2023 Volume 11 Issue 1 Pages 141-157

2023 Volume 11 Issue 1 Pages 141-157

The world over, increasing automobile trips and the resulting negative consequences, such as traffic congestion, air pollution, and accidents, have been a matter of concern. As a strategy to contain automobile travel by shifting to Transit, a concept called Transit Oriented Development (TOD) has been propagated. This study compares two areas in the city of Naples, Italy, which can be considered a valuable case study. Beginning with the 1997 Transport Plan, the city of Naples has developed a strategy similar to the TOD concept with rail Transit. This study makes a comparative analysis of two urban districts with different urban forms in meeting the characteristics of the TOD concept: 1) the Centro Direzionale, alias central business district, located at the edge of the city centre, and 2) the Municipio area, in the central core of the city. Although different in terms of urban morphology and historical value, these two areas are characterised by high density, mixed land use, and good accessibility to rail transport. The analysis is based on a comprehensive data collection and a comprehensive user response survey, to investigate respectively the features of the analysed districts and travel characteristics of residents and workers. The study analyses socio-economic characteristics along with travel patterns of both areas, to develop meaningful insights regarding the kind of urban form and its level of achieving the benefits of the TOD concept. The paper will conclude with a set of recommendations, on whether to implement high-rise cost-intensive projects in the name of TOD or to preserve the conservative urban form having a glorious urban heritage.

All over the world, increasing automobile travel has been a matter of concern; thus, as a strategy to contain automobile trips, the concept of Transit Oriented Development (TOD) has been propagated by planners and it is being advocated for better land use and transport integration. Even though there does not exist a univocal definition of TOD, it can be said that its main goal is the integration between public transport and urban settlements (Knowles, 2012). Travel demand is influenced by the built environment (Cervero, 1984) along three basic dimensions, viz: density, diversity, and design. The concept of density is meant as household and population density, whereas diversity reflects land use and societal diversity. Design in TOD primarily relates to street and urban design, keeping walking along with other active transport modes like cycling, etc. in focus.

Medium or high urban density values are needed to provide a sufficient number of passengers, able to sustain a high-frequency public transport service, like the tram, train, or metro (Suzuki, Cervero et al., 2013). Mixed land use is expected to shorten distances between origin and destination of trips, also encouraging public transport as the preferred mode choice. Transit share is higher in mixed land use scenarios (Cervero, 1984); similarly, mixed land use and density have a significant impact on travel by single occupancy vehicles (Frank and Pivo, 1994), public transport, and active modes of transport. Mode choice depends primarily on the socio-economic characteristics (Ewing and Cervero, 2001); hence, the diversity component in TOD becomes a crucial and diverse social profile of a TOD zone and will result in greater public transport use. The concept of TOD can be enriched by adding more dimensions (Ewing and Cervero, 2010), from density, diversity, and design (3D) to 5D by including destination accessibility and distance to transit and further to 7D including demand management and demographics. However, our study has limited the analysis to the basic dimensions i.e., density, diversity and design due to the scarcity of reliable data.

In the last years, several pieces of research about TOD have been carried out, especially in North American cities (van Lierop, Maat et al., 2017); other scholars discuss the transferability of the TOD concept (Thomas, Pojani et al., 2018), while some authors reflect on how TOD concept could influence the future of urban and metropolitan planning (Knowles, Ferbrache et al., 2020). A comprehensive review has been made among the vast landscape of studies (Ibraeva, de Almeida Correia et al., 2020) about TOD, some researches are cited here since they represent useful case studies in the light of the goals of this research. A study made for the city of Portland, the most populous city of Oregon, USA, showed that the areas served by high-quality public transport with a good degree of land use mix result in higher public transport ridership with lower rates of car usage, the number of cars per household, and vehicle miles travelled or VMT (Portland Bureau of Transportation, 2009). Research, which referred to the Chicago region, has pointed out that households living in public transport-oriented neighborhoods produce 43% fewer greenhouse gases (Haas, Miknaitis et al., 2010) and policies encouraging public transport-oriented development led to a reduction in emission of greenhouse gases by 36% across the entire region. This study has documented the effects of public transport-oriented development using life cycle assessment approach (Kimball, Chester et al., 2013). This study also analyses the urban redevelopment program carried out by the city of Phoenix, in the USA, where the administrative board has decided to develop the areas close to suburban railway stops. The results show that the city of Phoenix, through the building of 200,000 residential units in stations catchment areas, can contribute by 7% to the objective of Arizona's overall greenhouse gas reduction.

The aforementioned studies highlight some of the most significant effects of land use mix on trip length and choice of public and active transport as travel mode. In general, there have been a variety of studies showcasing the effect of land use, diversity, and socio-economic characteristics on mode choice and travel demand. This study tries to face the research problem linked to the implementation of the TOD concept to reality, in particular applying some of its features to existing cities. Furthermore, it tries to point out the relations between some dimensions of TOD, e.g., density, diversity, and travel choice. Our study is also aimed at contributing to this branch in assessing the TOD applications, by comparing two areas within the city of Naples, Italy. This paper is structured as follows: section 2 contains the literature review, section 3 introduces the methodology and case, section 4 shows the results of the investigation, section 5 does discussions on the study analysis, and section 6 concludes study with its limitations and directions for future research.

Transit Oriented Development (TOD), through higher density, land use diversity, and activity-oriented design, aims to reduce automobile usage and augment public transport ridership along with the usage of active modes of transport. According to the literature, the benefits of TOD also include reducing traffic speed and enhancing pedestrian access to transit stops or stations. Present land use policies have made walking less feasible, less convenient, and more dangerous (Pucher and Dijkstra, 2000); therefore, while planning TOD, planners should consider pedestrian needs and walkability design. Walking should be emphasised as both an indicator and a means of improving the public social realm as part of the improvement in the local environment and urban renaissance (Gehl and Gemzoe, 2003); the cited research also confirmed that for a favorable walking environment it is necessary to promote walking and socially interactive neighborhood.

The prolific literature produced on TOD has identified 3Ds viz. density, diversity, and design as the essential requirements of TOD; furthermore, the literature search attempted to understand how these three variables affect the overall TOD concept. As per several studies, density which refers to population, housing, and employment densities - is negatively associated with trip length, duration of trips, and personal vehicle use (McIntosh, Trubka et al., 2014). Higher density tends to shorten travel and enables favorable conditions for walking, cycling, and public transport (Cervero, 1996; Schwanen, Dieleman et al., 2004; Zhang, 2004). In addition, parking availability and its cost are also significant factors in using personal vehicles (Levinson and Kumar, 1997) and limited parking in dense urban areas discourage car usage (Shiftan and Barlach, 2002). The cited studies have demonstrated that parking policy and pricing can play a relevant role in containing car-based travel demand; thus, the implementation of a TOD policy without a restrictive parking policy may translate into an automobile-oriented development. Again, the selected case study could represent an interesting testing ground for the above-mentioned tenets, considering their similarity in terms of density, and their deep diversity in terms of parking provision.

The studies about land use and social diversity have explored the impact of diversity and mixed-use growth on travel demand (Cervero, 1996; Cervero and Duncan, 2003; Frank and Pivo, 1994). The studies considered relationships at a neighborhood scale and scrutinized the recent claims regarding mixed-use benefits, while few considered jobs-housing balance at a regional scale. The results of such studies show that diversified land use and jobs-housing balance can reduce travel demand and encourage a non-motorized mode of travel: design studies have found that less parking space, continuous sidewalks, grid-like street patterns, increased network connectivity, traditional neighborhood design, transit-oriented, and pedestrian and cyclist friendly development generally encourage walking, biking, and taking public transport (Cervero and Kockelman, 1997; Zhang, 2004). However, it has also been advised that increasing urban density along main roads would improve the likelihood of commuting by private car (Zhao, 2013) and public transport. Some studies explore the socioeconomic aspects of transit-oriented development (Pendall, Gainsborough et al., 2012) focussing on equity; whereas several studies points attention to social sustainability (Fernandez Milan, 2016); Sustainability aspects have been documented in their entirety towards relation with transit development (Kheyroddin, Taghvaee et al., 2014) and urban quality (Knowles and Ferbrache, 2019). Also, significant influence of transit-oriented development on mobility attitude has been observed in the recent years (Jen and Huang, 2013; Pongprasert, 2020).

As the literature review showed, the aspects for benchmarking an urban form as “transit-oriented” and “sustainable” involve several factors, such as travel demand, modal split, walkability, social inclusion, the density of population and employment, etc. However, within the current literature, studies aimed at the implementation of the TOD concept in existing urban areas seem to be quite rare. In addition, studies focused on the assessment of existing urban districts based on TOD characteristics seem to be scarce. This study tries to bridge the cited literature gaps by comparing the identified areas, based upon multiple parameters like socioeconomic characteristics, land use distribution, mode choice, travel demand, etc.

The city of Naples, with 950,000 inhabitants (3,100,000 in the Metropolitan City) is the third most populous Italian city, following Rome and Milan; however, considering population density, Naples (8170 inhabitants/square km) has a higher density in comparison to Milan (7580 inhabitants/square km) and Rome (2220 inhabitants/square km). Naples was the first city, within the Italian peninsula, to be connected to the national rail network - with the construction of the Napoli-Portici railway in 1839 - and the first Italian city served by a “metro” line, due to the opening in 1925 of the railway bypass, corresponding to the current line 2. Over decades, several metro lines have been built or planned, providing good equipment for rail infrastructures, but without a general framework able to integrate and coordinate them.

The Naples Transport Plan, ratified in 1997, building upon a consistent "rail legacy" of past decades, aims at harmonizing existing and planned lines into a general, coherent, network. The plan proposes the improvement of existing urban rails, the building of new metro lines, new stations, new interchange nodes, and park-and-ride facilities, deserving the nickname of "100-stations plan" (Cascetta, 2005). The land use-transport integrated approach, used as a guideline by the Naples Transport Plan, has been later extended to the entire Campania Region, with the definition of the Regional Metro System (Cascetta and Pagliara, 2008). To date, however, the plan is only partially completed. Considering the aforementioned characteristics in terms of population density and availability of rail infrastructure, Naples offers an interesting case study. In this research, two areas have been considered: 1) the Centro Direzionale, and 2) Municipio Square, as shown in Figure 1. The two studied areas - Centro Direzionale and Municipio - are similar in accessibility level, total area, and density, but different in land use and social diversity, urban structure, parking provision, etc. This research aims to inspect the influence of urban form on travel behaviour and find the most relevant factors that encourage sustainable travel modes.

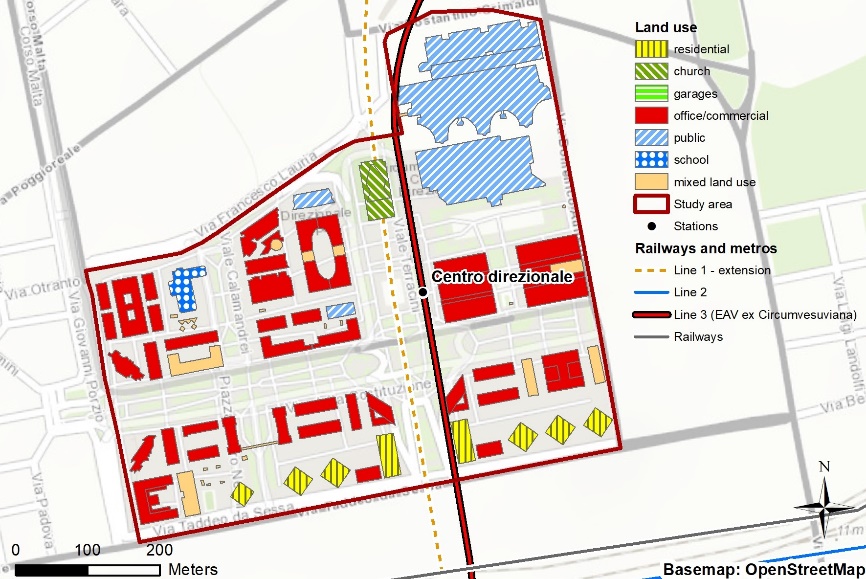

The Centro Direzionale, shown in Figure 2, is a high-rise development close to the Central Station with main offices, services, and tertiary functions, while residential towers are placed in a limited area sector. This district has been mentioned as a sustainable model of development in various research studies including (Canfora and Corbisiero, 2014), which termed it a model of the smart city. Centro Direzionale, made up of office towers, some of which are partially empty due to the real estate crisis, shows remarkable design issues, due to the lack of functional diversity. Actually – despite the abundant provision of walkable spaces – walking into the district can be unsafe, especially in the evening and night, when offices are closed and streets look deserted.

Source: Wikimedia Commons. License Creative Commons (CC BY 4.0)

Centro Direzionale is linked to the former “Circumvesuviana" rail network – today managed by EAV, which connects Naples to suburban municipalities in the northeast sector of the metropolitan area, with a ride frequency of around 20 minutes. The area will be also served by line 1, which is under construction, providing a direct connection to the city centre and the airport. The western sectors of Centro Direzionale are not far from the Central Station (about one kilometer). The Municipio Square, which is named after the presence of the town hall, is characterised by a historic 18th and 19th-century urban fabric with few recent buildings. This area hosts offices and services, integrated with several commercial activities and residences.

Also, regarding land use and social diversity, the selected case study showed remarkable differences: on one hand the business district of Centro Direzionale, and on the other hand the socially and functionally variegated district of Municipio. According to the Naples Transport Plan, the Municipio area will be one of the most important "rail hubs" of the city. The Municipio metro station, which opened in 2015, is currently served by line 1 and will allow interchange with line 6, to date under construction. Line 1 represents the backbone of the metro network of Naples, linking the Central Station, the city centre, and populous residential districts like Vomero, Rione Alto, etc. Despite its central role, line 1, due to limited provision of rolling stock, has a ride frequency of only around 10 minutes during peak hours; thus, unable to meet the travel demand and resulting in overcrowded and delayed rides. Both line 1 and “Circumvesuviana” are occasionally subjected to service disruptions. As per discussions with residents, Centro Direzionale is not considered to be a desirable urban model; hence, it becomes important to study this area in comparison to a conventional city centre, i.e., the Municipio area. The comparative study of these two areas shall be done based on principles of TOD, including the aforementioned aspects of density, diversity, and design.

The Socio-economic Characteristics by AreaConsidering similarities and differences between the two selected areas, the comparative analysis was conducted in terms of travel characteristics of the residents, urban structure, residential density, land use, etc. The two areas are characterised by medium or high urban density, the widespread presence of non-residential functions (tertiary and commercial), and good accessibility to public transport. On the other hand, they show remarkable differences: Centro Direzionale is mainly a tertiary district, characterized by skyscrapers, with dedicated motorway exits. The entire district is built on a "plate", in which the underground level is occupied by car parking, and the ground level is car-free and intended for pedestrians. Whereas, the Municipio area is a historic district within the city centre that has attracted several firms and offices over time, and car parking is quite rare and expensive, in comparison to Centro Direzionale. A comprehensive data collection was done for the study: the data on socio-economic characteristics of the residents in the areas was obtained from the 2011 National Census. The two areas were delimited by using GIS software and information about the prevailing use of buildings was taken from OpenStreetMap©; later that information was verified and amended through physical verification and site appraisal. Table 1 shows the socio-economic characteristics gathered from the 2011 census data for the two areas under study.

| STUDY LOCATION | Centro Direzionale | Municipio |

|---|---|---|

| Area (Ha) | 33.5 | 32.7 |

| Demography: | ||

| Population (N.) | 2482 | 2788 |

| Population Density (Population/Ha) | 74 | 85 |

| Education: | ||

| Graduate and above (N.) | 482 | 764 |

| Primary to Intermediate (N.) | 1895 | 1862 |

| Unschooled (N.) | 5 | 27 |

| Employment*: | ||

| Workers (N.) | 362 | 484 |

| Workforce Participation (Ratio) | 0.15 | 0.17 |

| Travel Demand**: | ||

| Commuting within a municipality (N.) | 1143 | 1105 |

| Commuting outside municipality (N.) | 126 | 87 |

| Commuting within a municipality (%) | 90 | 93 |

| Commuting outside municipality (%) | 10 | 7 |

| Household Character: | ||

| Used residence (N.) | 947 | 1245 |

| Empty residence (N.) | 3 | 15 |

| Total HH (N.) | 950 | 1260 |

| HH Density (DU/Ha) | 28.4 | 38.5 |

Notes: N. = absolute numbers; HH= Households; DU=Dwelling Units

*The Italian Census only detects "Residents older than 15 with work/capital income", and thus is not able to recognize workers with temporary and/or atypical job contracts.

**The Italian Census only detects “commuting trips for education and work purposes”.

Even though Centro Direzionale adopted high-rise towers, the population density achieved (74 per/Ha) was lower than the population density of the Municipio area (85 per/Ha), due to the clear prevalence of tertiary buildings. The household density of Centro Direzionale (28.4 HH/Ha) is also observed to be lower than Municipio (38.5 HH/Ha). The study found that only 7% of people go outside the municipality of Naples for work and other daily needs, whereas 10% of the residents in Centro Direzionale had to travel out of municipal borders.

Land use distributionAfter delimitating the study areas with the help of GIS software, an analysis was made to understand the functional distribution of land use and buildings as shown in Figure 4 and Figure 5).

From Figure 4 and Figure 5, it can be observed that the two areas greatly differ in terms of land use characteristics. Municipio area, in consideration of its historical origin, has mixed-use buildings, e.g. commercial and/or tertiary uses on the ground and first floors, and residential use on higher floors. Centro Direzionale, on the other hand, has been developed during the 1980s and 1990s as a modern car-oriented CBD with a strict separation of tertiary and residential functions. In this area, high-rise residential towers are concentrated in the southern sector, while there are no mixed-use buildings. The characteristics of the functional distribution of land use in the two study areas are tabulated in Table 2 and the same has been depicted in the form of pie charts in Figure 6 and Figure 7.

| Area | Centro Direzionale | Municipio | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Land-use | Percent | Area (sq. m) | Percent | Area (sq. m) |

| Residential | 7 | 7660 | 1 | 1312 |

| Church | 3 | 2892 | 5 | 7769 |

| Commercial/Office | 81 | 86724 | 23.8 | 36448 |

| Public | 1 | 1737 | 15 | 21905 |

| School | 2 | 1862 | 0.4 | 470 |

| Mixed Land Use | 6 | 6590 | 54.8 | 82690 |

| Total | 100 | 107465 | 100 | 150594 |

The land use in Centro Direzionale has segregated residential (7%) and commercial/office (81%) sectors, while in Municipio, there is 54.8% of mixed land use (commercial/office/residential), 23.8% of commercial/office use, and only one percent (1%) of exclusively residential use.

Transit Oriented Development is based on diversity in land use as one of its major pillars, and the functional distribution of land use in Municipio is observed to be better aligned with the TOD principle of mixed land use of 54.8%, whereas Centro Direzionale has a meagre share of only six percent (6%). So far, Municipio has been observed to perform better in the aspects of densities of population, household, and employment, along with diversity in social structure and functional distribution of land use. Then, responses to the user/commuter questionnaire have been collected and analysed to examine the travel behaviour of residents and commuters.

To investigate the travel characteristics of residents and workers in the two study areas, a comprehensive user response survey was conducted. The interviews were conducted between 9 a.m. and 5 p.m., mostly in Municipio Square and Via Miguel de Cervantes, the most populated pedestrian spaces in the Municipio area, and along the pedestrian boulevard in Centro Direzionale. All interviews were taken during working days (Monday through Friday), following the usual working time in Italy.

Structured face-to-face interviews were used, with both close-ended and open-ended questions; the responses were recorded on an empirically designed questionnaire. The survey was able to collect 200 responses, distributed between the two areas. As per (Bartlett, Kotrlik et al., 2001), the required sample size at a confidential level of 90% for Naples with a one million population was 197; thus, according to this reference, the survey conducted for this research was able to achieve the required sample size. The responses were analysed in light of the objective of the study. The respondents were asked questions related to their residence, employment, and travel characteristics including trip purpose, mode of travel, travel time, and travel cost; even though tourists are often present in the Municipio area, they have not been interviewed. Average travel distance was obtained from Vehicle Kilometres of Travel (VKT) for each individual, calculated using the trip length and mode of travel. If the mode of travel is car or two-wheeler, the vehicle factor is taken as one, while in the case of a trip made by bus, the vehicle factor is 1/30, assuming the average occupancy of a bus as 30 passengers, moreover, the vehicle factor is taken as zero for trips made by walk or by bicycle.

The results of the survey response about travel characteristics are presented in Table 3. It was found that commuting behaviours were relatively diverse in the two study areas. In Municipio, for instance, the percentage of car owners was lower (65%) as compared to Centro Direzionale (71%); moreover, private car is much more used by those interviewed in Centro Direzionale than those interviewed in Municipio. Additionally, it was observed that people coming from outside the study area to Municipio have a greater inclination towards using public transport than using a private car. The scenario is quite different in the case of Centro Direzionale, where private car/motorcycle is preferred over public transport and walking. It is interesting to note that parking charges in Municipio are 5 - 7 Euros per hour, while in Centro Direzionale parking cost is around 1 - 2 Euros per hour with discounts on long-stay parking, amounting to 5 Euros per 24 hours. It can be assumed that the widespread availability of parking with low costs encourages access by private car/motorcycle to Centro Direzionale.

| Parameters | Centro Direzionale (responses in absolute number) |

Municipio (responses in absolute number) |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 100 | 100 |

| Gender Status | ||

| Female | 47 | 49 |

| Male | 53 | 51 |

| Trip Origin | ||

| Residence in Naples | 55 | 52 |

| (of which residing in the area) | (1) | (9) |

| Residence Outside Naples | 45 | 48 |

| Residence Factor | 0.02 | 0.17 |

| Travel Mode | ||

| Private Car/Motorcycle | 50 | 17 |

| Public Transport | 44 | 58 |

| Shared Car or Public Transport (variable) | 4 | 12 |

| Walk | 2 | 13 |

| Detail about commuters residing outside the Naples municipality | ||

| Outside Commuters by Public Transport | 25 | 38 |

| Outside Commuter by Car | 20 | 10 |

| Trip Character | ||

| Work | 61 | 58 |

| Education | 30 | 24 |

| Others | 9 | 18 |

| Employment & Travel Pattern | ||

| Travel up to 5 km | 55 | 52 |

| Travel more than 5 km | 45 | 48 |

| Car ownership | ||

| Car Owner | 71 | 65 |

| No Car Ownership | 29 | 35 |

|

Avg. Monthly Travel Expense (includes driving expenses, parking, and public transport fares) |

82 € | 52 € |

| Avg. per capita Vehicle Kilometres of Travel (VKT) | 15.5 | 6.6 |

Comparing the study areas in the light of travel mode choice, it can be observed that in Municipio public transport and walking account for 71 trips (58 people use public transport and 13 choose to walk); while this figure reduces to 46 in for Centro Direzionale (44 people use public transport and 2 choose to walk), highlighting a strong difference in mobility attitude. The cited differences result in higher transport costs, as witnessed by the average monthly transportation expenditure, corresponding to 52 Euros for Municipio, significantly lesser than that of Centro Direzionale - 82 Euros.

The study also observed that the Residence Factor, which is the ratio between residents in the study area to the residents in Naples Metropolitan Region, is higher in Municipio: this may be attributed to lower cost, better access to jobs, and accessibility and liveability. The study also found that thirteen percent (13%) of commuters in Municipio choose to walk as their mode of travel, as compared to Centro Direzionale, in which only two percent (2%) choose to walk, highlighting Municipio as a more walkable neighborhood in comparison to Centro Direzionale.

Generally speaking, it can be said that Centro Direzionale is more car-oriented than Municipio, discouraging public transport usage and active modes of transport. The analysis of the survey responses also found that the per capita Vehicle Kilometres of Travel (VKT) for Municipio was 6.6 kilometres, whereas, for Centro Direzionale, it was 15.5 kilometres. These figures suggest that mixed land use is more effective to contain the auto travel demand, as shown in Figure 8., which shows schematically the responses to the questions on gender, trip characteristics, car ownership, monthly transport expense, and mode of travel; the axis values in the figures are in percentages unless otherwise stated. As can be observed, the studied cases are similar in terms of the purpose of travel and gender, refer to Figure 9, while they show some differences in terms of transport choice, car ownership, and monthly transport expenses.

As already stated in the previous chapters, the study aims to help implement the TOD concept in existing urban areas and propose a method able to assess existing urban districts in the light of TOD tenets. A literature review revealed that, despite widespread literature on TOD, literature gaps exist about the aforementioned aspects. This study tries to bridge the cited literature gaps by comparing two areas within the city of Naples, Italy. The assessment is based on the collection and explication of socio-economic data and structured face-to-face interviews, with both close-ended and open-ended questions.

It was found that Municipio is characterised by a balanced and fine-grained functional mix of land use along with many multifunctional buildings and a better social structure. The scarcity of car parking resulted in higher use of public transport and active modes, lower transport costs, and shorter trip lengths. Good design of urban spaces encourages active transportation as exhibited in this area, which has been recently refurbished along with the opening of the metro station. In Centro Direzionale, tertiary functions prevail, with a strict separation of land uses: a sector with residential-only high-rise buildings and another sector with high-rise office towers with some commercial use. Space for car circulation and parking is placed underground, while the ground level is exclusively pedestrian. However, as already sketched, the high availability of parking and the direct link with urban motorways make Centro Direzionale a car-oriented district, with low use of public transport and active transport modes, high transportation cost, and long trips. Moreover, the area shows very low figures for inner-district commuting - i.e., people living and working in the district - as reported in Table 3: only one interviewed declared to live and work in the district. This may be explained by the lack of function mix.

People tend to consider Centro Direzionale socially unsafe, especially during nights and off-working hours, when robberies and criminal acts can happen, as witnessed by crime news. By contrast, in Municipio, the existence of mixed activities with different operating times of offices, shops, theatres, restaurants, etc. and different times of activities of residents, employees, people spending their free time, and tourists make the area busy during daytime, evening, and late night of every day; hence it can be assumed that these round-the-day activities contribute to keeping Municipio safer than Centro Direzionale. However, these statements are based on a perception of people and are not supported by a systematic analysis of crime figures, thus they should not be strictly considered as findings of this study. Even though some studies (Canfora and Corbisiero, 2014) consider Centro Direzionale as an example of sustainable urban development following the TOD principles, this research found that Centro Direzionale can be considered - from some points of view - less transit-oriented than Municipio. This study found that, despite its features with high-rise development, totally car-free spaces, and presence of a metro station, Centro Direzionale has the worst performance in terms of attractiveness of sustainable transport - i.e., public transport and walking. The traditional neighbourhood of Municipio performs better from many points of view in satisfying TOD requirements, such as mixed land use, higher population, households, and employment densities than Centro Direzionale.

The results suggest that a dense urban structure (as in Centro Direzionale) does not automatically yield good results in terms of the success of sustainable transport modes. In particular, it can be said that a widespread, cheap parking provision has a significant adverse impact on public transport use. Areas with high parking cost tend to divert trips to transit and the areas with abundant and cheap or free parking encourages private vehicle use (as in Municipio). On the other hand, the Municipio district seems to perform better in terms of sustainable transport, especially in terms of walking. This can be linked to higher social safety, due to the existence of activities during different times of the day and the street design. The aforementioned considerations can be translated into some – draft – recommendations to public authorities:

Regarding the three "Ds" of TOD – density, diversity, and design – it can be concluded that the influence of the "density" factor should not be overestimated; nonetheless "diversity" and "design", if accurately managed, can play a far more relevant role in promoting sustainable transport modes. This study is characterised by some limitations. The quality and newness of available data influenced the accuracy of results e.g., the information about social diversity, coming from the national census of 2011, is the most recent data available on this scale. Moreover, limitations can be represented by the size and composition of the sample of interviews: in fact, the limited sample of interviews could affect the precision of the results about travel behaviour. Furthermore, the selection of interviewed people can be not completely representative of the population residing in the area – e.g., in terms of age, gender, ethnic group, or wealth.

The study may be extended further to explain the relationship between land use diversity, density, and design on auto travel demand. Auto travel demand is dynamic; hence, it may not be possible to extract a land use mix that gives null auto travel demand, but the observations may be sought to arrive at the optimum mix of land uses that make auto travel to a minimal level. The study may also be extended to study the impact of other Travel Demand Management (TDM) measures like differential parking prices, congestion pricing, access to public transport, etc. on the auto travel demand.

Conceptualization, Rahul Tiwari and Antonio Nigro; methodology, Rahul Tiwari.; software, Antonio Nigro.; investigation, Rahul Tiwari.; resources, Rahul Tiwari and Antonio Nigro; data curation, Antonio Nigro.; writing—original draft preparation, Rahul Tiwari and Antonio Nigro.; writing—review and editing, Rahul Tiwari and Murthy VA Bondada.; supervision, Rahul Tiwari, Antonio Nigro and Murthy VA Bondada. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of the paper.

The authors would like to extend gratitude to the Association of European School of Planning (AESOP), Maulana Azad National Institute of Technology, University of Florence, and University of Naples Federico II for supporting the study and in particular Professor Francesco Domenico Moccia, University of Naples Federico II and Professor Valeria Lingua, the University of Florence for their guidance and mentorship.

This research was made possible by a grant of the award “YoungInvestigator Training Program 2019 - Regional planning and design, from theory to practices” promoted by the Department of Architecture of the University of Florence, with the contribution of Associazione di Fondazioni e Casse di Risparmio Italiane SpA (ACRI) in the context of the Association of European Schools of Planning – AESOP, the AESOP Young Academics group and AESOP thematic group on Regional Design.