2023 Volume 11 Issue 4 Pages 93-112

2023 Volume 11 Issue 4 Pages 93-112

The 11th agenda of SDGs has become an utterly important mission of governments worldwide to create and sustain livable urban settlements. Rapid urbanization becomes one of the reason for the urgency. This research aims at understanding the spatial transformation of the largest resettlement project from the river bank area in secondary city of Surakarta, Indonesia. This research applies a case study method with quantitative and qualitative data from questionnaires and interviews. The data collection process is conducted through three stages, the interview to the government officials to understand the resettlement policy, followed by questionnaire to the resettled household, and the last stage is interview to the head of community of the resettlement area. The survey data is analyzed with the Wilcoxon signed-rank test and the interview with content analysis. The results demonstrate that a collaborative process plays a crucial role in the success of the resettlement project. Within nine years after the resettlement, the site has significantly transformed from a rural area lacking infrastructure and services to an urbanized area with a rapid intensity of economic activities. The collaborative process has eased the settlers’ adaptation since the beginning of resettlement and has led to improved livelihood assets such as land tenure, housing, and urban infrastructure as well as social assets. This also initiates opportunities for future development of the area.

Rapid urbanization and the lack of affordable housing have led to the emergence of slums in many cities, particularly in developing countries (Ooi and Phua, 2007). Resettlement programs are one way to address the issue of slums and improve the living conditions of the affected communities (Viratkapan and Perera, 2006). Resettlement involves moving people from their current location to a new one, where they can access better living conditions and basic services (World Bank, n.d, as cited in Walelign and Lujala, 2022). Resettlement can also be a response to environmental disasters or other forms of displacement, such as conflict or development projects (Terminski, 2013).

In many rapidly urbanizing cities, slum dwellers occupy illegal land, which poses a challenge to the resettlement process. Resettlement programs require legal land ownership to be viable and sustainable in the long term, which means that governments must be able to provide land security for the resettled community (Zhou, Peng, et al., 2017). Furthermore, the resettlement process should be based on government plans and social consultation with the affected community. This means that the affected community should be involved in the decision-making process and should have a say in where they are resettled and adequate support mechanisms in the new place of residence are also essential for the resettlement program to be successful (Terminski, 2013).

Resettlement programs can have significant impacts on the affected communities. These impacts can include changes in income levels, cultural and social values, norms, and bonds (Syagga and Olima, 1996). Resettlement programs can be a solution to various problems such as post-political conflict areas, poverty, and the effects of climate change. (Kinsey, 2004). Resettlement programs can also be undertaken to cope with the problems of climate change where settlers came from a drought-prone poor county (Rogers and Xue, 2015), and flood-prone areas (Artur and Hilhorst, 2014). These resettlement programs aimed to reduce vulnerability in living areas and improve the living conditions of the affected communities.

On the other hand, resettlement programs can also pose risks to the resettled community. These risks can include increased hazards during the construction stage, social disarticulation, economic deprivation, and loss of access to common property. The resettled community may also experience a lack of urban services and infrastructure, low accessibility, joblessness, and food insecurity (Cernea, 2000; Chen, Tan, et al., 2017; Navarra, Niehof, et al., 2013; Terminski, 2013). Furthermore, the resettled community may have difficulty adapting to the new location and establishing new social relations, economic activities, and neighborhood institutions. This can result in further impoverishment of the involuntarily resettled households, and they may have low ability to recover their lives after marginalization caused by resettlement (Navarra, Niehof, et al., 2013).

Furthermore, there are two approaches to resettlement programs: the voluntary and involuntary one. The involuntary or state-led resettlement has been considered divisive, as it is seen as an authoritarian approach (Arandel and Wetterberg, 2013). This approach could be triggered by a compulsory land acquisition for public services (Syagga and Olima, 1996). Very often, the new living environment designated based on this approach is not appropriate to live in (Hardoy & Satterthwaite, 1981, as cited in (Sengupta and Sharma, 2009). Moreover, since its goals are commonly based on economic and social targets set by the government, it does not include the needs of resettled households. Consequently, intangible needs are ignored (Arandel and Wetterberg, 2013). Bardhan, Sarkar, et al. (2015) argue that the leading factor to the failure of state-led resettlement programs is the lack of participation of the resettled households, as the program does not involve the perspectives of the dwellers. Therefore, such resettlement program is dominantly perceived as increasing impoverishment of resettled households (Navarra, Niehof, et al., 2013). However, despite many critics to state-led resettlement, it is regarded as having a positive side because the process is quite straightforward and efficient in terms of time utilization.

Concerning some failures of state-led resettlement, the alternative approach of grassroots-led or voluntary resettlement programs has been proposed (Bardhan, Sarkar, et al., 2015). Such approach to resettlement is perceived to be inclusive and thus allows direct stakeholders to internalize their power. In some specific cases, grassroots-led resettlements are quite successful for some particular reasons, which mostly include accommodating the resettled households’ interests, available funding, and good negotiation processes with the government. The scale of such grassroots-led resettlements is usually quite small, for example, covering merely 44 households out of 142 total households (Sengupta and Sharma, 2009). Moreover, Arandel and Wetterberg (2013) are concerned that in addition to being time-consuming, an empowerment approach to resettlement might ignore power relations among communities and open the potential for elite co-optation.

Regarding the importance of recognizing tangible and intangible needs of the resettled households, discussions around resettlement often emphasize the importance of creating sustainable livelihoods in the new resettlement areas. A sustainable livelihood approach is characterized by being people-centered, responsive, participatory, and considering multiple levels of perspective. It involves partnerships between the public and private sectors to ensure the success of such initiatives (Serrat, 2017). The sustainable livelihood approach serves as an analytical framework to identify the essential assets needed by a community for their daily activities, including various organizations and institutions that play a role in supporting livelihoods. This approach helps in understanding and addressing the specific needs and challenges faced by the resettled population. The framework recognizes five key assets at the neighborhood level (Chimhowu and Hulme, 2006): natural capital, physical capital, human capital, and financial capital.

Assessing the five neighborhood assets is indeed crucial when evaluating the success of a resettlement program from a people-centered perspective. The ability of resettled communities to adapt to their new environment is a key factor in determining the program's success. In some cases, resettled communities are able to expand their networks and continue their economic activities in the new resettlement areas (Artur and Hilhorst, 2014). For such expansion and the creation of new activities to be successful, it is essential to have basic urban services and infrastructure in place. Access to services such as water, sanitation, electricity, transportation, healthcare, education, and communication facilities greatly contributes to the sustainability of new livelihoods (Septanti, Budi, et al., 2023). These services are vital for improving the quality of life for resettlers and enabling them to engage in productive activities. Therefore, integrating the government's working plans into the resettlement program is crucial to achieving success. This integration ensures that the program aligns with broader development objectives and strategies (Duan and Wilmsen, 2012).

The above discussion mentions that involving many stakeholders in resettlement programs is required. For this requirement, the idea of collaborative approach to planning and decision-making may fit the context. It emphasizes the importance of cooperation and participation from various actors, including the government, communities, and private sectors. Collaborative approach in planning and decision-making that involves engaging multiple stakeholders in the process, aiming to create a more democratic and inclusive decision-making process. This approach is influenced by Habermas' theory of communicative rationality, which emphasizes the importance of open and honest communication among participants. The collaborative planning process is designed to foster intense interaction and dialogue among stakeholders, with the goal of building their capacity and creating a shared understanding. Through this process, it is expected that a solid and convergent frame of reference can be developed voluntarily (Healey, 2006).

Implementing the collaborative planning framework can be challenging (Roy, 2015). It requires considerable time, effort, and resources to engage and coordinate with diverse groups. Additionally, conflicting interests, power dynamics, and varying levels of commitment from stakeholders can hinder the success of the collaborative approach in practice. Nevertheless, beyond the criticism it has received, some scholars have proved its effectiveness in practice. Overall, the collaborative approach to planning offers a potential avenue for more inclusive and democratic decision-making, but its practical implementation requires careful consideration of the specific context, stakeholders' characteristics, and effective facilitation to overcome challenges, increased trust, empathy, and maximize its benefits (Haller, 2017; Vogt, Jordan, et al., 2016; Weigand, Flanagan, et al., 2014).

This study aims to examine the effectiveness of a collaborative process in resettlement programs by assessing its impact on livelihood assets in the new resettlement area. Previous research has focused on government-led and community-based approaches separately, leaving a gap in understanding the potential benefits of combining both approaches. The research question addresses the extent to which the collaborative process improves livelihood assets. The study analyzes the process of resettlement, considers pre-resettlement livelihood assets as a baseline, and evaluates how these assets change during and after the resettlement through collaboration. The conceptual framework presented in Figure 1 outlines the stages of the collaborative process in resettlement programs and its potential impact on livelihood assets.

The framework aims to guide the investigation into the extent to which the collaborative process can improve livelihood assets in the new resettlement area. The framework consists of the following analysis: (1) Resettlement process analysis: this stage involves the actual process of resettlement, where the community is relocated to a new area. Focus on the process of collaboration between the government and the community in the decision-making processes. This stage explores the extent to which the community is involved in decision-making, planning, and implementation of the resettlement processes; (2) Pre-resettlement and post resettlement community’s assets assessment: this stage focuses on understanding the baseline or initial livelihood assets of the community and to what extent it has modified as a result of the collaborative process. It examines whether there have been improvements or declines in the various livelihood capitals.

In Indonesian context, considering its culture of mutual assistance, tolerance, and empathy, as well as its current context of decentralization where community and local government become important stakeholders that have been creating dynamic change of governance over the last twenty years, this paper argues that collaborative planning may work for the framework of resettlement planning in Indonesia, particularly for medium-sized cities that retain a strong traditional culture. The methodology section will discuss three points arranged in three sub-sections: locus of study, methods, and analytical tools.

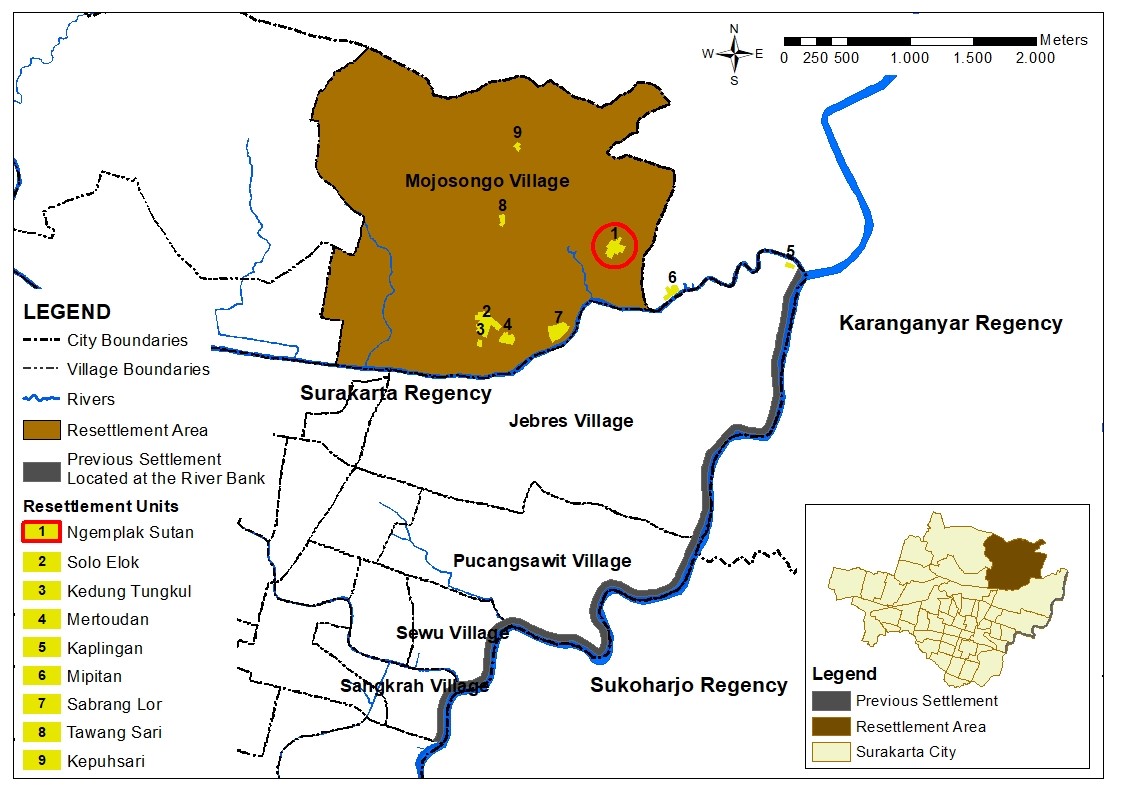

Locus of studyThe research was conducted in Surakarta City, a medium-sized city located in Central Java, Indonesia. Surakarta has a population of 522,364 people as of 2020, according to Surakarta Central Statistics. The city covers an area of 44.04 square kilometres, resulting in a high population density of 11,353 persons per square kilometre. This makes Surakarta the most densely populated city in Central Java Province. Being a rapidly urbanizing city, Surakarta faces various development challenges, including the presence of slum areas. More than half of Surakarta's urban villages, specifically 28 out of 54 kelurahan, are affected by slums. Some of these squatter settlements are located along the riverbanks of Bengawan Solo, as indicated in Figure 2.

From December 26th 2007 to January 1st 2008, the flooding of the Bengawan Solo River in Surakarta, impacted 6,368 households in three sub-districts (kecamatan): Serengan, Pasar Kliwon, and Jebres. 1,571 impacted households are living in squatter settlements along the Bengawan Solo river bank (The Government of Surakarta, 2008). As a response to the disaster and to ensure the safety of the residents, the local government of Surakarta initiated a resettlement program. Under this program, a total of 453households from the squatter settlements were relocated to safer residential areas. These households were resettled in three kelurahan (urban village) within Surakarta City, namely Mojosongo, Jebres, and Sangkrah. Additionally, other kelurahan in the neighboring Boyolali Regency and Sukoharjo Regency also accommodated some of the relocated households.

The research focused on Kelurahan Mojosongo in Surakarta City as the main case study area for the resettlement program. Out of the total 1,571 households affected by the Bengawan Solo flood in 2007, 327 households were relocated to Mojosongo, making it the primary area for resettlement. These households were originally from four prone areas along the Bengawan Solo riverbanks: Pucangsawit, Jebres, Sewu, and Sangkrah. The households that were resettled in Kelurahan Mojosongo were distributed across nine different locations within urban neighborhoods. The research likely examined the impact of the resettlement program in these specific locations, considering component of livelihood assests. Figure 2 and Table 1, which were referenced in the research, provided visual representations and detailed information about the distribution of the resettled households within Kelurahan Mojosongo, helping to illustrate the scale and extent of the resettlement efforts in the area.

| No | Previous village where settlement located at the river bank | Resettlement destination | Total resettled households | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Village/sub-district | Resettlement area | 2010 | 2018 | ||

| 1 | Pucangsawit | Mojosongo/ Jebres/ Surakarta | (1) Ngemplak Sutan | 112 | 112 |

| (2)Solo Elok | 89 | 91 | |||

| (3)Kedung Tungkul | 18 | 21 | |||

| 2 | Jebres | Mojosongo/ Jebres/ Surakarta | (4)Mertoudan | 25 | 38 |

| (5)Kaplingan | 22 | 25 | |||

| (6)Mipitan | 11 | 84 | |||

| (7)Sabrang Lor | 24 | 60 | |||

| 3 | Sewu | Mojosongo/ Jebres/ Surakarta | (8)Tawang Sari | 13 | 25 |

| 4 | Sangkrah | Mojosongo/ Jebres/ Surakarta | (9)Kepuhsari | 13 | 16 |

| 327 | 472 | ||||

Sources: Community Empowerment Agency of Surakarta City (2012) and field works, 2018

The study applied a case study approach as its research method, utilizing both qualitative and quantitative data and analysis techniques. Data collection for the study was conducted in 2019, specifically from June to September, and was carried out in two stages.

The first stage of data collection involved interviews with two types of stakeholders: (1) government institutions to gain an understanding of the resettlement housing policy in Surakarta and its implementation as part of a flood mitigation policy. The purpose of this stage was to gather general insights and local perspectives on how the city addressed the issues of informal settlements along the riverbank areas; (2) the head of the neighborhood unit in Ngemplak Sutan as representative of community. They were chosen because they were considered to have a good understanding of the entire collaborative process and operationalization of the resettlement program, from its early stages to the current situation. This interview stage aimed to delve into the process and mechanisms of the local collaborative planning approach employed in the Surakarta resettlement project. Particularly, the interview with the head of the neighborhood unit aimed to corroborate and validate the data obtained from the questionnaires delivered to community regarding the provision of urban services as components livelihood assets. Table 2 provides information on the interviewees.

| No | Name of Institutions | Number |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Head of Local Development Planning Agency | 1 person |

| 2 | Head of Local Public Works Agency | 1 person |

| 3 | Head of Local Agency for Housing, Settlement Areas and Land Use | 1 peson |

| 4 | Head of a Community Working Group (POKJA) | 1 person |

| 5 | Head of Neighborhood Unit of Ngemplak Sutan Resettlement Area | 1 person |

The second stage was a survey with a questionnaire, which used simple random sampling with a degree of confidence of 95% applied to the population resettled in Ngemplak Sutan negihborhood, Kelurahan Mojosongo that consists of 112 households. From 78 respondents, eight questionnaires are rejected, so the total acceptable sample is 70 households. The Ngemplak Sutan neighborhood was selected as the location for this study because it accommodated the largest number of resettlers, which is 112 out of 327 resettled households in Kelurahan Mojosongo. This survey is intended to examine variables affecting the transformation of the neighborhood assets before and after resettlement project. The variables/ components used in this research were shown in Table 3.

| No | Component of analysis | Sub component | Techniques of data gathering | Sources of data |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | The Process | Process of operation of Resettlement since pra- resettlement phase to resettlement phase | Interview |

- Head of POKJA - Surakarta Government Units |

| 2 | The transformation of Neighborhood Resettled Units |

Livelihood Assets Provision before and after resettlement related to Land tenure Condition of Houses Clean Water Services Loan Ownership Comfortability Condition of Sanitation Condition of Road Occupation Ability of adaptation Skill Income Stability Education Facility |

Questionnaire survey | 70 respondents of Ngempka Sutan Resettlement unit |

| The transformation of area resulted from provision of infrastructure and services from the Government | Interview | Head of Neiborhood Unit of Ngemplak Sutan Resettlement Unit |

The data collected from the questionnaire survey examining the transformation of livelihood assets of the neighborhood because of the resettlement project from 2010 to 2019. The data of livelihood assets was therefore analyzed using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. This test is a nonparametric test for one-sample location problems, usually applied to compare two dependent samples (Rey and Neuhäuser, 2011). The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was conducted with the IBM SPSS 25 software. If the p-value (Asymp. Sig. (2-tailed)) resulting from this test is less than the critical research limit (α=0.05), it can be inferred that there is a significant difference between before and after resettlement.

The analysis of the interview results was conducted based on several main categories of information. These categories included:

By analyzing the interview results within these categories, the study could gain valuable insights into the outcomes and effectiveness of the resettlement program in Ngemplak Sutan, particularly in terms of livelihood assets through collaborative processes.

This section is divided into 2 parts. Fist part describes the results from the interview survey from key persons listed in Table 2 about the resettlement process, and the second part explained the transformation process of livelihood assets affected by the provision of urban services and infrastructure in the resettlement area.

Collaborative Resettlement ProcessThe content analysis of the interview survey highlights key aspects of the resettlement process, emphasizing the collaborative nature of decision-making and resource allocation. The first step is the formation of the POKJA in each village, which represent the resettled households. The POKJA was selected through “rembug warga” (discussion of stakeholders in the village level) and legalized by the Mayor’s Decree. This process signifies a participatory approach in the implementation of the program. One of the important roles of the POKJA is to conduct the data identification process, ensuring that eligible households are identified for the resettlement program.

This step ensures that the community members themselves have a say in the selection process, enhancing the inclusivity and transparency of the program. The identification results are submitted as a proposal for resettlement program to the city government. This demonstrates the involvement of the government in overseeing the program and providing resources for its implementation. The government's approval of the proposal indicates their recognition of the community's perspective and the importance of their involvement in the decision-making process.

The distribution of grants is conducted in two stages. The first stage grant enables households to purchase land (IDR 12 million per household), while the second stage grant supports the construction of new housing (IDR 8.5 million per household). The significant total investment of IDR 3.92 billion to 327 households indicates a commitment to supporting the community's transition to the new resettlement area.

Table 4 shows the collaboration of 5 institutions led by the mayor of Surakarta. Support from different institutions can be effectively operated with the collaborative resettlement process. The Local government’s Agency of Community Empowerment, Woman Empowerment, Child Protection and Family Planning provided a subsidy of IDR 8.5 million for housing construction for each household. The Coordinating Ministry of Social Welfare, provided a subsidy of IDR 12 million for each household for land purchase in the resettlement destination area. Later on, Water Utilities (PDAM) and State-owned Enterprise for Electricity (PLN) have distributed clean water supply and electricity to the households based on the proposal.

All 327 households from 4 villages were requested to engage in discussions with their each POKJA to determine their preferred location for relocation. Through this collaborative approach, an agreement was reached on Mojosongo Urban Village as the chosen resettlement location. Since there was no available vast vacant land to accommodate all households in a single location, nine different locations within Mojosongo were identified as location for the resettlement, called as neighborhood units.

The selection of these locations was primarily based on affordability and land availability, considering the funding constraints. The collaborative process of land selection aimed to mitigate the potential social shock experienced by the settlers due to displacement and facilitate their adaptation to the new livelihoods in the resettlement area. By involving the community in the decision-making process, the POKJA aimed to mobilize and engage them, ensuring their perspectives were taken into account. This approach also aimed to minimize conflicts at the grassroots level, drawing from the insights of Sengupta and Sharma (2009) in the case of Kathmandu.

Overall, the involvement of the POKJA and the collaborative decision-making process helped bring the resettled households into the center of the decision-making process and reduce potential conflicts. This participatory approach acknowledges the importance of community perspectives and aims to enhance the overall success and acceptance of the resettlement project.

| No | Government institutions supporting the resettlement | Role of the government | The collaborative resettlement process | The Outcome of the Resettlement project |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Coordinating Ministry of Social Welfare | The Coordinating Ministry of Social Welfare provided a subsidy of IDR 12 million for each household for land purchase in the resettlement destination area. | The designated land was selected by the households themselves coordinated by the Head of POKJA. | As in the previous settlement, the households lived in informal land status with no security of tenure in the riverbank area, in the resettlement area, all the households of settlers obtained residential land, which has the security of tenure. |

| 2 | Mayor of Surakarta | The Mayor of Surakarta established the Mayor Regulation no. 15/2017, which implies the formulation of POKJA for the resettlement. | POKJA had the responsibility to identify households eligible to receive subsidy from the resettlement program. | The working group (POKJA) also coordinated the purchase of land in a collective way, so the resettles living in the same neighborhood in the previous settlement can be located together in the same neighborhood unit in the resettlement area. |

| 3 | Local government’s Agency of Community Empowerment, Woman Empowerment, Child Protection and Family Planning | The government unit provided a subsidy of IDR 8.5 million for housing construction for each household. | The households were granted preference to build and construct their houses according to their affordability. Some households brought used building materials from their previous houses in the river bank area, and employed family members as building laborers to save construction costs and other self-help construction methods. | By constructing houses supported by the Government subsidy of IDR 8,5 million, the resettlers can live in permanent houses fulfilling the standard from theMinistry of Housing and Public Works. |

| 4 | Local Agrarian Bureau | Establishing land tenure security for each household in the destination area of resettlement | The certificate issued can be used by the resettled households as collateral for bank loans for startup capital. | The eligibility of households in obtaining loans is increased because of the ownership of land. . |

| 5 | Water Utilities (PDAM) | Water Utilities provided water networks to the households. | The process of identification of demands and preparation of a proposal to Water Utilities (PDAM) was conducted by POKJA and the community. | Provision of water network is improved |

| 6 | State-owned Enterprise for Electricity (PLN) | Installment of an electric power network in all areas of the resettlement | The process of identifying demands and preparing a proposal to PLN was conducted by POKJA and the community. | Proposal accepted by PLN and the resettlement unit has been evenly distributed by Electricity services |

Following the completion of the location selection process, the land parcels in the chosen locations received land titles from the National Land Agency of Surakarta. Subsequently, the second grant, amounting to IDR 8.5 million for housing construction, was distributed to the beneficiaries. However, the disbursement of this grant was contingent upon the fulfillment of all land tenure and administration procedures, which were ensured by the city government.

The POKJA played a coordinating role in the construction process by implementing a self-help housing construction approach. They engaged in intensive communication and held meetings with the community to facilitate the construction process. Due to limited funds, the resettled households employed various strategies to complete the construction. Some brought construction materials from their previous houses in the squatter settlement areas, while others supplemented the funds with their own savings. Additionally, some households participated in the construction work themselves, reducing the need to hire external construction workers.

Through these strategies, the resettled households actively engaged in the construction process, fostering a sense of familiarity with their new neighborhood. Their involvement allowed them to familiarize themselves with the new surroundings and gradually adapt to their new living environment. Overall, this process emphasizes the community's active involvement in the building process, highlighting their dedication and willingness to contribute to their own resettlement. In order to facilitate a smoother transition and the possibility of long-term adaption in the new neighbourhood, the self-help approach and the use of available resources allow the resettled households feel a feeling of ownership and empowerment.

The cooperative land buying and housing construction process was largely responsible for increasing the household's human and financial capital. The community members actively participated in decision-making and contributed to the construction of their own homes, giving them a sense of ownership and control over their living conditions. The relocated community was able to decrease the shock they had when adjusting to their new environment because of this process, with their own choice of site and ability to enhance their financial by having new dwellings with secured land tenure. By empowering the community and enhancing their capital, the collaborative process contributed to their overall resilience and ability to navigate the challenges of the resettlement.

Once the program was completed, the POKJA prepared an accountability report for the city government. This report outlines the details of the program, including the process followed, the utilization of funds, and the outcomes achieved. The accountability report is an essential aspect of ensuring transparency and assessing the effectiveness of the collaborative process in achieving its intended goals.

The Transformation of Livelihood Assets through Spatial Transformation of the Neighborhood UnitThe data collected through the questionnaire provides insights into the demographic characteristics of the heads of households and their engagement in income-generating activities. It also hints at the assessment of various livelihood assets before and after resettlement. The assets assessed are land tenure, housing conditions, access to clean water services, loan ownership, and comfortability. Data reveal that, the heads of households were dominated by those aged 31 to 50 years at 55.7%, whereas 30% of them were more than 51 years old and only a few were less than 30 years old (14.3%).

The households have income-generating activities in order to fulfil their daily needs. As they were previously squatter settlers, most of their economic activities were income-earning activities in the informal sector (58.6%). They were mostly engaged in such activities as craftspeople, food stallers, construction workers, drivers, parking attendants, etc. Only a few settlers worked as private employees (21.4%) and there were no settlers who worked as government employees.

| No. | Livelihood asset | Before resettlement | After resettlement | Asymp. Sig. (2-tailed) | Results of Analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of households | Percentage to total households | Number of households | Percentage of total households | ||||

| 1 | Land tenure | ||||||

| a. No legal status | 40 | 57.1 | 2 | 2.9 | 0.000 | Significantly different | |

| b. In the process of legal status | 2 | 2.96 | 0 | 0.0 | |||

| c. Has land tenure security | 28 | 40.0 | 68 | 97.1 | |||

| Total | 70 | 100.0 | 70 | 100.0 | |||

| 2 | Housing condition | ||||||

| a. Non-permanent | 12 | 17.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.000 | Significantly different | |

| b. Semi permanent | 26 | 37.1 | 2 | 2.9 | |||

| c. Permanent | 32 | 45.7 | 68 | 97.1 | |||

| Total | 70 | 100.0 | 70 | 100.0 | |||

| 3 | Clean water service | ||||||

| a. Well | 49 | 70.0 | 1 | 1.4 | 0.000 | Significantly different | |

| b. Collective public water supply | 2 | 2.9 | 4 | 5.7 | |||

| c. Public water supply | 19 | 27.1 | 65 | 92.9 | |||

| Total | 70 | 100.0 | 70 | 100.0 | |||

| 4 | Loan ownership | ||||||

| a. has no loan | 41 | 58,6 | 22 | 31,4 | 0.002 | Significantly different | |

| b. has loan ownership | 20 | 28,6 | 39 | 55,7 | |||

| c . Uncertain | 9 | 12,9 | 9 | 12,9 | |||

| Total | 70 | 100 | 70 | 100 | |||

| 5 | Comfortability | ||||||

| a. Feel Comfortable | 44 | 62,9 | 61,0 | 87,1 | 0.011 | Significantly different | |

| b. feel uncomfortable | 22 | 31,4 | 2,0 | 2,9 | |||

| c. Uncertain | 4 | 5,7 | 7,0 | 10,0 | |||

| Total | 70 | 100,0 | 70,0 | 100,0 | |||

The data on physical assets then analysed with the Wilcoxon signed-rank test to assess the changes before and after the resettlement project over a period of nine years. The significance of the assets is justified by the p-value that is less than the critical research limit (α=0.05). It can be inferred that there is a significant difference between before and after resettlement for five assets: land tenure, housing conditions, clean water service, land ownership and comfortability (see Table 5).

The descriptive statistics of the data reveals significant changes in the conditions of land tenure and housing for the resettled households. Prior to resettlement, 57% of the respondents were living on land with no legal status. This means they were in a vulnerable situation, susceptible to eviction. Around 40% of the settlers had some form of land tenure security, indicating that they had legal rights to the land they occupied. The remaining 3% were in the process of acquiring legal status for their land. After the resettlement process, 97% of the settlers obtained land tenure security. The process was made possible through local government subsidy, which facilitated the purchase of land that conformed to residential uses. The Land Agency of Surakarta City issued land certificates for the households based on a recommendation letter from the Urban Village Office. It took approximately one year to complete the process of land certification.

Concerning housing conditions before resettlement, the questionnaire data reveals that prior to resettlement, a portion of the settlers lived in non-permanent housing (17.1%), indicating temporary structures. Additionally, a significant number of households resided in semi-permanent housing (37.2%), which suggests dwellings that were more durable than non-permanent structures but still lacking in permanence. After resettlement, with the subsidy of IDR 8.5 million provided by the local government, the majority of the settlers (97.1%) were able to construct their own houses in permanent condition, even though the initial subsidized houses were relatively small, measuring 5x5 m2 (25 m2).

Despite the minimum finance provided for housing construction in the early process of resettlement, merely IDR 8.5 million, the resettled households were able to upgrade the condition of their homes over time as their economic capacity increased (Figure 3). As the households' human and financial capital grew, they were able to make improvements.

For clean water provision, prior to resettlement, the majority of households (70%) obtained their water from household wells. A small percentage (2.9%) had access to tap water, indicating a limited number of households connected to the public water supply network. The remaining 27.1% of households had secured the necessary legal documents to gain connection to water networks.

After the resettlement, in the early years, the local government provided a communal water system, which included six units of hydrants for every 20 households. This system aimed to provide water access to the resettled community in a collective manner. Subsequently, the local water utilities (PDAM) extended the water network to the resettlement area, gradually replacing the communal hydrants. By 2018, the water network had covered 92.9% of the resettled households, signifying a substantial improvement in access to clean water services. The head of a neighborhood unit mentioned that clean water services received special attention from the Surakarta Government. This highlights the commitment and prioritization of providing clean water to the resettled community.

“The Surakarta Government gave attention to the water supply since the beginning of the resettlement process…”

Furthermore, Table 6 displays the livelihood assets that were found to be not significantly different before and after the resettlement process. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was conducted to analyze the statistical results, indicating that the following six livelihood assets did not exhibit significant differences: (1) condition of sanitation; (2) condition of road; (3) occupation; (4) skill; (5) income stability; (6) education facility.

For sanitation, the data reveal that before resettlement, most of the resettled households had used the river for their wastewater disposal. The questionnaire shows that 41% of households had disposed of their domestic wastewater straight to the river without any treatment, while 14% had done so to collective wastewater treatment. In the resettlement area, the local government through the local water utilities (PDAM) provided four units of communal wastewater treatment because the land condition cannot accommodate individual septic tanks:

“At the beginning of resettlement, all houses utilized individual septic tanks. However, because the land was semi-solid and not able to absorb wastewater properly, the government through the local water utilities (PDAM) therefore constructed four units of communal septic tanks in 2010…” (The head of the neighborhood unit of Ngemplak Sutan)

Prior to the resettlement, a significant number of households (41%) disposed of their domestic wastewater directly into the river without any treatment. This indicates poor sanitation practices. Additionally, 14% of households utilized collective wastewater treatment, suggesting some level of wastewater management. The rest 45% of them had individual septic tanks for their sanitation system. In the resettlement area, individual septic tanks were not feasible due to land constraints.

| No. | Livelihood asset | Before resettlement | After resettlement | Asymp. Sig. (2-tailed) | Results of Analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of households | Percentage to total households | Number of households | Percentage of total households | ||||

| 1 | Condition of sanitation | ||||||

| a.River for disposal | 29 | 41.4 | 1 | 1.4 | 0.372 | No significantly different | |

| b.Collective wastewater treatment | 10 | 14.3 | 60 | 85.7 | |||

| c.Individual septic tank | 31 | 44.3 | 9 | 12.9 | |||

| Total | 70 | 100.0 | 70 | 100.0 | |||

| 2 | Condition of road | ||||||

| a.Clay | 22 | 31.4 | 1 | 1.4 | 0.089 | No significantly different | |

| b. Concrete block | 23 | 32.9 | 56 | 80.0 | |||

| c.Asphalt | 25 | 35.7 | 13 | 18.6 | |||

| Total | 70 | 100.0 | 70 | 100.0 | |||

| 3 | Occupation | ||||||

| a.Civil Servant | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.4 | 0.213 | No significantly different | |

| b.Private company employee | 15 | 21.4 | 12 | 17.1 | |||

| c. Enterpreuneur | 14 | 20.0 | 14 | 20.0 | |||

| d.Informal Sector | 41 | 58.6 | 43 | 61.4 | |||

| Total | 70 | 100.0 | 70 | 100.0 | |||

| 4 | Adaptation | ||||||

| a.Difficult | 2 | 2.9 | 2 | 2.9 | 0.581 | No significantly different | |

| b. Neutral | 11 | 15.7 | 13 | 18.5 | |||

| c. Easy | 57 | 81.4 | 55 | 78.6 | |||

| Total | 70 | 100.0 | 70 | 100.0 | |||

| 5 | Skill | ||||||

| a.No special skill | 37 | 52.8 | 33 | 47.1 | 0.930 | No significantly different | |

| b.Has special skill but no benefit | 2 | 2.9 | 8 | 11.4 | |||

| c.Has the special skill and benefits from it | 31 | 44.3 | 29 | 41.4 | |||

| Total | 70 | 100.0 | 70 | 100.0 | |||

| 6 | Income stability | ||||||

| a.Increase | 18 | 25,7 | 36,0 | 51,4 | 0.285 | No significantly different | |

| b.stable | 51 | 72,9 | 20,0 | 28,6 | |||

| c.decrease | 1 | 1,4 | 10,0 | 14,3 | |||

| Total | 70 | 100,0 | 70,0 | 100,0 | |||

| 7 | Education facility | ||||||

| a.Far from residential area | 26 | 37,1 | 33,0 | 47,1 | 0.113 | No significantly different | |

| b.medium distance | 15 | 21,4 | 15,0 | 21,4 | |||

| c.Close to residential area | 19 | 27,1 | 17,0 | 24,3 | |||

| d.Others | 10 | 14,3 | 5,0 | 7,1 | |||

| Total | 70 | 100 | 70 | 100 | |||

As a result, the local government, in collaboration with the local water utilities (PDAM), provided four units of communal wastewater treatment facilities for all the resettles. This approach aimed to address the sanitation needs of the resettled households in a collective manner. So, for sanitation behavior, as the resettled households no longer disposed of their waste directly into the river, this signifies a positive change in waste disposal practices.

However, the statistical analysis identifies a decrease in the proportion of households with individual sanitation systems. The percentage decreased from 45% before resettlement to all using communal waste water treatment. Households shifted to utilizing collective septic tanks, which are considered the second level of sanitation provision. It's worth noting that while individual septic tanks are considered the highest standard of sanitation, the communal septic tanks were the best available option given the constraints of the resettlement location.

Regarding roads, the Wilcoxon test shows that road conditions are not significantly different before and after resettlement. This can be understood as the previous location was close to the center of Surakarta City, so asphalt roads were dominant. In the resettled area, which is a new development, accessibility via asphalt roads is limited, but the community has been capable of self-help provision of concrete block roads.

For occupation and adaptation, commonly, the issue of occupational deprivation and occupational adaptation has emerged in resettlement projects. Being displaced due to exile from occupational performance and participation and occupational deprivation are likely implications of the unstable new environment (Suleman and Whiteford, 2013). Loss of occupation after a resettlement project frequently happens in a resettlement area, especially when the location of resettlement is far from the previous settlement, as households have difficulties shifting to new occupations and economic activities. People with access of resources and saving would be easily to cope with and adaptive in a natural hazards (Mutton and Haque, 2004). However, in this resettlement case, the location of the resettlement chosen by the community is relatively not far from their previous location, so the risk of occupational deprivation and of failing to adapt to the new environment has been reduced. Therefore, the insignificant value resulting from the Wilcoxon test is a good sign that the settlers are able to keep their occupation and easy to adapt in the new situations. Insignificant change means that the resettles have not been exiled from their previous occupations and environments.

The transformation of the resettlement area into a new residential development area with basic services can be attributed to the collaborative resettlement process as the process characterized by community involvement considers the perspective of community that working together with the government, in which basic services provision caters the needs of the community, and the transformation of vacant land into living area. The new framework of thinking is the key in collaborative planning (Coaffee and Healey, 2003), which in this case, the Surakarta resettlement Program is able to form the new framework of governance culture in dealing with resettlement project.

Huang and Pai (2015) argue that it is crucial to emphasize not only on physical and economic aspect of resettlement but also social and environment. The case of Surakarta shows that physical assets that improved are clean water, housing condition, land tenure, the communal sanitation system for the wastewater, and the neighbourhood road. Beyond that assets, collaborative process signifies the benefit received by the settlers beyond physical and financial aspect. The significant improved of land tenure combined with the subsidized housing, provided resettled households benefits beyond secure land tenure and own a house. The distribution of certificate that is celebrated through ceremony with the Mayor of Surakarta City, Mr. Joko Widodo, Indonesian current President, signifies the recognition and legal documentation of land ownership for the resettled households. The possession of house and land certificates allows the households to utilize their house and land as collateral when seeking loans from banks or other financial institutions. This indicates that the households have the ability to leverage their new livelihood assets as a tool to further access financial resources.

Moreover, the benefit of the two combinations of housing and land tenure extends further. The interviews indicate that the community was also able to use the loans to develop their business or economic earning opportunities. The obligation to repay the loan encourages the community to work harder and develop their economic activities to boost their financial capacity. The entire cycle creates a hard work culture and the culture to set a future plan.

Participatory approach in selecting location for resettlement is crucial (Uehara, Inoue, et al., 2015). For the Surakarta case, the involvement of community to select a place and resettle together to the same place is able to minimize the sense of dislocation experienced by individuals and promotes a smoother transition to the new neighbourhood. Living with the same neighbours in the resettlement area also allows people to maintain their social connections and support networks. This familiar environment can facilitate the mutual assistance process among community members, for example during the construction of neighbourhood roads. Building a sense of community and fostering cooperation among residents is crucial for the successful development and sustainability of the resettlement area.

Meanwhile, opportunities to keep the previous occupations also relate to low capacity for new skill development or new jobs. The insignificant change indicates that even though the local government provided a training program for the resettled community to improve their capacity for creating job opportunities, most of them have not been able to acquire a new skill and apply for a job in the formal sector, and so the settlers remain in the informal sector. On the one hand, the minimum requirements for adaptation and new skills provide low risk of deprivation, but on the other hand, the settlers have not been able to take advantage of the training provided by the government. This situation explains the resulting insignificant income change as most settlers have kept their previous jobs.

The collaborative method used for resettlement initiatives has an influence that goes beyond just the actual acquisition of property and building of homes. As a result, the settlers experience a greater sense of empowerment and control over their new home. It also helps to create new forms of community culture and government.

The creation of working groups that serve as a conduit between the government and the community aids in the development of a new governance culture. In order to ensure efficient communication, coordination, and cooperation between the two sides, these working groups are extremely important. The governance culture is made more inclusive and participatory by actively including community representatives in decision-making processes. The impacted people and communities could ultimately benefit from increased accountability, transparency, and responsiveness in the resettlement program as a result of this collaborative governance model.

The availability of formal financial systems also has a big impact on how a community develops its culture. By giving settlers access to loans and other financial services, we are enabling them to make plans for the near future. With the ability to invest in businesses that generate revenue or upgrade their housing conditions, people are now more self-assured and motivated to work more and try to better their economic situation. As settlers take advantage of the opportunities made accessible to them through the formal financial system, a culture of fiscal responsibility and entrepreneurship may develop. In this sense. The livelihood assets improved, both tangible and intangible.

The collaborative method used in resettlement initiatives, in general, not only addresses urgent housing and land difficulties but also encourages the growth of new forms of government and community cultures. Settlements can actively build their own futures and contribute to the development and sustainability of their resettlement places by including the community in decision-making processes and giving them access to financial resource.

Conceptualization: W. A., P. R.; methodology: W. A., P. R.; data curation: H. M., E. F. R.; writing original draft preparation: W. A., P. R.; writing review: P. R., W. A.; editing: E. F. R.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of the paper.

This research was funded by Ministry of Higher Education and Research