed as soon as possible.1) In addition, findings during the delivery must be documented in the medical record in detail.

Here we review and outline the practicalities of vacuum extraction versus forceps for forced delivery, and what actions need to be taken if vacuum extraction is not completed smoothly.

Vacuum extraction, like forceps delivery, should be performed as an assisted vaginal delivery method and not otherwise. As with forceps delivery, indications for assisted delivery using a vacuum extractor include (1) non-reassuring fetal status particularly in conditions considered ominous; (2) prolonged second stage of labor (usually 2 hours or more for nulliparous women and 1 hour or more for multiparous women) or arrest of delivery at the second stage of labor; and (3) necessity to shorten the second stage of labor due to maternal complications, such as heart diseases, or/and significant maternal fatigue.1)

The conditions (=status ready for implementation) for vacuum extraction are that the cervix is fully opened, the membranes are ruptured, and the head of the baby is engaged into the pelvic cavity.2,3) These conditions may not be met if the fetus has hemorrhagic or osseous disease, or if the fetus is in the facial or non-vertex position. The vacuum-extracted fetal head must be of a certain size and firmness, and vacuum extraction in preterm labor (especially at <34 weeks’ gestation) or in a fetus with a poorly developed head will increase the risk of intracranial hemorrhage and jaundice in the neonate. In the case of caput succedaneum, the cup usually cannot adhere well to the fetal head, making it easier to slip out without applying sufficient extraction pressure associated with the incidence of repeat dislodgments and also makes it easier to create a cephalhematoma or/and subgaleal hematoma. In macrosomia and highly obese pregnant women, there is a high risk of failure of forced delivery, especially if vacuum extraction is performed from a station higher than ±0. Even if delivery of the fetal head is achieved, subsequent birth trauma or shoulder dystocia may occur.

Regarding the third condition for vacuum extraction “engagement of the fetal head in the pelvic cavity”, the advanced part of the fetal head should descend below station ±0, or below station +2 especially for nulliparous women. The failure rate is significantly lower if the maximum circumference of the fetal head passes through the interspinous diameter of the ischiadic spine (station +4 or higher), regardless of parity. On the other hand, even if the advanced part is lower than station ±0, the maximum circumference of the fetal head may be above the position of the pelvic inlet due to malrotation or molding of the fetal head, and ultrasound examination is recommended particularly when internal examination cannot confirm the rotation of the fetal head or the station of the maximum circumference of the fetal head. Ultrasound confirmation has been reported to significantly reduce the possibility of misjudging the degree of fetal head descent, although no significant improvement in maternal and infant outcomes has been observed.4)

If the conditions for vacuum extraction cannot be confirmed due, for example, to sudden non-reassuring fetal status, it is recommended that the fetal status be described in detail in the medical record.

According to a previous study in the United States,5) the number of extractions in a successful vacuum-assisted vaginal delivery does not appear to be associated with an increased risk of neonatal complications, with no limit indicated as to the number of extractions (max observed: 6 times) or dislodgments (max observed: 5 times). However, the guidelines for obstetrical practice in Japan recommend that the total duration of vacuum application (i.e., time from initial extraction to the end of final extraction) should be 20 minutes or less, and that the total number of vacuum attempts (including cup dislodgement) should be 5 or less,1) partly to avoid the time-consuming decision-making process to ensure a forced delivery taking into account the perinatal outcomes. If it is predicted that the fetus will not be delivered during this time, or if the fetus does not deliver, the procedure should be switched promptly to forceps delivery or caesarean section. Vacuum extraction is performed in conjunction with labor contraction, and one contraction is counted as one extraction if there is no cup dislodgement; however, if cup dislodgement occurs and the cup is re-attached and re-extracted during one contraction, it is counted as two extractions in total.

The incidence of neonatal cephalhematoma increases with the increasing duration of vacuum extraction. Birth injuries also reportedly increase when vacuum application takes longer than 10 minutes from start to delivery, and the risk of intracranial hemorrhage in the fetus significantly increases when vacuum application takes longer than 30 minutes. Therefore, it is necessary to assess as early as possible whether vacuum extraction can reliably be performed to assist delivery.

Some studies have compared vacuum extraction and forceps delivery.6,7) Success rates of vacuum extraction have been reported to significantly differ from those of forceps delivery (e.g., 85% vs. 90%, odds ratio of failure rate of vacuum extraction to forceps delivery: 1.7) due to the lower extraction force of vacuum extraction compared with that of forceps delivery. Although vacuum extraction is associated with less increase in intracranial pressure in the fetus if extraction is performed in the correct direction, fetal complications such as intracranial hemorrhage, jaundice, scalp injury, neurological sequelae, and retinal hemorrhage have been reported to be more common with vacuum extraction than with forceps delivery. In contrast, facial nerve palsy and indentation and corneal injuries may occur following forceps delivery. On the other hand, maternal injuries such as severe perineal and/or vaginal lacerations as well as postpartum hemorrhage have been reported to be more frequent in forceps delivery than in vacuum extraction. Vacuum extraction can be performed without maternal injuries in cases of fetal malrotation, such as occiput-posterior position and transverse sagittal suture; however, the success rate of forceps delivery is higher compared with vacuum extraction, although it requires more skill. The incidence of shoulder dystocia is also significantly higher with vacuum extraction, especially in cases of extraction from a station higher than station ±0.

In sum, vacuum extraction and forceps delivery have different advantages and disadvantages, and neither method is better than the other. It is thus ideal to obtain informed consent for both methods if there is time to do so before forced delivery.

The guidelines for obstetrical practice in Japan recommend forceps delivery or caesarean section if the fetus cannot be delivered after a total duration of 20 minutes, or a total number of ≥5 times, of vacuum application.1) If an accurate diagnosis of the position and rotation of the fetal head can be obtained, and extraction along the pelvic guidance line perpendicular to the adhesive surface of the cup adsorbed to the flexion point of the fetal head is performed, vacuum extraction does not constitute a danger to the mother and/or fetus, even if the procedure is not completed. It should be noted, however, that time is definitely lost from the phase when forced delivery is required, and that vacuum extraction is often combined with uterine fundal pressure as an aid to delivery, but they can exacerbate fetal hypoxia over time.

Not only in vacuum extraction but also in forceps delivery, the descent of the head and the procedure should always be objectively assessed, and the decision should be made as to whether to continue or give up extraction. Therefore, if there is any doubt about internal examination findings, or in all cases of forced delivery, ultrasonographic confirmation of the status of the fetal head before and during vacuum extraction should be considered.6,7,8) As the incidence of vacuum extraction failing to result in delivery has been reported to be about 15%, it is recommended that vacuum extraction be performed in parallel with preparation for the next step of forced delivery, except in cases where the advanced portion of the head has reached a station of +4 to +5 without malrotation. Even if the next step of forced delivery is carried out smoothly, parallel preparation for neonatal resuscitation will be essential, because it will often be required.

If vacuum extraction is unsuccessful, the frequency of maternal injuries, subgaleal hematoma, and intracranial hemorrhage in the fetus will increase. Because cases of neonatal hemorrhagic shock 2 to 4 hours after delivery have been reported in neonates complicated by subgaleal hematoma, the neonate should be closely monitored for some time after delivery.9) In addition, maternal vital signs, blood loss, and the condition after repair of birth canal lacerations should be monitored more carefully following vacuum extraction than following normal delivery.9)

One of the serious complications observed in neonates undergoing vacuum extraction is subgaleal hematoma, which has been noted in a number of cause analysis reports in the Obstetric Care Compensation System (http://www.sanka-hp.jcqhc.or.jp/index.html), and there have been cases of hemorrhagic shock. Although no reliable method is available to prevent subgaleal hematoma, the guidelines for obstetrical practice in Japan recommend constant extraction along the pelvic guidance line, as the pathogenesis of subgaleal hematoma is associated with rocking and rotating movements in back and forth, left and right directions. Moreover, in cases where the procedure is switched from vacuum extraction to forceps delivery or caesarean section, the incidence of subgaleal hematoma, intracranial hemorrhage, and maternal injuries reportedly increases. In relation to these, early abandonment of vacuum extraction can lead to prevention of increased complications in both the mother and child. Therefore, it is recommended that subsequent vacuum extraction be abandoned if significant descent of the fetal head is noted after 2 or 3 extraction cycles and/or with repeated dislodgments.

Table 1 shows an overview of 6 cases covered by the Obstetric Care Compensation System for vacuum extraction switched to forceps delivery in 2018.10) In 5 of the 6 cases, malrotation of the fetal head in the fronto-anterior position was not diagnosed before the vacuum-extraction procedure was performed. The fronto-anterior position is known to have a greater influence on the fetal head than the occiput-posterior position, resulting in greater deformity of the fetal head. In addition, this fetal head position is often associated with caput succedaneum formation, and even if the advanced part of the fetal head descends to the pelvic outlet, the maximum circumference of the fetal head may be above the pelvic inlet. In other words, the fronto-anterior position may result in a higher maximum circumference of the fetal head than the occiput-anterior position, but the advanced part of the fetal head may be lower (Figure 2).8,10) During forceps delivery, the forceps blade is caught up on the maximum circumference of the fetal head, so the surgeon can feel that the station of the maximum circumference of the fetal head is high. However, because the vacuum cup is attached to the advanced part of the fetal head, it may be mistaken that the fetal head is descending if an accurate internal examination is not performed. Furthermore, during vacuum extraction, the progression of fetal head deformity and caput succedaneum formation may lead to the mistaken belief that the head is descending as a result of extraction. Ultrasound examination before vacuum extraction can help make an accurate diagnosis of the rotation and station of the fetal head, with follow-up observation by ultrasound during vacuum extraction also being an option.

| Indications for forced delivery | Outcomes of forceps delivery | Final delivery mode | Condition of the fetus before vacuum extraction |

| Non-reassuring fetal status | Complete delivery (3 times traction) | Forceps delivery | Before engagement in the pelvic cavity |

| Non-reassuring fetal status | Forceps could not be attached | Vacuum extraction | Malrotation (details unknown)* |

| Non-reassuring fetal status | Forceps could not be attached | Vacuum extraction | Fronto-anterior position* |

| Weak pain | Failure of forceps delivery | Vacuum extraction | Fronto-anterior position* |

| Non-reassuring fetal status | Failure of forceps delivery | Cesarean delivery | Fronto-anterior position* |

| Non-reassuring fetal status | Failure of forceps delivery | Cesarean delivery | Malrotation (details unknown)* |

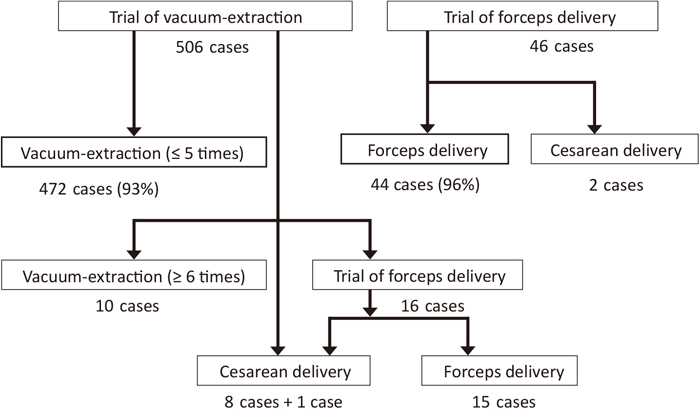

Figure 3 shows the outcomes of vacuum extraction or forceps delivery performed as the first procedure of assisted delivery at our previous institution, and Table 2 provides an overview of cases in which vacuum extraction was first attempted.11,12) During the study period, which preceded the publication of the guidelines for obstetrical practice in Japan,1) ≥6 extractions were performed in 10 cases, and success rates of vacuum extraction and forceps deliveries were 93% and 96%, respectively. An increase in the incidence of neonatal asphyxia was noted in cases where caesarean section was performed after unsuccessful vacuum extraction, while increases in the incidence of severe perineal lacerations and postpartum hemorrhage were observed when forceps delivery was performed after unsuccessful vacuum extraction. It took 10–20 minutes to proceed to emergency caesarean section, which may have contributed to the progression of fetal hypoxia. Fortunately, there were no cases of neurological sequelae in the neonates. Nevertheless, the advantages and disadvantages of each procedure should be taken into account in cases requiring assisted vaginal delivery.

| Successful vacuum extraction | Unsuccessful vacuum extraction | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extraction ≤5 times | Extraction >5 times | Cesarean delivery | Forceps delivery | |||

| Total number | 472 | 10 | 9 | 15 | ||

| Indication | ||||||

| NRFS | 129 (27%) | 2 (20%) | 5 (55%) | 5 (33%) | ||

| Malrotation | 41 (8.7%) | 4 (40%)* | 1 (11%) | 1 (6.7%) | ||

| Neonatal birth weight ≥3,500 g | 69 (15%) | 2 (20%) | 0 | 2 (13%) | ||

| Apgar score at 1 min | ||||||

| ≤3 | 8 (1.7%) | 0 | 3 (33%)* | 1 (6.7%) | ||

| ≤7 | 43 (9.1%) | 3 (30%) | 3 (33%) | 4 (27%) | ||

| Apgar score at 5 min | ||||||

| ≤3 | 3 (0.64%) | 0 | 1 (11%) | 1 (6.7%) | ||

| ≤7 | 11 (2.3%) | 1 (10%) | 3 (33%)* | 1 (6.7%) | ||

| Umbilical artery pH <7.1 | 25 (5.3%) | 0 | 2 (22%) | 1 (6.7%) | ||

| Neonatal complications | ||||||

| Cephalhematoma | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Subgaleal hematoma | 0 | 0 | 1 (11%)* | 0 | ||

| Facial nerve palsy | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Perineal laceration III | 21 (4.4%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Perineal laceration IV | 8 (1.7%) | 0 | 0 | 2 (13%)* | ||

| Total blood loss ≥1,500 ml | 4 (0.85%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (6.7%) | ||

This mini review highlights the most important aspect of training for vacuum extraction to assist delivery, that is, to ensure that internal examination findings, including the maximum circumference of the fetal head, the station of the advanced part, and the rotation of the fetal head, are obtained accurately before the procedure, as in the case of forceps delivery. The surgeon should train to visualize the descent of the fetal head and to perform extraction of the fetal head along the pelvic guidance line perpendicular to the cup attachment surface at the flexion point of the fetal head.