2021 年 3 巻 11 号 p. 639-646

2021 年 3 巻 11 号 p. 639-646

Background: Kurort is a German term from the words kur (cure) and ort (area), and refers to improvements in patients’ health in areas full of nature. We investigated the effect of kurort health walking in the 2 urban-style kurort health walking courses opened in Gifu City on systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), heart rate, and mood.

Methods and Results: The subjects were 454 people (136 males, 318 females; mean [±SD] age 61.7±9.9 years) taking part in kurort health walking for the first time. SBP, DBP, and heart rate were measured before and after kurort health walking. Mood was assessed using a 10-item checklist after kurort health walking. Kurort health walking significantly decreased SBP and DBP and increased heart rate. The decrease in SBP was significantly greater in the SBP ≥140 than <140 mmHg group, indicating that SBP before Kurort health walking was inversely correlated with the change in SBP. Similarly, the decrease in DBP was significantly greater in the DBP ≥90 than <90 mmHg group, indicating that DBP before kurort health walking was also inversely correlated with the change in DBP. All 10 items on the mood assessment were significantly improved after kurort health walking.

Conclusions: Kurort health walking preferentially decreases higher blood pressure and improves mood.

Hypertension and mental health status (e.g., depression) have been reported to be associated with cardiovascular events.1–3 Therefore, it is important to control blood pressure and to maintain a healthy mental state to reduce the risk of cardiovascular events. Although antihypertensive drugs and antidepressants are useful in preventing hypertension and depression, respectively, some lifestyle modifications may also be effective. Kurort is a German term from the words kur (cure) and ort (area) and refers to improvements in patients’ health in areas rich in nature, such as scenic hills, forests, rivers, hot springs, and areas with a good climate.4 In Japan, Japanese-style kurort, based on the German kurort, has recently been developed and has become popular with the support of local governments and companies. Kurort health walking describes walking in a healthy area called kurort. On October 26, 2019, Gifu City opened 2 urban-style kurort health walking courses, the Mt. Kinka-Nagara River-Gifu Park course and the Mt. Dodogamine-Nagara River-Fureai Forest course, and has been encouraging citizens to participate in kurort health walking. These 2 courses are easily accessible to citizens. Because these 2 kurort health walking courses are rich in nature, well designed, and well maintained, walking such courses may have a good effect on physical and mental health, which are related to cardiovascular disease.

The aim of the present study was to investigate the effects of kurort health walking in the kurort health walking courses in Gifu City on systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), heart rate, and mood.

Participants in the kurort health walking program obtained information regarding the places, dates, and times for kurort health walking through the public relations magazines of Gifu City. The subjects in this study were 454 first-time kurort health walking participants who used either of the 2 kurort walking courses in Gifu City between June 1, 2020 and May 30, 2021.

Because some people undertook kurort health walking several times, the total cumulative number of participants in the program was 893; however, only those people walking the course for the first time were enrolled in the present study. All participants agreed to take part in the study and provided written informed consent before the study commenced. No one dropped out during the study.

Participants were asked to provide details regarding their age, sex, height, weight, presence of hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes on a checklist before walking. SBP, DBP, and heart rate were measured using a wrist-type automatic sphygmomanometer, which is easy to use outdoors, before and after kurort health walking. After walking, participants were asked to complete a survey to evaluate changes in mood.

To ensure safety, participants with an SBP >180 mmHg and/or a DBP >110 mmHg are prohibited from kurort health walking, and kurort health walking is not performed in July and August because of the very hot climate in Gifu City in summer. Warming-up exercise before walking and cooling-down exercises after walking were performed under the direction of the health exercise instructors.

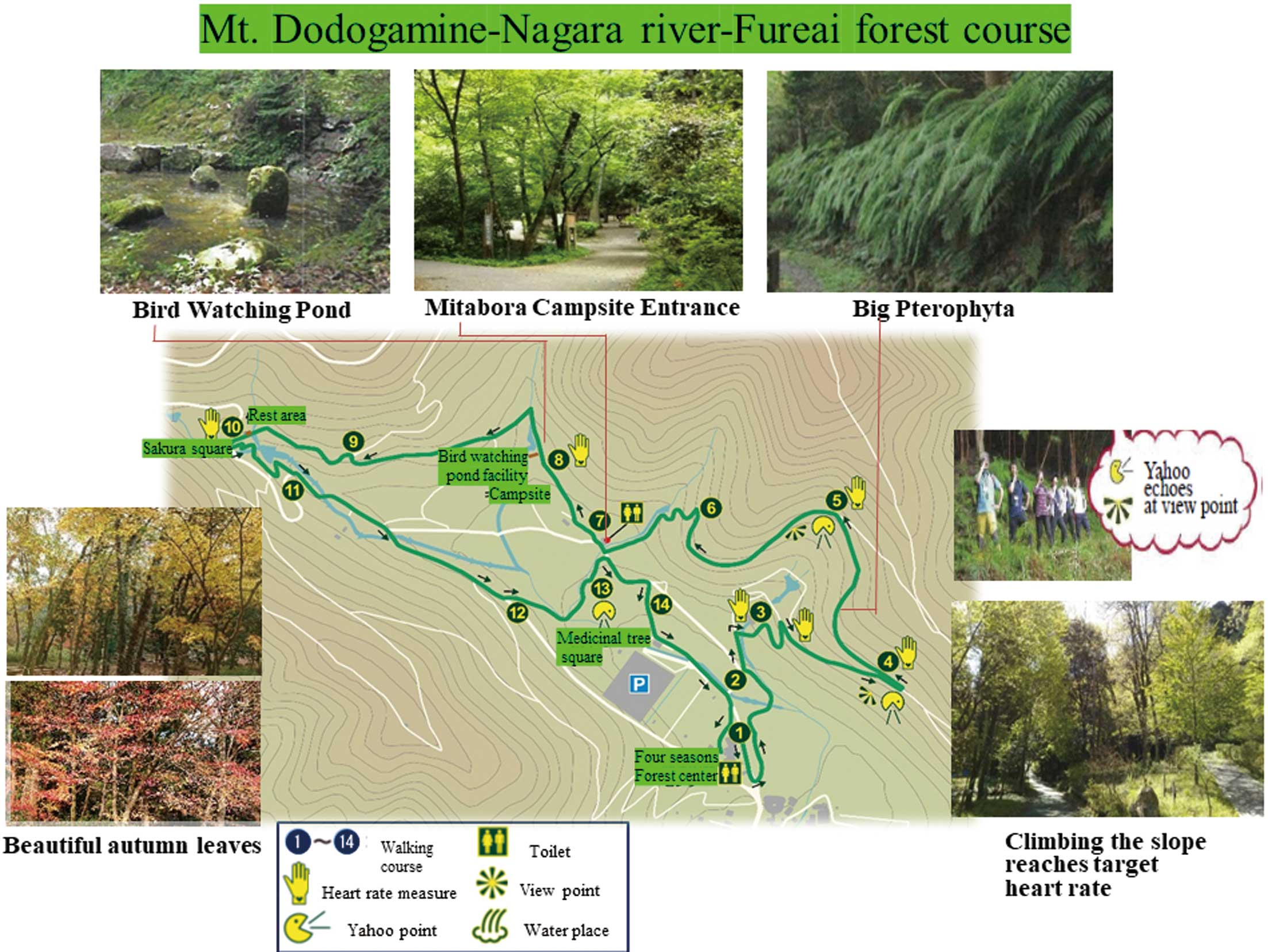

There are 2 courses for kurort health walking in Gifu City. The Mt. Kinka-Nagara River-Gifu Park course (Figure 1) is situated in the city center close to the Nagara River and extends to the foot of Mt. Kinka. This course is 2.3 km long and has an elevation of 30 m. The Mt. Dodogamine-Nagara River-Fureai Forest course (Figure 2) is situated in the northern area of the city and consists of a beautiful forest with many seasonal birds. This course is 3.2 km long and has an elevation of 80 m.

Mt. Kinka-Nagara River-Gifu Park course. This course is situated in the city center close to the Nagara River and extends to the foot of Mt. Kinka. This course is 2.3 km long and has an elevation of 30 m.

Mt. Dodogamine-Nagara River-Fureai Forest course. This course is situated in the northern area of the city in a beautiful forest with many seasonal birds. This course is 3.2 km long and has an elevation of 80 m.

To maintain target heart rate during walking, participants were asked to measure their heart rate at 5 points on the Mt. Kinka-Nagara River-Gifu Park course, and on 6 points on the Mt. Dodogamine-Nagara River-Fureai Forest course (Figures 1,2). Participants walked either course, accompanied by 2 health exercise instructors. The target heart rate during walking was defined as (160−age) beats/min. If the heart rate increased beyond the target heart rate, participants were asked to slow the pace of walking so that heart rate was maintained under the target. Because the exercise level was maintained under the anaerobic threshold, it was considered safe for cardiac patients.5

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Gifu Municipal Hospital (Approval no. 634) and conformed with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki (Br Med J 1964; ii: 177). This study was registered with the University Hospital Medical Information Network (UMIN) Clinical Trials Registry (ID: UMIN000041617).

Measurement of SBP, DBP, and Heart RateSBP, DBP, and heart rate were measured before and after the completion of kurort health walking using a wrist-type sphygmomanometer. In analyses, SBP and DBP were each divided into 2 groups (SBP ≥140 and <140 mmHg; DBP ≥90 and <90 mmHg group) based on the definition of hypertension in the 2019 Japanese Society of Hypertension guidelines for the management of hypertension.6

Heart rate was only evaluated for the 403 participants who documented their heart rate both before and after kurort health walking in the checklist.

Measurement of MoodBased on a previously reported method,7 a questionnaire was used in this study to determine changes in the following 10 mood items: feeling lively, feeling refreshed, a vivid feeling, feeling exhilarated, feeling relaxed, feeling calm, a fun feeling, feeling anxious, feeling irritated, and feeling tired after completing the kurort health walking. Participants rated each item as ‘improved’, ‘no change’, or ‘worsened’. These ratings were scored as 1 for ‘improved’, 0 for ‘no change’, and −1 for ‘worsened’. The effects of kurort health walking on each of the 10 mood items individually and the sum score for all 10 mood items were assessed by averaging scores across all 454 participants.

Statistical AnalysisData are presented as the mean±SD. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to determine the normality of data distribution. The significance of the differences in variables between groups was determined by paired and unpaired Student’s t-tests. Correlation coefficients between 2 variables were obtained by linear regression analysis. Two-sided P<0.05 was considered significant, and P<0.01 and P<0.001 were considered highly significant. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 7 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

Of the 454 participants in this study, 136 were male and 318 were female. The age of participants ranged from 11 to 89 years (mean age 61.7±9.9 years). Mean body mass index was 22.1±2.8 kg/m2. Some of participants (~30%) had past histories of hypertension (n=84), diabetes (n=22), and dyslipidemia (n=31).

SBP, DBP, and Heart RateKurort health walking significantly decreased both SBP (from 130.5±18.4 to 124.4±16.8 mmHg; P<0.0001; n=454; Figure 3A) and DBP (from 81.6±11.3 to 80.6±11.8 mmHg; P=0.0203; n=454; Figure 3B). Heart rate increased significantly from 73.1±12.1 to 75.8±12.3 beats/min (P<0.0001; n=415; Figure 3C).

(A) Systolic blood pressure (SBP), (B) diastolic blood pressure (DBP), and (C) heart rate before (pre) and after (post) kurort health walking. Significant decreases were seen in (A) SBP (from 130.5±18.4 to 124.4±16.8 mmHg; n=454; P<0.0001, paired Student’s t-test) and (B) DBP (from 81.6±11.3 to 80.6±11.8 mmHg; n=454; P=0.0203, paired Student’s t-test), and (C) heart rate increased significantly (from 73.1±12.1 to 75.8±12.3 beats/min; n=415; P<0.0001, paired Student’s t-test). Data are presented as the mean±SD.

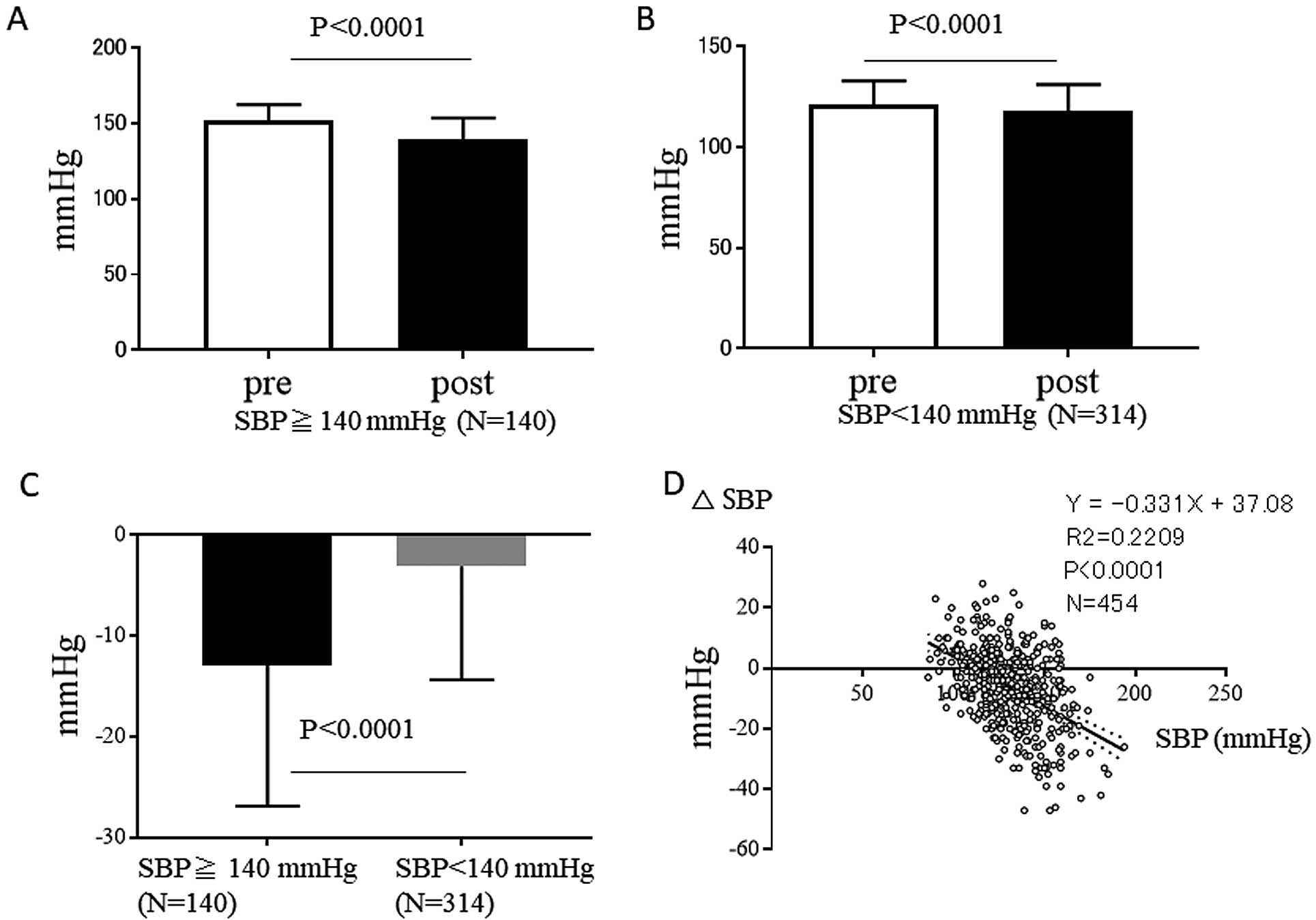

In the SBP ≥140 mmHg group, SBP decreased significantly from 152.2±10.2 to 139.1±14.6 mmHg (P<0.0001; n=140; Figure 4A), whereas in the SBP <140 mmHg group SBP decreased significantly from 120.9±11.9 to 117.8±13.2 mmHg (P<0.0001; n=314; Figure 4B). The decrease in SBP was significantly greater in the SBP ≥140 mmHg group (−12.9±13.9 mmHg; n=140) than in the SBP <140 mmHg group (−3.0±11.2 mmHg; n=314; P<0.0001; Figure 4C). Thus, there was an inverse correlation between SBP before kurort health walking and the change in SBP after kurort health walking (P<0.0001; Figure 4D).

Kurort health walking-induced changes in systolic blood pressure (SBP) in participants according to SBP before kurort health walking (≥140 vs. <140 mmHg). (A) In participants with SBP ≥140 mmHg, kurort health walking significantly decreased SBP (152.2±10.2 to 139.1±14.6 mmHg; n=140; P<0.0001, paired Student’s t-test). (B) In participants with SBP <140 mmHg, kurort health walking significantly decreased SBP (from 120.9±11.9 to 117.8±13.2 mmHg; n=314; P<0.0001, paired Student’s t-test). (C) The decrease in SBP due to kurort health walking was significantly greater in the SBP ≥140 than <140 mmHg group, with changes in SBP (∆SBP) of −12.9±13.9 mmHg (n=140) and −3.0±11.2 mmHg (n=314), respectively (P<0.0001, unpaired Student’s t-test). Data are presented as the mean±SD. (D) Relationship between SBP and ∆SBP. There was an inverse correlation between SBP before kurort health walking and ∆SBP (P<0.0001).

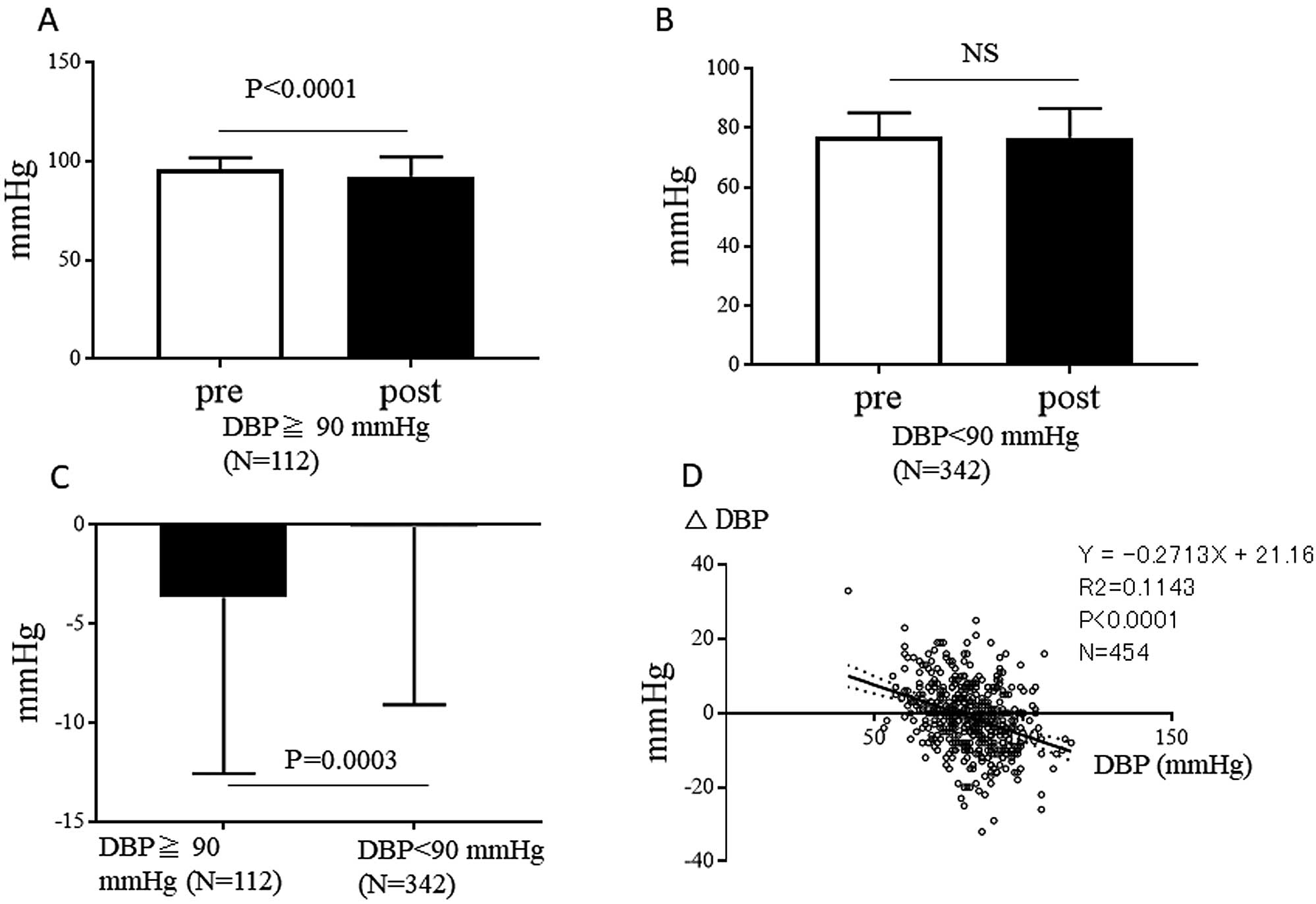

In the DBP ≥90 mmHg group, DBP decreased significantly from 96.1±5.6 to 92.4±9.7mmHg (P<0.0001; n=112; Figure 5A). In the DBP <90 mmHg group, DBP decreased from 76.8±8.2 to 76.7±9.7mmHg (n=342), but the difference did not reach statistical significance (P=0.823; Figure 5B). The decrease in DBP was significantly greater in the DBP ≥90 mmHg group (−3.6±8.8mmHg; n=112) than in the SBP <90 mmHg group (−0.1±8.9mmHg; n=342; P=0.0003; Figure 5C). Thus, there was an inverse correlation between DBP before kurort health walking and the change in DBP after kurort health walking (P<0.0001; n=454; Figure 5D).

Kurort health walking-induced changes in diastolic blood pressure (DBP) in participants according to DBP before kurort health walking (≥90 vs. <90 mmHg). (A) In participants with DBP ≥90 mmHg, kurort health walking significantly decreased DBP (from 96.1±5.6 to 92.4±9.7 mmHg; n=112; P<0.0001, paired Student’s t-test). (B) In participants with DBP <90 mmHg, kurort health walking decreased DBP from 76.8±8.2 to 76.7±9.7 mmHg (n=342), but the difference did not reach statistical significance (P=0.823, paired Student’s t-test). (C) The decrease in DBP due to kurort health walking was significantly greater in the DBP ≥90 than <90 mmHg group, with changes in DBP (∆DBP) of −3.6±8.8 mmHg (n=112) and −0.1±8.9 mmHg (n=342), respectively (P=0.0003, unpaired Student’s t-test). Data are presented as the mean±SD. (D) Relationship between DBP and ∆DBP. There was an inverse correlation between DBP before kurort health walking and ∆DBP (P<0.0001; n=454).

Kurort health walking significantly improved scores for each of the mood items, namely feeling lively (mean score after walking 0.65±0.47; P<0.0001 compared with before walking), feeling refreshed (0.87±0.33; P<0.0001), a vivid feeling (0.65±0.48; P<0.0001), feeling exhilarated (0.82±0.38; P<0.0001), feeling relaxed (0.77±0.41; P<0.0001), feeling calm (0.65±0.47; P<0.0001), a fun feeling (0.74±0.43; P<0.0001), feeling anxious (0.44±0.49; P<0.0001), feeling irritated (0.51±0.50; P<0.0001), and feeling tired (0.40±0.52; P<0.0001). In addition, kurort health walking significantly improved the sum score of the 10 mood items (mean score after walking 6.5±3.2 out of perfect score of 10; P<0.0001 compared with before walking; Figure 6).

Effects of kurort health walking on changes in mood. Improvements were seen in all 10 mood items evaluated on the checklist after kurort health walking. Changes in mood items after kurort health walking were rated as improved (score=1), no change (score=0), or worsened (score=−1). For each item, the mean±SD scores before and after kurort health walking are shown, with percentages for each category (1, improved; 0, no change; −1, worsened) across all 454 participants also presented. Changes in mood items from before to after kurort health walking were assessed by paired Student’s t-test.

The major findings of the present study are that: (1) kurort health walking in the courses in Gifu City decreased both SBP and DBP; (2) the decrease in SBP was significantly greater in the SBP ≥140 than <140 mmHg group, and the change in SBP was inversely correlated with SBP before walking; (3) the decrease in DBP was significantly greater in the DBP ≥90 than <90 mmHg group, and the change in DBP was inversely correlated with DBP before walking; and (4) kurort health walking improved mood.

Recently in Japan, the popularity of kurort health walking has gradually increased with the support of local governments and companies. The 2 kurort health walking courses in Gifu City are well designed and well maintained by the Gifu City administration; thus, walking through these courses may improve participants’ physical condition and mood by relieving physical and mental tension by attenuating augmented sympathetic nerve activity. In the present study, kurort health walking decreased SBP and DBP (Figure 3A,B) and significantly increased heart rate (Figure 3C). On average, kurort health walking decreased SBP by 6.1 mmHg, decreased DBP by 1 mmHg, and increased heart rate by 2.7 beats/min. The increase in heart rate after exercise such as walking is a physiologically normal response, and an increase in heart rate of 2.7 beats/min is very small and can be regarded as safe (Figure 3C). Checking participants’ heart rate during kurort health walking to ensure that it was maintained under the target rate (calculated as [160−age] beats/min) meant that kurort health walking was performed safely.

When participants were divided into 2 groups based on SBP before kurort health walking (i.e., SBP ≥140 and <140 mmHg), the decrease in SBP after kurort health walking was significantly greater in the SBP ≥140 than <140 group (−12.9±13.9 vs. −3.0±11.2 mmHg, respectively; P<0.0001), indicating that the higher the SBP, the greater the decrease in SBP after kurort health walking (Figure 4D). When participants were divided into 2 groups based on DBP before kurort health walking (i.e., DBP ≥90 and <90 mmHg), the decrease in DBP after kurort health walking was significantly greater in the DBP ≥90 than <90 mmHg group (−3.6±8.8 vs. −0.1±8.9 mmHg, respectively; P=0.0003), indicating that the higher the DBP, the greater the decrease in DBP (Figure 5D). Furthermore, as shown in Figures 4D and 5D, there is an inverse correlation between SBP and DBP before kurort health walking and the change in SBP and DBP after kurort health walking. Kurort health walking preferentially decreased higher than lower blood pressure and was safely performed even by hypertensive patients with SBP ≥140 mmHg and DBP ≥90 mmHg, decreasing their high blood pressure (Figures 4,5). Based on these findings, kurort health walking may be a useful strategy to reduce SBP and DBP in hypertensive patients. It has previously been reported that aerobic exercise decreases both SBP and DBP in both hypertensive patients and normotensive subjects.8–11 The precise mechanisms by which aerobic exercise decreases blood pressure have not been fully clarified; however, some possible mechanisms have been suggested, including attenuation of plasma norepinephrine and epinephrine concentrations and enhancement of plasma prostaglandin E concentrations by aerobic exercise.8

Kurort health walking also improved all 10 mood items (Figure 6). Of the 10 items evaluated, scores for feeling refreshed (0.87±0.33), feeling exhilarated (0.82±0.38), feeling relaxed (0.77±0.41), and a fun feeling (0.74±0.43) were higher, suggesting that these 4 feelings were greatly improved by kurort health walking. Furthermore, the sum of all 10 mood items was 6.5±3.2 (out of perfect score of 10); hence, more than 65% of participants showed an improvement in the sum of all 10 mood items following kurort health walking. These results suggest that kurort health walking may relieve mental tension and bring about an improvement in mood. Based on these results, kurort health walking may be a therapeutic strategy for improving mental health status. Previous studies found that aerobic exercise improved mental health status in patients with diabetes and depressive disorders,12,13 and others have reported that people who do not walk outside their home show more depressive symptoms or a greater likelihood of clinical depression.14 These reports may explain the beneficial effect of the kurort health walking in Gifu City, which consisted of walking outdoors, on mental health status. Because hypertension and mental health status have been reported to be associated with cardiovascular events,1–3 kurort health walking may be effective in reducing the risk of cardiovascular events because it decreases SBP and DBP and improves mood.

The advantages of kurort walking in Gifu City compared with normal walking may be that: (1) participants can walk in areas rich in nature, such as scenic hills, forests, rivers, and hot springs, and in a good climate,3 resulting in good mental feelings; (2) participants are accompanied by 2 health exercise instructors who provide appropriate advice during the walk; (3) blood pressure is measured before and after walking; and (4) heart rate during walking is maintained below the target rate, defined as (160−age) beats/min, by checking heart rate at various points over the course to ensure safety (Figures 1,2).

Study LimitationsThis study only showed the short-term effects of a single bout of exercise. The long-term effects of kurort health walking on blood pressure and mood remain to be investigated. Because the participants in the kurort health walking program are general citizens of Gifu City who happened to take part in the program, we only recorded whether they had hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia, which are risk factors for coronary artery disease, on the checklist and did not obtain information regarding a history of cardiac and pulmonary diseases or drugs used. Furthermore, it is quite difficult to take blood samples from citizens who take part in kurort walking in the outdoors, although a survey based on blood data, such as blood glucose level, HbA1c, and cholesterol concentrations, may be important. However, because kurort health walking can be regarded as a type of outdoor cardiac rehabilitation, information regarding a history of cardiac disease should have been obtained.

Clinical PerspectivesIn this study, SBP and DBP decreased and mood improved in subjects who participated in the kurort health walking program in Gifu City. Of all the participants, approximately 30% had a history of hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia, which are risk factors for coronary artery disease.15 Even in these participants, kurort health walking was performed safely. The present study was performed between June 1, 2020 and May 30, 2021, during the coronavirus pandemic, suggesting that because kurort health walking is mostly an outdoor activity, it can be safely performed in the coronavirus era.

In addition to effectively decreasing blood pressure and improving mood, kurort health walking could be an alternative tool for cardiac rehabilitation. Because cardiac rehabilitation has recently been reported to improve the prognosis of cardiac diseases such as acute myocardial infarction and heart failure,16,17 cardiac rehabilitation is recommended for these patients in the guidelines from the Japanese Circulation Society18 and as part of the standard cardiac rehabilitation program for heart failure from the Japanese Association of Cardiac Rehabilitation Standard Cardiac Rehabilitation Program Planning Committee.19 However, under the health insurance system in Japan, cardiac rehabilitation is limited to 20 weeks after the onset of cardiac diseases. Thus, kurort health walking may be a suitable option for maintaining the health of cardiac patients after they have completed 20 weeks of cardiac rehabilitation. Further investigations are warranted.

The authors are grateful for the support of the Health Promotion Section of Gifu Municipal Office, Gifu City, Japan.

This study was funded from the Sugiura Memorial Foundation, Obu City, Aichi, Japan.

S.M.: organization and design of the study, data interpretation and analysis, manuscript writing, financial support, and final approval of manuscript. T.M., K.N., S.O., S.Y.: data collection and data interpretation, K.O.: data analysis, S.T., M.S., M.O., T.M.: organization of kurort health walking and data collection.

S.M. is a member of Circulation Reports’ Editorial Team. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Gifu Municipal Hospital (Approval no. 634).

The deidentified participant data will not be shared.