2022 Volume 10 Issue 2 Pages 38-57

2022 Volume 10 Issue 2 Pages 38-57

In Algeria, people with disabilities often struggle with the inaccessibility of cities. These problems are related to accessibility and physical barriers in the urban environment, and have a negative impact on the lives of people with disabilities, who are prevented from carrying out daily tasks and from moving freely in attractive and desirable places. This paper aims to examine the correlation between the accessibility and attractiveness of public spaces for people with disabilities. It analyses both the factors influencing their itinerary choices in public spaces and the impact that the spatial and social dimensions of the urban environment may have on their daily movements. This paper’s qualitative analysis begins with an in-situ survey conducted in the city centre of Algiers; it looks at how people with disabilities use public spaces, using an analysis based on commented walks as well as interviews with a group of disabled people. The second part of the paper focuses on a description of the study case, using space syntax techniques and depthMapX software. This analysis allows us to ascertain both the level of accessibility of the Algiers public space, and the parameters influencing the mobility of people with physical disabilities. It reveals that people with disabilities lack optimal travel choices, and that their movements are determined by the physical accessibility of the space, rather than by its attractiveness and/or usefulness.

Public space sits at the heart of all concerns and planning policies, with accessibility and mobility being fundamental elements of its attractiveness and durability. It forms the main core and the urban “framework” for the creation of a space that will encourage people to use the city, and experience it in a particular way (Hillier, 1996). Urban mobility is essential to social integration; increasing its potential allows for social and economic progress as well as the emancipation of individuals by creating new possibilities for them (Cadestin, Dejoux, & Armoogum, 2013). This increase in freedom and social inclusion can be accomplished through improved urban accessibility which corresponds to the possibility of crossing a space to reach a destination (Church & Marston, 2003).

In Algeria, the inaccessibility of space limits the mobility of people with disabilities (Hacini, Bada, & Pihet, 2019) and relegates them to the margins of society (Slimani & Boudjemline, 2016). It contributes to the problems of social segregation, discrimination, and insecurity they face, leading to their social exclusion and the deterioration of their health, both physical and psychological. This in turn can exacerbate their sense of “incomplete citizenship” (Imrie & Hall, 2001), increasing the burden of their physical disability and potentially leading to their becoming more reserved, introverted and ultimately more dependent. This is a universal problem concerning a large part of the population of every country in the world. Algeria alone has 280,000 physically disabled people (National Office of Statistics, 2008). These problems are the result of a lack of the sort of inclusive design that would take into consideration both the needs of people with disabilities and a failure to comply with the urban and architectural rules and standards in force.

This study looks into the movement of people with disabilities in the built environment within the core city centre of Algiers. It explores how urban configuration influences choice of itineraries and evaluates both the accessibility and the attractiveness of publics spaces. The study aims to understand the mobility problems encountered by people with physical disabilities in reaching attractive spaces and opportunities; that is, their ability to fully enjoy all that a specific place has to offer.

More than one billion people (which is 15% of the world’s population) live with disabilities making this the largest minority in the world (WHO, 2011). The World Health Organization has defined “disability” as “a generic term for impairments, activity limitations or participation restrictions. It refers to the negative consequences of the interaction between an individual (having a health problem) and the contextual factors in which he/she evolves (personal and environmental factors)” (WHO, 2001). Having a disability means facing challenges and complications when performing daily tasks; these difficulties are a result of combined personal and environmental factors (Victor, Klein, & Gerber, 2016). This situation defines the problem of accessibility, which occurs when there is a mismatch between the individual user characteristics and environmental specificities (Goodley, 2016).

Among the different definitions of accessibility, two stand out. The first is geographical or spatial accessibility (Litman, T. A., 2003), which describes the ease of reaching a space or activity, and the spaces that are connected and integrated into the urban network (Bocarejo S & Oviedo H, 2012; Chaloux et al., 2019; Geurs & Halden, 2015). The second definition concerns physical accessibility, which is defined by facilitators or barriers to accessing a place, and focuses on barriers in the built environment (Castrodale & Crooks, 2010; Heylighen, Van Doren, & Vermeersch, 2013). This definition relates directly to people with mobility limitations, such as those with disabilities. It looks at the impact the built environment can have on their mobility (Grosbois, 2008; Imrie, 1996).

Previous studies on accessibility have observed a distinction between reaching a space, access to opportunities, and ease of mobility, as well as the physical limitations of a place. Although accessibility has been approached from different perspectives, this study addresses the spatial dimension while linking it to socio-political dimensions in a cause and effect relationship. Environmental elements may be facilitators, obstacles, or neutral (Fougeyrollas et al., 1998). A distinction is thus now made between ‘disabling’ and ‘enabling’ environments (Preiser & Smith, 2010). This study adopts the definition of accessibility in its universal form with the concept of universal design, which seeks harmony in human-environment interaction and supports the idea that the environment must be adapted to all users, regardless of their physical and socio-economic situation (Iwarsson & Ståhl, 2003).

Urban Attractiveness for People with DisabilitiesHansen (1959) defines accessibility as potential for interaction and access to opportunities. There have been other definitions since, but most common are those defining accessibility as ease of access to an activity, place, or mode of transport (Dalvi & Martin, 1976). Morris, Dumble, and Wigan (1979) further explored access to city-based activities and amenities. Handy and Niemeier (1997), who studied the layout and quality of activities located at potential destinations, defined accessibility by the spatial distribution of these destinations.

Planning studies focus on the physical elements of the space and do not take into account its attractiveness or utility. Beyond these physical elements, the contextual and preferential characteristics of the individual are also ignored. Church and Marston (2003) argue that service users, given a choice, do not necessarily choose the nearest available activity. The choice will be affected by size or attractiveness of the activity site, distance, and the modes of travel available. Boumezoued, Bada, and Bougdah (2020) assume that an urban space affects users positively when it all five senses are stimulated. These stimuli can be different for people having different abilities (Golledge, 1993), who will use the same space differently. User-environment interaction can be a determining factor for a person with a disability in reaching the activities and opportunities present within a space. Restrictions to ‘normal’ activities within a city lead to social exclusion (Titheridge et al., 2009); such restrictions to activities are often due to physical barriers in the built environment (Slinn, Matthews, & Guest, 1998). Church and Marston (2003) developed the study of the chain of mobility by measuring relative access. This approach allows a link to be made between differences in user accessibility in relation to their physical abilities. In one example, the study showed that the effort made by a person in a wheelchair is 5.25 times higher than it is for an ambulatory person on the same path. Similarly, Vale et al. (2017) used the concept of accessibility disparity to measure accessibility, using the spatial network to calculate spatial connectivity. The results show a disparity in access to activities between people with disabilities and people without disabilities.

According to planning and tourism studies, urban attractiveness can be defined as the capacity of a place to satisfy the needs and objectives of its users plus factors that influence their decision-making (Ariya, Sitati, & Wishitemi, 2017; Vengesayi, Mavondo, & Reisinger, 2009). These factors are related to space quality, which includes amenities, services, and facilities which should be universally designed to suit all users. These constitute what Litman, T. (2007) called “the opportunities in a place”, which are a driving force for urban attractiveness. In this study we will relate physical accessibility to the attractiveness of a place, to see how people with disabilities navigate between these two aspects of space.

The Urban Configuration and Its Influence on the MovementThe urban configuration was studied using space syntax; several studies have shown that this can predict the use of space. Its main measures are integration (Hillier & Hanson, 1984; Hillier et al., 1993; Law, Chiaradia, & Schwander, 2012), connectivity (Hillier et al., 1986; Choi & Sardari, 2012) and visibility (Bada, 2012), and it assumes that the most integrated and connected spaces will necessarily be those most frequented, which possess strong urban attractiveness (Hillier et al., 1993; Hillier, 1996; Hillier & Iida, 2005; Major, Stonor, & Penn, 1998; Penn et al., 1998). Space syntax is based on the principle that urban configuration has an impact on movement through the concept of natural movement; it also impacts land use, distribution of activities and other social phenomena (Hillier et al., 1993; Hillier & Iida, 2005). The more attractive spaces are, the more the concept of natural movement applies to them, and the more a ‘magnet’ effect applies to such spaces as they attract more and more movement (Khorsheed, Zuidgeest, & Kuffer, 2018).

This method has also been studied in terms of the use of space by so-called ‘vulnerable’ populations. The study by Heitor et al. (2014) investigates the accessibility of the university campus for people with disabilities. It combined syntactic measures with commented walks and the level of effort. Results showed that poorly connected spaces created both barriers to accessibility and ‘black spots’ that hindered the movement of people with disabilities. Belir and Onder (2013) conducted a study on the spatial cognition of visually impaired people in malls. It combined cognitive map methods and observations with the space syntax method, and explored the impact of location features and markers on the navigation of visually-impaired people. The results have shown the importance of sensory and structural landmarks to navigation in spaces by people with disabilities.

Algiers is the administrative, political, and economic capital of Algeria. In 2015, it had more than three million inhabitants ( www.wilaya-alger.dz), making it the country’s most populated city. It is home to more than 200,000 people with disabilities (National Office of Statistics, 2008). Algiers has, at different points throughout its history, experienced occupation, and this has led to the juxtaposition of contrasting urban fabrics. The city-centre has a ‘Haussmanian’ French fabric that was developed in the funnel between the sea and the old Arab-Berber medina ‘Casbah’ of the mountainous heights. Both this mixing of different urban fabrics and its location within the city contribute to the richness of its cultural, architectural, and overall landscape. This morphological site makes the city-centre a succession of tiers, from lower to upper Algiers (Figure 1). The amphitheatrical effect of this part of the city currently represents one a major constraint to urban functioning for soft mobility, because the topography has resulted in the creation of steep slopes and urban staircases and steps at every street corner.

Figure 1. Aerial views of Algiers

(Documentary: Alger vu d’en haut, Yann Arthus Bertrand; Annotations: author)

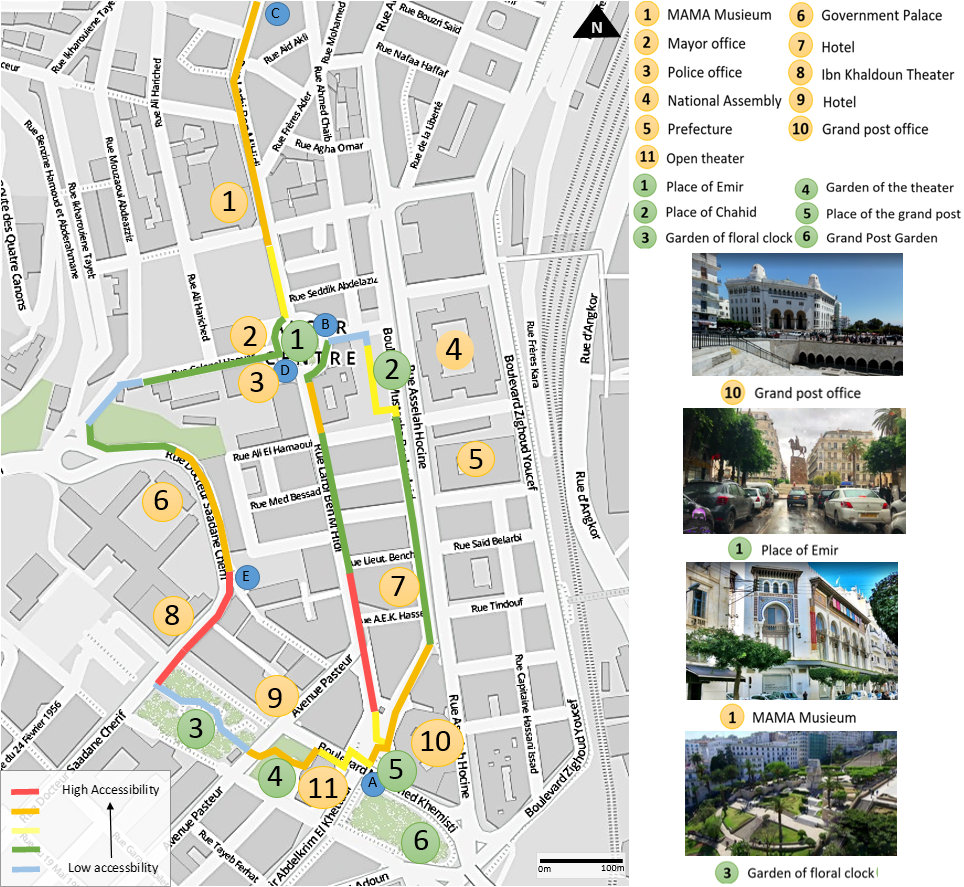

Because of the historical character of the urban fabric, the built environment is old and has obstacles due to the deterioration of certain places; it is not necessarily well-suited to modern mobility. The city centre is of great importance to the structure of the Algerian capital. Many of governmental facilities are located in the city-centre, as well as very important tourist and cultural facilities, and public squares (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Algiers city centre site analysis (Source: Author, OpenStreetMa)

In addition to these geographical constraints, there are also other constraints, created by the extreme densification of the urban fabric as well as the high population density. A rural exodus in search of employment and security has made Algiers a cosmopolitan city that is home to people from a wide range of social backgrounds, regions, and cultures. Use of public space is very intense “the streets have a life” and this provides both quality and attractiveness. It is on these streets that social interaction and commerce happen, and both are vital to the city’s dynamic and effervescent quality. Given the social diversity, this study aims to see whether people with disabilities are also able to find a place in central Algiers. The study perimeter is located in the heart of the city-centre (Figure 2), around Boulevard Ben M’Hidi one of the city’s most important axes. This boulevard is filled with shops and amenities and is a busy meeting place, connecting as it does three of Algiers’ main reference points: The Grand Post Office, the Emir Square, and the MAMA Museum.

Implementation of the Survey ProtocolAlthough several accessibility measures (see Church & Marston, 2003; Vale et al., 2017) have been developed in the past, these have been criticized for their failure to take into account socio-economic, geographical and political context. This is why our study has chosen to use a mixed method at once qualitative and quantitative (Bendjedidi, Bada, & Meziani, 2019) to measure physical accessibility (Grosbois, 2008; Imrie, 1996). The study was conducted from the users’ point of view (Kvale & Brinkmann, 2009; Bromley, Matthews, & Thomas, 2007; Lid & Solvang, 2016), seeking indications of perceived accessibility (Lättman, Olsson, & Friman, 2018) rather than measured accessibility (Church & Marston, 2003).

Qualitative methods entail the use of semi-directive interviews and the commented walks method, to achieve an overview of how people with disability use space. Quantitative methods entail the use of space syntax techniques to get an idea of the axis having most characteristics to attract movement. Finally, an overlaying of the results will show whether people with disabilities choose the axis which attracts most movement, or not.

The study begins by determining the level of physical accessibility of the study area, before exploring attractiveness based on the criteria given by Krešić and Prebežac (2011) and Formica (2002). These are quality of spaces and the built environment, usefulness of spaces, activities, amenities, shops, cultural and touristic places, public transport, vegetation, rest places and strolling spaces. Since attractiveness is a subjective notion, we will link the attractiveness factors expressed by the participants to the space syntax modelling method.

Semi-directive interviewsSemi-directive interviews were conducted in order to get an idea about use of space by people with physical disabilities and the parameters that influence their movements. 60 people having innate or acquired physical disabilities were interviewed before the commented walks. These people were identified with the help of associations, social networks, and mutual friends. We gave them appointments at the place most convenient for them which was most often their home, at a cafe, or on premises belonging to a charitable organisation. The points discussed were divided into four sections, all of which focus on the theme of urban accessibility:

• Identity of the interviewee

• Use of public space

• Navigation and orientation in the public space

• Perception and representation of the city.

Of these 60 people, 30 are residents of the city of Algiers. We conducted a textual analysis with the Nvivo software of the speech of these 30 people to see the topics and key words emerging in their speech.

The Commented walksThese interviews were followed by commented walks, based on the method developed by Thibaud (2001). This allows for closer recreation of situations in which people use public space in their day-to-day lives. The purpose of using this method was to see how people with disabilities navigate the urban environment, and how they choose their itineraries.

Six pathways within the case study perimeter, featuring various urban characteristics, were selected for the commented walks. Each pathway was divided into segments, Figure 3 show the selected pathways for the study. Two researchers accompanied each disabled person along the selected pathways: one talking and recording audio of the interviewee’s statement, and the other serving as a camera operator. This method was conducted with 6 volunteers (1: manual wheelchair user, 2: electric wheelchair user, 3: amputee using a prosthesis, 4: semi-ambulatory person, 5: semi-ambulatory person using crutches, 6: elderly person using a cane). These volunteers were drawn from the population of 60 people with whom the interviews were conducted and who were not residents in Algiers. Each participant walked along five paths, so that we had a total of 30 commented walks.

Figure 3. The pathways selected for the study (Source: Author, OpenStreetMap)

Since participants were not familiar with the places, paths were not imposed. A starting point and destination point were given (points A, B, C, D, E in Figure 3), and if participants started getting lost, they were provided with a reference point to help them reach their destination. The paths were the same for all participants, who were free to make their own trajectory decisions within the given path in order to reach the given destination. For example, some used a footpath on the left while others used a footpath on the right.

Participants were asked to describe how they felt during the walk, explain their navigation choices, and assess the sense of comfort and the level of ease of movement (Table 1). During the commented walks, at the end of each segment, participants were asked to describe their feelings on three scales of 1 to 5 (Table 1). The first asked about their comfort during the journey. The second was an adaptation of Borg’s Effort Perception Scale (Borg, 1982). Lastly, we devised a third scale aimed at getting an overview of the attractiveness and utility of the space used, as perceived by participants. This scale was based on urban attractiveness factors deduced from the literature described above. To complete this evaluation, we also observed participants’ reactions and body language, as well as what they said.

Table 1. Scaling for the collection of participants’ feelings during commented walks.

| Scale | Comfort | Effort | Attractiveness / Utility |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Immobility | No effort/ very easy | I feel discomfort in this space (fear) |

| 2 | Travel assisted by an able-bodied person | Low effort/ easy | I don’t like this space (no activities) |

| 3 | Difficult travel, major discomfort | Moderate/medium effort | This space leaves me indifferent (no benefit) |

| 4 | Movement with slight discomfort | Great effort/difficult | I feel good in this space (pleasure) |

| 5 | Easy movement effortless | Maximum effort/ very difficult | I want to come her again (Useful and pleasant) |

The space was analysed quantitatively, using spatial configuration values and graphs based on space syntax techniques. This method was used to measure both geographical accessibility and urban attractiveness, as well as to see whether the movement of people with disabilities could be predicted.

DepthMapX software was used to generate the syntactic measures, alongside an axial map, which is a two-dimensional representation of space, capable of determining the longest straight lines for pedestrians to follow that cross the convex spaces connected to each other. The measures calculated in the analysis are:

The space syntax is useful in this study, since in previous research cited above, it has been effective in analysing the behavior and movements of city users.

The semi-directive interviews were transcribed on the basis of the topics raised by participants (Table 2). Three main themes stood out and occupied the majority of the interviews: Accessibility of the urban environment (mentioned in 40% of interviews), Urban attractiveness and opportunities (mentioned in 35% of interviews), and Socio-political factors (mentioned in 25% of interviews). These themes were broken down into sub-themes, which were in turn divided into the points discussed. Most interviews focused on continuity of space (Table 2); 80% of participants think that there is a problem of accessibility in the Algerian public space. Public transport is described as both inaccessible and impracticable, with bus steps being too high, and bus stops too few. A lack of accessibility to buildings and shops was also mentioned. Participants pointed out steps that hamper their ability to carry out everyday activities because they are not compliant with urban standards. Slopes were also mentioned, because as participants explained, steep slopes create difficulties of movement (Table 2).

|

Accessibility of the urban environment 40% |

Physical factors 20% |

Paths, Obstacles, Steps… Transport, Furniture, Parking… Topography, Orientation… |

|---|---|---|

| City functioning 12% | ||

| Urban form 8% | ||

|

Urban attractiveness and opportunities 35% |

Utility 10% |

Quality/price, Diversity, Jobs… Gardens, Squares, frequentation. Shops, Services, Sport, Health… Functional mix, Arrangement… Aesthetics, Style, Harmony, Symbolism, Maintenance… |

| Strolling 5% | ||

| Amenities 10% | ||

| Functional quality 5% | ||

| Urban and architectural quality 5% | ||

|

Socio-political factors 25% |

Social interaction 10% |

People staring, Help, Exclusion... No romantic life, Financial… problems, Depression, No job… Segregation, Financial … |

| Social and psychological problems 8% | ||

| Disability policy 7% |

The results of this method were mapped (Figure 4) to explain the variations in accessibility within the study area. These variations are described for each pathway as follows:

The level of accessibility expressed during the walk varies between 2/5 and 5/5 (Figure 4). From the Post Office Square to the beginning of the boulevard, the space is scored as 5/5 accessible, with the Flower Pedestrian Path at 4/5. Accessibility then decreases, becoming very weak at Emir Square at 2/5. This is mainly due to the lack of dropped kerbs to cross at junctions or cross from one side of the street to the other. 75% of participants pointed out the poor condition of the footpath and the inaccessible shops and buildings, as well as the steps used to access the square during the walk. Café terraces encroaching on the footpath were also singled out, along with the lack of reserved parking spaces for people with disabilities. During the walk, participants found this boulevard very pleasant, with high architectural quality, rows of trees for shade, and a diverse range of trade, consumption and services offered, as well as high frequentation and the presence of rest areas. Attractiveness was rated at 5/5 right along this pathway (Figure 4).

On the way to the Government Palace, the Floral Clock Garden was inaccessible to most participants (Figure 4), rating just 1/5 because of its many steps. This pathway also proved difficult to follow because of steep slopes in some places. It was judged pleasant, due to the quality of the public square and the layout of the garden. The lush planting and the rest areas were very much appreciated, resulting in an attractiveness rating of 4/5 for this pathway.

From the Floral Clock Garden to the Government Palace through to the Ibn Khaldoun Cinema, participants did not experience any particular hindrances; the pathway met their needs and was rated with good accessibility at 5/5 and 4/5 (Figure 4. However, towards the end of the pathway, accessibility fell to 2/5 because of a slope and an inaccessible alley which, in addition to being very narrow, had parked cars and litter on the footpath. To reach Emir Square, access to the upper level was via a monumental urban staircase that most participants were unable to use, lowering the accessibility rating to 1/5. In spite of its high accessibility ratings for the first two-thirds, this pathway’s attractiveness score was rated at just 2/5; the lack of stores, liveliness and vegetation was also pointed out. In general, participants did not much enjoy this fairly dull pathway.

This pathway proved to have poor accessibility, rated at 2/5 owing to footpaths that were not only too narrow but also had a deteriorated surface, as well as being partially blocked by obstacles such as dumpsters and parked cars. A public toilet was deemed inaccessible because access was via steps and a narrow path. This pathway was judged moderately attractive by participants, at 2/5 and 3/5 (Figure 4). Chahid Square was unpleasant owing to sun exposure and to the fact that the square cannot be accessed from the footpath because of a physical barrier. There was an average presence of stores, but this did not satisfy participants because the narrowness of the footpath restricted their use. The view of the lower area of Algiers city centre was appreciated.

One participant said, “I choose routes where there are least obstacles, even though I would like to go to places that are more pleasant.” Similar actions and testimonials were noted for 70% of participants. A cartographic transcription has been created (Figure 4), showing the level of accessibility of the spaces visited by participants (Morange & Schmoll, 2016). This map was drawn up using the accessibility index scale presented in the methodology section. This map shows that along all the pathways studied, accessibility ratings are uneven, varying between 1/5 and 5/5 (Figure 4).

Struggles faced by participants related mainly to obstacles in the urban space and a lack of mobility facilitators. Participants were hampered by footpaths (quality and type) and steps, confirming the results of our interviews. These elements strongly influence choice of itinerary, since 75% of answers to the question “Why this itinerary?” were “It is where I can go” or “There are no obstacles”. This situation limited the choice of itineraries for the commented walks, since users were unable to access spaces such as gardens, shops, and other facilities. 70% of factors pointed out by participants during the walk related to continuity of space in terms of physical obstacles, urban configuration and urban patterns (Table 2).

Figure 4. Accessibility level of the study area (Source: Author, Open Street Map)

Based on the feelings recorded during the commented walks, by asking questions and analysing the movements and body language of participants, we used the results from the scale of effort (Table 1 and the rating of accessibility (Figure 4) described above and plotted them onto graphs illustrating the evolution of the level of effort in relation to the accessibility of the space as a consequence of the distance travelled during the journey (Figure 5). These results were produced by averaging all the accessibility and effort indices collected, using the scales described above. In each graph (Figure 5), we note that there is an opposition between the rating of accessibility and the effort made. This relationship does become less clear for the last quarter of the journey, where the effort provided becomes more consistently strenuous. This is due to participant fatigue.

Figure 5. Ratings of effort and accessibility on each pathway (Source: Author)

20% of participant comments during the walk concern the influence of social interactions. People staring and other inadequate or unhelpful behaviours can embarrass participants. When pathways are busy, their field of vision is reduced and they can be afraid of being jostled.

Results of syntactic analysisFor the integration analysis, we applied the global analysis Rn (Figure 6), which studies each space in relation to the whole system and evaluates the relationship of each axis to all the other axes. This approach makes it possible to identify areas of integrated and segregated spaces for the purpose of studying the whole spatial structure and not just in relation to certain city spaces.

Figure 6. Integration analysis results (Source: Author, OpenStreetMap)

The global integration analysis Rn (Figure 6) gives a system-wide average integration value of 2.35. Pathways 1 and 2, AB-CD (Boulevard Ben M’hidi) have the highest integration value, at 4.57. This axis runs from Grand Post Office Square to Emir Square via the Floral Pedestrian Path along the Ben M’hidi Boulevard (Pathways 1 and 2, AB-CD). This strong integration continues after Emir Square, where, upon reaching the MAMA Museum, the value reaches 3.44 and continues to the north end of the boulevard. The Boulevard Benboulaid (Pathway 5, BA) has a medium and constant integration value along the whole length of the boulevard, with an average of 3.30. However, this value drops considerably in Chahid Square, where it reaches 2.65. On Pathway 3, AE (Boulevard Khemisti), in front of the Grand Post Office, the integration value is middling, at 3.61. This integration value falls on the side of the garden of The Green Theatre, and continues to decrease, reaching 2.41 within the garden itself. Pathway 4, ED (Dr. Saadane Street) has the lowest value of integration at 1.40, along with Ibn Khaldoun Cinema and the government palace (Figure 6).

Connectivity measures are consistent with global integration (Figure 7), so the average connectivity value of the entire system was calculated at 13.76. As with their integration values, Pathways 1 and 2, AB-CD (Boulevard Ben M’hidi), have the greatest number of connections, scoring 63. In contrast to its integration, Pathway 5, BA (Boulevard Benboulaid) has low connectivity values along with the entire Chahid Square, with an average value of 28 connections. Connectivity, reaches very high values at the Grand Post Office, then gradually decreases on the Boulevard Khemisti, AE (Pathway 3) which has 39 connections, through the garden of the flower clock to Dr. Saadane Street (Pathway 4, ED) where connectivity reaches its lowest score of 12 connections. The axis in front of the Ibn Khaldoun Cinema is the least connected system, with just 4 connections.

Figure 7. Connectivity analysis results (Source: Author)

These results show that participants with disabilities choose their destinations according to their accessibility from home. Itineraries must be both even and free of obstacles, even if this means taking a much longer route. By following this logic, they evolve preferred spaces for each of their activities (sport, work, relaxation, shopping). In the event that they are unable to find an accessible route from home, the corresponding activity is removed from daily life.

In the syntactical analysis, spaces having the strongest integration and connectivity values are those with both an attractive and a commercial character, like Boulevard Ben M’hidi; this boulevard space is home to high commercial, cultural and administrative activity (Figure 8). Field observations have shown that these areas benefit from strong frequentation and a high level of activity. Conversely, spaces with low values of integration (below 2.50) and connectivity (fewer than 30 connections) are unattractive; these are generally spaces that are less busy and have low commercial attractiveness. We transcribed the commented walks onto a map, using a colour code to classify the spaces from most to least pleasant (Figure 8). This map has been compared to both the accessibility map and the integration map.

Figure 8. Attractiveness / Accessibility comparison / Integration (Source: Author)

The comparison between the variables Attractiveness, Accessibility and Integration (Figure 8) confirms our observation that the most pleasant spaces are those that are both most integrated and most connected. For example, Pathways 1 and 2, AB-CD (Boulevard Ben M’hidi) have maximal integration (4.57) and maximal perceived attractiveness (5/5). However, these pleasant, attractive spaces are not the most accessible, as can be seen with Pathways 1 and 2, AB-CD (Boulevard Ben M’hidi), which have an average score of 3/5 in terms of perceived physical accessibility making them partially inaccessible for people with disabilities. Spaces having strong values of integration and connectivity have been considered spaces that people with a physical disability desire to frequent, based on the attractiveness and usefulness criteria; these are the axes where “they feel good”.

“This store does not have steps, so I could shop there.” With this comment, the participant highlights the fact that accessibility is the main criterion determining where they shop, rather than quality of goods and services, or price which are the main criteria for the majority of society. In examining the language, then the participant with reduced mobility says “I could shop there,” where most able-bodied people would say “where I want to buy stuff.” The problem is that people with physical disabilities are unable to make choices about which spaces they use on the basis of their attractiveness; instead, their choices are based almost exclusively on accessibility. This highlights the imperative need for urban accessibility to allow for the use of attractive spaces by people with disabilities. In some cases, these people are unable to frequent an attractive space even if they wanted to, due to the physical and sensory characteristics of the space in question in terms of urban accessibility. An elderly woman told us that she has to do her shopping in stores she does not like; she has no choice since only these are accessible to her. Given a choice, she would go to the mall where quality products are sold at a reasonable price, but the route to this mall is not accessible to her. Because she is unable to shop where she wants, she shops where she can, despite having to pay more.

The representation of attractiveness varies according to individual circumstances; certain inequalities for people with disabilities are exposed, in spaces such as shopping streets that, while seeming “ordinary” to able-bodied people, may be attractive to people with disabilities. These spaces are inaccessible to them, so that attractiveness can be a factor of accessibility and vice versa. The two concepts are inseparable, and where both are optimal, this can lead to the social inclusion of the disabled. Some otherwise very attractive spaces are full of obstacles, that render them inaccessible (when these obstacles cannot be overcome) to people with physical disabilities. In the study, it was assumed that people with disabilities move more towards accessible spaces than towards integrated ones because of lack of choice rather than active desire. For example, Emir Square was perceived by 80% of participants as attractive and pleasant, yet most were unable to access it because physical obstacles inhibited them from doing so. Despite having high values for both integration and connectivity, it is not frequented by people with physical disabilities not because they do not want to go there, but because they are physically unable to.

Factors of Inclusiveness to All Space UsersUnlike able-bodied people, people with disabilities require, in addition to an integrated and connected space (materialised by attractiveness), that a space be physically accessible. This requirement means total freedom of mobility according to their desires and needs. The survey results suggest that an inclusive space should be accessible, integrated, and connected. The following diagram represents this finding (Figure 9).

Figure 9.The conditions for achieving an inclusive space (Source: Author)

The social situation of people with disabilities is also affected by this; they are forced to circulate in spaces that do not suit their needs. Their mobility is limited, since going out becomes unattractive to them, and they find themselves somehow “disgusted” with the city because it does not offer them places in which they can flourish. The mere idea of going out may result in emotional discomfort, even before experiencing physical discomfort related to obstacles they may encounter. People with physical disabilities are apprehensive about going out because they know from experience what challenges they will face, and the risk of not having a good time. Beyond pleasure, there is also the notion of the usefulness of an outing.

Accessibility limitations generate limitations to useful activities such as work, shopping, and physical activity, among others. The usefulness of an outing may be diminished by both a paucity of opportunities and an inability to meet their own outing-related goals. Since their desire for urban attractiveness cannot be satisfied, the motivation to go out dissipates, and this results in a sort of self-confinement. Social interactions are also affected. As one participant put it, “Being accompanied by able-bodied people is difficult for me. We don’t share the same pace; we don’t travel the same distances; we can’t move around in the same spaces. During outings, I feel embarrassed about ‘spoiling’ their walk, since there are several spaces I can’t move around in, so I impose those spaces where I feel most comfortable. They always have to wait for me and travel at my pace.”

Accessibility is an essential condition for the mobility of people with disabilities in a city, who navigate regarding the accessibility space, but they would also like to move around according to their desires by going to spaces they appreciate completely autonomously. This autonomy can be achieved through accessibility for all based on the concept of universal design, which supports appropriate planning for all users (Imrie & Hall, 2001; Iwarsson & Ståhl, 2003; Hanson, 2004). The recognition that the users of a city have different abilities and interact with the environment in complex ways is the basis of the universal design strategy. Making spaces accessible without consulting people with disabilities or taking their wishes into account means limiting their movements and controlling them; they will be forced to use accessible paths and will not have the freedom to choose to go where they want.

These shortcomings in the accessibility of the built environment are largely due to public urban planning policies. Actions are carried out in isolation, so that only some building entrances are made accessible, or only some targeted sections of roads are developed rather than thinking about making the built environment accessible via a chain of mobility that creates an obstacle-free path from the home of the person with a disability to their potential destinations. Despite existing regulations designed to benefit people with disabilities (in particular the 2002 law on the protection and promotion of people with disabilities), there is a persistent lack of communication and complementarity between the various services (housing, planning, transport) as well as between local and national actions. The 2002 law is insufficiently clear regarding the actions that should be carried out. In this, it is similar to the PDAU (Master Plan for Development and Urban Planning) of Algiers, which is a guideline of spatial planning and urban management for Algerian cities. Though recommended, public space accessibility is absent from the planning orientations, no details are given to guide its implementation.

Algiers’ geographical and social situation clearly render the task of accessibility difficult, but the adoption of an Accessibility Plan with precise objectives and activities, a corresponding budget, responsible actors, a clear timetable and evaluation and monitoring indicators is indispensable to creating real change. The social inclusion of people with disabilities requires the creation of a city that is accessible and attractive to all. Such an Accessibility Plan must take into account the chain of mobility. This means including spaces for leisure, consumption and sports, work and other necessities, as well as the paths that connect these spaces in a chain of mobility. The aim is to achieve universal accessibility in both directions for all users and all areas of use.

In this study, the space syntax has shown some limitations in terms of predicting the movements of people with disabilities, since it fails to take into account the physical and sensory obstacles at the micro-scale. To overcome this problem, one solution would be to quantify urban accessibility using measurement models deduced from field studies that are specific to people with disabilities, and to link it to syntactic values. Space syntax can enrich thinking about the most desirable spaces for people with disabilities. It offers an idea of which spaces are most attractive, and these are the spaces that are most desirable for people with disabilities. With this study, other perspectives may open up, such as the integration of this relationship between attractiveness and accessibility to concepts of universal design.

The authors address their acknowledgments to research structures, LACOMOFA in Algeria and ESO UMR6590 in France for their material and scientific supports. They also thank the Algerian Ministry of Higher Education and Research, the Palladio Foundation and the Banque Populaire Foundation for funding this research. Finally, they would like to thank Karla Cook for contributing to the review of this paper.