2023 Volume 11 Issue 2 Pages 61-80

2023 Volume 11 Issue 2 Pages 61-80

A unified original townscape may affect the identity and value of the area. However, it is not easy to maintain the original design as time passes. This study aims to clarify the actual remaining state of exterior form within suburban detached residential areas and explore the influencing factors. For data collection, visual observation of the site and a literature survey on the housing map was conducted. For analysis, we conducted the cross-tabulation, chi-square test, and association analysis. The following results are obtained: 1) In about 80% of the lots, both planting belts and hedges are maintained after 23-37 years of development. The hedge is more likely to disappear than the planting belts, 2) Rebuilding, household alternation, and multiple flat parking spaces are three significant factors influencing the disappearance of planting belts and hedges. The impact of rebuilding is the predominant factor in the disappearance of both. Furthermore, the impact of rebuilding is strengthened when combined with household alternation or multiple flat parking spaces, and 3) The relationship between the remaining exterior features and duration after development by the areas and joining communal building agreements was not confirmed.

After the middle of the 20th century, suburban development expanded in many countries. Some countries in the depopulation phase, including Japan, are discussing how to aggregate residential areas. Therefore, suburban residential areas may not succeed if they are unappealing. The convenience, amenities, price, townscape, and other factors contribute to the appeal of the area (Kadono, 2000). Specifically, in residential areas that have been modernized and developed, physical and visual components foster their sense of place (Ghoomi, Yazdanfar, et al., 2015). The unique townscape in suburban detached residential areas contributes to the area's identity among the residents (Kaga, Tagawa, et al., 2013). Furthermore, residential green scenery can reconcile the various interests of residents (Schmid and Säumel, 2021). Fostering community attachment and interest encourages participation in activities that maintain and improve the residential area’s environment and leads to mutual support among the residents (Ito, 2017). Therefore, we consider the unique townscape of a residential area to be an important factor in considering the sustainability of a residential area. Some previous studies supported this consideration. For example, Yandri, Priyarsono, et al. (2021) regarded a scenic view of a residential area as one of the indicators of a sustainable residential area. Abdollahpour, Sharifi, et al. (2021) regarded an attractive landscape as one of the happy city indicators.

In Japan, the development of suburban residential areas accelerated after the rapid economic growth in the 1960s, which corresponds to the growth of the urban population and policy in the owing house (Kadono, 2000). Simultaneously, the diversification of housing construction methods and materials was accelerated with industrialization, losing its traditional style (Matsumura, 2004). Owing to the weakness of building design regulation in Japan, owners could build new own detached houses with free designs they like. Generally, this is one of the causes of the lack of harmony in the townscape in a suburban detached housing area. As Raymond (1932) pointed out, identities and harmony in the townscape of the residential area had weakened because of modernization and the diversity of housing production. We consider the unified exterior form as one of the measures to bring harmony to the townscape even with diverse building design. In some residential areas, the exterior form of each lot was well designed to ensure a harmonized townscape at the time of development. We consider the exterior form with unified design one of the unique characteristics affecting the areas' identity and charm.

However, it is not easy to keep the original design as time passes (Miyawaki, 2007; Nakai, 2008). Residents’ house improvement needs and understanding of the original concept may change over time. With the living household alternation due to sales and inheritance, residents’ needs and sense of value for the house and area may change dramatically. In addition, rebuilding a house may be a significant opportunity to change the exterior form. We consider that the well-designed original unified exterior form should be kept for the area's identity and charm. In this paper, “original” refers to the state when it was developed, and, “unified” means the state with a common design to harmonize the townscape. It does not mean “monotony”, which Raymond (1932) pointed out as one of the taboo designs in residential area townscape, such as lined up small houses with the same design “Unique” establishes the features that bring the area’s identity or representative.

This study explores the influencing factors in remaining or changing the original unified exterior form within the suburban detached residential area. As the original unified exterior, we focus on the two features, the hedge and planting belt. To clarify the actual remaining state of the two features, we conducted a visual observation on the site. As an influencing factor, we focus on (1) the number of parking spaces, (2) vacant houses, (3) household alternations, (4) rebuilding, (5) duration after development by a block, and (6) joining the communal building agreements by lot. For data collection about influencing factors, visual observation on the site for (1), and literature surveys for (2), (3), (5), and (6) were conducted. For analysis, we conducted the cross-tabulation, chi-square test, and association analysis. The detail of the survey and analysis is shown in Section 3.

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the literature review, and Section 3 provides the details of the survey and analysis. Section 4 explores the relationship between the remaining state of exterior features and each assumed potential influencing factor by cross-tabulation and the chi-square test, and Section 5 focuses on combining the influencing factors. In Section 6, we discuss the background of the disappearance of the exterior features and their measures. Finally, in Section 7, we conclude the paper with the future issue.

Several preliminary research focuses on the disappearance in the character of townscape or urban structure of the historical area in terms of the succession of traditions. For example, Subadyo, Tutuko, et al. (2018) focused on the public open spaces in the historical area of Indonesia and clarified their remaining state, and evaluated them based on historical and aesthetic, and functional value. Poomchalit, Suzuki, et al. (2018) focused on wooden houses in traditional trader communities in Thailand and clarified the state and condition of their decadence of them.

A certain amount of research focuses on the townscape of suburban residential areas developed before the second world war in Japan. Most of the target areas were developed for the upper-income class at the time, and have unique townscapes characterized by the relatively large size of lots, street patterns, trees, fences, hedges, and so on. Obata, Otsuki, et al. (2005) clarified the pattern of subdivided land, remaining components of the building, and exteriors features such as fences and trees, and hedges at the time of 78 years after development. Obata, Otsuki, et al. (2005) indicated that influencing factors of the component of exterior features are more about the individual situation and personal sense of values than initial conditions such as the lot size and ownership. Kage, Tagawa, et al. (2013) clarified the remaining state of scenic landscape resources, such as street patterns, large size lots, hedges, fountains, and residents’ identical evaluation of the resources, at the time 80 years after development. We referred to the methodology and concept of the former research targeting the residential areas developed before the second world war. Specifically, we targeted the residential areas developed after the high economic growth era because they are numerous and found all over Japan, and their uniqueness needs to be sustained.

Previous research, indicating the influencing factors of changing townscape targeting suburban residential areas developed after the high economic growth era, are divided by focusing points, violation of the communal building agreements, decrease in exterior green, and subdivision of the land. Summaries of their results and relation to this study are shown below. The backgrounds of the violation of the communal building agreement*1 were summarized as the residents' lack of understanding of the agreement and lack of interest in maintaining the townscape (Inui, 2011; Takahashi, 1987). This indicates a discrepancy between the agreement contents and residents’ housing needs such as the installation of storage and additional parking spaces (Inui, 2011; Takahashi, 1987). Subsequently, this study focuses on household alternation and rebuilding because they are expected to make the discrepancies apparent. A decrease in exterior green is affected by the increase in square footage and additional parking spaces due to rebuilding homes (Kamei, Sone, et al., 2005). However, the influence of household alternation on the existence of home exteriors was not mentioned nor clarified in previous studies. A subdivision of the land, considered the cause of townscape deterioration, occurred when homes were rebuilt with household alternations, especially in areas without communal building agreements (Suzuki, Ishiwatari, et al., 2011). It indicates that the combination of rebuilding and household alternations causes the townscape to change, and the agreement may control the subdivision of the land. We have the same perspective. However, we focus on the exterior form that characterizes the area’s townscape, not the subdivision of the land.

The originality of this study involves exploring the factors that influence the change of the unified exterior form while focusing on household alternations and rebuilding.

The research target area is the Satsukino residential area located in Mihara-ward, Sakai City, Osaka, Japan. The outline and the location of Satsukino are shown in Table 1 and Figure 1.

| Location | Satsukino-Higashi and Satsukino-Nishi, Mihara-ku, Sakai-city, Osaka-prefecture, Japan |

| Developer | TOKYU LAND CORPORATION |

| Duration of house selling | 1981-1995 |

| Total area of developing | about 0.77 million square meters |

| Total planned number of lots | about 1980 lots |

| Characteristics of house | Each lot size is about 200 square meters. Most of the houses are owned detached houses. At the developing time, most of the houses were built the wood by the developer. |

| Access to the metropolis | It is located about 18km away from Osaka city’s business district and commutable using bus and train. However, it takes more than 1hours because residents have to take a bus to get to the train station. |

| Population *1 | 5,052 people |

| Number of households *1 | 1,872 household |

| Rate of aging over 65 years old *1 | 33.7% |

Note: *1 According to the national census at 2015

The townscape of Satsukino is characterized by two distinctive exterior features. One is the planting belt with a 65 cm depth facing the street, and the other is a hedge shown in Figure 2. The planting belt was designed not only for the townscape but also for community forming. The developer designed it to be a semi-public space for residents’ communication*2 (Okawa, 1991). We consider that these two exterior features bring harmony to the townscape and identity of Satsukino in terms of scenery and community building. The effects are strengthened because the neighboring residential areas do not have such unified exterior features. Conversely, one of the reasons for the target area selection is that the two exterior features make it easy to keep track of the remaining exterior form.

Both features are inside the lot and owned by the individual resident who has the right to change them. They were installed in all houses at the time of development. Furthermore, the communal building agreements*1 mandated that they be maintained. This communal building agreement was concluded by the developer using a single agreement system.*1 The whole area is divided into eight areas according to the time of development, as shown in Figure 1. Each area has an alphabet ID from A to H; Area A is the oldest, and area H is the newest. The developing time difference between A and H is about 13 years. Each area has the original communal building agreement and committee, although the regulated contents are similar. Every 10 years, the committee submits a succession document showing the contents of the agreement and the location of joining residents’ lots to the local government to keep the agreement. However, if the committee does not submit the succession document, the agreement is saved automatically. Excluding area H, which submitted the succession document in 2016, all areas have not submitted the succession document to the local government within the last 10 years. This indicates that only area H maintains an updated agreement and map of joining residents’ lots. Comparing the description of regulated contents in the agreement, area H has the most detailed description (Itami, Kobayashi, et al., 2020). Some residents say that the agreement has lost substance. *3 If this is accurate, area H is assumed to manage the most effective agreement within the eight areas.

Figure 3 shows the occupancy state of the lots and houses in Satuskino according to the housing maps at two-time points (1997 and 2017). 97% of lots with houses and residents in 1997 have been in the same state in 2017. 46% of vacant lots and 87% of vacant houses in 1997 have changed into lots with houses and residents in 2017. This indicates that vacant lots and houses flow as real estate instead of being abandoned.

To explore the influencing factors on the changes of two features, we conducted surveys, assumed influencing factors, and analyzed the relation between both actual conditions. To determine the remaining state of the two exterior features, which are the planting belt, and hedge, we conducted visual observation on the site. During the development time, all the lots were designed with a hedge and planting belt. Thus, if we did not find the hedge and planting belt on the site, they were considered “DISAPPEAR.” For judging the remaining planting belt, if the shape exists with a total length longer than 0.5m, we considered it “KEPT.” For judging the remaining hedge, we considered the hedge and the fence covered by the plants as “KEPT.”

As the potential influencing factors on the changes of the two exterior features, we focused on (1) the number of parking spaces, (2) vacant houses, (3) household alternations, (4) rebuilding, (5) duration after development by a block, and (6) joining the communal building agreements by lot. We hypothesized that a larger number of parking spaces, vacancies, alternating households, and rebuilding would influence the disappearance of two exterior features. Furthermore, we hypothesized that the longer the time after development, the more two features disappear. Subsequently, we hypothesized that participation in communal building agreements prevents the disappearance of two features. To determine the condition of expected influencing factors, we conducted visual observation on the site for (1) and (4), and literature surveys for (2), (3), (5), and (6). The details of data collection methods are shown in Table 2.

| Target item | Way of survey | Contents and judging criteria |

|

Form of exterior (planting belt, hedge, parking space) |

Visual observation on the site*1 |

Planting belt: KEPT or DISAPPEAR (If the shape*2 exists with a total length longer than 0.5m, we judged it as KEPT*3), ground finishing, and planting. Hedge: KEPT or DISAPPEAR (If the plant is used covering the fence, we judged it as KEPT*3) Parking Space: The number of spaces for parking and form (flat or multi-stories) |

| Household alternation | Literature survey | Comparing housing maps*4 from two-time points (1997*5 and 2017), we identified vacant lots (lot without building), vacant houses (lot and building without resident’s name), and household renewal based on changes in resident’s names. |

| Rebuilding | Visual observation on the site*1 | The houses with different designs*6 from the original house built at the developing time were considered as rebuilt. If it was hard to judge, it was classified as “hard to judge. “ |

| Joining the communal building agreement | Literature survey | Checking the map attached with the communal building agreement of area H updated in 2016. It shows the location of lots where residents join the agreement. |

Note: *1 We conducted the field survey in November and December 2018.

*2 It does not matter the ground finishing and the planting greens.

*3 There are no specific regulations about the length of planting belts and hedges in the communal building agreement. Therefore, this judging criterion was made for the research.

*4 Zenrin Corporation (1997) and Zenrin Corporation (2017).

*5 Since the housing sales ended in 1995, the housing map in 1997 was used as the initial stage of development. Therefore, the household alternation between 1981 and 1996 was not grasped in this survey.

*6 The original houses have resembled patterns or details, such as the shape and location of windows and doors and the shape of the lean-to roof.

Figure 4 shows the contents of the analysis in this paper. In Section 4, we explore the relationship between the remaining state of exterior features and each assumed potential influencing factor by cross-tabulation and the chi-square test.

In Section 5, we focus on the combination of the four items, which confirmed the relationship with the exterior features in Section 4. It is because some factors have a relation in occurrence, and the combination of factors gives us a hint to understanding the mechanism of influence. Association analysis is used for analysis. It is a statistical method for extracting association rules (combinations of events with strong simultaneity or relations, such as when event A occurs, another event B occurs) from large amounts of data. The result of the analysis is expressed as a “combination of left-hand side (LHS) ⇒ right-hand side (RHS).” Furthermore, it is explained: “When the combination of items on the left-hand side is selected (happened), the items on the right-hand side tend to be selected (happened).” In the association analysis, there are three indexes for evaluating the extracted rules. *4 We use the lift to focus more on how the left-hand side influences the right-hand side. A larger lift value means the left-hand side has a stronger influence on the right-hand side. If the lift is larger than 1.0, the left-hand side is considered influential on the right-hand side.

At the beginning of this section, we show the remaining state of each planting belt and hedge. We also explore the relationship with the remainder of the exterior features and each potential influencing factor, (1) the number of parking spaces, (2) vacant houses, (3) household alternations, (4) rebuilding, (5) duration after development, and (6) joining communal building agreements by cross-tabulation and the chi-square test.

Overview of the remaining state of two exterior featuresThis section establishes an overview of the remaining state of two exterior features. The target is 1,896 lots, excluding vacant lots and lots under construction at the time of the field survey (2018). Figure 5 shows the remaining state of the planting belt, and Figure 6 shows the remaining state of the hedge. “No Need” refers to the lots that hardly have the planting belt and hedge because of the form of the lots, such as corner lots and flagpole lots. On these lots, the road boundary line is short, and most of the line is used to access the parking lot. A total of 64 lots are “No Need” in this survey.

As shown in Figure 5, we observed the surface finish (soil or other), presence of planting, and remain of form. We categorized considering the finish and planting because the belt without planting does not work for making continuous green into the townscape. Overall, about 92% of the belts kept their form, and about 83% maintained the soil surface and planting. However, while maintaining the form, about 4% of lots have no planting, and about 5% have a surface other than soil such as concrete and block. As shown in Figure 6, hedges are kept in about 80% of the total lots, and 17 % of the lots lost the hedge. This is about 13% more than the disappearance of the hedge (about 4%). Therefore, it can be said that a hedge is more likely to disappear than a planting belt.

Figure 7 shows the number of lots according to the remaining state of the planting belt and hedge, excluding the 64 “No Need” lots. A total of 1,498 lots keep both planting belts and hedges (81.8% in total), 249 lots keep only planting belts (13.6% in total), 76 plots lose both features (4.1% in total), and nine lots keep only hedges (0.5% in total). Although they are often kept as a set, the planting belt seems more likely to be kept, and only the hedge is rarely kept

Remaining state of two exterior features by the state of parking spaceIn this section, we focus on the number and form of the parking spaces and explore the relationship with the remaining state of the exterior features. The analysis sample includes 1,832 lots. At the time of development, parking lots were planned with one parking space per lot. At the time of the field survey (2018), 698 lots (about 38% in total) have two or more parking spaces. Most of them are flat type two-space lots (623 lots). However, there are also two-space multi-story lots (23 lots) and three-space lots (57 lots). From this section, the continuation of the planting belt and the hedge is classified into four categories according to the existence of each. “No Need” lots are excluded from the analysis sample. As index in the figures, “+” refers to kept and “-” refers to disappeared. For example, “Belt+/Hedge-” means that the belt is kept, and the hedge disappears.

As shown in Figure 8, as the number of flat parking spaces increases, the planting belt, and the hedges disappear. We conducted a chi-square test on the remaining state of the two exterior features and the number and form of parking spaces, and a significant difference was found (χ2 (9) =293.3, p < 0.01). We confirmed that the additional parking space encourages changes to exterior features, as the previous studies showed (Inui, 2011; Takahashi, 1987). However, even if the number of parking spaces is two flat spaces, about 76% of the cases keep both planting belts and hedges, as shown in Figure 8.

In this section, we focus on vacant houses and explore the relationships with the remaining state of exterior features. The analysis sample includes 1,832 lots excluding the 64 “No Need” lots. As shown in Figure 9, belts and hedges disappear more from lots of vacant houses than occupied houses, which is about a 13% difference. A chi-square test was conducted on the continuation of the two exterior features and vacant houses, and a significant difference was found (χ2 (3) = 8.237, p = 0.041 < 0.05). The possibility that vacant houses encourage the disappearance of exterior features is confirmed.

This section provides an overview of the status of household alternation and rebuilding. Furthermore, we explore the relationship with the remaining state of the exterior features. The analysis sample includes 1,819 lots inhabited at both time points (1997 and 2017). We exclude the vacant houses from the analysis sample to avoid the impact.

As shown in Table 3, household alternation was observed in 519 lots (about 29% of the total). It indicates that about 29% of the households occupied and vacated the lots after 23-37 years of development. In addition, 1,661 lots (about 91%) have not been rebuilt. However, among the lots with household alternation, the percentage of lots that have been rebuilt is about 11%. This is about 5% higher than lots without household alternation. A chi-square test was conducted on 1,785 lots that can be judged the state of rebuilding, and a significant difference was found (χ2 (1) = 15.87, p < 0.01). It was confirmed that household alternation might encourage rebuilding.

| Rebuilding | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | Hard to Judge | Under-Construction | Total |

% column |

|||

| Household alternation | No |

Number of lots % in row |

1,203 92.5 |

69 5.3 |

27 2.1 |

1 0.1 |

1,300 100 |

71.5 |

| Yes |

Number of lots % in row |

458 88.2 |

55 10.6 |

4 0.8 |

2 0.4 |

519 100 |

28.5 | |

| Total |

Number of lots % in row |

1,661 91.3 |

124 6.8 |

31 1.7 |

3 0.2 |

1,819 100.0 |

100.0 | |

Since there is a strong relationship between household alternation and rebuilding, we use the combined variable of four types with both variables. A total of 1,730 lots, excluding lots where rebuilding is hard to judge and under reconstruction, and 55 lots where hedges and planting belts do not need to be installed, are used as analysis targets.

As shown in Figure 10, high percentages of both planting belts and hedges are depicted in the following order: no household alteration and no rebuilding (about 87%), household alteration and no rebuilding (about 80%), no household alternation and rebuilding (about 67%), and household alternation and rebuilding (about 37%).

Since there is a strong relationship between household alternation and rebuilding, we classified them into four types (I/ II/ III /IV) and conducted a chi-square test for two groups with one condition fixed. As a result, shown in Table 4, significant differences were confirmed at the 1% level in all two pairs comparing rebuilding (I and II, III and IV) and two pairs comparing household alternation (I and III, II and IV) as shown in Table 4. The χ2 value is more significant for the two pairs comparing rebuilding (I and II, III and IV) than for household alternation (I and III, II and IV). These results indicate that both household alternation and rebuilding affect the disappearance of planting belts and hedges, and the effect is more significant in rebuilding.

| Compared pair | Pearson χ2 | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Examining the influence of rebuilding |

The differences according to rebuilding in the samples without household alternation |

Ⅰ and Ⅱ | 20.92 | <0.01 |

|

The differences according to rebuilding in the samples with household alternation |

Ⅲ and Ⅳ | 44.11 | <0.01 | |

| Examining the influence of household alternation |

The differences according to household alternation in the samples without rebuilding |

Ⅰ and Ⅲ | 14.03 | <0.01 |

|

The differences according to household alternation in the samples with rebuilding |

Ⅱ and Ⅳ | 10.44 | <0.01 |

This section focuses on (5) duration after development by a block and (6) joining in the communal building agreements by a lot. The analyzing target includes 1,730 lots, the same as 4.4.2. As mentioned in 2.1, the areas’ ID indicates the order of development time. Area A is the oldest. Furthermore, area H is assumed to manage the most effective agreement.

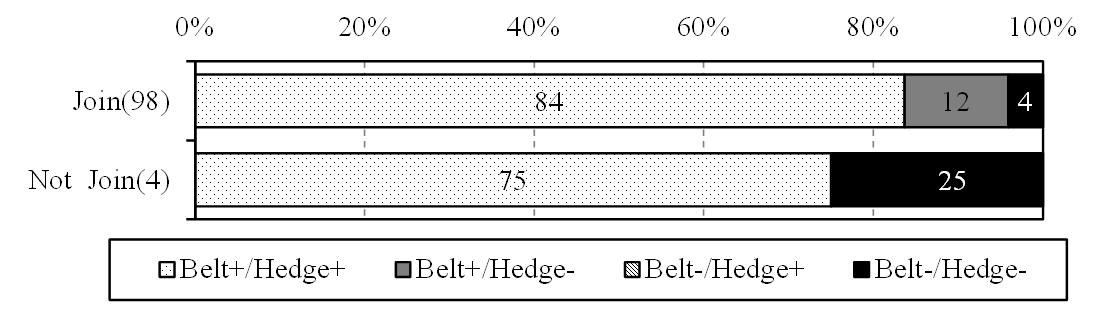

As shown in Figure 11, the relationship between the remaining state of exterior features and the area is not confirmed. It indicates that the time after development has not yet affected the remaining state of exterior features. One of the assumed reasons is that the status of household alternation and rebuilding is not related to the area, as shown in Figure 12. As shown in Figure 11, the percentage of keeping planting belts and hedges is not exceptionally high in area H, where the communal building agreement is assumed to be managed effectively. To confirm the effect of joining the communal building agreement, we conducted cross-tabulation in all the lots of area H where the joining status of the building agreement for each lot in 2016 was available.

As shown in Figure 13, although only four lots are not joining, three lots keep planting belts and hedges. Contrarily, in the joining lots (98 lots), about 12% have lost the hedges, and about 4% have lost both. From this, it was confirmed that the effect of the building agreement is not absolute.

In Section 4, four items were confirmed as influencing factors in the disappearance of planting belts and hedges: (1) number of parking spaces, (2) vacant houses, (3) household alternation, and (4) rebuilding. These four items can occur simultaneously, and some items have a relation in occurrence. In this section, we focus on the combination of the four items and explore the impact on the disappearance of planting belts and hedges by conducting an association analysis. In this analysis, the items on the left-hand side of the association rule are established as follows:

We conducted an association analysis for two equations with two different results shown on the right-hand side of the association rule. One is the disappearance of the planting belt, and the other is the disappearance of hedges. There are 1,799 target lots, and they all exclude vacant lots (33 lots), disappeared lots (3 lots), lots with no need to set the two exterior features (64 lots), lots under construction (3 lots), and lots on which rebuilding was difficult to determine (33 lots).

The results regarding the disappearance of the planting belt are shown in Table 5. The results of the disappearance of the hedges are shown in Table 6. There were seven rules with a lift larger than 1.0 for the disappearance of hedges and six rules for the disappearance of planting strips. The top five combinations of items on the left-side hand are the same for both disappearances. This indicates that the combinations of conditions for the disappearances of hedges and belts are generally the same.

First, we discuss the common trends in the disappearance of planting strips and hedges. All of the top four combinations include rebuilding, and even rebuilding alone has a lift value larger than 1.0 (3.24 for the belt [B4] and 1.60 for the hedge [H4]). It was confirmed that rebuilding had a strong impact on the disappearance of planting belts and hedges. However, not only rebuilding but also the combination of multiple parking spaces (+0.49 for the belt [B3], +0.20 for the hedge [H3]) and household alternation (+0.73 for the belt [B2], +0.49 for the hedge [H2]) increases lift. The highest lift is the combination of the three items, rebuilding, household alternation, and multiple parking spaces (4.35 for the belt 2.16 [B1], 2.28 for the hedge [H1]).

From here, we show the trends for the disappearance of planting belts and hedges, respectively. Rebuilding, household alternation, and multiple parking spaces are considered the three major items that affect the disappearance of both. In all rules composed of three items, the lift is more significant for the disappearance of the planting belt than for the disappearance of hedges (for example, in all three items’ combination, 4.34 for the belt [B1] and 2.28 for the hedge [H1]). A vacant house appears only in Table 6 ([H6] and [H7]), which is for the disappearance of the hedge. Conversely, only in the disappearance of the planting belt, was a rule extracted where the left-hand side had only multiple parking spaces [B6].

|

Rule ID |

LHS | support | confidence | lift | Number of the cases | ||

| [B1] | Rebuilding | Household alternation | Multiple parking spaces | 0.023 | 0.344 | 4.335 | 22 |

| [B2] | Rebuilding | Household alternation | 0.024 | 0.315 | 3.973 | 23 | |

| [B3] | Rebuilding | Multiple Parking spaces | 0.035 | 0.296 | 3.728 | 34 | |

| [B4] | Rebuilding | 0.037 | 0.257 | 3.243 | 36 | ||

| [B5] | Household alternation | Multiple Parking spaces | 0.040 | 0.150 | 1.892 | 39 | |

| [B6] | Multiple Parking lots” | 0.069 | 0.103 | 1.302 | 67 | ||

|

Rule ID |

LHS | support | confidence | lift | Number of the cases | ||

| [H1] | Rebuilding | Household alternation | Multiple parking spaces | 0.040 | 0.672 | 2.284 | 43 |

| [H2] | Rebuilding | Household alternation | 0.042 | 0.616 | 2.095 | 45 | |

| [H3] | Rebuilding | Multiple parking spaces | 0.057 | 0.530 | 1.803 | 61 | |

| [H4] | Rebuilding | 0.062 | 0.471 | 1.603 | 66 | ||

| [H5] | Household alternation | Multiple parking spaces | 0.085 | 0.346 | 1.177 | 90 | |

| [H6] | Household alternation | Vacant | 0.012 | 0.325 | 1.105 | 13 | |

| [H7] | Vacant | 0.012 | 0.317 | 1.078 | 13 | ||

To summarize the abovementioned results, rebuilding, household alternation, and multiple parking spaces are the three significant factors in the disappearance of planting belts and hedges. The impact of rebuilding is the predominant factor in the disappearance of both. Furthermore, the impact of rebuilding is strengthened when combined with household alternation or multiple parking spaces. The impact of vacant houses alone on the hedge and multiple parking spaces alone on planting belts was confirmed.

We considered rebuilding and household alternation hard to avoid with the passing time. Therefore, we discuss the multiple parking spaces, which is one of the primary factors in the disappearance of the planting belt and hedge. At the time of development, every lot had one parking space. However, many residents in Satsukino need multiple parking spaces. This is confirmed by the fact that about 82% of lots with rebuilding have multiple parking spaces, and about 35% of lots without rebuilding have them. Additionally, on-street parking using the planting belt without green is often observed on the site, as shown in Figure 14. We assumed two backgrounds indicate the high need for multiple parking spaces: one is a change in the lifestyle of the residents, and the other is the lack of facilities in Satsukino. The lifestyle changes have occurred because of moralization, a decrease in homemakers, *5 aging residents, and so on. Regarding the facilities, the lack of train stations and attractive shops*6 is assumed to promote the need for a second car. However, it is not impossible to keep two exterior features with two flat parking spaces, as shown in Figure 15. Various designs to keep the planting belts and hedges are observed. The design depends on the original lots' conditions (approach ways for people and cars, arrangement of parking lots, hedges, and planting belts). Therefore, sharing design tips to keep exterior features with multiple parking spaces among residents may help remain exterior features. Contrarily, making a common parking area using vacant lots is also one of the measures.

Some results indicate residents’ burden of planting maintenance, including cutting weeds. For example, some planting belts lost the planting and soil surface. A hedge, which is assumed to be more of a burden to maintain than a planting belt, has disappeared more than the planting belt. This feeling is assumed to grow especially when the owner of the vacant house is aged. If the owner does not maintain the hedge, it grows large and causes problems with the neighbors. This fact motivates the owner or resident to cut down the hedge. Joint green management and joint ordering would be one of the solutions.

In the future, there will be more rebuilding and household alternation, and it will bring about the disappearance of more exterior features. We suggest the residents discuss whether the unified exterior form should be kept, which parts should be kept, and what measures they should take before it is too late.

This study aims to clarify the actual condition of the remaining state of the unified exterior form and its influence on factors in the suburban detached residential area. The results are summarized as shown below.

a) In about 80% of the lots, both planting belts and hedges have remained. The hedge is more likely to disappear than the planting belts.

b) Rebuilding, household alternation, and multiple flat parking spaces are three major influencing factors in the disappearance of planting belts and hedges. The impact of rebuilding is the strongest factor in the disappearance of both features. Furthermore, the impact of rebuilding is strengthened when it is combined with household alternation or multiple flat parking spaces. The impact of vacant houses on the hedge and the impact of multiple parking spaces on planting belts were confirmed.

c) The relationship between the remaining state of exterior features and duration after development by the areas was not confirmed. One of the assumed reasons is that the status of household alternation and rebuilding are unrelated to the duration after development.

d) The relationship between the remaining state of exterior features and joining communal building agreements by a lot was not confirmed. This indicates that the effect of the communal building agreement is not absolute.

The limitation of this study is that we cannot generalize the results because we targeted only one area. Since the target area is less than 30 years old, the results are considered on the way. Furthermore, the significance of keeping two exterior features in terms of townscape and identity of the area was not discussed although it seems a fundamental idea for this study.

In future research, since our survey method is applicable to the other areas, we would like to survey the other areas and compare the results to obtain general knowledge. And we would like to continue surveying Satsukino to grasp the changes over time. It is assumed that more rebuilding and household alternation will bring more disappearance of exterior features. We may see the effect of joining communal building agreements on the remaining exterior features in area H, where the communal building agreement is assumed to be managed effectively. Furthermore, we would like to explore how residents recognize the townscape, and remaining exterior features including the burden to maintain, and the identity of the area by questionnaire or interview survey. Subsequently, we would like to discuss what exterior features are needed to keep the identity of the area and practical measures to maintain the identity.

Conceptualization, E.I.; methodology, E.I. and T.A.; field survey, E.I. and F.K.; result analysis, E.I., T.A., and F.K; data curation, E.I. and F.K.; writing, E.I.; supervision, K.I., T.Y., and T.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of the paper.

Part of this research was funded by Tokyu Fucoidan R&D Centre, Inc.

*1 A communal building agreement is a voluntary agreement among residents (landowners). The function and physical conditions of the land and building are regulated. However, it does not have legal binding. The joining residents should establish the building agreement management committee. The committee reviews and checks new building or remodeling projects, and takes measures in case of violation. Residents can choose whether they join the agreement or not. If they do not join the agreement, the lots are considered the excluded area. There are two types of concluding types of agreement, one is the single concluding type, and the other is the residents’ initiative concluding type. Developers use the single concluding type for new residential area development, and residents buy the land with the agreement given by the developers ( Takahashi, 2004).

*2 According to the developer ( Okawa, 1991), the part of the curbstone of the planting belt is wide to allow people to sit for a chat. If the residents maintain the planting on the street, it may cause a conversation with neighbors.

*3 In the free answers of the questionnaire survey on the residents in Satsukino in 2017 ( E. Itami, K. Itami, et al., 2019), complaints about the increase in the violation of the communal building agreement (8 opinions), demand on neighbors to follow the agreement regulation (4 opinions) were observed.

*4 Three evaluation indexes’ explanations and threshold values in this analysis set by us are shown in Table 7.

| Evaluation Index | Explanation | The threshold value in this analysis |

| Support |

The probability of the rule appearing in the entire sample |

>=0.01 More than 1 case in 100 of all samples. |

| Confidence |  The probability of appearing the rule in the sample selecting on left-hand side items The probability of appearing the rule in the sample selecting on left-hand side items

|

>=0.05 One out of every 20 cases on the left-hand side corresponds to the right-hand side. |

| Lift |  The ratio of confidence by the probability of selecting on right-hand side items in the entire sample The ratio of confidence by the probability of selecting on right-hand side items in the entire sample

|

>=1.0 The minimum value at which the left-hand side is considered to be influential on the right-hand side. |

*5 According to the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare statistics, households with housemakers in Japan were approximately 63% and 32% in 1981 and 2019, respectively. Even in the target area, Satsukino, more than half of households moved in the recent 20 years are dual-income families, according to our questionnaire survey in 2019.

*6 In the free answers of the questionnaire survey on the residents in Satsukino in 2017 ( E. Itami, K. Itami, et al., 2019), complaint about the inconvenience of public transportation (97 opinions), dissatisfaction with the shops in the center district (47 opinions), complaints about on-street parking and lack of parking spaces (10 opinions) were observed.