2025 Volume 7 Issue 1 Article ID: 2024-0015-FS

2025 Volume 7 Issue 1 Article ID: 2024-0015-FS

Objectives: This study examined the effects of an online group program based on acceptance and commitment therapy for young employees on employee well-being. Methods: Using a single-case A-B design, this study implemented a program that spanned three 90-min sessions among 24 employees of a Japanese company, who were up to 3 years after graduation from university or postgraduate studies. The baseline (times 1–5) phase was conducted across 15 days, followed by the intervention, which was conducted over 16 days. The intervention (times 6–10) phase was conducted over 35 days following session 1. Results: Fourteen participants met the inclusion criteria. A hierarchical Bayesian model indicated that the hypotheses were not supported in terms of the primary outcome of well-being and process outcome of psychological inflexibility of 10 employees because the credible interval included 0 (well-being: expected a posteriori estimation [EAP] 0.22; 95% credible interval, −0.31 to 0.81; Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II: EAP −2.20; 95% credible interval, −5.60 to 1.31). Tau-U for well-being varied from −0.56 to 0.84 among the participants. Similarly, for the secondary outcomes of 13 employees, the hypotheses were not supported for work performance, work engagement, and stress reaction (World Health Organization Health and Work Performance Questionnaire: EAP −0.32; 95% credible interval, −1.22 to 0.57; Utrecht Work Engagement Scale-3: EAP −0.08; 95% credible interval, −0.47 to 0.34; stress reaction: EAP −0.49; 95% credible interval, −3.76 to 2.66). Conclusions: The online group program implemented in this study did not improve employee well-being. Trial registration: The study protocol was registered with the University Hospital Medical Information Network Clinical Trials Registry (ID: UMIN000042912).

Well-being, characterized by life satisfaction, decreases in adolescence, then slightly increases and decreases, once again, in late adulthood1). To promote the maintenance or improvement of well-being in late adulthood, establishing patterns of behavior during occupational life, which constitutes the majority of life, may be beneficial. Thus, providing intervention as early as possible in their occupational lives, that is, as young employees, is considered desirable.

The application of acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) in the workplace is a promising approach for improving employee well-being2). A theoretical model for the usefulness of ACT in the workplace is the goal-related context-sensitivity hypothesis: psychologically flexible people spend less of their limited attentional resources on controlling internal events; instead, they notice and respond more effectively to goal-related opportunities that exist in their situation3,4).

Since Bond and Bunce5) first evaluated ACT as a workplace training program, research that reviews ACT interventions has been steadily accumulating. The latest meta-analysis reports that ACT is an effective intervention for reducing the psychological distress and stress and improving the psychological flexibility and well-being of employees6). Previous studies also demonstrate that high levels of psychological flexibility longitudinally predict better work performance (WP)7,8). However, although a few of these studies included young employees, they did not focus directly on improving the well-being of young employees. In addition, in recent years, findings from online ACT interventions have been accumulating9). Research that focuses on youth has demonstrated improvement in mental health and well-being; however, consensus on the effectiveness of such interventions has not been reached due to methodological issues10). Furthermore, although these reviews are mainly based on research on self-help interventions, the need to conduct online group interventions, instead of face-to-face interventions, has increased in the workplace since the spread of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Therefore, reporting on the effects of such practices while considering their methodological quality is considered to be of empirical value for occupational health.

The current study used a single-case A-B design to examine the effects of an online group program based on ACT for young employees on well-being, WP, work engagement (WE), stress reaction, frequency of valued actions, and psychological inflexibility (PiF). Interest in single-case analysis, particularly single-case experimental designs, is increasing for the following reasons. In addition to the usefulness of single-case A-B designs for the development of reporting guidelines and the ability to apply rigorous statistical methods, the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine considers these designs to be equivalent to level-one evidence in systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials in the case of a randomized N-of-1 trial. Therefore, they enable the conduct of high-quality research even in small populations11,12,13). The single-case methodology is not merely a comparison of scores before and after an intervention but also a visualization of individual outcome trends that can lead to practical suggestions. For this reason, we also adopted a single-case methodology.

We hypothesized that each indicator would exhibit a better trend for each participant after the intervention. This manuscript was written with reference to the Single-Case Reporting guideline In BEhavioural interventions (SCRIBE)14).

The study used a single-case A-B design. The participants concurrently started in the baseline (phase A) and intervention (phase B) phases. To accommodate their work schedules, the program with the same content was repeated on two dates per session. The participants reported to the human resources department on whichever session they preferred, and the human resources department allocated a session by considering the length of service of each participant. No randomization or blinding was conducted. The participants were recruited between February 5 and 8, 2021. Table 1 presents the parts and measurement timing plot. The data underlying this manuscript are available in the Open Science Framework (OSF) (https://osf.io/y7n9r/).

| Time series | Measurement points | Measures | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Time 1 (February 5 through 8, 2021) | (1) (2) (3) (4) (6) | |

| Time 2–5 (February 9 through 19, 2021) | (1) (6) | ||

| Intervention | Session 1 | (February 22 or 24, 2021) | |

| Time 6 (February 25 and 26, 2021) | (1) (6) | ||

| Session 2 | (March 1 or 3, 2021) | ||

| Time 7 (March 4 and 5, 2021) | (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) | ||

| Session 3 | (March 8 or 9, 2021) | ||

| Time 8 (March 11 through 17, 2021) | (1) (5) (6) | ||

| Time 9 (March 18 through 24, 2021) | (1) (5) (6) | ||

| Time 10 (March 25 through 31, 2021) | (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) |

(1) Well-being: primary outcome, (2) work performance: secondary outcome, (3) work engagement: secondary outcome, (4) stress reaction: secondary outcome, (5) frequency of valued actions: secondary outcome, and (6) psychological inflexibility: process outcome.

The study invited 24 employees in Company A within 3 years after university graduation or postgraduate studies, who are typically aged in their mid-20s. Company A belongs to the service sector and focuses on providing mental health care services to companies in Japan. Demographic characteristics, such as the sex and age of participants, were not obtained to prevent the identification of individuals. The program was one of the corporate training programs that the president of Company A tasked the human resources department to plan to train young employees in self-care skills to improve mental health. Therefore, no formal sample size calculation was used. All 24 employees who were targeted for training participated in the program. The inclusion criteria were as follows: participants who agreed to participate at time 1, successfully completed each questionnaire, and participated in all three sessions. No exclusion criteria were established.

InterventionThe intervention was a group program based on ACT for 12 participants per group using Microsoft Teams® video conferencing and consisted of three sessions that each lasted for 90 min. As the training program was for young employees, the intervention was primarily developed with reference to programs based on ACT for employees and youth2,15). Table 2 displays the specific program contents. The implementer of the intervention was the second author (MT), who supervised and translated the Japanese version of Flaxman et al.2) and had experience in delivering self-care education on ACT in several offices. The participants were also invited to join a dedicated community space using Microsoft Viva Engage®, in which they were encouraged to record their home practice and share their observations. All interventions were conducted online, because a state of emergency was in place for Tokyo, where Company A is located, due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

| Session | Elements of the intervention | Contents of the intervention |

|---|---|---|

| Session 1 | Introduction | Overview of the program |

| “Mindful listening” | ||

| The Two-Skills Diagram & “Passengers on the Bus” metaphor | ||

| Values-based action | “Living by the Numbers” exercise | |

| Group discussion | ||

| “Values, Goals, and Actions Worksheet” | ||

| Group discussion | ||

| Summary of the part | ||

| Mindfulness | “Passengers on the Bus” exercise | |

| “Brief Body and Breath Awareness Exercise” | ||

| Group discussion | ||

| Summary of the part | ||

| Home practice | Overview of the home practice | |

| Summary | Summary of the session 1 | |

| Session 2 | Introduction | Overview of the program |

| The Two-Skills Diagram & “Passengers on the Bus” metaphor | ||

| Group discussion (home practice review) | ||

| Values-based action | “Wealth: 5000 trillion yen” exercise | |

| “Values, Goals, and Actions Map” | ||

| “Values, Goals, and Actions Worksheet” | ||

| Summary of the part | ||

| Mindfulness | “Brief Body and Breath Awareness Exercise” | |

| “Capturing Unhelpful Thoughts and Labeling the Mind” | ||

| “Cartoon Voices Technique” | ||

| Group discussion | ||

| Summary of the part | ||

| Home practice | Overview of the home practice | |

| Summary | Summary of the session 2 | |

| Session 3 | Introduction | Overview of the program |

| The Two-Skills Diagram & “Passengers on the Bus” metaphor | ||

| Group discussion (home practice review) | ||

| Mindfulness | “Mindfulness of Breath Practice” | |

| “Physicalizing Exercise” | ||

| Group discussion | ||

| “Raise your hand, thinking you can’t do it” exercise | ||

| Summary of the part | ||

| Values-based action | “Values, Goals, and Actions Worksheet” | |

| Summary | Group discussion | |

| Summary of the program |

The contents of intervention were developed with reference to programs based on acceptance and commitment therapy for employees and youth2,15). Supplementary explanations of the program are available on the Open Science Framework.

Outcome variables were collected through questionnaires via Microsoft Forms®. The participants responded to the same five questions in each questionnaire. Responses were used to create self-generated identification codes for longitudinal data collection with reference to Agley et al16).

Primary outcomeWell-being. The study assessed well-being using the Japan Quality of Life Survey17). Specifically, one question was posed: “All things considered, how satisfied are you with your life as a whole these days?” The item was rated using an 11-point scale ranging from 0 (completely dissatisfied) to 10 (completely satisfied), with high scores indicating high levels of well-being.

Secondary outcomesWork performance. The study examined WP using the World Health Organization Health and Work Performance Questionnaire18,19). It measures three items using an 11-point scale ranging from 0 (worst performance) to 10 (top performance), of which the “How would you rate your overall job performance on the days you worked during the past 4 weeks (28 days)?” was used in the analysis. High scores indicate high levels of WP.

Work engagement. WE was evaluated using the three-item version of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale20,21). The items were rated using a 7-point scale ranging from 0 (never) to 6 (always). High scores indicate high levels of WE.

Stress reaction. The study used the New Brief Job Stress Questionnaire to examine stress reaction22). The participants rated 11 items using a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (almost never) to 4 (almost always). High scores indicate high levels of distress.

Frequency of valued actions. This indicator was assessed using the question: “How many of the three valued actions you set out have you carried out in total over the past week?”

Process outcomePsychological inflexibility. The study tested for PiF using the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II23,24). Seven items were rated using a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (never true) to 7 (always true). High scores indicate high levels of PiF.

OthersWhether or not to participate in each session. The study examined this factor using the following options: session 1, session 2, session 3, and non-participation in all sessions (select all that apply).

Job type. Job type was assessed using the following options: sales, clerical, planning clerical, professional workers, and others.

Statistical analysisThe data exhibited a hierarchical structure with observations nested within participants. The two-level hierarchical linear model is recommended for estimating the effects of interventions across cases25). In addition, applying the Bayesian estimation to single experimental design data is reasonable, because asymptotic assumptions are unlikely to be satisfied due to small sample sizes26). Therefore, the study evaluated the effect of the intervention using a hierarchical Bayesian model, in which Bayesian estimation was applied to a multilevel model. We used R (version 4.2.1; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) and applied the brms package27). The parameters and prior distribution are similar to those of Green et al.28), we assume that four chains with a length of 2,000 are generated, the burn-in period is 1,000, and the posterior distribution is approximated by 4,000 random numbers. The prior distribution assumes a non-informative prior. Furthermore, for well-being and PiF, we applied the SCED package29) to visualize each raw data and the SingleCaseES package30) to calculate the nonoverlap of all pairs (NAP)31) and Tau-U32). The study adopted the following tentative ranges as guidelines for the interpretation of the NAP: weak effects, 0–0.65; medium effects, 0.66–0.92; large or strong effects, 0.93–131). Similarly, we used the following tentative ranges as guidelines for the interpretation of the Tau-U in terms of the degree of changes: small, 0–0.20; moderate, 0.20–0.60; large, 0.60–0.80; large to very large, 0.80–133).

Well-being and psychological inflexibilityFollowing Green et al.28), we assumed that the model included a random effect as observations nested within participants and fixed effects as (1) an intercept, (2) a dummy indicator for the intervention phase, (3) a time within the baseline variable centered on the first three observations, and (4) a time within the intervention variable centered on the last three observations. To account for autocorrelation, the study applied a first-order autoregressive structure to the covariance matrix for within-individual residuals.

Work performance, work engagement, and stress reactionWe assumed that the model included a random effect as observations nested within participants and fixed effects as (1) an intercept and (2) a dummy indicator for the intervention phase. The other settings were the same as those for well-being and PiF.

Ethical approvalEthical approval for the study was received by the ethics committee of the institution to which the authors belong (No. 2021001). Employees who provided informed consent to participate in the study and to share their data with the OSF were included in the study. The design did not include the collection of information on adverse events. However, the ability to withdraw from participation in the study at any time was explained during the pre-study briefing and at the first session. In addition, the first author (AT), a clinical psychologist, was present at all sessions to address the occurrence of adverse events during the intervention.

Deviation from protocolWe report the following two deviations from the protocol. First, we opted to position the design of the study as a single-case A-B design instead of a pre-post trial. We originally planned to conduct repeated measurements and registered them as a pre-post trial because they could not be considered a single-case experimental design. However, when we referred to SCRIBE once again, we were able to organize the study design as a single-case A-B design. Therefore, we added the visualization of raw data and the calculation of effect sizes for well-being and PiF. Second, we initially planned to use text and response data written to a community space to explore the relationship between their data and the ACT-related indicators. However, analysis was impossible due to the unexpectedly low number of participant comments. Similarly, the study was unable to statistically examine the relationship between valued actions and PiF.

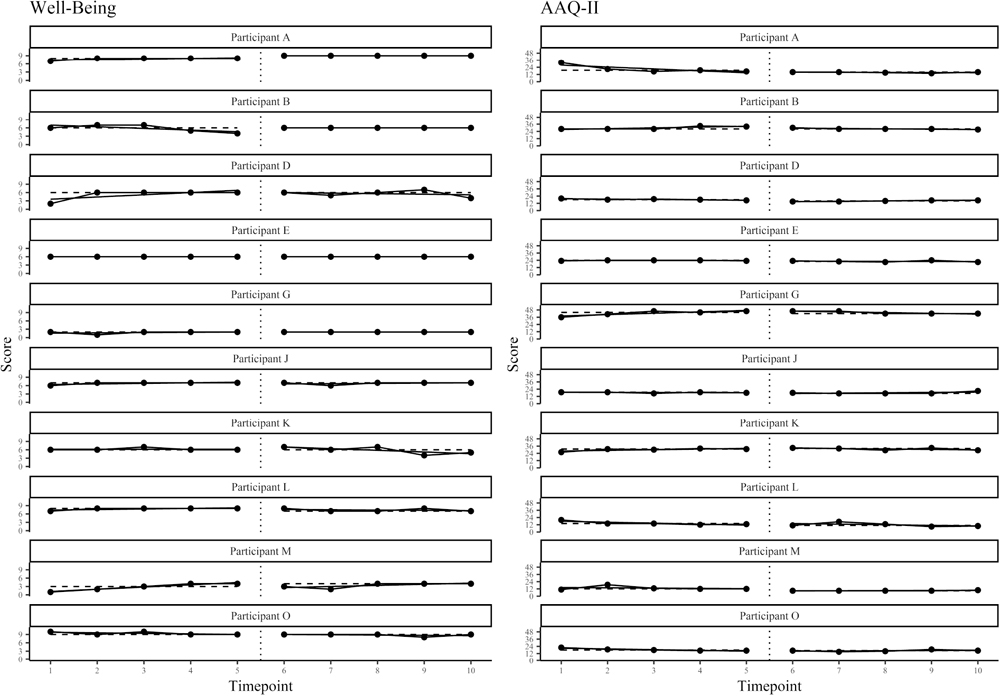

Fourteen participants met the inclusion criteria. Furthermore, referring to Green et al.28), they were required to have responded to at least four time points during the baseline (times 1–5) and intervention (times 6–10) phases, respectively. The sample for final analysis comprised 10 employees that identified as sales (n=3), clerical (n=4), planning clerical (n=1), and professional workers (n=2). As a result of the parameter estimation obtained using the multilevel model, Table 3 depicts the expected a posteriori estimates and 95% credible interval for each indicator. Figure 1 illustrates the raw data. Table 4 provides the NAP and Tau-U.

| Parameter | Well-being | AAQ-II | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random effects | ||||

| SD (Intercept) | 2.37 | [1.51, 3.75] | 7.23 | [4.08, 12.56] |

| Fixed effects | ||||

| Intercept | 5.84 | [4.42, 7.38] | 23.16 | [18.03, 27.98] |

| Intervention | 0.22 | [−0.31, 0.81] | −2.20 | [−5.60, 1.31] |

| time within baseline | 0.02 | [−0.32, 0.34] | −0.05 | [−1.26, 1.16] |

| time within intervention | −0.04 | [−0.35, 0.31] | −0.63 | [−1.81, 0.58] |

AAQ-II, Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II.

n=10, expected a posteriori estimation, [95% credible interval]. Cohen’s d for well-being and AAQ-II were 0.05 [−0.34, 0.45] and −0.19 [−0.58, 0.20], respectively, and the probability of the intervention effect being greater or less than 0 were 78.5% and 89.6%, respectively.

AAQ-II, Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II.

Vertical dotted lines indicate the point at which the intervention was implemented. Horizontal dashed lines indicate the median. Solid lines indicate the within-phase trends from ordinary least squares regression.

| Participant | Well-being | AAQ-II | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NAP | NAP 95% CI | Tau-U | NAP | NAP 95% CI | Tau-U | |||

| LL | UL | LL | UL | |||||

| A | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.84 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.72 |

| B | 0.50 | 0.21 | 0.79 | 0.20 | 0.70 | 0.35 | 0.91 | 0.60 |

| D | 0.52 | 0.22 | 0.81 | −0.12 | 0.96 | 0.59 | 1 | 0.64 |

| E | 0.50 | 0.21 | 0.79 | 0 | 0.82 | 0.45 | 0.96 | 0.64 |

| G | 0.60 | 0.27 | 0.85 | 0.12 | 0.44 | 0.17 | 0.76 | 0.16 |

| J | 0.50 | 0.21 | 0.79 | −0.16 | 0.68 | 0.33 | 0.90 | 0.24 |

| K | 0.44 | 0.17 | 0.76 | −0.12 | 0.34 | 0.11 | 0.68 | −0.12 |

| L | 0.30 | 0.09 | 0.65 | −0.56 | 0.78 | 0.41 | 0.94 | 0.28 |

| M | 0.64 | 0.30 | 0.88 | −0.08 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.96 |

| O | 0.24 | 0.07 | 0.61 | −0.36 | 0.78 | 0.41 | 0.94 | 0.20 |

AAQ-II, Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II; CI, confidence interval; LL, lower limit; NAP, nonoverlap of all pairs; UL, upper limit.

NAP and Tau-U were calculated to show improvement if the sign is positive.

Out of the 14 participants, only those who responded at least two time points from times 1, 7, and 10 were included in the analysis. The sample comprised 13 employees that identified as sales (n=3), clerical (n=5), planning clerical (n=2), professional workers (n=2), and others (n=1). As in Table 3, the results are shown in Table 5.

| Parameter | WHO-HPQ | UWES-3 | Stress reaction | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random effects | ||||||

| SD (Intercept) | 1.51 | [0.23, 3.02] | 1.03 | [0.60, 1.71] | 7.22 | [3.72, 11.86] |

| Fixed effects | ||||||

| Intercept | 6.26 | [5.23, 7.41] | 2.31 | [1.72, 2.92] | 19.97 | [15.87, 24.38] |

| Time (time1 vs. time10) | −0.32 | [−1.22, 0.57] | −0.08 | [−0.47, 0.34] | −0.49 | [−3.76, 2.66] |

Stress reaction, 11 stress reaction items on New Brief Job Stress Questionnaire; UWES-3, Three-item Utrecht Work Engagement Scale; WHO-HPQ, World Health Organization Health and Work Performance Questionnaire.

n=13, expected a posteriori estimation, [95% credible interval]. Cohen’s d for WHO-HPQ, UWES-3 and stress reaction were −0.17 [−0.97, 0.64], 0.05 [−0.76, 0.85], and 0.05 [−0.76, 0.85] respectively, and the probabilities of the intervention effect being greater or less than 0 were 22.2% (greater), 32.3% (greater), and 62.0% (less).

A visualization of changes in valued actions for the 11 participants at all four time points from times 7 to 10 is published in the OSF.

The study aimed to examine the effects of the online group program based on ACT for young employees. The hypothesis was not supported by any indicator: the primary outcome of well-being; the secondary outcomes of WP, WE, and stress reaction; and the process outcome of PiF. Moreover, regarding the Tau-U of the participants, more than half displayed moderate or larger positive changes in PiF, while more than half showed small changes in well-being, including many negative changes, with no consistency across participants. The results were not consistent with previous study that found that ACT reduced distress and stress and improved psychological flexibility and well-being6). WP and WE also did not support the hypothesis. The study inferred that four major reasons underlie this result. First, the hypothesis on well-being was unsupported; however, we noted that few studies were the subject of review and that the interpretation of the results was limited in the previous research6,10). Therefore, further accumulation of evidence on well-being is needed. Second, the reason for the lack of improvement in work-related indicators, such as WP and WE, was that we did not limit the domains of value to the work context of the program. As the intervention aimed to improve the well-being of employees, the participants were tasked to consider their overall value in life and not only at work. Third, regarding the stress reaction not supporting the hypothesis, ACT does not have an immediate effect on stress reduction6). Additionally, the study measured WP in a shorter period than did previous studies. Although the period from times 1 to 10 in the current study was approximately 1.5 months, previous studies evaluated WP after 3 months8) or 1 year7). In other words, measuring it using long-term data may be necessary to examine the impact of intervention on stress reaction and WP. Fourth, it did not improve PiF, despite the probability of the intervention effect being less than 0 being 89.6%. This result is consistent with that of a study that demonstrated that an online ACT intervention for youth exerted little effect on the improvement of PiF10). Morey et al.10) recommend the use of outcome variables that are appropriate for the target population of the study; thus, using the Work-related Acceptance and Action Questionnaire34,35), which is a measure of psychological flexibility that considers the work context, may have been preferable in this study. As an additional note, one of the reasons for the scarce comments on the community space is that the participants were invited to the same community space and may have felt reluctant to comment. Therefore, allocating the participants into several small groups may be necessary to encourage them to comment.

The study had four limitations. First, it did not employ randomization. Internal validity could be increased by classifying participants into multiple groups and randomly determining when to begin the intervention. Second, we did not obtain demographic characteristics of the participants. Disclosure of necessary demographic characteristics while protecting the privacy of participants would be helpful in interpreting the findings14). Third, only one item was used to measure well-being. The item was used for the following reasons: it has been used in a survey conducted by the Cabinet Office in Japan for use in policy management, and it is suitable for reducing burden on participants whose well-being is measured at a high frequency, because the number of items is minimal and easy to understand. Three conceptual approaches are generally used for subjective well-being: hedonic, evaluative, and eudaimonic conceptions36). However, the item focuses only on the evaluative perspective and fails to consider the others. Future research should specifically capture the eudaimonic aspects of well-being37). Fourth, in this study, outcome variables were not examined for measurement properties with reference to the COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments38), except for WP. Thus, we recommend that future studies use high-quality outcome variables that were developed based on this guideline.

In conclusion, the online group program based on ACT for young employees did not improve well-being. Future studies should improve the accuracy of the verification of effectiveness by reviewing the outcome variables and collecting long-term data.

The authors are grateful to Enago (www.enago.jp) for the English language editing.

MT and AT planned the study design and developed the intervention program. AT acquired, analyzed, and interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript, and MT revised it critically. AT and MT approved the final version.

The authors are an employee of the ADVANTAGE Risk Management Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan. The intervention content was created for in-house training in this study and was not a service currently provided as a product by the affiliated organization of the authors.

The data underlying this manuscript are available in the OSF (https://osf.io/y7n9r/).

The authors are engaged in research activities during their working hours at their workplace. They are not provided financial resources to create programs or materials.

The pre-registration is published in the OSF (https://osf.io/z8ghb).