2023 Volume 11 Issue 1 Pages 276-296

2023 Volume 11 Issue 1 Pages 276-296

Industrial development causes the phenomenon of gentrification. However, studies on this topic were relatively rare, especially those giving a case of an enclave-shaped industrial area. Given the rapid industrial development in a suburb of the Semarang Metropolitan Region (SMR), this study aims to observe the phenomenon of industrial development-induced gentrification in the Semarang-Bawen transport corridor, especially in an area near an intercity arterial road and an enclave-shaped area. We used satellite image analysis complemented by visual observation and descriptive analysis of the data from 100 respondents for each location to be compared to each other in this study. The results show that unplanned and rapid industrial development has stimulated suburbanization in the study area. Then, residential and low-intensity commercial gentrification followed. They also show that the gentrification process in both industrial areas was quite similar. However, the area near the arterial road had a slightly higher degree of gentrification, and its residents seemed more likely to welcome migrants. Even though previous studies mentioned that social segregation is the negative impact of gentrification, our case study generally showed that the locals felt comfortable living side by side with the migrants. We suggest that the social harmony between the locals and the migrants could be encouraged by the local stakeholders.

Urbanization in developing countries has been accelerating in the last decades (Un-Habitat, 2016). Population migrations from rural to urban, or from city centers to their rural hinterland, are the most common cause of urbanization (Rimal, Zhang et al., 2017; Şen, Güngör et al., 2018; Tang and Di, 2019; Un-Habitat, 2016; Wei and Ewing, 2018). Furthermore, industrial development is one of the triggers for such migrations (Anzoise, Slanzi et al., 2020). It also brings about considerable changes in land use, population density, and the lifestyle and livelihood of the local residents (Jiang, He et al., 2016; Liu, He et al., 2010; Wijaya, Kurniawati et al., 2018; Yin, Zhao et al., 2020; Zhen, Gao et al., 2017). Within suburban areas, an industrial area can foster the transformation process of “desakota” (a location with mixed urban and rural characteristics), especially along the transportation corridors connecting big cities (McGee, 1991).

Industrial development also causes gentrification, according to which the improved surrounding areas of factories attract migrants from a higher social class (Lin and Xie, 2020). In that case, migrants take the local people’s land ownership for conversion from agriculture to industry, settlement, and other intensive uses (Lin and Xie, 2020; Nelson, Nelson et al., 2014). Besides being marked by a change in the style of housing architecture, gentrification involves the local people’s social, economic, and cultural changes (Hudalah, Winarso et al., 2016; Solana-Solana, 2010).

Previous scholars (Mamonova and Sutherland, 2015; Nelson, Oberg et al., 2010; Qian, He et al., 2013; Zhao, 2019) have observed various issues relating to gentrification in suburban areas. Mamonova and Sutherland (2015) focused on the process of rural gentrification in post-Soviet context. Zhao (2019) observed how the local villagers in China were engaged in gentrification. Having a similar context on rural gentrification, Qian, He et al. (2013) focused on interplays between the aestheticization of rural living and indigenous villagers on rent-seeking behavior fostered rural immigration and gentrification. Another study by Nelson, Oberg et al. (2010) aimed to find the fundamentals of rural gentrification in USA. In the Indonesian case, Hudalah, Winarso et al. (2016) study focused on political processes and strategies for supporting and opposing peri-urban gentrification. Other studies observed the gentrification phenomenon around campuses, known as studentification, in suburban areas (Prayoga, Esariti et al., 2013; Susanti, Soetomo et al., 2016). However, studies on industrial development-induced gentrification in suburban or rural areas were relatively rare.

The case of industrial development-induced gentrification occurs in the Semarang-Bawen road corridor, one of the development corridors in Semarang Metropolitan Region (SMR), Indonesia (Buchori, Sugiri et al., 2015; Buchori, Sugiri et al., 2017; Sejati, Buchori et al., 2019; Wijaya, Kurniawati et al., 2018). The establishment of large factories (most of them are textile industries) in the area was affected by the planning policy of its neighboring city (Semarang), which no longer puts industry as a primary concern (Buchori, Sugiri et al., 2018; Sejati, Buchori et al., 2019). Considering the factories have multiplied in the past decade, the area has attracted many migrant workers (Wijaya, Kurniawati et al., 2018) so it is urbanized and gentrified. However, unlike government-led gentrification in China (He, 2019; Kan, 2020; Zhang, R., Zhang et al., 2017), gentrification in SMR tends to be more sporadic, spontaneous, and unplanned with fewer interventions from the local government.

There are two clusters of factories, one located near an arterial road and another slightly far from the arterial road and surrounded by rural areas. The last cluster seems to be an enclave-shaped area and unique in studies on gentrification (Buchori, Rahmayana et al., 2022). The term enclave in this study was due to its location, not economic perspective, as a physically, administratively, or legally bounded territory based on a big industry like mining (Phelps, Atienza et al., 2015). We hypothesized that both kinds of industrial clusters cause a different level of gentrification in their surrounding areas. Two villages on the west of the arterial road (in Bergas subdistrict) and four villages on the east of the arterial road (in Pringapus subdistrict) are potentially the most gentrified areas (based on the Social Status Index/SSI) and then taken as our study area (Figure 1).

Source: the authors’ elaboration from OpenStreetMap and the data of Central Bureau of Statistics

Given the rapid industrial development in a suburb of SMR, this study aims to observe the phenomenon of industrial development-induced gentrification in the Semarang-Bawen transport corridor, especially in an area near an intercity arterial road and an enclave-shaped area. Land-use changes, housing architecture, the interaction between migrants and local residents, and the occupations of migrants are included in our observation. This study is expected to enrich the literature on gentrification in the suburban areas of developing countries. Moreover, it could give governments or urban/regional planners valuable insights into the impact of unplanned industrial development in the suburbs.

Generally, urbanization is characterized by socioeconomic, cultural, and environmental changes (Wu and Zhang, 2012). These changes include lifestyle, physically built-up area, and the environment, initially characterized as rural to urban (Gu, Wu et al., 2012). Several factors, such as industrialization, modernization, globalization, marketization, and government policies, affect urbanization (Gu, 2019). Urbanization occurs because of the rapid population increase in urban areas (Rukmana and Rudiarto, 2016). One of the crucial causes is the people’s migration from rural to urban areas, urged by the desire to improve their welfare (Buchori, Pangi et al., 2020; Mieszkowski and Mills, 1993; Wu and Zhang, 2012). This situation then impacts various aspects, including land-use change (Yılmaz and Terzi, 2020), economic growth, urban development, social and cultural changes, expansion of built-up lands, changes in the composition of settlements, and government policies related to urbanization (Gu, 2019). In areas around the city, rural areas’ physical nature changes to become more urbanized (Legates and Hudalah, 2014).

Suburbanization occurs due to the people’s migration from the city center to suburban areas (Chen, Hadjikakou et al., 2018; Jain, Siedentop et al., 2013; Sridhar and Narayanan, 2016) caused by overcrowding situations in the city center (Feng, Zhou et al., 2008; Garcia-López, 2010; Sridhar and Narayanan, 2016; Sugiri, Agung and Buchori, 2016; Sugiri, A, Buchori et al., 2015). Another factor accelerating suburbanization is the excessive housing price in city centers that encourage residents to look for a cheaper residential alternative in peripheral areas (Liu, He et al., 2010). Besides, government policies related to relocation, old-city rehabilitation, and satellite towns' development also accelerate suburbanization (Feng, Zhou et al., 2008).

Suburbanization pattern is influenced by physical and nonphysical aspects of a region. Suburbanization is low-density construction land with a polycentric or linear model. It follows a high-density construction land (Garcia-López, 2010). This phenomenon often follows road networks’ structure connecting cities (Adeel, 2010; Aguilar, Adrián Guillermo, 2008). Suburbanization characteristics vary from region to region, depending on the city’s structure, geographical and physical conditions, and local political policies (Aguilar, Adrián Guillermo, 2008; Aguilar, Adrián G, Ward et al., 2003; Mieszkowski and Mills, 1993; Sugiri, Agung and Buchori, 2016; Zhang, L., Yue et al., 2018).

Suburbanization also raises the urban sprawl issue, characterized by the development of low-density settlements in either suburban or peripheral areas of a city (Zeng, Liu et al., 2015) or even in rural areas (Altieri, Cocchi et al., 2014). The sprawl of non-agricultural lands can significantly pressure agricultural production, threaten farmland protection, and provide inefficient land use and land fragmentation that compromise sustainable development (Issiako, Arouna et al., 2021; Tian, Ge et al., 2017).

The existence of industry accompanied by informal housing in suburban areas has been a significant cause of the suburbanization phenomenon since the last decade (Aguilar, Adrián Guillermo, 2008; Firman, 2009; Liu, He et al., 2010; Wang, Y. P., Wang et al., 2009). Lower operational costs, availability of cheaper land, lower labor costs, and ease of licensing by local governments in developing industries trigger it (Wijaya, Kurniawati et al., 2018). In connection with suburbanization, the industry’s existence acts as the pull factor, while the limitation of employment in the worker’s origin is the push factor (Wijaya, Kurniawati et al., 2018).

GentrificationGentrification is often associated with the in-migration of higher social strata populations to displace local people with lower social strata (Gu, 2019; Wang, J. and Lau, 2009; Wyly, 2019). The availability of spatial capital (Rérat and Lees, 2011) and accessibility to public transport facilities (Luckey, Marshall et al., 2018) often trigger gentrification. This phenomenon happens due to the local people’s inability to face the rising property prices to decide to move out (Gu, 2019). On the contrary, migrants with higher financial capacity can deal with this rise. The gentrification pattern results in socioeconomic changes impacting a higher functional value of land (Hudalah, Winarso et al., 2016) or more urbanized land uses (Lin and Xie, 2020).

Some previous studies have examined the problem of gentrification in inner suburbs (Badcock, 2001; Rankin and McLean, 2015), suburban (Collins, 2013; Niedt, 2006), and rural areas (Phillips, 1993; Stockdale, 2010). Non-farmer middle-class people’s movement characterizes rural gentrification into a rural area, displacing residents (Bittner and Sofer, 2013; Phillips, Page et al., 2008). In this case, the migrants live and change the shape of their houses or move together to inhabit a new settlement area and act as professional gentrifiers by developing new cultivation of ready-made local commodities in rural areas (Phillips, Page et al., 2008).

Different gentrification occurs in depopulated rural areas. Generally, this area can provide all forms of housing with various types and prices. This situation makes the migrants comfortable living side by side and does not displace the local residents in the competition for residential lands. This kind of gentrification makes socioeconomic and cultural conditions more heterogeneous (Hines, 2010). In this case, the demand for urban newcomers influences gentrification more than the increase in housing supply (Guimond and Simard, 2010). This demand then results in a significant rise in property prices, affecting the local people’s economic conditions and lifestyles.

Generally, gentrification harms social aspects but is positive on physical and economic aspects (Gu, 2019). The often negative impact is the emergence of differences in social class and culture (Alonso González, 2017; Gu, 2019). Meanwhile, positive impacts include urban renewal and increased prosperity. Local government and housing developers often pay more attention to the positive impacts than the negative ones, so they tend to encourage gentrification (Gu, 2019).

By activities, gentrification can be commercial, residential, or industrial. Although recent studies distinguish them, commercial gentrification often accompanies residential gentrification (Ferm, 2016; Pratt, 2009; Zukin, Trujillo et al., 2009). Commercial gentrification increases local businesses (Pastak, Kindsiko et al., 2019) and the percentage of entrepreneurs in services, not manufacturers (Smith, 1979; Wang, S. W. H., 2011). It changes entrepreneurs to higher social strata (Ernst and Doucet, 2014; Zukin, Trujillo et al., 2009) and changes in types of goods and services (Zukin, Trujillo et al., 2009). Furthermore, Pastak, Kindsiko et al. (2019) conclude that current studies tend to focus on three thoughts, namely (1) residential gentrification involving economic aspects so that residential gentrification and commercial gentrification are considered as two interrelated things; (2) economic development impacted by residential gentrification; and (3) changing type of local business causing commercial displacement.

Industrial gentrification involves speculating land prices, encouraging the industry players to sell their building properties to become settlements or trades. The increase in land or building prices makes the industry players unable to survive in their original locations (Lester and Hartley, 2014). In the Hangzhou East Railway Station case, the increase in land prices due to the fast train station construction resulted in industrial gentrification around the station area (Lin and Xie, 2020). Such stations are location-attractive for tertiary industry types, such as services, finance, and real estate services, to replace the local industries (Al-Rashid, Nadeem et al., 2021; Haynes, 1997).

Industrial gentrification has a negative social impact on industrial workers. Closing or relocating less-competitive local industries will result in unemployment, difficulty finding new jobs, a mismatch between work and competence, and rising commuter costs to their new workplaces (Lin and Xie, 2020). In the long term, this labour problem will result in a resident’s displacement (Curran, 2007).

To measure the gentrification rate can use the parameter of household status (Yonto and Thill, 2020). It is a linear combination of work type and education level variables to generate the Social Status Index (SSI) (Ley, 1986). The shift of SSI over time represents the gentrification level. The higher shift rate than the whole region’s average indicates the occurrence of gentrification (Yonto and Thill, 2020). However, this measurement is more suitable for residential gentrification.

This study used a quantitative approach for data collection and analysis. The applied methods were satellite image analysis accompanied by visual observation and descriptive analysis of a questionnaire survey. Satellite imagery analysis with the help of a Geographic Information System (GIS) was used due to its capability in spatially displaying spatial structure and detailly identifying buildings and other objects in a big-scale map, as those in previous studies (Buchori, Pangi et al., 2020; Buchori and Tanjung, 2013; Sejati, Buchori, Kurniawati et al., 2020; Sejati, Buchori, Rudiarto et al., 2020).

There were two levels of analysis, namely macro and microanalyses. The macro analysis aimed to overview the Semarang Regency’s land use pattern in the context of the SMR corridor. The macro analysis used a land cover map in 2019, developed by applying a supervised classification method to Landsat 8 and Sentinel 2A satellite imageries in QGIS software (https://qgis.org/en/site/). In contrast, the microanalysis observed the characteristics of the gentrification phenomenon in Bergas and Pringapus.

The microanalysis consisted of three stages. The first stage used the SSI method to seek urban or rural villages (kelurahan or desa) having the fastest gentrification process. The indicators were the shift in the percentage of the population with higher education levels and non-agricultural occupations. The result was the list of the urban/rural villages, which was then used to determine the micro-analysis’ study. After that, Google Street View, complemented by visual observation, was used to identify the architectural style and the spatial pattern of developer-based housing. The indicators of gentrified houses were the building shape and architectural style that looked different from traditional houses.

The last stage was the analysis of the gentrification characteristics based on the questionnaire survey. The questionnaire aims to gather the following information. The first is the land use aspect and land price changes, carried out to find the land price changes and whether migrants influence these changes. The second aspect is the interaction between the locals and migrants, carried out to compare their interaction displacement level. Lastly, the economic activities caused by the migrants answered how their existence was after the presence of the migrants among the locals. The sample respondents were the locals living next to migrants’ house(s). We used a random sampling technique to select the sample respondents from two locations: the urban/rural villages in Bergas and Pringapus. According to Slovin's formula (Tejada and Punzalan, 2012):

where n is the sample size, N is the population size, and e is the margin of error, and using e = 10%, the respondents for each location were 100. Therefore, the total number of respondents was 200. We asked the respondents’ opinions about land-use change and their interactions with the migrants in their surrounding areas.

Figure 2 shows the spatial profile of Semarang Regency as the extended areas of SMR, where a primary transportation corridor of Joglosemar passes. Joglosemar is a term for a large metropolitan area connecting three big cities in Central Java province: Jogja (Yogyakarta), Solo (Surakarta), and Semarang. The residential pattern generally follows the road system’s pattern. Non-industrial built-up areas develop along the arterial road connecting Semarang and Yogyakarta/Surakarta. The Ungaran Sub-district (Kecamatan), the regency’s capital, looks more developed than others. However, industrial areas are also abundant in the sub-districts of Bergas and Pringapus, two sub-districts on the southern side of Ungaran, where this study took place.

As a suburban area of the SMR, Figure 2 also shows the sprawl phenomenon, indicated by low-density residential areas spreading across this area. This sprawl emerges to respond to the development of Semarang City, the core of SMR, which extends to its suburban areas.

Source: the authors’ elaboration from Sentinel 2A satellite images

Figure 3 shows the land-use change of the sub-districts passed through by the Joglosemar development corridor during 1997-2019. Industrial activities grew significantly there, indicated by the existence of many factories. They take place around the arterial road and in the enclave-shaped area in Pringapus.

The factories’ development in Pringapus was initially unplanned. In the beginning, several small-scale food factories were established. Then, the PT Ungaran Sari Garment 3 (PTUSG)’s factory was built in 1996. It was the first big-scale factory in Pringapus, next to these food factories. This garment factory extended the first and second ones on the arterial road’s side. Afterwards, some other medium- and large-scale factories (most of them were textile industries) were then built there. Although initially unplanned, the Semarang Regency’s government responded to this situation in 2011 by determining this area as an industrial zone in the Semarang Regency’s Spatial Plan for 2011–2031. Since then, the number of factories has increased.

Source: the authors’ elaboration from Landsat 8 and Sentinel 2A satellite images

Table 1 shows the Social Status Index (SSI) of rural/urban villages based on the education level and occupation type data. However, this study was only able to compare data in 2009 and 2016 due to the scarcity of such data for a village administrative level. The indicators of a gentrifying village were the percentage of the village’s population having tertiary education (diploma- or bachelor’s degrees) and a non-agricultural occupation. In that case, villages with above-average values in such indicators were assumed to have a faster gentrification process than their surroundings. The villages were Bergas Lor and Bergas Kidul in Bergas subdistrict (representing an area near an intercity arterial road); Klepu, Pringsari, Jatirunggo, and Wonoyoso in Pringapus subdistrict (representing an area in an enclave-shaped industrial cluster). Those urban/rural villages were then further examined as the study area for the detailed observation, from where the questionnaire survey respondents were taken.

| Sub-district | Urban/Rural Village | Higher Education Level (%) | Non-Agricultural Occupation (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | 2016 | Δ | 2009 | 2016 | Δ | ||

| Bergas | Munding | 0.13 | 0.91 | 0.78 | 42.92 | 54.96 | 12.04 |

| Pagersari | 0.74 | 1.40 | 0.66 | 66.76 | 83.34 | 16.58 | |

| Gebugan | 0.31 | 1.71 | 1.40 | 58.48 | 73.07 | 14.59 | |

| Wujil | 2.15 | 5.82 | 3.66 | 86.87 | 91.87 | 5.01 | |

| Bergas Lor | 2.83 | 8.85 | 6.02 | 45.80 | 93.05 | 47.25 | |

| Bergas Kidul | 1.00 | 5.64 | 4.64 | 67.11 | 80.53 | 13.43 | |

| Randugunting | 2.60 | 4.72 | 2.12 | 92.84 | 99.09 | 6.24 | |

| Jatijajar | 5.95 | 1.50 | -4.45 | 93.39 | 89.69 | -3.69 | |

| Diwak | 3.38 | 4.45 | 1.07 | 76.02 | 83.43 | 7.41 | |

| Ngempon | 1.03 | 5.38 | 4.34 | 95.10 | 96.03 | 0.93 | |

| Karangjati | 4.08 | 6.80 | 2.72 | 100.00 | 96.82 | -3.18 | |

| Wringin Putih | 0.94 | 2.32 | 1.38 | 85.97 | 88.01 | 2.04 | |

| Gondoriyo | 0.54 | 1.21 | 0.67 | 75.18 | 81.84 | 6.66 | |

| Average | 1.98 | 3.90 | 1.93 | 75.88 | 85.52 | 9.64 | |

| Pringapus | Derekan | 8.36 | 3.30 | -5.06 | 89.29 | 75.47 | -13.83 |

| Klepu | 1.64 | 4.11 | 2.48 | 84.22 | 85.38 | 1.16 | |

| Pringapus | 12.11 | 5.30 | -6.81 | 85.24 | 92.54 | 7.30 | |

| Pringsari | 1.96 | 3.83 | 1.87 | 78.31 | 76.91 | -1.40 | |

| Jatirunggo | 0.61 | 1.17 | 0.56 | 44.98 | 64.12 | 19.14 | |

| Wonoyoso | 0.58 | 2.42 | 1.84 | 22.14 | 74.16 | 52.02 | |

| Wonorejo | 1.06 | 1.28 | 0.22 | 78.33 | 69.65 | -8.68 | |

| Candirejo | 0.47 | 0.92 | 0.44 | 75.29 | 34.06 | -41.23 | |

| Penawangan | 0.41 | 0.52 | 0.11 | 61.29 | 30.03 | -31.25 | |

| Average | 3.02 | 2.54 | -0.48 | 68.79 | 66.92 | -1.86 | |

Source: the authors’ elaboration from the data of Central Bureau of Statistics; each shaded cell represents an above-average change in percentage values

The upgraded or new house with a more modern architectural design than others (Figure 4 and Figure 5) and the appearance of new developer-based housing as small-scale to medium clusters dispersed in the study area physically represented the indication of gentrification. Unlike the local people’s houses, the upgraded houses bought by the migrants from the locals were usually fenced. It was understandable because the local people who were more rural had a higher social interaction, so they tended to avoid a house fence. On the other hand, the more urban migrants tended to fence off their houses for security reasons and reduce disturbances from their neighbors.

Figure 6 represents the result of this identification. It shows that, generally, there were indications of gentrification in those urban/rural villages. The developer-based housing grew more in the rural villages of Pringapus, with a broader area per cluster and a more significant number of units. They occupied agricultural lands, such as moor, rice fields, and dry crops. They scattered in the areas close to the existing kampong, replacing the previously agricultural lands. The single-house gentrification was more visible in Bergas (closer to the primary access (arterial road) and more urbanized) than Pringapus.

Source: observed by the authors in 2020

Source: observed by the authors in 2020

Source: the authors’ elaboration from Google Street View, complemented by visual observation

Furthermore, 200 questionnaires, each 100 for Bergas and Pringapus, were distributed during the survey in 2020. The sample respondents were selected using a random sampling technique and were spatially dispersed, as shown in Figure 7.

Table 2 shows the respondents’ profiles by location, namely Bergas and Pringapus. It revealed that there was no significant difference between the profile of the Bergas dan Pringapus respondents. The male and female respondents were proportionate. Most of them had been living there for more than 30 years. The education level of Bergas’ respondents was higher, particularly at the Senior High School level. However, the respondents with a Diploma or University Graduate in both locations were relatively low (11% for Bergas and 7% for Pringapus).

| Profile | Bergas | Pringapus | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 47% | 48% |

| Female | 53% | 52% | |

| Total | 100% | 100% | |

| Length of stay | 5-10 years | 5% | 2% |

| 11-20 years | 9% | 8% | |

| 21-30 years | 12% | 8% | |

| >30 years | 74% | 82% | |

| Total | 100% | 100% | |

| Education | None | 8% | 12% |

| Elementary School | 20% | 28% | |

| Junior High School | 14% | 33% | |

| Senior High School | 47% | 20% | |

| Diploma/Graduate | 11% | 7% | |

| Total | 100% | 100% | |

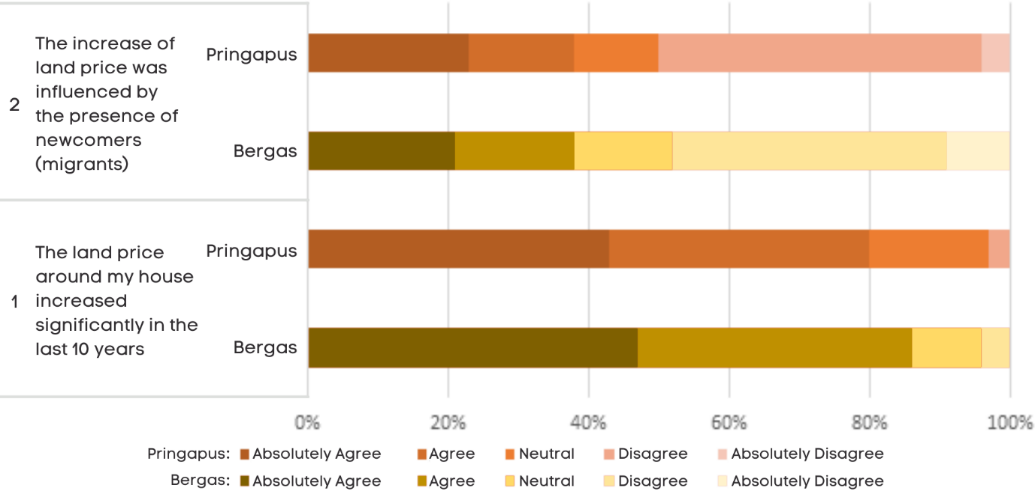

Most respondents in both locations confirmed the increase in land prices around their houses (Figure 8). However, only 38% showed the same results in both locations, though migrants influenced it.

As for the interaction with the local people, most respondents in Bergas (97%) and Pringapus (88%) felt comfortable living side-by-side with the migrants. 94% for Bergas and 80% for Pringapus "agreed" and "absolutely agreed" with the statement that the migrants interacted well with the locals. This different percentage implied that the comfortability of living side by side and the interactions between the migrants and the local people in Bergas were relatively better than those in Pringapus. Similarly, regarding how the migrants displaced the local people, Figure 9 shows higher in Bergas than Pringapus.

About 79% of Bergas and 90% of Pringapus respondents stated that the migrants living next to their houses worked as factory workers. However, the migrant’s types of work in Bergas were slightly more diverse. Although in a small amount, some migrants were working other than factory workers, such as businesspeople/traders (4%), private officers (4%), and civil servants/teachers (6%).

Furthermore, service sector workers tended to increase, as stated by 55% of respondents in Bergas and 41% in Pringapus (Figure 10). This situation was in line with the higher urban level of Bergas compared with Pringapus. However, most respondents agreed that the migrants did not develop businesses related to local agricultural products but tended to run a kind of good and food production.

Regarding the establishment of the developer-based housing that grew in the study area, 45% of respondents in Pringapus stated that some local people living around their houses bought a house in the new housing area. As for Bergas, only 9% of respondents agreed with that statement. This fact was understandable because the new housing location in Pringapus was relatively remote, so the price was also lower. This factor seemed to be one of the reasons why the local people in Pringapus were interested in living in the new housing.

The development of built-up areas driven by the construction of factories in the study area showed the suburbanization process, a common phenomenon in other Java island’s metropolitan regions. Apart from taking advantage of an arterial road, industrial activities in a suburban area could be developed as an industrial estate, such as in Jakarta where industrial estates were based on government policy (Hudalah and Firman, 2012; Hudalah, Viantari et al., 2013). In the case of the SMR, the government developed the industrial estate in the western part of Kendal Regency, not in the southern part where this study took place. However, the industries developed more significantly in the southern part.

A sprawl phenomenon, figured by low-density settlements scattered in the study area, followed the suburbanization process in the southern part of SMR. This phenomenon potentially suppressed agricultural production and endangered farmland protection (Al-Rashid, Nadeem et al., 2021; Sari and Manessa, 2021), marked by many agricultural land conversions into housing and factories. If not anticipated, this phenomenon could threaten environmental sustainability (Tian, Ge et al., 2017).

The built-up areas in the southern part of SMR were driven by establishing the factories along the arterial road. Accessibility seemed to be the primary consideration. However, the industrial activities in Pringapus, an enclave relatively remote from the arterial road, were unsuitable for this consideration. They developed together with the industries along the arterial road.

The majority of industrial activities were labour-intensive and attracted industrial workers as either commuters or migrants. Some of them lived mingling with the local people by buying or renting the local people’s houses. Some others lived in the new developer-based housing spreading over several locations. The housing was available in a small number of units. In this case, as Feng, Zhou et al. (2008) conveyed, a kind of villa or other affordable housing was not present in the study area. The developer-based housing was in the form of a simple house with about 36 square meters or less. The migrants dominantly inhabited these houses, although, in Pringapus, the local people also occupied a few.

Meanwhile, the migrants who bought their houses from the local people usually changed their shape and architecture. These houses then architecturally looked different from their surroundings. They were easily recognizable because they were usually fenced, representing their occupants’ more urbanized and individualist characteristics. To some extent, their existence has accelerated the suburbanization process and triggered gentrification.

Gentrification in the study area differed from that of Hines (2010), in which the migrants did not replace the local people. This kind of gentrification had less possibility of social conflicts between the migrants and the local people. As for the study area, although some migrants in Bergas and Pringapus have replaced the local people, they still could live side by side. Most migrants interacted well with the locals to make them feel comfortable living closely with each other.

According to the local people’s opinion, gentrification was not the only factor causing the significant increase in land prices in the study area. Expansion of industrial activities, especially the establishment of new factories, construction of new housing around those factories, and construction of the Semarang-Surakarta toll road in the last five years, also influenced it. However, the interrelations among those factors caused a significant land price increase. This situation occurred in both Bergas and Pringapus.

The perpetrator of gentrification in the study area was archetypal gentrifiers, a householder who bought one unit of property and then renovated it (Phillips, Page et al., 2008). Professional gentrifiers as the migrants developing ready-made rural commodities (Phillips, Page et al., 2008) in Bergas and Pringapus did not exist.

The spatial capital, usually measured by convenience and proximity to the city center, transportation infrastructure, and trade-services centers (Rérat and Lees, 2011), made the gentrification in Bergas more intensive than in Pringapus. As Rérat and Lees (2011) state, spatial capital has an essential effect on gentrification. It means that the larger the spatial capital, the higher the level of gentrification.

In line with Gu’s opinion (Gu, 2019), gentrification in the study area negatively impacted social aspects but positively on the physical aspects. Residential segregation was a negative social impact, indicated by the separation of the developer-based housing from the kampung settlements. Meanwhile, the physical improvements of the settlements represented the positive impacts on the physical aspects. In this case, the developers have indirectly supported the process of gentrification by providing housing property for the migrants who would like to live close to the factories.

An increase in service workers indicates commercial gentrification (Wang, S. W. H., 2011). This indication appeared in the study area. In line with the concept of Pastak, Kindsiko et al. (2019), the case of Bergas and Pringapus was originally residential gentrification caused by such economic reasons. Then, it triggered the occurrence of commercial gentrification in a low intensity around the residential areas. However, the commercial displacement from traditional businesses such as grocery stores and vehicle repair shops to new businesses like cafes and boutiques (Pastak, Kindsiko et al., 2019) has not yet appeared. Likewise, industrial gentrification, in which higher-skill or higher-wage industries (Tian, Ge et al., 2017) or settlements and trades (Lester and Hartley, 2014) replace industries, has also not yet happened.

In many ways, the gentrification process in Bergas and Pringapus was generally quite similar. The industrial area in Bergas seemed to have a slightly higher degree of gentrification due to its more significant spatial capital. Previous studies mentioned that social segregation is one of the negative impacts of gentrification (Alonso González, 2017; Gu, 2019). Out of the ordinary cases, our case study showed that the locals felt comfortable living side by side with the migrants. Bergas residents with a higher average level of education and greater familiarity with urban culture seemed to have a higher possibility of welcoming the migrants. This phenomenon is similar to the gentrification in southwest China (Zhao, 2019), where the locals and the migrants established mutually beneficial relationships.

Gentrification in the suburban areas of SMR, particularly the Semarang-Bawen transport corridor, was caused by unplanned and rapid industrial development. The construction of factories (most of them are textile industries) has driven the sprawl development of residential areas. Furthermore, it stimulated the suburbanization process of SMR, followed by residential gentrification.

Residential gentrification was indicated by the migrants who, most of them, moved to new developer-based housing or bought and renovated local residents’ houses. In that case, property developers also significantly accelerated the gentrification process by selling houses to the migrants, especially in an area with lower land prices. After that, it was also followed by low-intensity commercial gentrification. This study suggests that gentrification could boost the economic activities in the surroundings of factories. However, governments or urban/regional planners need to anticipate the threat of an unsustainable environment due to massive and uncontrolled land conversion from agricultural to built-up areas.

Taking an industrial cluster near an intercity arterial road in Bergas subdistrict and an enclave-shaped industrial cluster in Pringapus subdistrict as a case study, we observed that both locations had quite a similar gentrification process. The industrial area in Bergas seemed to have a slightly higher degree of gentrification due to its more significant spatial capital (e.g., nearer distance to urban centers and more accessible access to transport infrastructure).

Finally, regarding the fact that the locals felt comfortable living side by side with the migrants, the local government can take advantage of this situation when developing regional development policies applied in the region. In addition, local stakeholders could encourage it to maintain a conducive relationship between the locals and the migrants.

Conceptualization, A.S., E.D.G. and G.F.; methodology, A.S., E.D.G. and G.F.; software, A.S. and G.F.; investigation, A.S.; resources, G.F.; data curation, A.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S., E.D.G. and G.F.; writing—review and editing, A.S., E.D.G., S.A. and G.F.; supervision, E.D.G. and G.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of the paper.

The authors would like to thank the Ministry of Research and Technology/National Agency for Research and Innovation Encourage for funding this study. We also would like to thank Ms. Desita Fatima Azziz and Ms. Puspita Dhian Nusa for their help in data compilation and analysis. Any flaw or weakness is the responsibility of the authors.

This article is a result of the second-year research, part of a multi-year study funded by the Directorate of Research and Public Services, Deputy for Strengthening Research and Development, Ministry of Research and Technology/National Agency for Research and Innovation Encourage, in the scheme of Basic Research for 2019–2021 (257-33/UN7.6.1/PP/2020).