2021 年 129 巻 2 号 p. 223-232

2021 年 129 巻 2 号 p. 223-232

The Valley of the Nobles is a burial area that is located between the Valley of the Kings and the Valley of the Queens, together with which it constitutes the Theban Necropolis. The Valley of the Nobles houses the tombs of ancient aristocratic families, which include the monumental complex of the Neferhotep tomb, catalogued as TT49 (XVIIIth Dynasty). The funerary monument of Neferhotep also includes tombs TT187, TT347, TT348, TT362, and TT363, although tombs TT347, TT348 (Ramessid Period), and TT363 (XIXth Dynasty) remain closed. Tombs TT49, TT187, and TT362 contained numerous human remains in different states of conservation. Those in tomb TT187 were attributable to at least 71 individuals, who showed evident signs of combustion, and also taphonomic alterations that had occurred in recent decades. The context of tomb TT362 was different, as it contained animal and human mummified remains that were disarticulated and showed few signs of exposure to high temperatures. These remains were attributable to 64 individuals. Tomb TT49 contained the remains of a single individual inside the burial chamber. The taphonomic and anthropological data suggest that the tombs within the funerary complex of Neferhotep were frequented not only by modern populations, as they also testify to the ancient reuse of tombs in different phases from the Ramessid to Ptolemaic periods.

Since 2015, the Operative Unit of Anthropology of the ‘G. d’Annunzio’ University (Chieti, Italy) has been involved in a large multidisciplinary research project on the monumental complex of the Neferhotep tomb. This is catalogued in the abbreviated form with which the funerary monument of Neferhotep was named as TT49 (i.e. T[heban] T[omb No.] 49). This specific nomenclature was created and established by Gardiner and Weigall when they catalogued the Theban tombs in 1913 (Gardiner and Weigall, 1913).

The funerary monument of Neferhotep (Figure 1) is located in the Valley of Nobles in Luxor (i.e. ancient Thebes), on the eastern slope of the hill of el-Khokha (Pereyra et al., 2013). It is of particular interest in relation to the entire Theban necropolis because of its monumentality and the different phases of its use and reuse from the most ancient to modern times. Furthermore, its main tomb is one of the few Theban tombs dated to the reign of Pharaoh Ay (1333–1328 BCE), according to the remains of a cartouche in the vestibule of TT49 (Pereyra, 2006; Pereyra et al., 2013). The site is a multipart architectural and funeral complex that consists not only of a tomb with a single individual (TT49), but also of several tombs that belonged to some of the officials associated with Amun’s Temple. TT49 occupies a central position, with tombs TT187 and TT347 on its northern side, and tombs TT362, TT363, and TT348 built on its southern side (Pereyra et al., 2015). This group of tombs has been dated from the end of the XVIIIth Dynasty (14th–13th century BCE) to the Ramessid Period (17th–11th century BCE). This dating was based not only on archaeological records, such as the aforementioned cartouche, but also from the architectural type of the tomb. As Salima Ikram (2015) stated, rock-cut Theban tombs of the XVIIIth Dynasty were based on a T-shape, with the cross-bar running parallel to, and just behind, the cliff face. In the XIXth Dynasty, such tombs continued with this distinctive shape, with the existing elements modified. Then, in the Ramessid Period, it became common practice for tombs to descend in a spiral with undecorated corridors. These three phases are attested to in the Neferhotep complex; however, they show signs of use also during the late IIIrd Intermediate Period, before and after the Ptolemaic and Roman periods (Pereyra et al., 2015).

Map of the Valley of the Nobles and the Neferhotep complex.

The complexity of this site determined the choice of a multidisciplinary approach to delineate the complete picture of its history and the evolution of the monument, in both functional and symbolic terms (Lemos et al., 2017). Furthermore, the involvement of a large research team was fundamental for the reconstruction of the human processes that had affected the monumental complex through historical times. The aims of the Operative Unit of Anthropology were thus to excavate and study the biological remains from the funerary complex, and to analyse the taphonomic signs.

Together with tombs TT187, TT362, TT363, TT348, and TT347, the tomb of Neferhotep has undergone different phases of reuse over the centuries. The evidence of the long duration of the use and reuse of these tombs is also highlighted by stratigraphic, archaeological, and anthropological data that have been documented during the various excavation campaigns that have been conducted in previous years: Manzi and Cerezo (2009) provided useful data not only on their architectural development, but also on the daily life of the local communities, and especially in more recent times. In parallel with the expansion of the modern settlements on the hill of el-Khokhah, the tombs of the funerary complex of Neferhotep were often used as houses, warehouses, stalls, and cellars. The Hungarian archaeological mission in el-Khokha (TT184) (Németh, 2011; van der Spek, 2016) was the first to associate the modern upper stratigraphic layers in the Theban necropolis with full understanding of the taphonomic processes that had led to the formation of the final deposition context. Indeed, the tombs have continued to be used and reused both in ancient times for funerary purposes, and in modern times, thus creating a strong link between their present and their past.

The Theban necropolis was used by the local community until approximately the second decade of the 20th century, when the Supreme Service of Egyptian Antiquities carried out the final evictions of families and the demolition of most of the houses built on these ancient tombs (Simpson, 2003). According to the Supreme Service, the Karim Yusuf family used the funerary complex for habitation and stables from the end of the 19th century until 1913 (when the Supreme Service closed all of the Theban tombs) (Pereyra et al., 2015). From then until the end of the 1920s, the Karim Yusuf family limited their occupation to the courtyard of the complex. Unfortunately, the recent use of the tombs by modern populations has in some cases damaged the structures themselves, and has thus altered the archaeological and anthropological data. Indeed, it is not a coincidence that the ancient osteological materials found inside the tombs were not in their original positions, and were in many cases in a fragmented state of conservation.

The most significant case in terms of manipulation of ancient human remains in modern times was certainly the discovery of a large number of both mummified and skeletonized remains in the western pit in the vestibule of TT187. As demonstrated by the documentation available before 1929, the pit did not contain human remains, which were thus likely to have been deposited there by those who reused the tomb later on. It appears that the modern inhabitants decided to accumulate and burn the mummies in the tombs on one side to expand the space so that it could be used for another purpose, or maybe to eliminate the bad smell probably caused by the high concentration of the acid component of the organic products of the balms used in the mummification process, such as beeswax, Dead Sea bitumen, cedar oil, coniferous resins, gum, and many others (Colombini et al., 2000; Buckley and Evershed, 2001; Tchapla et al., 2004; Łucejko et al., 2017).

The tombs of the funerary complex of Neferhotep contained numerous disarticulated humans remains with taphonomic alterations of different natures. Here, we show the results of a taphonomic and anthropological analysis of the human remain from tombs TT187, TT362, and TT49, which are part of the funerary monument.

The materials consist of the disarticulated skeletal and mummified remains that were recovered from tombs TT187, TT362, and TT49 of the Neferhotep funerary complex. The morphological and metric analyses were carried out in the field, because it was not possible to move the human remains from the archaeological site.

The minimum number of individuals was estimated by counting the mandibles, clavicles, scapulae, humeri, radii, ulnae, hemi-hip bones, femurs, patellae, tibiae, astragals, and calcanei, following the recommendations of Buikstra and Ubelaker (1994). Estimations were made of the sex when possible, according to the secondary sexual characteristics of the skull and pelvis (Ferembach et al., 1979), or following the method of Alemàn Aguilera et al. (1997) in terms of the other postcranial skeletal elements (i.e. clavicle, scapula, humerus, ulna, radius, femur, patella, tibia, fibula, talus, calcaneus). Age at death was estimated from the degree of resorption of the cranial sutures, as proposed by Meindl and Lovejoy (1985), from the morphological changes of the pubic symphysis, according to the standard proposed by Brooks and Suchey (1990), and from dental wear (Brothwell, 1981; Lovejoy, 1985). The age at death of young individuals was estimated on the basis of the lengths of the long-bone shaft and ilium, and teeth development and eruption, according to the indications of Scheuer and Black (2000).

Following the Vallois method (1960), the individuals were divided into the following age groups: infants I, 0–6 years; infants II, 7–12 years; juveniles, 13–20 years; young adults, 21–40 years; mature adults, 41–60 years; and senile adults, 61+ years. Estimation of stature was based on the maximum length of the long bones when possible, according to the Trotter and Gleser formulae (1952), or by measurements of the fragments, following methods described by Steele and McKern (1969).

The taphonomic alterations caused by heat and the estimation of the temperatures to which the human remains were exposed were carried out following the indications of Schmidt et al. (2015).

Excavations at the funerary complex of Neferhotep revealed an archaeological stratigraphy that represented more than a single phase of use of the tombs (Lemos et al., 2017). The main tomb, TT49, and tombs TT187 and TT362, were used and reused until the IIIrd Intermediate Period. This complex appears to have then been abandoned at the beginning of the 19th century, when people entered the tombs and partially destroyed them, creating a new (and the last) phase of reuse (Pereyra et al., 2015).

According to the inscriptions on the tomb walls, the main owners of TT187, TT362, and TT49 were Pakhyhat, Paanemwaset, and Neferhotep, respectively. However, the funerary complex provided numerous disarticulated humans remains in different states of preservation that were heterogeneously distributed in the different areas of the tombs. This thus confirms the use of the funerary complex through different periods and for a long time (Manzi and Cerezo, 2009; Lemos et al., 2017).

According to the analyses of Pereyra et al. (2015) and Lemos et al. (2017), TT187 had at least three phases of use: the first in ancient times, the second immediately afterwards, for further burials, and the last in modern times, as housing. The architecture of the tomb indicated a XIXth Dynasty date. However, the inscription ‘Pakhihat, wab-priest of Amun’ at the entrance was written over older inscriptions (Davies, 1933). This indicates the Pakhihat burial, which has been dated to the XXth Dynasty (Kampp, 1996), was the first reuse of the tomb, when the original name of the owner was lost. The reuse of the tomb might be related to social ties of the living with previous people and family who held the same specific position within a significant social network (Lemos et al., 2017), such as the wab-priests of Amun, which might have allowed them to usurp and share the scheme decoration (Ikram, 2015).

The anthropological excavation of TT187 uncovered isolated and disarticulated human remains and circumscribed body parts that were still in anatomical connection. Among the human findings, there are also some complete skulls, arms, and legs that were still wrapped in bandages. The ancient detachment of rock fragments from the walls and the vault of the tomb certainly damaged the human remains; however, the alterations to the sepulchral context were most likely to have been carried out in modern times. This is demonstrated in particular by the apparent out-of-context presence of two completely burned human bodies that appear to have been abandoned on the floor at the entrance to the tomb. When Norman De Garis Davies (1933) visited the tomb in 1927–1929, no mention was made of any human remains in the two pits in the antechamber, although it was noted that there were people living inside the tomb. Therefore, we can deduce that only after 1929 was the tomb used for habitation, or as a stable and/or storage site. In this third phase of reuse, the inhabitants appear to have removed the mummies to store them in a single area, to create more space, and the mummies remains were most likely burned to reduce their volume and to eliminate the bad smell.

The human remains from TT187 were mainly in the western pit of the antechamber, and secondarily in the funerary chamber, with only a few elements mixed with debris scattered alongside the shaft. Usually, in a T-shaped tomb, people were buried only in the funerary chamber, and if necessary, in the shaft.

Most of the bones in TT187 showed clear changes in shape and size that were caused by exposure to temperatures of up to 800–900°C, as judged by the bluish-white colour of some of the calcined bones, and by the fracturing and warping of the bone elements (Bontrager and Nawrocki, 2015; Devlin and Herrmann, 2015) (Figure 2). The colour and distribution of the burns on the bone surfaces were irregular in some cases, with areas of different colours separated by clear dividing lines (Figure 3A). This distribution pattern of the burned areas suggests that the heat acted directionally, and involved the amassed bodies. Thus, the outer bodies shielded the underlying bones by interposing between the heat source and the bones underneath (Schmidt et al., 2015). The diploe and the inner table of the cranial bones showed different chromatic alterations with respect to these observables on the outer layer of the cortical bone, as the spongiosa was protected by the external compact bone, which reduced its heat exposure (Symes et al., 2015) (Figure 3B). Conchoidal fractures were visible on the diaphysis of numerous long bones, which indicated the presence of soft tissues at the time of the combustion (Symes et al., 2015). The heat-related changes on the convex and spherical bone surfaces, such as the heads of humeri and femurs, and the flat bones of the cranial vault were in the form of dense mosaics of small polygonal fractures of the bone surface (Reverte Coma, 1996). The teeth also showed morphological alterations and injuries caused by high temperatures. In some cases, the enamel coating was partially detached to expose the dentine below, which is a phenomenon that is known to occur at temperatures of 500–700°C (Sandholzer, 2015) (Figure 4). The pit and the shaft of the tomb were successively covered with sand, chaff, and dirt to isolate the human remains from the inhabited spaces.

Distribution of the human remains of TT187 based on the different heat exposures.

Skull fragment from TT187, with a directional burn (A) and different chromatic alterations (B).

Mandible from TT187, with heat alterations to the teeth (arrows).

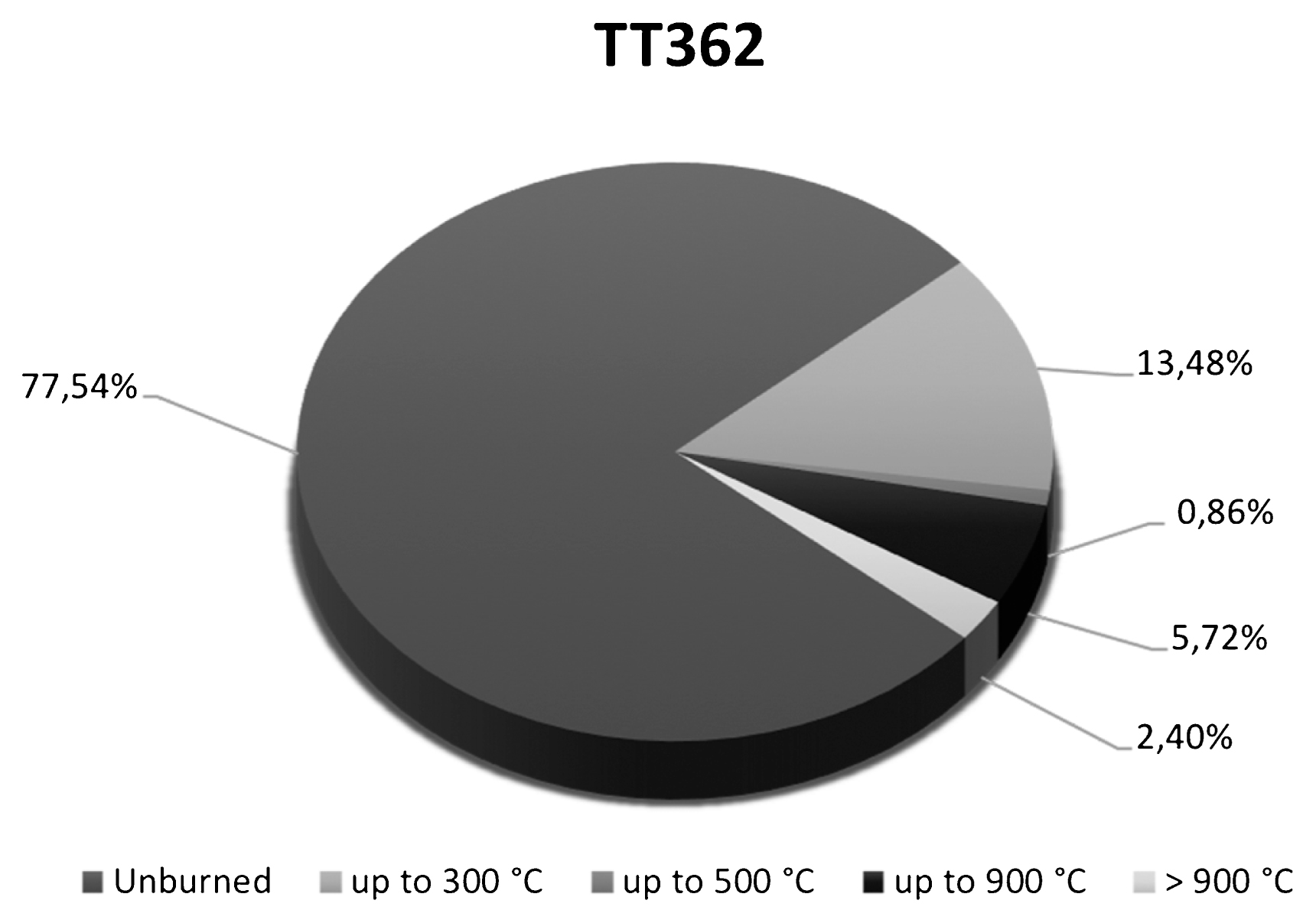

Unlike tomb T187, tomb TT362 mainly contained mummified and disarticulated human and animal remains and bones, with only a few alterations due to exposure to high temperatures (Figure 5). The tomb revealed different phases of reuse too. According to its initial architectural design, TT362 would appear to be attributable to the Ramessid period (12th–11th century BCE), as confirmed by the decorative apparatus (Pereyra et al., 2015). The construction of the western funerary pit in the antechamber dates back to the second phase, which the archaeological findings (i.e. shabty, cartonnage, pottery) place between the end of the IIIrd Intermediate Period (10th–7th century BCE) and the beginning of the Late Period (7th–4th century BCE). In the third, and last, ancient phase of reuse, there was an extension of the burial chamber, which included the burial chamber of a neighbouring tomb, and all of the burials (dated to the Ptolemaic period, according to the inscriptions on bandages) were mixed and put back together (Pereyra et al., 2015).

Distribution of the human remains of TT362 based on the different heat exposures.

The obstruction of the shaft leading to the burial chamber by disarticulated human remains demonstrated the major disturbance of the original funerary context in modern times. Modern inhabitants used to live and raise cattle in this structure, as indicated by the presence in the site of various modern objects.

Despite the great level of disturbance, the state of conservation of the bones and mummified remains was good. These remains were not only in the dromos and the funerary chamber, as expected for a T-shaped tomb; most of them were in the western pit of the antechamber. Unlike TT187, there were no traces of burning on these remains in the western pit, probably because this is deeper and wider than that in TT187, and so the modern inhabitants just covered them up with sand and chaff. The bandages with different weaving testify to the presence of individuals who belonged to different periods, and to the work of different embalmers (Figure 6). The embalming procedure involved the application of abundant layers of resin to bodies, which were still visible on these remains (Figure 7). Together with the human remains, other mummified remains of an unspecified nature were found, which appeared to be textiles wrapped around themselves and soaked in balsams. These textile findings had variable lengths (11–18 cm), and relatively constant width and thickness, about 5 and 3 cm, respectively; however, these appear to be incomplete parts of larger exhibits (Figure 8). These samples might have been connected with the viscera, which instead of being placed in canopic jars, were returned to the body in separately wrapped packages after desiccation, and were wrapped up with the rest of the body. This was a procedure typical of the IIIrd Intermediate Period (Ikram, 2015). This tomb also contained partial remains of animals of various species, some of which were mummified and still blindfolded, others of which were completely skeletonized and with signs of slaughter; these latter would appear to be of a more recent age.

Bandages with different weaving.

Vitrified resin from the back of a mummy.

Little packages of textiles, balsams, and human remains.

In both TT187 and TT362, the funerary chambers and the dromos were not used as living spaces by the modern population, but for refuse disposal and as an area where the human remains were accumulated, to save space in the front rooms. As van der Spek (2011) stated, this might be because the funerary chambers were considered locally as ‘contaminated’ by the ancient mummies and bodies, and consequently later inhabitants were afraid of ancient spirits. Furthermore, the holes at the entrance of the corridor leading to the funerary chambers might have served as the delimitation of the space for living, as opposed to the ‘funerary areas’ (Lemos et al., 2017).

The main tomb of the complex, TT49, had a similar ancient history of reuse, but a different use in modern times. The first owner was the scribe Neferhotep, son of Neby, whose titles, according to the inscriptions (Lemos et al., 2017), included ‘great of Amun,’ ‘overseer of the oxen and heifers,’ and ‘overseer of weavers of Amun.’ This first phase of use is dated from the end of the XVIIIth Dynasty to the Ramessid Period (14th–13th century BCE).

TT49 had a T-shaped monumental architecture, as it had the largest antechamber, followed by the only hypostyle hall of the complex. The first reuse of the tomb can be dated to probably a time shortly after the original period of its use. As the house of worship and the existing iconography were respected, the two subsequent occupants might have been relatives or descendants. The second phase of reuse was defined as the ‘Usurper phase’ (Pereyra et al., 2013). The new funerary chamber that the usurper built under the north side of the main room of the tomb contained human remains that are attributable to a single individual.

In 1828–1829, Champollion reported in his Notice Descriptives that the tomb was in a state of almost complete destruction, and that the three rooms of the tomb were full of mummies burned by a fire that broke out in the monument (Pereyra et al., 2015). When the expedition of the Metropolitan Museum of New York arrived at the necropolis around 1920 (Davies, 1933), the situation was once again different. In the 20th-century phase, the tomb of Neferhotep was used as a house and stables by the Karim Yusuf family, and there was no mention of the presence of burned remains, which had probably been moved to the other tombs and further reduced to provide more space. Indeed, the few human remains were only in the Usurper’s funerary chambers, while the main shaft and burial chambers were empty.

The taphonomic data of the Neferhotep complex confirm therefore the frequentation of the tombs by local populations in ancient and modern times. This continuous use and reuse of tombs makes it difficult, if not impossible, to establish the correct positions of the human remains inside the different tombs. However, anthropological analysis allows us to reconstruct the composition of the people who were found buried inside the Neferhotep complex.

AnthropologyThe anthropological analysis was made difficult by the numerous reuses of the tombs and the displacement of the mummies, not only from their original positions, but probably also among the tombs. However, anthropological analysis allowed us to reconstruct the composition of the people who were buried inside the Neferhotep funerary complex.

As defined according to the analysis of the data given in Table 1 and Table 2, the minimum number of individuals inside the Neferhotep funerary complex was 135 individuals: 1 fetus/perinatal; 7 infants I; 6 infants II; 9 juveniles; 4 indeterminate subadults; 8 young adults; 8 mature adults; 0 senile adults; and 92 indeterminate adults. There are at least 20 females, 22 males, and 93 individuals of indeterminate sex.

| Anatomical region | Detail | Number of samples for each age class (n) | Total | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fetus | Infant | Juvenile | Indeterminate subadult | Adult | |||||||||||||||||

| I | II | Young | Mature | Older | Indeterminate | ||||||||||||||||

| (0–6 y) | (7–12 y) | (13–20 y) | (0–20 y) | (21–40 y) | (41–60 y) | (61+ y) | (21+ y) | ||||||||||||||

| R | L | R | L | R | L | R | L | R | L | R | L | R | L | R | L | R | L | R | L | ||

| Skull | Cranium | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 27 | 29 | ||||||||||

| Mandible | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | |

| Axis | Complete | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||

| Clavicle | 1/3 sternal | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 4 |

| 1/3 acromial | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | |

| Scapula | Complete | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 5 | 10 | 7 |

| Humerus | 1/3 proximal | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 24 | 21 | 29 |

| 1/3 distal | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 35 | 21 | 36 | |

| Ulna | 1/3 proximal | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 5 | 11 | 5 |

| 1/3 distal | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 1 | |

| Radius | 1/3 proximal | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 6 | 10 | 6 |

| 1/3 distal | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 1 | |

| Coxa | Ilium | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 21 | 30 | 29 | 35 |

| Ischium | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 30 | 27 | 35 | |

| Pubis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 30 | 27 | 40 | |

| Femur | 1/3 proximal | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 52 | 47 | 59 | 51 |

| 1/3 distal | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 48 | 49 | 52 | 51 | |

| Patella | Complete | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 6 |

| Tibia | 1/3 proximal | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 9 | 13 | 12 |

| 1/3 distal | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 9 | 7 | 10 | |

| Fibula | 1/3 proximal | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| 1/3 distal | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 9 | 7 | 9 | |

| Talus | Complete | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| Calcaneus | Complete | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

R, right side; L, left side.

Data in bold indicate the minimum number of individuals for each age class.

| Anatomical region | Detail | Number of samples for each age class (n) | Total | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fetus | Infant | Juvenile | Indeterminate subadult | Adult | |||||||||||||||||

| I | II | Young | Mature | Older | Indeterminate | ||||||||||||||||

| (0–6 y) | (7–12 y) | (13–20 y) | (0–20 y) | (21–40 y) | (41–60 y) | (61+ y) | (21+ y) | ||||||||||||||

| R | L | R | L | R | L | R | L | R | L | R | L | R | L | R | L | R | L | R | L | ||

| Skull | Cranium | 0 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 22 | 40 | ||||||||||

| Mandible | 0 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 6 | 21 | 15 | |

| Axis | Complete | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 6 | ||||||||||

| Clavicle | 1/3 sternal | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 9 | 8 | 11 |

| 1/3 acromial | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 8 | |

| Scapula | Complete | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 7 | 7 | 8 |

| Humerus | 1/3 proximal | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 27 | 22 | 31 | 24 |

| 1/3 distal | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 37 | 44 | 39 | |

| Ulna | 1/3 proximal | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 23 | 18 | 27 | 20 |

| 1/3 distal | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 8 | 10 | 9 | |

| Radius | 1/3 proximal | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 15 | 15 | 15 |

| 1/3 distal | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 12 | 14 | 13 | |

| Coxa | Ilium | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 19 | 23 | 33 |

| Ischium | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 19 | 20 | 30 | |

| Pubis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 18 | 20 | 30 | |

| Femur | 1/3 proximal | 0 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 22 | 29 | 28 | 34 |

| 1/3 distal | 0 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 22 | 25 | 28 | 29 | |

| Patella | Complete | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Tibia | 1/3 proximal | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 5 | 20 | 5 |

| 1/3 distal | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 5 | 13 | 5 | |

| Fibula | 1/3 proximal | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 1 |

| 1/3 distal | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | |

| Talus | Complete | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 9 | 11 | 9 |

| Calcaneus | Complete | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 7 | 14 | 7 |

R. right side; L, left side.

Data in bold indicate the minimum number of individuals for each age class.

Tomb TT187 contained human remains that were attributable to a minimum of 71 individuals: 59 adults and 12 subadults (Table 1). Tomb TT362 contained a minimum of 64 individuals: 49 adults and 15 subadults (Table 2). The combined data for the two tombs show that the proportion of subadults (27/135; 20.0%) was lower than that for the adults (108/135; 80.0%). Starting from the assumption that the tombs were destined for deaths in families belonging to the middle–upper social classes who would have had good financial resources and access to the medical care of the time, it is surprising to find a relatively high number of young individuals, at 20% of the sample. For Roman Egyptians, mortality rates were high in the first year of life (23–33%), but then greatly decreased between 5 and 15 years of age (to ~6%) (Zakrzewski, 2015). Many authors (Brass, 1975; Buikstra et al., 1986; Horowitz et al., 1988; Chamberlain, 2009) have stated that a high ratio between the number of subadult and adult deaths (also known as the Juvenile Index) can be interpreted as an indirect hint of elevated fertility levels.

Because these human remains were disjointed and artificially collected in circumscribed areas within the tombs, it was not possible to establish whether there was, or had been, a differentiation in the distribution and arrangement or orientation of the male and female bodies. Furthermore, it was possible to estimate the sex and age classes of relatively few of these individuals, because of their bad preservation and the destruction of the remains by fire. However, the presence of individuals of different ages suggests that there was no selection in terms of sex and age of the individuals buried within the Neferhotep complex.

Table 3 shows the male/female ratios for the individuals defined for tombs TT187 and TT362. There were about the same number of male and female adults estimated, although most of the individuals remained of indeterminate sex.

| Anatomical region | Sex | Tomb 187 | Tomb 362 | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n) | (%) | Ratio | (n) | (%) | Ratio | (n) | (%) | Ratio | ||

| Cranium | M | 11 | 40.7 | 1:1 | 11 | 37.9 | 1.2:1 | 22 | 39.3 | 1:0.9 |

| F | 11 | 40.7 | 9 | 31.0 | 20 | 35.7 | ||||

| Ind | 5 | 18.5 | 9 | 31.0 | 14 | 25.0 | ||||

| Mandible | M | 1 | 100.0 | — | 7 | 58.3 | 1:0.1 | 8 | 61.5 | 1:0.1 |

| F | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 8.3 | 1 | 7.7 | ||||

| Ind | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 33.3 | 4 | 30.8 | ||||

| Clavicle | M | 1 | 25.0 | — | 3 | 33.3 | — | 4 | 30.7 | — |

| F | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | ||||

| Ind | 3 | 75.0 | 6 | 66.7 | 9 | 69.2 | ||||

| Scapula | M | 2 | 25.0 | — | 1 | 14.3 | 1:1 | 3 | 20.0 | 1:0.3 |

| F | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 14.3 | 1 | 6.7 | ||||

| Ind | 6 | 75.0 | 5 | 71.4 | 11 | 73.3 | ||||

| Humerus | M | 2 | 5.7 | 1:2 | 8 | 20.0 | 1:0.3 | 10 | 13.3 | 1:0.6 |

| F | 4 | 11.4 | 2 | 5.0 | 6 | 8.0 | ||||

| Ind | 29 | 82.9 | 30 | 75.0 | 59 | 78.7 | ||||

| Ulna | M | 3 | 30.0 | — | 0 | 0.0 | — | 3 | 8.8 | — |

| F | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | ||||

| Ind | 7 | 70.0 | 24 | 100.0 | 31 | 91.2 | ||||

| Radius | M | 5 | 62.5 | — | 2 | 13.3 | 1:1 | 7 | 30.4 | 1:0.3 |

| F | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 13.3 | 2 | 8.7 | ||||

| Ind | 3 | 37.5 | 11 | 73.3 | 14 | 60.7 | ||||

| Coxa | M | 4 | 12.5 | 1:2 | 12 | 57.1 | 1:0.8 | 16 | 30.2 | 0.9:1 |

| F | 8 | 25.0 | 9 | 42.9 | 17 | 32.1 | ||||

| Ind | 20 | 62.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 20 | 37.7 | ||||

| Femur | M | 4 | 7.7 | 1:2 | 7 | 24.1 | 0.9:1 | 11 | 13.6 | 0.7:1 |

| F | 8 | 15.4 | 8 | 27.6 | 16 | 19.8 | ||||

| Ind | 40 | 76.9 | 14 | 48.3 | 54 | 66.7 | ||||

| Patella | M | 1 | 20.0 | 1:1 | 0 | 0.,0 | — | 1 | 10.0 | 1:1 |

| F | 1 | 20.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 10.0 | ||||

| Ind | 3 | 60.0 | 5 | 100.0 | 8 | 80.0 | ||||

| Tibia | M | 2 | 16.7 | — | 0 | 0.0 | — | 2 | 6.9 | 0.5:1 |

| F | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 23.5 | 4 | 13.8 | ||||

| Ind | 10 | 83.3 | 13 | 76.5 | 23 | 79.3 | ||||

| Fibula | M | 2 | 22.2 | 2:1 | 3 | 60.0 | 1:0.7 | 5 | 35.7 | 1:0.6 |

| F | 1 | 11.1 | 2 | 40.0 | 3 | 21.4 | ||||

| Ind | 6 | 6.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 42.9 | ||||

| Talus | M | 0 | 0.0 | — | 6 | 54.5 | 1:0.5 | 6 | 33.3 | 1:0.7 |

| F | 1 | 14.3 | 3 | 27.3 | 4 | 22.2 | ||||

| Ind | 6 | 85.7 | 2 | 18.2 | 8 | 44.4 | ||||

| Calcaneus | M | 2 | 33.3 | — | 5 | 35.7 | 1:0.4 | 7 | 35.0 | 1:0.3 |

| F | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 14.3 | 2 | 10.0 | ||||

| Ind | 4 | 66.7 | 7 | 50.0 | 11 | 55.0 | ||||

M, male; F, female; Ind, indeterminate.

The mean height of the male adults would have been 168.5 cm (range, 165–172 cm), while that of the female adults would have been 154.5 cm (range, 153–156 cm). The male individuals were therefore 14 cm taller than the female individuals on average. In comparison with modern Egyptians (El-Zanaty and Way, 2009; Subramanian et al., 2011), the average male height is the same as for the individuals from the present study, while the ancient females would have been ~4 cm shorter than the modern females.

Tomb TT49 included human remains attributable to a single individual in the Usurper funerary chamber. These consisted of a partially mummified head that was probably of an adult female (Figure 9). The head was well preserved, with the soft tissues of the face and upper neck region completely mummified, and some strips of bandages still attached to the right temporal–parietal region. The scalp had long strands of hair gathered in locks, which were perfectly preserved. The hair started from the forehead and reached the occipital region by brushing the base of the neck. The parietal bone and right temporal bone were partially skeletonized. On the upper region of the cranial vault, near the bregma, there was an osteolytic lesion that extended for ~3 cm anteroposteriorly, and for ~5 cm in the direction of the right ear. The preliminary macroscopic analyses carried out at the site indicated that the lesion occurred postmortem. Palaeopathological studies are in progress.

Skull of the individual from TT49, showing the right and left sides.

The excavation and analysis of the funerary complex of Neferhotep showed different taphonomic contexts that linked the original use and different reuses of these tombs. In ancient times the tombs were used by different Dynasties, from the Ramessid up to the Ptolemaic periods. This reuse might suggest a relationship of descendance among the families concerned. However, they might also be tied socially through the same profession (in this case, ‘wab priests of Amun’), thus sharing the same inscription. In modern times, the use of the tombs as houses was linked to the development of Qurna village on el-Khokha Hill in the 19th century. Although the modern inhabitants will have had no emotional connection with these tombs, they respected, and probably feared, the people buried inside, and they did not occupy the areas where the mummies were originally placed, or were later collected.

This use of the tombs was probably the cause of the present-day discovery of exclusively human remains that were disarticulated and distributed in the various areas of the tombs, without any apparent order. The human remains from TT187 consisted of bones that mainly had burn marks. Tomb TT362 contained partially or completely mummified human remains, which showed only a few alterations from exposure to high temperatures.

The anthropological data determined the presence of a great number of individuals buried inside these tombs, who will have belonged to different and diachronic groups. Because both male and female individuals of different ages were found (from birth to the older adult ages), it is reasonable to conclude that these ancient Egyptian tombs will have been used for all of the family members, with no selection by sex or age.