2022 Volume 10 Issue 3 Pages 84-107

2022 Volume 10 Issue 3 Pages 84-107

The new town movement is an integral part of post-World War II reconstruction that has gradually been adopted worldwide. As one of the most significant fields of urban development practitioners, new towns generated both high enthusiasm and considerable criticism as consequences fell short of ideals over time. Along with the renewed interest in the new town concept, particularly in Asia and Africa, a new round of research has evaluated such initiatives. With increasing urbanisation and diminishing quality of urban life, many developing countries have introduced this policy for decongesting metropolises and stimulating economic growth. Accordingly, new town development has recently attracted urban planners, developers and politicians in emerging economies and appeared as a critical research area in urban studies. Through leading national policies to cope with housing needs and unplanned settlements in Iran, the first generation of new towns returned after the revolution in 1979. Since then, 17 new towns have been developed, which face various challenges, such as a strong dependency on metropolises and a lack of required infrastructure and facilities. Hence, as a new problem instead of a solution, Iranian new town development has been criticised from different aspects, which are systematically analysed in this paper. Analysing the first generation of new towns in Iran and conceptualising the second ones indicate an inevitable necessity for a review and substantial change regarding this policy. Therefore, key recommendations have been formulated and proposed for evolving the first and planning the second generation of new towns in Iran.

The creation of new towns is a unique experience for all planners, both theoretically and practically. It is also one of the most significant fields for policymakers and urban development practitioners worldwide. In the first half of the 20th century, new town development generated high enthusiasm. However, it also received considerable criticism as consequences fell short of ideals over time. In the 1960s and 1970s, some studies reflected on this experience. Moreover, such assessments became more detailed in the 1980s and 1990s. Along with the renewed interest in the idea of new towns, particularly in Asia, a new round of research has evaluated the experience of earlier periods of new town development (Forsyth and Peiser, 2021). Although new towns are arduous to execute and their prevalence has decreased, major new town initiatives and enterprises are increasing worldwide, especially in Asia and Africa, with recent research focusing on their goals, locations and styles (Peiser and Forsyth, 2021).

Since the 20th century, various countries have experienced the large-scale construction of new towns as a significant approach concerning urban development. However, due to their diverse social backgrounds and planning objectives, different countries have used distinct modes in developing new towns (Cai, De Meulder et al., 2020). Several African and Asian countries have started developing contemporary new towns (CNTs) within the last two decades to address urbanisation challenges and simultaneously stimulate economic growth in the Global South. These CNTs are self-contained satellite towns/districts within or on the edge of booming cities, which are usually developed through partnerships between states and international real estate developers for decongesting large cities and stimulating economic growth (Akbar, Abubakar et al., 2020). Many developing countries with increasing urbanisation, growing metropolitan areas and diminishing urban quality of life have adopted the policy of new city development (Alaedini and Yeganeh, 2021; Vongpraseuth, Seong et al., 2020). More governments have introduced this policy to accommodate their growing populations and decentralise their existing metropolises, which have problems stemming from urban functions and existing employment facilities. Accordingly, new town development has recently attracted the urban imaginations of planners, developers, and politicians in the Global South and emerging economies, while also appearing as a critical research area in urban studies, planning, and development (Van Leynseele and Bontje, 2019). Meanwhile, current research has primarily focused on a few iconic cases and neglected other experiences and backgrounds (Cai, De Meulder et al., 2020; Szydlowski, 2021).

Whether in the global experience or in Iran, the concept of new towns was considered a solution for the accelerated urbanisation process at the outset. Apart from rapid urbanisation, this experience in Iran was a means of intervention in the reconstruction period following the Iran–Iraq War (1980–1988). Various studies on new towns in Iran have shown that—despite the legal specification regarding the development of new towns and some valuable achievements—this experience has been criticised due to common issues and challenges. Notably, inappropriate locations, lack of efficient, safe, fast and cheap public transport systems, facility and service shortages, weakness in attracting the target population, and the social segregation and marginalisation of demographic groups are some of the critical issues and challenges surrounding these new towns (Alaedini and Yeganeh, 2021; Arbab, P., 2012; Atash and Beheshtiha, 1998; Azizi and Arbab, 2010, 2012; Basirat, 2019; Faramarzi Asli and Modidi Shemirani, 2012; Hamzenazhad, Mahmoudi et al., 2014; Kheyroddin and Ghaderi, 2020; Majedi, Habib et al., 2015; Shahraki, 2014; Zali, Hatamzadeh et al., 2013; Zamani and Arefi, 2013; Ziari, Keramatollah, 2006; Ziari, K and Gharakhlou, 2009).

In this context, after three decades of planning, the completion of a significant portion of construction projects, and the acceleration of population growth resulting from the Mehr Housing1 Project’s implementation, new towns in Iran represent a significant historical milestone, which requires a rethinking of future perspectives. The officials and managers of developing new towns in Iran (INTDC) insist on this programme’s success and intend to continue developing this policy. On the other hand, scholars and specialists have provided many facts on the ineffectiveness and failure of Iran’s new town policy. This situation highlights the need for a comprehensive evaluation and revision of the performance of Iranian new towns. Such evaluations should include the need to re-invest in new towns in detail and reflect on their positive aspects and past mistakes (Basirat, 2016; Daneshpour, 2005). After reviewing the origins and evolution of new town development globally, the cause and process of new town development in Iran are scrutinised in this study. Through a systematic analysis of the first generation of new towns in Iran, whilst considering planning ideals and realities, the following question emerged: What are the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats facing new town development in Iran? While attempting to answer this question, which indicates the need for a review of new town development, this paper focuses on conceptualising the second generation of new towns in Iran. Accordingly, key recommendations for the future development of new towns in Iran have been formulated and proposed.

Merlin (1980) said that ‘there are a considerable number of planned schemes throughout the world called new towns or new communities’ (p. 77). Indeed, new towns have been created throughout history for many reasons, including security, economic, and demographic concerns. However, after the Industrial Revolution, these settlements were considered differently from the past (Zali, Hatamzadeh et al., 2013). The new town concept is ‘used with the meaning of a straightforwardly emerged town, built on virtually free land, following an established plan, and under expert supervision’ (Panait, 2013).

The origin of the new towns as a significant movement was Howard’s idea named the Garden Cities of Tomorrow, which was presented as a remedy for industrial cities (He, Wu et al., 2020; Iranmanesh and Bigdeli, 2012). This definition was actively and cooperatively implemented in the two new towns of Letchworth (1903) and Welwyn (1919), in England. Accordingly, the new town movement continued on a broad scale and was primarily based on government initiatives (Merlin, 1980). At the inception of the 20th century, the response to urban challenges such as congestion, agglomeration and sprawl in the aftermath of the Second World War was a deliberate decentralisation policy to encourage people to move out of large cities. The demolished city centres were to be rebuilt, with entirely new towns being created as a reaction to what was perceived as problematic (Alexander, 2009; Panait, 2013). Therefore, one of the most significant policies of spatial planning was planning and developing the new towns as a model for population and employment distribution around the large cities, which rapidly spread throughout the world from the second half of the 20th century (Arbab, Parsa and Basirat, 2016; Nakhaei, Rezal et al., 2015). The key objective of this policy was pressure relief from the population in large urban areas (Atash and Beheshtiha, 1998).

Within this context, a new town can be defined as having an exact date of formation, being constructed at a specific time, planned based on the predicted population growth rate, and located in an untouched area without an initial core. Also, these pre-planned settlements can be categorised based on their size, population, and distance. Moreover, new towns can be divided by their particular forms and functions (Majedi, Habib et al., 2015). Keeton and Nijhuis (2019) said that ‘new towns are unique urban developments and heirs to specific and complex planning histories’ (p. 222). They have been characterised as urban fantasies and instant cities that vary in their degrees of public amenities and services and range from bedroom communities to autonomous cities (Keeton and Nijhuis, 2019). The diversity of new towns is due to the era in which they originated and the role that their planners and developers intended to create in the space. On this basis, three main categories of new towns can be characterised during the 20th century (Merlin, 2005):

Table 1 reviews the recent global experiences of new town development in different countries. In developed countries, as the pioneers and originators of this movement, new town development has mostly been stopped or reviewed. Meanwhile, the feasibility of re-utilising this idea in unique patterns are still being considered. In return, many policies to develop new generations of new towns have been continued in some developing countries. In the countries of the Asian region, the Middle East and North Africa, which form the bulk of the experiences, there are a few clear points of interest as follows:

| No. | Country | Important dimensions and highlights | Sources (studies) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | England |

- Stopping the policy of building new towns as the basis of the post-war planning system and welfare state. - Reviewing the policies for developing new towns and proposing to establish new development corporations. - Policy development in the field of locally-led garden cities. - Attention to the regeneration of new towns. |

Alexander, 2009; Dellaria, 2021; DPOBU, 2006; DPMFSS, 2002; Szydlowski, 2021 |

| 2 | France |

- Stopping the construction of new towns and the relative pausing of studies on new towns. - Formation of troubled neighbourhoods in new towns and their improvement programmes. - Adopting a new regional development policy instead of the construction of new towns. - Applying the Paris approach (i.e., extensive and intensive suburban new towns) to form a multi-centre structure in other parts of the world. |

Basirat, 2017a; Gao, Z., Tan et al., 2019; Knox, 2010; Ma and Jin, 2014 |

| 3 | Saudi Arabia |

- Successful experience in the development of new economic cities as part of the macro-economic policy of the country. - Paying attention to the principles of sustainable urban development. - Use of commercial business capacity and the development of logistics and harbour services. - The role of the Saudi government as a facilitator and regulator, whilst budget, land and development are left to private industry. |

Bouhmad, 2016; Keeton, 2011; SAGIA, 2010 |

| 4 | Morocco |

- Continued development of new generations of new towns through financial mechanisms and investment frameworks based on public-private partnerships. - Collaboration with international organisations (European Union institutions and UN-Habitat). - Attention to urban branding and marketing plans. - Investment in non-residential assets and employment opportunities to create attractive, productive and liveable cities. - Paying attention to the principles of eco-cities. |

Radoine and El Mati, 2014; Van Noorloos and Kloosterboer, 2018 |

| 5 | United Arab Emirates |

- The fastest form of new urban development. - Development of Masdar City as a zero-carbon new town in Abu Dhabi. - New urban development in the form of 325 artificial islands. |

Basirat, 2017a; Krane, 2013; Reiche, 2010 |

| 6 | China |

- Targeting residential development as a stimulus for economic growth and subsequent liveability and quality of life. - Diminution of the role of the central government and delegation of authority to local governments and development companies. - Developing new towns as central elements of pro-growth strategies to promote economic growth based on urban entrepreneurialism and competitiveness. - Developing 180 high-speed rail new towns far away from the city centre from 2000 to 2018. - Tianjin and Xiamen eco-cities as low-carbon new town developments. |

Akbar, Abubakar et al., 2020; Arbab, P. and Fassihi, 2021; Arbab, P. and Sedighi, 2021; Chang, Zheng et al., 2022; Dong, Du et al., 2021; Han, Lu et al., 2021; Meisheng, 2004; Song, Stead et al., 2020; Wang, H., Yan et al., 2013; Wang, L., 2020; Xue, Sun et al., 2011; Yu, Lu, Yu et al., 2020; Zhou, 2012 |

| 7 | South Korea |

- Continuity of the policy originates from building massive housing developments in the form of qualitative improvement. - The project of Sejong new town as an administrative capital city and 10 innovative cities to reduce the burden on Seoul. - Development of new towns as complementary facilitators of urban regeneration policy. - Attention to clustering and knowledge-based economic development, especially in innovation cities. |

Arbab, Parsa and Basirat, 2016; Kim, J., Chang et al., 2011; KRIHS, 2012; Kyoung and Kim, 2011; Lee, S., You et al., 2015; Mukoyama, 2011; Vongpraseuth, Seong et al., 2020) |

| 8 | Malaysia |

- Developing new towns to respond to the congesting metropolises whilst also providing rural residents with urban services. - New urban development centred on state-owned economic development companies. - Development of Putrajaya as the new capital of Malaysia with many memorable and festive projects. - Development of Cyberjaya as the new town of all electronics. |

Basirat, 2017a; Ju, Zaki et al., 2011; Lee, L. and Ju, 2014; Omar, 2008 |

| 9 | Kazakhstan |

- Developing satellite towns with well-developed infrastructure and production facilities whilst employing regulating urban agglomerations and sprawling megacities. - Development of the new town of Astana as the new capital city by acquiring a new political and administrative status and investing significant finances. - Acceptance of the terms of international funding institutions that required institutional reforms including public sector reductions and massive privatisation projects. |

Basirat, 2017a; Ghalib, El-Khorazaty et al., 2021; Keeton, 2011; Rykov and Zehong, 2015 |

| 10 | Japan |

- New towns benefit from Japan’s public research and development budget (like Tsukuba New Town). - Evolution of national roles like the concept of Technopole and Japan’s Technopolis Programme. - Developing new towns to provide affordable housing and curb urban sprawl through the use of urbanisation control areas (UPAs) and urbanisation promotion areas (UCAs). - Facing problems such as land ownership fragmentation and a lack of suitable level land. |

Kiuchi and Inouchi, 1976; Mberego and Li, 2017; Rowe, 2021; Tanabe, 1978; Yokohari, Amemiya et al., 2006 |

First, the document study method was used to review the origins and evolution of new town development worldwide. Then, the cause and process of new town development in Iran were reviewed. This section provides the necessary insights concerning the subject’s definitions, backgrounds, positions, values, priorities, interests, attitudes, trends, and sequences (Mahoney, 1997). However, exploring the research position and analysing the study orientation toward the challenge and issue were required. On this basis, a literature review was conducted to determine worthy topics and provide insights into how the scope could be limited (Creswell, 2009). Accordingly, some major databases—including MDPI, Sage, ScienceDirect, Springer, and Taylor & Francis—were explored to find beneficial research focusing on new town development, especially in Iran. Moreover, a chain-referral approach as a rolling snowball was applied and continued to the point where a good range of resources was leveraged to acquire knowledge on new town development in Iran. This strategy, as an accumulating snowball, is especially beneficial for multisource research to recruit a reasonable representative sample and generate a unique type of knowledge. Thus, through a repetitive process, the researcher accessed informants that referred others (Marcus, Weigelt et al., 2017; Noy, 2008; Sedgwick, 2013).

Secondly, to orient and direct the research toward the aforementioned subject by focusing attention on critical issues and challenges of the first generation of new towns in Iran, the systematic analysis of strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats was used as a decision-making tool. This resulted from the need to discover what could be done regarding planning failure based on a situation diagnosis and discrimination of internal activities from external realities. This process of identifying the significant positive and negative factors and then developing and adopting strategies resulted in proper categorisation and fit being systematically possible. Accordingly, a strategic plan—i.e., a collection of all necessary strategic basics of decision-making from different sources—can be devised to achieve the objectives that should be challenging but achievable (Gao, C. Y. and Peng, 2011; Pahl and Richter, 2009; Pickton and Wright, 1998). Therefore, key recommendations and considerations for the future development of new towns in Iran were ultimately formulated and proposed.

In the contemporary meaning or modern style, Iranian new towns were considered contemporaneous with World War II, which coincided with the pre-revolutionary period in Iran. On this basis, three main models of planned cities or complexes can be categorised for the pre-revolutionary phase of new town construction in Iran (Majedi, Habib et al., 2015; Ziari, Keramatollah, 2006):

In the urban policies section of Iran’s First National Spatial Strategy Plan (1977), the need to focus on the notion of a new town as a set of residential units for housing supply was considered for the following reasons (Amirahmadi, 1986; Scetiran Consulting Engineers, 1977):

In the 1970s, Iran experienced rapid population growth, massive population migration to urban areas, and the unplanned expansion of existing cities, which mostly occurred in major cities. This increasing demographic mobility raised the need for housing and disrupted the establishment and organisation of human settlements in the country. Therefore, Iran initiated a new town strategy to decentralise the large cities’ populations and economic activities. Atash and Beheshtiha (1998) stated, ‘Firstly, by preparing long-term master plans, the government attempted to make the existing urban areas absorb part of the surplus urban population. Secondly, using the new town strategy, the government planned to distribute the urban population among several new communities to be built around the existing large cities in the country’ (p. 2). Therefore, based on government approval in 1985, the post-revolutionary phase of new town planning and construction—one of the critical national strategies in urban development—was assigned to the Ministry of Housing and Urban Development (MHUD). Thus, along with the strategies of infill development and sprawl development concerning existing cities, detached development through the creation of new towns was considered the primary urban development strategy in Iran. The theoretical, methodological and global experience was gathered and analysed in the first step. Then, feasibility, location and design studies of more than 30 new towns in different parts of the country—especially around the metropolitan areas—developed, with some operations beginning in the mid-1980s.

Accordingly, the Iran New Town Development Company (INTDC) was established in 1986 and was responsible for the implementation of new town projects in association with the MHUD (Zamani and Arefi, 2013). On this basis, 17 new towns were proposed around large cities, with a distance of 30 km as the average. These settlements, whose development is still ongoing, are known as the first generation of new towns in Iran.2 This policy’s principal objective has been pressure relief from the population in significant urban areas by directing their future population growth and economic activities to new towns as self-contained communities with various employment opportunities. In other words, these new towns must be considered settlements for the overflow population. By 1986, 22% of the 27 million people (55% of the total population) living in urban areas resided in Tehran (the capital), whilst 45% resided in the eight metropolises of Tehran, Isfahan, Mashhad, Tabriz, Ahwaz, Shiraz, Kermanshah and Qom, each with populations of 500,000 or more (Atash and Beheshtiha, 1998).

Upon closer inspection, the planning and development of the 17 aforementioned new towns must be considered in light of the following goals in terms of shaping and directing future urban development (Hamzenazhad, Mahmoudi et al., 2014; Zamani and Arefi, 2013; Ziari, K and Gharakhlou, 2009):

Figure 1 presents the location and spatial distribution of the first generation of new towns in Iran. Table 2 provides their demographic characteristics as well as some planned and achieved indices regarding their population realisation according to the first or subsequent plans. Analysing the population of the first generation of new towns shows the following dimensions:

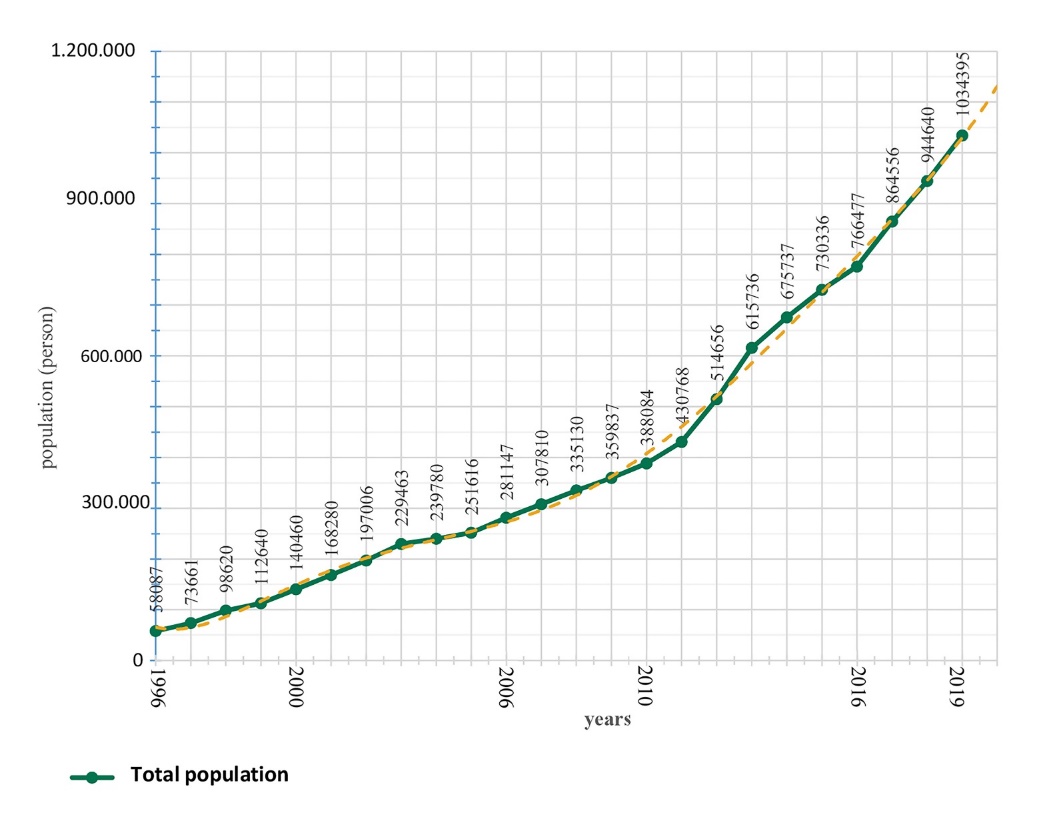

Based on the latest estimate of the INTDC in 2019, Figure 2 presents the population settlement trends of these new towns. Accordingly, the total population living in the first generation of new towns in Iran has exceeded 1 million, which indicates the realisation of approximately 30% of the last population ceiling projected for them.

| No. | New town | Province | Population-2016 | Distance from the mother city (km) |

First approved comprehensive plan (1) |

The population planned in the next plans and additions (2) |

Percentage of population realisation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | year | Population | Year | First master plan | Last master plan | |||||

| 1 | Ansisheh | Tehran | 116,062 | 11 | 103,000 | 2000 | 130,000 | 2011 | 113 | 89 |

| 2 | Pardis | 73,363 | 17 | 150,000 | 1995 | 450,000 | 2011 | 49 | 16 | |

| 3 | Parand | 97,464 | 35 | 80,000 | 1998 | 483,000 | 2013 | 122 | 20 | |

| 4 | Hashtgerd | Alborz | 42,147 | 35 | 130,000 | 1993 | 675,000 | 2010 | 32 | 6 |

| 5 | Baharestan | Isfahan | 79,023 | 15 | 320,000 | 1993 | 320,000 | 1993 | 25 | 25 |

| 6 | Fouladshahr | 88,426 | 25 | 320,000 | 1994 | 320,000 | 2014 | 28 | 28 | |

| 7 | Majlesi | 9,363 | 65 | 140,000 | 1993 | 140,000 | 2013 | 7 | 7 | |

| 8 | Sadra | Fars | 91,863 | 15 | 200,000 | 1995 | 340,000 | 2010 | 46 | 27 |

| 9 | Sahand | East Azerbaijan | 82,494 | 20 | 90,000 | 1998 | 150,000 | 2010 | 92 | 55 |

| 10 | Golbahar | Korasan-e-Razavi | 36,877 | 35 | 200,000 | 1993 | 240,000 | 2015 | 18 | 15 |

| 11 | Binalood | 5,635 | 55 | 113,000 | 2002 | 113,000 | 2002 | 5 | 5 | |

| 12 | Ramshar | Sistan and Baluchestan | 62 | 35 | 60,000 | 2000 | 60,000 | 2000 | 0 | 0 |

| 13 | Aalishahr | Booshehr | 23,178 | 24 | 100,000 | 1986 | 100,000 | 1986 | 23 | 23 |

| 14 | Ramin | Khoozestan | 0 | 38 | 63,000 | 2004 | 63,000 | 2004 | 0 | 0 |

| 15 | Shirinshahr | 0 | 35 | 75,000 | 2004 | 75,000 | 2004 | 0 | 0 | |

| 16 | Mohajeran | Markazi | 20,346 | 28 | 60,000 | 1997 | 100,000 | 1997 | 34 | 20 |

| 17 | Alavi | Hormozgan | 174 | 22 | 100,000 | 2013 | 100,000 | 2013 | 0 | 0 |

| - | Total | 766,477 | - | 2,304,000 | - | 3,859,000 | - | 33 | 20 | |

Source: INTDC, 2017

Notes:

1. Notably, there were no specific horizons in demographic estimates in the set of plans for new towns, and only population capacities were proposed.

2. Including all reviewed plans and housing-related programmes (e.g., Mehr Housing Project) in the new towns.

Source: (INTDC, 2020)

As explained, Iranian new towns in the first generation have mainly been developed to solve housing problems and respond to the rapid pace of population growth. However, many experts believe that in developing countries like Iran, the new town policy has become a problem rather than an effective solution for the government (Basirat, 2019; Hasnat and Hoque, 2016; Shahraki, 2014). New towns have remained ‘very expensive projects to be undertaken by national governments in developing countries’ (Atash and Beheshtiha, 1998). Arbab, Parsa and Basirat (2016); Basirat (2019) and the INTDC (2017) showed that the 10 main obstacles and challenges of the first generation of new town policy in fulfilling goals—or even deviating from the achievement of planned environmental quality—are as follows:

Although Iran’s primary new town strategy recommends that ‘new towns should be balanced and self-contained’ (Atash and Beheshtiha, 1998), after three decades, these new towns remain dependent on their mother cities and suffer from a lack of necessary infrastructure and services (Basirat, 2019). Table 3 presents a systematic analysis of the first generation of new towns in Iran whilst reflecting on their strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats.

| Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|

|

-The existence of an independent law for new town development. -The emphasis of national and regional spatial plans on the creation of new towns. -Capacity building by new town planning and development meeting government policies and plans. -Access to cheaper land and houses compared to metropolises and big cities. -Lower congestion and pollution compared to metropolises and big cities. -Maintenance of natural landscapes and agricultural lands around the cities. -Offering bank loans for the construction and purchase of houses in new towns. -Reaching the demographic threshold in several new towns (100,000 people). -Desirable technical capabilities of the specialised and professional body in response to the developmental needs of new towns. -Proper technical quality of the constructions, facilities, and infrastructure. |

-Social segregation in new towns. -Deficiencies and lack of infrastructure and services when compared to the master plan’s forecasts. -Changes in commuting patterns to metropolises and heavy traffic to or from the mother cities. -Focus on the physical dimensions and ignorance of demographic, economic, social and cultural issues as well as vocational considerations. -Ignorance of a systematic approach to new town planning and development. -Unsustainability in terms of energy and recycling, green architecture, land use and transportation. Inefficient and fragmented urban management system. -Top-down approach to policy decisions in new towns. -The limited employment market in new towns for their residents. -Lack of identity and social unity toward creating active citizenship and social life. Low level of viability and quality of life in new towns. -Poor public and private sector partnership in new town planning and development. |

| Opportunities | Threats |

|

-Lessons from past experiences in planning and developing new towns. -Limitations to the development of existing cities and metropolises. -Investment opportunities in new towns for the private sector. -Opportunity to use vast international experiences in new town development. -The need for new towns as a policy to alleviate the imbalance of the population. -Recreational tourism capacity in the form of resorts in new towns. -Existence of vast construction capacity in different regions of the country. -The legal responsibility and obligation to provide services and facilities in new towns. -Proof of the need for the gradual and step-by-step maturity of new urban developments through a continuous planning process. |

-Lack of effective policies for controlling the hyperdynamic growth of urbanisation in Iran. -Neglect of environmental potential and limitations in the site selection process of new towns. -Lack of an approved and consensual national urban policy. -Contradictions between the new towns and infill development in existing cities. -Profound and rapid changes in urban, housing and land policies. -Fragmentation of the decision-making system. Failure to link to regional/national plans concerning territorial balance, industrial development and employment. -Threats to and destruction of agricultural land and ecologically sensitive areas. -Opaque land sales as the primary source of finance in new towns. -Lack of sufficient knowledge and utilisation of relative regional advantages in new town planning and development. |

Source: based on Alaedini and Yeganeh, 2021; Arbab, Parsa and Basirat, 2016; Atash and Beheshtiha, 1998; Azizi and Arbab, 2010, 2012; Basirat, 2015, 2016, 2017a, 2017b, 2019; Daneshpour, 2005; Faramarzi Asli and Modidi Shemirani, 2012; Hamzenazhad, Mahmoudi et al., 2014; INTDC, 2017, 2021; Iranmanesh and Bigdeli, 2012; Kheyroddin and Ghaderi, 2020; Majedi, Habib et al., 2015; Nakhaei, Rezal et al., 2015; Zali, Hatamzadeh et al., 2013; Zamani and Arefi, 2013

Since the mid-20th century, environmental challenges have become one of the leading global concerns in an urbanising world (De Jong, Joss et al., 2015; Hardoy, Mitlin et al., 2013). Thus, in recent decades, a new and rapidly growing body of literature has emerged about the importance of new terms and approaches such as the sustainable city (Akbar, Abubakar et al., 2020; Basiago, 1996; De Jong, Joss et al., 2015; Satterthwaite, 1997), eco-city (Caprotti, 2014; Flynn, Yu et al., 2016; Joss, 2011; Register, 1987; Roseland, 1997; Zou and Li, 2014), low-carbon city (Kim, K. G., 2018; Peng and Bai, 2018; Tan, Yang et al., 2017; Wang, H., Yan et al., 2013; Yu, Li, 2014) and smart city (Allam and Newman, 2018; Arbab, P. and Fassihi, 2021; Das, 2017; Song, Stead et al., 2020; Trindade, Hinnig et al., 2017; Yigitcanlar, 2015). These approaches reflect efforts to explore the answers to environmental challenges such as climate change, which is the most significant issue of the 21st century in the cities themselves.

Meanwhile, the Middle East region is considered one of the most vulnerable areas to climate change impacts because its water scarcity is the highest globally (Elasha, 2010). Due to its unique geographical and environmental characteristics, Iran is a country that enjoys a wide variety of climatic conditions. Thus, it is the habitat of countless marine and terrestrial species. However, over the past few decades, precipitation shortages, continued drought, severe fluctuations in the available limited water resources and their contamination, air pollution in cities and industrial areas, increased soil erosion and loss of vegetation, and the impacts on biodiversity have imposed an enormous burden on the country’s natural resources (MRUD, 2017). This country is severely vulnerable to climate change, with vast areas of arid and semi-arid lands, fragile mountainous ecosystems and an economy that is heavily dependent on the production, processing and sale of fossil fuels. In recent years, water scarcity has increased due to land use and climate change, particularly in arid or semi-arid areas (Rafiei-Sardooi, Azareh et al., 2022). As such, Iran is facing severe challenges in the water sector. This challenge was caused by mismanagement and the thirst for development, inefficient agriculture, rapid population growth and inappropriate spatial population distribution (Madani, 2014).

Also, Iran’s government should follow Article 50 of the Constitution on the environment, which requires the preservation of the natural environment for future generations. Moreover, Iran should continue to pursue its international environmental commitments such as the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change in 1992, the Kyoto Protocol in 2005, the Paris Agreement on Climate Change in 2016 and the Intended Nationally Determined Contribution in terms of reductions in greenhouse gas emissions. To overcome global and national environmental challenges whilst moving towards a new approach to climate change, it seems that the general ideal type and direction of the second generation of new towns in Iran can be established based on the notion of the green city, according to the following principles (Meijering, Kern et al., 2014; Wang, X., Wang et al., 2017):

On the other hand, the green city trend—complemented by the smart city trend to create a smart green city—paints the picture of a multifunctional place of dwelling, work, recreation and transport with systematic infrastructure through intelligent, integrative and effective energy monitoring (Kim, S. A., Shin et al., 2012). On this basis, the primary orientation that can define a conceptual change and guide the transformation in new town development is Green Eco Smart New Towns. Developing new towns with advanced and sustainable urban concepts establishes new economic development poles and symbolises local economic achievement, higher quality of life, and innovative urban changes (Song, Stead et al., 2020). However, it is essential to ask the following question: Can new towns achieve a higher level of sustainability or is this a fictitious matter for us and policymakers? Chen, Hadjikakou et al. (2018) argued that cities are crucial in leading global climate change mitigation strategies; however, some studies and cases indicate that energy consumption, unhealthy lifestyles, and carbon footprints per capita in the transport sector are higher in the suburbs (Allam and Newman, 2018; Guhathakurta and Williams, 2015; Lenzen, Dey et al., 2004). However, with well-serviced developments and well-planned areas, new towns can help avoid what can be called climate sprawl, scattered new development, climate gentrification and increased housing demand and prices in attractive developed areas (Forsyth and Peiser, 2021).

New Principles for the Second Generation of New TownsMeanwhile, in the current situation, the country’s urban development system faces new national and transnational realities and challenges that make it necessary to rethink the position and role of Iran’s new towns in the national spatial development policy. The following items are noted in this regard:

In such a situation, it is necessary to learn from the experience of three decades of post-revolutionary new towns (i.e., the so-called first generation). This can lead to a review and the formation of a new agenda for Iran’s national development policy to conceptualise the second generation of new towns and propose recommendations for future development. Accordingly, Table 4 explains this agenda through different dimensions of the proposed new principles for the second generation of new towns compared to the main characteristics of the current (first) generation of new cities in Iran.

| Dimensions | Main characteristics of the first generation of new towns | Proposed new principles for the second generation of new towns |

|---|---|---|

| Socioeconomic nature | Affiliation with the mother city economy. | The new town as an economic node and entrepreneur town. |

|

Focusing on low-income and marginalised groups. Social exclusion. Weakness of the identity. |

The diversity of groups based on economic and geographical bases. Social diversity and the gradual formation of identity. |

|

|

Physical, spatial, and environmental characteristics |

Creation of spaces as private goods. Mass production. |

High-quality urban design and architecture. |

| The medium-sized and occasionally enormous scale. | It depends on needs (small to large scale). | |

| Development around metropolises and big cities based on the location of state-owned land. | Based on macro national and regional strategies and decentralisation policies. | |

| Finance and management | Sale of state-owned land. | It relies on the power of the private sector and public-private partnerships. |

| National and regional policies |

Placing the population overflow of big cities in new towns. The decentralisation of metropolises. Assisting in the distribution of population and industry policies. Preventing the destruction of the environment and agricultural lands around cities. Adjusting the price of land and housing. State land owned based on location. |

Answer to various issues of the urban system. Rapid urban rail-based public transportation for new towns. Active intervention in preserving valuable natural and attractive areas. Operational tools for national and regional development programmes. Using the capacity of regional transport corridors. Varied and multi-functional cities. Using private land. |

Analysing the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats facing Iran’s new town development as a vital option to address the current and future realities of urbanisation is very significant. First, the country’s population is approximately 80 million, of which 73% live in urban areas. This rate will reach 87% by 2025, which is greater than the global average (53%). Consequently, urban population growth will transfer the housing demand to cities’ peripheries due to the inability of many people to afford to settle in large cities. This issue results in the creation and expansion of informal and spontaneous settlements. Secondly, according to the Iran Comprehensive Housing Plan (2017–2026), by 2026, the construction of 4.8 million residential units is required in urban areas, with 2.2 million units in renovated urban districts and 2.6 million as new housing (MRUD, 2015). Furthermore, transforming the population structure and lifestyles (e.g., increasing single-person households) can reduce household size and accelerate the country’s total housing demand. Meanwhile, the limitation of cities’ existing capacities and the complexity of infill development raises the need for new urban development.

Moreover, the need to organise the urban system and create new activities on the country’s southern coasts based on regional capacities, developing oil and gas industries, port facilities and business services also boost the need for new town development. This relates to improving the economic and living conditions associated with developing opportunities for access to superior services. It is also related to addressing the country’s growth and liquid capital by establishing planned thematic developments such as tourism, health care, scientific research, sports and other functions. Private sector investment in new towns can balance these increasing new tendencies around the country concerning regional and local potential as well as various economic factors. Accordingly, as one of Iran’s central urban policies, new town development remains a rational and justified solution. Fortunately, there is a desirable context for localising and implementing new approaches, models, methods and technologies in developing new towns in Iran. This situation provides an opportunity to redirect the second generation of new towns in Iran to become green eco smart new towns. However, due to the aforementioned unresolved challenges of the first generation of new towns and the need to evolve and redefine this policy for the following generations, it is necessary to follow distinctive strategies for the future development of new towns in Iran. Therefore, as Table 5 shows, key recommendations for the future development of new towns in Iran have been formulated and proposed in different dimensions and directions.

| Dimensions | Directions | Key recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| National and regional policies | 1-Upgrading the position of new towns in the Iranian urban system. |

1-1-Preparing Iranian new towns’ national development policy as part of the Iran National Urban Policy (NUP). 1-2-Stabilising the country’s long-term spatial development policies. 1-3-Using the capacity of new towns as a second wing to balance the country’s urban system alongside infill development opportunities. 1-4-Directing new town development based on regional potentials and territorial requirements. 1-5-Integrating new town planning into the national housing and economic development policies. |

|

Physical, spatial and environmental characteristics |

2-Development of new smart and environmentally friendly new towns. |

2-1-Applying a low-carbon urban development approach to new towns. 2-2-Designing a specific planning and design framework for new towns. 2-3-Pursuing scientific and innovative approaches for locating, planning and designing new towns. 2-4-Considering the viability and environmental quality of new towns. 2-5-Establishing sustainable transport systems and promoting pedestrian-oriented development. |

| Finance and management | 3-Institutionalising the characteristics of good urban governance and integrated urban management. |

3-1-Establishing a new urban management system for new towns. 3-2-Cutting off financing methods for new town development from the sale of raw land. 3-3-Developing technical and professional interactions at the national and international levels. 3-4-Providing a suitable atmosphere for the creation and expansion of Non-Governmental Organisations and Community-Based Organisations to participate in the management of new town affairs. 3-5-Emphasis on qualitative considerations rather than quantitative goals 3-6-Developing public facilities before the housing construction phase. |

| Socioeconomic nature | 4-Transformation of new towns into self-sufficient, dynamic and inclusive sustainable urban societies. |

4-1-Developing an entrepreneurial new town guide. 4-2-Establishing quality of life and residential satisfaction monitoring systems. 4-3-Bridging social divides. 4-4-Facilitating the gradual formation of identity. 4-5-Expanding cultural infrastructure, public spaces and venues. 4-6-Considering the public arts and urban art manifestations. |

Over the past three decades, the first generation of new towns focused on resettling the surplus population of metropolises. Thus, these towns have mostly become dormitory towns. However, they can still be useful in locating and supplying housing, employment and specialised roles to improve population distribution and activities across the country. Notably, the importance of this issue has been highlighted in the experience of national spatial policymaking in the country from Iran’s First National Spatial Strategy Plan until today. It cannot be forgotten that the implementation of the new town policy in practice—concerning the extent of its actions, the scale of operations and the number of its settlements—was a unique experience and undoubtedly a remarkable achievement in Iran’s planning history, especially when the country suffered from problems such as war, economic sanctions, informal settlements, etc. Moreover, the importance of new towns as an opportunity created as a kind of urban planning laboratory cannot be ignored. Through the Iranian new towns experience, many innovative urban planning and design concepts have been practised for the first time.

However, Iranian urban development policymakers should seek solutions to cope with the challenges of new towns. The financial model of Iranian new towns is based on land sales. Thus, they started without the initial cost of services and infrastructure, which must benefit from modern financing models. Locating and concentrating on state-owned land is a serious issue that requires a solution considering the relevant legal, economic and financial considerations. Moreover, the national political inconsistency in urban development is a severe challenge in the new town development procedure. The national urban policy’s stability can significantly help the success of new towns. As in other global experiences, although the identities of Iranian new towns remain a severe issue, it should not be forgotten that identities are not formed suddenly. This is a time-consuming process, and developers of new towns must vigorously facilitate this identity formation. The provision of public facilities beyond housing production is the most crucial factor in accelerating the process of identification in new towns.

Conceptualization, M.B. and P.A.; methodology, P.A.; software, M.B. and P.A.; investigation, M.B. and P.A.; resources, M.B. and P.A.; data curation, M.B.; writing—original draft preparation, M.B. and P.A.; writing—review and editing, P.A.; supervision, M.B. and P.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of the paper.

The authors are immensely grateful to the editor and anonymous reviewers for their supportive comments and beneficial and constructive remarks.

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

- The Mehr Housing Project has been one of the most prominent government policies in Iran over the last decade. It started in 2007 and aimed to cover part of housing shortage by building approximately 2 million affordable residential units on free state-owned lands.

- In addition to these cities, approximately 10 new towns—including Eshtehard (100 km from Tehran), Salafchegan (50 km from Qom and 250 km from Isfahan) and Aasluyeh (250 km from Bushehr) were planned to provide housing facilities to industrial employees.

- Demographic information from 2016 was used because no new National Population and Housing Census has been conducted since then.