2019 年 2019 巻 96 号 p. 179-229

2019 年 2019 巻 96 号 p. 179-229

Modern strong countries rely on innovation and technology transfer for their economic development. Governments see innovation as a strategy to advance, and have given priority to innovation policies, and actions.1 These policies mainly rely on facilitating and regulating the flow of knowledge and technology among the multiple actors in the innovation system – notably among universities, governmental agencies, and industry.2 This special flow is referred to as Technology Transfer, and is considered crucial for economic growth.

Recognizing the importance of innovation and technology transfer for its development, the World Intellectual Property Organization ("hereinafter WIPO") has adopted an initiative to support developing countries have a strong technology transfer systems, by establishing Technology and Innovation Support Offices (TISCs) in universities and research institutes with the main objective to provide know-how at the local level and use and extract value from the information contained in the IP databases.

The Arab Republic of Egypt ("hereinafter Egypt") has also given this topic special attention, and has formulated its sustainable development strategy "Vision 2030", with the objective to create an "innovative society producing science, technology, and knowledge". It has already made great steps in establishing Technology Innovation Commercialization Offices (hereinafter "TICO"), and has closely cooperated with WIPO in this regard. However, despite the tremendous efforts done by the Egyptian government, some challenges still remain, especially in relation to the commercialization of university research results.

This paper aims at showing the efforts done by Egypt in this field, and at addressing some of the challenges it currently faces, and at offering solutions to these challenges, by looking into the Japanese situation. Japan has used technology transfer to get out of its economic crisis in 1990s and has a lot of lessons to share. The research will conclude by offering collaboration possibilities with Japan where both countries can enjoy a relation of mutual benefit.

To address the previously mentioned research question, this paper will begin by elaborating how technology transfer is important for economic growth, and how WIPO is supporting developing countries in such area. Then it will continue to explain the Egyptian situation by showing the most recent developments and the challenges. Then this paper will look into the Japanese technology transfer situation in order to look for answers, before concluding by suggesting cooperation possibilities with Japan.

Japan has been chosen for this analogy, as it did not have an IP culture before that time. It made a lot of reforms and legal reconstructions to benefit from the concept of technology transfer and is still making constant legal amendments to cope with any new issue that arises. This situation is more similar to Egypt. Until recently, IPRs were only associated with negative connotations such as expensive drugs. Using IPRs for development is a relatively new concept. Moreover, Japan's SMEs are very strong and have a strong culture in R&D and in collaborating with universities. Japan has a lot of expertise in such field and can be a good role model for Egypt.

The methods used to achieve such results include the analysis of existing legal literature comprising articles and books related to innovation, intellectual property law, and industry-academia collaboration. In addition, this analysis also relies on conducted interviews with professionals working at the universities' technology transfer offices in Egypt and Japan, as well as on interviews conducted at WIPO on how it is helping developing countries with the industry-academia process and all the initiatives it is offering in this regard.

Modern strong countries are characterized as knowledge economies that rely on innovation and intangible assets such as patents and know-hows for their development rather than on physical abilities and tangible goods. A country's ability to create, organize, and disseminate knowledge and convert this into an economic and social good gives it a competitive advantage in economic growth. Possession of knowledge alone is not sufficient. It is innovation that creates new knowledge from existing ones and also new products and services.3

Important foundations of a knowledge economy are places where knowledge is created. These include academic institutions, such as universities, research centers, and laboratories, and companies engaging in research and development activities.4

Universities and research institutes constitute a vital source for the dissemination and diffusion of knowledge and the creation of innovation.5 Industries, especially Small- and medium- enterprises (hereinafter "SMEs") are the backbone of most economies, as they account for a very large percentage of employment in the industrial sector and play an important role in development. They are mostly seekers for the technologies created at universities. Governmental Agencies are the coordinators and supporters of this correlation.

The World Bank also states that, "Collaboration between academia and industry is increasingly a critical component of efficient national innovation systems.6 In addition, when linked to industries, universities "spin-off new technologies, products, and even new industries."7

This special linkage and collaboration between the academia and industry is referred to as technology transfer. It can be defined as the transmission or dissemination of research results from a university or research organization to a company or an industry. It is best described as a bridge that bonds the academia to the industry.

The Association of University Technology Managers (hereinafter "AUTM") defines technology transfer as "the process of transferring scientific findings from one organization to another for the purpose of further development and commercialization."8

University technology transfer contributes significantly to technological innovation, job creation, and research income. Furthermore, the translation of academic research into technologies that can be commercialized will generate a significant return on investment for local, national, and global economies. It also adds to jobs through the creation of economic opportunities (startups) through licensing of university invented technologies.9

The former figure shows the different patterns of technology transfer. The first one is a license of intellectual property rights and/or know-how which are research achievements of university, second one is an assignment of IP from university to industry, and the third one is technology transfer through collaborative research and technical guidance. These three forms of tech transfer can be regarded as concrete embodiments of industry-university collaboration.10

Recently, the World Intellectual Property Organization (hereinafter "WIPO") has adopted the notion of knowledge e transfer. On its website, WIPO explains that technology transfer concerns the transfer of innovative solutions that are protected by different intellectual property rights. Knowledge transfer is a broader term and covers other areas of research, including social sciences as well as less formal transfer mechanisms.11

IP Law and Technology TransferTo have a solid and efficient technology transfer system, policies, rules, and regulations must be present to regulate the relations between parties. Matters of IP ownership are of special importance. They are actually regarded as among the most powerful instruments available when increasing incentives for the commercialization of inventions.12 In addition, an intellectual property policy is the cornerstone of innovation and creativity for universities and public research institutions as it provides structure, predictability, and a framework for talented minds to do what they do best: innovate. Through R&D activities, universities and research institutions produce results in the form of inventions. Many of these inventions are patentable, yet many are also just proofs of concept or laboratory-scale prototypes, which require further R&D prior to possible commercialization. By granting universities the rights to their own IP derived from publicly-financed research and allowing them to commercialize the results, governments around the world are accelerating the transformation of inventions into industrial processes and products and are strengthening the collaborative ties among universities and industries.13

The issue of intellectual property ownership of publicly funded research has been of special importance to policymakers around the world. If a university or research institute conducts R&D activities with public funds, one should naturally expect those results to belong to the government or the public. Such practice, however, has proven to be hammering to the public instead of being beneficial. It is impossible to turn publicly owned research results into a commodity as companies and industries do not see any benefit in doing them.

The oldest and most famous legislation that came up with a solution to this issue is the "Bayh-Dole Act" (hereinafter "BDA") that was enacted in the United States in 1980. Named after US Senators Birch Bayh of Indiana and Robert Dole of Kansas, the BDA allowed small businesses and non-profit organizations (including universities) to retain the title to inventions made under federally funded research programs (AUTM 2013). Before the passage of this law, ownership was vested upon the federal government, which made technology commercialization more difficult. The 1980 enactment of the Bayh-Dole Act altered the intellectual property landscape with respect to patents and government-sponsored R&D.14

Beginning in the 1970s, there was growing concern about the apparent decline in the social value of public research in the United States as policymakers began to realize that innovations resulting from public-funded research were not reaching the marketplace.15 Thereafter until the 1980s, the US economy was in a severe recession. To overcome this, the US government decided to create mechanisms that would encourage researchers at universities and public research institutes to compete and undertake new and innovative research. The government then established mechanisms to encourage industry to actively utilize the research results by enacting the BDA in 1980 and among other laws that allowed laboratories to create networks for TT and to negotiate licensing, among other things.16

This pessimism over the recession prompted US lawmakers to seek institutional intervention. This was in the form of new legislations to promote industrial application, coupled with a smooth transfer of technologies generated from publicly funded research. It was with this vision that two consecutive legislations were passed in the United States in 1980. The first statute, Stevenson–Wydler Technology Innovation Act of 1980, made technology transfer an integral part of the R&D responsibilities of federal laboratories and their employees and It required federal laboratories to allocate budget for technology transfer activities.17

The second act was the BDA. The BDA explicitly obligated universities to file patent applications in the inventions that they owned, and they were entitled to retain ownership of any inventions created by federal funding, unless the funding agency informs the University up front that the agency will retain title due to specifically identified "exceptional circumstances" or other specified conditions.18

The requirements to retain ownership include, disclosing the invention to the federal agency within two months of learning of it, electing title to the invention by notifying the agency in writing within two years of disclosure, and filing a patent application on the invention within one year after election of title, or earlier if necessary to avoid forfeiture of patent rights.19

The BDA grants the government the privilege to "march in" and take control for patents that resulted from publicly funded R&D. In particular, march-in rights allow the federal government, in specified circumstances mentioned in section 203 of the law, to require the contractor or successors in title to the patent to grant a "nonexclusive, partially exclusive, or exclusive license" to a "responsible applicant or applicants." If the patent owner refuses to do so, the government may grant the license itself. The terms of the license must be "reasonable under the circumstances."20

In granting a license to use the invention, universities are required to give priority to small businesses, while maintaining the fair-market value of the invention. When granting an exclusive license, universities must ensure that the invention will be "manufactured substantially" in the United States. Excess revenue must support research and education and inventors must be given a share of the royalties.21

The World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) was established in 1967 as one of the 15 specialized agencies of the United Nations (UN), with the aim to "encourage creative activity, [and …] promote the protection of intellectual property throughout the world."22 It currently has 191 member states, administers 26 international treaties, and has its headquarters (HQ) in Geneva, Switzerland. The current Director General of WIPO is Francis Gurry, who took office on October 1, 2008.23

WIPO supports its member states, especially the developing countries and least developed countries (LDCs), in using intellectual property (IP) for their development through different programs and initiatives and in accordance with the "Development Agenda of WIPO" that was adopted in 2007 by its member states with the aim of placing development at the heart of the organization's work.24

WIPO supports mutually beneficial technology transfer through patent information services, innovation support programs and tools, projects and activities by WIPO committees, public-private partnerships (PPPs) and dispute resolution services, capacity building, and training on transfer of technology.25

On July 9, 2018, the author, with the help of Mr. Takao Ogiya, Executive Managing Director of the Asia-Pacific Industrial Property Center at the Japan Institute of Invention and Innovation (JIII), and Assistant General Yo. Takagi, who leads WIPO's Global Infrastructure Sector (responsible for its Access to Information and Knowledge Division), held a few interviews at WIPO's HQ in Geneva, Switzerland to learn more about these programs. The main activities supported by WIPO in the field of technology transfer will be presented below.

Technology and Innovation Support Centers (TISCs)In April 2009, WIPO was mandated by its member states to carry out a pilot project establishing technology and innovation support centers (TISCs) within the framework of its Development Agenda. The purpose of this project is to address Recommendation 8 of the WIPO Development Agenda, which requests that WIPO "[facilitate] the national offices of developing countries, especially LDCs, as well as their regional and sub-regional intellectual property organizations [in accessing] specialized databases " This project approved by the member states encompasses two core clusters of activities—specifically, access to specialized databases and capacity building.26 Since January 2014, the project has been fully incorporated within the regular activities of WIPO and is considered part of its program on Services for Access to Information and Knowledge.27

The TISC program significantly contributes to the further development of the WIPO Knowledge Network by providing value-added services and specialized platforms and tools for strategic knowledge and management.28

With the main objective of providing know-how at a local level and using and extracting value from the information contained in IP databases, the program facilitates the access to and the use of technological information, scientific and technical literature, search tools and databases, and capacity building in developing countries to effectively support innovation, technology transfer, and commercialization-related services by providing innovators with access to locally-based technology information and associated services.29

TISCs may be established within a variety of host institutions, including patent offices, universities, research centers, and science and technology parks. Now around 75 countries have local TISC offices, located in universities, science and technology parks, chambers of commerce, and industry associations.

Since January 2014, the project has become a regular WIPO program with full-time dedicated staff, a follow-up division, and reserve funds, and forms part of WIPO's program on Services for Access to Information and Knowledge.

Establishment of a local TISC office is easy. The only requirement is to have two people, a computer, and internet access to facilitate providing a service-seeker with information. This is because the main objective of the program is to help developing countries access and consult information, particularly data related to free patent databases such as those of the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) and Japan Patent Office (JPO).

WIPO has four categories of TISC offices, and has classified the 75 currently available offices into four maturity categories. The first category represents the most basic maturity level, which is mainly the establishment of the office and the provision of basic IP information. At this stage, only one TISC activity is anticipated. TISC offices at this level send reports to WIPO indicating how many users have come to the office or have benefited from its services. At this stage, the focus is more on creating a culture of IP and familiarity with the TISC concept.

At the second stage, more advanced services are expected. However, this level is still considered a basic one, where anticipated business includes patent drafting activities, providing professors with non-disclosure agreements, and the establishment of IP policies. All these activities are provided for free. The third stage of maturity relates to technology transfer activities and the ability of the office to provide training services to other staff members. The fourth and highest level of maturity involves the management of IP assets and IP valuation. This stage is where the office adds value to its services. Such activities include monitoring of competitors, patent protection strategies, commercialization, and technology monitoring. At this stage, TISC offices can request a fee for their services since they have added their input and knowledge.

WIPO provides the allocated TISC staff with practical training to administer the expected services, such as how to search the patent databases and use the search tools. These trainings are of short duration but have been proven helpful. Additionally, TISC staff can use free WIPO courses, such as the D101 series. WIPO does not approach a country to request the creation of a TISC office; in fact, it is the other way around. A country that desires to establish a TISC office or that needs a specific service or training reaches out to WIPO.

Additionally, for the improved establishment of the access to knowledge and information initiative, WIPO has also created the Access to Research for Development and Innovation (ARDI) program.30 This is a PPP that enables developing countries and LDCs to access scientific journals for a low subscription fee or for free. In this program, WIPO has played the role of a facilitator between big publishing companies and developing countries. Publishing houses agreed to offer this service for countries where they had no market. Countries with an already existing subscription base were not eligible to participate in this program. This is regarded as a mutually beneficial win-win situation for developing countries and publishing houses. Currently, over 100 publishers provide access to around 30,000 journals, books, and reference works for 120 developing countries and territories through ARDI.31

The same type of service is provided for commercial databases related to patent information through the Access to Specialized Patent Information (ASPI) program. This is a PPP administered by WIPO that was made possible through cooperation with leading patent information providers such as LexisNexis, for example. Through the ASPI program, eligible patent offices and academic and research institutions in developing countries can receive free or low-cost access to sophisticated tools and services for retrieving and analyzing patent data with value-added information.32

Furthermore, another service offered through TISC is the Inventor Assistance Program (IAP) 33, which is a free legal service provided to individual inventors seeking patent advice (including guidance on drafting, but not filing). However, this has only been implemented in 4 countries because it depends on the connections of the TISC office with its local bar association, the possibility of finding lawyers who can provide such services pro bono, and the capacity of the TISC office to investigate whether such individuals are of real need of the pro bono services offered.

Egypt's modern history is mostly characterized by its 2011 revolution. Following this event, the country fell into deep recession, its gross domestic product (GDP) decreased tremendously, foreign direct investments (FDIs) escaped the country, and tourism declined. Today, thanks to the significant efforts undertaken by the Egyptian government, the situation has improved intensely. The Egyptian government implemented major economic reforms that included the flotation of the Egyptian pound and new investment and taxation laws. The government also emphasized knowledge, innovation, and scientific research as a pillar of its development and reinforced the country's Sustainable Development Strategy, also known as "Egypt Vision 2030."34 In this regard, it highlighted the necessity of establishing a solid and efficient relationship between academia and industry to boost its economy and develop a knowledge-based one, particularly since Egypt has a competitive advantage in the information technology (IT) field.

Egypt's Vision 2030By 2030, Egypt aims to have "a creative and innovative society producing science, technology, and knowledge […] within a comprehensive system ensuring the developmental value of knowledge and innovation and using their outputs to face challenges and meet national objectives."35 This strategic vision for knowledge, innovation, and scientific research emphasizes accomplishing three main objectives, which are the creation of a stimulating environment for the localization and production of knowledge, activation and development of an integrated national innovation system, and linking knowledge applications and innovation outputs with priorities.36

In this regard, two main challenges are seen as particularly hindersome to this plan and are characterized as high impact and should thus be addressed. First, the legislative system is poor in motivating and protecting innovation, and second, there is insufficient coordination between social needs and innovation. In this chapter and while giving recommendations to improve the efficiency of the Egyptian system, these two challenges will be given priority. Before addressing them, Egypt's current legal framework and situation will be elaborated.

IP Legal Framework in EgyptEgypt is located in northeast Africa and enjoys a civil legal system where codified laws are the primary source of rule. This modern legal system was initially developed in the 19th century, was modeled after the French civil code system (the so-called "Napoleonic Code"37), and was first introduced during Napoleon Bonaparte's occupation of Egypt in 1798 and the subsequent education and training of Egyptian jurists in France.38 Egypt's supreme law is its written constitution that was last amended in 2014 in the aftermath of the Egyptian revolution of 2011.

For the first time in the history of the country, the new Constitution of 2014 expressly stipulated the protection of intellectual property rights (IPRs) in its Article 69, declaring that "The State shall protect all types of intellectual property rights in all fields, and establish a specialized agency to uphold such rights and their legal protection as regulated by Law."39

The main source of IP laws in Egypt is Law No. 82 for the Year 2002 (Law 82/2002). This law replaced a collection of laws dating back to 1939 with a comprehensive intellectual property code as part of an effort to bring Egypt into compliance with its obligations under different international agreements.40 Law 82/2002 generally attempts to mirror the provisions of the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS).

Egypt is party to most IP treaties41 and is currently working on accession to the "Marrakesh Treaty to Facilitate Access to Published Works by Visually Impaired Persons and Persons with Print Disabilities" (MVT), which relates to copyright law and facilitating access to published works to visually impaired people. Accession has already been discussed in the Egyptian parliament and is expected to be incorporated into law in the near future.

Egypt's IP code is divided into 4 chapters, officially called "books," and each book deals with one branch of IP. The new code addresses matters related to patents, integrated circuit designs, undisclosed information, trademarks, geographical indications, trade statements, industrial designs, copyright and related rights, and plant variety protection.

Ownership Regulation in Egyptian Patent LawMatters related to patent ownership are regulated in Articles 7 and 8 of the Egyptian patent law, Law No. 82 of 2002 on the Protection of Intellectual Property Rights.42 The law stipulates that "The employer shall have all the rights derived from the inventions discovered by the worker or the employee during the period of work relationship or employment, insofar as the invention falls within the scope of the work contract, relationship or employment. The name of the inventor shall be mentioned in the patent, and he shall be remunerated in all cases. If such remuneration was not agreed on, he shall be entitled to a fair compensation from the person who requested the invention, or from the employer."43

Additionally, the law states that "In cases other than the preceding, where the invention is part of the activities of the public or private establishment to which the inventor is attached, the employer shall have the choice either to exploit the invention, or to acquire the patent against a fair compensation paid to the inventor, provided the choice is made within three months from the date of notifying the grant of the patent. In all cases, the invention shall be attributed to the inventor."44

Article 8 declares that "The application for patent filed by an inventor within one year from the termination of his employment in a private or public establishment […] shall be considered as filed during the work or employment contract. Both the inventor and the employer shall be entitled to all the rights stipulated in the preceding article, as appropriate. Such a period shall extend to three years if the said worker establishes or joins a competing establishment and the invention is the direct result of that worker's activity and previous experience in the establishment in which he was working."45

Regardless of these two articles, when it comes to technology transfer from universities to industries and the ownership of publicly funded research, there is no explicit law regulating these matters. They are decided on a case-by-case basis and in accordance with the policy of the governmental funding agency.

The Current Technology Transfer SystemThe real start of technology transfer in Egypt occurred in 2010 through a European project called the Trans-European Mobility Programme for University Studies (TEMPUS). This project was designed to bridge the gap between research and industry by trying to bring research and innovation out of academia and into industry. It comprised only four Egyptian university-based offices (American University in Cairo, Cairo University, Assiut University, and Helwan University) These TTOs supported research at all stages of technology implementation, from an idea to an invention, through the process of intellectual property protection, setting up a company, and the full-on commercialization of intellectual property.46

In 2013, with the objective to advance innovation and the knowledge economy of Egypt, the Egyptian Academy of Scientific Research and Technology (ASRT), which is under the Ministry of Higher Education, along with the Egyptian Patent Office launched a national initiative called TICO to strengthen the link between scientific research and industry and to promote the protection of intellectual property.

Technology Innovation Commercialization Offices (thus the name "TICO") were created at universities, research institutes and governmental departments with the objective to activate and support the role of universities, research centers, research and developing centers at serving the industry and support the scientific management of these offices. In addition, the initiative also aims to support the industry, agricultural and services communities effectively in order to build trust and reach to the active partnerships with the scientific research through mutual interaction.47 This initiative was adopted in correlation with the WIPO's TISC program.

Each TICO is structured in three complementary parts: grant and international cooperation offices (GICOs), which provide information about funding opportunities and support grant writing training; technology and innovation support centers (TISCs); and technology transfer offices (TTOs), which operate as technology incubators, liaise with industry and university, and offer expert advice on licensing agreement negotiations to universities, SMEs, and start-ups.

Starting with 24 offices in 2013/2014, Egypt has currently 43 offices supported financially by the ASRT with a total amount of 30.100.000 EGP (1.680.766 US$) L.E. with 700.000 EGP (around 39.087 US$) for each office49. Out of these 43 offices, 20 offices have finished the first stage and are now in the second maturity stage according to the definitions designated by WIPO's TISC. The ASRT is expected to offer financial support for the second stage as well. The ASTR follows up on all TICO activities and asses the offices on a quarterly basis. Those who achieve well, are eligible for the second stage. ASRT also offers support and advice to any local TICO office that desires so.

The ASRT took many steps in raising awareness about technology transfer in universities and research institutes, and has positively impacted the innovation ecosystem in Egypt. For the first time, protection of IPR created at universities became a priority for professors, and even though publication is more important in Egypt, professors started to file for patents before publishing. Moreover, some universities started to reach out to the industry to commercialize their research results and started to look for other cooperation models.

One of the successful examples for reaching out to the industry is the TICO office at Egypt-Japan University of Science and Technology (E-JUST). Even though this office is relatively small, it managed to reach out to the industry and to commercialize several technologies developed by its professors. This office was successful because its personnel is very aggressive in contacting the industry and is always reaching out to the ASRT for advice and help.

In addition, ASRT encouraged universities to draft IP policies and universities were offered training on how to do so. Training in this field was held in cooperation with WIPO and universities who managed to draft their IP policies were given higher evaluation points and were eligible for the second stage of the TICO program.

However, it was noticed that the success rate of a TICO at small and medium size universities and research institutes, was higher than at bigger ones. This is because at those universities it was easier to create trust between faculty members and a TICO office. In addition, big universities already collaborate with the industry, mainly in the form of short term technological consulting, and it was more difficult to convince the professors of a wider cooperation forms.

Moreover, to strengthen TICO and make it easier to trust, ASRT started offering a lot of training to the personnel of the TICO offices, in connection with WIPO and TISC. This includes general IPR knowledge and, patent search trainings, as work of TICOs necessitates high caliber individuals with strong knowledge of IP, market and technology trends. This is a promising step from ASRT, as most of the TICO personnel have only an administrative background and lack legal or business skills.

Looking on this, It is easy to recognize all the efforts, and achievements done by universities in this field and how much the IP and technology transfer culture has easily spread. However, when it comes to industries, the situation is different. The majority of factories and Egyptian SMEs still do not have this culture and do not work with academia unless there is external funding or foreign grants. SMEs are still reluctant to invest from their own budgets. Nevertheless, factories/SMEs choose to work with academia if academic researchers can provide a cheaper local substitute to what is imported for production. At this stage in Egypt, only cost savings make factories willing to invest in a collaboration with academia. The most common case is R&D for finding a local alternative solution that will provide the same function as the imported one.50

After the devaluation of the Egyptian pound, many factories were left with a rapid and major increase in the cost of the raw material they imported. If local alternatives are available, factories will invest in them. Only short-term consultancy projects exist at the present and have a high success rate. It is standard and common for university professors to work as consultants for industry. Faculty of Engineering Professors in Egypt have a good reputation as consultants for the industry. To start boosting industry-academia collaboration, it is recommended to first look into the needs of the industry to identify the current requirements that do not necessitate long-term R&D investment and find academic researchers to address those needs. Industry requirements could mainly ask for adjustments rather than new technologies.51

The Ministry of Industry tried to increase this collaboration and has therefore created its own technology centers. Around 12 centers were created and located in different industrial clusters with the aim to offer technical assistance to the SMEs situated there.52 However, not all centers were equipped with high technologies that can respond to the needs that arise.

However, to boost technology transfer and innovation in Egypt, challenges related to the lack of appropriate legal framework should be given priority. As for the laws related to technology transfer in Egypt, and as previously shown, regardless of the ownership stipulation in the Egyptian IP law, Egypt does not have legislation governing TT. There is no law similar to the BDA. What does this mean for Egypt? Public funding agencies are the sole owners of research results in Egypt, and even if they decide to give such ownership to universities, when public universities commercialize their technologies, the general rules of bidding apply. As a result, universities must engage in open-bidding and advertise the technologies in the national newspaper, and they are bound by laws requiring them they sell at the highest price regardless of other conditions. How is that possible with the nature of technology transfer, where privacy and non-disclosure are important factors to those interested in the technology? Also, this rule means that one must disregard the different types of licensing.53

In addition, laws governing universities do not allow them to create spin-offs or to own shares in private companies. This should change to promote technology transfer, as the creation of spin-offs and start-up is one of the main forms of TT, and is gaining a lot of popularity in recent years. Additionally, when it comes to royalty-sharing from licensing, IP law only mentions "fair compensation" to the inventor. There is no specific percentage distribution stated in the law. Instead, this is negotiated on a case-by-case basis.

In order to find solutions for those challenges, this paper will look into the Japanese situation to see how Japan has used tech ology transfer legislation to address its economic crisis and how Egypt can learn from that.

In the 1970-1980 period, Japan was enjoying a rapidly booming economy. This was because at that time Japan was successfully mass producing and globally marketing uniform products.54 In the 1990s, however, the "bubble burst" as developing countries began to produce cheaper products and the Japanese economy plunged into a deep recession. This period is also referred to as the lost decade wherein Japan began losing its competitive edge against developing countries.

Working to get out of stagnation and searching for measures to revive its economy, the Japanese government decided to study the American situation to see how the United States helped itself out of its eighties depression. By reviewing US legislations from the eighties and early nineties, Japan's Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) was convinced that intellectual property-related legislations encouraging technology transfer were the primary reason for the recovery of the United States from the recession and that it has used universities as a strategy to recover from depression.55 Following the successful examples of the United States, Japan launched a program to exploit universities in an effort to recover from the post-bubble economic depression. Specifically, the country initiated university reform programs with a focus on the Approved Technology Licensing Organization (hereinafter "TLO") System in 1988 and the Japanese version of the BDA in 1999.56 The government also implemented a rapid series of measures to encourage industry to utilize the research conducted by universities and public research institutes.57 Japan was convinced that to promote a sustainable development in the 21st century, it has to shift from being a mere manufacturing economy to being an intellectual property-oriented society.58

In 2002, then Japan Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi was the first to declare that Japan would establish itself as a country based on intellectual property (an "IP-based country"), placing IPRs as a mainstay of the country's policy.59 In this regard, the government adopted a series of reforms aiming to create technology transfer offices to bridge research with industry and bring university inventions into praxis.

Universities in Japan were changing their role from being only academic institutions offering conventional education and research to offering their research results to commercial or industrial use. This, of course, also required legislative changes covering universities.

The government pushed through with the Act on the Promotion of Technology Transfer from Universities to Private Business Operators (commonly known as the TLO Law) in 1998, Industrial Technology Enhancement Act in 2000, and Intellectual Property Basic Act in 2000. Furthermore, an Intellectual Property Strategy Headquarters was established in the cabinet to be the mediator between the different ministries. It also included members from the private sector and is responsible for creating the country's general intellectual property policy and supervising its execution.

To suggest a legal framework for technology transfer in Egypt, the main laws and regulations relate to technology transfer in Japan will be briefly introduced. While Japan has many laws regarding this, the unique thing about the Japanese situation is having a set of laws that cover all aspects of technology transfer and that are in efficient harmony.

Chronologically speaking, the first law that was enacted in this regard is the "Science and Technology Basic Act" of 1995 which is considered the foundation of the Japanese science and technology policy. This law established the fundamental framework for future policy on the effective promotion of science and technology. The law also aimed at enhancing and ameliorating the environment for the basic and creative research and development in Japan.60

Therefore, its objective is to achieve a higher standard of science and technology, to contribute to the development of the economy and society of Japan.61 The Science and Technology Basic Law also introduced the promotion of science and technology through effective collaboration of universities with other universities and the government under a basic framework. Science and technology efforts are based and regulated by 5-year Basic Plans, which are drafted according to the principles contained in the Basic Law.62

In 1998, the Japanese government enacted the "Act to Facilitate Technology Transfer from Universities to the Private Sector" (Act No 52 of 1998, hereinafter "TLO Act"). As it explicitly states in its Article 1, the law aims to "contribute to the facilitation of the transformation of the Japanese national government's industrial structure, to the sound development of the national economy, and to the advancement of learning, as a result of efforts to develop new fields of business, improve industrial technologies, and revitalize research activities at universities, national colleges of technology, inter-university research institutes, and national research and development institutes, etc. through measures to promote the transfer of research results related to technology to the private sector."63

The law stipulates that the government will support the establishment of TLOs engaged in the transfer of research results developed by universities or governmental testing or research agencies to private business operators and will provide assistance to speed up this type of technology transfer.64 As such, one can say that this law allowed a new beginning for the cooperation between universities, inventors, and industries. It defined the cooperation we know today.

In 1999, the Japanese government adopted the Act on Special Measures for Industrial Revitalization, which is considered the Japanese version of the BDA to regulate ownership of publicly funded research. The objective of this law is to revitalize research activities connected to technology and use efficiently these results in business activities.65 To enable this, the law gave universities the patent ownership rights whenever government funds were used for research, giving big incentives to inventors. Before its enforcement, all research results using government funding were owned by the government66 and were difficult to commercialize. Therefore, universities were finally allowed to own all IPRs arising from a governmental research fund.

However, for universities to acquire ownership according to this law, three conditions must be fulfilled. First, universities and research institutes must report the inventions to the government right after a researcher makes a disclosure. Second, universities have to agree to grant the government a royalty-free license to obtain information on the subject matter in case public interest on it arises. Third, universities are obliged to give license to a third party in the case of a non- exploited subject matter explicitly stated by the government as a necessity.67 One exception to this ownership rule is the case of international research projects where foreign governments or non-profit organizations collaborate with Japanese contractors.68

As universities now are required to manage their patents, they establish internal organizations that manage everything related to patents such as filing and management.69

In a comparison conducted by Prof. Toshiko Takenaka from the University Of Washington School Of Law in 2005 between the American and Japanese versions of the BDA, she explains that even though both have the same main function, they have different scopes.

The scope of the Japanese BDA is actually broader and does not only cover patents but also other IPRs such as utility models, design registration, and copyrights. This is why those regulations were not incorporated in the patent laws but in industry laws.70

In Japan, private universities outnumber national universities. However, the former are regarded as leading academic research. This is because more resources are allocated to higher education and research and are expected to have a more valuable knowledge input to science and technology.71

Until March 2004, Japanese national universities were part of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (hereinafter "MEXT") and thus they were considered a branch of the national government and were fully operated by it.72 On April 1, 2004, national universities were given an autonomous legal personality and acquired the status of "national university corporations." This reform was regarded as one of the most noteworthy restructurings of Japanese universities since the beginning of the modern higher education system.

This reform meant that many government ordinances such as accounting rules or asset management were lifted, and universities had a bigger discretion and a higher freedom of action. This law also clearly states that national universities can now conduct funded or cooperative research, share research results, and freely use these results, the law also allowed universities to invest in organizations specializing in university technology transfer.73

This reform was, however, not positively received by the academia as it meant faculty members of national universities had to lose their status as government officials. However, being a government official in Japan restricts dealing with the private firms, a matter that makes technology transfer and joint research impossible. Therefore, this amendment was vital in putting the collaboration between academia and industry into action.

With the enactment of this law, university faculty member were no longer governmental officials but regular employees who can own patents or have their rights assigned to patents.74

Universities were required to develop the rules for employees' inventions and set up an intellectual property department to manage IPRs at the university. MEXT even granted subsidies for setting up the department in addition to the existing subsidies (funded by the Japanese government to universities for university administration).75

Universities that had already established a TLO before becoming a corporate entity would cancel the TLO to acquire it within the university, sign an agreement with the existing TLO to contract services, or buy all shares of the TLO to make it a wholly-owned subsidiary as done by University of Tokyo. The late enactment of this law caused the creation of two different organizations (Intellectual Property Department and TLO) engaging in a similar business, and the confusion could have been somewhat avoided.

Now that university professors have become regular employees, the IP ownership regulations of Article 35 of the Japanese patent law, were applicable. Modeled after the German system and revised in 2015,according to the new amendments, employee's invention belongs to the employer. This is under the condition that the employer makes a prior agreement with the employee that in case of an "employee invention" (i.e., an invention made within his work duties), the ownership of the patent right shall inherently be vested in (i.e., shall inherently belong to) the employer.76 In other words, the patent belongs to the employer from the time of its existence, under the condition that the contract, the internal work rules, or any other agreement with an employee-inventor on employee inventions provides so in advance.77 As a consequence, this amendment does not mean that the right to obtain a patent belongs systematically to employers. If a company fails to have a contract or employment regulation regarding employee inventions, then the employee retains his right to the patent as before the amendment.78

Another major amendment with regards to employee's invention is related to the reward received for the employee's invention (now Article 35, paragraph 4). With the new amendment, the reward is not only monetary but can also take any form of "reasonable [..] economical profits," such as a promotion or an overseas study program. The Japanese legislative body is aiming to reduce the employee-employer litigation with this new adopted rule and consequently increase the quantity and quality of technical innovations made by businesses.79

The new amendment also stipulated that the criteria for the reasonable monetary reward or other economical profits must be determined in accordance with the guidelines set by the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry. Those regulations, however, are related to the decision-making procedure for determining what is to be regarded as a reasonable monetary or other economic benefit, and not do not mention the details/specifics of the reasonable amount of monetary profit.80

The Intellectual Property Strategy HeadquartersWith the aim to create an intellectual property agenda for patents and other aspects of intellectual property, and based on the Intellectual Property Basic Act of 2002, the Intellectual Property Strategy Headquarters was established in 2003. Its objectives are carrying out the development and promotion of the intellectual property strategic program of the whole government and the planning, promotion, and comprehensive adjustment of important measures related to intellectual property.81

The Intellectual Property Strategy Headquarters is set up in the Cabinet to act as an intermediary between the different governmental ministries and to play the central role in facilitating relevant policies.82 It is in charge of the planning, annual follow up, and the revision of the intellectual property strategic plan.83

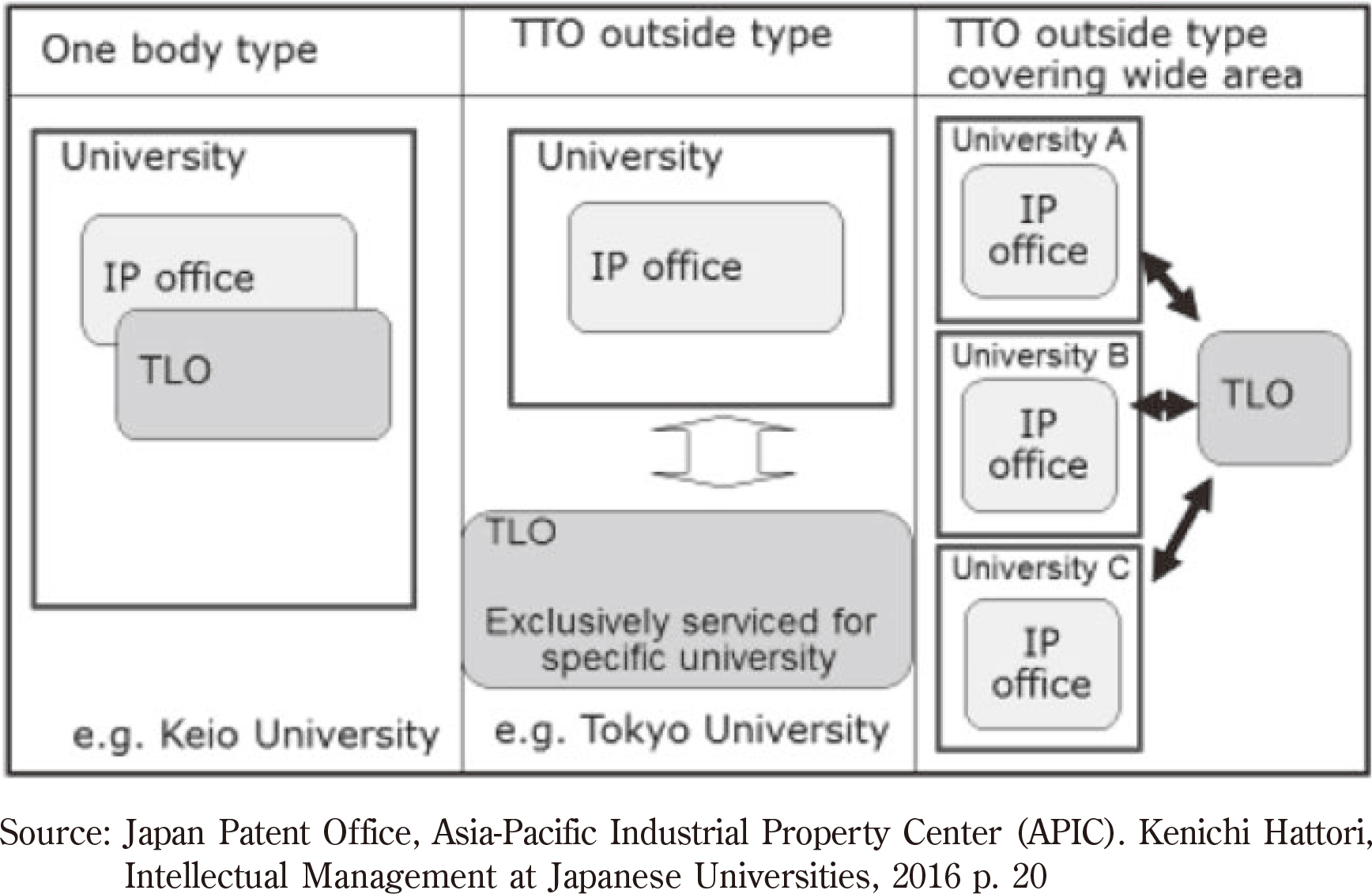

Technology Transfer OfficesLooking at the units that operate technology transfer In Japan, there are three different kinds of technology transfer offices as shown in the following figure.

Since the enactment of the TLO Law in 1998, a number of TLOs have been set up within or outside Japanese universities and public research institutes. Depending on the type of relationship between a TLO and its affiliate-university or universities, TLOs are classified as either in-house (i.e., TLOs that are established as an internal organ of a university), affiliated independent, or TLOs established outside universities. Affiliated independent TLOs are further classified into dedicated TLOs working for specific universities on a one-on-one basis and inter-university TLOs working for multiple affiliated universities. In addition to universities, the National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology (AIST) and other former national research institutes have set up their own TLOs either in-house or as an external independent organ.84

A regional TLO, the Kansai TLO for example, has been created to support the licensing efforts of several entities and not just one and performs technology transfer activities on behalf of many universities or research institutes.85

The type of TLO adopted depends on the scope of services to be entrusted to it as well as other factors relating to the particular situation at the university or public research institute.86 Now that the Japanese practice has been elaborated, how Egypt can emulate it will be discussed.

This paper attempted to provide insight on how Egypt has been using Technology Transfer for its development and on how it should go forward to achieve the next stage of commercializing its research results. It tried to demonstrate the importance of university-industry collaboration to economic growth and development. The role research and universities play in boosting knowledge economies is undebatable in all jurisdictions regardless of culture, background, or the prevailing legal system. To this end, all countries have emulated the American approach and have produced their own version of the BDA, as it is clear how the act has enormously improved the commercialization of universities' research results and Innovation.

However, this paper has given a deeper look into the Japanese approach for inspiration, as Japan has a long efficient history in university-industry academia. What is different and unique about the Japanese practice is not just the enactment of legislation similar to the BDA, but the creation of a complete framework and dynamic that links the relationships between the different stakeholders. Japan has created an IP HQ that regulates all IP-related matters between the different ministries, has set forth an IP policy, and continues to observe the implementation of IP strategies. This is a unique unit that is certainly adding to the improvement of IP in Japan.

Today, Japan has around 35 technology licensing organizations (TLOs) that try to commercialize university inventions. However, due to Japan's shrinking population, the market for these inventions is consequently also declining. Japanese TLOs should change their local government-oriented strategy and start looking for new foreign markets. Following this suggested approach requires overcoming the language barrier. While Japanese universities have databases of their technologies which can be commercialized, these are only available in the Japanese language. One can hardly find any information in English or staff that is comfortable speaking in English. To create new opportunities and new markets, Japanese TLOs must change this. Amazon started a good initiative to help SMEs commercialize their products and will translate descriptions plus pack and export goods for no extra charge.87 This is an impressive experience and universities can consider finding

Additionally, many Japanese professors and TLO staff only regard America and Europe as potential markets and completely overlook Africa. They do not see the potential that African markets can offer them. Africa is developing rapidly and its rate of economic growth is positively increasing. However, it needs advanced, sometimes even basic, technologies that Japan possesses to solve some of its problems. If these two markets can be united, a mutually beneficial situation will be established. Egypt can help here as it has strong relations to Africa and is the bigger

Furthermore, to maximize university-academia cooperation and create more opportunities, Japan should widen its view on technology transfer and adopt the concept of knowledge transfer that involves social science, as well.

Regarding Egypt, after the revolution of 2011 the economy fell into a deep recession, GDP decreased tremendously, FDIs escaped the country, and tourism declined. Today, thanks to the significant efforts undertaken by the Egyptian government such as the implementation of a total economic reform plan that included the flotation of the Egyptian pound and new investment and taxation laws, the situation has dramatically changed.

Additionally, in carrying out Egypt Vision 2030, the Ministry of Education started its large TICO initiative to establish TTOs in 43 Egyptian universities and research institutions, and Egypt has been moving in the right direction ever since. It has achieved good outcomes, including small commercialization of university research results, and is making positive steps in connecting industry with academia. To enhance innovation and the technology transfer environment, Egypt issued a new decision that gives priority to accepting Ph.D. students with proposals related to addressing current prevailing industrial challenges. Egypt has also, through its embassies, requested all researchers living abroad to provide the government with their scientific research papers and granted patents to try to implement those new technologies in development when applicable..

While the efforts of its government and universities have been conducted at a good pace up to this point, Egypt should get ready for the next stage. To prepare for this next phase and overcome the challenges related to innovation, knowledge, and scientific research mentioned in its 2030 vision88, some recommendations will be offered.

According to this vision, Egypt would like to carry out legal reforms related to knowledge and innovation. It is suggested that Egypt begin with establishing a governmental department that is similar to the Japanese HQ. It is recommended that this HQ be part of the Prime Ministry to be able to supervise all the other ministries. This department should be responsible for setting national IP policies in accordance with Egypt's development plans and for overseeing their implementation. Egypt should also coordinate IP-related matters between the different ministries to achieve better outcomes. It should be noted that this institution or department was mentioned in the new amendment of the Egyptian Constitution; however, it has not yet been incorporated. Egypt could emulate the Japanese experience in establishing its HQ and note Japan's best practices when establishing its own.

As Egypt has a competitive advantage in the IT field, it should study and regulate current IP matters, such as the IP of artificial intelligence, and be prepared for it.

While, as previously mentioned, Egypt has one article in its IP law that regulates employee ownership, it would be better to expand upon this. For example, it is recommended that more details be provided regarding royalties, rewards, and so on. It is advised to follow the Japanese practice and change the "reasonable remuneration" stipulation to a more concrete expression with a clear mechanism to calculate it. It is advised to follow the "share factor" that takes into account the position of the inventor. When it comes to royalties, many professors in Egypt believe that part of these royalties should be for personal purposes. It is recommended, that the law clears this matter and explicitly elaborates that royalties should be for the lab and to promote research activities. It is also suggested to allocate a percentage of the royalties to TTOs to help them sustain.

Additionally, Egypt should look into ownership of publicly funded research. At this stage, it is regulated on a case-by-case basis and depends on negotiations by the offering agency. A clear law regarding this and addressing rights and obligations will make things more efficient. It is recommended that Egypt emulate the BDA to achieve higher commercialization success, since at this stage most of the research budget comes from the government. Here, it is recommended that Egypt follows the Japanese version of the BDA and not the American one, as it is wider and covers all sorts of IPRs and is not limited to patents.

It is also advised to follow the US approach and enact a law similar to the 'Wydler Technology Innovation Act' of 1980, that requires federal laboratories to allocate budget for technology transfer activities. For the Egyptian case, it is recommended to widen the scope of this law, and allocate budget for TT activities from any budget that comes to a university, whenever applicable.

Egypt should also look into its tenders' law that requires public entities to sell their assets via public auction to the highest bidder. This makes commercializing technologies very difficult, as explained earlier. An explicit exception should be granted for such cases. It is important to mention, that for Japan to solve similar matters, it gave Japanese universities more autonomy and a separate legal personality. This can be difficult for Egypt to emulate at this stage. Alternatives should be thought about.

Moreover, at this stage, Egyptian universities are prohibited by law from owning any companies or shares in companies. This hinders the creation of start-ups and spin-off. Egypt has a lot of potential in this area, as many people prefer to have their own businesses. A legislative amendment allowing the creation of start-ups will add to the innovation culture.

As most universities are also new to the concept of commercialization, it could be more efficient if the government created regional TLOs in charge of commercialization and kept the current TICO offices as focal points serving the world of academia. Already 43 TICO offices are operated in Egypt, yet their sustainability will be difficult as self-sustainment is not expected at this stage. Therefore, regional or central TLOs are the most favored approach. TLOs should be located near industrial clusters and their staff should be trained well on commercialization and technology marketing.

Moreover, incentives should be given to professors to engage in academia-industry cooperation. Similar incentives should also be granted to the industries. They may include tax deductions. Egypt should also educate industries, especially SMEs, about the benefits and importance of R&D and technology transfer activities for their development. In this regard, the German approach is highly recommended since it involves the SMEs building a culture of trust on a step-by-step basis. Since Egyptian SMEs still do not completely trust academia and do not fully comprehend the concepts of technology transfer and the environment of IP, the German approach is best to emulate. In addition, incentives should be offered to the industries that cooperate with universities. These may include tax reductions.

Egypt should continue cooperating with WIPO and explore all the services it offers. Furthermore, Egypt can introduce these services to the rest of Africa. From the report shown, many African countries do not cooperate with WIPO in such field. Africa has a competitive advantage in cultural heritage, and even in innovation, and is developing rapidly. Cooperating with WIPO in such field will advance the growth, especially that Egypt is a member of ARIPO and of the COMESA.

Egypt and Japan have many cooperation opportunities in the field of technology transfer. Egypt has a lot to learn from Japan. When it comes to technologies, Japan is very advanced and can help the Egyptian universities with research. Alliance between Japanese universities and Egyptian ones can be one of the cooperation methods. In addition, Japan has hands on experience on IP education and implementation. Egypt can use such experience when developing its own.

Japan has many technologies but due to the shrinking market and language barrier is facing challenges in commercialization. Egypt has an advantage in this. Egypt is a big market and a lot of personal have experience with language and translation, including Japanese language. A platform can be developed where Japanese universities upload their technologies and Egyptian SMEs can benefit from them. Egyptian TTOs can work as navigators and facilitators. However, the challenge of high prices should be tackled. Moreover, an international Technology Transfer network between Japan and Egypt can be created to share expertise and share information.

In conclusion, Technology transfer is a unique concept and is of special importance since it transforms research and science from their basic formats into practical applications that benefit society. In short, it bridges two worlds together. While monetary benefit from technology transfer is always a matter of importance, it should not be the only point of interest. It is best to consider technology and knowledge transfer for the additional role it plays in universities, as well as its role in society. Egypt has already made many positive steps in the right direction and is expected to excel at commercialization in the near future. The door is open to many cooperation opportunities with Japan and promising future is ahead of the two countries that already have strong cooperation.

1 Jofre, S. "Exploring the role of knowledge and technology transfer in innovation systems. In Proceedings of Triple Helix" IX International Conference: "Silicon Valley: Global Model or Unique Anomaly?" (Vol. IX). Stanford University Press, 2011 p. 3.

2 Grimpe Ch. And Fier H. (2010). Informal university technology transfer: a comparison between the United States and Germany. Journal of Technology Transfer, 35: 637-650.

3 Shahid Alikhan, R. A. Mashelkar, Intellectual Property and Competitive Strategies in 21st Century 2nd edition, Wolters Kluwer, Law & Business, 2009, p. 123.

4 Ibid.

5 Jan Piotrowski, What is Knowledge Economy, SciDev.Net, 2015, https://www.scidev.net/global/knowledge-economy/feature/knowledge-economy-ict-developing-nations.html

6 Jose Guimon, Promoting University-Industry Collaboration in Developing Countries (Innovation Policy Platform, OECD and World Bank), Jan 2013, p. 5.

7 Steven Collins, Hikoji Wakoh, Universities and Technology Transfer in Japan: Recent Reforms in Historical Perspective, The Journal of Technology Transfer, 2000, p. 21.

8 https://www.autm.net/autm-info/about-tech-transfer/about-technology-transfer/

9 Donald S. Siegel, Academic Entrepreneurship: Lessons Learned for Technology Transfer Personnel and University Administrators, World Scientific Reference on Innovation, May 2018, p. 5.

10 UNITT Japan https://unitt.jp/en/tlo/

11 http://www.wipo.int/about-ip/en/universities_research/ip_knowledgetransfer/

12 Dirk Czarnitzki, et al., The Influence of Patent Ownership Rights on Academic Invention: Evidence from a Natural Experiment, https://editorialexpress.com/cgi- bin/conference/download.cgi?db_ name = I

13 WIPO's website on Intellectual Property Policies for Universities

14 John R. Thomas, "March-In Rights Under the Bayh-Dole Act", Congressional Research Service, 2016 p.7.

15 A. Agrawal, R. Henderson, Putting Patents in Context: Exploring Knowledge Transfer from MIT, Management Science, 48 (1), 2000 p. 44-60.

16 Japan Patent Office, Asia Pacific Industrial Property Center (APIC). Kenichi Hattori, Technology Transfer by Public Research Organizations, 2010, p. 6.

17 R. Eisenberg, Public Research and Private Development: Patents and Technology Transfer in Government–Sponsored Research, Virginia Law Review, 82 (8), 1663-727, 1996, p. 2.

18 https://www.innovation.pitt.edu/resource/bayh-dole-act-at-a-glance/

19 Heidi s. Nebel, "10-month conversion deadline?? new Bayh Dole regulations a trap for the unwary", Mckee, Voorhees & Sease, PLC, 2018.

20 John R. Thomas, op.cit.

21 Website of the Innovation Institute of the University of Pittsburg, https://www.innovation.pitt.edu/resource/bayh-dole-act-at-a-glance/

22 Convention Establishing the World Intellectual Property Organization, signed on July 14,1967, Preamble, second paragraph, found on wipo.int.

23 https://www.wipo.int/tisc/en/background.html#hosting

24 https://www.wipo.int/ip-development/en/agenda/overview.html

25 https://www.wipo.int/patents/en/technology/index.html

26 Ibid.

27 https://www.wipo.int/tisc/en/background.html#hosting

28 https://www.wipo.int/edocs/pubdocs/en/wipo_tisc_report_17.pdf

29 Ibid.

30 https://www.wipo.int/ardi/en/

31 https://www.wipo.int/ardi/en/

32 https://www.wipo.int/aspi/en/

33 https://www.wipo.int/iap/en

34 Detailed information about Egypt Vision 2030 is found on the Cabinet's website at http://www.cabinet.gov.eg/English/GovernmentStrategy/Pages/Egypt%E2%80%99sVision2030.aspx

35 http://sdsegypt2030.com/economic-dimension/2673-2/?lang=en

36 Ibid.

37 https://egyptjustice.com/civil-law/

38 Mohamed S. E. Abdel Wahab, "An Overview of the Egyptian Legal System and Legal Research," Globalex, 2012, http://www.nyulawglobal.org/globalex/Egypt1.html#_Introduction

39 Full text of the Egyptian Constitution can be found at http://www.sis.gov.eg/Newvr/Dustor-en001.pdf

40 Protecting IPR Overseas: Resources for U.S. Businesses

41 Egypt's treaty membership can be found at https://wipolex.wipo.int/en/legislation/profile/EG

42 Full text of the IP law can be found at https://wipolex.wipo.int/en/text/126540

43 Law No. 82 of 2002, Article 7

44 Ibid.

45 Law No. 82 of 2002, Article 8

46 https://dailynewsegypt.com/2010/09/28/technology-transfer-offices-inaugurated-at-egyptian-universities/

47 Official website of TICO Imitative http://www.asrt.sci.eg/index.php/asrt-departments/tico

48 This figure is released by the ASRT and is only in Arabic. It shows the numbers of TICO offices currently in Egypt and their locations.

49 Official numbers can be found here http://www.asrt.sci.eg/images/tico/1e.pdf

50 Mr. Mohamed Kash

51 Based on the interview with Mr. Kash.

52 Information given by Mr. Mohamed Mazen, Ministry of Industry. Any misinterpretation of information is the sole liability of the researcher

53 Information from the interview by Mr. Kash. Any misinterpretation of information is the sole liability of the researcher

54 Kozo Kubo, "How to promote Industry-Academia Collaboration and Manage and Utilize Intellectual Property in Japan", Research On Intellectual Property, Osaka Institute of Technology No.15.16, March 2016, p. 16.

55 Toshiko Takenaka, Technology Licensing and University Research in Japan, International Journal of Intellectual Property - Law, Economy and Management, 2005, p. 3.

56 Japan Patent Office, Asia Pacific Industrial Property Center (APIC). Kenichi Hattori, Technology Transfer by Public Research Organizations, 2010, p. 6.

57 Ibid.

58 Kozo Kubo, op. cit.

59 Japan Patent Office, Asia Pacific Industrial Property Center (APIC). Kenichi Hattori, Technology Transfer by Public Research Organizations, 2010, p. 6.

60 Kazuo Saito, The Science and Technology Basic Law and the activities of the Japan Science and Technology Corporation, Journal of Information Processing and Management, 1997, Volume 40, Issue 2, pp. 113-122, p. 3, released April 1, 2001, Online ISSN 1347-1597, Print ISSN 0021-7298, https://doi.org/10.1241/johokanri.40.113, https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/johokanri/40/2/40_2_113/_article/-char/en

61 Cabinet Office, Government Of Japan http://www8.cao.go.jp/cstp/english/law/index.html

62 Luca Escoffier, Japan's Technology Transfer System: Challenges and Opportunities for European SMEs, EU-Japan Centre for Industrial Cooperation, April 2005, p. 7.

63 http://www.japaneselawtranslation.go.jp/law/detail/?id=2359&vm=04&re=02

64 Japan Patent Office, Asia Pacific Industrial Property Center (APIC). Kenichi Hattori, Intellectual Management at Japanese Universities, 2016, https://www.jpo.go.jp/torikumi_e/kokusai_e/training/textbook/pdf/64_Intellectual_Property.pdf

65 Yoshitoshi Tanaka, Tokyo Institute of Technology, Interview and documents handed on July 31, 2017.

66 Toshiko Takenaka, Technology Licensing and University Research in Japan, International Journal of Intellectual Property - Law, Economy and Management, 2005, p. 2.

67 Toshiko Takenaka, Technology Licensing and University Research in Japan, International Journal of Intellectual Property Law, Economy and Management, 2005, p. 4.

68 Japan Patent Office, Asia Pacific Industrial Property Center (APIC). Kenichi Hattori, Intellectual Management at Japanese Universities, 2016, https://www.jpo.go.jp/torikumi_e/kokusai_e/training/textbook/pdf/64_Intellectual_Property.pdf

69 Ibid.

70 Ibid.

71 Ichiro Nakayama, Patent Ownership and Rewards for Inventions in Japanese Public Research Organizations, Research Center for Advanced Science and Technology University of Tokyo, http://www.innovation.cc/news/innovation-conference/patents.pdf

72 Jun Oba, Incorporation of National Universities in Japan and Its Impact upon Institutional Governance, 2006, per prepared for the COE International Seminar, organized by RIHE, Hiroshima University on January 16, 2006, under the title of University Reforms in Eastern Asia: Incorporation, Privatization, and Other Structural Innovations, p. 2, https://home.hiroshima-u.ac.jp/oba/docs/incorporation2006.pdf

73 Ryuji Shimoda, Intellectual Property Management of National University Corporations, International Journal of Intellectual Property - Law, Economy and Management, 2005, Online ISSN 1349-4759, https://doi.org/10.2321/ijip.1.37, https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/ijip/1/1/1_1_37/_article/-char/ja

74 Robert Kneller, Invention Management in Japanese Universities and Its Implications for Innovation: Insights from the University of Tokyo, 2011 pp. 69-85.

75 Interview and documents handed by Prof. Takafumi Yamamoto CEO & President of Tokyo University TLO in August.

76 Seiwa Patent & Law, Naohisa Akashi (patent attorney) and Manabu Hirata (patent attorney), Revisions Made to the Japan Patent Law Relating to Employee Invention System (made effective on April 1, 2016) May 10, 2016.

77 Japan Intellectual Property Association, Takashi Suzuki, Amendment of Article 35 (employee invention) of the Japanese Patent Act. April 2005, http://www.jipa.or.jp/english/activities/others/pdf/150422JIPA-AIPLA%20Meeting.pdf

78 Ushijima & Partners, Outline of New Employee Invention System, March 29, 2016, https://www.ushijima-law.gr.jp/articles/20160329UP_Ushijima_Kageshima.pdf

79 Seiwa Patent & Law, Naohisa Akashi (patent attorney) and Manabu Hirata (patent attorney), op. cit p. 1.

80 Sonderhoff & Einsel, Hiroshi Morita, The Employee Invention in Japan, EU-Japan Policy Seminar, November 2016, http://www.eu-jp-tthelpdesk.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Hiroshi_Morita-Employee_Invention.pdf

81 Cabinet Office, Intellectual Property Strategy Promotion Bureau, The Intellectual Property Basic Act and National Strategy of Japan, August 2017 document handed during the Intellectual Property Co-creation course held by Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) on August 2017.

82 Hisamitsu Arai, Intellectual Property Strategy in Japan, International Journal of Intellectual Property Law, Economy and Management 1 (2005) 5-12, p. 5.

83 Hisamitsu Arai, op. cit.

84 Japan Patent Office, Asia Pacific Industrial Property Center (APIC). Kenichi Hattori, Technology Transfer by Public Research Organizations, 2010, p. 7. https://www.jpo.go.jp/torikumi_e/kokusai_e/training/textbook/pdf/Technology_Transfer_by_Public_Research_Organizations.pdf

85 Luca Escoffier, op. cit. p. 30.

86 Ibid.

87 https://asia.nikkei.com/Business/Companies/Amazon-opens-doors-to-100-markets-for-Japan-s-small-sellers

88 Egypt's Vision 2030 http://sdsegypt2030.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/4.-Knowledge-Innovation-Scientific-Research-Pillar2.pdf