2025 Volume 94 Issue 2 Pages 129-137

2025 Volume 94 Issue 2 Pages 129-137

In recent years, due to an aging workforce and labor shortages in the agricultural sector, coupled with difficulties in finding work in the welfare sector, agriculture-welfare collaboration has been promoted in Japan. However, owing to a lack of understanding in the agricultural sector about the abilities of individuals with disorders and how to deal with them, it has been assumed that individuals with disorders are unable to perform agricultural work. To address this lack of knowledge, in this study, 45 participants with intellectual disorders (Medical Rehabilitation Handbook A: 6 and B: 39) and 12 with mental disorders (Mental Disability Certificate Level 1: 1, Level 2: 8, and Level 3: 3) were asked to perform three tasks of varying difficulty levels in citrus orchards (bagging, harvesting, and fruit thinning). Their work abilities were evaluated based on measurements of work efficiency and observations of their work. The results showed that 96%, 50%, and 40% of the participants with disorders were able to comprehend the bagging (low difficulty), harvesting (medium difficulty), and fruit thinning (high difficulty) tasks, respectively. The average efficiencies of participants with disorders who comprehended the tasks were 55%, 71%, and 111% of those without disorders for bagging, harvesting, and fruit thinning, respectively. For fruit-thinning, six participants were more efficient than all participants without disorders. As described above, some aspects of the work efficiency of individuals with disorders at the start of the initiative were clarified. In the future, it will be necessary to clarify the negative effects of long work hours on physical strength and concentration, as well as on efficiency gains, through further experience and work process innovations.

In recent years, the agricultural industry has faced labor shortages due to depopulation and aging workforces in production areas. Consequently, there are an increasing number of elderly farmers without successors who have had to leave the farming profession. According to statistics from the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, the number of key agricultural workers in 2023 was approximately 20% lower than five years earlier. Population aging is a matter of concern in agriculture, as the average age of key agricultural workers is 68.7 years, and approximately 71% of them are aged 65 years and over. Notably, the number of new farmers has not increased in the last decade. Despite efforts to secure manpower during busy farming seasons, problems remain (Magaki, 2019).

Consequently, agriculture-welfare collaboration has attracted attention as a remedial countermeasure. Agriculture-welfare collaboration is defined as an approach aimed at promoting social participation with a sense of fulfillment and self-confidence among individuals with intellectual and mental disorders in the agricultural industry. This initiative can help alleviate the current shortage of workers and support the aging workforce in the industry. In recent years, efforts have been made to promote agriculture-welfare collaboration, including the establishment of an association by the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries and the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare in 2017. There are various approaches in agriculture-welfare collaboration, and the collaborative approach has been found to be effective in maintaining manpower during busy farming seasons (Yoshida, 2019). This pattern includes off-site work, where individuals with disorders carry out agricultural work at production sites, and on-site work, where they undertake shipment coordination and other work in warehouses etc. It has been observed that the agriculture-based approach includes hiring individuals with disorders by agricultural corporations, which is thought to improve agricultural management (Kikuchi 2021; Nakamoto and Sawano, 2020; Yoshida, 2019). In certain instances, cooperative initiatives have shifted to agriculture-based approaches based on direct employment (Yoshida, 2019).

Regarding the benefits of agriculture on welfare, outdoor work may have positive effects on human mental and physical skills, providing therapy, healing, and health support for people with disorders (Guirong and Oba, 2023). Some case studies have indicated that horticultural therapy can have beneficial effects on the vocational training of individuals with intellectual disorders (Joy et al., 2020), as well as on the mental well-being of individuals with mental illness (Siu et al., 2020). Questionnaire survey results from employment support staff have indicated their potential interest in horticultural therapy programs (Maebara et al., 2021).

The government’s promotion of agriculture-welfare collaboration has led to an increase in collaborative initiatives. However, little progress has been made in the direct employment of individuals with disorders by farmers and agricultural corporations, which is commonly referred to as an agriculture-based approach. According to a survey conducted by Yasunaka et al. (2009), one potential issue with agriculture-welfare collaboration is a lack of understanding of the abilities and methods for dealing with individuals with disorders. Therefore, prejudice that individuals with disorders cannot perform agricultural work that requires skilled techniques and knowledge remains. To address any potential misunderstanding, it would be beneficial to analyze data on the types of work that can be performed by individuals with disorders and their efficiency in doing these tasks. However, few reports include such data (Mattson et al., 1986; Nakazato et al., 2021). The availability of such data could not only challenge conventional thinking, but also facilitate planning for sourcing agricultural work for individuals with disorders. This study evaluated the work performance of individuals with intellectual and mental disorders in three cultivation tasks of varying difficulty: bagging, harvesting, and thinning of citrus fruits. The assessment was based on work efficiency measurements and observations made during the assigned tasks.

Mid-to-late-season citrus cultivars grown in a field at the Shizuoka Professional University of Agriculture were used. The field is flat but has ridges that are approximately 20 cm high. To ensure consistency, three varieties (‘Shiranui’, ‘Harumi’, and ‘Setoka’) with similar fruit size and shape were selected for this study. The height, amount of fruit set, and fruiting site were observed to vary from tree to tree, even for the same variety; therefore, the study was conducted at a height reachable without the use of a stepladder.

Experimental subjectsThe study involved 72 participants, of whom 57 had disorders and 15 did not (further details regarding this are shown in Table 1). A Medical Rehabilitation Handbook is issued to individuals diagnosed with intellectual or developmental disorders with an IQ of 80–89. A grading system of A for severe and B for medium or mild disorders is used for this certificate, in accordance with the Shizuoka Prefecture Rehabilitation Certificate Evaluation Guideline (https://www.pref.shizuoka.jp/_res/projects/default_project/_page_/001/023/697/hanteiyouryou.pdf). A Mental Disability Certificate is issued to individuals with mental disorders. Lower numbers on this certificate indicate more severe grade disorders. To recruit individuals with disorders, five employment support establishments were contacted and asked to send groups of four to six individuals with disorders, each accompanied by one or two welfare staff members. The comparison group, on the other hand, comprised individuals without disorders who had no prior work experience. Following a thorough review by the Ethical Review Committee for Research on Human Subjects at the Shizuoka Prefectural University of Agriculture, all participants were provided with detailed information regarding the purpose of the study and given the opportunity to provide informed consent. The informed consent forms were signed by all participants.

Participant characteristics and tasks performed.

Three tasks of varying difficulty levels (bagging, harvesting, and fruit thinning) were designed to evaluate the work efficiency of individuals with disorders in citrus fruit cultivation. The difficulty level of each task was assessed based on the method described by Toyoda et al. (2016), which measures the degree of dexterity and the maximum number of attention allocations. The difficulty levels assessed by this method were similar, with only slight variations among tasks; 2-2, 2-1, and 2-1 for the degree of dexterity and maximum number of attention allocation for bagging, harvesting, and fruit thinning, respectively. However, each task required different levels of judgment, as explained below. Therefore, the three tasks were thought to have varying levels of difficulty. Bagging is generally considered to be the easiest task of the three due to the fact that there is no need to select the fruit to be worked on. Furthermore, the fruit bags themselves, which are made of elastic material (Sante® for citrus; Toray Coms Ehime Co., Ltd., Ehime, Japan), do not require delicate handling. Harvesting was anticipated to be a manageable task but was designed to be moderately difficult among the three tasks. Rather than simply detaching the fruit from the branches, the participants were instructed to harvest the fruit along with the entire fruit stalk branch from the base, and subsequently remove the fruit from the stalk branch. This process is commonly utilized in mid- and late-season citrus production. The difficulty level of harvesting is higher than that of bagging, because this task involves the time-consuming process of locating the base of the stalk branch. In addition, fruit thinning is considered the most challenging task because it can be difficult to determine which fruits to retain and how many to pick. The number of fruits to be retained must be adjusted according to various factors. This is commonly regarded as a challenging task for novices. In this study, participants were instructed to pick fruits in five different conditions: small, scratched, strangely shaped, discolored, and cracked. The overall evaluation was conducted based on these three tasks, which were almost equal in terms of degree of dexterity and maximum number of attention allocations, but differed in the difficulty level of the decision criteria.

Work proceduresThe procedure for each task was explained to the participants using visual aids such as photographs, diagrams, or actual objects. Afterward, a model was presented in the field, and participants were given the opportunity to practice by following it. Once they had demonstrated their ability to perform the task, the actual work commenced.

For bagging, participants carried a basket containing 100 bags over their shoulders and were instructed to bag all the fruits. The work was performed by hand. It was suggested to participants who may have difficulty opening bags to try inserting one hand into the bag, grasping the fruit, and then using the other hand to lift the end of the bag.

During harvesting, participants were instructed to carefully remove the fruit bag, cut the fruit stalk branch at the base, and cut the fruit stalk branch at the base of the fruit. Participants were required to wear gloves on both hands and carry a harvest basket over their shoulders to collect the removed bags and fruit.

For fruit thinning, the participants were trained to select fruits that had any one or more of the five characteristics. They were instructed to maintain a leaf-to-fruit ratio of 100 (1 fruit per 100 leaves). If there were two or more fruits per 100 leaves that did not meet the conditions for fruit thinning, the participants were instructed to keep only one fruit that they deemed best and discard the others. They were informed of the approximate volume of space occupied by 100 leaves, allowing the task to be completed without having to count the leaves. They were advised to twist their wrists while pulling the fruit instead of pulling it in one direction for better efficiency. After picking, the fruit was placed in a harvest basket on their shoulders. The participants were required to wear gloves on both hands during this task.

SurveysSurveys were conducted between 2020 and 2023 at the appropriate time each task was carried out. The time allotted for each task was 30 min. However, to avoid affecting the measurement of work efficiency owing to replenishing bags or transferring harvested fruit to containers, work was terminated when 100 bags were filled during bagging or when the harvest basket was full during harvesting. Evaluations were conducted to assess the quantity and quality of work done during the tasks. Throughout the study, the participants were closely monitored to check their comprehension of the procedures involved in each task, whether the fruit was covered inside the bag during bagging, whether the fruit was cut at the base of the fruit stalk branch during harvesting, and whether the leaf-fruit ratio was correct during fruit thinning. Following the completion of the work, the number of bags used for bagging, the number of fruits harvested, and fruits thinned were counted. The effectiveness of double cutting in harvesting and the attributes of the fruits picked during thinning were also evaluated. After completing all the surveys, welfare staff knowledgeable about the characteristics of the individual participants were consulted for feedback on the results obtained. Interviews with staff were conducted face-to-face to explain the results of work comprehension and work efficiency for each participant. An evaluation was obtained to verify the validity of the results, that is, to check if these were predictable.

Statistical analysisStatistical analyses were conducted for individuals classified according to the Medical Rehabilitation Handbook B, which had the largest sample size as this study aimed to measure the work efficiency of individuals with disorders. For each task, a single regression analysis was performed to assess age-related differences, and a t-test with unequal variance was conducted to assess sex-related differences. A Pearson’s chi-square test was conducted on individuals classified according to the Medical Rehabilitation Handbook B and all those with disorders to ascertain the differences in the comprehension percentages of the three tasks. A Pearson’s chi-square test was also conducted for each pair of tasks on the same categories with Bonferroni’s correction (5% significance level; P < 0.0167).

In the bagging experiment, the vast majority of participants with disorders (45 of 47) were able to comprehend the task of centering the fruit in the bag (Table 2). It was unclear whether the remaining two participants comprehended the task because some fruits that were bagged were not centered in the bag. In contrast, all nine participants without disorders were able to comprehend the task. However, participants with and without disorders faced difficulty completely covering the fruit with the bag when other branches or spines obstructed their work.

Comprehension of the three tasks by individuals with different types and levels of disorders.

In the harvesting experiment, 50% of the 38 participants with disorders could comprehend the 2-step cut method used to harvest the stalk and fruit (Table 2). Among those with intellectual disorders classified as B according to the Medical Rehabilitation Handbook, 59% were able to comprehend it, while 17% of those classified as A in the Medical Rehabilitation Handbook were able to do so. With regard to individuals with mental disorders, it was found that 50% of those with Level 3 and 2 certificates were able to comprehend the instructions, while those with a Level 1 certificate expressed uncertainty about their comprehension. Of the 19 who were deemed to not comprehend or be unsure of how to carry out the task, none were unable to harvest at all; 13 were unable to find the base of the fruit stalk branch and five were unable to cut the branch twice correctly (two did not comprehend either task). However, all five participants without disorders were able to complete the task successfully, although a few fruits harvested by these participants still had fruit stalk branches.

In the fruit-thinning experiment, 17 of 42 (40%) participants with disorders were able to comprehend the leaf-fruit ratio (Table 2). Among those with mental disorders graded B based on the Medical Rehabilitation Handbook, 12 of 30 (40%) were able to comprehend, while all five Medical Rehabilitation Handbook A participants were unable to comprehend. For individuals with mental disorders, all three Level 3 certificate participants were able to comprehend the information, whereas only two out of four Level 2 certificate participants were able to comprehend the task. Among the participants who could not comprehend the task, eight focused on only one or two types of fruit, two observed too carefully before judging, three sought advice from staff, and three took more fruit than was appropriate based on the recommended leaf-fruit ratio. In contrast, all the participants without disorders demonstrated clear comprehension of the task.

The results of the Pearson’s chi-square test indicated statistically significant differences among the three tasks in the percentage of participants who comprehended the tasks in both cases for all individuals with disorders (χ2 = 43.00, df = 4, and P < 0.01) and for those classified as B based on the Medical Rehabilitation Handbook (χ2 = 30.64, df = 4, and P < 0.01). A significant difference was observed between the comprehension of tasks related to bagging and harvesting, and those related to bagging and fruit thinning, as determined by the Pearson’s chi-square test followed by Bonferroni’s correction (5% significance level; P < 0.0167). These differences were observed in both cases for all individuals with disorders and those participants classified as B based on the Medical Rehabilitation Handbook. No significant difference was observed between harvesting and fruit thinning.

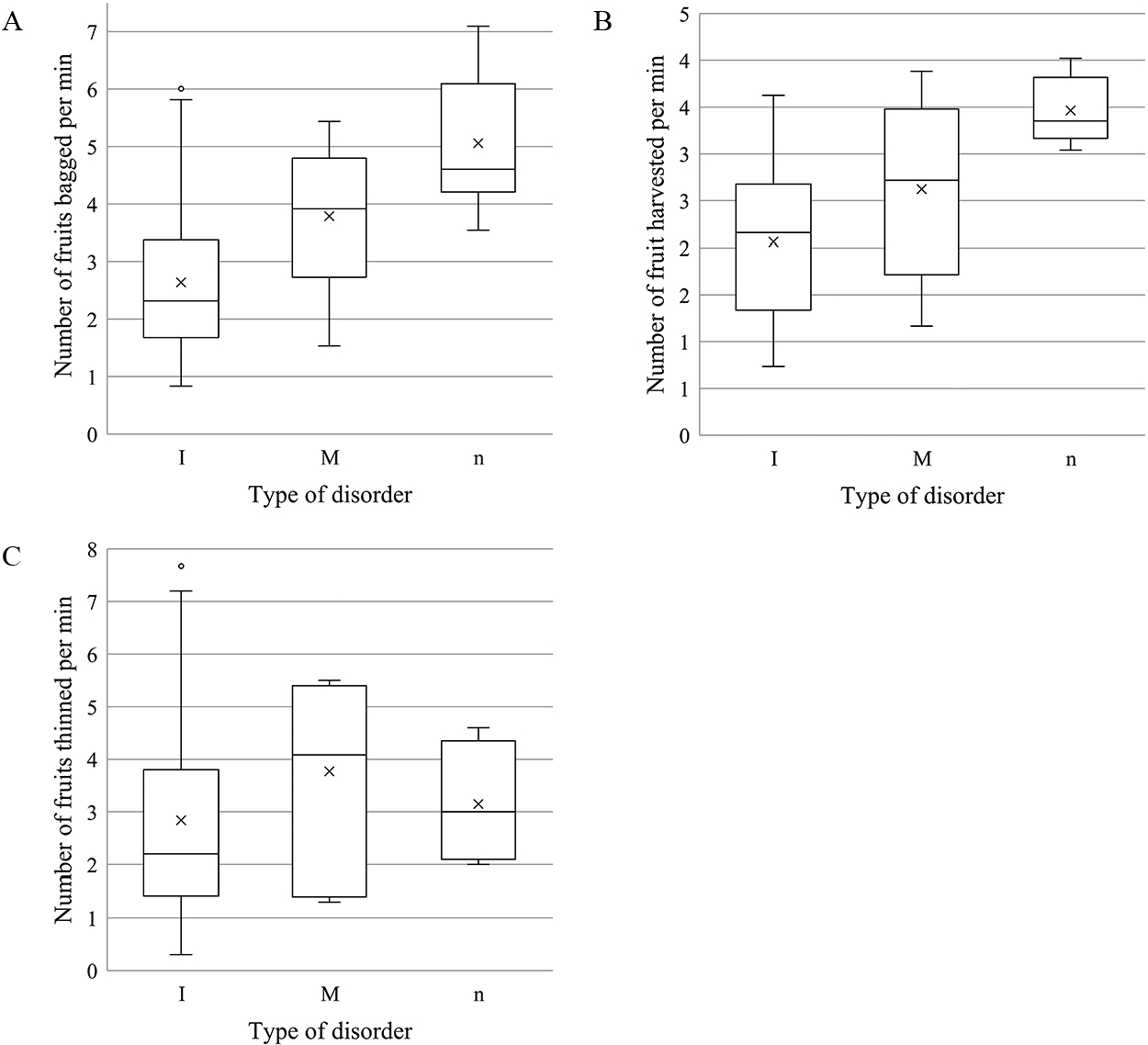

Speed of workFigure 1 displays the results of the work efficiency for each task. Among the 38 individuals with intellectual disorders, the average efficiency of bagging was 2.6 fruits per min, which is 52% of the average value of 5.1 for the nine individuals without disorders (Fig. 1A). Among the nine individuals with mental disorders, the efficiency was 3.8, which is 75% of the average value of individuals without disorders. Among the 34 individuals classified as B based on the Medical Rehabilitation Handbook, no significant correlations with age (R2 = 0.02, t = 0.72, and P = 0.47, based on single regression analysis, Fig. S5A) or sex (P = 0.45, based on a t-test with unequal variance, Fig. S6A) were observed. The fastest participant at bagging was a participant without disorders, who completed 7.1 fruits per min, while the slowest was a participant with disorders, who completed 0.8 fruits per min (Fig. 2A). Among the nine participants without disorders, the slowest participant completed 3.5 fruits per min. Of the 47 participants with disorders, 14 (30%) showed better efficiency than the slowest individual without disorders, and 13 were able to comprehend the task. Three of these 13 (6%) participants were faster than the average for participants without disorders. Seven of these 13 had intellectual disorders (Medical Rehabilitation Handbook B), and six had mental disorders (one with level 1, four with level 2, and one with level 3). Moreover, 32 of the participants with disorders were able to place the fruit in the center of the bag, albeit at a slower pace than the slowest individual without disorders.

Work efficiency by type of disorder for three tasks in citrus cultivation. A: Bagging, B: Harvesting, C: Fruit thinning. Type of disorders; ‘I’ refers to intellectual or developmental disorders, ‘M’ refers to mental disorders, and ‘n’ indicates without disorders. Data from participants who did not comprehend the task or were unsure are included in this graph. Due to the limited number of participants with mental disorders and those without disorders, statistical analysis was not possible.

Work efficiency of each individual for three tasks in citrus cultivation. A: Bagging, B: Harvesting, C: Fruit thinning. Asterisks indicate comprehension of the task. Black bars in the graph indicate individuals without disorders.

For harvesting, the average efficiency of the 33 individuals with intellectual disorders was 2.1 fruits per minute, which is 60% of the average value of 3.5 for the five individuals without disorders (Fig. 1B). That of five individuals with mental disorders was 2.6, which is 76% of the average value of individuals without disorders. There were no significant correlations with age (R2 = 0.02, t = 0.69, and P = 0.50, based on single regression analysis, Fig. S5B) or sex (P = 0.08, based on t-test with unequal variance, Fig. S6B) among the 27 individuals classified as B based on the Medical Rehabilitation Handbook. One of the participants without disorders had the fastest harvest rate of 4.0 fruits per min, whereas the slowest rate of 0.7 was seen in one of the participants with disorders (Fig. 2B). Among participants without disorders, the slowest harvest rate was 3.0. Of the 38 participants with disorders, six were able to perform the task faster than the slowest participant without disorders. Among these six participants, four (11%) were capable of comprehending the 2-step cut process required to remove fruit branches from the base. Two (5%) of these four participants had a harvest rate faster than the average of the participants without disorders. Three of these four participants had intellectual disorders (two with Medical Rehabilitation Handbook B and one with Medical Rehabilitation Handbook A), while another had a level 2 mental disorder. Furthermore, it was observed that 15 individuals with disorders were able to comprehend the 2-step cut process for the fruit stalk branch, albeit at a slower pace than the slowest individual without disorders.

For fruit thinning, the average efficiency of the 35 individuals with intellectual disorders was 2.8 fruits per minute, which is 90% of the average value of 3.2 for the four individuals without disorders (Fig. 1C). That of seven individuals with mental disorders was 3.8, which is higher than the average of the individuals without disorders (120%). No significant correlation was observed with age (R2 = 0.04, t = 1.11, and P = 0.27, based on single regression analysis, Fig. S5C) or sex (P = 0.07, based on t-test with unequal variance, Fig. S6C) among the 30 individuals classified as B based on the Medical Rehabilitation Handbook. Participants with disorders showed both the fastest and slowest picking rates of 7.7 and 0.3 fruits per min, respectively (Fig. 2C). Among four participants without disorders, the fastest picking rate was 4.6 and the slowest was 2.0. Of the 42 participants with disorders, 25 were faster than the slowest participants without disorders, and 14 (33%) could comprehend the leaf-fruit ratio. Eight (19%) of them were faster than the average of the participants without disorders, and six (14%) were faster than the fastest participants without disorders. Ten of these 14 participants with intellectual disorders were Medical Rehabilitation Handbook level B, while the remaining four had mental disorders (two with level 3 and two with level 2). Furthermore, it was noted that three other participants were able to comprehend the leaf-fruit ratio, albeit at a slower pace than the slowest participant without disorders.

Welfare staff opinions of the resultsAll staff members from the five welfare establishments commented that the results were largely predictable, although those for 17 of the 57 participants (30%) were lower than predicted (Table 3). The results for 39 participants (68%) were predictable. Some staff members noted a lower work efficiency than expected, likely because the participants were unaccustomed to working in an unfamiliar place. In addition, welfare staff mentioned that many participants improved their work efficiency once they became accustomed to it, suggesting the potential for improved performance in agricultural work with further experience. It has also been pointed out that work efficiency can be improved by devising work procedures and dividing roles. However, some individuals may find it challenging to maintain focus for extended periods.

Evaluation of the validity of work efficiency results by welfare staff.

This study aimed to evaluate the work abilities of people with disorders in agricultural work and their level of efficiency. First, it evaluated the types of work that could be performed by individuals with disorders. Three tasks with varying levels of difficulty were set, and the proportion of people who were able to comprehend the tasks differed according to the difficulty level. In the bagging task, for which the difficulty was low, 96% of the individuals with disorders were able to comprehend the task (Table 2). This percentage decreased to 50% in the harvesting task, for which the difficulty was medium, and to 40% for the fruit thinning task, for which the difficulty was high. The results confirm that work difficulty is inversely proportional to comprehension level. Bagging was considered to have a higher level of comprehension, because it was not necessary to determine which fruit to work on. In contrast, harvesting required cutting from the base of the fruit stalk branch, and it was difficult for some participants to find this, demonstrating their poorer comprehension of the task. With regard to the fruit thinning task, some participants struggled to comprehend the established ratio of one fruit per 100 leaves and to estimate the amount of 100 leaves. Additionally, many participants had difficulty recalling and handling all five characteristics that required the fruit to be discarded (small, scratched, strangely shaped, discolored, and cracked). Therefore, it was suggested that while simple tasks can be entrusted to individuals with disorders, only a limited number can handle more complex tasks.

These findings can be helpful to farmers considering the implementation of agricultural-welfare partnerships with limited information. However, it is important to note that this conclusion is based on certain assumptions made at the beginning of the initiative without any accumulation of experience or significant data. It has been demonstrated that individuals with disorders can develop skills as they gain experience (Nakamoto and Sawano, 2020). Additionally, tasks for individuals with disorders can be expanded by subdividing the tasks, devising work procedures, and improving work environments (Nakamoto, 2019; Satake and Hayashi, 2020, 2022). This was also pointed out by the welfare staff who accompanied the individuals with disorders. Furthermore, not all farmers follow harvesting procedures that require the removal of the entire fruit stalk branch. Notably, even the most productive citrus in Japan, Satsuma mandarin, is not harvested using this procedure. Therefore, it can be assumed that individuals with disorders may have a greater potential to participate in harvesting than the current results suggest. Regarding fruit thinning, individuals who selected only one or two of the five characteristics were judged not to have fully comprehended the task. However, such individuals can still be considered if they share the fruit thinning task when working in groups. Conversely, some of those who did not comprehend the task fully dropped more fruit than necessary during fruit thinning, whereas others left a few fruit stalk branches on the fruit during harvesting. Therefore, welfare staff and farmers will need to pay attention to prevent mistakes.

The efficiency of the participants in carrying out the tasks was also evaluated. Among the participants with disorders who comprehended the tasks, 28% were faster than the slowest participants without disorders at bagging, whereas the figures were 13% and 34% for the harvesting and fruit thinning tasks, respectively. Some participants with disorders were more efficient than those without disorders in certain situations. This demonstrates that some individuals with disorders can work as well as, or better than, those without disorders. Participants with disorders who comprehended the tasks had an average work efficiency of 55% for bagging, 71% for harvesting, and 111% for fruit thinning, compared to the average of participants without disorders. Some participants appeared to struggle and took longer to make decisions, while others moved slowly, it can be concluded that their work speed was often slower than that of participants without disorders. The reason the average efficiency in the fruit thinning task was the same for both groups was thought to be because the participants without disorders worked carefully during this task. Most participants without disorders who had no experience with fruit thinning stated that it was difficult to judge the fruit to be picked. It was previously reported that seven individuals with developmental disorders were, on average, 40% as efficient as the norm (experienced workers) at harvesting apples (Mattson et al., 1986). In comparison to the present study, several factors contributed to the reduction in efficiency, including the large number of participants with severe disabilities (four of the seven participants were IQ 25–49, and four had physical disabilities) and the use of ladders in the work. Therefore, the results of the present study suggest that there are situations in which work efficiency could be higher than the above results (Mattson et al., 1986), although they cannot be simply compared. The results were deemed reliable based on feedback from the welfare staff who assisted the individuals with disorders.

As described above, some aspects of the work efficiency of individuals with disorders at the start of the initiative were clarified. This information can provide insight for setting the workload and determining labor costs when hiring individuals with disorders. Although work efficiency may vary depending on the nature of the work and the participants, it is expected to be close to the average value because several individuals are often dispatched from welfare establishments. In practice, welfare establishments dispatch workers who are expected to achieve certain results based on each individual’s occupational skills. Therefore, achievement of the high work efficiency observed in the present study may be possible.

This study clarified the work efficiency of individuals with disorders at the beginning of their efforts in agricultural work of different difficulty levels. The results are useful for producers considering the introduction of agriculture-welfare collaborations. The results can be used to make decisions on whether or not to collaborate with welfare establishments, how to collaborate, and how to prepare a work plan. On the other hand, it should be noted that this study was conducted under relatively good working conditions; some workers with disorders may be limited in their ability to work on inclines or use stepladders due to the specific nature of their disorders or while under the influence of medication. It should also be noted that this study is not a comparison with experienced workers, as it was conducted on participants with no prior work experience, regardless of disorder. The work efficiency ratios obtained in this study for individuals without disorders do not apply to farmers who previously employed experienced seasonal workers if they change their contractors to welfare establishments. In addition, welfare staff and farmers need to be aware that farming is a dangerous and accident-prone occupation (Molineri et al., 2015; Shortall et al., 2019) and they may need to take more safety precautions than they would when employing workers without disorders. Future research should investigate the effects of physical fatigue and reduced concentration when working for extended periods, as well as on efficiency gains through experience and work process innovations, as suggested by the welfare staff of the establishments that participated in the present study. Improving work efficiency can lead to the expansion of agriculture-welfare collaboration initiatives and help solve the issue of labor shortages in the agricultural industry. In addition, the agricultural industry can contribute to the realization of a symbiotic society by promoting the social participation of individuals with disorders.

We would like to thank everyone from the five employment support agencies: Tanpopo, Potlatch, Ibuki, Minori, and Works Tubasa, who participated in the farm work. This study was approved by the Ethical Review Committee for Research on Human Subjects of the Shizuoka Prefectural University of Agriculture (Approval Numbers: 20H001, 21H001, 22H002, and 23H001).