Abstract

INTRODUCTION: Pancreatic mucinous cystic neoplasm (MCN) is a cystic tumor of the pancreas typically located in the pancreatic body or tail in middle-aged women. However, MCN rupture is rare. This report describes a case of MCN with spontaneous rupture during follow-up.

CASE PRESENTATION: The patient was a 34-year-old woman. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a 130 mm multifocal cyst in the pancreatic tail. The cyst, characterized by multiple septa and cyst-in-cyst structures, was diagnosed as an MCN. Initially, the patient opted for periodic follow-ups instead of surgical resection. After a gradual increase in cyst size, surgery was scheduled approximately 1 year later. Two days before the scheduled surgery, the patient experienced unexplained lower abdominal pain. Moreover, CECT revealed a shrinking cystic mass in the pancreatic tail along with the presence of ascites, leading to a diagnosis of spontaneous rupture of the pancreatic cyst. No peritonitis was detected, and a distal pancreatectomy was performed 2 days after admission. Pathological examination confirmed that the pancreatic cyst was a noninvasive mucinous cystadenocarcinoma. The abdominal cavity contained large amounts of turbid ascites with neutrophils but no bacterial growth. Strong inflammatory changes were noted at the cyst wall disruption site. Despite the development of a pancreatic fistula (ISGPF Grade BL, Clavien–Dindo Grade II), the patient was discharged from the hospital on postoperative day 16 and remained alive and recurrence-free for 18 months after surgery.

CONCLUSION: Spontaneous rupture of an MCN is rare. In this study, we report our case and review previously published cases of MCN rupture. We also discuss the potential causes of the spontaneous rupture in our case.

Abbreviations

CECT

contrast-enhanced computed tomography

DP

distal pancreatectomy

ISGPF

International Study Group on Pancreatic Fistula Definition

MCA

mucinous cystadenoma

MCC

mucinous cystadenocarcinoma

MCN

mucinous cystic neoplasm

MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

OTS

ovarian-type stroma

PD

pancreaticoduodenectomy

PgR

progesterone receptor

SPDP

spleen-preserving distal pancreatectomy

INTRODUCTION

Mucinous cystic neoplasms (MCNs) are polycystic pancreatic tumors lined with mucin-secreting epithelial cells and characterized by ovarian-type stroma (OTS). MCNs are almost exclusively located in the body or tail of the pancreas in middle-aged women.1) MCN rupture is rare due to the presence of a thick fibrous capsule.2) In this report, we present a case of spontaneous rupture of the MCN without any specific trigger and describe our approach, including distal pancreatectomy (DP).

CASE PRESENTATION

A previously healthy 34-year-old woman with no significant medical history presented to her physician with the chief complaint of epigastric discomfort. Although the patient’s symptoms improved with medical treatment, abdominal ultrasonography revealed a 130 mm mass in the pancreatic tail. She was referred to the Department of Gastroenterology of our hospital for further evaluation. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) showed a multifocal cystic mass with a length of 130 mm in the pancreatic tail, with multiple septa and a cyst appearance consistent with a pancreatic MCN. The mass compressed the stomach and colon but showed no significant hemorrhage, calcification, or main pancreatic duct dilatation (Fig. 1).

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a multifocal cyst with a diameter of 130 mm bulging from the pancreatic tail to the left abdomen. T2-weighted images indicated that the cyst contents had signal intensities similar to water, with some septal walls appearing thick but no mural nodules. As with CECT findings, there was no significant dilatation of the main pancreatic duct or lymph node enlargement (Fig. 1).

Based on these imaging test results, we suspected that the cyst was a pancreatic MCN. The patient was referred to our department for further surgical treatment. Despite our recommendation for surgery, she preferred close monitoring. Approximately 1 year after the initial diagnosis, she decided to undergo surgery owing to an increase in the cyst size (Fig. 2).

Two days before the scheduled surgery, the patient presented to the emergency department with abdominal pain. She presented with spontaneous pain and tenderness in the upper abdomen but no peritoneal irritation symptoms. Blood tests showed mildly elevated inflammatory and pancreatic enzyme levels. CECT indicated a shrinking cystic mass in the pancreatic tail and ascites, suggesting a ruptured pancreatic cyst (Fig. 3). No trauma or other triggers were observed before the onset of abdominal pain, leading to the diagnosis of spontaneous rupture of the MCN. Considering her stable general condition without peritonitis or hemorrhage, a DP was performed on the initially planned day, 2 days after admission.

Surgical findings included the operative time of 190 min and blood loss of 50 mL, with no requirement for transfusion. The abdominal cavity contained a large amount of turbid fluid. Rapid intraoperative cytological examination of the ascites was negative (CY0), and cultures showed no bacteria growth. A huge mass was observed in the left upper abdomen, covered by the greater omentum, with adhesions to the posterior wall of the stomach and transverse colon mesentery. The dorsal pancreas was tunneled via blunt dissection of the anterior surface of the portal vein from the inferior border of the pancreas. The splenic arteries and veins were ligated and dissected. The pancreas was resected along the portal vein path using an endoscopic linear stapler. The dorsal pancreas was dissected, the adhesions of the greater omentum and the colonic mesentery to the tumor were detached without damaging the mesenteric vessels, and the excised specimen revealed a 150 mm-sized cystic tumor with multifocal interiors (Figs. 4 and 5). A rupture hole, approximately 3 mm in diameter, was detected on the ventral side of the largest cyst. The fluid from the ruptured cyst was cloudy yellow, while the non-ruptured cyst fluid was clear with slightly yellowish mucus. Cytology of both fluids showed no malignant cells (class II), and cultures were negative.

Fig. 4

The surgical findings: (A) A huge mass is observed in the left upper abdomen, covered by greater omentum, with adhesions to the posterior wall of the stomach and transverse colon mesentery. (B) The pancreas was resected along the portal vein path using an endoscopic linear stapler.

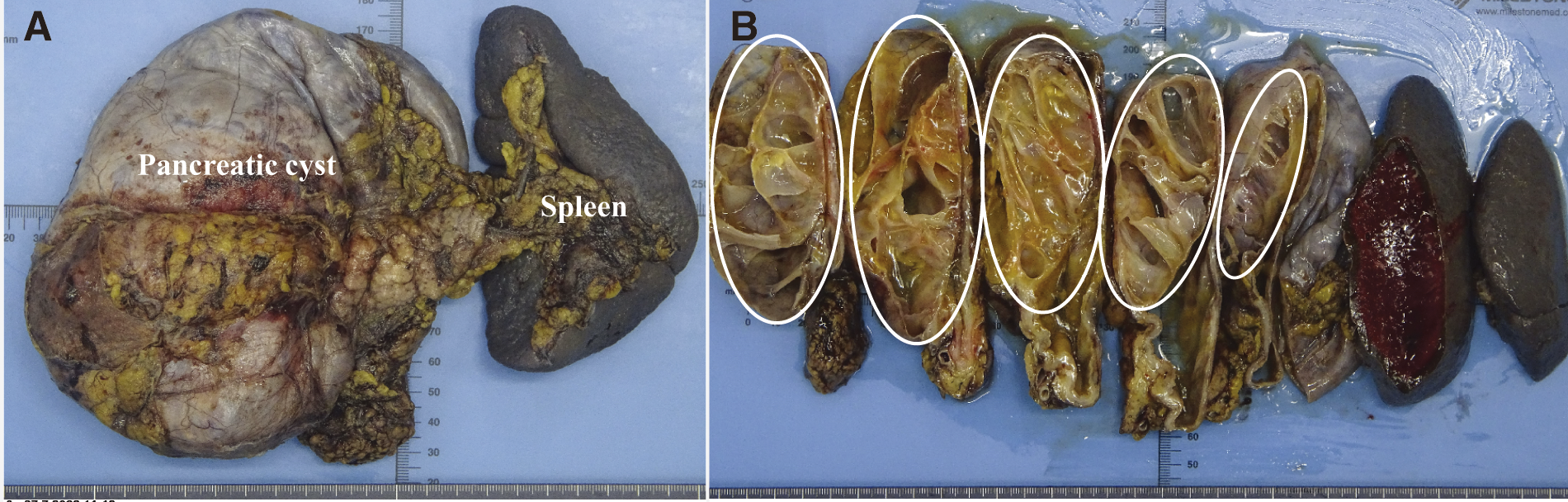

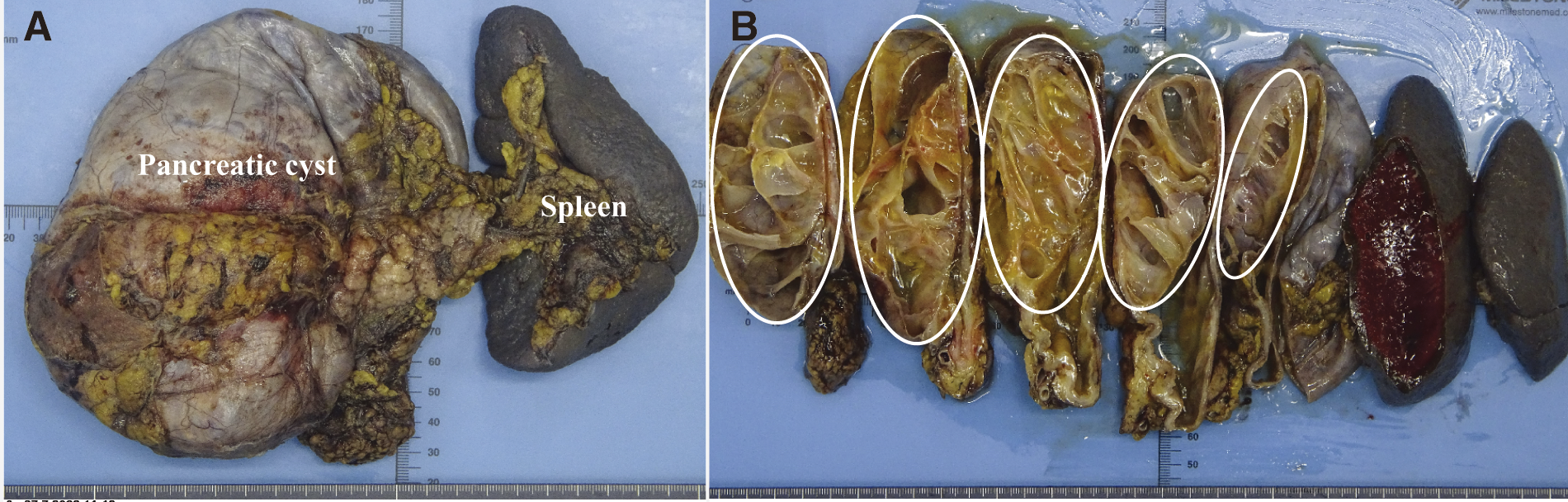

Fig. 5

The gross findings of the excised specimen: (A) Pancreas and spleen. (B) The specimens included the distal pancreas and spleen, with a 150 mm-sized cystic tumor with multifocal interiors (dotted line).

Pathological examination revealed a multifocal tumor continuous with the pancreatic parenchyma, showing mucous epithelium and progesterone receptor (PgR)-positive OTS. Papillary growth of p53-positive atypical columnar epithelium was noted on some cyst walls, but no evidence of stromal invasion or malignancy in the dissected lymph nodes was observed. Based on these findings, the tumor was diagnosed as a noninvasive mucinous cystadenocarcinoma (MCC) (Fig. 6). Surrounding the rupture site, the fibrous connective tissue layer was absent, and the cyst wall predominantly contained OTS components. The serosal side of the rupture exhibited strong inflammatory changes with desquamated epithelium and no malignant cells. Furthermore, BCL10 staining revealed many positive pancreatic acinar cells near the rupture site (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7

The findings at the site of the failed pancreatic cyst included a localized yellowish color change on the serosal side of the ruptured area (A, dotted line). Surrounding the ruptured site, the fibrous connective tissue layer was absent, and the cyst wall predominantly contained ovarian-type stroma components (B). The serosal side of the rupture exhibited strong inflammatory changes with desquamated epithelium and no malignant cells (C). BCL10 staining revealed many positive pancreatic acinar cells near the ruptured site (D, E). (A: gross findings, B: hematoxylin and eosin staining, 12.5×, C: hematoxylin and eosin staining, 100×, D: BCL10 staining, 12.5×, E: BCL10 staining, 200×).

In the postoperative course, the patient experienced a pancreatic fistula (ISGPF Grade BL, Clavien–Dindo Grade II) and was discharged on postoperative day 16. She is currently undergoing outpatient follow-up and remains alive and recurrence-free 1 year and 6 months after surgery.

DISCUSSION

MCNs are characterized by the presence of mucin-producing columnar epithelium and OTS.1) Moreover, MCN accounts for 1% of pancreatic tumors and predominantly affects women aged 40–60 years. Typically, MCN does not affect the pancreatic duct and is localized in the pancreatic body and tail.1) MCNs are classified according to the degree of dysplasia into mucinous cystadenoma, mucinous cystic tumors with moderate dysplasia, and noninvasive and invasive MCC.3) This progression underscores the importance of surgical resection to prevent carcinomatous transformation.4) Notably, MCC has been reported to have a better prognosis than does typical pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma5); however, invasive MCC has a poor prognosis and may cause peritoneal dissemination if cystic fluid leaks during manipulation.1)

The rarity of MCN rupture is attributed to its thick, fibrous capsules.2) Our literature review, involving cases reported on PubMed between 1986 and 2023 using three keywords, “mucinous cystic neoplasm,” “pancreas,” and “rupture,” identified 11 cases excluding our case6–16) (Table 1). All patients, including our case, were women with a median age of 33.5 (28–69) years. One case involved a pancreatic head treated with pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD), whereas others involving the pancreatic tail or body required DP. Seven patients were diagnosed with MCC, including ours. One of them was invasive, while the remaining six were noninvasive. The median follow-up duration was 20 (2–102) months. Two patients, including one with invasive MCC, experienced recurrence.9,16) The patient with invasive MCC received four courses of gemcitabine therapy after surgery because of the ruptured case of malignant tumor. However, re-operation was performed because of mechanical ileus by the local recurrence of the tumor 7 months after initial surgery; then she received additional gemcitabine therapy (a total of 16 courses).9) The other patient with noninvasive MCC was diagnosed with peritoneal dissemination 9 months after surgery. Gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel therapy were administered. The lesion had almost disappeared 12 months after surgery, then chemotherapy continued.16)

Table 1Reported cases of ruptured MCNs

| No. |

Author |

Year |

Age |

Sex |

Location |

Tumor

size

(mm) |

Surgical

procedure |

Diagnosis |

Pregnant |

Follow-up

(months) |

Recurrence |

Outcome |

| 1 |

Smithers6) |

1986 |

33 |

F |

Body/Tail |

100 |

DP |

MCC (noninvasive) |

Yes |

Unknown |

Unknown |

Unknown |

| 2 |

Ozden7) |

2007 |

32 |

F |

Tail |

150 |

SPDP |

MCC (noninvasive) |

Yes |

12 |

No |

Alive |

| 3 |

Bergenfeldt8) |

2007 |

42 |

F |

Body |

200 |

DP |

MCA |

No |

19 |

No |

Alive |

| 4 |

Naganuma9) |

2011 |

32 |

F |

Head |

110 |

PD |

MCC (invasive) |

Yes |

36 |

Local |

Alive |

| 5 |

Imoto10) |

2013 |

69 |

F |

Body/Tail |

60 |

DP |

MCC (noninvasive) |

No |

2 |

No |

Alive |

| 6 |

Haddad11) |

2019 |

30 |

F |

Tail |

150 |

DP |

MCA |

No |

36 |

No |

Alive |

| 7 |

Fujinaga12) |

2020 |

28 |

F |

Tail |

80 |

SPDP |

MCA |

No |

96 |

No |

Alive |

| 8 |

Revoredo13) |

2020 |

38 |

F |

Body/Tail |

200 |

DP |

MCA |

Yes |

96 |

No |

Alive |

| 9 |

Krishnamurthy14) |

2021 |

39 |

F |

Body/Tail |

92 |

DP |

MCA |

No |

6 |

No |

Alive |

| 10 |

Tezuka15) |

2022 |

28 |

F |

Tail |

90 |

DP |

MCC (noninvasive) |

No |

102 |

No |

Alive |

| 11 |

Oyama16) |

2023 |

53 |

F |

Tail |

75 |

DP |

MCC (noninvasive) |

No |

20 |

Peritoneal dissemination |

Alive |

| 12 |

Our case |

2023 |

34 |

F |

Tail |

150 |

DP |

MCC (noninvasive) |

No |

18 |

No |

Alive |

DP, distal pancreatectomy; MCA, mucinous cystadenoma; MCC, mucinous cystadenocarcinoma; MCN, mucinous cystic neoplasm; PD, pancreaticoduodenectomy; SPDP, spleen-preserving distal pancreatectomy

Four cases involved pregnant women.6,7,9,13) Regardless of the origin, this stroma is hormone-sensitive and regularly expresses PgRs.17) In other words, the development of MCN in women and the rapid growth of MCN during pregnancy indicate a significant role for sex hormones in MCN tumorigenesis.18)

No study has elucidated the cause of MCN rupture other than the involvement of sex hormones during pregnancy. We discuss the cause of MCN rupture in our case. Our case, as well as generally observed MCNs, had a robust fibrous capsule. Although the MCN was found to increase with time before the rupture, and the traction of the cyst wall is attributed to cyst growth, the robust fibrous capsule of the MCN makes it unlikely that this factor alone causes perforation. Furthermore, no history of trauma preceded the presentation of abdominal pain, ruling out external trauma as the cause. Additionally, cancer invasion was also excluded as no evidence of malignancy near the site of cyst rupture was observed. Under these circumstances, pathological examination revealed the disappearance of the fibrous connective tissue layer around the rupture site, accompanied by significant inflammatory changes on the serosal side. Therefore, we speculated that the cyst rupture in our case was caused by inflammatory changes in the cyst wall, leading to its weakening.

To further investigate the cause of these inflammatory changes, we performed a culture examination of the ascitic fluid and cyst contents, which ruled out bacterial or fungal infections as direct causes of inflammation. Additionally, BCL10 staining, specific to pancreatic acinar cells, was conducted,19) revealing a notable presence of positioned cells and conduits formed by these cells near the rupture site. This indicates that exocrine secretion, specifically pancreatic juice, was present.

Based on these findings, it might be possible that the rupture in our case was caused by a combination of cyst wall traction due to cyst growth and localized inflammatory changes. The inflammation might have resulted from the stasis of pancreatic fluid, leading to tissue fragility due to circulatory failure and localized pancreatitis. These findings contribute to our understanding of the mechanisms underlying ruptured MCN.

CONCLUSION

Ruptured MCNs are rare. In this study, we demonstrated for the first time that inflammation associated with pancreatic fluid stasis may be one of the causes of MCN rupture.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.jp) for English language editing.

DECLARATIONS

Funding

This study was not funded by any grant.

Authors’ contributions

Masataka Hirano drafted the manuscript.

Masanori Tsujie contributed to the data analysis and interpretation and assisted in the preparation of the manuscript.

All authors are accountable for all aspects of the work.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are not available for public access due to patient privacy concerns but are available on reasonable requests from the corresponding author, Masataka Hirano.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The publication of this case report was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee.

Consent for publication

The case report and publication process were explained to the patient, who granted permission to publish the report.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- 1) Yamao K, Yanagisawa A, Takahashi K, et al. Clinicopathological features and prognosis of mucinous cystic neoplasm with ovarian-type stroma: a multi-institutional study of the Japan pancreas society. Pancreas 2011; 40: 67–71.

- 2) Kimura W, Nomura T, Mizutani M, et al. Definition of MCN (mucinous cystic neoplasm of the pancreas) and a proposal for a new concept of MRN or MSN (mucinous round or spherical neoplasm). Hepatogastroenterology 2007; 54: 1954–6.

- 3) Reddy RP, Smyrk TC, Zapiach M, et al. Pancreatic mucinous cystic neoplasm defined by ovarian stroma: demographics, clinical features, and prevalence of cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004; 2: 1026–31.

- 4) Tanaka M, Fernández-del Castillo C, Adsay V, et al. International consensus guidelines 2012 for the management of IPMN and MCN of the pancreas. Pancreatology 2012; 12: 183–97.

- 5) Postlewait LM, Ethun CG, McInnis MR, et al. Association of preoperative risk factors with malignancy in pancreatic mucinous cystic neoplasms: a multicenter study. JAMA Surg 2017; 152: 19–25.

- 6) Smithers BM, Welch C, Goodall P. Cystadenocarcinoma of the pancreas presenting in pregnancy. Br J Surg 1986; 73: 591.

- 7) Ozden S, Haliloglu B, Ilter E, et al. An extremely rare cause of acute abdomen in pregnancy: ruptured pancreatic mucinous cystadenocarcinoma. Pancreas 2007; 34: 474–6.

- 8) Bergenfeldt M, Poulsen IM, Hendel HW, et al. Pancreatic ascites due to rupture of a mucinous cystic neoplasm. Acta Oncol 2008; 47: 978–81.

- 9) Naganuma S, Honda K, Noriki S, et al. Ruptured mucinous cystic neoplasm with an associated invasive carcinoma of pancreatic head in a pregnant woman: report of a case and review of literature. Pathol Int 2011; 61: 28–33.

- 10) Imoto A, Masuda D, Kurisu Y, et al. A case of mucinous cystadenocarcinoma of the pancreas with spontaneous rupture diagnosed by endoscopic retrograde pancreatography. Endoscopy 2013; 45(Suppl 2 UCTN): E36–7.

- 11) Haddad A, Sebai A, Rhaiem R, et al. Pancreatic mucinous cystadenoma doubly complicated by acute pancreatitis and retroperitoneal rupture. J Visc Surg 2019; 156: 72–4.

- 12) Fujinaga A, Hirashita T, Iwashita Y, et al. A case of ruptured mucinous cystadenoma of the pancreas with recurrence-free survival for 8 years. Surg Case Rep 2020; 6: 52.

- 13) Revoredo F, de Vinatea J, Reaño G, et al. Mucinous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas associated with pregnancy: Two case reports. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020; 99: e21471.

- 14) Krishnamurthy G, Ganesan S, Ramas J, et al. Ruptured mucinous cystadenoma pancreas: a case report and review of literature. Euroasian J Hepatogastroenterol 2021; 11: 45–8.

- 15) Tezuka S, Ueno M, Kobayashi S, et al. A case of pancreatic mucinous cystadenocarcinoma with malignant ascites without recurrence for more than 8 years after surgery. Clin J Gastroenterol 2022; 15: 834–9.

- 16) Oyama K, Iwagami Y, Kobayashi S, et al. A ruptured mucinous cystadenocarcinoma of the pancreas extensively evaluated before and after the rupture: a case report. Pancreas 2023; 52: e163–7.

- 17) Volkan Adsay N. Cystic lesions of the pancreas. Mod Pathol 2007; 20(Suppl 1): S71–93.

- 18) Ganepola GA, Gritsman AY, Asimakopulos N, et al. Are pancreatic tumors hormone dependent?: A case report of unusual, rapidly growing pancreatic tumor during pregnancy, its possible relationship to female sex hormones, and review of the literature. Am Surg 1999; 65: 105–11.

- 19) La Rosa S, Franzi F, Marchet S, et al. The monoclonal anti—BCL10 antibody (clone 331.1) is a sensitive and specific marker of pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma and pancreatic metaplasia. Virchows Arch 2009; 454: 133–42.

https://orcid.org/0009-0005-2542-5499

https://orcid.org/0009-0005-2542-5499