2023 Volume 11 Issue 3 Pages 244-265

2023 Volume 11 Issue 3 Pages 244-265

Population displacement theory concerns settlements as a form of sociocultural action rather than a passive reaction to a sudden influx of refugees. The literature suggests that formal camp planning affects the efficiency of services, infrastructure, safety, and the health of refugees. The present study explains spatial patterns at the Zaatari Syrian Refugee Camp in North Jordan, Al-Mafraq, and the shifted emerging patterns and their influence on the efficiency of the settlement. The objectives of the study are first, to identify the influence of spatial settlement patterns on mobilizers’ reachability, which reflects the efficiency of the settlement; and second, to identify the influence of spatial shifts on the efficiency of the camp. Face-to-face interviews with camp mobilizers explained the shifted settlement patterns and their influence on mobilizers’ reachability to the residents. A cluster-stratified random sample was used to collect quantitative data through a structured questionnaire. Next, linear logistic regression and one-way analysis of variance tests were utilized to test the influence of the emerging settlement patterns on the total efficiency of the settlement. Spatial settlement patterns specifically affect accessibility and communication, while infrastructure and safety are unaffected. To increase accessibility to services and efficiency of communication between refugees and mobilizers, planners should consider emerging sociocultural patterns.

With the escalation of the Syrian crisis in 2011, expanding numbers of Syrians have been seeking refuge in neighboring countries, including Jordan. The Zaatari Camp emerged in Al-Mafraq as a quick response to the sudden influx of refugees to Jordan. Statistics show that 618,615 Syrians sought asylum in 2014. However, only 20% of them were staying at the camp, as the majority moved to Jordanian urban-based communities, with some of them leaving legally but the majority illegally (Hall, 2013; Bonnin, 2012; UNHCR, 2014). Zaatari Camp became home to almost 81,000 Syrian refugees (UNHCR, 2022).

Settlements and resource management are highly influenced by the spatial context. Planning a refugee camp usually ignores sociocultural specificity (Alshawawreh et al., 2017; Corsellis and Vitale, 2005; Scudder and Colson, 1982; Shami, 1993; Woods, 1982). Articulating the social structure of displaced communities has a key role in weaving the urban spatial pattern (Dalal, 2022; Corsellis and Vitale, 2005; Rapoport, 1969). The significance of this study stems from explaining the emerging settlement patterns of Zaatari Camp within its sociocultural context and how the pattern affects the efficiency of the settlement regarding mobilizers’ reachability to settlers compared to the standardized camp patterns.

Since the foundation of Zaatari Camp, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) planners adjusted the spatial pattern on a grid base without consideration for refugees’ sociocultural background (Alshawawreh et a., 2017). The grid plan is the easiest and fastest spatial pattern to implement, especially in the cases of humanitarian disasters, when quick and immediate actions are needed in the middle of chaos. Camp planners utilize the grid plan for security reasons as well, to avoid clustered plans that would be controlled by influential groups of refugees (Bonnin, 2012; Corsellis and Vitale, 2005). However, refugees shifted the grid pattern and created clustered social spaces (Al-Homoud and Samarah, 2022; Dalal, 2022; Dalal, 2020; Dalal et al., 2018). The argument made here is that what are those emerging spatial settlement patterns, and whether the grid versus the shifted-from-grid patterns have influences on the efficiency of the camp reflected by mobilizers’ reachability to the settlers.

The specific objectives of the study include:

1. Identifying the influence of spatial settlement patterns on mobilizers’ reachability, which reflects the efficiency of the settlement,

2. Describing the influence of the spatial shifts on the efficiency of the camp, and

3. Providing guidelines for future refugee camps.

The study is one of the few scientific works examining the sociocultural context of the Zaatari Camp.

This research is the first to consider the connection between Syrian refugees’ pre-settlement cultural experience and morphology, which strongly counters the standardized camp typology. Refugees created their own layout reverting to their original home experience. Moreover, this work plays a key role in redirecting the physical planning context, highlighting planning gaps that are related to Syrian refugees’ unmet sociocultural needs. This effort will allow camp officials and mobilizers to enhance the performance of the settlement in Jordan.

After a review of the relevant published literature, quantitative data were collected and analyzed. The research method elaborated answers to the research questions raised, thereby allowing for a better understanding of the phenomena concerning the emerging settlement patterns and their influence on the efficiency of the settlement.

The hypotheses of the study include (1) The efficiency of the settlement is affected by settlement patterns at Zaatari Camp, and (2) The efficiency of the settlement is defined in terms of physical attributes, such as accessibility and infrastructure, and sociocultural attributes, including safety and communication.

A structured questionnaire consisting of closed-ended questions was administered, and a stratified cluster sampling technique was used to select the sample. Stratification was implemented to represent each cluster in the assigned six districts. Four subjects were selected from each of the (117) clusters in the six investigated districts.

The review mainly addresses works related to population displacement theory, informal and formal patterns of displacement, planning issues, physical layout, and sociocultural understanding, in addition to selected case studies in Jordan.

Population displacement theoryPopulation displacement was initially introduced by a group of researchers as a collective change of location from the place of origin by superior forces directly or indirectly. It could be permanent or temporary, voluntary, or involuntary, and can be done individually or in groups. Displacers could be tied together sometimes as kin, communities on notions of ethnicity or politics, or through shared cultural heritage (Hansen and Butzer, 1968; Shami, 1993; UNHCR, 2002). Displacement theories mostly concern the causes and effects (Cernea and McDowell, 2000; Shami, 1993; Woods; 1982). Agents of displacement are mainly development projects, war or political upheaval, and natural disasters. Whatever the reason behind displacement is, similar consequences befall refugees (Cernea and McDowell, 2000; Loizos, 1981; Olson, 1979; Shami, 1993; Shami, 2009).

Protection and security are the principal reasons behind political population displacement. Therefore, safety and psychological needs are fundamental for refugees. In such cases, refugees seek other sources of protection, within or across their homeland borders (Bajpai, 2000; NRC, 2009; Barutciski, 2012). Such insecurity continuously informs the resettlement, and causes some changes in refugees’ community patterns and may generate difficulties in adapting to the new altered situation (NRC, 2009; Corsellis and Vitale, 2005; Shami, 1993).

Population displacement has multi-dimensional consequences, affecting the socioeconomic structure and the physical environment of refugees in the new settlement. Such affects include the socio-economic structure and the physical environment for refugees in the new settlement (Corsellis and Vitale, 2005; Scudder and Colson, 1982). Impacts are different on men, women, and children. The more commitment there is before displacement, the more the grief reaction is the socio-economic consequences affect not merely refugees, but also the hosting society (Saarinen, 1976; Scudder and Colson, 1982).

Social impact includes fragmenting families and communities. Physical planning can influence how refugees reconstruct and develop their communities and reinforce their traditions to support each other (Corsellis and Vitale, 2005; UNHCR, 2002). These factors influence the adaptation of refugees to their new location (Corsellis and Vitale, 2005; Shami, 1993). The following section will show potential physical planning patterns.

Patterns of displacementThe main goal of transitional settlements is to provide a secure, healthy living environment, privacy, and dignity to groups, families, and individuals settled within them. Transitional settlements refer to the camps provided for refugees. They are communities of covered living spaces that may range from emergency responses to durable solutions. High-density settlements with large populations are the worst possible alternative for refugees, although refugees might not have the freedom of choice because of the decisions made by the host country, or because of a lack of alternatives (Corsellis and Vitale, 2005; UNHCR, 2000). Refugee camps generally have two major patterns, including an informal category known as “dispersed settlements,” and a planned formal pattern known as “grouped settlements” (Corsellis and Vitale, 2005; Scudder and Colson, 1982; UNHCR, 2000).

Informal Patterns: Displaced people tend to spontaneously choose dispersed settlements to maintain their independence and sustain themselves because they are associated with lower security risks. However, such settlements are more prone to tensions with the host community. Refugees who choose to live in dispersed settlements have the following three alternatives: (1) Dispersed in host families: refugees live with local families or buy land/properties. (2) Dispersed in rural self-settlement: refugees settle on lands owned by groups of locals in rural areas. (3) Dispersed in urban self-settlement: where refugees informally settle in urban areas or occupy unclaimed lands. Planned/Formal Patterns: Formal planned settlements have three types, known as grouped settlements: (1) Grouped in collective centers: Refugees settle in preexisting buildings including community centers, town halls, or hotels. (2) Grouped in self-settled camps: Camps are not managed by any agency. (3) Grouped in planned camps: Refugees stay on site where they are provided with help and services by humanitarian agencies (Corsellis and Vitale, 2005). This last pattern is the adopted pattern for Za’atari Camp, the case of the present research. This is the case, because UNHCR considers planned settlements the last resort as it encourages dependency and is easier to retreat to than the alternatives. Durable solutions are more challenging to achieve for the refugee population. Consequently, vulnerabilities could be increased due to internal and external security concerns (Bonnin, 2012; Corsellis and Vitale, 2005).

Socio-cultural understanding: Emerging patterns versus standardized planningResearchers claim that the main phase of adaptation is when relocated groups attempt to recreate the community they lost. Adaptation occurs through the revival of their rituals and life routines, to cling to their past as a form of nostalgia (Al-Homoud and Samarah, 2022; Dalal, 2022; Dalal, 2020; Shami, 1993). Throughout the process of displacement, families undergo structural changes such as dispersal, fission or fusion, and all factors that might affect individuals’ identity and group solidarity (Scudder and Colson, 1982; Shami, 1993; Shami, 2009). In that displaced populations usually settle as communities, social ties including families and kinship play the greatest role in the adaptation to the new circumstances. Despite the temporality of the camps, the dynamics between settlers and their settlement will take part in shaping behaviors, spatial configurations, and the way the settlement functions (Al-Homoud and Samarah, 2022; Dalal, 2022; Dalal et al., 2018; Corsellis and Vitale, 2005; Davis, 1978; Fried, 1963; Pryor, 1975; Scudder and Colson, 1982; Shami, 1993).

Moreover, desires, motivations, and refugees’ feelings affect their behavior and the morphological spatial patterns. Consequently, the physical milieu and its performance are a result of the interplay between the planning patterns set by the responsible planners and the shifts made spontaneously by the settlers (Al-Homoud and Samarah, 2022; Dalal, 2022; Dalal et al., 2018; Corsellis and Vitale, 2005; Linn, 1983; Rapoport, 1969). Moreover, the settlements’ spatial configuration may be a device for social defense. Therefore, the types of settlements can result from the behavioral patterns of the settlers, which are a result of their way of life (Al-Homoud and Samarah, 2022; Dalal, 2022; Dalal et al., 2018; Corsellis and Vitale, 2005; Flanagan, 1990; Rapoport, 1969).

As time goes by, refugees apply changes to adjust their settlement in a way that suits their sociocultural identity. Refugees make changes to their dwellings and the settlement overall to meet the needs of their families and their lifestyles (Al-Homoud and Samarah, 2022; Dalal, 2022; Dalal et al., 2018; Alshawawreh et a., 2017; Al-Homoud, 2003; Corsellis and Vitale, 2005; Fathy, 1973; Lapidus, 1969; Linn, 1983; Rapoport, 1969). Although the social and cultural values take over all other forces behind adjusting the spatial arrangement, there are other additional forces including age, religion, climate, ceremonial beliefs, defense, and satisfaction (Al-Homoud and Samarah, 2022; Corsellis and Vitale, 2005; Linn, 1983; Rapoport, 1969). If the traditions are alive, the shared accepted image of life continues to operate. For instance, if the culture dictates that women should live within household compounds, then latrines and the shelter design should meet these traditions. Furthermore, shelter patterns for single women should respect the culture by providing designated areas for single women and their dependents (Al-Homoud and Samarah, 2022; Alshawawreh et a., 2017; Anderson, 1994; Corsellis and Vitale, 2005; Rapoport, 1969).

Specialized researchers agree that refugee camp planning must be accomplished on three levels. First, the strategic level by which transitional settlements are managed on a large scale (regional/national level), mainly dealing with shelters and the general needs of refugees. Second, the program level is concerned with the needs of a specific group of refugees. Third, the project level involves managing the activities of a camp within the physical plan (Corsellis and Vitale, 2005).

Well-planned settlements have positive impacts beyond the provision of shelter, for they help in strengthening physical protection and enhancing livelihoods by managing natural resources and minimizing the spread of disease. However, refugee camps are highly influenced by the provided protection and security facilities, gender, age, and vulnerable groups of refugees (Corsellis and Vitale, 2005; Project, 2004; UNHCR, 1967; UNHCR, 2000). Poor planning of refugee camps might increase the vulnerability of some minorities such as ethnic and elderly people groups.

When attempting to provide protected and secure settlements, fundamental strategies should be considered: (1) Reduce vulnerability and exposure to threats, (2) Assure the visibility of individuals and groups to protection forces and witnesses, and (3) Provide refugees with quality and security enforcement systems of justice. Segregating groups is also essential to minimize the chances for communication, particularly when tensions are more likely to surface (Corsellis and Vitale, 2005; UNHCR, 2002).

Successful refugee camp planning should meet the cultural expectations of refugees to avoid any social disruption. Likewise, conflicts between or within families, clans, and ethnic groups can be avoided or at least reduced (Anderson, 1994; Corsellis and Vitale, 2005). During the influx of refugees, it is preferred that displaced families live adjacent to people whom they know inside the camp to help them rebuild the sense of their lost community. These familiar groupings are not always possible because people arrive over an extended period. However, consolidation of their community is possible when families change locations within the settlement to reside near people whom they know (Cernea and McDowell, 2000; Corsellis and Vitale, 2005). On the other hand, basing the planning process of the camp around the family (one household) leaves no space for individuals who are not part of a family structure and are left without the protection of the community (Cernea and McDowell, 2000; Corsellis and Vitale, 2005; Shami 1993).

The camps’ spatial patterns have social, financial, and environmental influences on refugees; they can increase the efficiency of the provided services and infrastructure, and donations delivery (UNHCR, 1967; UNHCR, 2000; Project, 2004; Corsellis and Vitale, 2005). Well-planned camps help refugees at the socio-economic, as individuals and communities, to manage their lives by regulating the provision of needed resources such as food, water, clothing, and shelter (Bonnin, 2012; Corsellis and Vitale, 2005). Refugees create a concentrated consumption to natural resources. In addition, tensions and conflicts can arise between refugees and the local community. Another concern is the risk of de-skilling due to the dependency and overreliance on aid agencies and few competitive work opportunities, and a lack of certainty about the future and the period of stay (Corsellis and Vitale, 2005; UNHCR, 2002).

When considering refugee camp planning, two key approaches are followed, namely the grid and the cluster approaches. In the widely adopted grid approach, a grid of roads is set out Communities and administrative and communal facilities are placed in the spaces between roads. The grid is simple to design and mark out, creating repetitive patterns of rows and plots where shelters are located. The layout provides equal access to all plots. In the cluster planning approach, major road infrastructure is planned like tree branches with the roads going from central areas used for communal facilities. Hierarchy in roads exists and varied road sizes can be introduced depending on the amount of use. This approach aims to form decentralized groups of communities, where shelters are grouped to easily define social units. Cluster planning is preferred because it supports the social communities by introducing private areas, encourages mutual communal activities such as water collection and cooking, and reinforces a social hierarchy that supports the acceptance of extension programs (Corsellis and Vitale, 2005; UNHCR 2002). Land lots in refugee camps are generally identical in size, usually only residential uses are spatially planned at the block level (UNHCR, 1967; UNHCR, 2000; Project, 2004; Corsellis and Vitale, 2005).

Most of all, Physical planning includes provision of spaces for market and commercial facilities, medical services, feeding centers, animal husbandry, food from agriculture, food and nonfood distribution centers, education, recreation, child-friendly spaces, religious and ritual facilities, and cemeteries and mourning areas (Anderson, 1994; Bonnin, 2012; Corsellis and Vitale, 2005; Linn, 1983). Camp planning should meet the minimum accessibility standards to the fundamental livelihood means and services that refugees require. Settlements should be organized to facilitate the process of distribution of food, nonfood items, and informative fliers (Bonnin, 2012; Corsellis and Vitale, 2005).

The minimum required facilities for refugee camps are site layouts, camps sub-divided sectors, blocks, and standards for provided services. Refugees require flattened roads and paths without obstacles, surface water drainage, water points, sanitation, garbage disposal, and communal washing facilities. Additionally, having enough lighting in camps is crucial, particularly in dark areas, to provide a safe and secure environment. Furthermore, information points are highly recommended so refugees can get the information they need and raise their concerns regarding the provided services and facilities (Anderson, 1994; Bonnin, 2012; Corsellis and Vitale, 2005; Linn, 1983).

The quantitative design attempts to describe the hypotheses and constructs of the study, including the variables, instruments, population of the study, and sampling techniques and procedures. The quantitative study consisted of a survey utilizing a close-ended structured questionnaire that was administered to a random stratified cluster sample of refugees.

Research Design: The study tested the impact of settlement patterns on the efficiency of the settlement. After reviewing relevant literature, a structured questionnaire was constructed, and a survey design was utilized to collect the needed data from subjects living at the Zaatari camp.

Hypotheses of the Study: The efficiency of the settlement is affected by the settlement patterns at the Zaatari Camp. In particular, the settlement’s efficiency is defined in terms of its physical attributes, including accessibility and infrastructure, and sociocultural attributes, such as safety and communication. The sub-hypotheses in this study are listed below:

1.a. Efficiency of accessibility to services in the settlement is affected by settlement patterns at the Zaatari Camp. The efficiency of accessibility to services includes schools, education facilities for women, recreation, medical centers, kitchens, and latrines.

1.b. Efficiency of infrastructure is affected by the settlement patterns at the Zaatari Camp. The efficiency of infrastructure includes indoor and outdoor lighting, walking paths, sewage, garbage disposal, and cleaning maintenance.

1.c. Sense of safety within the settlement is affected by settlement patterns at the Zaatari Camp. “Sense of safety” includes protection of self and family, protection of self and family with the help of neighbors, protection of self and family with the help of relatives, protection of belongings, protection of belongings with the help of neighbors, and protection of belongings with the help of relatives.

1.d. Efficiency of communication is affected by settlement patterns at the Zaatari Camp. The efficiency of communication includes obtaining information, getting information updates, retrieving information from a place, getting information from a contact, raising concerns in a place, raising concerns to a contact, and raising concerns to mobilizers.

Variables of the studyIndependent Variable: Settlement patterns at Zaatari Camp serve as the independent variable. The definition of settlement patterns is the arrangement of shelters and outdoor spaces within the settlement. Clusters with emerging central spaces were described as shifting due to potential social demand. The clusters were measured using a nominal measure: (1) linear grid, (2) shifted-from-grid. Data were collected through the following question: The type of cluster pattern, that is, (1) linear grid, and (2) shifted-from-grid.

Dependent Variables: Efficiency of the settlement was the dependent variable, defined by refugees’ ability to obtain basic needs with minimum wasted resources and effort.

Efficiency was measured through the following sub-variables: accessibility to services, provided infrastructure, safety, and communication within the settlement. These variables were measured on a five-point Likert scale: (1) strongly disagree, (2) disagree, (3) not sure, (4) agree, (5) strongly agree, and (0) not applicable.

a. Accessibility to services: This variable is defined by facilitated access to the provided services within the cluster, including schools, education facilities for women, medical centers, latrines, kitchens, water and sanitation, and recreation. Data were collected through the following questions: Express your satisfaction with the following statements: My children have easy access in my cluster to school, education facilities for Women, recreation, medical services, kitchens, and latrine.

b. Provided Infrastructure: This variable is the provision of basic structures and facilities the community needs to operate, including indoor and outdoor lighting, walking paths, sewage, garbage disposal, and cleaning maintenance. Data were collected through the following questions: “Express your satisfaction with the following statements: My shelter is provided with the needed: indoor lighting, outdoor lighting, circulation, walkable paths, sewage infrastructure, garbage disposal, and cleaning maintenance.”

c. Safety: The sense of protection from risks to selves and belongings is “safety.” Data were collected through the following questions: “Express your satisfaction with the following statements: Protection of self and family, and protection of belongings.”

d. Communication within the settlement: This variable is defined by the facilitated exchange of information between refugees and camp mobilizers or service providers regarding obtaining information and raising concerns to mobilizers. The variable was measured using a five Point-Likert scale: (1) strongly disagree, (2) disagree, (3) not sure, (4) agree, (5) strongly agree, and (0) not applicable. Data were collected through the following questions: “Express your satisfaction with the following statements: Getting Information and Raising Concerns.”

Confounding Variables: Potential confounders include the personal information of subjects who might influence the relationships of the study including gender, city of origin, length of stay at the camp, number of households in the cluster, number of children in the cluster, number of females, age, education level, and past housing experience. Data were collected and measured as follows:

1. Gender: (1) Male, (2) Female

2. City of Origin: City of Origin: (1) Dara’a, (2) Homs, (3) Other.

3. Length of stay at the camp: (1) less than one month, (2) one month to less than six months, (3) six months to one year, and (4) more than one year.

4. Number of households in the cluster: Number of households in the cluster.

5. Number of children in the cluster: Number of children in the cluster.

6. Number of females in the cluster: Number of females in the cluster.

7. Age: (1) less than 20 years, (2) 20 to less than 30, (3) 30 to less than 40, (4) 40 to less than 50, (5) 50 to less than 60, and (6) more than 60.

8. Education level: Education level: (1) no education, (2) primary school, (3) middle school, (4) secondary school, and (5) higher education.

9. Past housing experience: Past housing experience: (1) Grid, (2) Shifted-from-grid.

Instrument the questionnaireThe field survey design was used to collect the needed data from subjects in the selected districts of Zaatari Camp. The structured questionnaire consisted of two pages and contained 45 structured and closed-ended questions written in Arabic. The survey included a brief about the study and was divided into three sections: personal information, morphological settlement pattern of the cluster, and efficiency of the settlement. The sections are as follows: (1) Section 1—personal information: This section was designed to collect personal information about the subjects that might influence the relationships in the study. (2) Section 2—settlement patterns: This section was designed to collect data about the settlement patterns of the cluster. (3) Section 3—efficiency of the settlement: This section was designed to collect data about the efficiency of the settlement regarding accessibility, infrastructure, safety, and communication.

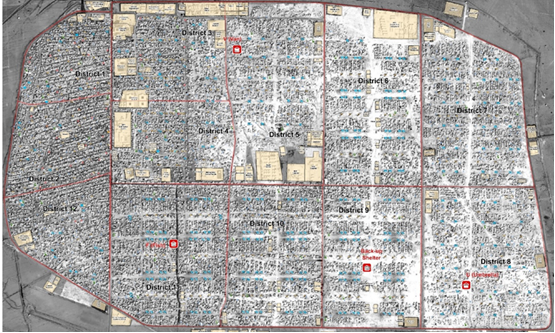

Study areaWith the escalation of the Syrian crisis in 2011, many Syrians fled their homes and sought refuge in Jordan. In a quick response to the massive influx of Syrian refugees into Jordan, the Jordanian government decided on July 28, 2012, to accelerate the construction of the Zaatari camp (see Figure 1). The camp is located near Al-Mafraq city in northern Jordan, about 12 km away from the Syrian border (ACTED, 2014; UNHCR, 2014; UNHCR, 2015). Zaatari camp emerged on a desert tract in the Al-Mafraq Governorate in north Jordan, with a total area of 5.02 km2. In 2015, 86,040 refugees were reported to have settled at the camp. UNHCR, along with a group of NGOs, is mainly in charge of the camp’s management and planning. Refugees have free access to medical services and are provided with infrastructure, food, and education. The old camp area consisted of Districts 1, 2, 3, 4, and 12, which received the first waves of refugees. The situation was chaotic as refugees shifted themselves from the provided grid pattern as a reflection of their higher sense of safety and security. Over time, refugees were spatially controlled into the formally planned grid, mainly in Districts 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, and 11. Of the 12 districts of the camp, six districts (5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10) are covered in this study.

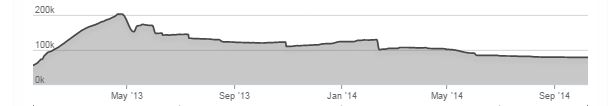

The population of the study consisted of refugees at Zaatari Camp, Mafraq, Jordan. According to statistics in 2015, 86,040 refugees resided in the camp. The population at Zaatari Camp included 24,493 families and 17,494 households. The average household size is 6.58, and in each household, there is an average of 1.38 families (UNHCR, 2014). About 90%–92% of the camp’s population originates from Dara’a in Huran, South Syria. The female population at the camp comprises 50.5% of the total population. In general, 40.3% of the Syrian refugees are aged 18 to 59 years. The number of refugees is increasing in most of the Jordanian governorates, which explains the population decline at the Zaatari Camp. Statistics show that only 20% of the total refugees in Jordan are staying at the camp. In the Mafraq Governorate, refugees reached 76,685, in the Zarqa Governorate 52,074, and in the Irbid Governorate (also near Huran), there are 144,070 refugees (ACTED 2014; UNHCR, 2014). Figure 2 shows the demographic decline in Zaatari camp.

Source: UNHCR, 2014.

Sampling Frame: The sampling frame is taken from maps and statistics of UNHCR, 2015. Zaatari Camp is divided into 12 districts with about 86,040 Syrian refugees in February 2015. Considering the population size in the accessible districts, the studied districts were chosen based on the most common planned population size, which was 8000 refugees; therefore, District 11 was excluded. Accordingly, Districts 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10 were included in the sampling frame. Concerning their characteristics, all districts had a similar population capacity, with an average area of 0.5 km2. District 8 is the only overpopulated district and has the greatest density, whereas the population in District 6 is almost similar to what had been planned for them. However, District 9 has the least population; hence, it is the least dense district.

Sampling Technique: A stratified cluster sampling technique was used as follows. The total number of refugees in the assigned six districts until February 2015 was 44,272, with about 117 clusters. A stratified sampling technique was used to select the sample. Four subjects were assigned to be selected from each cluster in each of the six districts. Therefore, the total sample size was 468 subjects. Stratification was executed for the representation of each cluster in the assigned districts. The unit of analysis was the head of the household.

Sampling Procedure: Subjects were selected randomly from each of the 117 clusters. The selection system started from Al-Yasmeen Street. A subject was selected from the first unit of the first cluster of each district and in every 15th shelter unit. In cases where the selected subject was unavailable or refused to be interviewed, they were excluded and substituted by a subject from the next shelter unit. Clusters in each district were surveyed in a clockwise sequence, and the same subject selection procedure was followed consistently. Districts 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10 were surveyed in sequence. Random selection continued until a sample size of 468 was achieved.

Data Collection Procedures: The survey was conducted as a face-to-face interview using the structured questionnaire in front of the head of the selected household caravan. Visiting time was from Sunday to Thursday, starting at 9 am and ending at 3 pm. The average length of the face-to-face interview was 4 to 7 minutes, and the questionnaire was completed by the researcher. The survey started from District 5 in sequence to the other five districts.

1. Gender: Refugees who participated in the survey were mainly males, comprising 63.9% of the respondents, as shown in Table 1.

2. Place of origin: Of the study respondents, the clear majority originated from Dara’a (South Syria) and comprised 73.7% of the respondents, whereas 17.5% originated from Hums (Central Syria), and 8.8% from other Syrian cities, as shown in Table 1.

3. Length of Stay: Of the respondents, 92.3% were at the camp for more than a year, whereas only 0.6% had a stay of less than one month, as shown in Table 1.

4. Number of Households in the Cluster: The number of households in the cluster ranged between one and seven: 67.9% of the sample had one household in the cluster, 20.1% had two households, and about 0.2% had seven households, as shown in Table 1.

5. Number of Children: The number of children ranged between zero and 12—9.2% of the sample did not have children, 21% had three, and 17.3% had four, as shown in Table 1.

6. Number of Females per Household: Of the respondents, 0.9% did not have females in their families, 29.5% had one, 28.6% had two, and 0.2% had eight, as shown in Table 1.

7. Age: Respondents under 20 years comprised 4.3% of the sample. The most common age, with 37.8% of the sample, was between 30 and 40. Additionally, 4.3% were below 20, and 1.9% were above 60, as shown in Table 1.

8. Education Level: Most respondents were educated. Only 7.9% of the sample lacked literacy, with 31.4% having attended primary school, 25% middle school, 25.9% secondary school, and 9.8% having higher education, as shown in Table 1.

9. Past Housing Experience: Back in their home country, most respondents lived in shifted clusters, whereas only 29.5% of them lived within a planned grid pattern, as shown in Table 1.

| Variable | Percentile | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 63.9 |

| Male | 36.1 | |

| Place of origin | Dara’a | 73.7 |

| Hums | 17.5 | |

| Other | 8.8 | |

| Length of Stay | Less than one month | 0.6 |

| One month-less than six months | 2.8 | |

| Six months-less than 1 year | 4.3 | |

| More than one year | 92.3 | |

| Number of Households | (1) | 68.0 |

| (2) | 20.1 | |

| (3) | 5.7 | |

| (4) | 3.2 | |

| (5) | 2.8 | |

| (7) | 0.2 | |

| Number of Children | (0) | 9.2 |

| (1) | 8.0 | |

| (2) | 16.2 | |

| (3) | 21.0 | |

| (4) | 17.3 | |

| (5) | 16.7 | |

| (6) | 6.6 | |

| (7) | 2.0 | |

| (8) | 1.3 | |

| (9) | 1.3 | |

| (10) | 0.2 | |

| (12) | 0.2 | |

| Number of Females in a Household | (0) | 0.9 |

| (1) | 29.5 | |

| (2) | 28.6 | |

| (3) | 19.0 | |

| (4) | 10.5 | |

| (5) | 8.3 | |

| (6) | 2.1 | |

| (7) | 0.9 | |

| (8) | 0.2 | |

| Age | Less than 20 years | 4.3 |

| 20 years – less than 30 | 19.7 | |

| 30 years – less than 40 | 37.8 | |

| 40 years – less than 50 | 27.6 | |

| 50 years – less than 60 | 8.8 | |

| More than 60 years | 1.9 | |

| Education Level | No education | 7.9 |

| Primary School | 31.4 | |

| Middle School | 25.0 | |

| Secondary School | 25.9 | |

| Higher Education | 9.8 | |

| Past Housing Experience | Linear Pattern | 29.5 |

| Shifted Pattern | 70.5 | |

Linear logistic regression and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests were utilized to test the stated hypothesis in SPSS: The efficiency of the settlement defined in terms of a physical attribute that includes accessibility and infrastructure, and a sociocultural attribute that includes safety and communication, is affected by settlement patterns at Za’atari Camp.

| Sum of Squares | Df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression | 6.51 | 1 | 6.51 | 28.66 | 0.00 |

| Residual | 105.86 | 466 | 0.23 | ||

| Total | 112.376 | 467 |

The total efficiency of the settlement is significantly affected by settlement patterns [F (1, 466) = 28.66, P = 0.00]. The significance of the model suggests that all factors together are affected by settlement patterns being grid or shifted-from-grid. The factors that all together interact include accessibility, infrastructure, safety, and communication. The descriptive analysis suggested that shifted patterns are two-thirds of the sample, indicating that there is an impact of the shifted-from-grid pattern on the efficiency. This relationship can generate either positive or negative impacts. Based on visual analysis and field work in Zaatari, it can be deduced that it is associated with the camp’s social clan structure. That being the case, this relationship has positive impacts on those already supported by their clan in other words communities, and negative impacts on minorities, in other words individuals, since it increases their marginalization. The following ANOVA tests indicate the strength of each factor into the model.

b. An ANOVA test was carried out to measure the effect of settlement patterns on each sub-variable: accessibility, infrastructure, safety, and communication. Results are displayed in Table 3, where significant effects are reported in a decreasing order of strength, as follows.

The strongest significant effect of settlement patterns is on communication in the settlement [F (1, 466) = 31.65, P = 0.00], and mean score (M=3.2). This indicates that the current layout affects the efficiency of communication negatively. Table 3 shows that people were mostly disagreeing with efficiency patterns of communication and most of the sample was living in shifted-from-grid pattern indicating that these shifts affect communication negatively.

Accessibility in the settlement is significantly affected by settlement patterns as well, [F (1, 466) = 29.32, P = 0.00], with a mean score (M=2.5), as suggested by Coresellis et al. (2005) and Bonnin (2012). Table 3 indicates that the shifted pattern leans toward having negative facilitated accessibility, mostly to recreation and schools.

However, infrastructure is not affected by settlement patterns despite suggestions in the literature (Anderson, 1994; Bonnin 2012; Corsellis and Vitale, 2005; Linn, 1983). Safety is also unaffected by settlement patterns because refugees’ sense of safety is highly associated with the social-clan structure of the camp, as indicated by mobilizers (Al-Homoud and Samarah, 2022). Moreover, safety in general is facilitated by being patrolled as a formal settlement.

| Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | Mean | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Accessibility | 2.5 | |||||

| Between Groups | 32.20 | 1 | 32.20 | 29.32 | 0.00 | |

| Within Groups | 511.69 | 466 | 1.10 | |||

| Total | 543.88 | 467 | ||||

| 2. Infrastructure | 3.0 | |||||

| Between Groups | 1.01 | 1 | 1.01 | 1.31 | 0.25 | |

| Within Groups | 358.02 | 466 | 0.77 | |||

| Total | 359.03 | 467 | ||||

| 3. Safety | 2.7 | |||||

| Between Groups | 0.57 | 1 | 0.57 | 1.15 | 0.28 | |

| Within Groups | 231.36 | 466 | 0.50 | |||

| Total | 231.93 | 467 | ||||

| 4. Communication | 3.2 | |||||

| Between Groups | 22.55 | 1 | 22.55 | 31.65 | 0.00 | |

| Within Groups | 332.00 | 466 | 0.72 | |||

| Total | 354.51 | 467 | ||||

A linear logistic regression and one-way ANOVA tests were carried out to assess the sub-hypothesis: The efficiency of accessibility to services in the settlement including schools, education facilities for women, recreation, medical centers, kitchens, and latrines are affected by settlement patterns at Zaatari Camp.

a. Results of linear logistic regression test indicate a significant regression model, [F (1, 466) = 29.32, P = 0.00], Table 4. This suggests that attributes of accessibility all together seem to be affected by settlement patterns, being linear or shifted-from-grid. Consequently, accessibility in the camp is affected by settlement patterns as suggested by the literature (Corsellis et al. 2005; Bonnin, 2012).

| Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression | 32.19 | 1 | 32.19 | 29.32 | .000 |

| Residual | 511.69 | 466 | 1.10 | ||

| Total | 543.88 | 467 |

b. To test the effect on each component of the accessibility attribute, an ANOVA test was carried out. Results are displayed in Table 5, where significant effects are reported in a decreasing order of strength, as follows.

1. Education facilities for Women: Accessibility of education facilities for women in the settlement is significantly affected by settlement pattern, [F (1, 466) = 32.50, P = 0.00].

2. Recreation: Accessibility of recreation spaces is significantly affected by settlement patterns [F (1, 466) = 20.27] , P = 0.00].

3. Schools: Accessibility of schools in the settlement is significantly affected by the settlement pattern, [F (1, 466) = 17.44, P = 0.00].

4. Kitchens: Accessibility of kitchens is affected by settlement pattern, [F (1, 466) = 11.06, P = 0.00].

5. Latrines: Accessibility of latrines is significantly affected by settlement pattern, [F (1, 466) = 4.43, P = 0.04].

6. Medical services: Accessibility of medical services is affected by settlement patterns, [F (1, 466) = 4.17, P = 0.04].

The most affected component of accessibility to settlement patterns is education facilities for women, with a negative direction that is indicated in Table 5. Accordingly, refugees mostly feel that educational facilities for women are not accessible and they mostly live in shifted-from-grid pattern, therefore, it is logical. Refugees’ territorial behavior is shifting the planned grid pattern by creating zones of influence, which affects the accessibility of services (Al-Homoud and Samarah, 2022). This finding is confirmed by the visual data and analysis of mobilizers’ interviews. The least affected components are accessibility to latrines and medical services. These seem to be services most easily replaced at each unit, as latrines are built near shelters without infrastructure and medicines are offered by donors.

| Components | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schools | |||||

| Between Groups | 48.90 | 1 | 48.86 | 17.44 | 0.00 |

| Within Groups | 1305.44 | 466 | 2.80 | ||

| Total | 1354.30 | 467 | |||

| Education Facilities for Women | |||||

| Between Groups | 90.32 | 1 | 90.32 | 32.50 | 0.00 |

| Within Groups | 1295.23 | 466 | 2.78 | ||

| Total | 1385.56 | 467 | |||

| Recreation | |||||

| Between Groups | 43.10 | 1 | 43.10 | 20.27 | 0.00 |

| Within Groups | 990.00 | 466 | 2.12 | ||

| Total | 1033.00 | 467 | |||

| Medical Services | |||||

| Between Groups | 7.10 | 1 | 7.10 | 4.17 | 0.04 |

| Within Groups | 792.11 | 466 | 1.70 | ||

| Total | 799.20 | 467 | |||

| Kitchens | |||||

| Between Groups | 27.51 | 1 | 27.51 | 11.06 | 0.00 |

| Within Groups | 1159.13 | 466 | 2.49 | ||

| Total | 1186.64 | 467 | |||

| Latrines | |||||

| Between Groups | 11.18 | 1 | 11.18 | 4.43 | 0.04 |

| Within Groups | 1175.65 | 466 | 2.52 | ||

| Total | 1186.83 | 467 | |||

A linear logistic regression and one-way ANOVA tests were carried out to assess the sub-hypothesis: The efficiency of infrastructure including indoor and outdoor lighting, walking paths, sewage, garbage disposal, and cleaning maintenance, is affected by settlement patterns at Zaatari Camp.

a. Results of linear logistic regression test indicate an insignificant regression model, [F (1, 466) = 1.31, P = 0.25], as shown in Table 6, contrary to what Linn (1983), Anderson (1994), Corsellis and Vitale (2005), and Bonnin (2012), suggested. However, the following section tests the effect of each component individually.

| Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression | 1.01 | 1 | 1.01 | 1.31 | 0.25 |

| Residual | 358.02 | 466 | 0.77 | ||

| Total | 359.03 | 467 |

b. To test the effect on each component of infrastructure attribute, an ANOVA test was carried out. Results are displayed in Table 7, where significant effects are reported in a decreasing order of strength, as follows.

1. Waste Disposal is affected by settlement patterns [F (1, 466) = 7.47, P = 0.00].

2. Walking Paths is affected by settlement patterns [F (1, 466) = 4.13, P = 0.01].

Garbage disposal depends on NGOs reaching the places for collecting garbage. As some streets are blocked by refugees’ spatial shifts, garbage disposal gets interrupted. It is well understood that walking paths are affected by settlement patterns because streets are subjected to interventions by refugees who extend their private spaces in the clustered pattern and create zones of influence (Al-Homoud and Samarah, 2022). Most of the sample indicated negative efficiency of the provided walking paths, probably for the above reason. However, indoor lighting, outdoor lighting, sewage, and cleaning maintenance are unaffected by settlement patterns. These variables appear to be inefficient regardless of the pattern.

Furthermore, components provided to the camp that cannot be controlled by refugees are unaffected by the settlement patterns, such as indoor and outdoor lighting, which is provided by the Jordanian government. Regarding sewage, refugees’ private latrines and kitchens are not connected at all to the infrastructure network of the camp. Cleaning maintenance might be an individual issue that depends on the hygiene standards of the family.

| Components Indoor lighting | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Between Groups | 0.05 | 1 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.88 |

| Within Groups | 883.48 | 466 | 1.90 | ||

| Total | 883.53 | 467 | |||

| Outdoor Lighting | |||||

| Between Groups | 0.19 | 1 | 0.19 | 0.11 | 0.73 |

| Within Groups | 772.45 | 466 | 1.66 | ||

| Total | 772.64 | 467 | |||

| Walking Paths | |||||

| Between Groups | 5.99 | 1 | 5.99 | 4.13 | 0.04 |

| Within Groups | 675.42 | 466 | 1.45 | ||

| Total | 681.41 | 467 | |||

| Sewage | |||||

| Between Groups | 0.32 | 1 | 0.32 | 0.20 | 0.65 |

| Within Groups | 752.88 | 466 | 1.62 | ||

| Total | 753.20 | 467 | |||

| Garbage Disposal | |||||

| Between Groups | 11.03 | 1 | 11.03 | 7.47 | 0.01 |

| Within Groups | 687.71 | 466 | 1.48 | ||

| Total | 698.74 | 467 | |||

| Cleaning Maintenance | |||||

| Between Groups | 1.21 | 1 | 1.21 | 1.05 | 0.31 |

| Within Groups | 537.74 | 466 | 1.15 | ||

| Total | 538.95 | 467 | |||

A linear logistic regression and one-way ANOVA tests were carried out to assess the sub-hypothesis: The sense of safety within the settlement including protection of self and family, protection of self and family with the help of neighbors, protection of self and family with the help of relatives, protection of belongings, protection of belongings with the help of neighbors, and protection of belongings with the help of relative, is affected by settlement patterns at Zaatari Camp.

a. Results of linear logistic regression test indicate an insignificant regression model [F (1, 466) = 1.15, P = 0.28], as shown in Table 8. This indicates that safety components all together are not affected by settlement patterns. Although mobilizers perceive that settlement patterns affect sense of safety of the community, which is supported by literature (UNHCR, 2002; Corsellis and Vitale, 2005), this does not apply to our case of inquiry. Statistically, safety in Zaatari camp is not affected by settlement patterns all at once. However, a one-way ANOVA was carried out to test the effect on each component individually.

| Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression | 0.57 | 1 | 0.57 | 1.15 | 0.28 |

| Residual | 231.36 | 466 | 0.50 | ||

| Total | 231.93 | 467 |

b. To test the effect on each component of safety attribute, an ANOVA test was carried out. Results are displayed in Table 9.

| Components | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protection of Self and Family | ||||||||

| Between Groups | 0.03 | 1 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.84 | |||

| Within Groups | 399.58 | 466 | 0.86 | |||||

| Total | 399.61 | 467 | ||||||

| Protection of Self and Family- neighbors | ||||||||

| Between Groups | 0.03 | 1 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.89 | |||

| Within Groups | 619.45 | 466 | 1.33 | |||||

| Total | 619.48 | 467 | ||||||

| Protection of Self and Family-relatives | ||||||||

| Between Groups | 2.93 | 1 | 2.93 | 2.07 | 0.15 | |||

| Within Groups | 660.68 | 466 | 1.429 | |||||

| Total | 663.61 | 467 | ||||||

| Protection of Belongings | ||||||||

| Between Groups | 0.37 | 1 | 0.37 | 0.34 | 0.56 | |||

| Within Groups | 506.58 | 466 | 1.09 | |||||

| Total | 506.95 | 467 | ||||||

| Protection of Belongings-neighbours | ||||||||

| Between Groups | 2.14 | 1 | 2.14 | 1.57 | 0.21 | |||

| Within Groups | 633.83 | 466 | 1.36 | |||||

| Total | 635.97 | 467 | ||||||

| Protection of Belongings-relatives | ||||||||

| Between Groups | 1.80 | 1 | 1.80 | 1.11 | 0.29 | |||

| Within Groups | 752.26 | 466 | 1.61 | |||||

| Total | 754.06 | 467 | ||||||

As shown in the Table 9, none of the safety components is affected by settlement patterns due to the homogeneous nature of the sample. Results indicate that refugees do not seem to be able to protect themselves or their belongings, and they do not seek protection from neighbors or relatives. Moreover, refugees do not feel safe despite the clan identity of the camp that is expected to give clan and family members a sense of safety.

Effect of settlement patterns on communicationLinear logistic regression and one-way ANOVA tests were carried out to assess the sub-hypothesis: efficiency of communication including getting information, getting information updates, getting information from a place, getting information from a contact, raising concerns in a place, raising concerns to a contact, and raising concerns to mobilizers is affected by settlement patterns at the Zaatari Camp.

a. Results of the linear logistic regression test indicate a significant regression model, [F (1, 466) = 31.65, P =0.00], as shown in Table 10. All components of communication are affected by settlement patterns simultaneously, as suggested by mobilizers and mentioned in the literature by Linn (1983), Anderson (1994), Corsellis and Vitale (2005), and Bonnin (2012). However, the strength of the effect on each component is attested in the following section.

| Sum of Squares | Df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression | 22.55 | 1 | 22.55 | 31.65 | 0.00 |

| Residual | 331.96 | 466 | 0.71 | ||

| Total | 354.51 | 467 |

b. To test the effect on each component (assigned questions), a one-way ANOVA test was carried out. Results are displayed in Table 11, where significant effects are reported in a decreasing order of strength, as follows.

1. Getting Information—Place: is affected by settlement patterns, [F (1, 466) = 55.36, P = 0.00]. This effect is negative, they mostly do not know where to go in place.

2. Raising Concerns—Place: is affected by settlement patterns, [F (1, 466) = 45.18, P = 0.00].

3. Getting Information—Contact: is affected by settlement patterns, [F (1, 466) = 34.20, P = 0.00].

4. Raising Concerns—Mobilizers: is not affected by settlement patterns, [F (1, 466) = 0.72, P = 0.40].

5. Getting Information—Updates: is affected by settlement patterns, [F (1, 466) = 21.47, P = 0.00].

Results indicate that refugees are mostly place-dependent in obtaining their information, and they are localized. Second, refugees depend on social contacts. Analysis indicated that refugees do not know where to go in places nor whom they should contact. Moreover, settlement patterns do not seem to statistically affect raising concerns to mobilizers and obtaining information. In general, this could be because the used means of communication are not dependent on spatial issues, such as word of mouth, as indicated by mobilizers.

| Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Getting Information | |||||

| Between Groups | 2.5 | 1 | 2.52 | 2.02 | 0.15 |

| Within Groups | 577.82 | 466 | 1.24 | ||

| Total | 580.33 | 467 | |||

| Getting Information-updates | |||||

| Between Groups | 23.10 | 1 | 23.10 | 21.47 | 0.00 |

| Within Groups | 501.44 | 466 | 1.08 | ||

| Total | 524.54 | 467 | |||

| Getting Information-place | |||||

| Between Groups | 54.48 | 1 | 54.48 | 55.36 | 0.00 |

| Within Groups | 458.60 | 466 | 0.98 | ||

| Total | 513.08 | 467 | |||

| Getting Information-contact | |||||

| Between Groups | 36.81 | 1 | 36.81 | 34.20 | 0.00 |

| Within Groups | 501.57 | 466 | 1.08 | ||

| Total | 538.38 | 467 | |||

| Raising Concern-place | |||||

| Between Groups | 46.16 | 1 | 46.16 | 45.18 | 0.00 |

| Within Groups | 476.16 | 466 | 1.02 | ||

| Total | 522.33 | 467 | |||

| Raising Concern-contact | |||||

| Between Groups | 29.34 | 1 | 29.34 | 24.99 | 0.00 |

| Within Groups | 547.04 | 466 | 1.17 | ||

| Total | 576.38 | 467 | |||

| Raising Concern-mobilizers | |||||

| Between Groups | 1.16 | 1 | 1.16 | 0.72 | 0.40 |

| Within Groups | 749.83 | 466 | 1.61 | ||

| Total | 751.00 | 467 | |||

Findings indicate that the spatial shifts influence mobilizers’ reachability in terms of accessibility, infrastructure, safety, and communication. Statistical tests of significance were used to test the hypotheses of the study, with results confirming the research hypotheses. Accordingly, the efficiency of the settlement is affected by settlement patterns. Strong and weak types of relationships were found among the study variables, including settlement patterns, the efficiency of the settlement, and driving engines behind settlement patterns.

Strong Relationships: (1) Accessibility: Results attested that settlement patterns affect accessibility and all of its components, including schools, educational facilities for women, recreation, medical services, kitchens, and latrines. (2) Infrastructure: Of the infrastructure components, walking paths and garbage disposal are affected by settlement patterns. (3) Communication: Settlement patterns affect communication. Five of its components include obtaining information updates, retrieving information from a place, getting information from a contact, raising concerns at a place, and raising issues to a contact. Weak Relationships: (1) Infrastructure: Infrastructure and four of its components are unaffected by settlement patterns: indoor lighting, outdoor lighting, sewage, and cleaning maintenance. (2) Safety: Neither safety nor any of its six components are affected by settlement patterns. The components include the protection of self and family, protection of self and family with the help of neighbors, protection of self and family with the help of relatives, protection of belongings, protection of belongings with the help of neighbors, and protection of belongings with the help of relatives. (3) Communication: Of the communication components, obtaining information is not affected by settlement patterns.

Recommendations for Stakeholders: As refugee camp planners’ central concern is to achieve the maximum efficiency of settlement, they should consider spatial patterns that cannot be manipulated by refugees. Implementing this pattern will avoid strengthening one group at the expense of the other. The following deduced recommendations are directed to particular stakeholders: (1) Planners: It is recommended to consider refugees’ sociocultural needs in the planning process and potentially refugees as urban actors. According to the exploration, waves of refugees arrive gradually over time; thus, the camp should be expanded in phases instead of a one-time planning process. (2) Refugee camp officials and donors: The emerging clustered spaces that were created by refugees can be adapted to generate future spatial patterns. The emerging spatial shifts should then be enhanced by integrating the social structure with the spatial system of the settlement with more sensitivity. This is considered as an attempt to achieve the open-ended planning of such settlements with participatory and cooperative approach with refugees. Future studies will explore spatial self-organization as a steppingstone for an alternative planning approach in Syrian refugee camps in Jordan.

Implications and Learning lessons: Refugee camps are like slums in their relation to the city; they turn into urbanized space. What is common among such settlements is how spaces emerge and connect to social, economic and physical context; and how they evolve over time. Such issues call upon architects, planners and development experts to engage with the attributes of informal settlements in different cities around the world in a more constructive and sensitive engagement. To what constitutes such settlements rather than being an urban space associated with infrastructure. To make such space for inhabitants to live in with dignity.

Conceptualization, M. A.-H. and O. S.; methodology, M. A.-H. and O. S.; investigation, M. A.-H. and O. S.; resources, M. A.-H. and O. S.; data curation, M. A.-H. and O. S.; writing—original draft preparation, M. A.-H.; writing—review and editing, M. A.-H.; supervision, M. A.-H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of the paper.

We thank officials at Zaatari Camp for their supporting the field work.