2022 Volume 4 Issue 1 Article ID: 2022-0013-OA

2022 Volume 4 Issue 1 Article ID: 2022-0013-OA

Objective: The aim of this study was to examine the occurrence of Cognitive Attentional Syndrome (CAS) in the Hong Kong Chinese population with depression and to assess the psychometric properties of the translated Traditional Chinese version of the CAS-1 questionnaire. Method: The English version of the CAS-1 questionnaire was translated into Traditional Chinese for this study. Study participants with (N=64) and without (N=64) depression completed the Chinese version of the CAS-1 and the psychometric properties assessed. Results: The internal consistency of the total CAS-1 scores (α=0.704), metacognitive strategies (α=0.789) and metacognitive belief subscales (α=0.716) of the translated Chinese CAS-1 were found to be statistically acceptable. ANCOVA indicated a statistically significant difference between participants with depression and those without depression in CAS-1 total scores (F=4.574, p<0.035) and CAS-1 metacognitive strategies subscale (F=46.615, p<0.0001), treating education level and sex as covariates. Conclusion: The results support the use of the Traditional Chinese version of the CAS-1 questionnaire in clinical settings. In addition, the findings provide the first empirical evidence of the existence of CAS in Hong Kong people with depression.

Major depressive disorder (MDD or “depression”) is a common psychological disorder, affecting more than 260 million people worldwide1). From 10–15% of the population is estimated to experience depression at some point in their lifetime — it has been viewed as one of the most prevalent, and particularly comorbid, psychiatric disorders2). MDD is known as a risk factor for a range of poor coping behaviors and is estimated to be the 2nd leading cause of disease in 2020. This means that the assessment and treatment of MDD is an urgent issue of public health concern3,4).

An advocated remedy for depression is cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and a wide variety of clinical trials have assessed its effectiveness5). However, after CBT treatment, only 40–58% of patients recover6), and of those, relapse rates range from 40–60% within a 2-year period7,8). These indicate major limitations on the treatment efficacy of CBT.

Metacognitive Therapy (MCT) is among the so-called “third wave” of psychotherapies. The key theoretical background contributing to MCT is that the processing responsible for the development and maintenance of a wide range of mood disorders is disordered metacognition. Specifically, MCT proposes that people with MDD have a repetitive and brooding quality to their thinking pattern that is difficult to control. MCT asserts the idea that the intervention should be aimed at the metacognitive level, without calling into question the content of any negative automatic thoughts or typical schemas.

The Self-Regulatory Executive Function model, which is the foundation model of MCT articulates this idea9,10,11). The core principle of MCT is that psychological disorders are linked to the activation of a particular toxic style of thinking called the Cognitive Attentional Syndrome (CAS). CAS consists of a pervasive thinking style that includes worry or rumination, attentional focusing on the threat, and unhelpful coping behaviors that backfire (e.g., reassurance-seeking, avoidance, substance use). In this metacognitive theory of psychological disorder, psychopathology is determined by maladaptive metacognitive beliefs (beliefs about thinking) and an associated persistent negative thinking style. MCT considers this problematic inner state as highly related to some detrimental processes indicated in the characteristics of CAS, and the therapist should focus on removing the CAS. Hence, the meaning and the impact of each of the components of CAS on one’s emotional regulation should be well understood.

There are generally two ways of assessing CAS. The first one is based on the ‘A-M-C’ (antecedent-meta-beliefs-consequences) formulation, applying a generic metacognitive model for many types of psychological disorders. The therapist acquires a necessary impression of the details of the CAS, meta-beliefs, and symptoms using the A-M-C model as a blueprint.

Another way of detecting or assessing CAS is by using measurement scales and questionnaires. The first English adaptation of the CAS-1 questionnaire was used as a clinical device for evaluating and observing cognitive attentional syndrome and fundamental positive and negative metacognitive beliefs during treatment12). A few clinical studies have utilized the CAS-1 to assess and screen metacognitive strategies and beliefs. For example, for social anxiety disorder, Nordahl and Wells (2018) utilized the CAS-1 to screen changes in worry/rumination and threat-monitoring in MCT13). Another study used the CAS-1 when investigating in-person connections and altering mechanisms in treating patients with resistant anxiety disorders in treatment14). Together, these investigations show that the CAS-1 questionnaire is capable of identifying treatment impacts, while its measurements seem to anticipate relevant results.

According to new research, the already high prevalence of depression in Hong Kong is worsening. Probable depression is more than five times higher than it was before 2014 and has doubled since the 2014 Occupy Central Movement15). In a study examining the Depression and Anxiety in Hong Kong during the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, 25.4% reported that their mental health had deteriorated since the pandemic16). As the personal, social, and economic burden of depression is recognized as significant, the development of enhanced treatments (i.e., MCT) for depression is essential.

The aim of this cross-sectional study was to determine if CAS exists in the section of the Hong Kong population that has depression - the first study on CAS in Chinese culture. To do this, we translated the English version of the CAS-1 questionnaire into traditional Chinese, and this study also assessed the validity of the Chinese-language version of the CAS-1 questionnaire.

Sixty-four people with depression were recruited from the Common Mental Disorder Clinic, general adult outpatient clinics in Hospital Authority institutions, or from private psychiatry clinics in Hong Kong. Patients with MDD, either single episode or recurrent, and outpatients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria were recruited by a medical case officer. The inclusion criteria were: (1) a diagnosis of MDD in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual version 5 or diagnoses according to the International Classification of Diseases, version 10 (F33.0–33.9); (2) able to read and speak Cantonese; and (3) able to give informed consent, as assessed by a medical case officer. Another group, consisting of 64 healthy control participants with no history of depressive disorders, was recruited. This control group included occupational therapists and staff members from general hospitals or private psychiatry clinics and their relatives. The exclusion criteria for both groups were: (1) mental instability; (2) mental retardation; (3) presence of neurological disorders; or (4) a history of substance abuse.

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the local hospital review board and the human subjects ethics subcommittee of The Hong Kong Polytechnic University. Before data collection, the nature of the study was described to the participants, and their informed consent was obtained (Appendix 1). The participants were also made aware that data collected would be confidential, and that they were free to withdraw from the study at any time.

Sample-size estimationA medium effect size difference of 0.5 was assumed for this cross-sectional study. With 80% power and a two-tailed p-value set at 0.05, 128 participants in total (64 in each group) were required. To allow for spoiled measures and incomplete data recruiting, 70 per group (140 in total) would have been preferable.

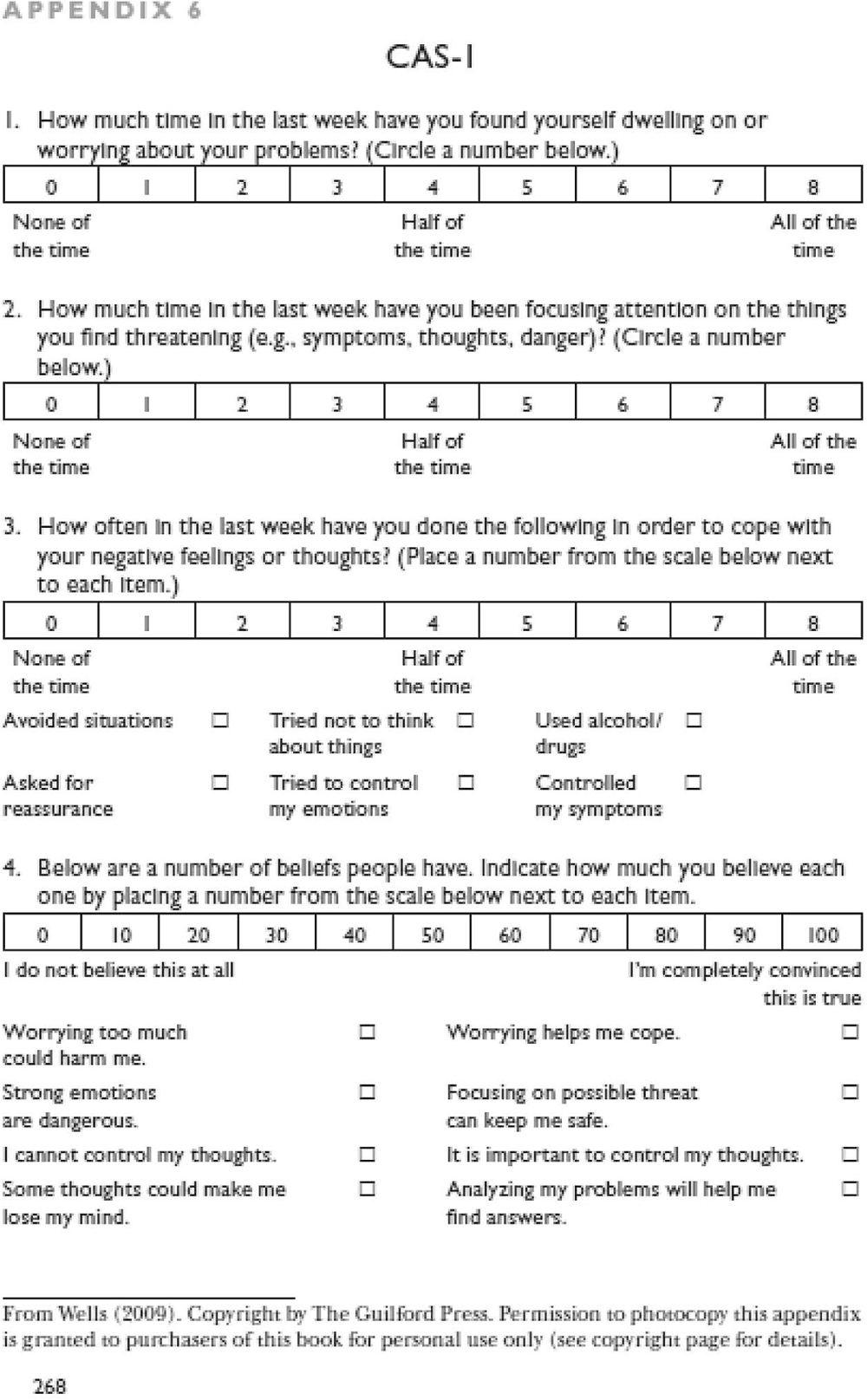

Measures 1. CAS-1– Original English version (Appendix 2)The CAS-1 (Wells, 2009) is a self-reported questionnaire of 16 items measuring four dimensions: (1) worry/rumination, (2) threat monitoring, (3) behaviors to cope with negative feelings, and (4) metacognitive beliefs. The first two items assessed the amount of time spent dwelling on problems and focusing on threat. The following six items asked about the frequency of mal-adaptive strategies used to cope with negative thoughts or feelings (e.g., ‘having tried not to think about things’). The last eight items ask for ratings across a range of metacognitive beliefs. These beliefs are broken down into negative beliefs and positive beliefs. The total CAS-1 scale has shown good internal consistency in previous studies17,18,19).

2. Depression Anxiety and Stress Scales (DASS-21): Chinese version (Appendix 3)The DASS-21 is a 21-point measure that uses three 7-point scales to assess symptoms of depression, anxiety and stress. Responses are given on a scale of 0–3. Numerous studies have shown that the psychometric properties of the DASS are positive20,21,22,23). The Chinese version of the DASS-21 scale24) adopted in this study showed significant differentiation between the depression, anxiety, and stress-negative emotional syndromes. In this study, only the 7 items related to depression were used.

3. Ruminative Response Scale: Chinese version (RRS-C) (Appendix 4)The original Ruminative Response Scale (RRS) is used to assess the ruminative response intensity to depressed mood. The items contain two types of patterns: ‘self-focused’ (e.g., thinking ‘Why am I always reacting this way?’), and ‘symptom-focused’ (thinking about how difficult it is to focus). The present study adopted the Chinese version of RRS (RRS-C) developed in Taiwan that contains 22 items, each accompanied by a scale from 1 (nearly never) to 4 (nearly always). The items contain three types of factors: (1) ‘symptom-based rumination, (2) ‘isolation/introspection’, and (3) ‘analysis for understanding’. The first two are broad factors that have been linked with the Beck’s Depression Inventory score25).

4. Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ): Chinese version (Appendix 5)The Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ) is a measure of worry phenomena, and it has been shown to be valid for cross-cultural populations26). It has 16 items, and each item is rated on a scale from 1 (‘not at all typical of me’) to 5 (‘very characteristic of me’). Eleven items are written in the direction of pathological anxiety, with higher scores indicating higher levels of anxiety (e.g., ‘I can’t stop when I start to worry’), while the remaining five items are written to indicate that anxiety is not an issue, with higher scores indicating less anxiety (e.g., ‘I never worry about anything’). The Chinese version of the PSWQ developed by Zhong et al. (2009) shows good internal consistency as well as convergent and discriminating validity26).

5. Metacognitions Questionnaire-30 (MCQ-30): Chinese version (Appendix 6)In the metacognitive model of psychological disorders, the metacognitions questionnaire (MCQ) measures individual differences in a selection of tendencies considered important for metacognitive beliefs, judgements, and monitoring. The MCQ-30 contains six items for each of the following metacognition dimensions: MCQ1 – Cognitive trust; MCQ2 – Positive concerns; MCQ3 – Cognitive self-consciousness; MCQ4 – Negative beliefs about uncontrollable thoughts and associated dangers; MCQ5 – The need to control thoughts and negative beliefs about the consequences of thoughts.

Translation process for the CAS-1 questionnaireA repeated forward–backwards translation procedure was applied27) to translate the CAS-1 from English into Traditional Chinese. The forward translation was translated into Traditional Chinese by one professional translator from the original language. The translated version was then independently back-translated (i.e., translated from Traditional Chinese back into English) by an experienced psychiatrist who lacked knowledge about the concepts of CAS and MCT. Afterwards, the translated CAS-1 was sent back to the original author to review and comment on whether there was any distortion of the original meanings after the back-translation.

A two-person focus group discussion was conducted by a content expert in CAS (a principal investigator) and an expert with research experience in the field (a professor of rehabilitation). Misunderstandings or unclear wording in the initial translations were revealed in the expert panel discussion. Afterwards, the instrument was tested on a small group of intended respondents. After filling in the translated questionnaire, the respondents were asked (verbally by an interviewer) to elaborate on what they understood by each questionnaire item and the meaning of each corresponding response. Item analysis and interviews with this small participant group resulted in the further amendment of the instrument. After the translated questionnaire items pass through preliminary pilot testing and subsequent revisions, a final version of the questionnaire was then established with a format change in the scoring part of question three for items 3 to 8 (Appendix 7).

Cross-sectional studyA one-off cross-sectional assessment session was conducted across the two groups of study participants. The control group completed only the translated CAS-1 questionnaire.

Statistical proceduresThe data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), Version 26 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). Before conducting the analyses, the data were screened for missing values, outliers, and normality. There was one outlier found in the CAS-1 total scores in depression participants. As most parametric statistics like correlations are sensitive to outliers, all statistical testing after removing this outlier was conducted to observe if this outlier had a significant impact on the overall statistical significance in Pearson correlation and analysis of covariance (ANCOVA)28). We found no significant change in statistical significance in the zero-order correlation testing or ANCOVA with or without this outlier.

The participants’ demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1. The mean age for the participants with depression was 49.6 years (standard deviation [SD], 15.0), and without depression 45.7 years (SD, 12.8). This was not a statistically significant difference in age. Fifty-three (83%) of the participants with depression were female and 42 (66%) of the participants without depression were female. This difference between the sexes of the two groups was statistically significant (Chi-Square=4.940, p=0.026). Additionally, the control group had a higher education level than the depression group – 52% versus 6% had an undergraduate degree or above. Sex and education level may become the covariates. The main reason is that there is no random assignment for the two groups due to different conditions required (i.e., depression versus control). There was also no manipulation in the case of recruitment in control group participants. The sampling in the depression group was convenience sampling (i.e., referred by a psychiatrist). ANCOVA was adopted for the baseline group differences that exist on the dependent variable. Using this method, the means of the dependent variable were adjusted in an attempt to adjust for individual differences.

| Group | Variance | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | Control | ||||||

| Count | Mean | Variance | Count | Mean | |||

| Sex | Male | 11 | 22 | ||||

| Female | 53 | 42 | |||||

| Age (years) | 49.6 | 223.504 | 45.7 | 163.768 | |||

| Education | No formal education | 3 | 0 | ||||

| Primary level | 15 | 3 | |||||

| Secondary level | 35 | 23 | |||||

| Higher diploma | 7 | 5 | |||||

| Degree or above | 4 | 33 | |||||

ANCOVA was used to compare the mean of total scores and two subscales of the CAS-1 for the depression group and healthy group. Both education level and sex were used as the covariate. There was a statistically significant difference between depression group participants and healthy participants (F=4.574, p<0.034) in CAS-1 total scores (Table 2). A similar result was shown when comparing the Metacognitive strategies (F=46.615, p<0.0001) between the two groups (Table 3). Metacognitive strategies have the highest variance explained by the group/depression effect with 36.6% compared to only 5.8% in CAS-1 total scores.

| Source | Type III Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | Partial Eta Squared | Noncent. Parameter | Observed Power‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corrected Model | 131.833† | 3 | 43.944 | 2.501 | .063 | .058 | 7.504 | .608 |

| Intercept | 1072.656 | 1 | 1072.656 | 61.055 | .000 | .334 | 61.055 | 1.000 |

| Education_Nominal | 5.005 | 1 | 5.005 | .285 | .594 | .002 | .285 | .083 |

| Sex | .609 | 1 | .609 | .035 | .853 | .000 | .035 | .054 |

| Group | 80.363 | 1 | 80.363 | 4.574 | .034 | .036 | 4.574 | .564 |

| Error | 2143.382 | 122 | 17.569 | |||||

| Total | 32383.000 | 126 | ||||||

| Corrected Total | 2275.215 | 125 |

| Source | Type III Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | Partial Eta Squared | Noncent. Parameter | Observed Power‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corrected Model | 116.088† | 3 | 38.696 | 23.817 | .000 | .366 | 71.452 | 1.000 |

| Intercept | 117.255 | 1 | 117.255 | 72.170 | .000 | .368 | 72.170 | 1.000 |

| Education Nominal | 3.154 | 1 | 3.154 | 1.941 | .166 | .015 | 1.941 | .282 |

| Sex | .001 | 1 | .001 | .001 | .977 | .000 | .001 | .050 |

| Group | 75.735 | 1 | 75.735 | 46.615 | .000 | .273 | 46.615 | 1.000 |

| Error | 201.463 | 124 | 1.625 | |||||

| Total | 3201.000 | 128 | ||||||

| Corrected Total | 317.551 | 127 |

Dependent Variable: CASS Transformed

The Cronbach Alpha reliability coefficient of all 16 items in CAS-1 was 0.704. Also, this proportion was 0.789 for the first eight items (Metacognitive Strategies) and 0.716 for the last eight items (Metacognitive Beliefs). These results showed that the internal consistency of CAS-1 was acceptable in clinical samples.

Structural validityExploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was adopted in the factor analysis which evaluated the structural validity of the translated Traditional Chinese version of the CAS-1 questionnaire.

A principal components analysis was carried out on the correlation matrix of the 16 items of the translated CAS-1 version. This study’s exploratory approach was justified by the extraction of factors that had their own values greater than or equal to 1.0. The factor analysis results indicated that the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin sampling adequacy measure was at an acceptable level of 0.702, and Bartlett’s sphericity test was 329.595, p<0.0001, indicating that all the correlations tested at the same time differed significantly from zero. For the rotated component matrix, all items with a value of less than 0.4 or represented by more than one factor were removed one by one to finally reach a version with 5 factors and 14 items. The first three factors consisted of three items or more while factors 4 and 5 only consisted of two items. Under this circumference, only the first three factors should be retained.

Further scales classification in data analysisThe EFA discovered a three-factor structure of the translated questionnaire. The items belonging to Factors I, II and III were further denoted by CASS2, CASNEG and CASPOS as three subscales respectively and used to conducted convergent and concurrent validity testing.

Convergent validityThe convergent validity of the CAS-1 was tested by correlating the total scores and three subscales with related concepts: Chinese versions of RRS, PSWQ, and MCQ-30. The mean score in the clinical sample (N=64) was 516.94 (SD, 122.75) on the CAS-1, 21.80 (SD, 12.03) on the RRS, 52.92 (SD, 14.80) on the PSWQ, and 66.66 (SD, 15.79) on the MCQ-30. As shown, the CAS-1 total scores shared significant positive correlations with all the other variables. The strongest relationship was found between CAS-1 total scores and PSWQ (r=0.429, p<0.0001), which measures pathological worry (Table 5).

| CAST | CASS | CASM | RRS | RRSSYM | RRSISO | PSWQ | MCQ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAST | Pearson Correlation | 1 | .601** | .997** | .375** | .392** | .200 | .429** | .372** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .000 | .000 | .002 | .001 | .113 | .000 | .002 | ||

| N | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | |

| CASS | Pearson Correlation | .601** | 1 | .542** | .519** | .505** | .434** | .583** | .508** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | ||

| N | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | |

| CASM | Pearson Correlation | .997** | .542** | 1 | .348** | .366** | .171 | .399** | .345** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .000 | .000 | .005 | .003 | .176 | .001 | .005 | ||

| N | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | |

| RRS | Pearson Correlation | .375** | .519** | .348** | 1 | .968** | .825** | .650** | .629** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .002 | .000 | .005 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | ||

| N | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | |

| RRSSYM | Pearson Correlation | .392** | .505** | .366** | .968** | 1 | .705** | .637** | .574** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .001 | .000 | .003 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | ||

| N | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | |

| RRSISO | Pearson Correlation | .200 | .434** | .171 | .825** | .705** | 1 | .532** | .554** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .113 | .000 | .176 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | ||

| N | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | |

| PSWQ | Pearson Correlation | .429** | .583** | .399** | .650** | .637** | .532** | 1 | .656** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .000 | .000 | .001 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | ||

| N | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | |

| MCQ | Pearson Correlation | .372** | .508** | .345** | .629** | .574** | .554** | .656** | 1 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .002 | .000 | .005 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | ||

| N | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 |

CASM, Cognitive Attentional Syndrome-1 metacognition subscale; CASS, Cognitive Attentional Syndrome-1 strategy subscale; CAST, Cognitive Attentional Syndrome-1 total score; MCQ-30, Metacognitions Questionnaire-30 total score; PSWQ, Penn State Worry Questionnaire; RRS, Ruminative Response Scale; RRSSYM, Ruminative Response Scale ‘symptom-based rumination’ items; RRSISO, Ruminative Response Scale ‘isolation/introspection’ items.

For a more detailed examination about the concept embedded in the construct of CAS with a similar concept measured in other instruments, the three subscales of CAS-1 devised by EFA, the ‘Metacognitive Strategies’, ‘Negative meta-beliefs’ and ‘Positive meta-beliefs’ were also tested by correlating with relevant measurements. A statistically significant moderate positive relationship was found between ‘metacognitive strategies’ subscale and all other variables, where all Pearson Correlation coefficients were 0.5 or higher. Correlations coefficients were calculated between the other two subscales of the CAS-1 (‘Negative Meta-beliefs’ and ‘Positive Meta-beliefs’) and MCQ-30 – a similar tool. There were also statistically significant positive correlations between MCQ-30 total scores and these CAS-1 subscales (Pearson correlation coefficients 0.3, p<0.05 for both).

Concurrent validityPearson’s correlation analysis was used to assess the relationship between CAS-1 total scores and the three subscales and each of the seven DASS-21 depressive items (Table 6). The CASS2 showed a statistically significant correlation with all the depressive items in DASS-21. The strongest relationships were shown between CASS2 and DASS-21 Item 13, ‘I felt down-hearted and blue’, and Item 3, ‘I couldn’t seem to experience any positive feeling at all’.

| CASS | DASSQ3 | DASSQ5 | DASSQ10 | DASSQ13 | DASSQ16 | DASSQ17 | DASSQ21 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CASS | Pearson Correlation | 1 | .445** | .363** | .337** | .586** | .301* | .327** | .260* |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .000 | .003 | .006 | .000 | .016 | .008 | .038 | ||

| N | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | |

| DASSQ3 | Pearson Correlation | .445** | 1 | .463** | .340** | .656** | .381** | .334** | .260* |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .000 | .000 | .006 | .000 | .002 | .007 | .038 | ||

| N | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | |

| DASSQ5 | Pearson Correlation | .363** | .463** | 1 | .405** | .445** | .494** | .156 | .105 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .003 | .000 | .001 | .000 | .000 | .219 | .407 | ||

| N | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | |

| DASSQ10 | Pearson Correlation | .337** | .340** | .405** | 1 | .419** | .565** | .214 | .395** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .006 | .006 | .001 | .001 | .000 | .089 | .001 | ||

| N | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | |

| DASSQ13 | Pearson Correlation | .586** | .656** | .445** | .419** | 1 | .469** | .547** | .340** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .000 | .000 | .000 | .001 | .000 | .000 | .006 | ||

| N | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | |

| DASSQ16 | Pearson Correlation | .301* | .381** | .494** | .565** | .469** | 1 | .438** | .528** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .016 | .002 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | ||

| N | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | |

| DASSQ17 | Pearson Correlation | .327** | .334** | .156 | .214 | .547** | .438** | 1 | .707** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .008 | .007 | .219 | .089 | .000 | .000 | .000 | ||

| N | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | |

| DASSQ21 | Pearson Correlation | .260* | .260* | .105 | .395** | .340** | .528** | .707** | 1 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .038 | .038 | .407 | .001 | .006 | .000 | .000 | ||

| N | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 |

CAS, Cognitive Attentional Syndrome-1 strategy subscale; DASSQ, Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale Questionnaire.

The depression group reported a higher mean CAS-1 total score (517; SD, 123 vs. 445; SD, 141), Metacognitive Strategies subscale (32; SD, 11 vs. 16; SD, 12) and Metacognitive Belief subscale (485; SD, 117 vs. 429; SD, 139) than the healthy group. This pattern also held true for all the individual CAS-1 items (Table 4).

| Variable | N | Depression | Control | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean | SD | variance | mean | SD | variance | ||

| CAS Q1 | 64 | 4.94 | 1.89 | 3.58 | 3.17 | 2.10 | 4.40 |

| How much time in the last week have you found yourself dwelling on or worrying about your problems? | |||||||

| CAS Q2 | 64 | 4.86 | 2.09 | 4.38 | 2.22 | 2.00 | 3.98 |

| How much time in the last week have you been focusing attention on the things you find threatening (e.g., symptoms, thoughts, danger)? | |||||||

| CAS Q31 | 64 | 3.91 | 2.58 | 6.66 | 1.52 | 2.28 | 5.21 |

| How often in the last week have you done the following in order to cope with your negative feelings or thoughts? (Avoided situations) | |||||||

| CAS Q32 | 64 | 4.27 | 2.10 | 4.42 | 2.05 | 2.32 | 5.38 |

| How often in the last week have you done the following in order to cope with your negative feelings or thoughts? (Asked for reassurance) | |||||||

| CAS Q33 | 64 | 4.63 | 1.95 | 3.79 | 2.13 | 2.19 | 4.81 |

| How often in the last week have you done the following in order to cope with your negative feelings or thoughts? (Tried not to think about things) | |||||||

| CAS Q34 | 64 | 4.44 | 2.00 | 4.00 | 2.73 | 2.27 | 5.15 |

| How often in the last week have you done the following in order to cope with your negative feelings or thoughts? (Tried to control my emotions) | |||||||

| CAS Q35 | 64 | 1.64 | 1.80 | 3.25 | 0.36 | 1.10 | 1.22 |

| How often in the last week have you done the following in order to cope with your negative feelings or thoughts? (Used alcohol/drugs) | |||||||

| CAS Q36 | 64 | 3.58 | 2.01 | 4.03 | 1.47 | 2.35 | 5.52 |

| How often in the last week have you done the following in order to cope with your negative feelings or thoughts? (Controlled my symptoms) | |||||||

| CAS Q41 | 64 | 67.19 | 27.92 | 779.3 | 68.3 | 27.8 | 773.2 |

| How much do you believe each of the following beliefs people have? (Worrying too much could harm me) | |||||||

| CAS Q42 | 64 | 65.47 | 27.83 | 774.4 | 64.7 | 30.3 | 917.4 |

| How much do you believe each of the following beliefs people have? (Strong emotions are dangerous) | |||||||

| CAS Q43 | 64 | 60.63 | 26.78 | 717.1 | 27.3 | 24.6 | 607.1 |

| How much do you believe each of the following beliefs people have? (I cannot control my thoughts) | |||||||

| CAS Q44 | 64 | 51.88 | 32.21 | 1037.7 | 36.4 | 30.9 | 956.7 |

| How much do you believe each of the following beliefs people have? (Some thoughts could make me lost my mind) | |||||||

| CAS Q45 | 64 | 44.69 | 17.99 | 323.7 | 27.5 | 27.5 | 758.7 |

| How much do you believe each of the following beliefs people have? (Worrying helps me cope) | |||||||

| CAS Q46 | 64 | 55.47 | 22.46 | 504.5 | 29.5 | 29.5 | 873.0 |

| How much do you believe each of the following beliefs people have? (Focusing on possible threat can keep me safe) | |||||||

| CAS Q47 | 64 | 72.97 | 21.80 | 475.2 | 25.4 | 25.4 | 645.4 |

| How much do you believe each of the following beliefs people have? (It is important to control my thoughts) | |||||||

| CAS Q48 | 64 | 66.41 | 21.92 | 480.5 | 23.4 | 23.4 | 548.6 |

| How much do you believe each of the following beliefs people have? (Analyzing my problems will help me find answers) | |||||||

CAS, cognitive attentional syndrome; SD, standard deviation.

The present study is the first to focus on the construct of Cognitive Attentional Syndrome in people with depression in Asia. The CAS-1 questionnaire was examined by testing its correlation with similar concepts in other established measurements and found to be positively correlated with all measures of depressive symptoms, ruminative response to depressed mood, pathological worry, and metacognitive beliefs. The metacognitive strategies subscale also positively correlated with all the measures mentioned above.

This study provided a preliminary version of a translated Chinese version of the CAS-1 questionnaire, which has acceptable internal consistency and validity. Some cultural differences were found throughout the translation and validation process in terms of understanding and responding to the related concept. For instance, many respondents regarded ‘Worry’ as ‘Problem-solving’ or focusing on thinking of a solution to their problems. Worry also means concerning and paying attention to something important and difficulties they are encountered. However, the original definition of worry in CAS-1 is about anticipating potential danger, threat, and failure, which is a future-oriented thinking process.

For rumination, some respondents thought that it is about memory recall on past negative events with personal significance or dwelling on finding solutions to stressful life events. In CAS, rumination means finding an answer to negative thoughts or emotions with excessive self-focused attention. For the threat-monitoring strategies, some respondents thought that there is a need to apply different fashion of strategies to monitor different threats. The life examples of “threats” included “extramarital affairs”, “traffic accidents”, “personal development of their children” and “loneliness or other negative emotions”. They thought that threat-monitoring is an inherited response that they are supposed to do. Some also mentioned the protective nature of such methods that they need to use to deal with threats for the purpose of keeping a secure feeling. However, many of them were not aware of the internalized nature of the threat and, most importantly, the monitoring did not bring them a more secure feeling but an increased sense of threat. Besides, many of the respondents needed time and verbal prompting to understand the proposed meaning of the metacognitive strategies during the cross-sectional questionnaire filling. Also, all of them were unfamiliar with or had never even heard of the concept of CAS during their course of illness.

Analysis of covariance provided evidence that the level of metacognitive strategies (items 1–8) adopted by people with depression is significantly higher than that of healthy participants. However, the difference between clinical and non-clinical groups on the CAS-1 Metacognitive Belief subscale was not statistically significant. Nevertheless, the CAS-1 total score, which indicated the syndrome level between the two groups, reached a statistically significant level. This pattern may indicate that the differences in the level of adopting metacognitive strategies outweighed the differences in meta-beliefs between groups so that the overall syndrome level still differed significantly.

The ANCOVA testing may help support the use of the translated CAS-1 questionnaire in clinical settings to serve as a measure used to assess the recurrent and brooding qualities of thinking and coping style (CAS) among people suspected to have mood disorders. In the depression group, a higher reported time engaged in rumination/worry and threat-monitoring was found indicated by CAS-1 Item 1 (mean 4.94; SD, 1.89) and 2 (mean 4.86; SD, 2.09) than in the healthy control group participants’ Item 1 (mean 3.17; SD, 2.10) and 2 (mean 2.22; SD, 2.00) (Table 4). An exploratory factor analysis found a three-factor structure that may not be similar to the original version of the CAS-1.

The first factor includes items 1, 2, 3.2, and 3.6. These items capture how much time the respondents said they spent in each thought pattern and ‘coped by asking or controlling’. First, it reflects that participants were reporting time-engagement in rumination/worry, threat-monitoring, and adopting unhelpful coping strategies. It also reflects the fact that the participants tended to respond to their problems when they feel sad, blue, or depressed (negative emotions) or when they are moody. Second, although the original author provided similar factors labelled as, for example, ‘extended thinking’, Factor I in our study captures a broader range of coping strategies, such as asking for reassurance and controlling their symptoms, rather than only spending time thinking about problems/threats. Rumination is a key thought pattern found among people with depression in response to negative thoughts or another form of triggers. Other than rumination, another component of CAS is the monitoring of threats.

In depression, it tends to occur in the form of focusing on the depression symptoms and changes in mood. Individuals tend to control their symptoms when closely monitoring them, discovering the manifestation of depressive symptoms (i.e., tiredness and lack of energy). They also monitor mood change and try to seek/ask for reassurance so as to ease the negative effect. Hence, Factor I implicitly captures the concepts of ‘rumination’, ‘threat monitoring’, ‘focusing on symptoms with active control’, and also ‘dealing with mood change by asking for reassurance’. All of these are metacognitive strategies. Hence, Factor I may be optimally labelled as ‘Metacognitive Strategies’.

All items in the second factor — items 4.1) ‘Worrying too much could harm me’, 4.2) ‘Strong emotions are dangerous’ and 4.3) ‘I cannot control my thoughts’ — match the original version of the CAS-1’s ‘Negative meta-beliefs’. It should be of no doubt that the present translated Traditional Chinese version of these three items represents the same meaning. Therefore, Factor II has been named ‘Negative meta-beliefs’. The third factor included items 3.1) ‘Avoided situations’, 4.5) ‘Worrying helps me cope’, and 4.6) ‘Focusing on possible threat can keep me safe’. It covers two of the three ‘positive meta-beliefs’ as labelled in the original version. It added one more item for the unhelpful coping strategy, which captures a sense of avoidance (concerning situations). We could view this as a measure of saving time so as to allow active coping with negative thoughts by worrying and threat-monitoring, which people found advantageous (i.e., positive meta-belief concerns the usefulness or advantages of engaging in such metacognitive strategies) but time-consuming. In summary, for Factor III, ‘Positive meta-beliefs’ is still considered an adequate name.

It may raise concerns about the cultural differences involved in the development of CAS factors. Hence, a further study aiming at a larger sample size should be conducted to establish a more stable and valid factor structure of the translated version of CAS-1. Nevertheless, the CAS-1 can still be constructively divided into three subscales that assess metacognitive strategies in addition to positive and negative metacognitive beliefs. As these factors appear to have acceptable reliability and validity, it is recommended they should be used continuously in clinical settings and research to assess and monitor change in conceptually important metacognitive dimensions during therapy.

One striking point is that the metacognitive beliefs between the clinical group and the non-clinical group were remarkably close — neither clinically nor statistically significantly different. For the healthy population, some may have an increased level of metacognitive belief, which is the driving force behind toxic styles of thinking (i.e., CAS). However, some healthy individuals may have a higher level of education (as shown in this study by the differences between the groups; Table 1), which may lead to more constructive coping strategies to adversity and negative emotions. When there are increased environmental factors or psychosocial stressors, individuals with an increased level of metacognitive beliefs may have a higher risk of developing psychological disorders, which are likely due to the manifestation of the maladaptive metacognitive strategies driven by the meta-beliefs. An example might help explain that the rate of probable depression among the Hong Kong population: in the midst of the latest protests (2019), probable depression was nearly twice the level recorded in 2014 during Occupy Central. According to a University of Hong Kong survey conducted during the extradition bill crisis, nearly one in ten people in Hong Kong was found to have suspected depression, as the city suffered an “epidemic of mental health problems”29). This interpretation may be grounds for the introduction of CAS and metacognitive beliefs to be added to the training curriculum of clinical practitioners. There could also be value in public health education to introduce this idea to citizens, especially as metacognitive beliefs and CAS are new concepts in Asia.

A public health initiative could serve two purposes: the first is to increase the public’s awareness of the negative consequence of high conviction of metacognitive beliefs in a number of maladaptive thinking and behavioral coping strategies, and the second is to offer early intervention, probably by MCT, to reduce CAS and underlying metacognitive beliefs if the individual found early mood disturbance with an assessed high level of CAS and metacognitive beliefs. This, in turn, may serve to add one ‘early warning sign’ to encourage the public to seek early treatment.

If the ‘normal’ public individuals hold a high conviction of metacognitive beliefs, they might likely choose rumination and worry as the main coping strategies to daily challenges and negative thoughts. Many citizens may recall the memory of daily work and review what they did wrong or what were the criticisms given by a boss or colleagues. Many also report insomnia and ruminative thinking before falling asleep. These somehow indicate the manifestation of extended thinking, which is the very core feature of CAS, among the citizens. Brief metacognitive therapy may be also applicable, such as detached mindfulness techniques, when citizens are facing difficulties over their current life. It also serves the purpose of holding the premise that “prevention is better than cure”.

Hong Kong people with depression typically receive CBT, due to the proven therapeutic effect in depression and the long-lasting professional training adopted in Hong Kong for nearly 20 years. However, both clinicians and patients are unaware of the universal thinking habit or patterns and underlying metacognitive beliefs that govern CAS. CBT does not target this meta-level, and patients usually continue CAS even if the CBT was thought to be effective. MCT might be an alternative or additional treatment modality in these cases.

MCT is the only psychotherapy that considers CAS and Metacognitive Beliefs under the psychopathology of psychological disorders. It is also the only treatment that targets the elimination of CAS and the modification of underlying metacognitive beliefs, which helps patients return to ‘normal’ emotional regulation and subsequently recover from the disorders. As such, the healthcare providers in Hong Kong should consider incorporating MCT into clinical practice, both in the public hospitals and private settings, for the sake of patients’ benefit of having better psychotherapy to make a good recovery from depression.

Three limitations were identified in this study: (1) our sample size was small, and therefore, the findings should be cross validated in a larger sample size; (2) there was no control for the length of treatment among the depression participants, so the cases of the syndrome were rather varied in the sample. Further study with control in the length of treatment to establish a more homogenous sample is preferable; and (3) there was no discriminant validity in this study. Further study with discriminant validity testing should be involved, as both convergent and discriminant validity are two important components of construct validity.

Kino C.K. Lam wrote the manuscript and provided data for all tables. Hector W.H. Tsang provided supervision and guidance for KL to conduct all statistical analyses. All authors have reviewed the final manuscript.

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the local hospital review board and the human subjects ethics subcommittee of The Hong Kong Polytechnic University. Before data collection, the nature of the study was described to the participants, and their informed consent was obtained (Appendix 1). The participants were also made aware that data collected would be confidential, and that they were free to withdraw from the study at any time.

There are no conflicts of interest.