2023 Volume 11 Issue 3 Pages 172-191

2023 Volume 11 Issue 3 Pages 172-191

The Gotong Royong culture, which is the hallmark of the Bajo community, continues to experience changes due to interactions with mainland people. As a result, the cultural values of Gotong Royong have been abandoned. Efforts to restore local wisdom, such as the Gotong Royong culture, are urgently needed in this era. This research aims to innovate by reintroducing this culture, particularly in housing and housing development cooperation. The reapplication of local wisdom (Gotong Royong culture) in this study is intended to ensure that the characteristics and identities of the Bajo people remain the basis for building their social capital. The researcher used a qualitative descriptive method with inductive and deductive approaches, along with a Value Engineering approach. This research was conducted within the Bajo Tribe's location, situated in Kabalutan Village, Tojo Una Una Regency, Central Sulawesi Province, Indonesia. The results of the study found that the application of the Gotong Royong culture to the Bajo community in building houses and housing produced efficiency and effectiveness. It was efficient because it reduced development costs and effective because it took advantage of free time to construct houses, fostering a sense of togetherness among fellow Bajo tribespeople and strengthening cooperation. Thus, Gotong Royong activities serve as a means of building effective social networks that can reduce the cost of constructing houses and revive the culture of Gotong Royong.

The history of social development extends from primitive society to modern civilisation and then enters the postmodern era. Changing societal needs accompanied this movement, and has impacted various community groups. Urban communities, supported by human resources and efficient economic cycles, have experienced significant growth, giving rise to a capitalist and individualist culture. From an architectural perspective, the growth of urban culture, supported by industrial development, has greatly influenced people's lives and is seen as a measure of success (Healey, 2009).

On the other hand, rural or urban areas with limited potential experience obstacles in their development. Consequently, their progress remains minimal in terms of the human and economic resources they have. However, certain areas with considerable natural resource potential, such as mining, thrive and become satellite cities in the midst of forests. These cities are flooded by residents who come to work to fulfil their daily needs, becoming centres of economic growth and a source of regional income. These developments affect the cultural life of a heterogeneous society (Dalsgaard, 2014).

The Bajo tribe is a tribe that has insufficient human and environmental resources due to their coastal location, which faces significant pressure from societal changes. The condition of the Bajo people, characterised by minimal resources and a low level of education (typically elementary to high school education), coupled with the lack of territorial rights over coastal resources, hinders their economic access and development. For instance, banks generally do not want to provide working capital assistance to the Bajo community, so the opportunity to profit from growing their business opportunities in the marine sector is hampered.

The interaction of the Bajo people with the mainland significantly influences the tribe’s way of life, and the influence of global culture into the Bajo community has led to reduced adherence to local cultural values. As a result, the local culture that once characterised their lives, such as the culture of Gotong Royong as a unifying force or social bond, has turned into an individualistic culture (Sirajuddin, 2020).

Rationalisation of customary or ancestral rules has developed new thoughts that have influenced the role of standardised rules. Several aspects of their everyday practices have been unable to keep up with existing developments, so have been abandoned. Some customary laws have experienced degradation due to the rationalisation of principles, and in some cases, local wisdom has been entirely forsaken. For example, Gotong Royong customs, which were very popular among traditional societies in the past, both pre-modern and modern, have experienced a decline in significance, whereby some tribes have abandoned them and made them a thing of the past. In some cases, Gotong Royong culture has been replaced by a new participatory culture (Safin, Dorta, et al., 2016).

The existence of a Gotong Royong culture, which used to be the lifeblood of society and moved people to build social capital, is now seen as less effective and less efficient (Sirajuddin, 2020).

The above analysis raises the question of whether or not the culture of Gotong Royong in the Bajo community is efficiently and effectively applied under current conditions. Additionally, it prompts us to explore how this culture can grow and maintain its existence in society. In answering these questions, innovation and social engineering are needed to determine the impact of cooperation on the effectiveness and efficiency of the Bajo tribe's lives. This can be achieved through pilot activities aimed at building houses in Kabalutan Village.

The Bajo people used to be a society that appreciated the local wisdom of their ancestral heritage. However, the passage of time has eroded this local knowledge, including Gotong Royong, such that it has even been almost forgotten. Efforts to restore the local wisdom of cooperation requires research activities related to innovation and engineering. The potential to improve lives through innovation and engineering is intended to heighten competitiveness. It aims to create access to the economic sector and increase knowledge and skills required to compete in today's modern life. The existence of indigenous peoples will continue if their social environment can be maintained and adapted to the times (Philokyprou, Michael, et al., 2021).

The description above shows that in the current postmodern era, efforts to improve the lives of traditional societies necessitate adjusting old values to align with new values in accordance with the times. This thinking underlies the aim of this research, to evaluate the effectiveness of the Gotong Royong tradition in cluster house construction where the Bajo community in Central Sulawesi has been selected as a case study for innovation and engineering.

This literature review is intended as background knowledge for researchers, to provide a reasonable understanding and to complement researchers’ insights without hindering their study or analysis of problems. The scope of the literature includes 1) Aspects of Planning Pragmatism, 2) Concepts of Local Wisdom, 3) Settlements, 4) Aspects of Social Change, 5) Classical Theory, and 6) Modernisation Theory.

Aspects of Planning PragmatismThe development of the concept of pragmatic planning has emerged from various perspectives related to the influence of practical philosophy on nature and purpose. Pragmatic philosophers, as well as “neo pragmatists”, have contributed significantly to the development of the concept, identifying the influence of planning as a rational process. To transform transformative systemic work, it is considered essential to have practical ideas that emphasise planning as a valuable social learning activity (Healey, 2009). Pragmatism allows this to be applied by adapting traditional culture to today's postmodern culture. Pragmatism based on rationalist concepts is used to adapt traditional culture to contemporary culture, while conventional values can still coexist in society, and society can continue to develop according to the demands of the times (Dalsgaard, 2014).Philosophically, the pragmatic concept forms the backbone of design thinking. Pragmatists have contributed a lot to the design process; according to Dalsgaard (2014), failsafe pragmatist John Dewey proposes further study of the central ideas of design thinking. The arguments show a significant link between practical perspectives and design thinking. The pragmatic concept articulates a concern for substance by designing thoughts and attitudes that are well-developed, coherent, make sense, and can be valuable on both theoretical and practical levels. In theory, information and inspiration encourage the development of design discourse towards a rational context, while operationally, pragmatic thinking expects this information to guide design and aid in understanding the management of the design process (Dalsgaard, 2014).

The concept of pragmatism in the design process can help integrate traditional activities with everyday activities, allowing old values to be developed while integrating with current values, such as social and economic values, which can interact to form harmony in design.

Encoding research can obscure the holistic construction and planning paradigm, which can be followed up by developing sustainable planning, enabling the creation of various approaches and policies for sustainable development. The pragmatic philosopher William James saw a dichotomy between sustainability and policy planning that had existed for more than a century. This has influenced the development of development thinking and planning, as those who believe in the importance of more and better information are crucial to addressing sustainability challenges because they rely on the power of data as sustainability capital.

The philosophy of pragmatism, when related to sustainable development, links development perspectives with planning and policies. The dynamics of development thinking are translated into understanding and initiatives, providing a pragmatic framework for planning sustainability as the foundation of sustainability. Understanding the practical theory of truth and rationality, integration, and process serves as the basis for thinking about sustainability and human experience, which represents a test stage for shared values. Contributing to the evolutionary process of pragmatic thought, environmental philosophy’s work deals with many aspects of practical utility in sustainable development.

With the cooperation of planners and community members toward a common understanding, continuous communication and interaction processes need to be maintained. This process should show context and story alongside scientific and statistical models. Essential steps towards sustainability are made through the overall planning profession as a whole (Safin, Dorta, et al., 2016). Thus, the concept of pragmatism can be used as an agent in re-articulating local cultural values within a global culture.

Concepts of Local WisdomExisting local wisdom can be a unique and attractive solution that fosters strong community bonds. These communities have characteristics reflected in their social and physical environments. Thus, the community (tribe) reflects a fixed pattern specific to their place and is related to the history of the formation of the neighbourhood (Van der Linden, Dong, et al., 2019).

Tribal opinions related to economic aspects speak to a broad area, with the central function of a group arising from the interpretation of a site, land, or piece of land that is subsequently transformed into a place to live (Farreny, Oliver-Solà, et al., 2011). An environment with specific natural characteristics and spatial structures in the form of plains, valleys, or ponds (basins) is a space. These spaces are equipped with natural elements, such as rocks, plants, water, and orientation influenced by their topography, and which affect the relationships between location, light, weather, and biological conditions. The development of social capital formed in an area is a medium for people to interact; settlements are interpreted as housing guidelines for human habitation, where settlements have elements of both culture and civilisation (Akil, Pradadimara, et al., 2022). The structure and shape of a house and its procurement are considered as a manifestation of the culture of the community. A house is a shelter from climate and weather (hot, cold, rain, and wind) and is a place to live because of its function as a place of rest, a place to build a family, and even a place to work. Human responses to housing vary depending on where they are located, as they associate houses with various aspects, such as social, cultural, and physical aspects. The house is an area where humans live, which is physically related to the relationship between fellow residents as a community (Rapoport, 1969).

Some people have built houses in several areas, giving birth to inland settlements with traditional houses as a reference, and have constructed these according to local customs and characteristics. Where this occurs, the formed community tends to live in that place for generations, so it is considered a place of birth or hometown (Siradjuddin, 2020).

SettlementsSettlements serve as places where humans interact with others, nature, and natural rulers, and show the embodiment of the physical container of a place to live. They are areas where people gather, live together, and build houses with all the necessary facilities. Settlements are also a collection of places where people live, form a community, work, and communicate (Safin, Dorta, et al., 2016).

The house is an element of the village that fills and forms a dynamic balance and expresses every part and every scale of the settlement’s evolution. The settlement is an ecological unit that is interrelated by each of its elements. The existence of customary law does not show a simple causal relationship, but rather a statistical direction of change (Porchezhian and Irulappan, 2022). For example, the application of customary law processes related to the microcosm concept in the Kaili community’s understanding and application of lifestyles in smaller environments, such as in homes, villages, and large settlements. This concept of a microcosm within the Kaili community is reflected in every housing unit in the broader environment (Siradjuddin, 2015). The sacred space, believed to be a container for the rulers of nature on a micro-scale, is an application of protection. Its existence is supposed to protect To Kaili from disasters and disturbances from spirits, such as evil spirits around them. Around their buildings, To Kaili can usually prevent such a spirit by keeping sacred objects believed to drive away ghosts, or disasters, from entering the house (Montgomery, Wartman, et al., 2021).

Aspects of Social ChangeThe philosophy of social change in Indonesia is different from the context of Western philosophy, especially Greek philosophy. The relationship between ideas and human behaviour is consistently observed in everyday life. Environmental philosophy in Indonesia is related to seven ideas: 1) Nature and human life cannot be separated; 2) Nature includes the natural environment and biological environment; 3) The natural environment continues to grow; 4) Observations of human nature are related to the dimension of time; 5) The growth of society produces maturity in every human being (civilization); 6) Pattern discovery is a typical growth trait; and 7) Growth occurs through certain stages, known as regular and systematic growth. Human growth follows directions and patterns toward perfection. The resulting idea develops through certain stages, forming a straight line called an imaginary line (Baek, Kim, et al., 2018).

Classical TheorySociological theory has become an essential rationale and mainstay for the development of later sociological theories. Among the ideas that have emerged are idealism, materialism, and an economic system that has led to the dynamics of social change (Baek, Meroni, et al., 2015). The thinking that influences the theory of social change is rationalism, so in society, specific interest groups emerge, such as economic class, social status, and political interest groups. The formation of different models exists among people based on certain conditions. The existence of rationality in human thought can function independently for each individual, while at the same time it can be a reference for people’s behaviour (Kempenaar and van den Brink, 2018).

Rationality can be understood in the following ways: 1) Traditional Rationality, which upholds values originating from tradition; 2) Rationality that is supported by behavioural patterns that become beliefs and cultural practices deeply rooted in tradition; 3) Affective Rationality, which leads to a unique emotional connection that cannot be separated from one’s own circle; and 4) Objective Rationality, which relies on reason to choose goals and means of action.

Modernisation TheoryModernisation serves as a vision and context for the primary analysis of humans in a society. Modernization and mentality become commodities that cause change. Strengthening the human soul adds to the primary capital, increasing the local economic production of a community. Modernity produces a culture of science and technology (Kuhn, 2013).

Modernisation, from both an economic and non-economic perspective, reveals increased financial triggers, significant economic change, and public investment, and a lack of capital can cause the problem of underdevelopment. Meanwhile, from a non-economic perspective, it can be seen that the values of faith shape human dynamics. From a non-economic perspective, causing economic growth is based on a relationship of trust with the economy; ethical beliefs give birth to honest capitalist morals and attitudes toward life (Kim and Kwak, 2022).

Physiologically, the will to reason and work hard makes everything perfect according to one’s position in the world; The concept of the need for achievement is a new driving force in facing work, which encourages success and leads to material rewards as an achievement of inner satisfaction. Poverty and underdevelopment of society occur because we do not activate a conducive environment, such that we do not contract the virus needed for achievement (Cooper, 2019).

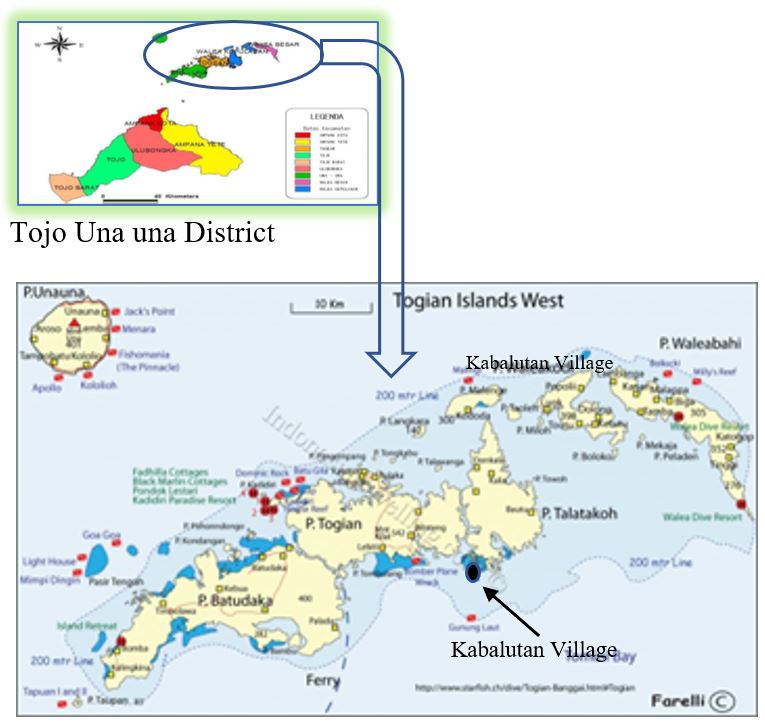

This research was conducted in Tojo Una-Una District, Walea Islands (in the Togean Island Cluster), in one of the villages, Kabalutan Village, Central Sulawesi Province, Indonesia. This village is inhabited by 80% of the Bajo tribe. Kabalutan Village is one of 31 Bajo Settlements in Central Sulawesi. The population of Kabalutan Village is approximately 2,000 people.

The distance between Kabalutan Village and Ampana City (the capital city of Tojo Una-Una) takes two hours by speed boat. The education level of the residents of Kabalutan Village is generally low, with about 70% having completed elementary school and 30% having completed junior high school or high school, with some being dropouts. Kabalutan Village has educational facilities in the form of elementary schools, junior high schools, and high schools, which are far from the main high schools in the sub-district. The main livelihood of the communities is fishing.

Figure 2 shows the condition of Kabalutan Village, about 500m from the edge of the island of Wales. The houses are built above the seawater and the buildings are embedded in limestone on the seabed and supported by large limestone boulders. The low level of the community's economy and education affects their financial ability to prepare decent housing, which makes them seem relatively underdeveloped. With limited knowledge and inherited fishing habits, their work heavily depends on exploring marine products by fishing, including fishing and trawling, as the village’s primary source of income.

A qualitative method with a value engineering approach is used to innovate and apply local values systematically and measurably. The return of Gotong Royong cultural values is related to the construction of houses and construction process activities (Christensen and Ball, 2019). The desired result is the achievement of the efficiency and effectiveness of development by using a Gotong Royong culture that required for ensuring the quality and performance (Hummels, Cruz Restrepo, et al., 2009). The implementation process follows a two-stage approach.

(BPK Representative for Central Sulawesi Province)

Managing and increasing value through value development engineering is an innovation to create a competitive advantage for a product by redefining the Gotong Royong culture through creation and engineering. Value engineering focuses on achieving an optimal balance between new and traditional values oriented towards efficiency in terms of cost, and effectiveness in terms of implementation. This research considers the relationship between agreements, functions and prices to reward a unique Gotong Royong culture with innovative resources to efficiently and effectively construct houses. However, it is important to note that the results of this study cannot be generalised.

The application of value engineering studies is intended to manage and increase the value of physical activity, activities emphasizing efficiency and effectiveness. This relates to cooperation, such as building houses and housing through joint work that does not prioritise over economic values, despite monetary values being needed for the activities. Economic stimulants are intended as building material assistance provided by the government to the community.

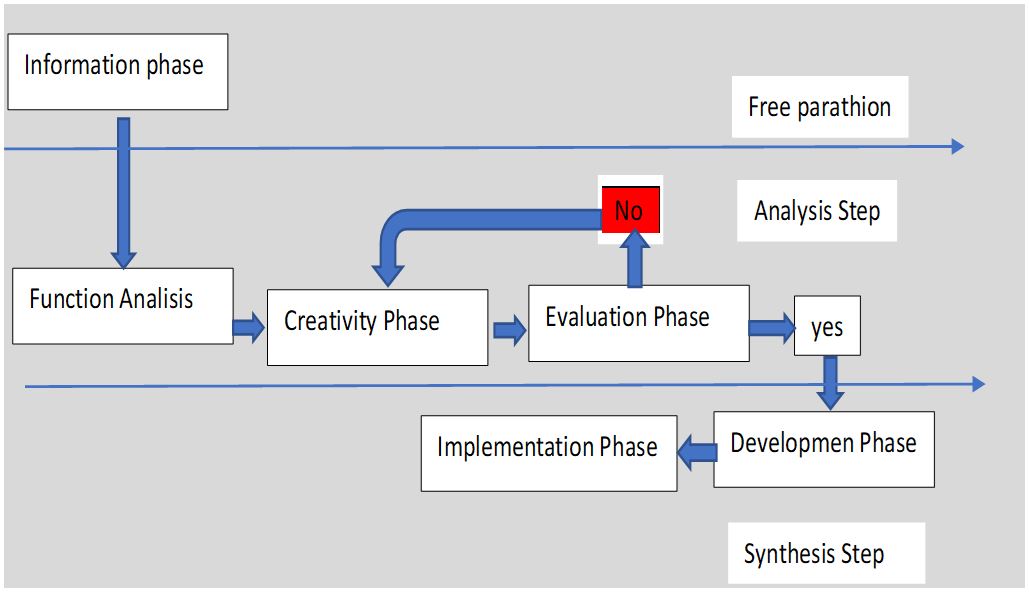

In the past, the construction of houses and housing development were carried out through cooperation. For the Bajo people in Central Sulawesi, this is interpreted as selfless work based on social values. However, the innovations in this study show that the preparation of stimulants is a new form of value, and a form of government involvement in promoting cooperative-based development. The value engineering process consists of five stages: 1) Information phase; 2) Function analysis phase; 3) Creativity phase; 4) Evaluation phase; and 5) Development and Implementation phase. See Figure 3 as follows.

Figure 3 above shows the research process, where stages one and two are the initial stages of research carried out previously. This results in recommendations for the need for innovation and engineering to incorporate new values into the local culture, that which is almost extinct within the Bajo community.

The creative stage is a researcher’s activity to find an overview of the shape of a liveable house for the Bajo community through a focus group discussion (FGD) process. In the evaluation process stage, the evaluation results are discussed again through the FGD forum, and the agreed-upon outcomes are then used in the design process by the research team. The output of this stage includes house designs and form of financing plan. In terms of financing, discussions were held between the research team and the government regarding the funding model, with the conclusion that social spending, rather than capital spending, should be utilised and. is expected to be in the form of grants or government assistance. Therefore, social spending was carried out as government stimulant funds for this research, and the results were subsequently donated to the community.

The findings obtained from the analysis of data and field facts through the stages of research consist of the following: 1) Pre-study Process; 2) Function Analysis; 3) Creativity Stage; 4) Evaluation Stage; 5) Development Stage; and 6) Implementation Stage.

The Pre-study PhaseThe preliminary study results show that there have been changes in people's lives. The indications are revealed in weak social bonds, where people no longer help each other meet their daily needs due to economic factors. As a result, disparities between members of society have become apparent. This is due to unhealthy competition between them. Consumptive habits affect lifestyle, leading to the gradual erosion of the culture of saving and cooperation, which has been replaced with an individualistic culture.

Interesting findings show that the core of the local wisdom of the Bajo community in Kabalutan Village is experiencing degradation. For instance, the traditional practice of mutual assistance, known as "Gotong Royong," which used to be a hallmark and a central pillar of their social life, has now diminished and been replaced by an individualistic culture. This shift has led to the impoverishment of the population. Additionally, housing in the community has developed abnormally due to the inability of new families to prepare their own homes. Instead, they have resorted to attaching their houses to their parents’ homes, resulting in overcrowded and slum-like settlements. This research was conducted when the condition of the community was very apprehensive. Some individuals are unable to meet their daily needs due to low-income levels and the emergence of uncontrolled consumer behaviour. Even those who have access to economic opportunities tend to prioritise secondary needs, such as purchasing satellite dishes, televisions, and tape recorders, while neglecting their primary needs. Addressing this phenomenon requires the involvement of innovation to restore the culture of Gotong Royong in building sustainable homes and housing environments.

Cooperative activities that are usually carried out by the Bajo community, for example, inviting cooperation in the context of kinship, are a legacy of the past. These activities include:

All of the elements above form the foundation of cooperation that demonstrates the existence of the Bajo community. The form of social relations (tolerance) is their trust in others. Currently, the life of the Bajo community in several activities has changed; the culture of Gotong Royong, their trademark, has changed due to economic influences, so this culture has been increasingly marginalised. In building social capital, the Bajo community is guided by four of society’s fundamental values, which are used as a reference. Currently, economic values dominate all activities, diminishing the significance of cooperation. Cooperative efforts in establishing socially-driven settlements have been replaced by paid services, as all activities are assigned an economic value and require monetary costs. This fact shows that payments and houses owned are regarded as financial products of the community, rather than outcomes of communal spirit.

Capitalist culture influences activities tied to monetary transactions. Constructing houses or settlements, which were previously undertaken through cooperation, has now become an economic endeavour, devoid of the social values that characterise the Bajo community. Economic activity no longer creates social space, but revolves solely around financial activities and their supporting elements. Consequently, the sea is perceived primarily as a space for earning income and sustaining livelihoods, rather than a means to meet communal needs.

The Bajo people now spend more time on land or at home than at sea, indicating a shift in cultural values within the society. These differences can be attributed to interactions between the Bajo tribe and neighbouring mainland tribes, particularly through intermarriage with individuals accustomed to modern culture, which has influenced the traditional lifestyle of the Bajo tribe.

Function Analysis PhasePreliminary information analysis shows that the habit of cooperation possessed by the Bajo community has experienced significant degradation over time. As a result, cooperation activities in the Bajo community, such as in Kabalutan Village, have become very rare, with most of these activities now being paid in nature. Only specific actions, such as wedding activities and congratulations, are carried out through cooperation.

The decline in trust in the traditional leaders of the Bajo community has led to the loss of influence of the Gotong Royong culture. On the contrary, economic power has scattered the Bajo people and brought them into contact with mainland people who have different characteristics from the Bajo people. The innovation of the Gotong Royong culture is believed to strengthen the Bajo community’s commitment to the idea that the sea is their home and cooperation is their trademark.

Changes in the beliefs of the Bajo tribe from dynamism to Islam have also resulted in a decline in productive ritual activities, which are now being abandoned. Efforts to restore culture and strengthen cooperation are expected to reintroduce various forms of rituals that were previously inherent in the Bajo community, serving as generators of enthusiasm for building the social capital of the Bajo community. The aim is to revive ritual practices that strengthen friendship ties. The influence of global culture, with its capitalist elements, is believed to shape joint activities in a way that incorporates positive traditions into ancestral cultural rites, symbolized by the Bajo tribe. This is intended to rebuild social solidarity among the Bajo community.

The situation for the Bajo tribe is worrying because those engaged in marine product activities face the obstacle of storms at sea. Sometimes, because these conditions do not allow them to generate income and their journey is hampered from returning home, misunderstandings can occur among the Bajo tribe. However, these circumstances serve as a common thread or bond that connects them. The members of the Bajo tribe have the understanding that in the face of a storm at sea, they share a close bond between them, utilise every place they visit to avoid disaster, and they accept one another as brothers. This tradition is still highly respected by the Bajo tribe to this day. It forms the basis for efforts to restore the culture of Gotong Royong, with various additions. For example, the economic aspect is one of the values within the Gotong Royong culture.

Creativity PhaseEfforts to restore the Gotong Royong culture require a process of value engineering innovation, namely returning old values to their present conditions so that Gotong Royong is enriched according to the current context so that the existing Bajo community can accept it (Van der Linden, Dong, et al., 2019). The stages of the design and build activities begin with the creation of the house and the preparation for the implementation phase, which refers to the principles and cultural values of Gotong Royong in housing and housing construction activities. The government supports these activities through the provision of stimulant funds. This is done by creating stimulant funds from government programs that support applying the principle of Gotong Royong. To implement the culture of cooperation in the Bajo community, a method is needed. The design of research activities aimed at restoring the values of Gotong Royong among the Bajo community is as follows:

The results of the selection process determined that 30 families expressed their willingness to be involved in this research program. The selected participants formed five groups, each consisting of six families. Each group prepared a work plan schedule that does not interfere with their fishing activities. A stimulus fund of Rp 10 million will be distributed to each group, with a target of procuring 1,400 poles within one month.

The next stage involves a stimulus fund of Rp twenty million with a target for building a connecting road, within a target completion time of one month. In this phase, some participants expressed their inability to continue and withdrew from the activity. As a result, the number from 30 housing units to the targeted 20 housing units, based on the initial agreement that those who withdrew would not be compensated for their past work.

A stimulus fund of Rp 40 million is allocated for the next stage, which is used to complete the floor and wall frames using local materials such as nipa palm leaves for the roof, planks 1 meter high for the walls, and nipa palm leaves for the walls above. This phase takes two months.

An agreed stimulus fund of Rp eighty million is used for installing the building's walls, roofs, and floors, with a target completion time of one month.

The stimulus fund of Rp 80 million is also used to install doors and windows and complete various finishing works, including making family latrines. Therefore, the total stimulus fund used amounts to Rp. 230 million, fulfilling housing and settlement development activities, which include 20 housing units and a 230-metre-long, 2.4-metre-wide road. The remaining funds serve as stimulus funds for the groups of mothers to support family activities and increase family income.

The government provides assistance for the stimulus liability, with a settlement date set for November of the current year. The financial liability obligation expires on December 15th.

Evaluation PhaseThe draft plan evaluation indicates that the implementation of Bajo housing and housing development planning program in Kabalutan Village involves the consensus of all stakeholders, agreeing on several steps to implement the concept of Gotong Royong. In order to revive the culture of Gotong Royong, various stages of the program have been agreed upon, with a foundation based on agreements among all stakeholders, including elements from the central government, community leaders, the Village government, as well as implementing groups and beneficiaries, which consist of women's groups as financial managers and men's groups as job executors (Vezzoli, Ceschin, et al., 2015).

The evaluation further confirms that the program agreement is deemed appropriate for implementation, as the cultural values of Gotong Royong have been incorporated into every activity, particularly in house construction activities, where each family is granted equal rights. The actions carried out in these activities do not require monetary wages and are open to participation from relatives, thus accelerating the completion process. The stimulant funds provided are not considered as capital, but rather as incentives in the form of material assistance, ensuring the smooth progress of the activities.

All program implementations, which were jointly prepared through FGDs (Focus Group Discussions), have been executed according to plan and feasibility, resulting in satisfaction among the beneficiaries. No objections were raised by any of the stakeholders regarding the achieved outcomes.

Based on the budget calculations, it is determined that each house requires Rp. Forty-five million rupiahs, and the collective effort to construct 20 housing units requires Rp. Two hundred and thirty-five million, equivalent to 11.65 million Rp per unit. This demonstrates an efficiency level of 300%, and the implementation timeline is deemed sufficient as it does not interfere with people's income.

Development phaseImplementing the work program nurtures a culture of cooperation in the Bajo community. The process begins with socializing the program to all stakeholders in Kabalutan Village, involving the community, government, and local leaders. Through a series of Focus Group Discussion (FGD) activities, a development work program is formulated, and an agreement is reached on the mechanisms of program activities.

The implementation of the program development plan starts by selecting participants who are willing to engage in this collaborative work as a demonstration of the cooperative culture. After selecting several participants, it is agreed that 30 families will be involved.

The first step is to establish an agreement among the participating families and with the government, specifically the Centre for Settlement Technology Development in Eastern Indonesia, which serves as the provider of stimulant funds for the activities.

Figure 4 illustrates the residents' engagement and discussion on the stages of building houses and housing through mutual cooperation. The meeting takes place in one of the residents' homes, where deputy facilitators and family members, including husbands and wives, participate. The next step involves the transfer of the stimulant funds into a joint account, creating a savings account. However, the disbursement of these funds is subject to fulfilling all the requirements, overseen by a women's group composed of the wives of participating husbands within the family groups.

Implementation PhaseImplementation of the first phase began with the disbursement of a stimulant fund of 10 million Rp within one month to procure 1,400 wooden poles. In this phase, the group faced obstacles as ten families decided to withdraw from the program due to unmet expectations. Therefore, the group needed to address their stance towards these ten families who withdrew. . During a group meeting, it was decided that the remaining 20 families would assume responsibility and continue overseeing the activities until all the required pillars (1,400 sticks) were attained.

Figure 5a depicts the transportation of logs for house construction and the road connecting the homes. Figure 5b showcases the poles that have been inserted into the sea to support the road and the designated construction area. It also demonstrates the handover of stimulant funds from the women to the five group leaders, along with an explanation of the fund utilization and the associated targets. Once the distribution of further stimulant funds has been evaluated and the targets have been met, the second stimulant fund will be disbursed.

Stimulant funds are held in the account of the mother's group, and their disbursement requires approval from the research team leader, who serves as the team facilitator and oversees collaborative activities. Prior to commencing work, deliberations were conducted and community leaders from Kabalutan Village were invited. The activities began with ritual ceremonies for house construction, seeking permission from village leaders and traditional leaders to carry out the project. After gathering the 1,400 sticks, a ritual was performed at the construction site to seek permission from the ruler of the sea.

The second phase of the development plan involves installing the poles for house construction and constructing roads above the water level using a stimulant fund of Rp. 20 million. However, the implementation of this activity faced constraints related to the chosen method, which involved using wooden poles and concrete blocks as a beater to secure them in the sea. As this method proved ineffective, the group leaders discussed alternative approaches. Ultimately, they decided to sharpen the ends of the poles and embed them into the seabed, a method often used and inherited by their ancestors. Additionally, two canoes were utilised to flank the logs/sticks, allowing them to stand upright. Wooden bars were added on top of the logs, and two people acted as weights. The bars were rotated until the poles were embedded to a satisfactory depth.

Figures 6a, 6b, 6c, and 6d depict a series of activities, including the installation of piles using a simple propulsion device and the successful establishment of all the banks using local wisdom techniques.

The subsequent stage involves installing the building frame using a stimulant fund of Rp. 40 million, and that is not justified in a culture of cooperation which is a common goal.

The images above illustrate the implementation process, starting from pillar installation to the construction of the frame structure, followed by the installation of walls, floors, and low roofs. The installation of doors and windows will proceed as planned, although some challenges have arisen due to limited working hours during the day as participants need to return from the sea. To address this, those who return late utilise the night hours to continue their work, resulting in collaboration between multiple groups and families to overcome time constraints. Consequently, the spirit of gotong royong is increasingly evident and practiced.

Figure 7 shows the ritual process carried out to complete the housing construction framework, which has reached 20 units of buildings along with connecting roads, which was carried out by the Bajo community and was supported by stimulant funds provided by the Centre for Research and Development of Public Housing Technology in the Eastern Region. The objective of this initiative was to ensure the plan would run smoothly, as each family received assistance during the construction process. With the additional stimulant funds, they reached a consensus to reduce their time spent at sea and focus on getting the house built to completion. This approach allowed them to meet their basic needs using the surplus stimulant funds that were provided.

Source: Research documents, 2019

Figure 8 above depicts one of the processes of distributing stimulant funds, wherein each group and family must provide a signature as a testament to their acceptance of the funds. These stimulant funds come from government funds and, therefore, require proper accounting procedures in line with budgetary regulations.

At the end of construction, it was agreed that the remaining 65 million RP of stimulant funds would serve as working capital for the women's group to establish a business managed by the mother group. Additionally, these funds would serve as a form of compensation for their efforts in mobilizing the stimulant funds for this project.

DiscussionImplementing cooperation for the Bajo community that is rational and acceptable to them is in line with the proposed pragmatic thinking put forward by Christensen and Ball (2019). A practical review, integrated with fundamental processes in human action and experience, is conducted to examine local values and priorities for collaborative activities. This approach contributes to the functionality of work-related aspects in sustainable development programs. Moreover, the designed program can be practically implemented to provide guidance in the design process and facilitate understanding and management by involving diverse interest groups.

To help understand and manage the design process (Vezzoli, Ceschin, et al., 2015), this activity allows the development of a work culture, as a form of adaptation to current conditions. It is based on mutual trust and mutual respect, and a rational understanding of the aim to return the culture of Gotong Royong to the life of the Bajo community.

Furthermore, the culture of Gotong Royong represents an effort to revive the life of the Bajo people based on rationality so that they can be accepted back into society, agreed by the community (Christensen and Ball, 2019). The culture of cooperation built and planned is compatible with pragmatic theories of truth and rationality, integration and fundamental processes in action, as well as human experience as a test of public values and priorities for action, which has an impact on all program participants progressing well and successfully.

Other contributions have been made to the usefulness of sustainable development. At a practical level, concepts are operationalised to inform and guide design and help understand the design process in building systems following previous methods, such as the Gotong Royong culture system (Vezzoli, Ceschin, et al., 2015). These work in the contemporary culture of cooperation.

The description of the house's structure and shape is considered a manifestation of the community’s cultural values by its adherents. Visible from the house is a shelter for humans in the face of climate change, weather (hot, cold, rain, and wind), and animal attacks. Furthermore, the house is also referred to as a place to live because it functions as a place to rest, a place to build a family, a place to work, and a symbol of social status (Kempenaar and van den Brink, 2018). The existence of a house, in the understanding of the Bajo people, was originally a stopover place when a storm hit. However, in its development, the house is a place to live that protects family and neighbours so that social capital is formed in society, which in turn creates a culture of cooperation in the life of the Bajo community; this is in line with the opinion of Rapoport (1969).Human behaviour patterns vary depending on the location and the stimuli they encounter. With the development of science and technology today, there are opportunities for traditional societies to connect with various aspects, such as social, cultural, religious, and physical aspects, while human behaviour patterns vary depending on the location and the stimulus it receives. With the development of science and technology today, there are opportunities for traditional societies to connect with these different aspects and adapt accordingly.

The theory of social change related to traditional society shows that community cultural values play an essential role in forming community groups that can adapt to their environment. Experimental efforts carried out on the current Bajo community by applying the modified and redefined values in this study show that fundamental values, namely the values that belong to the Bajo community group, can be maintained by adding new meanings to old values for today's society. For example, attempts at reinterpretation are made because old values are not adapted to changing organizational needs, knowledge, and technology. In this case, it is impossible to carry out efforts to preserve culture even though it is believed that there will be a decline in value, even the extinction of old values, due to not being able to withstand the onslaught of the times. New agreements that develop in society must be adapted to environmental developments and the latest demands.

Efforts to do value engineering through the meaning of old values provide new energy to old values so that they can compete with the emergence of new values. For example, the value of Gotong Royong, which is only oriented towards the formation of social capital, will be degraded if it is unable to accommodate economic needs that produce prosperity. To adjust the values, including economic prosperity, to become human needs today, it is necessary to intervene in social capital as a past orientation so that social capital is not only aimed at building social networks and brotherhood but also considers financial aspects, which are very important in the current era. Thus, social capital and economic capital need to be integrated into the life of the Bajo people.

Social capital cannot stand alone in Bajo society but requires financial value as its reinforcement. The culture of Gotong Royong must be developed by combining economic and social welfare. Therefore, for the values of cooperation to be sustainable, it is necessary to adjust the meaning of existing values with the development of science and technology to strengthen cooperation as the basis for forming community settlements, as it happened in the Bajo community in Kabalutan. Public ignorance about the development of Gotong Royong values is a sign of Gotong Royong culture degradation in society. If left unchecked, the culture of cooperation in an organization can only be seen as an activity that compromises other activities. The culture of Gotong Royong no longer characterizes specific communities (Bajo).

The conclusion of its implementation is as follows. The performance of the Mutual Cooperation Cultural Innovation Programme in the Bajo community has positively impacted activities, and collaboration between programme participants has had an extraordinary effect on efficiency and effectiveness. This innovation builds mutual trust and respect among community members and positions them in society according to their respective roles; for example, the government, community leaders, and society as a whole have their respective roles in preserving the culture of Gotong Royong. Based on the pilot programme results, the Gotong Royong programme creates openness in society and facilitates continuous communication regarding any changes that occur, ensuring the survival of this culture as new meanings develop. Communication must be continuously built to maintain the values previously associated with the culture of Gotong Royong and enrich them with new values that align with the needs of community development.

The results achieved were in the form of efficiency in development financing, with an efficiency rate of 300%; effectiveness was also achieved as the programme did not interfere with the community’s main activities. Several notable findings emerged, including the discovery of a new material in the form of a type of wood that was previously not documented in the forestry dictionary. The effective method of setting up piles in the sea is derived from local wisdom.

The author declares that there is no potential conflict of interest regarding the publication of the paper.

This research is the beginning of an effort to restore the values of Gotong Royong through an innovation process; in this study, it is suggested to continue with other cases with different backgrounds to find patterns that can be used as a theory about Mutual Cooperation Culture in the future. The Research Team's contribution was in the form of efforts to facilitate activities to meet targets.

The Stimulant Fund is a social fund provided by the government solely for this program, and the researcher does not receive compensation for the research being carried out independently. The author said that all participants in the research subject agreed and expressed their will without being paid.