2022 年 5 巻 2 号 p. 37-55

2022 年 5 巻 2 号 p. 37-55

Despite the growing academic attention to consumer affinity, the study of its antecedents had been relatively ignored. The current study focuses on the effect of service recovery on consumer affinity in intercultural service encounters (ICSEs) involving customers and employees from different cultures. The current study has three purposes: (1) determine whether good service recovery improves consumer affinity and, in turn, revisit intention in ICSEs; (2) examine whether this effect is also confirmed in a relative high animosity country; and (3) examine the psychological process by which service recovery enhances consumer affinity. We conducted a series of scenario-based experiments to examine our hypotheses. The results revealed that good service recovery led to greater intention to revisit the country via consumer affinity as opposed to bad service recovery. However, the effect of service recovery disappeared or attenuated in a high animosity country. Further, two types of service recovery (i.e. process and outcome) influenced consumer affinity via both warmth and competence. We discussed theoretical implications, practical contributions, and future research directions based on the empirical results.

In recent years, an increasing number of studies have focused on consumers’ positive beliefs or attitudes toward foreign countries (Bartsch, Riefler, & Diamantopoulos, 2016). Among other types of positive disposition toward foreign countries, this study focuses on the concept of consumer affinity (Jaffe & Nebenzahl, 2006; Nes, Yelkur, & Silkoset, 2014; Oberecker, Riefler, & Diamantopoulos, 2008; Wongtada, Rice, & Bandyopadhyay, 2012). Consumer affinity refers to “country-specific favorable feelings toward particular foreign countries” (Oberecker & Diamantopoulos, 2011, p. 45).

Despite the growing academic attention to consumer affinity, the study of its antecedents has been relatively ignored. A few studies have reported that personal experiences (e.g., stay abroad, travel contact with friends) foster consumer affinity (Bernard & Zarrouk-Karoui, 2014; Oberecker et al., 2011). Although these studies have shown interesting results, the nature of such research was still exploratory (i.e., consumer interview and survey) without adequate theoretical foundation. In addition, most of the antecedents examined are difficult for marketers to manage, creating challenges in deploying them in business practice. Therefore, questions remain regarding how marketers can increase consumer affinity and what mechanisms are involved in reinforcing it.

The current study focuses on the effect of service recovery on consumer affinity in the international tourism context in which a customer traveling abroad comes into contact with a local service provider. Such service encounters involving “customers and service employees from different cultures” (Sharma, Tam, & Kim, 2009, p. 227) are called intercultural service encounters (ICSEs)1). “A typical inter-cultural service encounter is given if a foreign customer (of culture B) consumes a service of a domestic provider (of culture A)” (Stauss & Mang, 1999, p. 331). It is thus reasonable to assume that service recovery performed by this service employee will influence consumer affinity in ICSEs. Indeed, foreign tourists may perceive service recovery in ICSEs as a symbolic event that indicates the nature of that country or region. There is no research that directly supports this argument, but there is confirmed anecdotal evidence. For example, in 2017, a Japanese railroad company apologized for departing 20 seconds earlier than scheduled. The company apology announcement was received with surprise abroad as a unique indication of Japanese punctuality (e.g., BBC, 2017). As we discuss in detail later, the above contention that service recovery performed by service employee transforms consumer affinity more in favor regarding the country is justified by emotional attachment theory (Bowlby, 1979). By examining whether appropriate service recovery does or does not improve consumer affinity, our research contributes to international and services marketing study.

Having international tourism research examine the role of service recovery and consumer affinity is also beneficial. International tourism research has focused on increasing the consumer intention to revisit tourism destinations (Afshardoost & Eshaghi, 2020), as ensuring repeat tourist customers is more cost effective than attracting new tourists (Um, Chon, & Ro, 2006). While the prior research has revealed multiple predictors of revisit intention (Afshardoost & Eshaghi, 2020; Josiassen, Assaf, Woo, & Koch, 2016), to the best of our knowledge, no studies have yet examined the role of service recovery and consumer affinity. These concepts should be considered for the desired goal of increasing revisit intention. Because it is assumed that the greater the perceived cultural distance, the greater will be the differences between customers and service providers regarding norms and values, an increase in service failures will likely appear in ICSEs (Sharma et al., 2009; Stauss & Mang, 1999). Indeed, the Japan Finance Corporation published a booklet for the hotel industry describing how to prevent service failures unique to ICSEs (Japan Finance Corporation, 2019). The National Consumer Affairs Center of Japan also launched a consumer hotline for foreign tourists to be able to support their consumption problems while visiting Japan and providing seven languages for clearer communication (National Consumer Affairs Center of Japan, 2018). In other words, stakeholders in the hospitality industry now emphasize the importance of service failure and recovery in ICSEs. In light of this background, it is worthwhile to explore the relationship between revisit intention and service recovery in the international tourism context.

Taken all together and drawing on emotional attachment theory (Bowlby, 1979), we assert that the experience of good service recovery while traveling (i.e., ICSEs) enhances consumer affinity to that specific country, thereby leading to a greater intention to revisit it. To understand the effect of service recovery more clearly, this study also examines whether this effect is confirmed for a country with relative high animosity. The current study also investigates the underlying mechanism that explains just how good recovery increases consumer affinity by using the fundamental concepts for forming human impressions, namely, warmth and competence (Güntürkün, Haumann, & Mikolon, 2020).

It should also be noted that the current study views consumer affinity as a more suitable mediating factor between service recovery and revisit intention than does customer satisfaction. While it is service employees who perform any service recovery, consumer affinity is an evaluation of the country where these employees work. Although we can explain the intention to revisit a service provider based on customer satisfaction, it is difficult to account fully for a mechanism the spillover effects (i.e., evaluation of the country to which the employees belong) using this same concept. Customer satisfaction refers to post-consumption customer evaluations of the product or service in question (Homburg, Koschate, & Hoyer, 2005; Oliver, 2010); that is, a useful predictor for the reuse of those products or services. However, that is not a persuasive explanation to use to capture the spillover effects that we are trying to examine here.

A number of international marketing studies have examined consumer biases toward foreign countries. One of the seminal works on this theme was Shimp and Sharma (1987), focusing on consumer ethnocentrism. This concept is defined as the beliefs held by domestic consumers about “the appropriateness, indeed morality, of purchasing foreign made products” (p. 280). A number of studies on consumer ethnocentrism have followed since then (Shankarmahesh, 2006). Studies along this line developed a relevant but different concept: consumer animosity (Klein, Ettenson, & Morris, 1998). Although consumer ethnocentrism involves negative beliefs about foreign products or services in general, consumer animosity is a country-specific hostile feeling (Klein et al., 1998). Prior studies have revealed that the higher the consumer animosity, the more reluctant consumers are to buy products from the focal country (Klein et al., 1998; Leong et al., 2008).

Most international marketing studies have focused on negative consumer beliefs or attitudes toward foreign countries. However, recent studies have sought to elucidate the effects of positive cognitive biases or feelings toward foreign countries (Terasaki, Ishii, & Isoda, 2021). Among various types of positive dispositions toward a foreign country (Bartsch et al., 2016), we focus our interest on consumer affinity. Oberecker et al. (2008) defined consumer affinity as “a feeling of liking, sympathy, and even attachment toward a specific foreign country that has become an in-group as a result of the consumer’s direct personal experience and/or normative exposure and that positively affects the consumers’ decision making associated with products and services originating from the affinity country” (p. 26). As implied in this definition, consumer affinity was conceptualized based on social identity theory (Tajfel, 1982). Oberecker et al. (2008) “found the theoretical roots of consumer affinity in the distinction between in- and out-groups and the potential inclusion of out-groups to people’s in-groups” (p. 49). Oberecker and Diamantopoulos (2011) subsequently developed a scale to measure consumer affinity.

Consumer affinity and animosity seem bi-polar on the same scale. However, a distinguishing factor of consumer affinity is that it is also aroused by micro factors (i.e., personal experiences) such as travel, whereas consumer animosity mainly stems from macro factors like economic and political conflicts (Oberecker & Diamantopoulos, 2011; Wongtada et al., 2012). Asseraf and Shoham (2017) asserted that consumer affinity and animosity can coexist simultaneously and proposed the “Affinity-Animosity-Collective Memory Matrix” (p. 382) to explain a mixed emotion (i.e., affinity and animosity). According to their framework, for instance, Japanese people may develop negative feelings toward South Korea because of political conflicts surrounding the issue of former forced laborers. Meanwhile, they can have positive feelings toward South Korea based on their attractive culture, such as K-pop, fashion, and makeup.

It is worth noting that major dispositions toward foreign countries, including ethnocentrism or animosity, are formed through socio-psychographic and demographic factors (Sharma, Shimp, & Shin, 1994) that are difficult to control by marketing managers, whereas consumer affinity is malleable and can be altered. This nature of consumer affinity strongly benefits service practitioners. Although consumer affinity is a relatively new concept (Jaffe & Nebenzahl, 2006), several studies have reported that consumer affinity has a positive impact on marketing outcomes, such as willingness to buy, intention to visit, and invest (Asseraf & Shoham, 2017; Nes et al., 2014; Oberecker & Diamantopoulos, 2011; Wongtada et al., 2012). Asseraf and Shoham (2017) stated that consumer affinity “provides a potential tool for policy makers and marketing managers to overcome negative consumer attitudes toward a specific COO and reposition the country image/brand in the desired direction” (p. 376). Indeed, the effect of consumer affinity on willingness to buy outweighed consumer ethnocentrism (Oberecker & Diamantopoulos, 2011). Although a “history of conflicts and tensions between countries or cultures cannot be changed” (Asseraf & Shoham, 2017, p. 378), marketing managers can alter consumer affinity through good service practice.

Despite the usefulness of the concept, prior studies have scarcely examined the factors that engender consumer affinity (except for Asseraf & Shoham, 2017; Bernard & Zarrouk-Karoui, 2014; Oberecker et al., 2011). One of the few studies performed is a work of qualitative research based on consumer interviews (Oberecker et al., 2008). This seminal work about consumer affinity reported that personal experiences (e.g., stay abroad, travel contact with friends) could foster consumer affinity. They explain that consumer affinity engenders feelings of inclusion of a focal foreign country into one’s in-group through personal experiences based on social identity theory. However, there is still opportunity for further study of the process by which a focal foreign country that was in the out-group for consumers becomes recognized as belonging to the in-group.

In addition, Asseraf and Shoham (2017) found that cultural similarity and collective memory predict consumer affinity based on qualitative research. Furthermore, Bernard and Zarrouk-Karoui (2014) explored the possible sources of consumer affinity using a survey. A multiple regression analysis revealed that consumer affinity is moderately correlated with personal experiences (e.g., having friends, visiting the country often), beauty of nature, and culture. Although these studies showed interesting results, the nature of research was exploratory (i.e., consumer interview and survey) without an adequate theoretical foundation. Furthermore, the antecedents examined by Bernard and Zarrouk-Karoui (2014) are difficult for marketers to control (e.g., beauty of nature, culture). In addition, Bernard and Zarrouk-Karoui (2014) measured personal experiences using three items: “I know a lot of people living there”, “I have friends living there”, and “I have visited this country often”. These items also make it difficult to answer the question of which experiences with the country visited are related to consumer affinity. Therefore, several questions remain as to how marketers can increase consumer affinity and what mechanisms are involved in reinforcing it.

Next, we review the service recovery literature and hypothesize the relationship between service recovery and consumer affinity. As previously stated, this current study focuses on service recovery among various potential predictors, mainly because service recovery is a signature event for that country or region. In addition, the memory vividness perspective also justifies the selected reason for focusing on service recovery. According to the halo effect (Thorndike, 1920), a significant experience such as service failure and recovery could influence the overall evaluation of the country by a consumer. This notion is in line with the study on memorable tourism experiences (Park & Santos, 2017). Park and Santos (2017) explored the constitution of memorable tourism, and the results revealed that international tourists tend to remember and reconstruct experiences characterized by unexpectedness, fortuitousness, and adverseness after travel, while also including “flight delays or having something stolen” (p. 22). These memorable tourism experiences clearly influence customer satisfaction and behavioral intention (Coudounaris & Sthapit, 2017; Oh, Fiore, & Jeoung, 2007). If the service provider does not offer effective service recovery, then consumers will remember their negative emotions, which thus have a negative impact on their consumer affinity and revisit intention and vice versa.

Effect of Service Recovery in Intercultural ContextService recovery is defined as “the actions taken by an organization in response to a service failure to improve the situation for the customer” (Zeithaml, Bitner, & Gremler, 2017, p. 179), as service failures are inevitable for all service providers, no matter how careful they are. Therefore, it is quite important to recover customer satisfaction by implementing good service recovery. Prior literature has revealed that good service recovery increases trust and commitment (Tax, Brown, & Chandrashekaran, 1998), corporate image (Mostafa, Lages, Shabbir, & Thwaites, 2015), customer profitability (Cambra-Fierro, Melero, & Sese, 2015), as well as customer satisfaction, loyalty, and word of mouth (Gelbrich & Roschk, 2011).

Although various benefits of service recovery have been confirmed, few studies have shed light on the effect of service recovery on consumer affinity during ICSEs (except for Terasaki & Taketani, 2021). Terasaki and Taketani (2021) revealed that high consumer affinity can be elicited more effectively through good service recovery rather than bad service recovery. However, if people originally have high animosity toward that country, the effect disappears. Although such findings are interesting, this study is exploratory in nature and lacks a theoretical background; the reasons good service recovery can increase consumer affinity were not fully explored.

Within this study, we introduce emotional attachment theory (Bowlby, 1979) to justify the notion that good service recovery increases consumer affinity. This work also contributes to prior research, offering complementary explanation for the process of inclusion of the focal foreign country into the in-group. Emotional attachment theory explains that “infants are born with a repertoire of behaviors (attachment behaviors) aimed at seeking and maintaining proximity to supportive others (attachment figures)” (Mikulincer, Shaver, & Pereg, 2003, p. 78). These behaviors, called the attachment behavior system, “emerged over the course of evolution, because it increased the likelihood of survival of human infants” (Mikulincer et al., 2003, p. 78). Attachment theory originally emerged as a theory explaining the mechanisms by which infants increase their probability of survival, but today its application has been extended to adults (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007). The basic tenet is that, even those who are fully matured, especially when they are exposed to threat, pain, loneliness, and demoralization, they seek proximity to attachment figures (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007). According to Shaver and Mikulincer (2002), when people perceive a potential or actual threat, then the attachment behavior system activates, seeking external (i.e., actual supportive others, Mikulincer et al., 2003) or internalized attachment figures. If the attachment figures are available, they perceive a sense of attachment security, and they “relax, enjoy, and appreciate the feeling of being loved and comforted, and confidently return to other activities” (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007, pp. 141–142).

Emotional attachment theory has also been applied to marketing studies (Malär, Krohmer, Hoyer, & Nyffenegger, 2011) and organizational behavior studies (Yip, Ehrhardt, Black, & Walker, 2018). While most of these studies have applied emotional attachment theory to close relationships, Lee and Thompson (2011) applied this theory to non-close relationships in a work context (i.e., principal-agent relationship in negotiation task). Lee and Thompson (2011) primed the attachment patterns between principal-agent by scenario stimuli, confirming that participants in the attachment secured condition achieve a favorable negotiation outcome for principal rather than non-secured conditions (i.e., anxious attachment, avoidant attachment). Furthermore, people can form attachments to non-human objects as well. Guo, Tu, and Cheng (2018, p. 690) stated that, “according to emotional attachment theory (Bowlby, 1979), individuals may be emotionally attached not only to other people but also to a specific referent such as a place or a country (Bernard & Zarrouk-Karoui, 2014).” They continued that, “in the case of consumer affinity, if consumers have personal contact with the other country––for example, if they have studied or traveled there (Nes et al., 2014)––this fact would yield an emotional attachment to this country, and thus result in cognitive and behavioral action toward it.”

The process of consumer affinity to a foreign country can be mediated by their affinity to a person in that country. “Consumer experience with a country as a whole is more symbolic and hard to pinpoint,” whereas “feelings toward persons may be more tangible, since one can interact directly with other human beings” (Wongtada et al., 2012, p. 162). The original consumer affinity scale developed by Wongtada et al. (2012) comprised three dimensions. One of the subconstructs is people affinity measured by the items, “Americans are friendly” and “Americans are likable”. In other words, consumer affinity for people in a foreign country can translate into affinity for the focal foreign country.

Applying above discussion to our study context, customers who encounter service failures in a foreign country (i.e. ICSEs) seek support for others to mitigate their insecurity. If they can be offered excellent service recovery from local service providers, customers feel secure, thereby shaping affective bond with them. The attachment to a service provider can also become consumer affinity toward that foreign country. Furthermore, once a consumer affinity for a foreign country has been established, consumers try to maintain it (Mikulincer et al., 2003). For example, Oberecker et al. (2008) found that increased willingness to purchase foreign products “is largely derived from a desire to consume products as a means to stay connected to the affinity country” (p. 50). Although Oberecker et al. (2008) did not mentioned emotional attachment theory, this notion is in line with that theory. Also, consumer affinity not only increases consumers’ intention to purchase focal foreign products, but also increases their intention to invest in and visit the country (Oberecker & Diamantopoulos, 2011). Taken together, we hypothesize that good service recovery improves consumer affinity towards the country, therefore increasing tourists’ revisit intention toward the country.

Service Recovery Paradox for Consumer AffinityAccording to the service recovery literature, good service recovery can result in better customer satisfaction than if there had been no service failure in the first place. This phenomenon refers to the service recovery paradox (De Matos, Henrique, & Rossi, 2007). Prior research explained the mechanism based on script theory (Magnini, Ford, Markowski, & Honeycutt Jr., 2007).

Script theory contends that there is a common sequence of acts in service encounters in which customers and employees “share similar beliefs regarding their roles and the expected sequences of events and behaviors (Bitner et al., 1994)” (Magnini et al., 2007, p. 214). Therefore, “service failures heighten the sensitivity and awareness of the customer due to deviation from an anticipated transactional script” (Magnini et al., 2007, p. 214). Because of the heightened attention to the service failure, “service recovery efforts are usually very salient in the consumer’s mind” (Magnini et al., 2007, p. 214). Therefore, researchers contend that satisfaction with service recovery is more important than initial satisfaction in forming overall satisfaction. Indeed, using the critical incident technique, Bitner, Booms, and Tetreault (1990) reported that if customers received excellent service recovery, even the service failures can be remembered as highly satisfactory service encounters.

Although consumer affinity and customer satisfaction differ in terms of object of evaluation (country vs. products/services used), consumer affinity is similar to customer satisfaction regarding emotional responses to an object, so a service recovery paradox can also occur when consumer affinity is the dependent variable. Therefore, we also compare the difference in consumer affinity between performing a good service recovery condition and a no service failure condition (i.e., providing a good service condition). Hence, the following hypotheses are offered:

H1: Good service recovery increases consumer affinity more than (a) bad service recovery and (b) no service failure condition (good service condition).

H2: Good service recovery improves intention to revisit the destination country via consumer affinity.

Jaffe and Nebenzahl (2006) proposed the combined halo and summary model. This model states that, although consumers’ decision-making is influenced by their original country image, their country image is updated through the experience of using the purchased product. The updated country image will then influence those consumers’ next purchase decision. Based on the model, we can hypothesize about the moderating effect of consumer animosity on the relationship between service recovery and consumer affinity. The combined halo and summary model implies that if consumers experience a good service recovery, their affinity toward the country will be positively affected. However, the degree of consumer affinity depends on their animosity. If consumers have higher animosity, the lift effect of excellent service recovery is limited.

Terasaki and Taketani (2021) revealed that, if people have high animosity toward a country, the good service recovery effect disappears. Although the antecedent variables of consumer animosity and affinity are not identical (Oberecker & Diamantopoulos, 2011) and the valence is contrary, these concepts share similarities in terms of attitude toward a specific country. Therefore, we predict that the effect of service recovery stated in H1 and H2 only appears if people originally have relatively low animosity toward that nation, whereas the effect disappears or attenuates in the case of high animosity toward a nation. Formally stated:

Psychological Process of Improving Consumer AffinityH3: The good service recovery effect on consumer affinity and revisit intention only appears if people originally have relatively low animosity, whereas if people have high animosity to the country, the effect of service recovery disappears or attenuates.

While previous research suggests that good service recovery improves consumer affinity, what is the psychological process behind it? By clarifying this regard, we can gain a better understanding of more effective ways to restore consumer affinity. To answer this question, we again draw attention to the process of generating consumer affinity for a foreign country. As emotional attachment theory suggests, consumers have affinity not only for people, but also for countries (Guo et al., 2018). The starting point is that consumers seek others’ support to mitigate their insecurity in a service failure situation (Shaver & Mikulincer, 2002). As previously discussed, consumer affinity for a foreign country could be based on the consumer affinity for people in that country (Wongtada et al., 2012). This is because it is easier for consumers to have a more concrete impression of a person with whom they can directly interact rather than a country that is an abstract entity. By identifying the impressions that consumers have of service providers, we can elucidate the mechanisms that generate consumer affinity toward people in a foreign country. Thus, we can present ways to effectively increase consumer affinity for a country.

Here, we introduce the stereotype content model (Fiske, Cuddy, Glick, & Xu, 2002) to examine the process of impression formation about service providers in detail. According to this theory, when we encounter other people, we are inclined to judge them based on two fundamental dimensions: warmth and competence. Warmth is related to others’ intentions toward an individual. A person with “positive, cooperative intentions appears warm,” whereas a person with “negative, competitive, or exploitative intentions seems cold” (Kervyn, Fiske, & Malone, 2012, p. 167). Warmth is measured by items such as helpfulness, sincerity, and friendliness. Competence is related to the other’s ability to perform intentions. “Another able to implement intentions is perceived as competent,” whereas “another perceived as unable to do so is perceived as incompetent” (Kervyn et al., 2012, p. 167). Competence is measured by items such as efficiency, intelligence, and skillfulness.

The stereotype content model has been applied to the services marketing research. For example, Ang, Liou, and Wei (2018) revealed that consumer participation in the service delivery process increases the perceived warmth and competence of employees in ICSEs. Because customers involved in the service delivery process can obtain actual information regarding service employees (e.g., personal characteristics) through communication with them, results show decreasing dependence on negative stereotype judgment. In addition, Habel, Alavi, and Pick (2017) showed that employees’ behavior (i.e., enforcing service rules to customers) influences customers’ loyalty to firms via perceived employee competence. Furthermore, Choi, Mattila, and Bolton (2021) revealed that service recovery provided by a humanoid robot improves consumer satisfaction via warmth perception.

As these studies indicate that customers judge the competence and warmth of service providers, such judgments affect the marketing outcome variables. This view is also consistent with the combined halo and summary model (Jaffe & Nebenzahl, 2006), which argues that product purchases and usage experiences transform country image by modifying the brand image. Based on the discussion thus far, we apply the stereotype content model to explain why good service recovery affects consumer affinity.

In service recovery situations, consumers judge the warmth and competence of service providers based on their restore actions. There are two types of service correction behaviors: process recovery and outcome recovery (McCollough, Berry, & Yadav, 2000; Zhu, Sivakumar, & Parasuraman, 2004). Consumers evaluate process recovery in terms of whether service providers are “empathetic, apologetic, and responsive” (McCollough et al., 2000, p. 125), whereas consumers evaluate outcome recovery in terms of whether monetary compensation (e.g., discount, voucher, reperformed service) is fair. Prior research has shown that, when consumers experience process failure (e.g., inattentive employee behavior), they prefer process recovery to outcome recovery, whereas consumers prefer outcome recovery to process recovery in cases of outcome failure (e.g., failed core service; Choi et al., 2021; Roschk & Gelbrich, 2014).

Choi et al. (2021) asserted that process recovery is related to consumers’ warmth perceptions, because it conveys sincerity. Their study confirmed the mediating effect of warmth between an apology and consumer satisfaction in the case of process failure. On the other hand, to the best of our knowledge, there is no direct research on the relationship between outcome recovery and warmth/competence, but we predict that outcome recovery is related to consumers’ competence perceptions. As compensation is a costly service recovery method (Cambra-Fierro et al., 2015), the decision to compensate or not is generally made by managers, not frontline employees. Thus, the implementation of compensation could impress customers with the association of being an empowered and competent employee. Based on the discussion herein, we introduce two hypotheses:

H4a: The effect of process recovery improves consumer affinity via warmth rather than competence.

H4b: The effect of outcome recovery improves consumer affinity via competence rather than warmth.

Recently, Güntürkün et al. (2020) identified the interesting correspondence between warmth/competence and marketing outcomes. According to their study, the relative strength of the influence of competence and warmth on the marketing outcome variables vary depending on the nature of the outcome variable; specifically, if outcome variables capture relational aspects (e.g., customer–company identification, customer–company attachment), warmth is more influential than competence, whereas if outcome variables capture transactional aspects (e.g., customer share of wallet, customer willingness to purchase), competence is more influential than warmth. As consumer affinity denotes an emotional sympathy or attachment to a country, it could more dominantly capture a relational aspect. Therefore, it is reasonable to think that warmth has a stronger correlation with consumer affinity than competence.

H5: Warmth more strongly correlates with consumer affinity than competence.

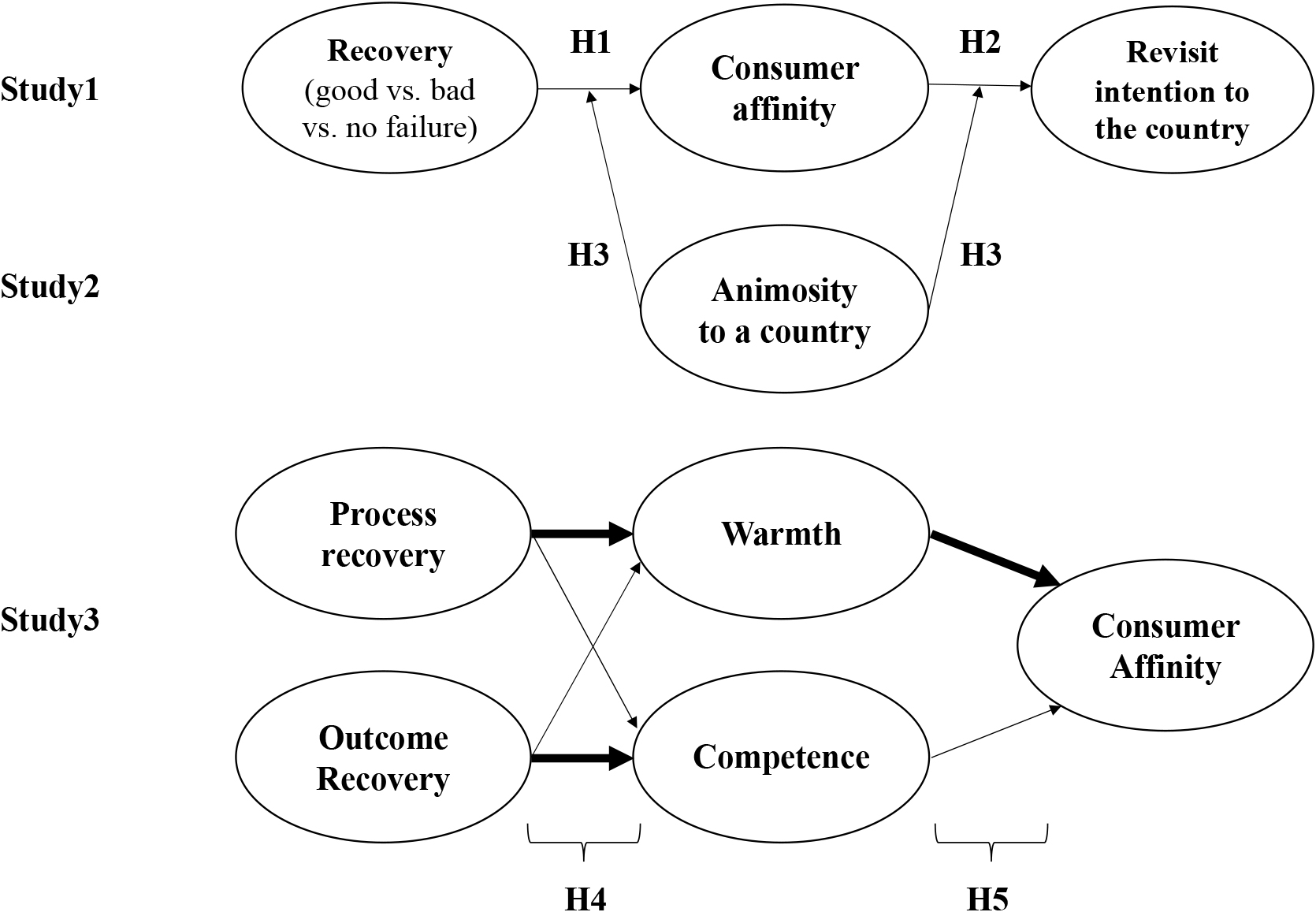

Study 1 aims to answer the following fundamental question: Does good service recovery improve consumer affinity in ICSEs? Using scenario-based experiments, we establish a basic service recovery effect that good service recovery improves consumer affinity in Germany2) (low animosity country for Japanese, Study 1a and Study 1b). Study 2 aims to answer the following question: Is good service recovery effective in countries with high animosity? We use the South Korea scenario (high animosity country for Japanese, Study 2a and Study 2b). We examine the mediation effect of consumer affinity on intention to revisit the country (Study 1 and 2). Finally, we explore the following question: What is the psychological mechanism by which service recovery enhances consumer affinity? We show the underlying mechanism of service recovery’s effect on consumer affinity based on a scenario experiment (Study 3). In sum, Study 1 and Study 2 examine H1 through H3 while Study 3 examines H4ab and H5. Hypotheses 1 through 5 are illustrated in Figure 1.

Conceptual model and proposed hypotheses.

A scenario-based experiment was conducted to examine the effect of service recovery on consumer affinity. This study adopted a single-factor (good recovery vs. bad recovery vs. no service failure [good service]) between-subject experimental design. The study utilized three scenarios for the experiments. The good and bad recovery scenarios made participants imagine an unreasonable service delivery delay that occurred in a restaurant in Germany (adapted from Roschk & Gelbrich, 2017). This trouble made it difficult to be able to meet up with a local friend in time. For those participants in the good recovery scenario group, the restaurant manager provided full compensation for their lunch and offered a sincere apology. The manager also offered to arrange a taxi from the restaurant. For the bad recovery scenario group, the restaurant manager did not provide any compensation and offered an excuse with an unpleasant attitude. In the no service failure scenario, participants experienced good service in the restaurant without any service failures and recoveries.

An online experiment was conducted by a professional research firm that recruited 480 respondents in Japan in September 2020. After reading the scenario, participants answered three plain questions to check the manipulation by scenario (“Q1. In the scenario, it took more than 40 minutes for the dish to be served”; “Q2. In the scenario, the meal cost was free”; “Q3. In the scenario, the restaurant manager offered a sincere apology”). Chi-square analysis revealed the differences in the three questions, respectively (Q1: χ2(2) = 191.50, p < .00, Cramer’s V = .63; Q2: χ2(2) = 279.66, p < .00, Cramer’s V = .76; Q3: χ2(2) = 219.30, p < .00, Cramer’s V = .68). Follow-up examination of the adjusted standardized residuals (ASR) for Q1 revealed that the percentage of respondents who reported waiting 40 minutes was significantly higher for those in the good service recovery condition (ASRQ1 = 6.72) and in the bad service recovery condition (ASRQ1 = 7.12), while it was significantly lower for those in the no service failure condition (ASRQ1 = −13.84). The same procedure was used to analyze Q2 and Q3, and the results showed that a significantly higher percentage of respondents in the good service recovery condition reported receiving free meals (ASRQ2 = 16.72) and a sincere apology (ASRQ3 = 14.50), while these percentages were significantly lower in the bad service recovery condition (ASRQ2 = −8.77; ASRQ3 = −9.88) and no service failure condition (ASRQ2 = −7.95; ASRQ3 = −4.61). Therefore, we found that the participants were properly manipulated by the scenario we created.

To ensure manipulation validation and attention check (Alvarez, Atkeson, Levin, & Li, 2019), this study eliminated inattentive respondents who answered three plain yes/no questions incorrectly at least once. After these respondents were eliminated, the final sample size was 341 (female = 182, male = 159, mean age = 44.63 [SD = 14.16]).

We measured consumer affinity and intention to revisit Germany as dependent variables (see Appendix). These measures were translated into Japanese through consultation between two marketing scholars to ensure the equivalence and clarity of meaning. Each item was measured on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from (1) strongly disagree to (7) strongly agree. A travel experience to Germany in private life (dummy coded variable, 1: Yes, 0: No) and perceived service failure severity were also measured as control variables.

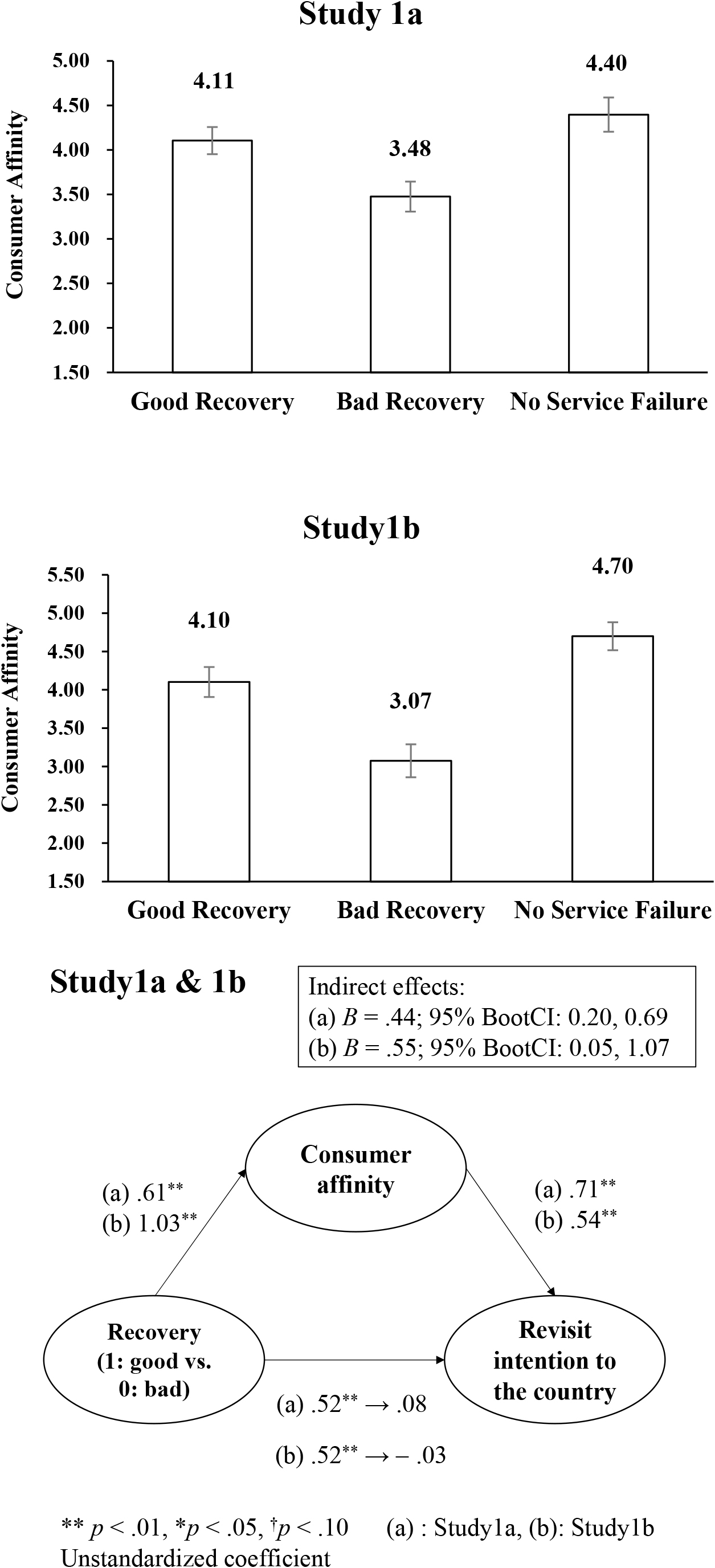

ResultsTo test H1, we conducted a one-way ANCOVA with consumer affinity as the dependent variable. The ANCOVA model comprised 3 predictors: two class variables (the service recovery condition and the travel experience to Germany in private life) and one covariate (perceived service failure severity). The overall model was significant (F(4,336) = 10.85, p < .00, ηρ2 = .11). The result revealed that the main effect of the service recovery condition (F(2,336) = 9.94, p < .00, ηρ2 = .06) and travel experience to Germany (F(1,336) = 17.22, p < .00, ηρ2 = .05) were significant, whereas perceived service failure severity was not significant (F(1,336) = .10, p = .75, ηρ2 = .00). Figure 2 shows the results of planned contrasts3). Consumer affinity was higher in the good recovery group than in the bad recovery group (Mgood recovery = 4.11 vs. Mbad recovery = 3.48, p < .01, d = .47), whereas there was no significant difference between the good recovery group and the no service failure group (Mgood recovery = 4.11 vs. Mno service failure = 4.40, p = .47, d = −.22). Therefore, H1 was partially supported.

Results of Study 1.

To examine the mediating effect of consumer affinity (H2), we regressed revisit intention on service recovery (dummy coded variable, 1: good service recovery, 0: bad service recovery) using good recovery and bad recovery groups (n = 241) with two control variables (i.e., travel experience to Germany; service failure severity). The results indicated that the effect of service recovery on revisit intention was significant (B = .52; p < .01). Then we performed a mediation analysis with the same control variables using PROCESS (model 4; Hayes, 2018) with 10,000 bootstrapping iterations4) (see Figure 2). The results revealed that the direct effect of service recovery on revisit intention was not significant (B = .08; p = .60; 95%CI: −0.22, 0.39), whereas the indirect effect of service recovery on revisit intention did not include zero (B = .44; 95% BootCI: 0.20, 0.69). This indicated that good service recovery improves intention to revisit via consumer affinity. Therefore, H2 was supported.

Study 1b MethodsWe examined H1 and H2 using additional data (N = 105, February 2020). This study adopted a single-factor (good recovery vs. bad recovery vs. no service failure [good service]) within-subject experimental design. Utilizing the within-subject data enabled us to minimize individual differences. Scenarios and scales were identical to those in Study 1a, however we did not ask control variables. After eliminating inattentive samples using the same method as in Study 1a, the final usable sample size was 46 (female = 25, male = 21, mean age = 45.02 [SD = 12.61])5).

ResultsBecause the sample size was relatively small, we conducted a nonparametric test6). The Friedman test for three pairs yielded a significant difference (χ2(2) = 48.81, p <.00). Wilcoxon tests were used to follow up on this finding. The results showed that good service recovery generates higher consumer affinity than bad service recovery (z = 4.79, p < .00, r = .56). Contrary to Study 1a, the consumer affinity score was higher in the no service failure condition than in the good service recovery condition (z = −4.49, p < .00, r = −.52), Therefore, H1 was partially supported again7).

To test H2, a mediation analysis was conducted using the MEMORE Macro (model 1; Montoya & Hayes, 2017) with the good and bad service recovery sample (see Figure 2). The results revealed that the indirect effect of service recovery on revisit intention did not include zero (B = .55; 95% BootCI: 0.05, 1.07), whereas the direct effect was not significant (B = −.03; p = .84; 95%CI: −0.35, 0.29). This indicated that good service recovery improved the participants’ intention to revisit via consumer affinity. Therefore, H2 was supported again.

Study 2a MethodsIn order to confirm the boundary condition (H3), we conducted an additional study. In Study 2a, we used the same scenarios as in Study 1a except for the country in which participants experienced a service failure. The scenarios used in this study describe a service failure that occurred in South Korea. Although several Japanese do like Korean culture, recently economic and political dissonance have become fiercer between the two countries. Our pretest results indicated that Japanese people have higher animosity toward South Korea on average. Compared to the Germany case, we can examine whether the effect of service recovery disappears when the consumer originally had a more negative impression toward the country.

An online experiment was conducted in Japan in October 2020 (N = 480). Using the same three attention check questions, we deliberately eliminated inattentive respondents. After this screening process, 343 (female = 159, male = 184, mean age = 44.69 [SD = 13.74]) respondents remained. Scales were identical to those in Study 1a, but the country was changed from Germany to South Korea.

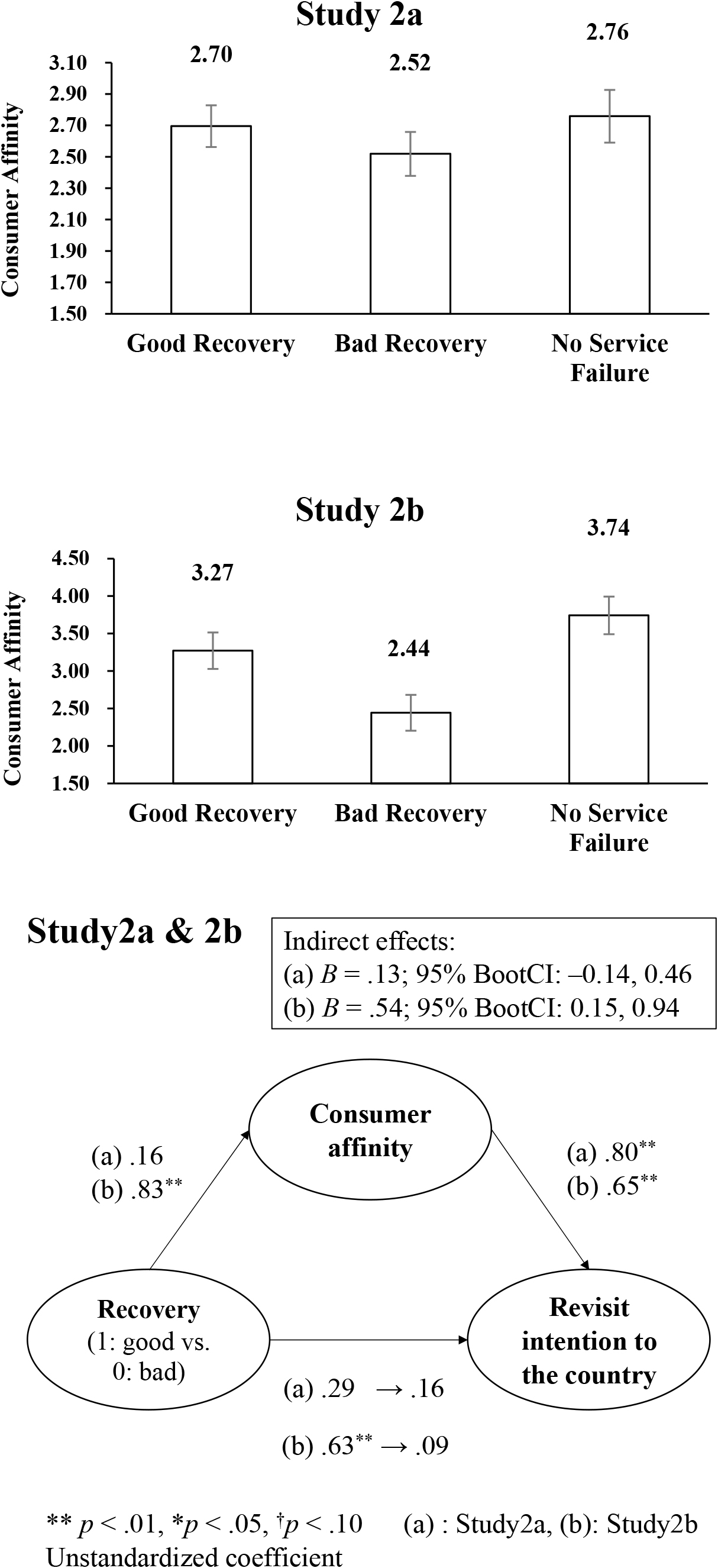

ResultsWe conducted a one-way ANCOVA in the same way as in Study 1a (see Figure 3). The overall model was significant (F(4,338) = 11.86, p < .00, ηρ2 = .12). The results revealed that the main effects of travel experience to South Korea (F(1,338) = 9.89, p < .01, ηρ2 = .03) and perceived service failure severity (F(1,338) = 22.12, p < .00, ηρ2 = .06) were significant. However, the main effect of service recovery on affinity was not significant (F(2,338) = .69, p = .50, ηρ2 = .00). There were no significant differences in any of the combinations. This result is consistent with our prediction.

Results of Study 2.

To examine the mediating effect of consumer affinity, we initially regressed revisit intention on service recovery with covariates. The result indicated that the effect of service recovery on revisit intention was not significant (B = .29; p =.15). Also, in the mediation test (Hayes, 2018, model 4), the direct effect (B = .16; p =.28; 95% CI: −0.13, 0.46) was neither a significant nor an indirect effect (B = .13; 95% BootCI: −0.14, 0.40). Therefore, we could not confirm the mediating effect of consumer affinity. These results support H3.

Study 2b MethodsWe examined H3 using another study (February 2020) that used the same scenario and scales as in Study 2a (N = 99). However, we did not apply control variables. After eliminating the inattentive samples, the final usable sample size was 41 (female = 24, male = 17, mean age = 42.93 [SD = 12.29]).

ResultsGiven the sample size was relatively small, we conducted a nonparametric test. Friedman test for three pairs yielded a significant difference (χ2(2) = 39.65, p <.00). Then, Wilcoxon tests were run to follow up on this finding. The results showed that good service recovery generates higher consumer affinity than bad service recovery (z =4.26, p < .00, r = .56). Contrary to Study 1a, the consumer affinity score was higher in the no service failure condition than in the good service recovery condition (z =−3.14, p < .00, r = −.41).

We then conducted a mediation analysis using the MEMORE Macro (model 1; Montoya & Hayes, 2017) with the good- and bad service recovery samples. The results revealed that the indirect effect of service recovery on consumer affinity did not include zero (B = .54; 95% BootCI: 0.15, .94), whereas the direct effect was not significant (B = .09; p = .50; 95% CI: −0.18, .36). Thus, good service recovery improves intention to revisit via consumer affinity. Therefore, H3 was not supported.

Study 3 MethodsA scenario-based experiment was conducted to test H4 and H5 and to replicate H1. We employed a 2(process recovery: high vs. low) × 2(outcome recovery: high vs. low) between-subject design. In addition, we included the no failure scenario (i.e., good service scenario) as a control group. Except for the control group, each scenario made participants imagine the situation of a severe flight delay that occurred in an airport in Germany while traveling (adapted from McCollough et al., 2000). Unless participants immediately booked another flight, they would arrive in Japan at midnight and have to spend the night at the airport.

For those participants in the high (low) outcome recovery scenario group, the staff did (did not) offer a €20 meal coupon for the airport and a €150 voucher for the airline as compensation for the inconvenience. For those participants in the high (low) process recovery scenario group, a German airline staff member listened to them with tender care (in a businesslike manner), offered a sincere apology twice (did not offer any apology), and helped arrange another flight (refused the request to help book another flight and left participants to arrange it themselves). In the control scenario, there was no problem and the participants enjoyed the flight. As for the relationship with the scenarios used in Study 1 and Study 2, the scenario in which both outcome recovery and process recovery were high corresponded to good service recovery while the scenario in which both outcome recovery and process recovery were low corresponded to bad recovery.

An online experiment was conducted by a professional research firm that recruited 800 respondents in Japan in September 2020. To ensure manipulation validation and attention check, this study eliminated inattentive respondents who answered three plain yes/no questions incorrectly at least once (“I used a Japanese airline”; “The airline employee gave me a meal ticket and a discount coupon”; “The airline employee helped me rebook my ticket”). After these respondents were eliminated, the final sample size was 465 (female = 243, male = 222, mean age = 44.82 [SD = 14.07]).

We measured consumer affinity, warmth, and competence (see Appendix). A travel experience to Germany in private life (dummy coded variable, 1: Yes, 0: No) and perceived service failure severity were also measured as control variables.

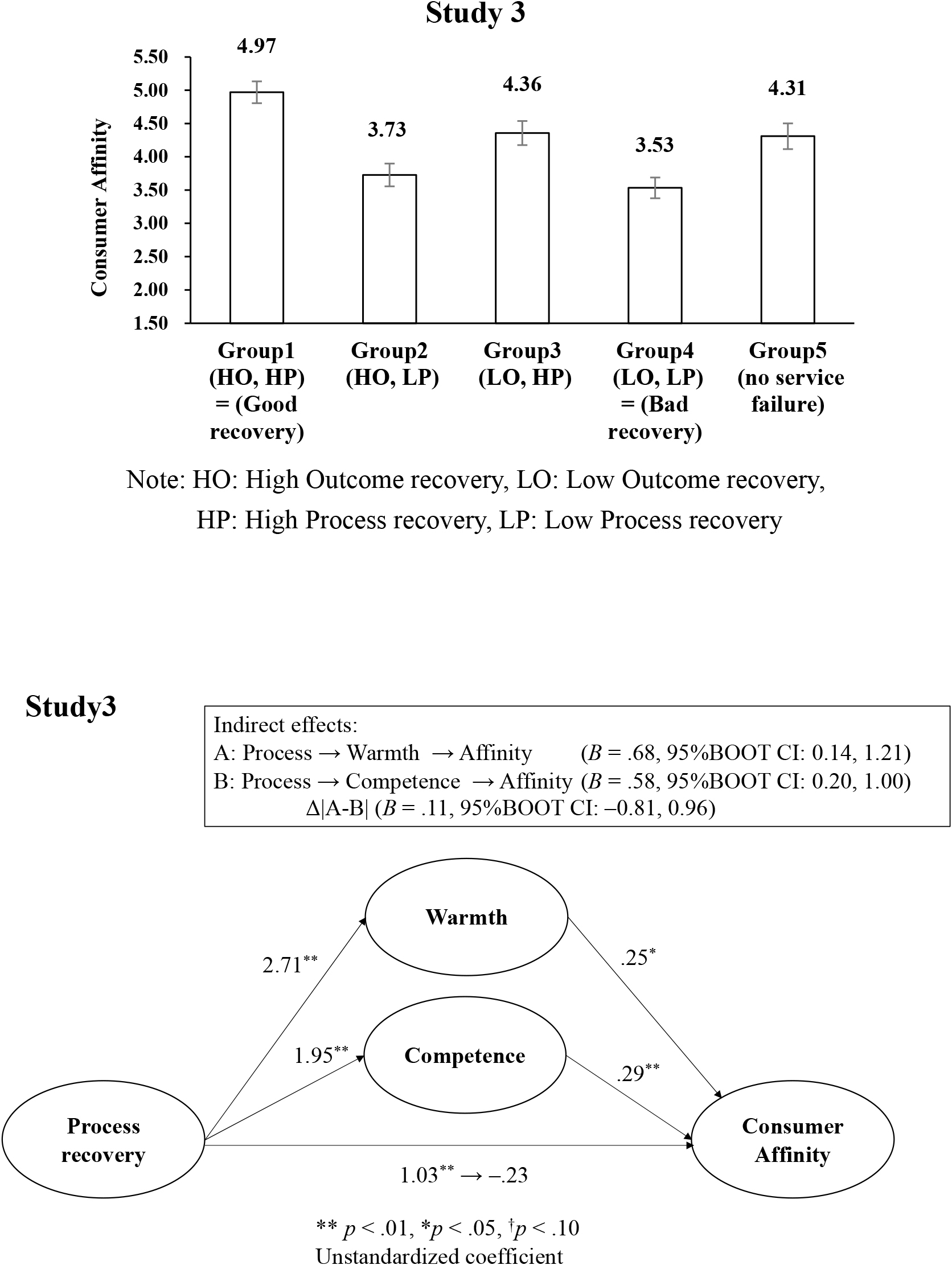

ResultsFirst, in order to replicate H1, we conducted a one-way ANCOVA with consumer affinity as a dependent variable using five scenarios. The results indicated that the conditions of service recovery were significant (F(4,458) = 15.89, p < .00, ηρ2 = .12). Planned contrasts revealed interesting results (see Figure 4). Here, to compare among the good service recovery condition, bad service recovery condition, and control condition, we focused on the differences among Group 1 (high outcome, high process), Group 4 (low outcome, low process), and Group 5 (no service failure). The mean of consumer affinity of Group 1 was higher than that of Group 4 (MGroup1 = 4.97 vs. MGroup4 = 3.53, p < .00, d = 1.03). Thus, good service recovery improves consumer affinity more than bad service recovery. More importantly, the mean of consumer affinity of Group 1 was also higher than that of Group 5 (MGroup1 = 4.97 vs. MGroup5 = 4.31, p = .02, d = .48). This result suggests that good service recovery engenders higher affinity than no service failure (i.e., good service). Namely, the service recovery paradox was confirmed. Therefore, H1 was fully supported.

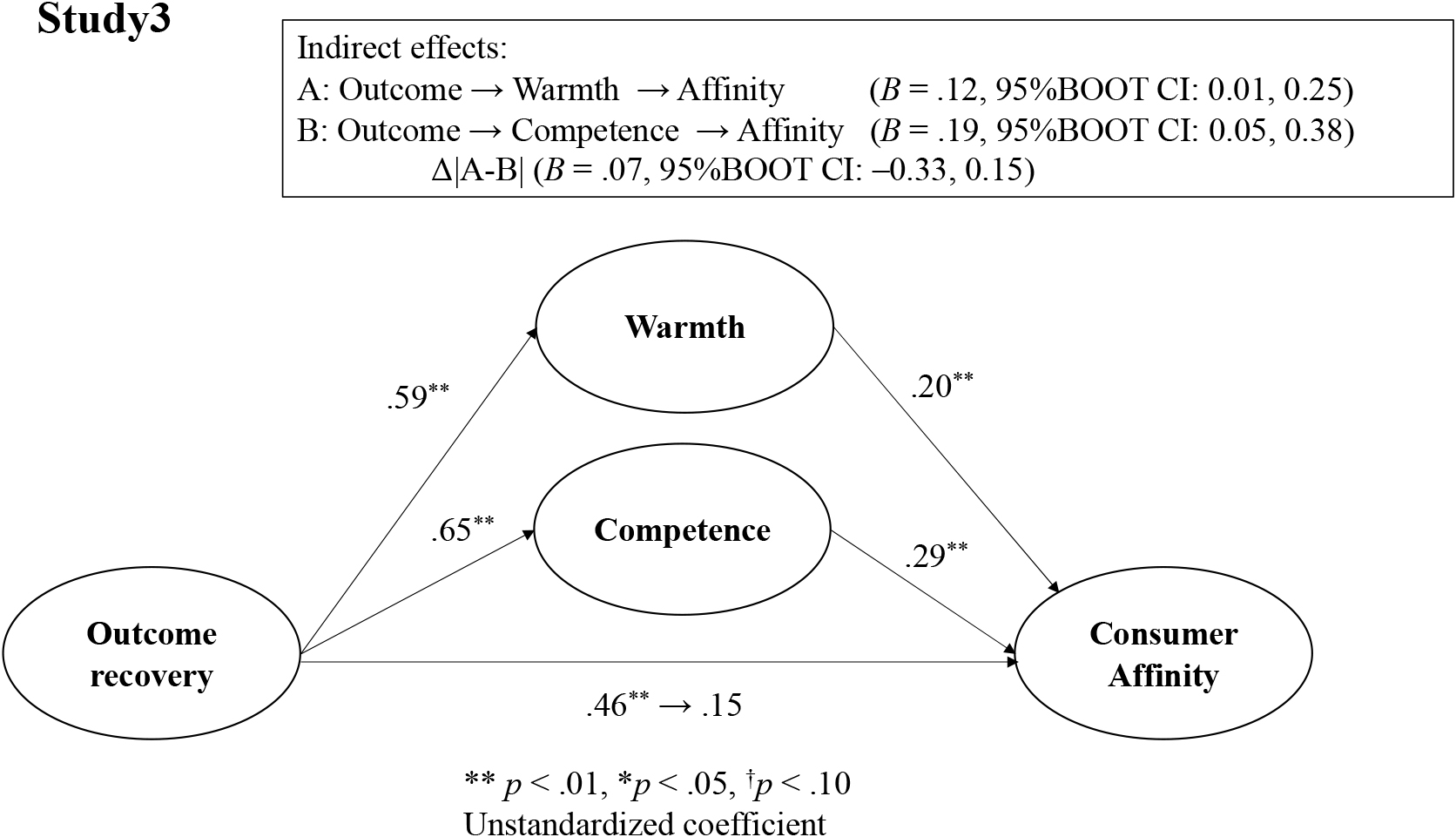

Results of Study 3.

Continued

We tested H4a (process recovery→warmth→affinity) by excluding the control scenario (n = 392). We coded process recovery (1 = high, 0 = low) as a dummy variable and regressed consumer affinity on process recovery with travel experience to Germany and perceived service failure severity as control variables. The results indicated that the overall model (R2adj. = .20, p <.00) and the main effect of process recovery are significant (B = 1.03, p < .00). A parallel mediation analysis was then performed using PROCESS (model 4; Hayes, 2018). The direct effect of process recovery on consumer affinity was not significant (B = −.23; p = .25; 95% CI: −0.61, 0.16) whereas both the indirect effect of process recovery on consumer affinity via warmth (B = .68; 95% BootCI: 0.14, 1.21) and the indirect effect via competence (B = .58; 95% BootCI: 0.20, 1.00) were significant. Although the indirect effect of warmth was higher than that of competence, the difference was not significant (B = .11; 95% BootCI: −0.81, 0.96), not supporting H4a.

Next, in order to examine H4b (outcome recovery → competence → affinity), we coded outcome recovery (1 = high, 0 =low) as the dummy variable and regressed it on consumer affinity with control variables. The results indicated that the overall model (R2adj. = .11 p <.00) and the main effect of outcome recovery is significant (B = .46, p < .01). A mediation analysis showed the insignificant direct effect of outcome recovery (B = .15; p = .24; 95% CI: −0.10, 0.40) whereas indirect effect via competence (B = .19; 95% BootCI: 0.05, 0.38) and warmth (B = .12; 95% BootCI: 0.01, 0.25) were significant. Although the indirect effect of competence was higher than that of warmth, the difference was not significant (B = −.07; 95% BootCI: −0.33, 0.15), not supporting H4b.

Finally, to compare the effect of warmth and competence on consumer affinity (H5), a regression analysis was run (R2adj = .345, p <.00). Contrary to our prediction, the main effect of competence was larger (B = .30, p < .00) than that of warmth (B = .20, p < .01), after controlling for travel experience to Germany and perceived service failure severity. For a more detailed comparison, the relative weight analysis was conducted using RWA-Web (Tonidandel & LeBreton, 2015). The results revealed that competence and warmth accounted for 42.29% and 39.29% of the variance of consumer affinity, respectively. As a result of the bootstrap estimation, the relative weight of warmth did not differ from that of competence (95%CI: −0.04, 0.05). Therefore, H5 was not supported.

Single Paper Meta-AnalysisTo confirm the robustness of our fundamental hypothesis (H1), we conducted a single paper meta-analysis (McShane & Böckenholt, 2017) using samples from Study 1a, Study 1b, and Study 3 (Groups 1, 4, and 5)8). The results supported the difference between good service recovery and bad service recovery (estimate = 1.02, SE = .28, Z =3.67, p < .00), whereas there was no difference between good service recovery and the no service failure condition (estimate = −.09, SE = .28, Z = .33, p = .37). Therefore, H1 was partially supported again.

This study provides three important theoretical contributions. First, we provide empirical evidence regarding the antecedents of consumer affinity. Although prior research showed interesting insights from using the qualitative method (Asseraf & Shoham, 2017; Oberecker et al., 2008) and correlation analysis (Bernard & Zarrouk-Karoui, 2014), the antecedents examined were difficult for marketers to control, leading to challenges in deploying business practice. Furthermore, the theoretical foundation was not established. Oberecker et al. (2008) suggested that consumer affinity engenders the process of inclusion of a focal foreign country into in-group status through personal experiences based on social identity theory (Tajfel, 1982). However, what exactly the process of inclusion into the in-group means was unclear. This study showed that a good service recovery can improve consumer affinity based on scenario experiments. Also, drawing on emotional attachment theory (Bowlby, 1979) and the concept of warmth and competence (Güntürkün et al., 2020), we explained that, when consumers encounter service failure, they seek support from others to mitigate their insecurity. If they are offered excellent service recovery by service providers, consumers experience an affective bond with them called consumer affinity. This consumer affinity for a person in a foreign country may transfer to a consumer affinity for a focal foreign country. We also showed that two dimensions, warmth and competence, intervene in the process of consumers forming their impressions of service providers. This study corresponds with the important remaining challenge in international marketing.

Second, we contribute to the study of international tourism study by showing the importance of service recovery and consumer affinity in ICSEs. The intention to revisit a destination country is an important metric in international tourism research, so numerous studies have attempted to identify its antecedents (Afshardoost & Eshaghi, 2020). However, to the best of our knowledge, the effects of service recovery have not yet been examined. This lack is surprising, because the element is likely to produce further service failures in ICSEs due to the greater cultural distance that may exist between the customer and the service employee (Sharma et al., 2009; Stauss & Mang, 1999). Our study revealed that appropriate service recovery not only elicits higher revisit intention, but also that this effect is mediated by consumer affinity.

Finally, we also provide useful insights into the service recovery research. Although the merits of appropriate service recovery have been examined from multiple perspectives (e.g., Gelbrich & Roschk, 2011; Tax et al., 1998), to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the influence on consumer affinity (except for Terasaki & Taketani, 2021) and intention to revisit the destination country. Shedding light on the new benefit, this study emphasizes the importance of conducting an excellent service recovery and facilitates further research on service recovery.

Practical ContributionsBeyond these important theoretical contributions, our study also offers practical implications. Increasing consumer affinity can have multiple positive effects on a country, such as a willingness to buy, greater investment intention (Oberecker & Diamantopoulos, 2011), and revisit intention (the current study). Thus, leaders in the hospitality industry and its policymakers should encourage service marketers and contact employees to offer good service recovery to increase consumer affinity and intention to revisit the country. To this end, it is important to develop excellent practice guidelines (e.g., Japan Finance Corporation, 2019), precise standards, and certification systems for service quality, clearly emphasizing the role of service recovery. Although the service recovery paradox that relates to consumer affinity cannot be confirmed by a single paper meta-analysis, there was no difference found between good service recovery and the no service failure condition. In other words, good service recovery still remains important in terms of preventing the formation of negative impressions visitors form about their destination country.

Focused clear efforts to support foreign tourists in filing complaints to their service providers are also important. If foreign visitors experience service failures and are unable to file complaints due to language barriers, then the opportunity for service recovery is also lost. In that regard, in Japan, the National Consumer Affairs Center of Japan launched a “Consumer Hotline for Tourists” in December of 2018. They should increase both awareness and better accessibility to foreign tourists of this hotline through various media (e.g., LIVE JAPAN PERFECT GUIDE).

Limitations and Future Research RecommendationsSeveral limitations should be considered. First, it would be meaningful to consider moderator variables or boundary conditions. For example, one possible explanation for the lack of a service recovery paradox is the influence of industry. A meta-analysis revealed that studies conducted in the hotel industry reported a higher effect size (.495), but those in restaurant studies (.044) or other service categories (−.057) were quite small (De Matos et al., 2007). The scenario used in Study 1 described a service failure in a restaurant, which could be the reason the recovery paradox did not occur. Indeed, Study 3 confirmed it in airline service context. Second, future research should address more types or levels of service recovery and examine their impact on consumer affinity. For example, is there also a nonlinear effect of compensation level (i.e., amount of compensation) on consumer affinity as in the case of consumer satisfaction (Gelbrich, Gäthke, & Grégoire, 2015), or do the effects vary depending on the type of resource for which consumers are being compensated (Roschk & Gelbrich, 2014)? Finally, future research should confirm the validity of findings in this study. In our research, the participants of experiments were only Japanese; thus, it is necessary to examine whether the same results can be obtained with Westerners. In addition, we adopted a scenario-based experiment as our methodology. Future research should confirm our results using real data to ensure ecological validity. Furthermore, we collected the data in February, September, and October 2020, and the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on responses (e.g., revisit intention to a foreign country) should have been inevitable. Future research also should consider the potential effect of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The authors would like to thank the editor and anonymous reviewers for constructive and helpful comments during the review process. This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers JP17K13811, JP20K13621, JP20K13628.

| Consumer Affinity (α = 96a, 97b, 97c, 97d, 97e) |

|---|

| Oberecker et al. (2011) |

| About Germany [South Korea] |

| • Pleasant feeling |

| • Like |

| • Feelings of sympathy |

| • Captivated |

| • Feeling attached |

| • Love |

| • Inspired |

| Intention to revisit the country (α = 90a, 98–99b, 91c, 98–99d) |

| Stylos et al. (2016) |

| • I intend to travel again to Germanya, b [South Korea]c, d sometime within the next 2 years. |

| • I want to visit Germany [South Korea] again within the next 2 years. |

| • The possibility for me to travel to Germany [South Korea] within the next 2 years is high. |

| • Germany [South Korea] could be again my next vacations place. |

| Warmth (α = 98e) |

| Güntürkün et al. (2020) |

| The German staff is ... |

| • Friendly |

| • Trustworthy |

| • Good-natured |

| • Sincere |

| • Helpful |

| Competence (α = 96e) |

| Güntürkün et al. (2020) |

| The German staff is ... |

| • Competent |

| • Capable |

| • Efficient |

| • Intelligent |

| • Skillful |

| Perceived service failure severity (α =95a, 96c, 94e) |

| Roschk & Gelbrich (2017) |

| For me as a customer, the failure ... |

| • is significant |

| • is major |

| • is severe |

| • causes a lot of inconvenience |

Note: All items were translated and adapted to fit the context of our studies. Each item was measured on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from (1) strongly disagree to (7) strongly agree. The data for Study 1a and Study 2a were obtained at a time when international travel was restricted due to the COVID-19 pandemic. To take this into account, we modified the wording of the revisit intention scale from the original version (within the next 2 years) to “someday”.

a Study 1a b Study 1b c Study 2a d Study 2b e Study 3