2025 Volume 2 Issue 5 Pages 81-85

2025 Volume 2 Issue 5 Pages 81-85

This study focused on the association between malnutrition, income, and living alone among residents of a large-scale housing complex in Japan to clarify the relationship between household food insecurity and social isolation. We adopted a cross-sectional research design and conducted a survey by means of a self-administered questionnaire. Subsequent logistic regression analysis showed that social isolation and subjective household financial hardship were statistically independent risk factors for food insecurity (males had respective ORs of 2.79 and 8.80; females respective ORs of 2.31 and 8.66). We showed that in addition to general financial support, support catering specifically to social isolation is needed to address food insecurity among residents of this housing complex.

The present study’s protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Mukogawa Women’s University. This cross-sectional study employed self-administered questionnaires to conduct a survey. It was conducted in late June 2023 in Mukogawa Danchi, Nishinomiya City, Hyogo Prefecture in the Osaka–Kobe metropolitan area in a large-scale housing complex that was constructed in the 1970s. As of September 2023, the housing complex had a population of approximately 20,000, with 8.9% under the age of 14 and 35.8% over the age of 65; it therefore has a declining birthrate and an aging population compared to the respective national average values for Japan (11.5% under the age of 14 and 29.1% over the age of 65).

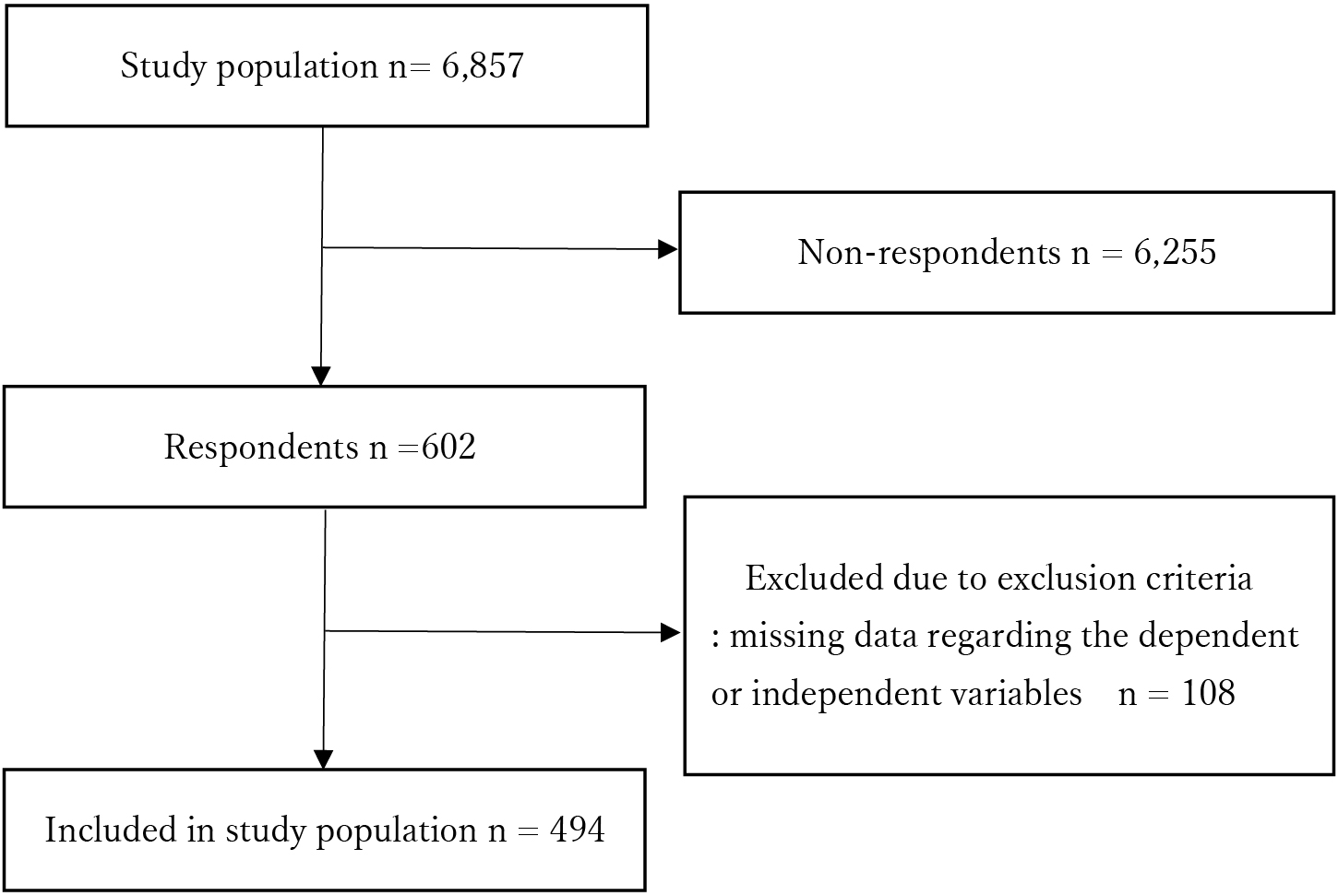

A flow diagram of the sample collection procedure is shown in Fig. 1. Survey participants were all residents of the housing complex we surveyed and data from 494 households of the total of 6,857 households in the housing complex were used for analysis. Out of these, the response rate was 8.8%, and out this total response rate, the valid response rate was 82.0%. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Food security status was evaluated using the Japanese version of the U.S. Household Food Security Survey Module: Six-Item Short Form1). Food insecurity refers to the limited or uncertain availability of, or ability to obtain nutritionally adequate and safe food in a socially acceptable manner2).

According to the user notes, scores of 0–1 were categorized as food secure, whereas scores of 2–6 were categorized as food insecure3). Social isolation was evaluated using the Japanese version of the Lubben Social Network Scale, shortened version (LSNS-6)4). We also recorded the following: age, sex, years of residence in the housing complex, number of family members, presence of children (number of children under the age of 18 years in the household), and income. Income was divided into three categories: less than 2, 2–5.99, and 6+ million Yen. Subjective household financial hardship was assessed using four categories: very worried about the lack of leeway, not sufficient leeway and somewhat worried, no leeway but not worried, there is leeway. Furthermore, the former two groups were combined into the “hardship” group, and the latter two groups into the “no hardship” group. These groups were then used in the analysis.

The relationship between food insecurity and social isolation was analyzed separately for males and females by means of logistic regression. Model 1 was unadjusted; Model 2 adjusted for age, sex, years of residence, number of family members, and presence of children, with income added as an independent variable. In Model 3, the independent variable of income in Model 2 was substituted with subjective household financial hardship. Collinearity was diagnosed before analysis, and no relationship with a Variance Inflation Factor greater than 2 between the independent variables was found.

Prior to this study, we reported on the relationship between food security and, respectively, dietary habits, subjective sense of health, and subjective sense of well-being in the housing complex5). According to our survey,

17.5% of participants experienced food insecurity. It was confirmed that households with food insecurity tend to have insufficient dietary intake and a tendency for subjective health and well-being to be low depending on participant age.

In addition, the report found that 70.8% of food insecure residents suffered from social isolation, which was significantly higher than the 44.2% of food secure residents (p < 0.001).

Table 1 shows the results of the logistic regression analysis with food insecurity as the dependent variable. The results showed that social isolation and subjective household financial hardship (with odds ratios [OR] of 2.79 and 8.80, respectively) were statistically independent risk factors for food insecurity among males. There was no significant association between income and food insecurity. For females, social isolation and low income (ORs of 3.08 and 4.26, respectively) as well as social isolation and subjective household financial hardship (ORs of 2.31 and 8.66, respectively) were each statistically independent risk factors for food insecurity.

| Food security | Food Insecurity | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95%CI | OR | 95%CI | ||

| Male n (%) | 128 (80.5) | 31 (19.5) | |||

| Model 1 | |||||

| Social isolation | 1.00 | [Reference] | 2.44 | [1.05–5.72] | 0.039 |

| Model 2 | |||||

| Social isolation | 1.00 | [Reference] | 2.71 | [1.04–7.07] | 0.041 |

| Low Household income | 1.00 | [Reference] | 1.89 | [0.79–4.49] | 0.151 |

| Model 3 | |||||

| Social isolation | 1.00 | [Reference] | 2.79 | [1.06–7.36] | 0.038 |

| Subjective household financial hardship | 1.00 | [Reference] | 8.80 | [3.21–24.13] | 0.000 |

| Female n (%) | 277 (82.7) | 58 (17.3) | |||

| Model 1 | |||||

| Social isolation | 1.00 | [Reference] | 3.40 | [1.84–6.28] | 0.000 |

| Model 2 | |||||

| Social isolation | 1.00 | [Reference] | 3.08 | [1.56–6.08] | 0.001 |

| Low Household income | 1.00 | [Reference] | 4.26 | [2.13–8.50] | 0.000 |

| Model 3 | |||||

| Social isolation | 1.00 | [Reference] | 2.31 | [1.17–4.57] | 0.015 |

| Subjective household financial hardship | 1.00 | [Reference] | 8.66 | [3.99–18.77] | 0.000 |

OR: odds ratio. CI: confidence interval

Model 1: unadjusted

Models 2 and 3: adjusted for age, years of residence, household size, and the presence of children.

Reference for independent variable of income is an income greater than 2 million yen.

Reference for subjective household financial hardship is “no hardship”

These results show that social isolation is a statistically independent risk factor for food insecurity in both males and females. We infer that social isolation limits support from surrounding people in terms of access to and provision of food, which contributes to food insecurity. Practices that provide support for food insecurity by reducing social isolation have been effectively implemented6); implementation of similar practices is needed for residents of large-scale housing complexes in Japan.

Interestingly, the sole household indicator associated with food insecurity among males is not income, but subjective household financial hardship. This suggests that males do not make effective use of their household income for food. Sex-based differences in the perceived value of food are known to exist; for example, males have a higher proportion of commercially prepared food expenditure than females7), and females emphasize healthy eating more than males8). Even when men have a high income, they might prioritize other expenses over food and engage in high-cost consumption behaviors, such as eating out and buying prepared foods.

In the United States, specific support covering food costs is provided as a social security benefit9). Similarly, in Japan, in order to ensure food security for residents in large-scale housing complexes, it is important to establish a social security system that directly provides food, regardless of the beneficiaries’ ability to manage their household finances. this is considered an effective method of securing food.

Furthermore, to prevent social isolation, it is necessary to strengthen monitoring systems, secure places for interaction, and create communities in which people can feel a sense of connection. Previous research on food insecurity has mostly investigated the association between nutritional status and disease10,11), but the relationship between the former and social isolation remains unclear.

The results of this study clarifies the association between household food security and social isolation and provides valuable insights that should prove useful in considerations regarding social security measures for residents of large-scale housing complexes in Japan.

However, our results are based on survey results from among residents of a single housing complex in a local city in Japan and cannot be generalized. Additionally, the low survey response rate of 8.8%, which may be a cause of concern over the possible presence of a characteristic bias between respondents and non-respondents, may lead to sampling bias. In future studies, to further clarify the actual circumstances and factors associated with food insecurity among Japanese households nationwide, it will be necessary to expand the target area and conduct large-scale surveys to enhance our understanding.

Social isolation and subjective household financial hardships among residents of large housing complexes with an aging population are statistically independent risk factors for food security. Low income was a factor associated with food insecurity for females, but not males.

This study showed that not only financial support, but also support for social isolation is needed to address food insecurity among the residents of this housing complex.

We would like to thank the residents of the Mukogawa housing complex, who participated in the survey, and the residents’ association, which provided advice on survey implementation.

This research was conducted with support from the Nippon Life Insurance Foundation.

Wakimoto K. and Fujita Y. pioneered the study and developed the statistical analysis plan. Wakimoto K. and Hisanari M. analyzed the data. Wakimoto K. prepared the first draft of the manuscript; Hisanari M., Fujita Y., Ohtsubo A., Fujii T., Kato J., Ogasawara H., Kudo D., Fukui M. contributed to the writing of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the final version of the manuscript and came to an agreement.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest concerning the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.