2025 Volume 94 Issue 4 Pages 429-437

2025 Volume 94 Issue 4 Pages 429-437

Dahlia (Dahlia variabilis) is a popular ornamental plant belonging to the Asteraceae family grown in many countries because of its wide variation in flower shape, size and color. Among its diverse attractive traits, flower color is one of the most important ornamental traits in dahlia. The pigments in dahlia flowers are flavonoids (anthocyanins, flavones, and 6′-deoxychalcones), and the presence and amount of these pigments determines the color of the flower. In this review, the history of research on dahlia flower color, biosynthesis of floral pigments focusing on anthocyanin biosynthesis, 6′-deoxychalcone biosynthesis and bicolor pattern formation, as well as unstable pigmentation in bicolor cultivars, are summarized. Finally, for future dahlia breeding, candidate genes determining flower colors are proposed.

Dahlia (Dahlia variabilis) is a popular ornamental plant belonging to the Asteraceae family grown in many countries because of its wide variation in flower shape, size and color. This wide variation is derived from a complex genetic background, that is, dahlia is considered to be an autoallooctaploid with a chromosome number 2n = 8x = 64 (Gatt et al., 1998; Lawrence, 1929, 1931a; Lawrence and Scott-Moncrieff, 1935) and a large genome (2C value = 8.27–9.62 pg; Temsch et al., 2008). More than 50,000 cultivars have been bred during the last century (McClaren, 2009). Since dahlias are easy to propagate vegetatively from tuberous roots and cuttings, it is easy to create new cultivars with a single cross. In Japan, cuttings are widely used for winter cut flower production (Konishi and Inaba, 1964; Naka et al., 2007). Some cultivars for garden plants are also propagated by seeds.

Among its diverse traits, flower color is one of the most important ornamental traits in dahlia. The pigments in dahlia flowers are flavonoids (anthocyanins, flavones, and 6′-deoxychalcones) (Table 1), and the presence and amount of these pigments determines the color of the flower. In this review, the history of research on dahlia flower color, biosynthesis of floral pigments focusing on anthocyanin biosynthesis, 6′-deoxychalcone biosynthesis and bicolor pattern formation are summarized.

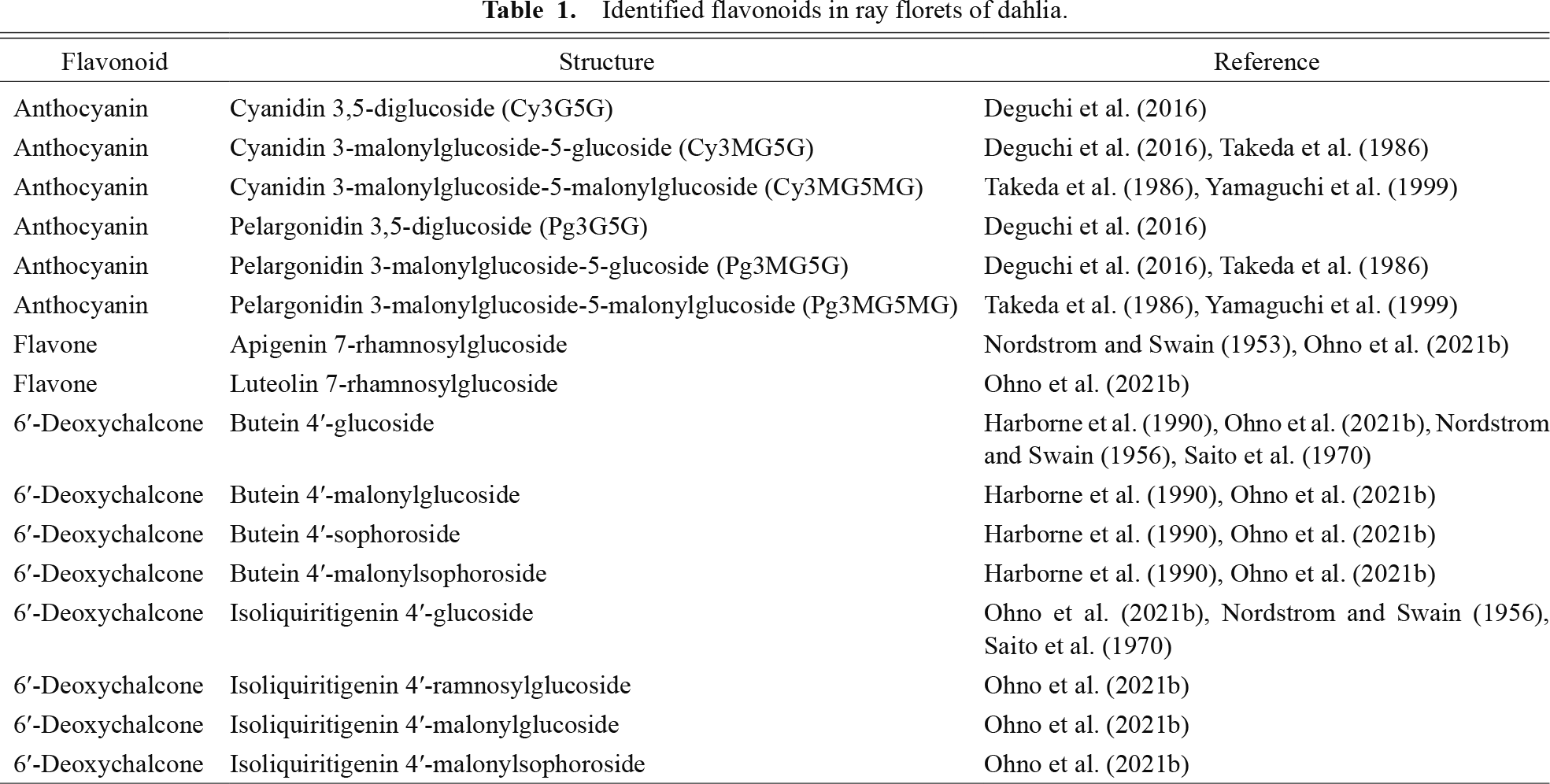

Identified flavonoids in ray florets of dahlia.

Dahlias have a wide variety of flower colors, and the National Dahlia Society classifies dahlia flowers into 17 colors (white, yellow, orange, bronze, flame, red, dark red, pink, lilac, lavender, mauve, purple, wines, violets, blends, bicolored, and variegated) (https://www.dahlia-nds.co.uk/about-dahlias/classification/). These flower colors have been the subject of many studies over the years (Bate-Smith et al., 1955; Broertjes and Ballego, 1967; Deguchi et al., 2016; Forkmann and Stotz, 1984; Harborne et al., 1990; Hazama, 1953; Lawrence, 1929, 1931a, b; Lawrence and Scott-Moncrieff, 1935; Nordström and Swain, 1953, 1956, 1958; Ohno et al., 2016, 2021b; Price, 1939; Saito et al., 1970; Singh et al., 1970; Tammes and Groeneveld-Huisman, 1939). Lawrence and his colleagues published a series of scientific papers on the genetics and cytology of dahlias (Lawrence, 1929, 1931a, b, c; Lawrence and Scott-Moncrieff, 1935). Based on numerous crossing experiments, they proposed that four genetic factors control dahlia flower color: A (light anthocyanin), B (heavy anthocyanin), I (ivory flavone), and Y (yellow flavone) (Lawrence and Scott-Moncrieff, 1935). They also predicted another factor, H, a yellow inhibitor (Lawrence and Scott-Moncrieff, 1935). As time progressed, the identification of floral pigments also progressed. Price (1939) reported a yellow flavonoid, butein (2′,3,4,4′-tetrahydroxychalcone), in dahlia ray florets. This discovery was the first report on the presence of butein in nature. Nordström and Swain (1953, 1956) reported the structures of flavones (apigenin and luteolin) and chalcones. Subsequently, the detailed structure of chalcones were identified as 4′-glucoside derivatives (Harborne et al., 1990; Ohno et al., 2021b). Also, the detailed structure of anthocyanins contained in flowers were identified as pelargonidin 3,5-diglucoside (Pg3G5G), pelargonidin 3-malonylglucoside-5-glucoside (Pg3MG5G), pelargonidin 3-malonylglucoside-5-malonylglucoside (Pg3MG5MG), cyanidin 3,5-diglucoside (Cy3G5G), cyanidin 3-malonylglucoside-5-glucoside (Cy3MG5G), and cyanidin 3-malonylglucoside-5-malonylglucoside (Cy3MG5MG) (Table 1; Deguchi et al., 2016; Takeda et al., 1986; Yamaguchi et al., 1999). As for flavones, apigenin 7-rhamnosylglucoside and luteolin 7-rhamnosylglucoside were identified in ray florets (Table 1; Nordström and Swain, 1953; Ohno et al., 2021b).

Subsequent research focused on genes and proteins. Fischer et al. (1988) reported the purification and characterization of dihydroflavonol 4-reductase (DFR) from flowers. Stich et al. (1994) reported 6′-deoxychalcone 4′-glucosyltransferase activity from ray florets. Wimmer et al. (1998) reported the presence of chalcone 3-hydroxylase (CH3H) activity in ray florets. Yamaguchi et al. (1999) reported anthocyanidin 3-glucoside malonyltransferase activity in ray florets, and the gene for anthocyanidin 3-O-glucoside-6″-O-malonyltransferase (3MaT) was subsequently identified (Suzuki et al., 2002). Ogata et al. (2001) reported isolation of anthocyanin 5-O-glucosyltransferase from flowers. From the 2010s to the 2020s, most flavonoid biosynthetic genes were isolated and analyzed (Deguchi et al., 2013, 2015; Hausjell et al., 2022; Maruyama et al., 2024; Ohno et al., 2011a, b, 2013, 2018b, 2022; Schlangen et al., 2010a; Thill et al., 2012). Furthermore, a transgenic blue flower dahlia expressing Commelina communis flavonoid 3′5′-hydroxylase (F3′5′H) was produced in 2012 (press released by Chiba University: https://www.chiba-u.ac.jp/about/files/pdf/20120605_dalia.pdf).

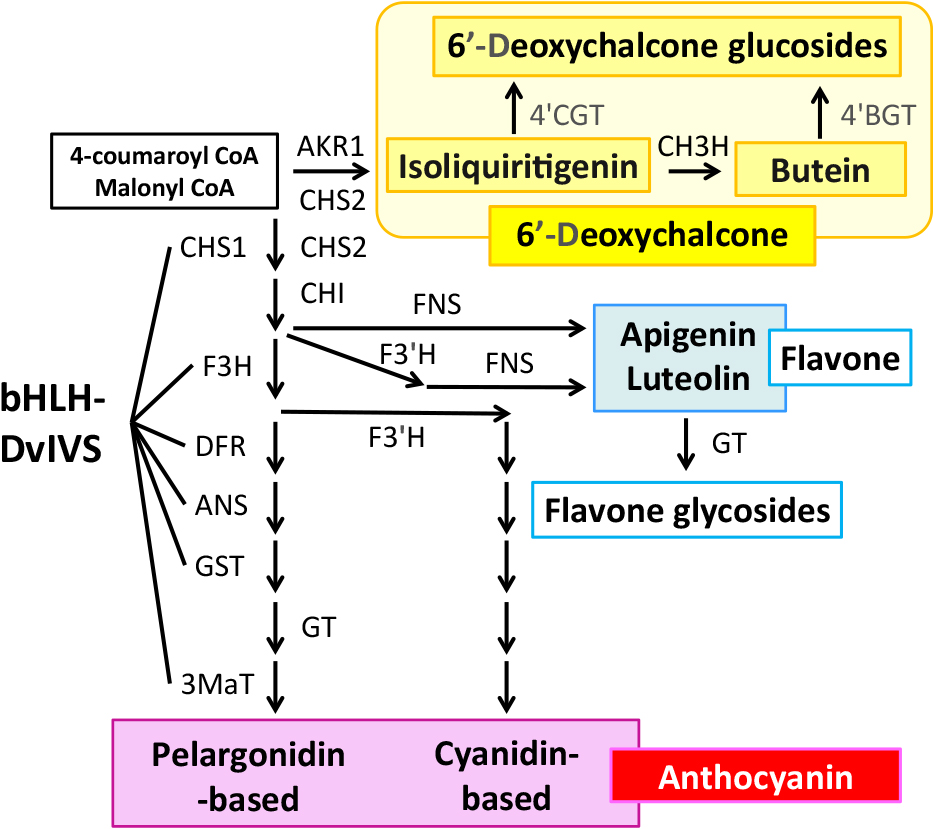

The anthocyanin biosynthesis pathway is one of the most well studied secondary metabolic pathways in plants (Please see reviews: Grotewold, 2006; Tanaka et al., 2008). Enzymes that catalyze the pathway are common in many plant species. The substrates of anthocyanin are 4-coumaroyl CoA and 3-malonyl CoA. In the first step, three molecules of 3-malonyl-CoA and one molecule of 4-coumaroyl-CoA are condensed by chalcone synthase (CHS) to form naringeninchalcone (2′,4,4′,6′-tetrahydroxychalcone). Then, chalcone isomerase (CHI), flavanone 3-hydroxylase (F3H), DFR, and anthocyanidin synthase (ANS) work to form anthocyanidin. Recently, glutathione S-transferase (GST) was demonstrated to be involved in the anthocyanidin biosynthesis step by dehydration of the ANS product (Eichenberger et al., 2023). Three major anthocyanidins are known, cyanidin, pelargonidin and delphinidin. Cyanidin is synthesized when flavonoid 3′-hydroxylase (F3′H) works in the pathway, delphinidin is synthesized when F3′5′H works in the pathway, whereas pelargonidin is synthesized when both F3′H and F3′5′H do not work. Dahlia accumulates cyanidin-based anthocyanins (Cy3G5G and Cy3MG5G) and pelargonidin-based anthocyanins (Pg3G5G and Pg3MG5G), and for biosynthesis of Pg3G5G and Cy3G5G, anthocyanidins are modified by anthocyanin 3-O-glucosyltransferase (3GT) and anthocyanin 5-O-glucosyltransferase (5GT), while for biosynthesis of Pg3MG5G and Cy3MG5G, 3MaT works in addition to glucosyltransferases.

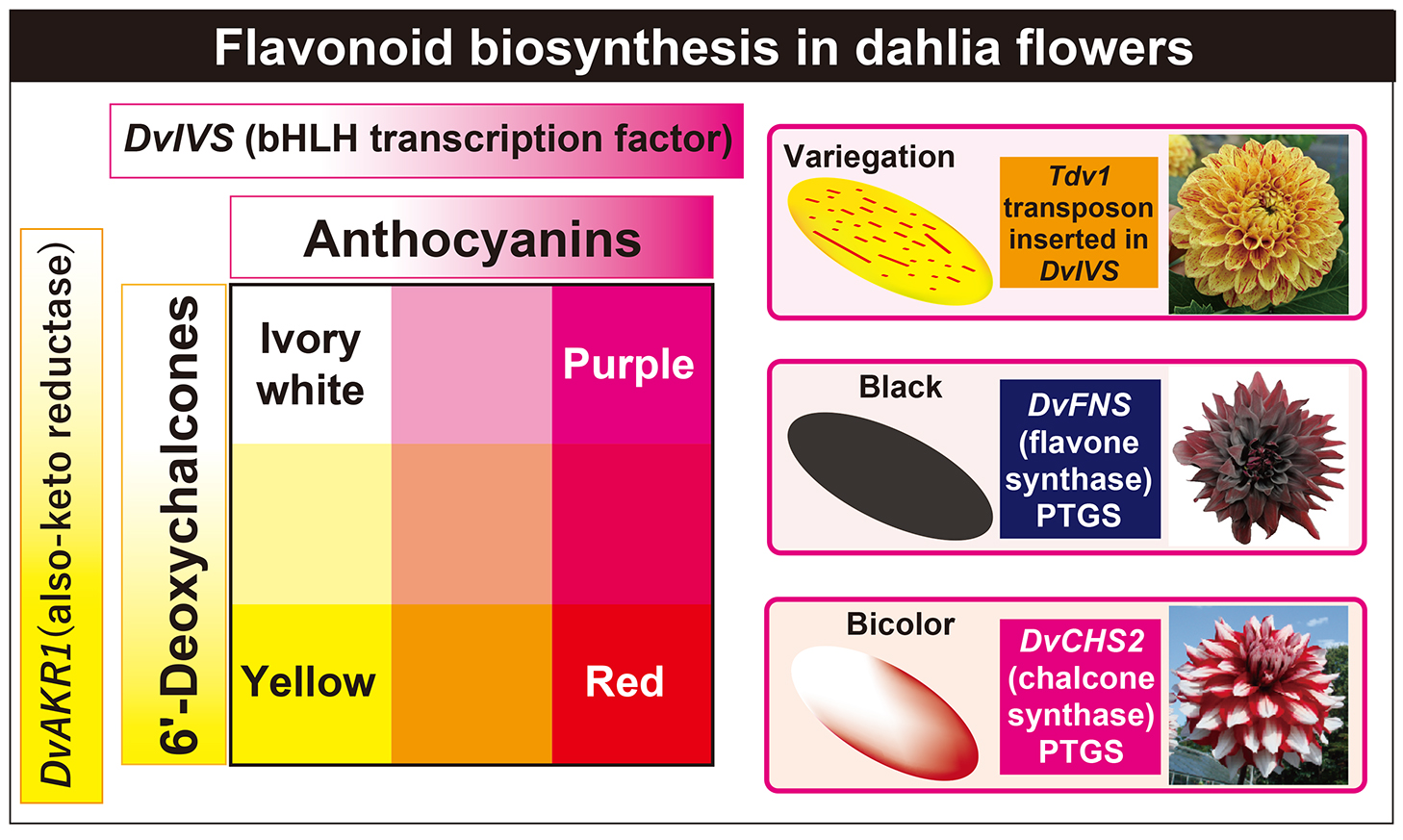

Generally, some of these anthocyanin biosynthetic enzyme genes are controlled by a transcription complex consisting of MYB, basic-helix-loop-helix (bHLH) and WD-repeat (WDR) transcription factors (Hichri et al., 2011; Koes et al., 2005; Lloyd et al., 2017; Xu et al., 2015). In dahlia, it was demonstrated that a bHLH transcription factor, DvIVS, which is an orthologue of petunia (Petunia hybrida) ANTOCYANIN 1 (Spelt et al., 2000) and morning glory (Ipomoea purpurea) IVORY SEED (IVS) (Park et al., 2007), is involved in anthocyanin biosynthesis (Ohno et al., 2011a). DvIVS controls expressions of DvCHS1, DvF3H, DvDFR, DvANS, DvGST, and Dv3MaT (Fig. 1; Ohno et al., 2011a, 2013; unpublished data). The expression level of DvIVS was correlated with the anthocyanin level in cyanic cultivars, and the genotype of the DvIVS promoter region and the expression level were correlated, indicating DvIVS is also involved in determining the intensity of flower color (Ohno et al., 2013).

The putative flavonoid biosynthetic pathway in dahlia. Abbreviations: AKR, aldo-keto reductase; ANS, anthocyanidin synthase; bHLH, basic helix-loop-helix; CH3H, chalcone 3-hydroxylase; CHI, chalcone isomerase; CHS, chalcone synthase; DFR, dihydroflavonol 4-reductase; F3H, flavanone 3-hydroxylase; F3′H, flavonoid 3′-hydroxylase; FNS, flavone synthase; GST, glutathione S-transferase; GT, glycosyltransferase; 3MaT, anthocyanidin 3-O-glucoside-6″-O-malonyltransferase; 4′BGT, butein 4′-O-glucosyltransferase; 4′CGT, chalcone 4′-O-glucosyltransferase.

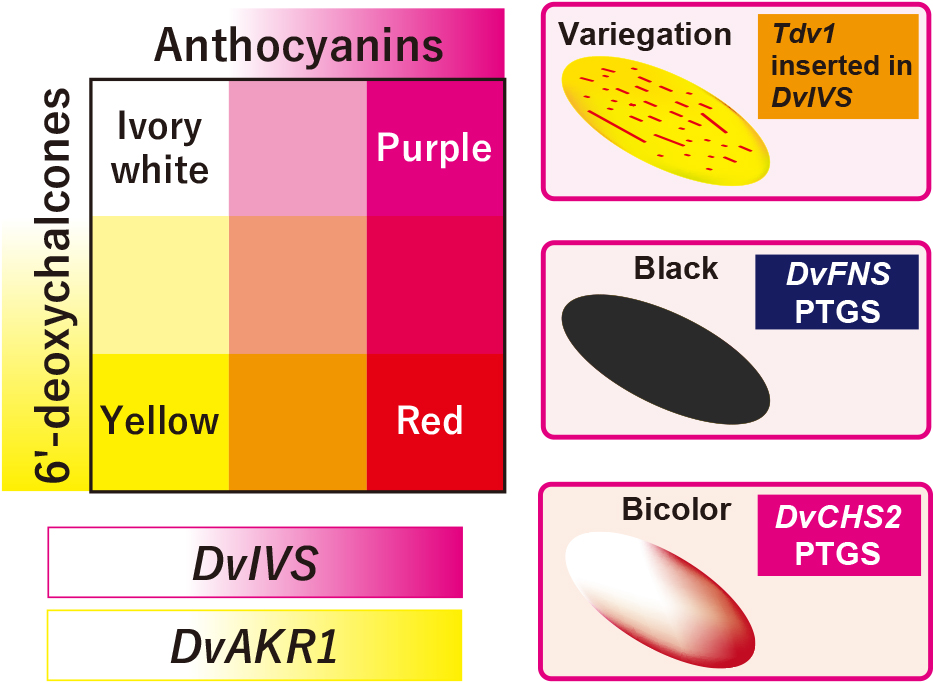

A variegated cultivar ‘Michael J’ has yellow ray florets with red variegations. Generally, a variegation phenotype results from insertion/deletion of transposable elements in a pigment biosynthesis gene (Iida et al., 2004). In ‘Michael J’, a 5.4-kb CACTA-family transposable element named transposable element of Dahlia variabilis 1 (Tdv1) was found in the fourth intron of the DvIVS gene in yellow ray florets, but not in red ray florets (Ohno et al., 2011a). Therefore, DvIVS and the inserted transposon were thought to contribute to the variegated phenotype.

One of the characteristic flower colors of dahlia is blackish, and this color is important in floriculture because a similar color with such a gorgeous appearance is not found in other species. Generally, black coloration is due to the accumulation of blackish pigments, high pigment content or accumulation of both anthocyanin and carotenoids. In dahlias, black flower color is due to the first two factors, accumulation of blackish pigments and high pigment content, especially high accumulation of cyanidin-based anthocyanins. Dahlia mainly accumulates four anthocyanins, Pg3G5G, Pg3MG5G, Cy3G5G, and Cy3MG5G, and among the four major anthocyanins, only Pg3MG5G had a bright color, whereas the other three anthocyanins had a dark color when they were resolved in a phosphate–citrate buffer solution (Deguchi et al., 2016). Usually, dahlia accumulates more 3MG5G-type anthocyanins than 3G5G-type anthocyanins; therefore, cultivars with a high Cy/Pg ratio and an abundant amount of anthocyanins can have a black appearance. In most black cultivars, these conditions were satisfied with post-transcriptional gene silencing (PTGS) of the flavone synthase (FNS) gene because DvFNS suppression removes substrate competition between anthocyanins and flavones, and all substrates are thought to be used only for anthocyanins (Deguchi et al., 2013, 2015). DvFNS expression is also involved in color fading of red ray florets in ‘Nessho’ and ‘Color Magic’, which exhibit color fading from autumn to spring in response to low temperatures (Kase et al., 2024; Muthamia et al., 2024; Okada et al., 2020; Suzuki et al., 2010).

Yellow pigments that confer yellow flower color are flavonoids, carotenoids and betaxanthins. Flavonoid compounds known to impart yellow flower coloration include aurone, chalcononaringein and 6′-deoxychalcone. In many Asteraceae plants, the yellow flower color is conferred by carotenoids, but in dahlia (Price, 1939) and species closely related to dahlias, such as Cosmos sulphureus (Geissman, 1942) and Coreopsis species (C. douglasii, C. gigantea and C. grandiflora) (Geissman, 1941a, b; Geissman and Heaton, 1943), the yellow flower color is conferred by flavonoids. Major flavonoids contributing to the yellow color in dahlia are 6′-deoxychalcones, isoliquiritigenin (2′,4,4′-trihydroxychalcone) and butein (2′,3,4,4′-tetrahydroxychalcone) derivatives. In the first step, isoliquiritigenin is synthesized from common flavonoid precursors 3-malonyl-CoA and 4-coumaroyl-CoA by CHS and aldo-keto reductase (AKR) (Fig. 1; Ohno et al., 2022). Isoliquiritigenin is converted to butein by CH3H (Schlangen et al., 2010b) or an allelic variant of F3′H in dahlia (Schlangen et al., 2010a). In coreopsis, butein is further oxidized by polyphenol oxidase (PPO) to produce 4-deoxyaurone (Kaintz et al., 2014; Molitor et al., 2015, 2016). Aurones in coreopsis and closely related species are 4-deoxyaurones, while aurones in snapdragon (Antirrhinum majus) are 4-hydroxyaurones (Nakayama, 2022).

Isoliquiritigenin is not only the precursor of butein, but also the precursor of isoflavone, and in addition to CHS, AKR is required for this reaction. AKRs are an enzyme superfamily of NAD(P)(H)-dependent oxidoreductases with broad physiological roles (Jez et al., 1997). In legume species such as soybean (Glycine max), AKRs named chalcone reductases (CHR) (although they are named chalcone reductase, it is most likely that its substantial substrate is not chalcone, but a polyketide intermediate produced during chalcone synthase catalysis: Bomati et al., 2005) were isolated and shown to be involved in isoliquiritigenin biosynthesis in the isoflavone biosynthesis pathway (Mameda et al., 2018; Welle et al., 1991). Since these CHRs belong to the AKR 4A subfamily, the AKR 4A gene expressed in dahlia ray florets was first explored to identify the AKR for isoliquiritigenin biosynthesis. However, the AKR 4A gene was not detected in ray florets, and only the AKR 4B genes were detected (Ohno et al., 2022; Walliser et al., 2021). This indicates that genes involved in 6′-deoxychalcone biosynthesis are different from isoflavone biosynthesis in legume species. Comparing a red-white bicolor cultivar ‘Shukuhai’ and its lateral mutant purple-white bicolor cultivar ‘Rinka’, DvAKR1 was isolated as isoliquiritigenin biosynthetic AKR gene. DvAKR1 gene expression and genotype correlated with 6′-deoxychalcone accumulation, indicating DvAKR1 is a determinant gene for 6′-deoxychalcone biosynthesis (Ohno et al., 2022). DvAKR1 belongs to the AKR 13 subfamily that includes Arabidopsis AT1G60710, Zea mays AKR2, Rauvolfia serpentine perakine reductase and Perilla setoyensis PsAKR. DvAKR1 was phylogenetically distant from the AKR 4A genes and DvAKR1 shares only 19% identity with GmCHR1, indicating isoliquiritigenin biosynthesis in dahlia and legume species have independent evolutionary origins (Ohno et al., 2022). DvAKR1 orthologous genes were isolated from phylogenetically close species that accumulate yellow flavonoids, such as bidens (Bidens aurea), Cosmos sulphureus and coreopsis, and these genes are responsible for the biosynthesis of isoliquiritigenin (unpublished data). Therefore, DvAKR1 and its orthologous genes may provide good clues to clarify the evolution of the yellow color in Asteraceae flowers.

Structures of 10 6′-deoxychalcones in dahlia ray florets were determined by HR-FABMS and NMR analysis, and three of them (butein 4′-malonylglucoside, butein 4′-sophoroside, and isoliquiritigenin 4′-malonylglucoside) are major yellow pigments in ray florets (Table 1; Ohno et al., 2021b). All three major pigments exhibit 4′-glucosylation. Glycosylation is one of the major modifications in flavonoids, enhancing solubility and facilitating transport into the vacuole (Bowles et al., 2005; Jones and Vogt, 2001). For glycosylation of 6′-deoxychalcone in dahlia, two 6′-deoxychalcone 4′-glucosyltransferase genes, chalcone 4′-O-glucosyltransferase (Dv4′CGT) and butein 4′-glucosyltransferase (Dv4′BGT), were identified (Fig. 1; Maruyama et al., 2024). Interestingly, these two glucosyltransferases have different substrate preferences: Dv4′CGT prefers glucosylation of isoliquiritigenin while Dv4′BGT prefers glucosylation of butein. Regarding chalcone 4′-O-glucosyltransferase, Am4′CGT, which is involved in aurone biosynthesis in snapdragon, has been reported (Ono et al., 2006). Am4′CGT is able to accept 2′,4,4′,6′-tetrahydroxychalcone and 2′,3,4,4′,6′-pentahydroxychalcone as substrates (Ono et al., 2006), and functional analysis indicated the substrate preference of Am4′CGT is similar to Dv4′CGT, but not exactly the same (Maruyama et al., 2024). Although other glucosyltransferases related to 6′-deoxychalcone have not yet been isolated in other species, the diversification of glucosyltransferase is also of interest.

Because almost all species are able to synthesize flavonoids, especially those that do not accumulate yellow carotenoids in flowers, 6′-deoxychalcone may be a good candidate pigment for molecular breeding of bright yellow flowers. Currently, CaMYBA, an anthocyanin MYB transcription factor in pepper (Capsicum annuum) is used for artificial accumulation of 6′-deoxychalcones by agro-infiltration (Ohno et al., 2022). This is because 6′-deoxychalcone was not detected when DvAKR1 and Am4′CGT were ectopically expressed, while 6′-deoxychalcone was detected when CaMYBA was co-expressed with them. The problem with this method is that not only 6′-deoxychalcone, but also anthocyanin accumulation, is induced. Since anthocyanin is not required for molecular breeding of yellow flowers, we are currently searching for a gene that only induces the accumulation of 6′-deoxychalcone and are studying the mechanism by which only 6′-deoxychalcone can be artificially accumulated. Further analysis will open the door to molecular breeding by 6′-deoxychalcones.

Another characteristic flower color in dahlia is bicolor which has a pigmented part and a white part in one ray floret. While flavonoid pigments (anthocyanins, flavones, and/or 6′-deoxychalcones) were detected from the pigmented part, no flavonoids were detected from the white part. This is an obvious difference of white flower cultivars in dahlia where flavones were detected (Ohno et al., 2011b). Loss of flavonoid in the white part is due to the downregulation of CHS. In red-white bicolor ‘Yuino’, DvCHS1 and DvCHS2 are expressed in the red part, while they are down-regulated in the white part (Ohno et al., 2011b, 2018b). This down-regulation is due to the PTGS of these two different CHS genes, even though they share 69% of nucleic acid sequences. PTGS of CHS has been reported in petunia (Koseki et al., 2005), soybean (Tuteja et al., 2004) and Japanese gentian (Ohta et al., 2022), and simultaneous PTGS of two or more CHS genes have also been found in petunia and soybean. PhCHSA and PhCHSJ are simultaneously silenced in petunia (De Paoli et al., 2009; Morita et al., 2012) and 9 CHS genes (GmCHS1-9) are silenced in the seedcoat of soybean (Tuteja et al., 2009). In dahlia, yellow-white bicolor cultivars that do not express DvCHS1 in ray florets still cause CHS PTGS, indicating DvCHS2 is more important for the occurrence of CHS PTGS. In petunia, tandemly arranged PhCHSA genes are required for PTGS induction (Morita et al., 2012), and in soybean, the I cluster of inverted GmCHS genes (GmCHS1, GmCHS3, and GmCHS4) (Todd and Vodkin, 1996) or a perfect inverted repeat of 1.1-kb truncated GmCHS3 sequences, GmIRCHS (Kasai et al., 2007), is required. In dahlia, the DvCHS2 gene copy number is twice as high in bicolor cultivars than in single color cultivars, indicating duplication of DvCHS2 may be involved in PTGS induction (Ohno et al., 2018b).

An interesting phenomenon observed in most bicolor cultivars is the color lability (instability) of ray florets; they frequently produce single-pigmented ray florets without the white part (Ohno et al., 2016; Tammes and Groeneveld-Huisman, 1939). In some cases, all ray florets in one inflorescence are pigmented, or some ray florets are pigmented and other ray florets are bicolored in one inflorescence. This unstable pigmentation in flowers or bracts is also found in petunia (Jorgensen, 1995) and bougainvillea (Ohno et al., 2021a). In the ‘Yuino’, a correlation between inflorescence color and flavonoid accumulation in leaves was observed (Ohno et al., 2016). ‘Yuino’ leaves accumulate flavonoids such as 6′-deoxychalcones and flavones (Ohno et al., 2018a). When an inflorescence had at least one red ray floret, the uppermost leaf accumulated these flavonoids, whereas when an uppermost leaf did not accumulate these flavonoids, the inflorescences were all bicolor ray florets. This tendency was also observed at the whole plant level, suggesting color lability of ray florets is not only related to changes in the color of ray florets, but also to changes in the state of the shoot apical meristem (SAM) (Ohno et al., 2016). In fact, in leaves that do not accumulate flavonoids, PTGS of DvCHS2 was detected (Ohno et al., 2018b). Therefore, this color lability of ray florets in ‘Yuino’ can be interpreted as a switching of DvCHS2 PTGS in SAM, and a candidate model of the SAM state for each inflorescence coloration is hypothesized (Fig. 2). When red ray florets occurred within an inflorescence, they were always located in the outer whorl of the bicolor ray florets, and the reverse pattern was never observed. This indicates a clear directionality of SAM status from red ray florets to bicolor ray florets. Considering the strong link between the color of ray florets and leaf flavonoid accumulation, we could define the SAM state of single-colored ray florets and flavonoid accumulating leaves as a “switch OFF” of DvCHS2 PTGS, and the SAM state of bicolor ray florets and non-flavonoid accumulating leaves as a “switch ON” of DvCHS2 PTGS (Fig. 2A). Therefore, when SAM maintains the “switch OFF” state, the inflorescence will be a single-color, whereas when SAM maintains the “switch ON” state, the inflorescence will be bicolor. If SAM maintains the “switch ON” state in a sector, the inflorescence will be mixed with sectorial single-colored ray florets. If the switch turns “ON” after the formation of outer whorl ray florets, the inflorescence color will be mixed, with single-colored ray florets in the outer whorls (Fig. 2B). Here, perhaps an epigenetic factor may be involved in this switch control because a seasonal effect was observed in which single-colored ray florets were more likely to appear in summer. Further research is needed to clarify this phenomenon.

Candidate model for the SAM status of DvCHS2 PTGS switching for ray floret color lability in ‘Yuino’. A: Relationship between SAM status and ray floret color and leaf flavonoid accumulation. When DvCHS2 PTGS is in the “OFF” state, single-colored ray florets and flavonoid-rich leaves are formed, and when DvCHS2 PTGS is in the “ON” state, bicolor ray florets and flavonoid-poor leaves are formed. B: SAM status and inflorescence coloration. When the SAM state is “OFF”, inflorescences with only single-colored ray florets are formed, and when the SAM state is “ON”, inflorescences with only bicolor ray florets are formed. When the SAM state is “ON” in a sector, mixed inflorescences are formed in which single-colored ray florets occur in that sector in the inflorescence. When the SAM state switches from “OFF” to “ON” after formation of outer whorl ray florets, mixed inflorescences with single-colored ray florets in the outer whorl and bicolor ray florets in the inner whorl of the inflorescence occur.

In this review, the flower color in dahlia is classified into the following types and major pigments as follows:

Ivory white: flavones

Purple and pink: anthocyanins and flavones

Yellow: 6′-deoxychalcones and flavones

Red and orange: anthocyanins, 6′-deoxychalcones, and flavones

Black: anthocyanins (some rare cultivars accumulate flavones)

Bicolor: colored basal part with white tips where there are no pigments

Variegation: ray florets with purple or red variegation

In summary, genes that determine flower color in dahlia are thought to be as follows: the bHLH transcription factor DvIVS determines the presence and amount of anthocyanins, and the aldo-keto reductase DvAKR1 determines the presence and amount of 6′-deoxychalcones. A transposon-inserted allele of DvIVS contributes to variegation. The PTGS of DvCHS2 contributes to bicolor formation and the PTGS of DvFNS contributes to black coloration in ray florets (Fig. 3). Lawrence and Scott-Moncrieff (1935) proposed that four genetic factors control dahlia flower color: A (light anthocyanin), B (heavy anthocyanin), I (ivory flavone) and Y (yellow flavone). It is assumed that factor A corresponds to a weak DvIVS allele, factor B corresponds to a strong DvIVS allele, and factor I corresponds to a non-functional DvIVS allele. Factor Y may correspond to DvAKR1. Characteristically, most of these colors are controlled by transcription factors or PTGS. This may be due to the high polyploidy of dahlia, in which several alleles and/or loci are regulated at the same time. Our findings will be helpful for developing molecular markers for flower color. Since dahlia is a high polyploidy plant, molecular markers will be a more powerful tool for breeding new cultivars than diploid plant species.

Candidate genes determining flower color in dahlia.

The origin of D. variabilis remains unclear and there are several theories: one of the two ancestors may be D. coccinea, while the other is more likely (Hansen and Hjerting, 1996; Saar et al., 2003) or less likely (Gatt et al., 1998) to be D. sorensenii. D. coccinea has long been recognized as one of parents of D. variabilis because it is the only species to produce yellow through to blackish scarlet pigments (Saar et al., 2003). Currently, a genome project for D. variabilis ‘Edna C’ is in progress with support from the American Dahlia Society (https://www.dahlia.org/genome-overview/, personal communication), so the genomic data will be available soon. The production of genetically modified dahlia plants is already possible (Otani et al., 2013a, b). Therefore, the whole genome sequencing of dahlia will not only lead to the identification of pigment biosynthetic genes and elucidation of the unstable pigmentation mechanism, but will also clarify the origin of flower color in garden dahlias.