2022 Volume 5 Issue 1 Pages 1-15

2022 Volume 5 Issue 1 Pages 1-15

Exporting manufacturers often choose both integrated and independent channels to sell a product in a foreign market. This is called dual distribution channels in foreign markets or dual export channels. The purpose of this study is to employ capability theory and examine the effects of two capability factors, namely export market orientation (EMO) capability and export entrepreneurial orientation (EEO) capability, on the choice to use dual export channels. This study also examines the moderating effects of cultural distance on the relationship between these two capability factors and the dual channel choice. Empirical testing was conducted using survey data collected from 196 industrial exporting manufacturers. The results show that exporting manufacturers with strong EEO capabilities are likely to choose dual channel instead of independent channels. Moreover, empirical evidence reveals that exporting manufacturers with strong EMO capabilities are less likely to choose dual channels, but cultural distance moderates its negative effects. The current study contributes to improving understanding of international channel management by identifying the driving factors of dual export channels.

The use of multiple distribution channels has become common in today’s business-to-business markets. Industrial manufacturers often use a dual channel system, which refers to the use of both integrated and independent channels to sell the same product (McNaughton, 2002; Sa Vinhas & Heide, 2015). Several studies have investigated antecedent factors that influence manufacturers’ decisions to use dual channels (Dutta, Bergen, Heide, & John, 1995; Kabadayi, 2011; McNaughton, 2002; Takata, 2019). Most existing studies are based on transaction cost theory (Coase, 1937; Williamson, 1975) and provide essential insights into dual channels. For example, they suggest that when a manufacturer’s product has high asset specificity, the manufacturer is likely to choose a dual channel system rather than an independent channel system. By using both integrated and independent channels, manufacturers can indicate that they can replace all independent channels with integrated channels if necessary; this can prevent distributors from behaving opportunistically and taking advantage of manufacturers (Dutta et al., 1995; Kabadayi, 2011). In other words, by choosing a dual channel system and highlighting its implementation, manufacturers can reduce transaction costs incurred as a result of opportunism on the part of independent distributors.

Although prior research employing transaction cost theory offers important findings, it arbitrarily assumes that manufacturers seek to constrain opportunistic behavior and save transaction costs. In fact, manufacturers in the real world often seek to exploit their organizational capabilities to create high value. Application of capability theory is an appropriate method to analyze this trait among firms (Langlois & Robertson, 1995; Madhok, 1997; Sharma & Erramilli, 2004). The capability theory argues that organizational capabilities determine organizational and channel structures. Several recent studies on dual channels have employed the capability theory and found that manufacturers’ market orientation capabilities and distributors’ sales capabilities influence the choice to use dual channels (Ishii, 2020; Takata, 2019). Thus, by highlighting the importance of capability factors, these existing capability-theory-based studies significantly contribute to the advancement of dual channel research. However, most of these studies focus only on domestic channels and neglect the assessment of distribution channels in foreign markets or export channels of distribution. Therefore, a critical question remains unaddressed: how do capability factors affect the choice to use dual channels in foreign markets?

To answer this question, it is important to consider the following two points: 1) entrepreneurial orientation capability possibly affects the dual channel choice, and 2) cultural distance plays a moderating role between strategic orientation capabilities and channel choice. Regarding the first point, it is necessary to examine not only firms’ market orientation capability, but also their entrepreneurial orientation capability1). Entrepreneurial orientation capability is a strategic orientation characterized by innovativeness, risk-taking, proactiveness, competitive aggressiveness, and autonomy (Jambulingam, Kathuria, & Doucette, 2005; Lumpkin & Dess, 1996). While market orientation capability emphasizes leveraging existing markets, entrepreneurial orientation capability emphasizes developing new markets. According to the concept of organizational ambidexterity (He & Wong, 2004; March, 1991), successful firms implement exploitation and exploration of market opportunities. As market orientation capabilities facilitate the exploitation of existing markets and entrepreneurial orientation capabilities facilitate the exploration of new markets2), the international marketing literature argues that it is critical for exporting firms to possess these two types of strategic orientation capabilities (Boso, Cadogan, & Story, 2012; Cadogan et al., 2016; Laukkanen, Nagy, Hirvonen, Reijonen, & Pasanen, 2013). Thus, it would be useful to consider both entrepreneurial orientation capabilities and market orientation capabilities, and examine their effects on the choice to use dual export channels.

Regarding the second point, cultural distance between home and host countries may moderate the relationship between strategic orientation and channel choice. Unlike domestic channel relationships, exporting manufacturers and local partners operate in different countries; therefore, there can be differences regarding their respective norms and values (Grewal, Saini, Kumar, Dwyer, & Dahlstrom, 2018; Hoppner & Griffith, 2015). Prior research reveals that such cultural differences affect firms’ behaviors, strategies, and performance (Armstrong & Yee, 2001; Bianchi & Saleh, 2010; Chung, Wang, & Huang, 2012). Therefore, cultural distance may influence the effects of market and entrepreneurial orientation capabilities. This suggests that the existing research findings obtained within the context of dual domestic channels cannot be directly applied to the context of dual export channels. In environments that are culturally more different, dual channels may be able to help firms better leverage their market orientation capabilities. Thus, considering this unique feature of international markets (i.e., cultural distance) would further advance our understanding of dual channels in foreign markets.

Consequently, this study investigates the respective effects of market and entrepreneurial orientation capabilities on the choice of whether to use dual channels in foreign markets. Furthermore, it examines the moderating role of cultural distance between home and host countries. By analyzing survey data collected from industrial exporters, this study reveals that exporting manufacturers with strong entrepreneurial orientation capabilities are likely to choose dual channels. Moreover, empirical evidence shows that exporting manufacturers with strong market orientation capabilities are likely to choose dual channels when transacting with culturally different countries. The current study improves the understanding of international channel management by identifying the driving factors of dual export channels.

Most existing research on dual channels employs transaction cost theory, and argues that transaction cost factors, such as asset specificity and uncertainty, influence dual channel choice. Among such prior studies, Klein, Frazier, and Roth (1990) and McNaughton (2002) examine dual channels in foreign markets.

Klein et al. (1990) collect survey data from exporting manufacturers and observe that several firms utilized both integrated channels (e.g., wholly owned subsidiaries and in-house export departments) and independent channels (e.g., local importers and foreign distributors) to export their products overseas. Klein et al. (1990) explore the factors influencing the choice to use dual channels. They consequently find that transaction cost factors such as asset specificity and uncertainty have no significant effects in this regard. Moreover, they suggest that they find the effects of transaction cost factors to be non-significant because of the low number of dual channel firms considered in their analysis.

McNaughton (2002) examines the antecedent factors influencing firms’ choice to use dual channels when serving foreign markets. He classifies relationship-specific assets into human and physical specific assets, and classifies environmental uncertainty into environmental variability and diversity. By analyzing data gathered from the software industry, McNaughton shows that software manufacturers’ choices to use dual channels are influenced by physical asset specificity, environmental variability, and environmental diversity.

The above studies utilize transaction cost theory and provide useful insight into export channel selection. However, as mentioned earlier, previous research in this area arbitrarily assumes that exporting manufacturers aim to reduce transaction costs by suppressing opportunistic behaviors; this overlooks the fact that real-world manufacturers often seek to create value by exploiting their capabilities. To overcome this shortcoming of transaction cost research, several studies employ capability theory (Langlois & Robertson, 1995; Madhok, 1997; Sharma & Erramilli, 2004) to address the topic of channel selection. The following section provides an overview of such prior studies.

Capability theory and channel selectionChannel-selection research employing the capability theory argues that management resources and organizational capabilities influence channel selection decisions. For instance, He, Brouthers, and Filatotchev (2013) and Pehrsson (2015) address the single channel selection problem: the question of how manufacturers, when employing a single channel strategy, choose to use either an integrated or independent channel. He et al. (2013) focus on export market orientation (EMO) capability, which refers to a firm’s ability to efficiently generate, disseminate, and respond to market information in the export market (Cadogan et al., 2016; Cadogan & Diamantopoulos, 1995; Cadogan, Kuivalainen, & Sundqvist, 2009). He et al. (2013) show that manufacturers with strong EMO capabilities are proficient at gathering market information that they choose integrated channels to directly interact with their customers. Meanwhile, Pehrsson (2015) focuses on export entrepreneurial orientation (EEO) capability in addition to EMO capability. He conceptualizes EEO capability as a construct composed of three dimensions: innovativeness, risk-taking, and proactiveness in the export market. Pehrsson (2015) reveals that amongst the three dimensions that constitute EMO capability, information generation has a positive effect on the choice to use integrated channels, whereas information dissemination exerts a negative impact. Moreover, he finds that of the three dimensions that constitute EEO capability, innovativeness and proactiveness positively affect the choice to use integrated channels.

While these studies focus on single channel selection in foreign markets, several studies employing the capability theory examine dual channel selection in domestic markets. Mols (2000) presents 11 propositions concerning antecedent factors affecting the choice to use dual channels; some of these propositions can be considered to be related to capability theory (Takata, 2015). Specifically, Proposition 2, which emphasizes the importance of accessing customer information, is related to market-orientation capabilities; and Proposition 3, which highlights the differences between qualified distributors in each region, is related to distributors’ sales capabilities. Based on a descriptive study by Mols (2000), Takata (2019) shows that among Japanese firms, market orientation capability and regional differences in distributors’ capabilities are positively related to the choice to use dual channels. Additionally, he shows that in the Japanese context, these two capability factors exert a more significant influence on the dual channel choice than transaction cost factors; this results from the long-term and group orientation that characterize Japanese firms’ operations. Furthermore, Ishii (2020) reveals that market turbulence enhances the effects of manufacturers’ and distributors’ capabilities on the dual channel choice.

Although these studies provide great insight into dual channels, they do not focus on dual channels in foreign markets or dual export channels. Therefore, the following question remains unanswered: how do capability factors affect the dual channel choice in foreign markets? To answer this, two elements must be considered. First, the respective effects of EEO and EMO capabilities, and second, the cultural distance between home and host countries. In the next section, this paper considers these two points, develops a conceptual model, and proposes hypotheses.

Figure 1 presents the conceptual model for this study. It shows that the two capability factors, EMO and EEO capabilities, have positive effects on the decision to use dual or independent channels3). Specifically, this study suggests that manufacturers with strong EMO and/or EEO capabilities are likely to choose dual channels. In addition, the conceptual model indicates that cultural distance facilitates the positive effects of these two capability factors. In other words, this study suggests that manufacturers with strong EMO and/or EEO capabilities have a strong tendency to choose dual channels when operating in countries where there is a high level of cultural difference.

Conceptual model.

Manufacturers with strong EMO capabilities, by definition, are good at gathering and processing market information. Such manufacturers attempt to contact their customers directly, gather market information accurately, and respond to market changes promptly. Thus, manufacturers with strong EMO capabilities tend to choose integrated channels rather than independent channels (He et al., 2013). However, manufacturers with weak EMO capabilities are not proficient in gathering and processing market information. Consequently, to complement their weak capabilities in this regard, these manufacturers attempt to indirectly gather and respond to information through capable distributors. Thus, manufacturers with weak EMO capabilities tend to choose independent channels rather than integrated channels (He et al., 2013).

However, manufacturers with strong EMO capabilities do not need to integrate all channels to fully exploit the value afforded by their EMO proficiency (Takata, 2019). This is because information regarding a particular market is applicable to similar market environments. For example, information obtained from customers in a foreign market may be applied to other customers from a different country who are classified within the same target segment. Therefore, it may be effective for manufacturers with high market orientation to partially use integrated channels as an information base. Thus, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Export entrepreneurial orientation capabilityH1: EMO capability is positively related to the likelihood of dual channel choice (as opposed to independent channel choice).

Exporting manufacturers with strong EEO capabilities are good at developing innovative products and discovering new customer needs. To make full use of their capabilities, these manufacturers attempt to directly interact with customers, actively introduce new products/services, and rapidly obtain customer feedback. Thus, manufacturers with strong EEO capabilities tend to choose integrated channels rather than independent channels (Pehrsson, 2015). Meanwhile, exporting manufacturers with weak EEO capabilities are not proficient at generating innovative ideas and discovering new needs. To complement their low-level capabilities in this regard, these manufacturers attempt to introduce new products and services by partnering with good distributors. Thus, exporting manufacturers with weak EEO capabilities tend to choose independent channels rather than integrated channels (Pehrsson, 2015).

However, manufacturers with strong EEO capabilities do not need to integrate all channels to develop and introduce new products and services; partial integration of export channels is sufficient (Mols, 2000). Through a limited number of integrated channels, exporting manufacturers can experiment and test innovative products and services, receive feedback from customers, and consequently improve their products and services. In addition, highlighting sales achievements in integrated channels helps manufacturers persuade distributors to purchase new products. Thus, exporting manufacturers with strong EEO capabilities can fully use their capabilities by using dual channels. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Export market orientation capability and cultural distanceH2: EEO capability is positively related to the likelihood of dual channel choice (as opposed to independent channel choice).

Cultural distance refers to the extent to which norms and values differ between home and host countries (Hofstede, 1980; Kogut & Singh, 1988), with high cultural distance indicating that there are significant differences in regard to norms and values between the manufacturer in the home country and the end customer in the host country. Thus, when seeking to transact with culturally different countries, exporting manufacturers tend to have relatively little knowledge about the needs and preferences of local consumers (Yeoh, 2004). Additionally, they cannot easily predict the behaviors and strategies of rival firms in host countries that have different cultures. When operating in such countries, it is even more critical for exporting manufacturers to choose channel structures that are appropriate to their EMO capabilities. Specifically, manufacturers with strong EMO capabilities have a greater need to choose dual channels, as this will help them to directly gather information and rapidly respond to market changes. In contrast, manufacturers with weak EMO capabilities have a greater need to choose independent channels, as they need to efficiently obtain and respond to market information through independent distributors. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Export entrepreneurial orientation capability and cultural distanceH3: Cultural distance positively moderates the relationship between EMO capability and the likelihood of dual channel choice.

The existence of large cultural distances may make it difficult for exporting manufacturers to understand the needs and preferences of end customers in host countries (Yeoh, 2004). Moreover, local distributors may be cautious in regard to trusting the exporting manufacturer and, thus, may display greater resistance to handling new products and services (Armstrong & Yee, 2001). Entrepreneurial-oriented activities are hampered due to difficulties in understanding customer needs and negotiating with local distributors. Therefore, in such cases, it is essential for manufacturers to choose a channel structure appropriate to their EEO capabilities. Specifically, manufacturers with strong EEO capabilities have a greater need to choose dual channels, as this will allow them to experiment with new products and services and obtain customer feedback, whereas manufacturers with weak EEO capabilities have a greater need to choose independent channels, as this will help them obtain new ideas from independent distributors. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H4: Cultural distance positively moderates the relationship between EEO capability and the likelihood of dual channel choice.

To test the proposed hypotheses, primary survey data were collected because it was difficult to gather secondary data on export channel structures for specific products. The subjects of this survey were 839 business units from chemical, electronics, machine, and metal industries, among others. The present researcher sent a questionnaire, a cover letter, and a postage-paid return envelope to these business units. The cover letter and questionnaire explained the following three points: (1) this survey was being conducted for academic research, (2) the content of the business units’ responses would not be externally disclosed, and (3) a summary report of this survey would be sent to the respondents who provided their name and contact details. A reminder letter was mailed two weeks after the initial survey. A total of 196 business units provided useable responses. The useable response rate of 23.4% was deemed to be satisfactorily high compared to the response rates reported in similar channel studies (Ekeledo & Sivakumar, 2004; Oliveira et al., 2018).

Informant competencyTo collect data concerning the export channels for specific products, business managers with experience of overseas export and distribution were targeted as respondents for this survey (Campbell, 1955). Furthermore, to check informant competency, the questionnaire contained two questions to measure the informants’ level of knowledge and experience regarding export and distribution in foreign countries. For both questions, the semantic differential technique was used, with respondents indicating their level of agreement/disagreement with the items using a seven-level scale. Among the sample, the average value for the level of knowledge was 5.48 (SD = 1.18), and the average value for the level of experience was 6.00 (SD = 0.98).

In addition, the average length of service at the company was 21.6 years (SD = 10.3), the average length of service in the department was 12.2 years (SD = 10.9), and a majority of respondents held senior positions such as managing director, department head, or assistant director. The level of knowledge and experience of these informants was deemed to be sufficiently high compared to prior channel studies (Fürst, Leimbach, & Prigge, 2017; Kabadayi, 2011).

Nonresponse biasTwo methods were used to test for nonresponse bias. First, the method proposed by Armstrong and Overton (1977) was employed. The present research’s early response group comprised respondents who returned their questionnaires before sending the reminder letter—the late response group comprised respondents who returned their questionnaires after the reminder was sent. As late respondents have similar characteristics to non-respondents, a difference should be found between the early response group and the late response group if nonresponse bias is present. The mean values for the dependent, independent, and control variables were compared between these groups. The results of a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) indicated no significant difference (Wilks’ lambda = 0.93, p = 0.84).

Regarding the second method of checking nonresponse bias, of the 839 business units to which the survey was sent, the annual sales of the group of business units that returned the questionnaire was compared with that of the group of business units that did not return the questionnaire. A t-test revealed that no significant difference existed between the two groups. These results suggested that nonresponse bias was not a severe issue in this study.

Common method biasCommon method bias was tested using two methods. First, a Harman’s single-factor test was performed by conducting exploratory factor analysis. The results showed that 10 factors had eigenvalues of 1 or more; these were extracted, and the variance that could be explained by the first factor was as low as 25.2%. Second, the marker variable (MV) technique by Lindell and Whitney (2001) was applied. Specifically, a variable that did not theoretically correlate with the variable used in the analysis was set as an MV, and the partial correlation coefficient controlling the MV was compared with an uncontrolled correlation coefficient. Consequently, minimal variance was found between the coefficients and significance. The above analysis suggests that common method bias was not a significant issue in this study.

MeasuresTo determine the quality of the questionnaire from respondents’ perspectives, preliminary face-to-face interviews were conducted with eight managers who worked for industrial manufacturing firms. The interviews lasted 1–1.5 hours per person. These managers were asked to answer all the survey questions and highlight any questions that they found difficult to answer. Based on their comments, the measurement items were modified and the questionnaire was finalized.

The respondents were asked to concentrate on the export channels for one main product in its main host country when answering the questions. Appendix A shows the measurement items for the dependent, independent, and control variables used in this study, while Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics and coefficients of the correlation matrix.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Dual channel dummy | — | ||||||||||||||||||

| 2. Intelligence generation | −0.07 | — | |||||||||||||||||

| 3. Intelligence dissemination | −0.23* | 0.30* | — | ||||||||||||||||

| 4. Intelligence responsiveness | −0.06 | 0.41* | 0.29* | — | |||||||||||||||

| 5. EMO capability | −0.17* | 0.75* | 0.74* | 0.75* | — | ||||||||||||||

| 6. Innovativeness | 0.01 | 0.37* | 0.22* | 0.38* | 0.42* | — | |||||||||||||

| 7. Risk-taking | 0.03 | 0.20* | 0.10 | 0.21* | 0.23* | 0.30* | — | ||||||||||||

| 8. Proactiveness | −0.07 | 0.49* | 0.35* | 0.45* | 0.57* | 0.56* | 0.33* | — | |||||||||||

| 9. Aggressiveness | 0.07 | 0.24* | 0.07 | 0.35* | 0.29* | 0.25* | 0.23* | 0.46* | — | ||||||||||

| 10. Autonomy | −0.03 | 0.41* | 0.28* | 0.41* | 0.49* | 0.40* | 0.10 | 0.48* | 0.24* | — | |||||||||

| 11. EEO capability | 0.00 | 0.50* | 0.29* | 0.53* | 0.58* | 0.74* | 0.57* | 0.83* | 0.64* | 0.64* | — | ||||||||

| 12. Cultural distance | 0.00 | −0.07 | 0.03 | −0.10 | −0.06 | 0.03 | −0.08 | −0.10 | −0.11 | −0.01 | −0.08 | — | |||||||

| 13. Firm size (log) | −0.01 | 0.32* | 0.17* | 0.14 | 0.28* | 0.18* | 0.17* | 0.16* | 0.05 | 0.24* | 0.23* | −0.08 | — | ||||||

| 14. Years of exporting | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.02 | −0.09 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.10 | −0.02 | — | |||||

| 15. Number of export markets | 0.13 | 0.03 | −0.08 | −0.01 | −0.03 | 0.10 | −0.08 | 0.02 | 0.16* | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.13 | 0.40* | — | ||||

| 16. Asset specificity | −0.08 | 0.18* | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.15* | 0.19* | 0.01 | 0.21* | 0.05 | 0.16* | 0.18* | −0.06 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.00 | — | |||

| 17. Product standardization | 0.04 | −0.04 | −0.09 | 0.05 | −0.04 | −0.17* | −0.04 | −0.19* | −0.02 | 0.06 | −0.11 | 0.00 | −0.04 | 0.12 | 0.02 | −0.13 | — | ||

| 18. Group purchase | 0.10 | 0.06 | −0.22* | 0.12 | −0.03 | 0.08 | 0.08 | −0.03 | 0.05 | −0.03 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.00 | — | |

| 19. Behavior variability | 0.18* | 0.16* | −0.04 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.01 | −0.03 | 0.06 | −0.10 | 0.07 | −0.10 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.05 | 0.19* | — |

| Mean | 0.48 | 4.86 | 4.50 | 4.99 | 4.78 | 4.37 | 2.54 | 4.16 | 3.52 | 4.88 | 3.89 | 2.38 | 11.30 | 22.85 | 19.73 | 5.59 | 4.30 | 3.03 | 4.27 |

| Standard deviation | 0.50 | 1.12 | 1.29 | 1.18 | 0.89 | 1.24 | 1.13 | 1.11 | 1.20 | 1.08 | 0.79 | 0.67 | 1.56 | 14.45 | 23.15 | 0.97 | 1.46 | 1.78 | 1.65 |

| Max | 1.00 | 7.00 | 7.00 | 7.00 | 7.00 | 7.00 | 6.67 | 7.00 | 7.00 | 7.00 | 5.84 | 3.78 | 15.55 | 70.00 | 180.00 | 7.00 | 7.00 | 7.00 | 7.00 |

| Min | 0.00 | 1.50 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.81 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.20 | 0.90 | 8.19 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

Note: *p < 0.05 (two-tailed tests).

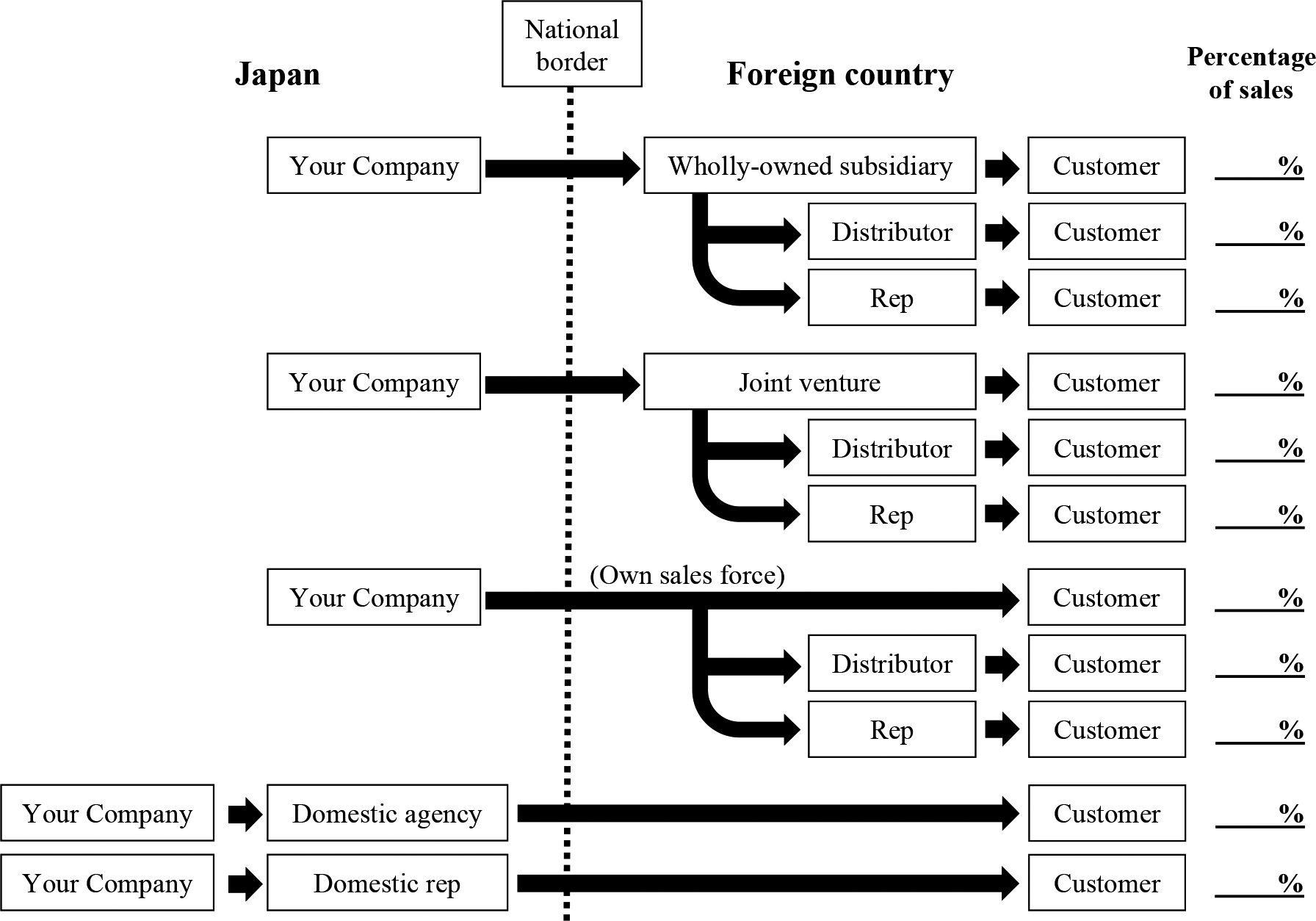

The dependent variable, export channel type, was measured as follows. First, based on existing research (Eyuboglu, Kabadayi, & Buja, 2017; Kabadayi, 2011; Klein et al., 1990; McNaughton, 2002) and the preliminary interviews, a list of 11 channel diagrams was created (see Appendix 1). Of these 11 export channel diagrams, 3 (Your company–Wholly owned subsidiary–Customer, Your company–Joint venture–Customer, and Your Company–Customer) corresponded to integrated channels, while the other 8 corresponded to independent channels. Respondents were presented with this list and asked to state the percentage of sales represented by each export channel in relation to the product in question. Sales percentages via integrated and independent channels were calculated based on these responses. Firms for which the share of sales via integrated channels was greater than 95% were considered to be integrated-channel firms and were coded as 1; meanwhile, firms for which the share of sales from independent channels was 95% or greater were considered to be independent-channel firms and were coded as 2. The remaining firms (i.e., firms for which the shares of sales for integrated and independent channels were 6–94%, respectively) were considered to be dual-channel firms and were coded as 3. Through this approach, of the 196 firms examined, 48 were classified as integrated-channel firms (24.5%), 54 were classified as independent-channel firms (27.6%), and 94 (48.0%) were classified as dual-channel firms.

The concept of EMO capability comprises three dimensions: export intelligence generation, dissemination, and responsiveness. Based on Cadogan, Diamantopoulos, and de Mortanges (1999) and Cadogan, Diamantopoulos, and Siguaw (2002), intelligence generation was measured using four items, while intelligence dissemination and responsiveness were each measured using three items. These items were scored using a seven-point scale. The mean of the items for each of the three dimensions (generation, dissemination, and responsiveness) was calculated. Then the final market orientation indicator was calculated as the average score of the three dimensions. EEO capability is also a multi-dimensional construct, containing five dimensions: export product innovativeness, export risk-taking, export proactiveness, export competitive aggressiveness, and export autonomous behaviors. Innovativeness was measured using five items, risk-taking and aggressiveness were measured using three items, proactiveness was measured using four items, and autonomy was measured using two items. These items were adapted from Boso et al. (2012) and Jambulingam et al. (2005). These items were scored using a seven-point scale. The mean of the items for each of the five dimensions (innovativeness, risk-taking, aggressiveness, proactiveness, and autonomy) was calculated, and then the final entrepreneurial orientation indicator was calculated as the average score of the three dimensions.

Cultural distance is the degree to which norms and values differ between home and host countries. To create a variable for cultural distance, data were first collected for the six cultural dimensions proposed by Hofstede, Hofstede, and Minkov (2010): power distance, collectivism, uncertainty avoidance, masculinity, long-term orientation, and indulgence. Then, scores for these six cultural dimensions for Japan and all host countries served by the present sample were obtained from Hofstede’s website (https://geerthofstede.com). Subsequently, following Bunyaratavej, Hahn, and Doh (2007), the cultural distance variable was calculated as follows:

Several control variables were included in the empirical analysis. Firm size, which was operationalized as annual sales (sourced from secondary information), and exporting experience, which was measured in terms of the number of years the firm had been exporting the product (Aulakh & Kotabe, 1997), and the number of export markets the firm had entered (Cadogan et al., 2002), were controlled. Further, asset specificity was controlled in the model; this construct was measured using three items based on Klein et al. (1990) and McNaughton (2002). To control for channel conflict factors, product standardization, customer behavior variability, and group purchase behavior were included in the analyses. These constructs were measured using a single item based on Sa Vinhas and Anderson (2005). To control for industry-specific effects, industry types were coded as dummy variables and included in the model.

Confirmatory factor analysis was performed on the measurement model, including all the reflective measurement items, using the maximum likelihood method. The results showed a good model fit (χ2 = 618.51 [d.f. = 419, p < 0.01], χ2/d.f. = 1.47, RMSEA = 0.049, CFI = 0.94, IFI = 0.94, TLI = 0.93). Moreover, all average variances extracted (AVEs) were between 0.50 and 0.73, and composite reliabilities (CRs) were in the range of 0.75–0.93. In addition, to check the discriminant validity highest shared variance (HSV) and AVE values were compared. This showed that the AVE values exceeded the HSV values for all measures. These results indicated sufficient convergent and discriminant validity.

To test the hypotheses, multinomial logistic regression analysis was performed; this was because the dependent variable (export channel type) was a categorical variable with three categories. As shown in Table 2, this study analyses the likelihood of dual versus integrated channel choice (Model 1) and dual versus independent channel choice (Model 2), respectively.

| Independent variable | Model 1 | Model 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Dual vs. integrated channels | Dual vs. independent channels | |

| β1: EMO capability | −0.86** (0.34) | −0.68** (0.28) |

| β2: EEO capability | 0.15 (0.35) | 0.66** (0.31) |

| β3: Cultural distance | −0.64* (0.38) | 0.27 (0.32) |

| β4: EMO × CLD | 0.66 (0.56) | 0.79* (0.46) |

| β5: EEO × CLD | 0.62 (0.59) | −0.42 (0.55) |

| β6: Firm size (log) | −0.25* (0.14) | 0.29** (0.14) |

| β7: Years of exporting | 0.02 (0.02) | 0.02 (0.02) |

| β8: Number of export markets | 0.02* (0.01) | 0.00 (0.01) |

| β9: Asset specificity | −0.60** (0.26) | −0.02 (0.20) |

| β10: Product standardization | 0.12 (0.14) | −0.03 (0.13) |

| β11: Group purchase | −0.11 (0.12) | 0.18 (0.12) |

| β12: Behavior variability | 0.30** (0.13) | 0.30** (0.12) |

| β13: Industry dummy (electronics) | −0.83 (1.07) | 0.23 (0.77) |

| β14: Industry dummy (chemical) | −0.63 (1.07) | 0.12 (0.78) |

| β15: Industry dummy (machine) | −0.41 (1.11) | 0.16 (0.78) |

| β0: Constant | 1.66 (1.02) | 0.51 (0.69) |

| Nagelkerke R2 | 0.35 | |

| N | 196 | |

Notes: Unstandardized coefficients are shown (standard errors in parentheses); **p < 0.05, *p < 0.10 (two-tailed tests).

H1, proposing a positive relationship between EMO capability and the dual channel choice, would be supported if EMO capability is related to the choice of dual versus independent channels. With respect to Model 2, the results show that the coefficient of EMO capability is negative and significant (β1 = −0.68, p < 0.05); thus, H1 is not supported. H2, suggesting a positive relationship between EEO capability and the dual channel choice, would be supported if EEO capability is related to the choice of dual versus independent channels. The coefficient of EEO capability is positive and significant (β2 = 0.66, p < 0.05), supporting H2.

Regarding the interaction effect, H3 suggests that cultural distance positively moderates the impact of EMO capability. The coefficient of the interaction term between EMO capability and cultural distance is positive and significant (β4 = 0.79, p < 0.05). To facilitate interpretation of the interaction effect, a binary logistics regression was conducted and a graphical plot was depicted (Dawson, 2014). The results of binary logistic regression are shown in Table 3. It indicates that the coefficient of the interaction term between EMO capability and cultural distance was positive and significant (β4 = 0.80, p < 0.05). Figure 2 illustrates the interaction effects estimated in the binary logistic regression of EMO capability and cultural distance. It indicates that high cultural distance mitigates the negative effect of EMO capability on dual channel choice; thus, H3 is supported. H4, proposing that cultural distance strengthens the positive impact of EEO capability, would be supported if EEO capability and cultural distance interact to positively influence the dual channel choice. The coefficient of the interaction term of EEO capability and cultural distance is not significant (β5 = −0.43, p > 0.10); thus, H4 is not supported.

| Independent variable | Dual vs. independent channels |

|---|---|

| β1: EMO capability | −0.60** (0.28) |

| β2: EEO capability | 0.58* (0.31) |

| β3: Cultural distance | 0.36 (0.35) |

| β4: EMO × CLD | 0.80* (0.49) |

| β5: EEO × CLD | −0.24 (0.62) |

| β6: Firm size (log) | 0.28* (0.14) |

| β7: Years of exporting | 0.03 (0.02) |

| β8: Number of export markets | −0.00 (0.01) |

| β9: Asset specificity | 0.02 (0.21) |

| β10: Product standardization | −0.05 (0.14) |

| β11: Group purchase | 0.19 (0.12) |

| β12: Behavior variability | 0.28** (0.12) |

| β13: Industry dummy (electronics) | 0.52 (0.78) |

| β14: Industry dummy (chemical) | 0.41 (0.79) |

| β15: Industry dummy (machine) | 0.53 (0.80) |

| β0: Constant | 0.14 (1.39) |

| Nagelkerke R2 | 0.19 |

| N | 196 |

Notes: Unstandardized coefficients are shown (standard errors in parentheses); **p < 0.05, *p < 0.10 (two-tailed tests).

Moderating effect of cultural distance.

This study aims to identify capability factors that influence, among exporting manufacturers, the choice to use dual export channels. Although most prior studies assume that exporting firms choose a specific type of export channel, real-world firms often choose dual export channels. In fact, previous survey evidence reveals that several exporting firms choose dual channels in foreign countries (Klein et al., 1990; McNaughton, 2002). Based on these findings, international-marketing researchers emphasize that future studies should focus on dual or multiple export channels (Hoppner & Griffith, 2015; Li, He, & Sousa, 2017). By responding to this call for research, the present study advances understanding of dual channels in foreign markets.

The present study results indicate that exporting manufacturers with strong EEO capabilities tend to choose dual channels rather than independent channels. Entrepreneurial-oriented firms adopt high-risk projects, develop innovative products, and seek new market opportunities. These firms add integrated channels to an independent channel system to test new ideas quickly and obtain customer feedback. This study also finds that exporting firms with strong EMO capabilities are less likely to choose dual channels and more likely to prefer independent channels. Although a dual channel structure facilitates market-oriented activities, the need to control several types of export channels incurs operation costs, and the need to reduce channel conflicts between integrated and independent channels incurs conflict management costs. Exporting manufacturers with strong EMO capabilities choose independent channels because such firms can realize market orientation to some extent without using integrated channels. In contrast, exporting manufacturers with weak EMO capabilities might attempt to develop their capabilities by choosing dual channels.

The results show that the negative effects of EMO capability on the dual channel choice is mitigated by high cultural distance; some exporting manufacturers with strong EMO capabilities choose a dual-channel approach in the context of high cultural distance. High cultural distance indicates the presence of large discrepancies between the firms in the home and host countries in regard to norms, values, and communication styles. In interactions with firms in highly different countries, even manufacturers with strong EMO capabilities can experience barriers to obtaining market information and responding to market changes. A dual channel system enables exporting firms to obtain information from a variety of sources. Thus, when interacting with host countries for which there are marked cultural differences, some exporting manufacturers use dual channel systems and diversify information sources to achieve market orientation.

The findings of this study provide helpful insights for international marketing and global sales managers. Managers should carefully evaluate their firms’ internal capabilities and then develop new export channels or change existing channel structures to suit these capabilities. Specifically, exporting firms with strong EEO capabilities should use, at least to some extent, integrated channels to test and experiment with new products or services. In general, as independent intermediaries are reluctant to invest time and resources in the sales of novel products, depending solely on independent channels may discourage export firms from proactively exploring new markets. Furthermore, exporting firms with strong EMO capabilities should adopt a dual channel strategy when operating in culturally different countries; this strategy diversifies information sources and provides firms with various customer touchpoints. In other words, in interactions with host countries for which there is a high cultural distance from the home country, exporting firms can exploit their strong EMO capabilities by choosing dual channels.

This study has two limitations. First, to test the proposed hypotheses, only cross-sectional data are used. Collection of time-series and/or longitudinal data requires considerable time and money; however, such data may be useful when seeking to determine causal relationships (Rindfleisch, Malter, Ganesan, & Moorman, 2008). Future researchers are encouraged to address this methodological issue by investing time and effort into collecting time-series and/or longitudinal data.

Second, this study uses perceptual data sourced from only one informant from each firm. The decision on export channel selection, which is the unit of analysis in this study, was based on a specific product destined for a specific host country. As no secondary data are available, primary survey data are collected in this study. In fact, the majority of prior research on export channel selection or international marketing channels has adopted a survey methodology (Hoppner & Griffith, 2015; Li et al., 2017). A limitation of this approach is that the respondents may not always have a high ability to answer questions regarding their firms’ strategies. This potential shortcoming can be overcome by contacting multiple respondents and gathering objective evidence.

The findings suggest several directions for future research. Research may be needed to develop better items for measuring EMO capability among Japanese firms. This study uses Japanese translations of established measurements that included many reverse-scored items (Boso et al., 2012; Cadogan et al., 1999; Cadogan et al., 2002; Murray, Gao, Kotabe, & Zhou, 2007). Some studies suggest that Japanese deference norms or “say-yes” tendencies can cause problems regarding the use of reverse-scored items among such populations (e.g., Chung et al., 2006; Wong et al., 2003). By developing a set of EMO capability measures with no reverse-scored items, future research focusing on Japanese firms may obtain more reliable evidence.

Moreover, although this study focuses on two types of capability factors (i.e., export EMO and EEO capabilities), other capability factors may also affect export channel selection. Examples include relational capabilities, such as knowledge-sharing routines and trust (e.g., Dyer and Singh, 1998; Pham et al., 2017; Skarmeas et al., 2016), and other strategic orientation capabilities, such as brand orientation (Laukkanen et al., 2013) and reputation orientation (Goldring, 2015). By examining these effects, future research could advance the understanding of dual and/or multiple export channels.

Furthermore, few studies employ capability theory to investigate dual distribution channels in foreign markets (Ishii, 2020; Takata, 2019). When and what capabilities influence dual channel choice can be further investigated. Also, whether organizational capability influences the selection between dual and integrated channels has not been addressed. In future research, more efforts should be made to address this gap and elaborate the theoretical underpinnings of the capability theory.

The author would like to gratefully appreciate Professor Akinori Ono for his helpful guidance and precious feedback during the development of this paper. The author also thanks Professor Yuncheol Jeong and Professor Hidesuke Takata for their comments on previous versions of the article. The author expresses special thanks to the previous Editor-in-Chief, Professor Tomokazu Kubo, the Area Editor, and the two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments during the entire review process. An earlier version of this paper was presented at the 2020 Global Marketing Conference. This study was financially supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers JP17J03156 and JP20K13619.

| Export intelligence generation (Cadogan et al., 1999, 2002) [CR = 0.87, AVE = 0.62] |

| 1. We periodically review the likely effect of changes in our export environment (e.g., technology and regulation). |

| 2. We generate a lot of information concerning trends (e.g., regulation, technological developments, politics, and economy) in our export markets. |

| 3. We generate a lot of information in order to understand the forces which influence our overseas customers’ need and performance. |

| 4. We constantly monitor our level of commitment and orientation to serving export customer needs. |

| Export intelligence dissemination (Cadogan et al., 1999, 2002) [CR = 0.88, AVE = 0.71] |

| 1. Information about our export competitors activities often reaches relevant personnel too late to be of any use. (R) |

| 2. Important information concerning export market trends (regulatory, technology) is often discarded as it makes its way along the communication chain. (R) |

| 3. Information regarding the way we serve our export customers takes forever to reach relevant personnel. (R) |

| Export intelligence responsiveness (Cadogan et al., 1999, 2002) [CR = 0.83, AVE = 0.62] |

| 1. If a major competitor were to launch an intensive campaign targeted at our foreign customers, we would implement a response immediately. |

| 2. We are quick to respond to significant changes in our competitors’ price structures in foreign markets. |

| 3. We rapidly respond to competitive actions that threaten us in our export markets. |

| Innovativeness (Boso et al., 2012) [CR = 0.93, AVE = 0.72] |

| 1. Our company is known as an innovator among businesses in our industry. |

| 2. We promote new, innovative product/services in our company. |

| 3. Our company provides leadership in developing new products/services. |

| 4. Our company is constantly experimenting with new products/services. |

| 5. We have built a reputation for being the best in our industry to develop new methods and technologies. |

| Risk-taking (Boso et al., 2012; Jambulingam et al., 2005) [CR = 0.89, AVE = 0.73] |

| 1. Top managers of our company, in general, tend to invest in high-risk projects. |

| 2. This company shows a great deal of tolerance for high risk projects. |

| 3. Our business strategy is characterized by a strong tendency to take risks. |

| Proactiveness (Boso et al., 2012; Jambulingam et al., 2005) [CR = 0.82, AVE = 0.53] |

| 1. We seek to exploit anticipated changes in our target market ahead of our rivals. |

| 2. We seize initiatives whenever possible in our target market operations. |

| 3. We consistently try to position ourselves to meet emerging customer demands. |

| 4. Because market conditions are always changing, we continually seek out new opportunities. |

| Competitive aggressiveness (Boso et al., 2012; Jambulingam et al., 2005) [CR = 0.80, AVE = 0.58] |

| 1. We directly challenge our competitors. |

| 2. To achieve competitive goals in the export market, we take hostile means like intensive promotion. |

| 3. We adopt an aggressive way to expand market share in the export market. |

| Autonomy (Boso et al., 2012; Jambulingam et al., 2005) [CR = 0.80, AVE = 0.67] |

| 1. Personnel behave autonomously in our business operations. |

| 2. Personnel are self-directed in pursuit of target market opportunities. |

| Asset specificity (Klein et al., 1990; McNaughton, 2002) [CR = 0.78, AVE = 0.54] |

| 1. To sell the product effectively, a salesperson has to make a lot of efforts to get to know customers in the export market. |

| 2. To be effective, a salesperson needs to learn about the product thoroughly. |

| 3. Special training is needed for a salesperson to sell the product. |

| Product standardization (Sa Vinhas & Anderson, 2005) [CR = 0.75, AVE = 0.62] |

| 1. We think that our customers perceive the characteristics of the products as being similar with competitors’ products. |

| 2. We think that our customers perceive that the products are very typical of the categories. |

| Group purchase (Sa Vinhas & Anderson, 2005) [single item] |

| Group purchases are sometimes made by targeted customers. |

| Behavior variability (Sa Vinhas & Anderson, 2005) [single item] |

| There are many customers who purchase very different quantities of product on different purchasing occasions. |

Notes: All items were measured using seven-point scales anchored by 1 = ‘strongly disagree’ and 7 = ‘strongly agree’, unless otherwise indicated; CR = composite reliability; AVE = average variance extracted.

The list of export channel types