2023 年 5 巻 4 号 p. 133-143

2023 年 5 巻 4 号 p. 133-143

Background: The purpose of this study was to investigate the actual conditions of cardiac rehabilitation (CR) for elderly patients with heart failure (HF) in outpatient rehabilitation (OR) facilities using long-term care insurance systems.

Methods and Results: This was a cross-sectional web-based questionnaire survey conducted at 1,258 facilities in the Kansai region (6 prefectures) of Japan from October to December 2021. In all, 184 facilities responded to the web-based questionnaire (response rate 14.8%). Of these facilities, 159 (86.4%) accepted patients with HF. Among the patients with HF, 94.3% were aged ≥75 years and 66.7% were classified as New York Heart Association functional class I/II. Facilities treating patients with HF generally provided exercise therapy, patient education, and disease management, which were components of CR. Many facilities not currently treating patients with HF responded positively stating they will accept HF patients in the future. However, a few facilities responded by stating that they are waiting for clearer evidence demonstrating the beneficial effect of OR on patients with HF.

Conclusions: The present results show the possibility that outpatient CR can be performed for elderly patients with HF in other than medical insurance.

Heart failure (HF) is one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide, and is a concerning public health problem.1,2 In the aging Japanese population, the rapidly increasing prevalence of HF, known as the HF pandemic,3 is expected to reach approximately 1.3 million by 2030.4 HF is characterized by a high rate of rehospitalization compared with other diseases.1,2 Exercise tolerance is associated with prognosis in HF patients.5 Therefore, an important factor in preventing the recurrence of HF is to continue exercising after hospital discharge and to maintain and improve the amount of appropriate physical activity in daily life.6,7

It is recommended that cardiac rehabilitation (CR) is continued after discharge from an acute care hospital, and outpatient CR contributes to improved prognosis.6,7 However, although the inpatient CR participation rate of patients with cardiovascular disease increased in Japan from 2010 to 2017 as the number of hospitals accredited for CR increased, the utilization rate of outpatient CR has remained extremely low since 2007.8 Barriers to participation in CR are reported as old age, rural residency, and transportation issues.9 Thus, many elderly patients with HF have no choice but to abandon participation in outpatient CR because of physical or cognitive problems. Decreased physical activity after discharge has been observed in many cases, leading to disuse syndrome and recurrent HF hospitalizations.10

In Japan, the Long-Term Care Insurance (LTCI) System supports the elderly who need nursing care in society as a whole.11,12 Outpatient rehabilitation (OR) is defined as an in-home service offered by LTCI that can provide “maintenance and recovery training of functions” and “training for activities of daily living” by rehabilitation staff such as physical therapists (PT), occupational therapists (OT), and speech therapists, who provide services at geriatric health services facilities for the elderly and facilities attached to a hospital or clinic.13 Unlike medical outpatient services, OR is included in a service that can provide transportation for elderly patients between the facility and their homes.13

Support for elderly patients with HF and their caregivers through therapeutic exercise provided by a multidisciplinary team comprising various healthcare professionals in their local area after discharge from hospital is expected to improve prognosis and quality of life.14,15 If CR at OR facilities using LTCI systems is realized, it is expected to help elderly patients with HF who cannot attend outpatient CR at medical institutions to maintain and improve their health, and to contribute to the prevention of recurrent HF hospitalizations. Therefore, promoting CR at OR facilities is crucial to maintain an appropriate amount of physical activity in elderly patients with HF.

In Japan, there are 7,920 OR facilities nationwide (as of 2019), and the number is increasing,13 but the number of OR facilities offering CR is unknown. OR facilities offering CR in a capital city (often Tokyo) area have been reported,16 although no study has reported OR facilities offering CR outside these areas. Moreover, there are no reports on the rehabilitation regimens at OR facilities for patients with HF and other diseases. Clarifying CR regimens provided at OR facilities can provide valuable clinical information on the CR provided as part of LTCI systems. Therefore, the purpose of the present study was to investigate the actual conditions of CR provided at OR facilities using LTCI systems in the Kansai region.

This survey was a cross-sectional self-reported web-based questionnaire. Participating OR facilities were selected in the Kansai region using purposive sampling. Inclusion criteria included 1,258 OR facilities that were registered with Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare publication system for long-term care service information17 in the Kansai region (6 prefectures: Hyogo, Osaka, Kyoto, Wakayama, Shiga, Nara) of Japan as of July 1, 2021. There were no exclusion criteria.

Ethics StatementThe Ethics Committee of Hyogo College of Medicine approved this survey (No. 3877), which was registered with the University Hospital Medical Information Network (UMIN) Clinical Trials Registry (ID: UMIN000045252). We conducted the survey in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants could freely decide whether or not to participate in the survey, and their decision was captured at the beginning of the web-based questionnaire.

QuestionnaireThe questionnaire was developed by 4 medical and nursing care experts in CR (two doctors and PT/OT involved in CR, including a councilor of the Japanese Association of CR) based on the official Japanese Circulation Society (JCS) guidelines for HF,14,18 and comprised a total of 19 questions and 57 items. The questionnaire was filled in by a responder from each of the accepting and non-accepting facilities for patients with HF. In facilities accepting patients with HF, HF was defined as a “heart disease or HF” diagnosis on the medical information form that was made by a physician from the facility. The questionnaire consisted of 5 sections: rehabilitation; disease management; medical and nursing care coordination; need for CR at OR facilities; and reasons for difficulty in accepting patients with HF (only for non-accepting facilities). The questionnaire could be completed within 15 min. This report describes the results of the following 3 sections: rehabilitation; disease management; and reasons for difficulty in accepting patients with HF.

Data CollectionThe survey description, including a link to the web-based questionnaire, was sent to a representative from each facility by invitation email. The questionnaire was available for completion from October 2021 to December 2021. No reminder was sent. Incentives, in the form of a gift card, were offered to each representative who completed the survey.

Google Forms (Google LLC; https://www.google.com/intl/ja_jp/forms/about/) was used as the data collection platform. To prevent missing information, registration errors were generated if required/necessary items were not filled in.

Statistical AnalysisPercentages of responses were computed and compared between facilities using Pearson’s Chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test and the Brunner Munzel test, with significance set at two-sided P<0.05. Data were analyzed using JMP® pro15 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA; https://www.jmp.com/ja_jp/home.html) and HAD 16 (H. Shimizu, Hyogo, Japan; https://norimune.net/had).19

The survey description, including a link to the web-based questionnaire, could only be sent to 1,242 facilities due to 16 exclusions, 3 of which were duplicate registrations and 13 returns (11 with no fixed address and 2 with a suspension of business). The response rate of the web-based questionnaire was 14.8% (184 facilities). There were no missing data. Demographic data and characteristics of the survey facilities are presented in Table 1. Of the 184 facilities, 159 (86.4%) accepted patients with HF. Respondents were mostly PT (70.0%) and there was no significant difference in the number of years of experience of staff between facilities that did and did not accept patients with HF (P=0.195). Only a few of the medical staff at each facility were qualified to provide CR to patients with cardiovascular disease, including the JCS-certified board member, registered CR instructor, and nurses certified in chronic HF care (2.5%, 3.8%, and 0.6%, respectively). The characteristics of patients at OR facilities are presented in Table 2. Of the patients with HF, 94.3% were aged ≥75 years and 66.7% were classified as New York Heart Association (NYHA) Class I/II.

| Total (n=184) |

Facilities accepting patients with HF (n=159) |

Facilities not accepting patients with HF (n=25) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Responder occupation | ||||

| PT | 128 (70.0) | 113 (71.1) | 15 (60.0) | 0.055 |

| OT | 25 (14.0) | 24 (15.1) | 1 (4.0) | |

| Doctor | 2 (1.0) | 1 (0.6) | 1 (4.0) | |

| Nurse/associate nurse | 7 (4.0) | 5 (3.1) | 2 (8.0) | |

| Certified social worker | 2 (1.0) | 2 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Long-term care support specialist | 1 (1.0) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Health fitness programmer | 1 (1.0) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Case worker | 7 (4.0) | 4 (2.5) | 3 (12.0) | |

| Nursing care worker/nursing staff | 5 (3.0) | 4 (2.5) | 1 (4.0) | |

| Others | 6 (3.0) | 4 (2.5) | 2 (8.0) | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 134 (73.0) | 114 (71.7) | 20 (80.0) | 0.386 |

| Female | 50 (27.0) | 45 (28.3) | 5 (20.0) | |

| Years of clinical experience | 13 [18–10] | 14 [19–10] | 13 [16.5–5] | 0.195 |

| Area (prefecture) | ||||

| Hyogo | 63 (34.0) | 55 (34.6) | 8 (32.0) | 0.384 |

| Osaka | 68 (37.0) | 59 (37.1) | 9 (36.0) | |

| Nara | 10 (5.0) | 7 (4.4) | 3 (12.0) | |

| Kyoto | 14 (8.0) | 12 (7.5) | 2 (8.0) | |

| Shiga | 21 (11.0) | 20 (12.6) | 1 (4.0) | |

| Wakayama | 8 (4.0) | 6 (3.8) | 2 (8.0) | |

| Facility* | ||||

| Medical institution (hospital/clinic) | 121 (66.0) | 100 (62.9) | 21 (84.0) | 0.039 |

| Geriatric health services facilities | 63 (34.0) | 59 (37.1) | 4 (16.0) | |

| Facility scale* | ||||

| Normal | 159 (86.0) | 134 (84.3) | 25 (100.0) | 0.033 |

| Large | 25 (14.0) | 25 (15.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Attached to medical institution | ||||

| Yes | 144 (78.0) | 122 (76.7) | 22 (88.0) | 0.204 |

| No | 40 (22.0) | 37 (23.3) | 3 (12.0) | |

| Facility staffing (multiple answers) | ||||

| Full-time doctor** | 158 (86.0) | 141 (88.7) | 17 (68.0) | 0.006 |

| Part-time doctor | 46 (25.0) | 41 (25.8) | 5 (20.0) | 0.535 |

| PT** | 176 (96.0) | 154 (96.9) | 22 (88.0) | 0.004 |

| OT* | 108 (59.0) | 98 (61.6) | 10 (40.0) | 0.041 |

| ST** | 68 (37.0) | 65 (40.9) | 3 (12.0) | 0.005 |

| Nurse* | 126 (68.0) | 114 (71.7) | 12 (48.0) | 0.018 |

| Associate nurse | 51 (28.0) | 48 (30.2) | 3 (12.0) | 0.059 |

| Registered dietitian/nutritionist | 75 (41.0) | 69 (43.4) | 6 (24.0) | 0.067 |

| Case worker* | 70 (38.0) | 66 (41.5) | 4 (16.0) | 0.015 |

| Long-term care support specialists* | 73 (40.0) | 68 (42.8) | 5 (20.0) | 0.031 |

| Nursing care worker/nursing staff** | 140 (76.0) | 127 (79.9) | 13 (52.0) | 0.002 |

| Certification (multiple answers) | ||||

| JCS-certified board member | 4 (2.0) | 4 (2.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0.423 |

| Registered instructor of CR | 6 (3.0) | 6 (3.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0.975 |

| Advanced instructor of CR | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | – |

| CHFEJ | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | – |

| Nurses certified in chronic HF nursing | 1 (1.0) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0.691 |

| Others | 4 (2.0) | 3 (1.9) | 1 (4.0) | 0.501 |

| Onsite BLS training** | ||||

| Yes | 74 (40.0) | 70 (44.0) | 4 (16.0) | 0.008 |

| No | 110 (60.0) | 89 (56.0) | 21 (84.0) | |

| Mean hours service used** | ||||

| 1–2 | 61 (33.0) | 45 (28.3) | 16 (64.0) | 0.004 |

| 2–3 | 3 (2.0) | 2 (1.3) | 1 (4.0) | |

| 3–4 | 20 (11.0) | 20 (12.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 4–6 | 17 (9.0) | 17 (10.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 6–8 | 82 (45.0) | 74 (46.5) | 8 (32.0) | |

| ≥8 | 1 (1.0) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Mean number of times used | ||||

| Once a month | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.264 |

| Once a week | 20 (11.0) | 15 (9.4) | 5 (20.0) | |

| Twice a week | 132 (72.0) | 115 (72.3) | 17 (68.0) | |

| ≥3 times a week | 32 (17.0) | 29 (18.2) | 3 (12.0) | |

| Mean no. total daily users | ||||

| 1–10 people | 28 (15.0) | 19 (11.9) | 9 (36.0) | 0.180 |

| 11–20 people | 46 (25.0) | 38 (23.9) | 8 (32.0) | |

| 21–30 people | 49 (27.0) | 43 (27.0) | 6 (24.0) | |

| 31–40 people | 31 (17.0) | 29 (18.2) | 2 (8.0) | |

| 41–50 people | 12 (7.0) | 12 (7.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 51–60 people | 7 (4.0) | 7 (4.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 61–70 people | 5 (3.0) | 5 (3.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 71–80 people | 3 (2.0) | 3 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 81–90 people | 2 (1.0) | 2 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 91–99 people | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| ≥100 people | 1 (1.0) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

Unless indicated otherwise, data are given as the median [interquartile range] or n (%). *P<0.05, **P<0.01 between accepting and non-accepting facilities. Normal: the average number of 750 patients less than; Large: the average number of 750 patients or more. BLS, Basic Life Support; CHFEJ, Certified Heart Failure Educator of Japan; CR, Cardiac Rehabilitation; HF, heart failure; JCS, Japanese Circulation Society; OT, occupational therapist; PT, physical therapist; ST, speech therapist.

| Total (n=184) |

Facilities accepting patients with HF (n=159) |

Facilities not accepting patients with HF (n=25) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ratio of male to female** | ||||

| More men | 54 (29.0) | 54 (34.0) | 0 (0.0) | <0.001 |

| More women | 65 (35.0) | 44 (27.7) | 21 (84.0) | |

| About equal numbers of men and women | 65 (35.0) | 61 (38.4) | 4 (16.0) | |

| Age group distribution** | ||||

| <64 years | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.009 |

| 65–69 years | 3 (2.0) | 3 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 70–74 years | 10 (5.0) | 6 (3.8) | 4 (16.0) | |

| 75–79 years | 25 (14.0) | 19 (11.9) | 6 (24.0) | |

| 80–84 years | 88 (48.0) | 77 (48.4) | 11 (44.0) | |

| 85–89 years | 49 (27.0) | 45 (28.3) | 4 (16.0) | |

| ≥90years | 9 (5.0) | 9 (5.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Complication (multiple answers) | ||||

| Malignant growth | 8 (4.0) | 7 (4.4) | 1 (4.0) | 0.927 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 122 (66.0) | 107 (67.3) | 15 (60.0) | 0.473 |

| Disuse syndrome | 143 (78.0) | 127 (79.9) | 16 (64.0) | 0.076 |

| Respiratory disease | 53 (29.0) | 47 (29.6) | 6 (24.0) | 0.568 |

| Kidney disease | 26 (14.0) | 25 (15.7) | 1 (4.0) | 0.118 |

| Liver disease | 1 (1.0) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0.691 |

| Musculoskeletal disease (lower limb)* | 149 (81.0) | 125 (78.6) | 24 (96.0) | 0.040 |

| Musculoskeletal diseases (spine)* | 102 (55.0) | 83 (52.2) | 19 (76.0) | 0.026 |

| Neuromuscular diseases* | 57 (31.0) | 44 (27.7) | 13 (52.0) | 0.015 |

| Metabolic diseases | 16 (9.0) | 14 (8.8) | 2 (8.0) | 0.984 |

| Others | 2 (1.0) | 2 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0.573 |

| None | 4 (2.0) | 4 (2.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0.643 |

| Level of care needed | ||||

| Requiring help 1 | 2 (1.0) | 5 (3.1) | 2 (8.0) | 0.112 |

| Requiring help 2 | 2 (1.0) | 22 (13.8) | 9 (36.0) | |

| Long-term care 1 | 28 (15.0) | 50 (31.4) | 3 (12.0) | |

| Long-term care 2 | 61 (33.0) | 53 (33.3) | 8 (32.0) | |

| Long-term care 3 | 53 (29.0) | 25 (15.7) | 3 (12.0) | |

| Long-term care 4 | 31 (17.0) | 2 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Long-term care 5 | 7 (4.0) | 2 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Bed-fast scale20 | ||||

| Independence | 5 (3.0) | 4 (2.5) | 1 (4.0) | 0.357 |

| J1 | 19 (10.0) | 17 (10.7) | 2 (8.0) | |

| J2 | 29 (16.0) | 23 (14.5) | 6 (24.0) | |

| A1 | 65 (35.0) | 56 (35.2) | 9 (36.0) | |

| A2 | 55 (30.0) | 49 (30.8) | 6 (24.0) | |

| B1 | 8 (4.0) | 7 (4.4) | 1 (4.0) | |

| B2 | 2 (1.0) | 2 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| C1 | 1 (1.0) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| C2 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Dementia scale20 | ||||

| Independence | 28 (15.0) | 21 (13.2) | 7 (28.0) | 0.270 |

| I | 49 (27.0) | 45 (28.3) | 4 (16.0) | |

| II | 45 (24.0) | 37 (23.3) | 8 (32.0) | |

| IIa | 33 (18.0) | 30 (18.9) | 3 (12.0) | |

| IIb | 24 (13.0) | 21 (13.2) | 3 (12.0) | |

| III | 2 (1.0) | 2 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| IIIa | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| IIIb | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| IV | 2 (1.0) | 2 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| M | 1 (1.0) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| New York Heart Association functional class | ||||

| I | NA | 26 (16.4) | NA | |

| II | NA | 80 (50.3) | NA | |

| III | NA | 52 (32.7) | NA | |

| IV | NA | 1 (0.6) | NA | |

| % Patients with HF per day | ||||

| 1–10 | NA | 106 (66.7) | NA | |

| 11–20 | NA | 34 (21.4) | NA | |

| 21–30 | NA | 11 (6.9) | NA | |

| 31–40 | NA | 6 (3.8) | NA | |

| 41–50 | NA | 1 (0.6) | NA | |

| 51–60 | NA | 0 (0.0) | NA | |

| 61–70 | NA | 0 (0.0) | NA | |

| 71–80 | NA | 1 (0.6) | NA | |

| 81–90 | NA | 0 (0.0) | NA | |

| 91–100 | NA | 0 (0.0) | NA | |

Unless indicated otherwise, data are presented as n (%). Accepting facilities are those accepting patients with heart failure (HF) only, whereas non-accepting facilities are for patients with diseases other than HF. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 between accepting and non-accepting facilities. Level of care needed refers to patients who are certified as requiring help or long-term care. Requiring help 1: A person who can perform basic activities of daily living but needs some assistance; Requiring help 2: In addition to the status of Requiring help 1, the patient is unsteady in walking and has limited ability to do things on his/her own; Long-term care 1: Patients with physical and thinking abilities worse than those in need of Requiring help 2, and need nursing care for part of their daily activities; Long-term care 2: Patients require assistance with basic activities of daily living. Cognitive functions are also deteriorating; Long-term care 3: Patient needs assistance with almost all activities of daily living; Long-term care 4: A condition requiring constant nursing care; Long-term care 5: Almost bedridden. Bed-fast scale, criteria for evaluating the degree of independence of disabled elderly persons in performing activities of daily living; Dementia scale, criteria for evaluating the degree of independence of elderly persons with dementia in performing activities of daily living; NA, not applicable. Refer to reference 20 (Maruta 2019) for the Bed-fast scale and Dementia scale.

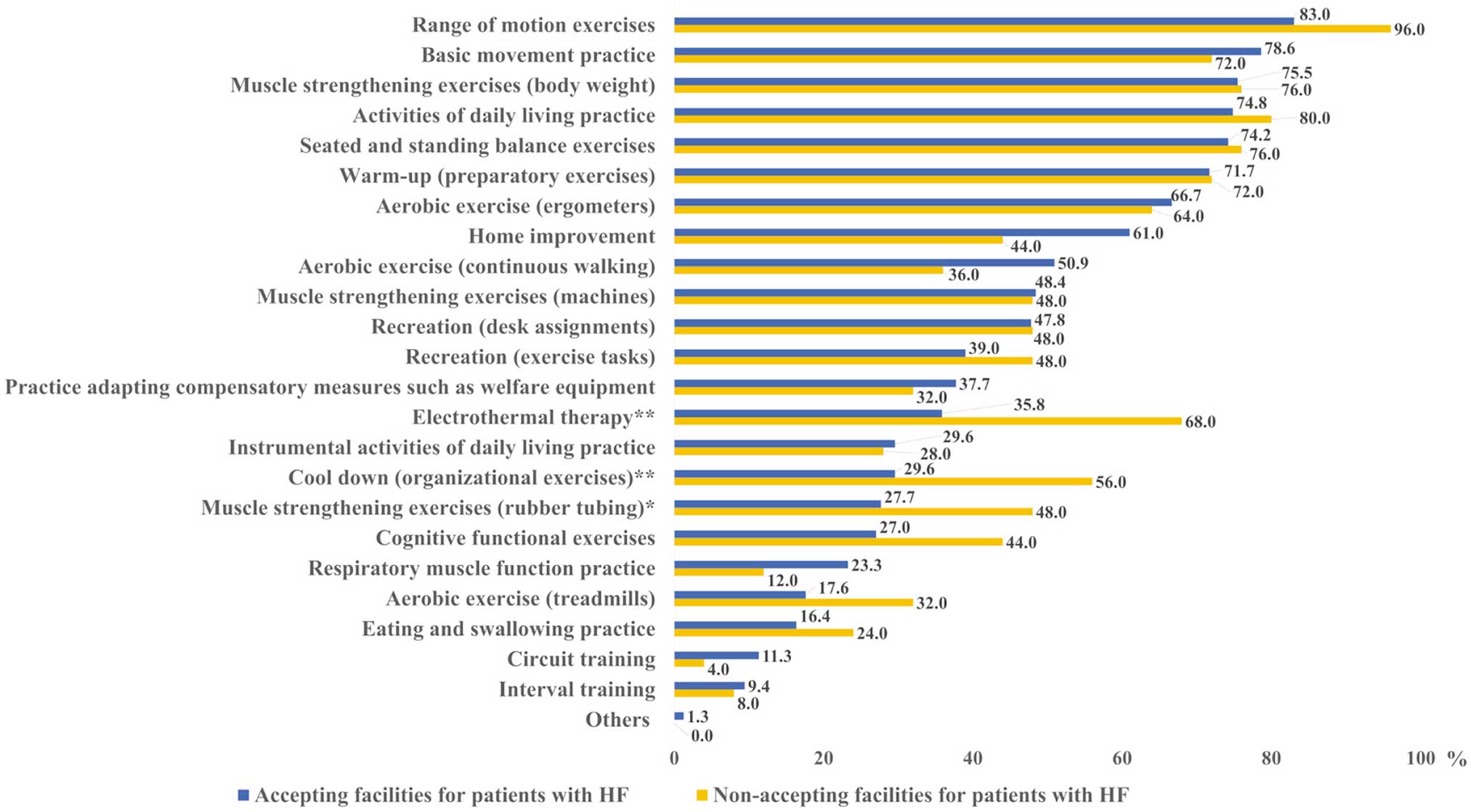

Content of Rehabilitation Programs The content of the rehabilitation programs is shown in Figure 1. In both accepting and non-accepting facilities, “joint range of motion practice”, “basic movement practice”, “daily living practice”, and “muscle strength practice (body weight)” were most frequently selected. The selection of “electrothermal therapy”, “cool down”, and “muscle strengthening exercise (rubber tube)” was significantly higher for non-accepting facilities (P=0.002, P=0.009, and P=0.040, respectively).

Rehabilitation in outpatient rehabilitation facilities (multiple answers allowed). Accepting facilities are for patients with heart failure (HF) only, whereas non-accepting facilities are for patients with diseases other than HF. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 between accepting and non-accepting facilities.

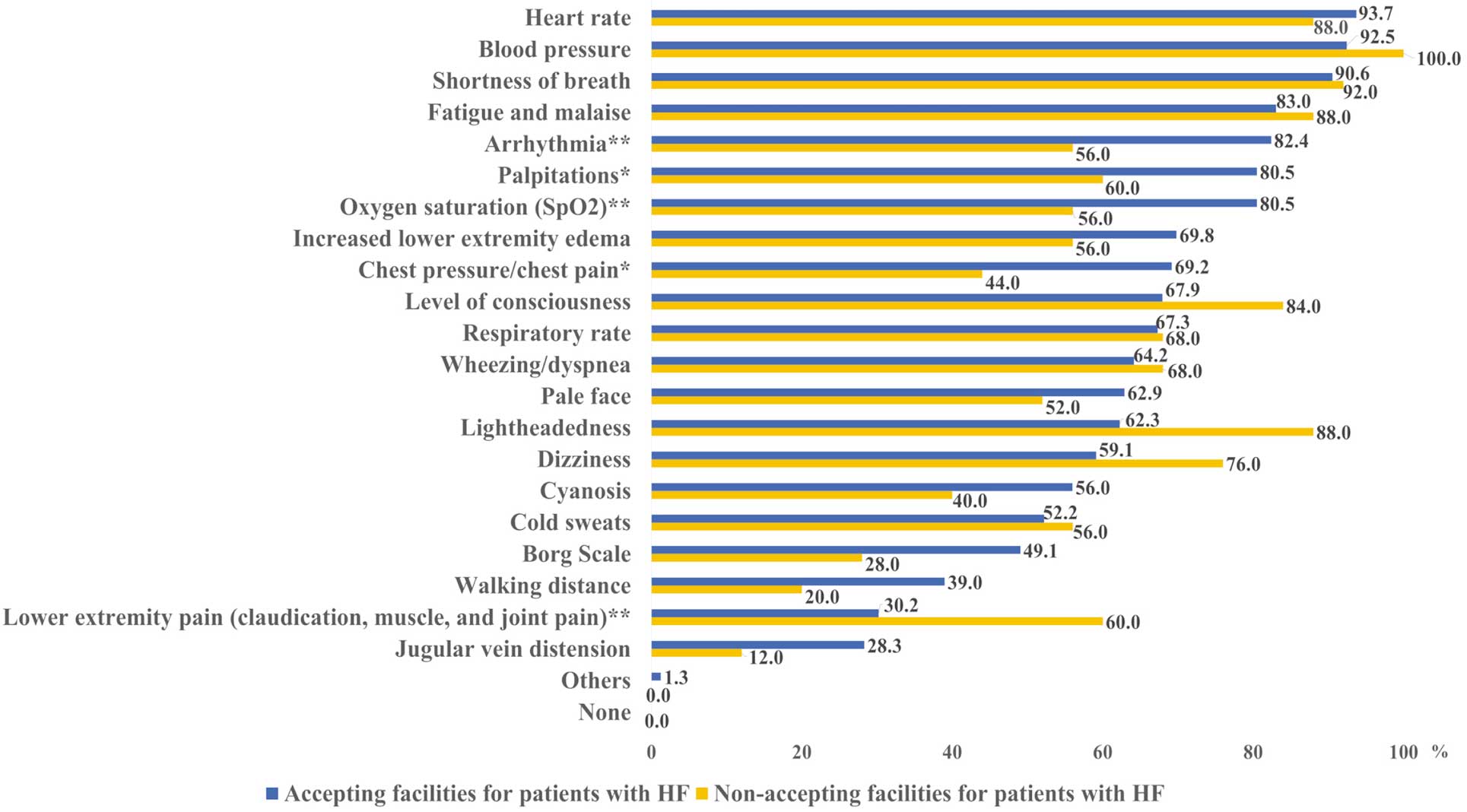

Risk Management Indicators for risk management in rehabilitation are shown in Figure 2. In both accepting and non-accepting facilities, “heart rate”, “blood pressure”, “shortness of breath”, and “fatigue/weariness” were most frequently selected. Accepting facilities significantly more frequently selected “arrhythmia”, “oxygen saturation (SpO2)”, “palpitations”, and “chest pressure/chest pain” (P=0.003, P=0.007, P=0.022, and P=0.014, respectively), whereas “lightheadedness” and “lower limb pain (claudication, muscle/joint pain)” were significantly more often selected by non-accepting facilities (P=0.012 and P=0.004, respectively).

Indicators for risk management in rehabilitation (multiple answers allowed). Accepting facilities are for patients with heart failure (HF) only, whereas non-accepting facilities are for patients with diseases other than HF. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 between accepting and non-accepting facilities.

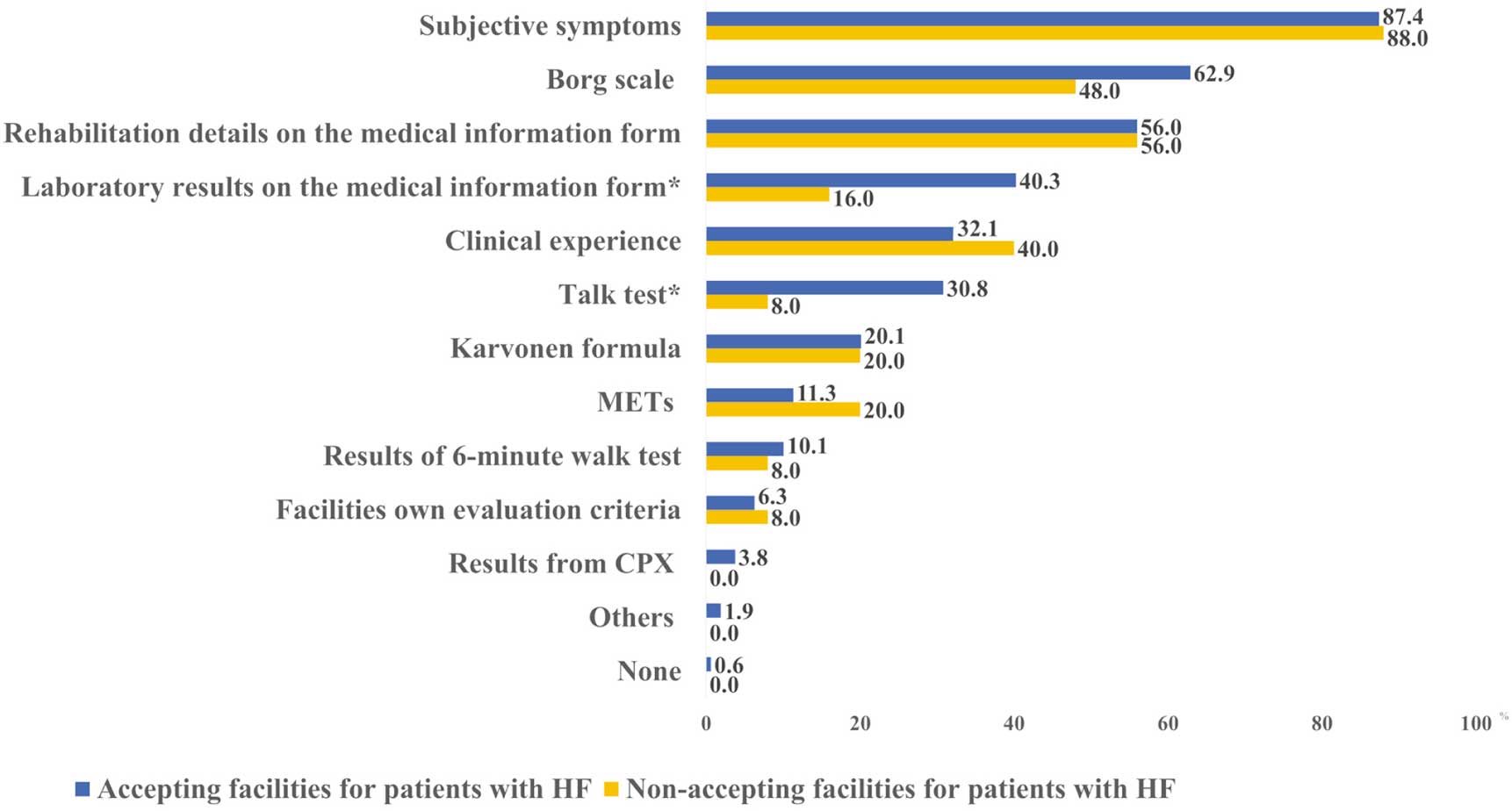

Exercise Load Indicators of exercise load in rehabilitation are shown in Figure 3. The most common response was “subjective symptoms” in both accepting and non-accepting facilities, and “Karvonen formula” and “results of 6-min walk test” were selected less frequently. Accepting facilities significantly more frequently selected “test results on the medical information form” and “talk test” (P=0.020 and P=0.018, respectively).

Indicators of exercise load in rehabilitation (top 5 answers). Accepting facilities are for patients with heart failure (HF) only, whereas non-accepting facilities are for patients with diseases other than HF. *P<0.05 between accepting and non-accepting facilities. CPX, cardiopulmonary pulmonary exercise test; METs, metabolic equivalents.

Lifestyle Guidance The most common lifestyle guidance category for patients in OR facilities was “guidance on exercise and activity level” in both accepting and non-accepting facilities. The “salt intake” (34.6% of accepting facilities and 8.0% of non-accepting facilities; P=0.008) and “smoking cessation” (20.1% of accepting facilities and 0.0% of non-accepting facilities; P=0.009) lifestyle guidance categories were significantly more frequently selected by accepting facilities. Non-accepting facilities were significantly more likely to select “explanation of the need to visit a medical institution” (55.3% of accepting facilities and 80.0% of non-accepting facilities; P=0.020) and “guidance on the prevention of infectious diseases” (12.6% of accepting facilities and 32.0% of non-accepting facilities; P=0.012; Figure 4).

Lifestyle guidance in outpatient rehabilitation (top 5 answers). Accepting facilities are for patients with heart failure (HF) only, whereas non-accepting facilities are for patients with diseases other than HF. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 between accepting and non-accepting facilities. HF, heart failure; LTCI, Long‐Term Care Insurance.

Reasons for difficulty in currently accepting HF patients, as well as plans for the future acceptance of HF patients, are shown in Figure 5. The most frequent response selected was “no demand for using OR” (64.0%). Regarding plans for future acceptance of patients with HF, the most frequent response was “want to improve and accept the problems in the facility even with the current system” (24.0%). Another response selected was “would consider accepting them if the evidence for patients with HF in OR becomes more complete” (12.0%).

(A) Reasons for not accepting patients with heart failure (HF) and (B) plans for future acceptance (n=25). CHFEJ, Certified Heart Failure Educator of Japan; CR, cardiac rehabilitation; OR, outpatient rehabilitation.

In this survey, we investigated the actual conditions of CR at OR facilities in the Kansai region of Japan. The number of rehabilitation professionals (PT, OT, and speech therapists) and nurses on staff was significantly higher in the accepting than non-accepting facilities. The number of professional staff is determined by facility standards to be allocated in relation to the number of users.13 We believe that the results were affected by the fact that the average number of total daily users per day in non-accepting facilities was less than 30 (92%), which is lower than that in accepting facilities. Patients attending accepting facilities were aged ≥75 years. Our data on patient demographics were generally consistent with data from previous studies.13,16

Content of Rehabilitation ProgramsRegarding electrothermal therapy, neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES), which is part of electrothermal therapy, has been reported to safely improve lower extremity muscle exercise tolerance in patients with chronic HF,21 and is less taxing on the respiratory and circulatory systems than voluntary exercise.22 Hence, NMES is useful in elderly patients. However, we speculate that NMES is not commonly provided to patients with HF because it was significantly less common in accepting facilities.

Moreover, regarding the cool-down, active cool-down has been reported to hasten the recovery of the cardiovascular and respiratory systems.23 The purpose of active cool-down is to slowly decrease the sympathetic tone induced by exercise and prevent a rapid increase in parasympathetic tone, and cool-down is included in the CR program.18 Therefore, electrothermal therapy and cool-down should be incorporated into CR programs for patients with HF.

A significantly higher percentage of non-accepting than accepting facilities reported using muscle strengthening exercise (rubber tube). This finding can be interpreted in terms of how muscle-strengthening exercises were selected, which considered the characteristics of the patients in the present study. Because most patients with HF were classified as NYHA I/II and the degree of independence of disabled “was high classification”, elderly persons in performing activities of daily living, it is reasonable to expect that they have a living level of muscle. Therefore, elderly patients with HF may not consider using rubber tubing, which makes it difficult to adjust exercise intensity. In addition, the rate of orthopedic complications involving the lower extremities was significantly higher at non-accepting than accepting facilities and may, hence, influence the use of rubber tubing. In contrast with rubber tube training, body weight training requires no tools, and machine training, although requiring equipment, allows for easy adjustment of exercise intensity. Therefore, these 2 exercise methods may be preferred over the use of rubber tubing. Facility characteristics (space and equipment) may have also influenced this parameter because there were significant differences in facility scales.

Risk ManagementIn terms of factors considered when managing risk, “heart rate”, “blood pressure”, “shortness of breath”, and “fatigue/weariness” were most frequently selected, and this is generally consistent with the findings of a previous study,16 wherein the risk was determined by evaluating vital signs. The responses of “arrhythmia”, “oxygen saturation (SpO2)”, “palpitations”, and “chest pressure/chest pain” were significantly higher in accepting facilities (P<0.05). These results are a good reflection of risk management in patients with HF based on current guidelines,14,18 revealing that risk is appropriately managed during rehabilitation. Responses of “lightheadedness” and “lower limb pain (claudication, muscle/joint pain)” were significantly higher in non-accepting facilities (P<0.05). Our data showed that patients at non-accepting facilities were significantly more likely to have neuromuscular diseases and orthopedic conditions (lower extremities). According to these results, patients with HF who visit OR facilities have high activities of daily living capacity.

Exercise LoadIndicators of exercise load during rehabilitation are shown in Figure 3. The most common indicator of exercise load selected was “subjective symptoms” in both accepting and non-accepting facilities. Conversely, “Karvonen formula” and “results of 6-min walk test” were selected less frequently as indicators of exercise load. The reasons for this are assumed to include both patient and facility characteristics. For example, some patients may have had atrial fibrillation, and the staffing standards of OR facilities do not allow enough time for highly individualized assessments, such as the 6-min walk test, because each therapist is responsible for multiple patients.13 However, because the Karvonen method and the 6-min walk test are major assessments in CR,18 their use in clinical practice is expected to increase in the future.

Responses selecting “test results on the medical information form” and “talk test” were significantly higher in accepting than non-accepting facilities (P<0.05). These results suggest that accepting facilities are assessing patients with HF, including taking into account information that is only available in the medical institution, and are providing appropriate exercise therapy. The talk test is a valid, reliable, practical, and inexpensive tool for prescribing and monitoring exercise intensity in patients with cardiovascular disease, including atrial fibrillation.24 Although subjective symptoms can be easily assessed to risk stratify each patient appropriately, they can be influenced by a subject’s motivation and personality, and some elderly patients are more patient and not complain of symptoms.

Lifestyle Guidance“Guidance on exercise and activity level” was the most common lifestyle guidance for patients in both accepting and non-accepting facilities. Because 80% of all patients were over 80 years of age, we believe that this was to prevent frailly.25,26 “Salt intake” and “smoking cessation” as lifestyle guidance for patients with HF were also frequently selected. However, the selection of “explanation of the need to visit a medical institution” and “guidance on the prevention of infectious diseases” was significantly lower in accepting facilities (P<0.05). As mentioned above, the elderly tend to be more patient with their symptoms and the elderly tend to be more patient and not complain of their symptoms, so it is necessary to help them understand the need to seek medical attention. In addition, acute exacerbations due to infections are often observed.15

Reasons for Difficulty in Accepting and Plans for Future Acceptance of Patients With HFThe reason for not accepting patients with HF was a lack of demand for the OR service. Many responses were positive regarding implementing future plans to accept patients with HF. Conversely, some respondents had problems dealing with cardiovascular diseases and asked for evidence of the efficacy of CR at OR facilities. Continued accumulation of evidence in conjunction with an increase in the number of accepting facilities is desirable.

In summary, this survey emphasizes the benefit of CR at OR facilities using LTCI systems for patients with HF. It is important to ensure seamless collaboration between OR facilities and medical institutions because more than 75% of the accepting facilities in our survey have a medical institution attached to them. Because the prognosis of patients differs greatly between Class I/II and III/IV,27 we believe that maintaining NYHA Class I and II, as in the present study population, will lead to the prevention of rehospitalization. A multidisciplinary approach to patients with HF contributes to the prevention of hospitalization due to HF.7,28 In the future, an environment should be created in which CR can be provided to the elderly with HF through OR facilities in each region, including the coordination of medical and nursing care among facilities. However, the response rate in this study was low; therefore, we conducted an additional investigation on non-responding facilities using the Publication System for Long-Term Care Service Information to ascertain the cause of the low response rate (accessed December 3, 2022). Information on responding and non-responding facilities is provided in the Supplementary Table. We collected information from 1,022 non-responding facilities after excluding 236, including 3 with duplicate registrations, 71 deletions of registration, and 162 responding facilities with verified addresses out of 184 responding facilities. However, data from non-responding facilities may include those from 22 responding facilities with unidentified addresses. A comparison of the results showed that significantly more non-responding facilities were located in Wakayama. In terms of facility of operation, significantly more non-responding facilities were in geriatric health services facilities. These results support our hypothesis of low recognition of CR. Wakayama ranks 44th in Japan in the number of institutes offering CR, the lowest in the Kansai region, and does not have a supply of CR.29 The fact that significantly more OR facilities are located in long-term healthcare facilities with a different environment from that of medical care may impact the diffusion and implementation of CR. For these reasons, we consider that the current low recognition of CR from the nursing care domains may have led to a lack of interest in this survey and a lower response rate this time. Therefore, we believe it is necessary to conduct further surveys that include other prefectures in the future.

Study LimitationsThis study has several limitations. First, regarding the response rate (only 14.8%), it is easily expected that CR at OR facilities is covered by the LTCI; however, due to the low prevalence of outpatient CR in medical institutions in Japan, this is not always the case.8 In addition, it is possible that many facilities did not respond to this survey because it was specific to HF and many OR facilities take care of patients with various diseases.13 Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic may have played a role. Thus, the characteristics of facilities may have been influenced by the response rate, and the results could have been overestimated. Second, there were large differences in facility backgrounds between the responding and non-responding groups, and the data on responding facilities was not verified onsite. Therefore, it is difficult to generalize the study results. Third, we did not elaborate on the clinical information of our patient population with HF, including ejection fraction, medication regimens, and history of hospitalization for HF.

This survey revealed the actual conditions of CR for patients with HF attending OR facilities. The rehabilitation regimens for elderly patients with HF in OR facilities mainly included exercise therapy to maintain and improve activities of daily living and basic movement practices. Risk management and lifestyle guidance specific to HF were generally appropriate compared with those for other diseases. The present results show the possibility that outpatient CR can be performed for elderly patients with HF in other than medical insurance.

The authors acknowledge the 184 OR facilities in the Kansai region (6 prefectures) of Japan who completed this survey.

This survey received a grant from the Osaka Gas Group Welfare Foundation 2019.

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

The Ethics Committee of Hyogo College of Medicine approved this survey (No. 3877).

The deidentified participant data will not be shared.

Please find supplementary file(s);

https://doi.org/10.1253/circrep.CR-22-0102