2022 Volume 10 Issue 2 Pages 92-110

2022 Volume 10 Issue 2 Pages 92-110

This work is part of an ongoing research on the impact of urban structure on public squares in Bejaia city (Algeria). This paper will investigate the relationship between the configuration of the urban structure and the use and attractiveness of public squares in Bejaia city. Assuming, from space syntax theory, that urban space configuration extremely effects people’s movement patterns (through-movement space or to-movement space), this study is then carried out to find the correlation between the spatial use of squares and the syntactic properties of the urban structure in which they are embedded. To achieve this goal, the document relies on two approaches: qualitative and quantitative. The qualitative approach is based on the in-situ observation of two public squares by establishing behavioural maps, and on semi-structured interviews. While for the quantitative one, it is based on the method of space syntax concerning the syntactic and isovist properties. The study uses calculations using Depthmap. This paper will present the investigation process and the results of the case study, which show that the use of public squares in Bejaia city depends strongly on the syntactic properties of the urban structure in which each square is embedded, besides its functional properties.

The word “city” is very complex, and it is defined differently from several angles. In urban planning, cities are observed as systems of networks and flows (Batty, 2013). Public squares play a primordial role in urban life and the structuring of urban space. They also participate significantly in the city's image.

Squares and paths combine to form the urban fabric. According to Hillier, B. (1996), this combination is necessary to understand the distribution of movement flows and the system of routes: “Squares are not local things. They are moments in large-scale things called cities”. Urban squares are seen as places of meeting, interaction, relationship and public representation (Cutini, 2003, 2014). Various researches refer to the human co-presence, intensity and disparity of use of public spaces, such as squares, to a multitude of notions: quality of space (planning, comfort, security, etc.), visual accessibility (Montello, 2007; Bada, Yassine, 2012) and spatial network (configuration / space syntax) (Hillier, B. & Hanson, 1984; Hillier, B., 1996).

Space syntax, initiated by Bill Hillier, represents a set of theories and techniques of spatial configuration analysis, overlapped with human behaviour and activities. It considers that the urban structure i.e. the street pattern by its configuration is the main guiding feature of people movement/ flows, and to somehow a certain spatial use of public squares, is at times uneven. The portion of movement that is generated by this configuration is called “natural movement” (Hillier, B. et al., 1993).

The method of analysis of the space syntax and the research in the subject of behaviour and its interaction with the built environment, confirm that the movement of people in space is narrowly related to visual perception. This perception is based on the visual field produced by the configuration of the space in which movement takes place, and changing following the interim of the latter. Thus, space is used and experienced differently by people relevant to spatial cognition. The properties of this configuration can be measured graphically and numerically with one of the available softwares like Depthmap, with different syntactic and isovist values. The located activities and services within the public squares would play a big role too in their use, in that their presence makes these squares more attractive.

Visibility and accessibility are classified among the main characteristics of public space (Carr et al., 1992). Visual access is considered as a decisive factor in the use of this public space, while impacting the readability and understanding of the environment (Montello, 2007; Bada, Yassine, 2016). Visibility (visual dynamics) is linked to the behaviour of the occupants of space and to the physical relationships they maintain with their environment, considered as a natural phenomenon (Turner, 2003). The visual fields generated in relation to these behavioural and experiential properties are called “isovists” (Franz & Wiener, 2005).

The study of open spaces in particular and their use, such as public squares, requires taking into consideration the spatial structure, its components, topography, and every detail that can change the spatial properties in relation to the perceived space (Bada, Yassine & Guney, 2009). The reading of a square in the urban fabric is done on two scales: in relation to the city, because the reading of the square depends essentially on the paths, in both the physical and visual sense; and in relation to its own space, since it depends on how the square is perceived from its interior space. Public squares are a highly complex spatial theme. They involve geometric, architectural, functional, social, historic issues, what makes it actually hard (and also conceptually impracticable) to provide a comprehensive analysis. The purpose of this research is rather to cast a light on the configurational features of public squares, thus observing the matter from a different point of view, trying to integrate it with other aspects. The main question of this work is: Which properties of the urban spatial structure and the public squares impact the use and attractiveness of these squares? To study the impact of urban spatial structure on public squares, the hypothesis of this work is based on the “Space Syntax” theory (Hillier, B. & Hanson, 1984; Hillier, B., 1996), to find a correlation between the spatial use and the syntactic properties of the space.

The case study focuses on two public squares located in two different spatial structures in Bejaia city, which present a range of problems such as the poor quality of space, and the disparities of use and attractiveness. The methodology is based on two approaches: qualitative, based on in-situ observation by establishing behavioural maps, and on semi-structured interviews; and quantitative, based on the spatial syntax method. The syntactic analysis is done using Depthmap, software developed by Alasdair Turner at University College, London (UCL). It is based on two types of analyses, axial and convex; using a set of values, mainly integration. Its measurements take into consideration the two linked dimensions, local and global; the intrinsic physical properties of space and its relational properties in relation to the urban ensemble must be taken into account for the understanding of the use of space. The social reality of the use of space depends on this structure (local, global), and it is extremely defined by this spatial configuration. The axial graphs obtained by this method can perfectly reflect the impact that spatial configuration can have on movement (Hillier, B. & Iida, 2005).

So that users of urban space mark their pauses at the level of the squares, the latter must be configurationally well integrated, offering strategic visual properties, long lines of sight and wide fields of vision (Conroy-Dalton, 2001). Furthermore, these squares must have a position allowing them to connect to the main movement flows, local properties coherent with their functional role, and be characterized by a space unified and defined at its perimeter (Cutini, 2003). The activities around the square and those that it can offer have a multiplier effect on natural movement, thus promoting use and making these urban spaces more attractive (Hillier, B. et al., 1993).

The methodological approach that has been adopted in this work is a mixed approach. It aims to investigate the issue of the impact of the urban spatial structure on public squares, by overlapping a qualitative and a quantitative approach (Figure 1). The qualitative approach based on in-situ investigation aims to analyze on one hand, the behaviour of people within the urban space and the use of squares, through a direct observation and the establishment of behavioural maps; and on the other hand, to assess residents’ experience and perception of urban space and squares through semi-structured interviews. As to the quantitative approach, it is based on syntactic and isovists analyses on a multi-scalar study: on the scale of the entire city of Bejaia, that of the entire study sector including the public squares to study, and finally the local scale of each square. These analyses use Depthmap X, a spatial analysis software.

People’s behaviour in urban space and use of squaresThe observation of the public squares selected for the study was made at the same time and repeatedly for all these squares, for a 10-minute period, five times between morning and afternoon, on weekdays and weekends. The observation is carried out during the spring, when the weather is conducive to exterior activities, and this to avoid the impact of climatic factors, which can completely modify the use of outdoor public spaces while the latter represent the objective of our investigation. The observation considered two types of people: moving people, coming from streets leading to the square; and people engaged in static activities within the square, sitting or standing.

People counting is done by gate-count method for the former, and by static snapshot method for the latter. This allowed us to calculate the number of people coming from each street leading to the square and accessing to the latter (gate counts), as well as the number of those actually using it as a relaxation or meeting space (static snapshots). This last count was done by establishing behavioural maps of the use of these public squares. Thus, we were able to deduce the number of people using the public squares only as crossing spaces. In this study, children accompanied by adults were not taken into consideration, because they are guided to public squares by their companions and not by the spatial structure, and then they do not make any choice at the level of the latter.

Experience and perception of urban space and squares by city residentsThe practice and use of space depend on the perception of the individual, which is determined by the form (Bertrand & Listowski, 1984). Based on this fact, semi-structured interviews were conducted around late morning and early afternoon, on weekdays and weekends, along four days period. Based on Paillé (1991), as cited in Sylvain (2002), the interview is of twelve to thirteen questions, for around a one-hour period. A sample of twelve people was chosen, involving adults and old people of both genders, all of them residents of the city and are acquainted with squares, using them very often, whether they are located on their itineraries for their daily activities or not. The choice of interviewees was also based on a criterion related to level of instruction and knowledge related to the organization of the city. These interviews were conducted at two different scales: at the macro scale with people within the entire study sector, and at a micro scale by interviewing people within each public square. This allowed to better understand on the one hand, how people are guided to public squares from the spatial structure, since natural movement is influenced much more by the global properties of a spatial configuration than by local ones (Hillier, B. et al., 1993); and on the other hand, the way in which they perceive and use these public squares, because each displacement is characterized by two main components of the movement: the itinerary and an easily accessible destination (Hillier, B. & Vaughan, 2007).

The questions were grouped into five themes. The first is related to pedestrian movements within the whole city in order to know the vision of people regarding the liaison of the different parts of the city, and to list the elements that guide them in their movements to a specific location. The second consists of the comparison of pedestrian movements at the level of the old town vs the pericenter (the plain). The third is linked to the relationship between the spatial structure of the city and the use of its public squares, and that in order to know which of the spatial structures retained for the study guides people more easily to public squares. The fourth concerns the personal use reason of the various public squares of the city as well as the elements encouraging people to frequent them. Finally, the fifth theme is linked to the use of the two public squares retained for the study. Information about this last theme are obtained by interviewing on the one hand, people taken within the whole study sector on the attractive characteristics of each of the two squares and on their itineraries to the latter, while classifying them according to their degree of attendance; and on the other hand, those taken within each of the two public squares on their choice of the square, but also on their itinerary until the latter.

Space SyntaxThe analysis made at the scale of the city started by generating the axial map of the whole city (fewest lines map), and then by calculating its intelligibility and synergy values. Intelligibility correlates the connectivity and the integration (HH) values of the axial lines to assess the ease of reading the urban space and the displacement. As for the synergy, correlating the local integration HH (R3) and the global one HH, it informs about the connection of a local structure to the larger structure in which it is embedded. This analysis was made within a radius of 2 and 3 (Rn, R2, R3) since our research focuses on pedestrian movements (Al-Sayed et al., 2014).

A segment map was generated too in order to measure choice and integration, which are characteristic of spatial accessibility and better reveal human movement in the city (Hillier, B. & Iida, 2005). These two measurements were subsequently combined, with the aim of observing the spaces which shorten the distances and which more easily capture the flows (Fouillade-Orsini, 2018b). The radius of this analysis varies between 200 and 800m, that is to say up to 10mn of walking, because the radii exceeding 800m are used for the movement of vehicles (Al-Sayed et al., 2014).

On an intermediate scale, the study sector, which includes only the urban spatial structures to study, was analyzed in order to assess it in relation to its situation within the city, and this by measuring intelligibility and synergy from the axial map (fewest lines map), as well as the choice and integration from the segment axial map, but this time by normalizing these two measures of choice and integration and by combining them. The normalization of choice and integration introduced by Hillier, W., Yang, and Turner (2012) allows the internal structure of the system studied to be highlighted (Fouillade-Orsini, 2018b) and to compare several systems of different sizes in order to assess only the configuration without taking into account the size. Normalized Angular Choice (NACH) allows the spatial structure in the foreground (max value) and in the background (average value) to be understood. As for Normalized Angular Integration (NAIN), it indicates how the foreground and background networks are easily accessible (Fouillade-Orsini, 2018a). This analysis was carried out within a radius varying between 200 and 400m, considering the reduction of the scale of the analysis.

To analyze the object of the study more closely, a third scale is required, and it consists of analyzing each public square within a 200-meter radius of its immediate environment. And in order to conduct this study well, all elements that exceed 1.20m in height at the level of the public square have been represented, since they represent a visual obstruction for the pedestrian. This part consists to calculate first the values of choice, integration and of these two combined measures, and this from the segment axial map. Subsequently, a visibility graph analysis (VGA) which establishes a real correspondence between the configuration and the morphology of public squares was carried out, using the visibility graphs obtained from the axial map. This allowed us to measure the intervisibility between streets leading to public squares and the latter through integration and connectivity measurements. This analysis was made according to a grid of 0.75m and which represents the human scale, since the size of the human step is estimated at 0.75m (Turner, 2003; Pinelo & Turner, 2010; Al-Sayed et al., 2014). In addition to this, isovists with a 360° field of view were generated to simulate the human experience, and this from different points of view located at the end of the streets leading to the public squares, in order to assess the visual access.

Figure 1. Research methodology diagram (Elaborated by authors, 2021)

Bejaia is a Mediterranean city located in the northeast of Algeria, 250 km to the east of the capital Algiers. It is caught between the sea and the mountain and presents itself in an amphitheater following this relief. It is endowed with an urban fabric resulting from a process of stratification and superposition of several layers throughout history. This gave to the city a wealth and diversity in terms of layouts, types of spaces and arrangement of the different elements of the city. In order to study the impact that the spatial structure can have on the use of public squares, the choice of our case study was then focused on this city presenting a particularity, which is the diversity of the types of layouts of the urban spatial structure. This will allow us to answer our hypothesis after comparing the impact of these different layouts on the use of squares.

Choice and presentation of the urban spatial structures to studyThe different historical eras which have followed one another in Bejaia city, each with its own urban facts and its operational concepts, have made Bejaia have several types of urban spatial structures. And in order to investigate our research subject, and for a comparative purpose, two types of urban spatial structures in this city, each integrating some public squares, were chosen according to two criteria: urban continuity and the urban grid form. To know the impact of a given spatial structure on the use of public squares, this structure must be studied in relation to the city, that is to say in a continuous system, because there is a strong relation between the configuration of the spatial structure and the use of public squares at the local level, starting from a global one, following a “spatial hierarchy” (Hillier, B. et al., 1993). For the urban grid form, it tells us about the configuration and the geometry of the urban spatial structure. From these criteria, we opted to study the fabric of the old town, as well as the colonial fabric of the plain.

The fabric of the old town of Bejaia (Figure 2) is located in the northeast, in a continuous system. It is bounded to the north, east, south and southwest by main streets and to the northwest by secondary ones. It is characterized by an irregular geometry of the urban network, as well as a high density of the latter due to the narrow streets and adjoining buildings.

As for the colonial fabric of the plain dating from the French era, it is located to the southwest of the old town (Figure 2), in continuity with the latter and the rest of the city, playing the role of junction between the two parts. It is delimited by main streets on all its sides. And unlike the fabric of the old town, it is characterized by a regular geometry of the urban network, as well as a low density, linked to the density of the buildings, and the good ordering of the latter and the islands thanks to the hierarchy of streets.

Figure 2. Situation of the fabric of the old town and the colonial fabric of the plain in Bejaia city

Source: Direction of Town Planning, Architecture and Construction, Wilaya of Bejaia (DUAC). (Elaborated by authors, 2021)

The choice of two public squares to study in the two different spatial structures mentioned above, was made according to different criteria related to global properties: the situation, the configuration and the connectivity, the geometry of the space (type and number of access), the degree of enclosure, and the presence of activities around the square; and to local properties: the geometrical shape, the size, the walls of the square, as well as the presence of activities inside it. The public square chosen in the fabric of the old town is the square of November 1, 1954. As for the colonial fabric of the plain, we have the square of the martyr Aissaoui. The chosen squares are different in terms of all the criteria, in order to diversify the study and for a comparative purpose.

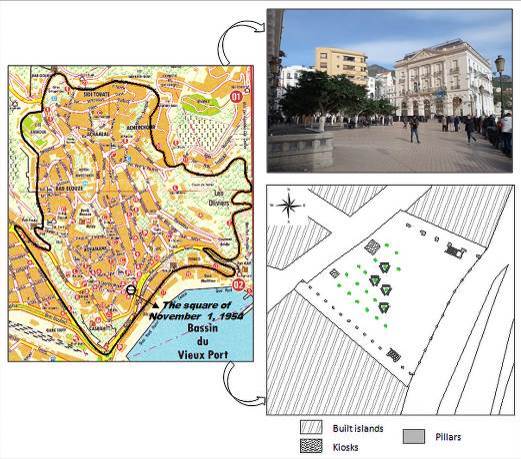

The square of November 1, 1954 (ex Gueydon square)Dating from the French era, Gueydon square, as it was called at that time, was created during the period of the appropriation of the place by the French between 1833 and 1854. It is accessible from three secondary vehicular streets and four pedestrian ones, all of which converge on the only secondary street giving access to the interior of the square along its northwest side. The trapezoidal square is on one level, and it’s quite spacious with dimensions proportional to the height of the surrounding buildings. It is bordered on two sides by colonial buildings (hotel, apartment building and a bank) having double-height galleries with arcades, and it has an urban balcony with panoramic view of the sea and the port throughout its south-east side, and this in view of its creation on an embankment of nearly 20m of vertical drop, recovered by a bridge building housing the city’s cinema. In terms of arrangement, the square contains benches and trees, planted regularly and inscribed in a trapezoid reminiscent of the geometric shape of the square, and it is partly shaded. Its particular characteristic in the city is that it has indoor cafeterias on the southwest side, and the access to the cinema located in the basement.

Figure 3. The square of November 1, 1954 (Elaborated by authors, 2021)

The square of the martyr Aissaoui was created in the French era, after the extramural extension between 1871 and 1891. It is accessible by three main streets and a secondary one. This access is done either directly from the north-west side, or by a staircase of six steps on the south side, and that has seen its creation on a sloping ground.

This small public square, whose usable space is on one level, has an irregular shape defined by the layout of the streets and the urban façade that borders it on the northeast side. This façade is represented by one of the façades of the blood transfusion center, as well as a part of the boundary of a school. It is surrounded by a bar of a small height, and it is equipped with a statue representing the soldier pointing towards the sea, benches, trees, and some green spaces at different levels.

Figure 4. The square of the martyr Aissaoui (Elaborated by authors, 2021)

The results of the in-situ observation show that for the “gate counts” method, the aggregate number of people accessing each square from the different streets and during the entire observation period is 1,764 for November 1, 1954 square, and 148 persons for the martyr Aissaoui square (Table 1). The distribution of this number of people along the axes leading to the squares is shown diagrammatically in Figure 5 and Figure 6. For the “static snapshots” method, the aggregate number of static people present within each square is 1,410 for November 1, 1954 square, and 63 persons for the martyr Aissaoui square (Table 2).

From these results, we note that November 1, 1954 square perfectly ensures its function of meeting place either during weekdays or weekends, and this by accessing it mostly by streets 2 and 4, and it is little poorly used as a crossing space (227 persons on weekdays and 127 on weekends). While for the square of the martyr Aissaoui, it is little used as a meeting space, either on weekdays or on weekends, and it is generally used as a crossing space (55 persons on weekdays and 30 on weekends), and access is via street 3 for most users. These results are in accordance with the expected use since November 1, 1954 square possesses greater geometric and functional properties when compared to the martyr Aissaoui square.

| Squares | Number of people accessing the square | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Weekday | Weekend | Aggregate | |

| November 1, 1954 | 953 | 811 | 1,764 |

| Martyr Aissaoui | 87 | 61 | 148 |

Figure 5. Distribution of the total number of people accessing November 1, 1954 square during the entire observation period along the axes leading to the latter

Figure 6. Distribution of the total number of people accessing the martyr Aissaoui square during the entire observation period along the axes leading to the latter

| Squares | Number of static people within the square | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Weekday | Weekend | Aggregate | |

| November 1, 1954 | 726 | 684 | 1,410 |

| Martyr Aissaoui | 32 | 31 | 63 |

From the analysis of the results of the interviews, we found that the behaviour of people within the urban space as well as the use of squares differ from one person to another, without depending on gender, age or field. The results showed that 75% of people interviewed find that the different parts of the city are linked to each other and that the street network is continuous, with the connection of the different secondary streets to the main axes. As for pedestrian movement within the whole city, eleven people out of twelve find it fluid in terms of navigation; and this thanks to the readability of the paths, which results from the mental image and the presence of landmarks.

By comparing the two spatial structures, half of the interviewees answered that pedestrian movements are made more easily at the level of the old town due to its small size, its urban morphology, the presence of different links and meeting points between its different parts, its diversity and the presence of several landmarks including the notion of neighbourhoods, and finally the familiarity with its places following the fact that it has remained unchanged. While for the other half, it is the colonial fabric of the plain which, according to them, offers the possibility of moving easily in terms of navigation, and this due to its airy spatial structure and its low density fabric, to good visibility resulting from its checkerboard structure, to the diversity of paths to get from one place to another, and finally to its flat relief. Regarding the relationship between the spatial structure and the use of public squares, 58% replied that it is at the level of the old town that people are more easily guided to public squares, and this is related, according to them, to its small size, to the fact that it is designed for pedestrians, to the importance of the squares and their strategic and thoughtful location as at the junction of several routes, and this guidance can be interpreted with reference to the natural movement. The rest of the interviewees consider that certain characteristics of the colonial fabric of the plain make this part of the city orientate moving people more easily toward its public squares compared to the old town; among them, the good visibility linked to the clarity of its spatial structure and its sparse fabric, the diversity and readability of the paths, and finally the location of the squares on important routes.

According to the interviews, the primary function of public squares in Bejaia city is relaxation and meeting. And according to the responses, the criteria that make a public square more used and frequented are the following: a strategic location, the fact of being considered as a landmark, its proximity to centers of interest, its visibility from the spatial structure and the good visibility of its different parts from the interior, its ease of access, the activities present in its surroundings and those that it can offer, its historical and urban value, the characteristics of its walls, its internal characteristics such as the arrangement, the view or panorama it can offer, and finally its openness. The results of the interviews showed that ten people interviewed out of twelve placed the square of November 1, 1954 at the head of the most used urban public meeting spaces in Bejaia city, and all the interviewees access it by street 2, which corresponds to the results of the in-situ observation. While for the square of the martyr Aissaoui, only one person uses it as a meeting space and generally accesses it by the street 2, and a third of the interviewees use it as a crossing space by accessing it by the street 2 always; and these results are not in accordance with those of the in-situ observation, because during the latter, the majority of users of the urban space accessed the square from the street 3.

Space Syntax City scale analysisThe axial analysis (using the fewest lines map) of the entire city of Bejaia has shown that the reading of urban space and the movement within the city are not easily done, and this according to the value of intelligibility, which is lower than 0.5 (0.28). As for the local structure, it is well linked to the global level according to the synergy value, which is above 0.5 (0.61). The results are shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7. Scatter plots showing the intelligibility (a) and synergy (b) measurements

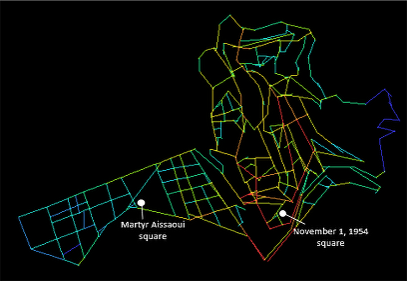

For the segment axial analysis done at the same scale, and from the combination of the two measures of choice and integration to better reveal human movement, we have found that spaces that shorten distances and more easily capture flows are found at the geographic centre of the city (taking into account the localisation and the number of segments in red colour). This effect decreases as it moves towards the periphery. The measures of choice and integration, as well as their combination are shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8. Axial segment maps showing the measures of choice (a), integration (b) and their combination (c) within Bejaia city

On the scale of the two urban spatial structures taken together, we have noticed from the axial analysis that at this level, the reading of urban space and the movement are not easily done, and this according to the value of intelligibility (0.18); and even the local structure is not well linked to the global level according to the synergy value (0.32). The results are shown in Figure 9. For the potential of movement to and through the background network and to the foreground one, deducted from the segment axial analysis and the combination of normalized angular choice and integration (NACH and NAIN respectively), it is much higher in the old town (max value of combined NACH and NAIN = 0.053) compared with the colonial fabric of the plain, with a max value of these two combined measures of 0.025 (Figure 10, Table 3).

Figure 9. Scatter plots showing the intelligibility (a) and synergy (b) measurements

Figure 10. Axial segment maps showing the measures of NACH (a), NAIN (b) and their combination (c) within the study sector

| Urban structure | The fabric of the old town | The colonial fabric of the plain | |||

| Attribute | Minimum | Maximum | Minimum | Maximum | |

| NACH | 0.959 | 1.974 | 1.073 | 1.693 | |

| NAIN | 0.008 | 0.089 | 0.018 | 0.045 | |

| Combined NACH and NAIN | 0.004 | 0.053 | 0.009 | 0.025 | |

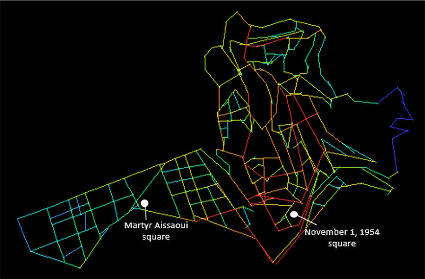

At the local level of each public square, the results of the segment axial analysis show, from the calculation of the values of combined choice and integration (Figure 11, Table 4), that November 1, 1954 square is the one that more easily captures flows, with an average value of 11,530.6, then comes the martyr Aissaoui square with 8,051.53. And from the number of axial segments calculated at the end of each street leading to each public square, and from their average values of combined choice and integration (Table 5), we note that for November 1, 1954 square, it is street 4 that more easily captures the flows with an average value of 12,636.4, then comes the street 1 with 12,152.7. While for the square of the martyr Aissaoui, it is the street 2 that has the greatest potential of movement, with a value of 12,549.6, followed by the street 3 with 10,957. We notice that these results are not in accordance with those of the in-situ observation and the “gate counts” method.

Figure 11. Segment axial maps showing the measure of combined choice and integration around the two public squares and within 200-meter radius perimeter: November 1, 1954 square (a), martyr Aissaoui square (b)

| Name of the square | November 1, 1954 | Martyr Aissaoui |

| Attribute | Minimum Average Maximum | Minimum Average Maximum |

| Combined CH & IN | 18,39.22 11,530.6 16,524.7 | 1,704.87 8,051.53 12,767.1 |

| Name of the square | Streets |

Number of axial segments at the end of each street |

Average values of combined choice and integration of the axial segments |

| November 1, 1954 |

Street 1 Street 2 Street 3 Street 4 |

01 06 03 03 |

12152.7 11751.3 10014.6 12636.4 |

| Martyr Aissaoui |

Street 1 Street 2 Street 3 Street 4 |

02 01 01 05 |

10099.9 12549.6 10957 9378.1 |

From the visibility graph analysis, carried out at the same scale, we note that the martyr Aissaoui square is the most integrated and the most connected visually (Figure 12), with average values of these two measures of 9.342 and of 9,649.47, respectively (Table 6), and which does not reflect its use according to the in-situ observation. Regarding the visual integration and connectivity measures of each street leading to each public square, we note that the street 4 leading to the square of November 1, 1954 is visually the most integrated and the most connected, with respective values of 5.65 and 5,445. While for the square of the martyr Aissaoui, it is the street 3 that is the most visually integrated with a value of 12.11, and for the connectivity, it is the street 4 that comes in first position with a value of 18,148. The results are shown in the Table 7.

(V.In)

(a)

(V.In)

(b)

(V.Con)

(a)

(V.Con)

(b)

Figure 12. Visibility graphs showing the measurements of visual integration (V.In) and connectivity (V.Con) around the two public squares and within 200-meter radius perimeter: November 1, 1954 square (a), martyr Aissaoui square (b)

| Name of the square | November 1, 1954 | Martyr Aissaoui |

|---|---|---|

| Attribute | Minimum Average Maximum | Minimum Average Maximum |

| Visual integration | 2.09955 4.35095 6.74614 | 3.51046 9.34249 16.8355 |

| Visual connectivity | 0 4,147.91 11,135 | 341 9,649.47 26,597 |

| Name of the square | Streets | Visual integration measurement values | Visual connectivity measurement values |

| November 1, 1954 |

Street 1 Street 2 Street 3 Street 4 |

4.80 4.87 4.56 5.65 |

2336 2441 2889 5445 |

| Martyr Aissaoui |

Street 1 Street 2 Street 3 Street 4 |

9.60 8.92 12.11 10.76 |

14815 5245 11969 18148 |

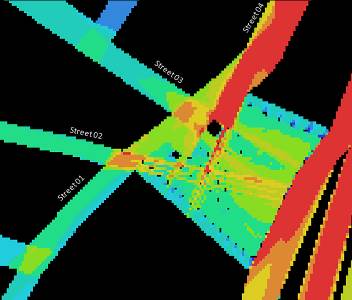

Finally, the results of the isovists (Figure 13, Table 8) are in accordance with the visual properties of the different streets leading to each square. And this, given that the best visual properties (visual integration and connectivity) obtained for one of the streets leading to each public square, are supported by the results of the isovists. The visual field in red colour is recorded for the street giving the best visual access; with the highest isovists’ area values of 2,238.11 for the street 4 leading to the November,1 1954 square, and of 9,770.41 for the street 4 too leading to the martyr Aissaoui square.

Figure 13. Isovists obtained from viewpoints located at the end of the streets leading to the public squares: November 1, 1954 square (a), martyr Aissaoui square (b)

| Name of the square | Streets | Isovists’ area values |

|---|---|---|

| November 1, 1954 |

Street 1 Street 2 Street 3 Street 4 |

1,225.18 1,159.95 1,031.16 2,238.11 |

| Martyr Aissaoui |

Street 1 Street 2 Street 3 Street 4 |

6,155.78 2,463.88 6,303.53 9,770.41 |

By overlapping the results of the in-situ observation, the space syntax analysis and the interview for each public square (Table 9); we note that November 1, 1954 square is used as a meeting space by accessing it mainly from street 2, what is in accordance with the results of the interviews. This can be linked to different syntactic and visual properties, such as the choice and the integration of the square, and the visual integration of the streets leading to it; as well as to some geometric and functional properties such as the degree of enclosure, the size, the importance of its walls and the presence of activities inside and around it; or to the morphology of the urban spatial structure in which this square is located, and which is characterized by an irregular geometry and a high density; and this according to the respondents’ statements. While for the martyr Aissaoui square, it is mainly used as a crossing space, and this by accessing it from street 3 for most users; although according to the results of the interviews, people classified the street 2 as being the most used to reach this square. Despite the fact that the martyr Aissaoui square has good syntactic and visual properties of the square, such as visual integration and connectivity, and of the main streets surrounding it, such as choice, integration, visual integration and visual access, its low degree of use can be linked to geometric and functional properties deduced from the interviewees' statements, such as the low degree of its enclosure, the lack of importance of its walls and the absence of interesting activities inside and around it; or to the characteristics of the spatial structure such as its regular geometry and its low degree of density.

|

Square Methods and measures |

November 1, 1954 | Martyr Aissaoui | |||

| In-situ observation | Gate counts | St.1 St.2 St.3 St.4 | St.1 St.2 St.3 St.4 | ||

| 120 947 191 506 | 26 16 65 41 | ||||

| ∑ = 1,764 persons | ∑ = 148 persons | ||||

| Static snapshots | 1,410 persons | 63 persons | |||

| Space Syntax | Segment axial analysis |

Combined choice and integration |

11,530.6 | 8,051.53 | |

|

St.1 = 12,152.7 St.2 = 11,751.3 St.3 = 10,014.6 St.4 = 12,636.4 |

St.1 = 10,099.9 St.2 = 12,549.6 St.3 = 10,957 St.4 = 9,378.1 |

||||

| Visibility analysis | Visual integration | 4.35 | 9.342 | ||

|

St.1 = 4.80 St.2 = 4.87 St.3 = 4.56 St.4 = 5.65 |

St.1 = 9.60 St.2 = 8.92 St.3 = 12.11 St.4 = 10.76 |

||||

| Visual connectivity | 4147.91 | 9649.47 | |||

|

St.1 = 2336 St.2 = 2441 St.3 = 2889 St.4 = 5445 |

St.1 = 14815 St.2 = 5245 St.3 = 11969 St.4 = 18148 |

||||

| Isovists’ area |

St.1 = 1225.18 St.2 = 1159.95 St.3 = 1031.16 St.4 = 2238.11 |

St.1 = 6155.78 St.2 = 2463.88 St.3 = 6303.53 St.4 = 9770.41 |

|||

(St.: Street)

From the analysis, we deduce that the use and attractiveness of public squares in Bejaia city depend on the one hand, on the distribution of natural movement, which is linked to syntactic properties at a double level: global, due to the configuration of the urban structure of the city or of the larger sector in which is embedded the square, and local, due to the integration of the public square itself (within its limits); or on the visual information obtained at the local scale, such as the visual integration of the streets leading to these squares, i.e. visual access. On the other hand, the morphology of the spatial structure affects the use of squares to the extent that pedestrians tend to use those located in a fairly dense fabric, characterized by the density of different services, and where they can easily find their way by relying on landmarks. They also tend to use the squares located in an irregularly shaped geometric structure, offering several possibilities of moving from one place to another (connectivity/choice) while avoiding long straight routes, and integrating these public squares at the level of the meeting points of different streets and spaces.

Limitations and directions for future researchThe identified limits of this research are on the one hand practical, due to the possible use of cameras or drones for easier and fairer observation of squares’ users, due to privacy laws and regulations; and on the other hand conceptual and computational, since complexity does not allow taking into account the third dimension in the study, which would have given results suitable for better reflecting the perception of urban public spaces and what affects their use. For this, further studies could be carried out in order to take into account this third dimension by relying on models such as 3D informed convex space representation (Cavic, Šileryte, & Beirão, 2017) and versatile data modelling (Sileryte, Cavic, & Beirao, 2017), in order to obtain results that are closer to reality. Therefore, the development of this work would include more public squares of each type of spatial structure, for a more comparative and thorough study.