2019 Volume 6 Pages 38-55

2019 Volume 6 Pages 38-55

エジプト政府は2000年代初めに経済開発体制を見直し、市場主義に基づく成長という方向性を明確に打ち出した。規制を緩和し、グローバル経済に適応することで、持続的な経済成長を実現しようとするものだった。

ナズィーフ内閣で実践された経済改革によって、エジプト経済は2000年代半ばに成長局面を迎えた。ビジネス環境が改善し、対内直接投資と輸出が拡大したことで、四半世紀ぶりの高成長を記録した。その一方で、貧困率は2000年代に悪化した。なかでも、高成長だった2000年代後半に貧困率は大きく上昇した。

2011年の「1月25日革命」では、ナズィーフ内閣の政策運営はクローニー資本主義だったとして非難の的になった。しかし、その政策枠組みだった市場主義経済の下での成長という方向性は、革命後の政権にも引き継がれた。成長重視の方針は、政府が変わっても変更されることはなかった。

This research examines the state of development and progress in Egypt’s economic reform policies during the years 2000–2015. Additionally, this research answers the following: “What has the Egyptian economy achieved as a result of the economic reform?” and “What are the distinguishing features of the current Egyptian economy?” This research sheds light on the performance of the Egyptian economy in the 2000s.

Section 1 outlines Egypt’s long-term development trends in terms of growth and population. Besides economic growth, population-related issues present a persistent challenge in Egypt as these have substantial impact on human development. In recent years, population-related issues have become a major concern due to an increase in the population growth rate. Section 2 focuses on the socioeconomic developments that have influenced the people’s living standards. Section 3 examines the progress of development policies and identifies the basic stance of each government in terms of economic and fiscal management. Section 4 discusses salient aspects of Egypt’s economic development since 2000 based on the development performance and policies. Section 5 presents the conclusions.

This section examines Egypt’s long-term development trends using economic and population growth as basic indicators. It reveals the degree of expansion in size and number of these two indicators in the past quarter of a century.

1.1 GDP GrowthEgypt’s gross domestic product (GDP) was 2.8 times larger in FY 20151 than in FY 1990. The compound annual growth rate during that time was 4.15 percent. However, the growth rate fluctuated during those 25 years. After a crash in 1991, the economy recovered steadily until the late 1990s under the structural adjustment program, with the GDP growth rate averaging 4.3 percent in the 1990s. However, the economy slowed down in the beginning of the 21st century; its decline triggered by several external shocks such as regional instability and a decline in oil price.

The growth rate picked up in FY 2003 and reached a peak exceeding seven percent for the first time in 25 years a quarter-century in FY 2007–08 as shown in Figure 1.1. This high growth rate was mainly led by economic sectors that require specialized skills in technologically dense fields such as manufacturing, communication, or financial services; as well as capital intensive sectors that do not generate sufficient employment opportunities but require skilled labor (Ghanem 2009, 64−65). After the second half of 2008, the economy suffered the impact of the global financial crisis. As a result, it fell to a two percent growth rate after the January 25 revolution in 2011.

Egypt’s economic growth rate was recorded at its lowest since FY 1991 during the four years following the January 25 revolution. This was mainly attributable to political instability rather than economic policymaking yet most macroeconomic indicators deteriorated sharply. The economy faced double-digit fiscal deficits as well as a rising unemployment rate. The situation after the January 25 revolution was similar to that of the late 1980s, when the economy suffered from external imbalances as well as budgetary deficits.

Source: World Development Indicators

The population of Egypt in 2015 was 91 million, with an increase of 35 million since 1990. The annual population growth rate fell below two percent in the early 1990s but went up again from 2010. Specifically, the total annual population increase during the 20 years from 1990 ranged from 1.2 million to 1.4 million but accelerated to 1.9 million thereafter. The reasons behind the population increase are twofold: a rise in the birth rate as well as a steady decline in the death rate.

From a demographic transition perspective, Egypt entered into a stage of “demographic dividends” at the start of the 1990s, as shown in Figure 1.2. From 1993, due to declining birth rates, the proportion of working-age population (15–64 years old) out of the total population exceeded that of the previous year. This increase in the proportion of the working-age group relative to the size of the non-working-age population (14 years or younger and 65 years or older) presented a window of opportunity for economic growth in Egypt.

- Dependency ratio: Ratio of population aged 0-14 and 65+ per 100 population 15-64

Source: U.N. (2017) World Population Prospects: The 2017 Revision

However, the dependency ratio started to increase again from the end of the 2000s due to a rise in the birth rate. Considering the medium fertility variant as stated in the 2017 Revision of UN World Population Prospects, the dependency ratio is expected to rise until 2020 and fluctuate thereafter. It is projected to decline from 2020 until around 2040 before rising again for the next 20 years.

In most cases, the dependency ratio from the second half of the 2000s is expected to be lower than that of previous years. Although it remains high among lower middle-income countries where Egypt is classified, Egypt entered a period with low dependency ratio in the mid-2000s from a historical perspective. That is, from a demographic transition viewpoint, the Egyptian economy had an opportunity to accelerate growth and improve living standards since the late 2000s.

This section discusses the developments in socioeconomic indicators since the 2000s. The Egyptian economy experienced both high and low growth rates during this period. This section examines how far social indicators improved amidst economic fluctuations.

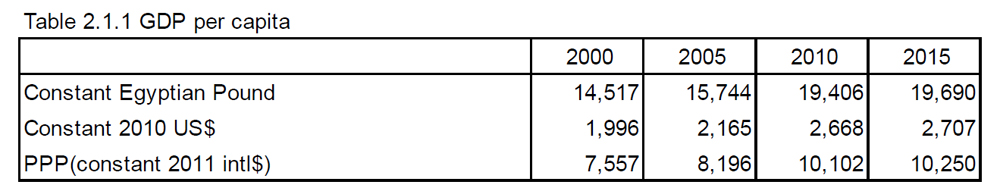

2.1. Macroeconomic IndicatorsAs the GDP growth rate increased in the 2000s (discussed in the previous section), per capita GDP also rose during this period. As shown in Table 2.1.1, GDP per capita increased by US$672 (constant 2010 US$) for an annual growth rate of 2.9 percent over the decade. However, GDP per capita has stagnated since 2010. The increase in GDP per capita for five years after 2010 was merely US$39 (constant 2010 US$) or an annual growth of 0.3 percent.

Source: World Development Indicators

Per capita income was not the only metric that showed slow development after 2010. The human development index (HDI) was also sluggish during 2010−15 (Table 2.1.2). Although the index improved slightly from 0.68 in 2010 to 0.69 in 2015, Egypt’s place in the world rankings fell from 101 to 111 in the same period. Meanwhile, Egypt’s HDI rose from 0.62 in 2000 to 0.68 in 2010, ranking 115 and 101 respectively. This means that human development in Egypt advanced relatively well in the first decade of the 21st century but stagnated since then.

Source: UNDP (http://hdr.undp.org/en/data)

Around 9.5 million people entered the workforce during the 15-year period after 2000. However, the number of employed people increased by only 7.6 million. This means that there were about 2 million more jobless laborers in 2015 than there were in 2000. The unemployment rate fluctuated during this period as shown in Table 2.1.3, that is, increasing in the first half of the 2000s from 9 percent to 11 percent before declining towards the end of the decade to 9 percent again. However, the unemployment rate increased from 9 percent to 12 percent in 2011 and remained high until 2015. Additionally, the youth unemployment rate (aged 15−24) was much higher than the overall rate. According to ILO estimates, the youth unemployment rate was 25, 30, 29, and 35 percent in 2000, 2005, 2010, and 2015, respectively. This infers that it is more difficult for new entrants into the labor market to find jobs. One reason for the high unemployment rate of the youth could be their job preferences. The government sector remained the preferred sector for the youth (Barsoum 2015, 110−111). For the highly educated, a government job is the first choice. This preference remained even though the government’s guaranteed employment scheme for people with education higher than secondary level was virtually ended many years ago. As a result, the unemployment rate is much higher among the highly educated compared to people with lower educational background (Table 2.1.3).

Source: Egyptian Statistical Yearbook, 2005, 2010, 2016, (CAPMAS)

Despite the slowdown in government hiring, the public sector is still a major employer in Egypt (Table 2.1.4). The public sector increased its employment by 1.4 million from 2000−2015. In 2015 there were 6.7 million employees in the public sector. The proportion of employees in the public sector is 27 percent of total employment.

Source: Egyptian Statistical Yearbook, 2005, 2010, 2016, (CAPMAS)

The millennium development goals (MDGs) list eight key goals for FY 2015. These goals were established following the adoption of the United Nations Millennium Declaration in September 2000. The MDGs had specific numeric targets applied to all UN member states. Like other member states, the Egyptian government has made a commitment towards achieving the MDGs since its inception. By its deadline in 2015, however, the results were mixed. Egypt succeeded in achieving some goals such as the gender parity index in primary school and reduction in child mortality but missed other targets. As shown in Table 2.2, the progress towards some goals has slowed or worsened since the second half of the 2000s.

(1) figure in 2004

(2) figure in 2012

(3) figure in 2014

Source: UN data (http://mdgs.un.org/unsd/mdg/Data.aspx), World Development Indicators, UNDP and Ministry ofPlanning (2015) Egypt's Progress towards Millennium Development Goals, UNICEF (2015) Children in Egypt: AStatistical Digest.

The first goal of the MDGs was to eradicate extreme poverty and hunger. In Egypt, the extreme poverty rate based on the national poverty line has not improved since the 2000s. Instead, it rose from 2.9 percent in 2000 to 5.3 percent in 2015. This means that, in 2015, there were about 4.7 million people unable to afford their basic sustenance despite spending all their income on food. Similarly, the national poverty rate also increased in the 2000s. After a drop from 24.3 percent in 1990 to 16.7 percent in 2000, the national poverty rate increased to 27.8 percent in the period from 2000−2015. Specifically, in 2015, there were about 25 million people living below the national poverty line. One reason behind the increase in poverty rate since 2000 could be the relatively high inflation rate during this period. In particular, the average rate of inflation in the second half of the 2000s was more than doubled compared with that of the previous 10 years. As a result, low income families, many of which are non-wage workers, faced difficulties in fulfilling their basic needs due to the rising cost of living.

Other MDGs were not fulfilled by 2015. The second goal, universal primary education, was not realized in Egypt. The net enrollment rate in primary education declined after the second half of the 2000s. After reaching 97.3 percent in 2005, the rate started to decline in the following years, reaching 90.6 percent in 2013. The other six goals yielded mixed results.

Some targets that were achieved by 2015 included the reduction in child mortality and tuberculosis death rates and establishing sustainable access to improved drinking water sources. These indicators have shown continuous improvement over the whole period since 1990.

2.3. Public FinanceEgypt has a chronic fiscal deficit. The overall fiscal balance has remained in deficit since the 1960s although it was close to being balanced during the mid-1990s (Ikram 2006, 158−163). The fiscal consolidation in the 1990s was part of a structural adjustment package supervised by the IMF. However, after a brief period of nearly-balanced budgets, the deficit as a proportion of GDP widened once more after 2000 to an average of 9.6 percent, varying between 6.8 percent in FY 2008 and 13 percent in FY 2013. Over this period, the ratio of total expenditure to GDP was relatively stable at around 30 percent. However, total revenue to GDP fluctuated, varying between 18.3 percent in FY 2012 and 27.1 percent in FY 2009. In particular, deficits after FY 2011 worsened due to stagnant revenues at a time of economic doldrums. Meanwhile, expenditures increased in response to people’s expectations. The development of the fiscal position is shown in Figure 2.3.1.

Source: The Financial Monthly (Ministry of Finance)

(1) Includes central goverment, local governments

The share of current expenditures, which is spending on goods and services consumed within the current year out of the total expenditure averaged 73 percent since the 2000s. The largest expenditure since the second half of the 2000s was attributed to subsidies, followed by salaries for government employees, and interest payments. The amount of subsidies and social benefits constituted around 30 percent of the total expenditure during the period (Figure 2.3.2).

Source: The Financial Monthly (Ministry of Finance)

Most subsidies consisted of allowances for food and energy. In particular, the energy subsidy constituted a substantial portion of the total cost during the period FY 2005−15, as shown in Figure 2.3.3. The official prices of oil products were kept artificially low even after Egypt became a net oil importer in the mid-2000s. For example, the official price of 80-octane gasoline was 0.9 Egyptian pounds (US$0.15) per liter in 2013. The government covered the difference between the international oil price and the official domestic price.

A notable change since 2011 is the increase in the ratio of expenditure on social benefits. Social benefits consist of social security benefits and social assistance benefits. The expenditures on both items increased since 2011 and became similar in magnitude to food subsidies after FY 2014.

Source: The Financial Monthly (Ministry of Finance)

This section examines the adjustments in economic policies since the latter part of Mubarak’s government. The Egyptian economy achieved high growth in the mid-2000s. However, after the January 25 revolution, as the economic conditions deteriorated, the government was forced to redefine the country’s economic policies.

3.1. Rise of Market Liberalism under the Mubarak GovernmentThe Egyptian government launched an extensive stabilization and structural adjustment program in 1991. This program, called the economic reform and structural adjustment program (ERSAP), was formulated under the supervision of the IMF and the World Bank in response to the Egyptian government’s request for assistance in solving Egypt’s debt crisis. In addition, as a reward for participating in the American-led coalition during the Gulf War in 1990, the Egyptian government accomplished a generous debt relief agreement with the Paris Club contingent upon the implementation of ERSAP.2

The main purpose of ERSAP was to restore macroeconomic stability. The principal measures for stabilization were (1) reduction of the fiscal deficit through tax and subsidy reform, (2) liberalization of interest rates, and (3) elimination of the multiple exchange rate system. These measures were not new to Egypt, but the country engaged in a series of reforms for the first time.

ERSAP also aimed to stimulate the private sector as an engine of economic growth. The government initiated legal reforms to promote private sector development. Some of the laws enacted included the new Public Enterprise Law (Law 203 in 1991), the Stock Market Law (Law 95 in 1993), the Investment Law (Law 8 in 1997), and the Company Law (Law 3 in 1998).

The implementation of ERSAP resulted in a rapid recovery of the macroeconomic landscape. By the mid-1990s, the government’s deficit was reduced to two percent of GDP. International reserves expanded six-fold to US$20 billion and the inflation rate decreased to less than five percent (El-Ghonemy 2003, 80−83). The privatization of state-owned enterprises, which was the highlight of the structural adjustment package, accelerated in the mid-1990s. A total of 130 state-owned enterprises were privatized from 1993 to 2001. Because of the implementation of ERSAP, Egypt managed to slip out of its debt crisis and achieve more than five percent growth in the late 1990s.

By the early 2000s, however, the momentum of economic reform dissipated and the economy stagnated. The budget deficit once again deteriorated and surpassed the level before the implementation of ERSAP. Difficulties in the balance of payments also surfaced mainly due to external shocks such as the Asian financial crisis and growing tensions in the region. To break the economic downturn, new and extensive economic reforms were discussed within the National Democratic Party (NDP). The basic idea was to further open up the economy in order to attract foreign investment and promote exports. The new cabinet inaugurated in July 2004 and headed by Ahmed Nazif implemented a fresh economic reform policy.

The Nazif cabinet reinvigorated the economic reforms that had stalled in the early 2000s. The new economic reforms aimed to create a business-friendly environment in order to attract foreign investments. The first measure was to reduce customs and taxes. The weighted average of tariff rates was reduced from 14.6 percent to 9.1 percent. The new Income Tax Law (Law 91 in 2005) reduced personal and corporate income taxes by up to 50 percent and applied a new maximum rate of 20 percent to both personal and corporate income taxes. Other key measures that encouraged a pro-business environment included a consolidation of the financial sector and an acceleration of the pace of privatization. Among the highlights of the new privatization program were the IPO of 20 percent of the government’s stake in Telecom Egypt in 2005 and the sale of one of the four biggest state-owned banks (Bank of Alexandria) in 2006.

These economic reform policies, coupled with improved international economic circumstances, contributed to Egypt’s economic recovery in 2006 to 2008. The GDP growth was around seven percent during these years, up from an average of three percent in 2001 to 2003. Gross FDI inflows increased to about 10 percent of GDP in 2006 to 2008, up from one percent in 2001 to 2003.

Although the GDP growth rate declined after the second half of 2008 due to the global economic crisis, Egypt “weathered the global financial crisis relatively well” (IMF 2010, 6). The spillovers of the global financial crisis were limited in the case of Egypt since its domestic financial sector was not yet well-integrated into the global market. Moreover, the government provided a sizable fiscal stimulus package in 2009 in order to promote investment. In addition, the Central Bank of Egypt cut the policy rate six times in 2009. Accordingly, GDP growth picked up in the second half of 2009.

3.2. Confusion in the Revolutionary PeriodAfter the revolution in 2011, the Egyptian economy came to a standstill. The annual economic growth rate during the FY 2011−15 period averaged 2.5 percent. The unemployment rate in 2011 escalated to 12 percent from 9 percent in the previous year. FDI inflows and foreign tourist arrivals also declined significantly due to widespread strikes and political instability.

The Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) assumed power as a transitional government following the collapse of the Mubarak regime. Although the primary economic role of the transitional government was to promote recovery from economic turmoil, it “refused to undertake necessary reforms to strengthen the economy” (El Dahshan 2016, 203). What the government did was resort to populist measures to appease the public. For example, it approved 450,000 permanent contracts for temporary workers in the public sector and increased their wages. The transitional government, however, rejected a US$3-billion loan offer with favorable terms from the IMF. As a result, the fiscal deficit increased to 10.1 percent of GDP in FY 2012, and by mid-2012, foreign reserves fell by almost 50 percent compared to their level before the 2011 revolution.

The government of Muhammad Morsi (elected in the June 2012 presidential election) tried an austerity approach to stabilize the economy. The government planned a fiscal consolidation through tax increases and subsidy cuts and requested US$4.8 billion in IMF loans in August 2012. However, in December of the same year, the Morsi government sought to delay the IMF loan and withdrew the fiscal consolidation measures. Fiscal consolidation was in fact never implemented during the Morsi government. Similarly, the long-term development plan dubbed “Renaissance Project” announced by President Morsi as his election platform never materialized. The Morsi government failed to implement economic reform policies because the economy was put on the back burner during his term in office.

The appointment of the interim President Adly Mansour in July 2013 changed the course of Egypt’s economic policies. The receipt of US$12 billion in economic assistance from the Gulf Arab countries enabled an expansionary fiscal policy to boost growth. Ahmed Galal, then finance minister, announced a plan to put the economic stimulus package ahead of fiscal consolidation. In fact, the interim government implemented two stimulus packages worth US$9 billion within a year.

The direction of Egypt’s monetary policies was also changed. The overnight lending rate was reduced in August, September, and December of 2013, reaching 9.25 percent, which is 1.5 percentage points lower than the March 2013 level. This series of reductions was the first since 2009. The Central Bank prioritized boosting investment over keeping inflation in check. However, despite concerted efforts by the interim government and the Central Bank, GDP growth remained sluggish at two percent and unemployment rate deteriorated further to 13 percent.

3.3. Economic Revitalization Attempts under the Sisi GovernmentSoon after assuming office in June 2014, President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi gave instructions to amend the draft budget for FY 2015. This budget represented a policy shift once again in that the Sisi government returned to fiscal austerity. The deficit target in the amended budget was 10 percent of GDP—two percentage points lower than the earlier version. To reduce the budget deficit, the government cut energy subsidies and raised taxes. Cutting subsidies was deemed politically challenging and successive governments hesitated to put it into practice. By implementing bold energy subsidy reforms immediately after the inauguration, the Sisi government distinguished itself from previous governments. The Central Bank also reversed its monetary policy in concert with the government. The overnight lending rate was increased by one percentage point in July 2014 to curb inflation (Central Bank of Egypt, 2014). The rate was again increased by 0.5 percentage point in December 2015 after cutting the rate by 0.5 percentage point in January 2015. This showed that an overriding goal of the Sisi government is to contain inflation before promoting investment.

For its mid- and long-term development strategies, the Sisi government embarked on megaprojects such as the development of the Suez Canal area, construction of a new administrative capital, and launch of a new agricultural reclamation project. In addition, the government held an international conference in March 2015 to attract foreign investment. During this conference named Egypt Economic Development Conference (EEDC), the government announced a new five-year macroeconomic framework and an ambitious 15-year development strategy. The goal of the new five-year framework, called “Strat_EGY,” is to restore macroeconomic stability through fiscal consolidation, infrastructure development, and sustainable social policies. Meanwhile, the goal of the 15-year development strategy, titled “Sustainable Development Strategy: Egypt’s Vision 2030,” is as follows:

By 2030, Egypt will be a country with a competitive, balanced, and diversified economy, depending on knowledge and creativity, and based on justice, social integration, and participation, with a balanced and varied ecosystem… Moreover, the government looks forward to lifting Egypt, through this strategy, to a position among the top 30 countries in the world, in terms of economic development indicators, fighting corruption, human development, market competitiveness, and the quality of life. (Ministry of Planning, 2015)

Economic policymaking under the Sisi government is similar to that of the Mubarak government in the late 2000s. The main objectives are to maintain macroeconomic stability and to promote foreign investment. Additionally, the Sisi government started taking measures to address subsidy reforms. However, Egypt still faced huge fiscal deficit and high unemployment rates in 2015 amid security concerns.

This section specifies the distinguishing features of the Egyptian economy since the year 2000, based on analyses provided in the previous sections. It identifies five features which characterize the Egyptian economy during this period.

4.1. A Vulnerable EconomyThe Egyptian economy is vulnerable to shocks from external factors. For example, the ratio of FDI inflows to GDP averaged 5.9 percent during 2005−15. Inward FDI is considered a critical factor in job creation especially in high value-added industries. However, as the volume of FDI differs significantly depending on the year, the economy has been at the mercy of changing trends in FDI. While the volume of FDI inflow accounted for more than 10 percent of the GDP in 2007−08, it was less than four percent in 2013−15. Consequently, the gross investment rate of the economy diminished markedly from 22.4 percent of the GDP in FY 2008 to 13.8 percent in FY 2014. The fluctuations in FDI inflows have significantly affected the investment rate of the economy because of weak domestic investments.

Foreign exchange has also influenced the economy, especially through government revenues. The government’s main sources of foreign exchange earnings include oil-related revenues,3 the Suez Canal transit fees,4 and grants from foreign governments. These earnings constitute the so-called rent revenue from Egypt’s assets. The average rent revenue during the period from 2006−2015 was 33.6 percent of the total government revenues. However, it fluctuated due to external factors such as international oil prices and Egypt’s political relations with other countries. For example, the share of rent revenue decreased from 43.3 percent of the total revenue in 2014 to 26.9 percent in 2015. Because of the chronic fiscal deficit, the decline in government revenue negatively affected Egypt’s whole economy for a few years. The deterioration of fiscal balance prompted the government to implement austerity measures.

The volatile inflation rate is another source of economic fluctuation. When international grain prices soared in 2008, the domestic inflation rate in Egypt escalated to more than 20 percent as shown in Figure 4.1. With Egypt importing about half of its overall consumption of wheat, the change in international wheat prices affected general consumer prices to a considerable extent.5 Alarming food shortage escalated during this time. The government responded by expanding the food subsidy program. The inflation rate gradually dropped to below five percent from 2010 to the end of 2012, which was the lowest in 10 years. However, it increased thereafter and hovered around 10 percent despite continued economic stagnation.

Source: The Financial Monthly (Ministry of Finance)

The implementation of ERSAP sent a clear signal that the Egyptian government accepted the fundamental principles of market mechanism. In the mid-1990s, the government embarked upon the consolidation of state-owned enterprises (SOEs). Privatization of SOEs is one of the mainstream policy measures advocated by the IMF for countries suffering from a large and inefficient public sector—such as Egypt. Hence, undertaking the privatization program became inevitable for Egypt to meet the IMF’s requirements.

The framework of Egypt’s economic policy after the implementation of ERSAP fell within the scope of the so-called “Washington Consensus.” At the beginning, the government had little choice but to follow the economic reform measures advocated by the IMF and the World Bank. However, despite the economy showing signs of recovery, the government continued active efforts toward the reform program. Unlike during the 1980s, the Egyptian government took a proactive stance on the economic reform measures set by the IMF and the World Bank in the 1990s.

In the mid-2000s, the Egyptian government accelerated its effort towards market-oriented reforms. The main purpose of these reforms was to win the approval of international development organizations such as the IMF and the World Bank. The government believed that a pro-reform image for the country would help attract foreign investment. Although the government considered the timing and sequence of the reform, the reform strategy itself was almost identical to what was advocated by the IMF and the World Bank in ERSAP. This made policymaking in the 2000s quite predictable, being a reiteration of the scenario in the 1990s. Hence, its framework followed international standards.

4.3. Growth-oriented PolicyThe Egyptian government’s priorities in the 2000s aimed at first accelerating the country’s economic growth before reducing poverty. The purpose of the renewed strategy formulated by the NDP in the early 2000s was to revive the stalled economic reforms in order to increase FDI and create jobs.

In the turbulent period after 2008, the government reacted by providing fiscal stimulus to revitalize the economy while temporarily postponing fiscal consolidation. The government undertook an additional expenditure of about two percent of the GDP to invest in infrastructure projects. Even after the January 25 revolution, the government placed priority on economic recovery before expanding social security-related expenditures. For example, in 2013, the Mansour interim government implemented two stimulus packages within a year as mentioned in Section 3.2. Since the 2000s, the government has pursued this growth-oriented economic policy as its top priority.

On the other hand, the social welfare policy was neglected for quite some time. While Egypt maintained an extensive subsidy system for several goods and services, such as energy, food, and public transport for many decades, this system was clearly unsustainable and ineffective. However, the successive governments were reluctant to modify the subsidy system in any form because it was a politically sensitive issue. They were aware that the subsidy reform would face strong criticism from the public, just the way it did in 1977. Consequently, the subsidy program was left untouched and no other social welfare policy was developed. No major subsidy reforms were initiated until late 2014.

4.4. Ineffective PlanningAlthough the government placed a priority on economic growth, the strategic development plans were sometimes unreliable and uncontrolled. The government formulated several mid- and long-term development plans. The mid-term plans were five-year plans issued every five years since the early 1980s.6 Each five-year plan included investment projects with numerical targets and annual expenditure plans. For example, one of the goals of the sixth five-year plan (FY 2007−12) was to increase the investment rate from 20 percent to 24 percent of the GDP. Towards this end, the government planned institutional reforms as well as allocated 159 billion Egyptian Pounds, equivalent to 12 percent of the total expected investment (Ministry of Economic Development 2007, 79).

The government also laid out long-term development plans since the 1980s. However, several long-term development plans overlapped with previous plans without annulling the older ones or making a clear demarcation between these plans. For example, two comprehensive long-term development plans existed simultaneously in the 2000s. The first one was “Egypt and the 21st Century” (FY 1998−2017) and the second, “Long-term Socioeconomic Development Vision” (FY 2003−22). The reason for their coexistence was that different cabinets formulated these plans. Although the latter plan was announced after the former, this did not mean that one was a revised version of the other. The former long-term plan was referred to by some government documents as a benchmark after the publication of the latter plan. In fact, there was little inconsistency between the two in terms of the direction of development. However, there was confusion caused by different numerical goals and points of focus between the two plans.

In addition, the predetermined numerical indexes in the mid- and long-term plans were sometimes revised or replaced by the subsequent documents without any justification. While it is reasonable to modify a plan in response to changes in circumstances, revising a plan impulsively and without notification undermines its credibility. As such, it is understandable that the mid- and long-term plans did not draw much attention from the public. Furthermore, the government designed development plans without thorough consultation with stakeholders. As a result, most mid- and long-term plans were not regarded as doctrines of economic development.

4.5. Domination of Big BusinessesSince the 1990s, the private sector’s share in Egypt’s total output has increased. In particular, the expansion of big private companies drew attention from investors in the 2000s. In fact, the total annual revenues of the top ten companies listed in the Egyptian Stock Exchange (EGX) increased from four percent of the GDP in 2000 to 10 percent in 2010. If some big, unlisted companies were taken into account, the share of big businesses would be much higher.7 It is worth noting that the share of small and medium-sized manufacturing enterprises (SMEs) in net private manufacturing value-added industries was only about 7.5 percent at the end of the 1990s (El-Kabbani and Kalhoefer 2011, 1). The same trend applied to bank loans. The share of SMEs in total loans was about five percent at the end of the 2000s (Rocha et al. 2010, 47).

In the 2000s, big private businesses, most of which are family-owned, took an active role in politics. Leading businesspeople increasingly entered politics as ministers or members of the national parliament. The Nazif cabinet (2004−11) appointed top-ranked business owners as ministers of business related ministries such as trade and industry, tourism, housing, agriculture, and health. The businessman-turned-minister phenomenon promoted further deregulation of the industry in Nazif’s ministry. Consequently, the Nazif cabinet was regarded as reform-oriented as well as business-friendly. Big business owners were represented in the NDP more in the 2000s than in previous years. As a result, the NDP became an increasingly pro-business party. However, in addition to creating a business-friendly economy, a number of prominent businessmen-turned-politicians exploited their political power for their own business interests in the crony capitalism environment. It has been quoted that “many Egyptians saw big businesses as the epitome of an unholy marriage between power and wealth, between politics and the economy” (Adly 2014, 5). Big businesses dominated not only economic activity but also domestic politics during the Nazif Cabinet.

The dominance of big businesses in the political scenario ended after the January 25 revolution. A number of ministers from big businesses were prosecuted on corruption charges, and the parliament was dissolved. The NDP, too, disbanded by a court order. Instead, the military, which had an arm’s length relationship with big private businesses, took up the position and managed the politics thereafter. As a result, the link between politics and big businesses was disrupted, and the latter lost its political clout.

However, after the Revolution, successive governments did not necessarily project a hostile attitude towards big businesses but rather, encouraged them to resume investments. Since every government after that of Mubarak’s maintained a market-oriented economic mechanism to revive the flagging economy, private investments became indispensable. In brief, big businesses became too big to ignore even after their political decline. Big businesses play an indispensable role in the economy even after the Revolution.

The Egyptian economy has undergone various fluctuations since the 2000s; in particular, it faced turbulence after 2008. The annual growth rate during 2000–2015 ranged from 1.8 to 7.2 percent. In the beginning of the 2000s, the economy was in a slump; hence, economic reform momentum was stalled. By revitalizing economic reform through Nazif’s cabinet, the growth rate recovered, with its peak observed in the past quarter century. After 2008, however, the economy slowed down again due to external shocks and further deteriorated due to the political upheaval in 2011.

In spite of high economic growth in the mid-2000s, human development progressed slowly. The economic slump after the January 25 revolution in 2011 worsened the situation. Consequently, Egypt fulfilled only a part of the MDGs by 2015. In reality, the government did not focus much on improving human development in the 2000s. The priority was to enhance the country’s economic growth. In other words, the government pursued a growth-oriented economic policy. Although the strategic growth plans were sometimes too immature to be enforced, the Egyptian government actively followed the internationally pervasive policy prescription for economic growth. The main principles included macroeconomic stability and deregulation, which favored the interest of large private businesses. Even after the January 25 revolution, the fundamental framework of the country’s economic development policy did not change although there were frequent changes in the government within a short span of time.