2023 Volume 11 Issue 4 Pages 150-166

2023 Volume 11 Issue 4 Pages 150-166

What are the impacts of the sacred and spirituality on the architectural design of the Zawiyas? Raised under the influence of Sufism, the zawiya is adopted by brotherhoods at the beginning of their propagation on the lands, in order to honour the memory of a patron saint and preserve the Muslim worship. Considered as a religious institution dedicated to Koranic education and affiliated with a brotherhood, which it is often named after, the Zawiya is frequently designed with reference to the spiritual foundations that it is meant to represent. Today, with the embracing of new socio-cultural and ideological references and the various economic mutations due to state intervention, the zawiyas have lost much of their previously enjoyed notoriety and religious power. Yet, some zawiyas of south-western Algeria have kept some prominence and are still vectors of social practices connected with religious education, despite the ruin-form condition of the ksour. Our hypothesis is that the architectural design of the buildings that make up the Zawiya was not only the product of technical or rational knowledge. We think that the designers would have used a know-how that was devoted to the sacred, to spirituality and Islamic Sufism. In order to verify the validity of our theory, we conducted our study in the zawiya Ziyania in Kenadsa. The analysis process draws mainly on the method of in-situ observation as an important tool to collect the crucial data relevant to the morphological study to find out how this spirituality shaped the material construction of its different buildings.

For reasons of clarity, it seems necessary to go back first to the etymology of the word “sacred”, give a definition, which matches the object of our study, and then focus on the key role of the religious aspect, even on the pre-eminence of the sacred in architectural production. However, we do not pretend to reach a perfect definition of the “sacred” notion, given its complexity. For that purpose, we referred to the definitions given by great sociologists, anthropologists and geographers, such as: Durkheim (1968), Mauss (1968), Meslin (1988), Otto (1969), Moussaoui (2002), Ringgenberg (2009b, 2009c, 2009d, 2009a), Berque (2002).

The Durkheimian school defines the “sacred” as the antonym of “profane”. “Religious”, “venerable” and “holy” are all adjectives often used as synonyms of the term “sacred”. According to Durkheim (1968):

“Sacred things are those which the interdictions (of society) protect and isolate; profane things, those to which these interdictions are applied and which remain at a distance from the first”.

The sacred designates then what is out of ordinary, banal and common things; it is essentially opposed to the profane and indicates the presence of a superhuman sign. All sacred things belong to the separate, intangible and inviolable domain of religion and must inspire fear and respect. For the anthropologist Mauss (1968), the sacred is a substance that can incarnate in a being or a thing; it can also be revealed through an action or a condition.

According to the sociologists’ apprehension, the sacred is a human fact rising from a collective consciousness. Certainly, no manifestation of the sacred takes place in the animal world, whereas most human societies abundantly testify to that. The sacred seems thereby to be the specificity of man:

“It is man, only man that is the measure of sacredness of beings and things because he is the agent of their possible sacralisation” (Meslin, 1988).

The sociological use of the word “sacred” is associated to religion and to the different rites it conveys.

Otto (1969) describes ways to reach an impression of “sacredness” in art, or what he calls “numinous experience”. According to him,

“it is the sublime which represents the numinous with more power”.

He also presents three other direct ways to access the numinous: darkness, silence and emptiness. He introduces here notions of architecture and spaces qualified as “sacred”. This definition indicates that a so-called “sacred” architecture is based on timeless and universal symbols, which appeal to the individual through his cognitive senses, and create in him a particular emotion linked to the unspeakable space.

Moussaoui (2002) defines the sacred as an uncontrollable power, designating a force that acts positively and/or negatively on the course of individuals' lives. Unable to master it, these individuals hope to manage it with a set of devices that can be contracted in the word “Rite” — a social and collective behaviour used against supernatural forces, either to protect oneself against them or to obtain help from them by using ritualized signs: words, gestures, actions, prayers, offerings, sacrifices, etc. (Mansouri, 2011b).

The sacred meant in this article is the one that exists within religion and makes its very essence. It is a positive sacred that is present in worship places and living spaces. To live it fully, it has to take a tangible form diffusing energy and a constant sacredness, and to be shared or transmitted within society where “the religious” proves to be a paramount condition for the manifestation of the sacred.

In our context of study, the religious component and the impact of the sacred are revealed in the Algerian ksour, particularly in Kenadsa. This impact is materialised by the projection of a certain number of spaces and buildings of a purely religious feature. The zawiya, which is a key monument in Islam and a place of fulfilment for popular Sufism, is the symbol of the sacred within the Saharan ksour. Ksour is the plural noun of Ksar, which literally means “castle”. Here it designates a traditional human settlement in the Sahara surrounded by a rampart.

“Zawiya” is a word which takes root in the verb “Inzawa” which means in Arabic “to withdraw, to isolate oneself or to be apart”. It also refers to a place: an angle, a corner, a cell, an oratory …, where people gather, seek comfort and serenity, and pray God through a patron saint. The zawiya, also transcribed zaouiya or zaouïa, is a religious institute including a mosque, meditation and study rooms, and an inn where pilgrims and students can sojourn. It is assigned to spiritual practices and its holy founders are buried there. Basically, a zawiya was a seat of a Tariqa — the path on which the mystic progresses on his way to God. It is the set of divine perceptions Muslims resolutely have to stick to (Mansouri, 2011a) —, where a faithful man called the Wali —a pious worshipper of God who lives a degree of faith higher than that of common people— chose to live in isolation in order to devote himself to meditation. Besides its religious and sacred role, it offers numerous social, economic and political services. It is a center of education and intellectual radiance as well. The zawiya appeared in the Ifriqiyan landscape from the 12th century (Yosr, 2022). In fact, its birth met the need for psychological security and access to the divine. This is how its structure still refers to the link between God, the wali and man (Mircea, 1990).

As for its architecture, we consider that it is definitely linked to cultural, imaginative and spiritual paradigms. It is both science and art. It is science because it requires technical knowledge. It is also physical conformations rising from the art of imagining and guiding architecture through organized thought. For the Ksourian man and by his religious beliefs, the universe is a mere emanation of the divine unity, and each creation is only the reflection of this unity. Thus, any production or physical transformation will obey in all fields, especially in architecture, an order in which mysticism, the imaginary and the spiritual express themselves.

In view of what is stated above, we believe that the zawiya continued to evolve both functionally and architecturally. This functional diversity gives a glimpse on a spiritual experience, which is both individual and collective, allowing social exchanges within a community that finds its ideas and opinions in mysticism and Sufi philosophical thought.

We will thus say that architectural production responds to a relation of concomitance between the plurality of Sufi ritual practices and the mystification of architectural space. To each social or ritual practice corresponds a space devoted to it, and its mystification depends on the nature of the activity and the degree of sacralisation granted to it.

This work is the fusion of two approaches:

To achieve it, we have adopted the “hypothetical-deductive” method, which consists of anticipating answers to questions on specific aspects relating to the subject of our study, from a hypothesis in order to confirm or invalidate it. This method is organized according to the following stages: to formulate a hypothesis for our questioning on the repercussions of the sacred on the architectural production of the Kenadsa Ksar; to experiment and observe in the ground if the facts correspond to our assumptions; then the interpretation of the results to finally return to our initial hypothesis, as shown in Figure 1.

(Source: Givex.com (n.d.) )

(Source: PDAU (Algerian Master Plan of Development and Urbanism)

(Image processed by author)

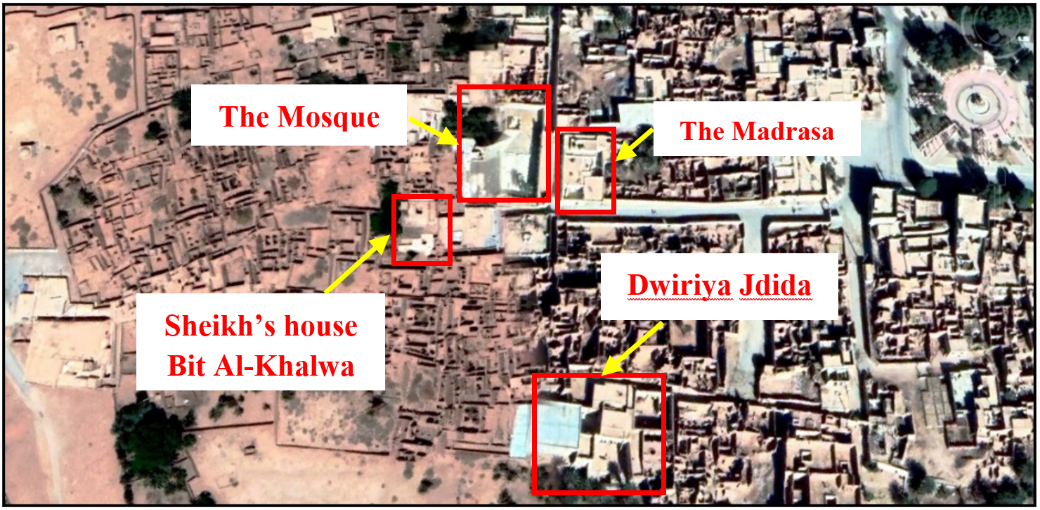

We have opted in the context of this article and as a case study for the zawiya of Kenadsa, which is located in the town having the same name in the wilaya — Fist-level administrative division in Algeria. Since December 18, 2019, Algeria is divided into 58 wilayas, instead of the 48 former wilayas — of Béchar in south-western Algeria (Figure 2). Kenadsa city spreads according to a linear axis punctuated by three main districts: the new city, the colonial district and the old Ksar (Figure 3). The choice of this example is motivated by the fact that this prototype represents a perfect model that is still functional and alive. Due to its Saharan architecture and its historical and spiritual dimension, it can be an excellent object of study. This zawiya was founded in the 17th century by Sidi M'hammed Ben Bouziane. It consists of: the Sidi M'hammed Ben Bouziane mosque, Dar Sheikh, Bit-Al-Khalwa, the Madrasa and the D'wiriya J'dida.

As stated above, its founder is Sidi M'hammed Ben Bouziane, known as Moulay Ben Bouziane. After a long journey in search of knowledge, he returned home and began to build the zawiya, around which the ksar of Kenadsa is edified. Following this event, Kenadsa ksar became, in addition to being a crossroads of commercial and economic exchanges, a spiritual and cultural center that illuminates the whole Maghreb and passed from a mere Saharan city to a real ksourian city (Benaradj, 2020). We find within the zawiya all the holy places as classified by Dupront (1987): Cosmic places represented by all the tombs of the patron saints, historical places like the Madrasa (school), Al-Khizana and Al-Atik Mosque, places of eschatological fulfilment represented by the visits made by the pilgrims who live this experience as an eschatological achievement, and finally places of reign, represented in Kenadsa by the Dwiriyas — a domestic space where the owner's family members live. But its main function is to serve as a guest house (space for reception) for visitors and pilgrims —, a kind of palace where the sheikh of the zawiya settled (Bernadou, 2020), as shown in Figure 4.

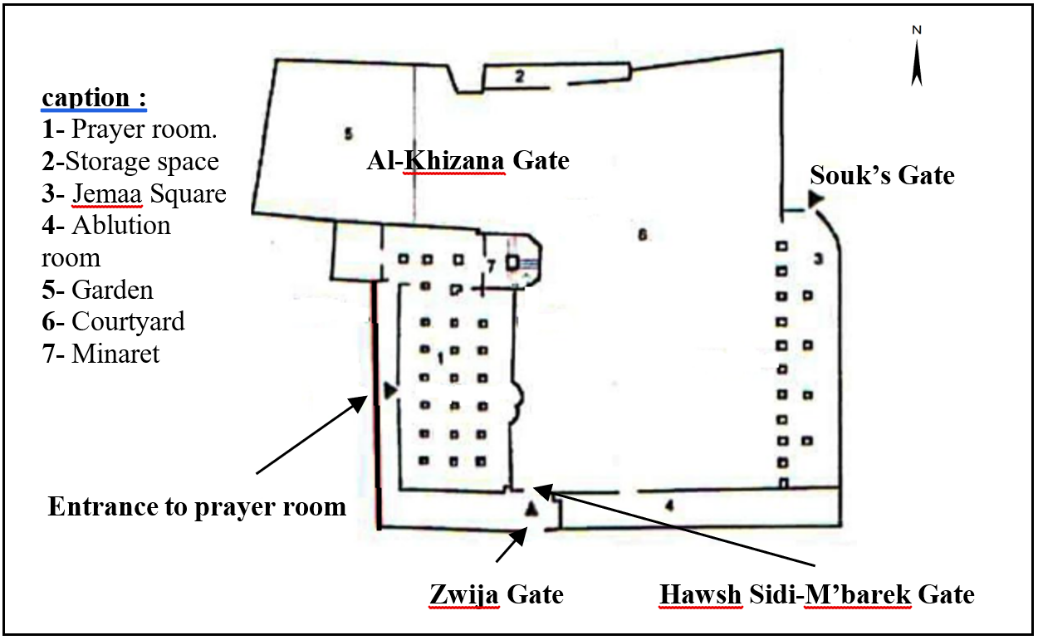

Sidi M’hammed Ben Bouziane mosque is located in the center of the Kenadsa ksar (Figure 5). At the urban scale, the mosque is an Adhan — Call to prayer — instrument thanks to its minaret which is 30 m high. The main access is from the south side through a full-wooden door called Bab Z'wija, the upper part of which is sumptuously decorated and whitewashed, unlike the rest of the fence which has kept its ochre tint. Other secondary accesses exist, one reserved for women and the others bear the name of the space they overlook: Bab —Literally: Door or gate— hawsh-Sidi-M'barek, Bab Al-Khizana and Bab Souk. The mosque is built as a load-bearing wall with mud bricks and wooden floor, palm leaves and reeds.

(Source: BERKANI, A.)

(Source: Makhloufi, processed by author)

The mosque is composed of a prayer room, a minaret, a courtyard, the Jemaa square, an ablution room and a garden (Figure 6). The main axis according to which the spaces are organised is that indicating the direction of the Qibla —It is the divine direction towards the Kaaba, in the sacred Mosque of Mecca as the focal point of Islamic Ummah when praying (Naing and Hadi, 2020)—. The courtyard have been illustrated as a spiritual form in practically all religions around the world. The use of the courtyards offers an intentional contrast between the intense and lively heat of the outside and intimate confinement of the shade and the coolness of courtyard inside (Mezerdi, Belakehal, et al., 2022). The prayer hall has a rectangular shape; it is deeper than it is wide and is composed of six naves and two spans. As support organs, we can discover within the mosque: pillars and two types of broken horseshoe arches. The capital looks like the one in the great mosque of Kairouan and has a relationship with the Syrian Umayyad capitals. As for the Mihrab, it is a niche dug in the wall of the mosque — The function of the mihrab is to indicate the direction of Mecca (the qibla)— and built with the same material as this one. The tombs of the patron saints lean on this same wall. The mosque has two other Mihrabs: one outside, arranged in the central arcade of the Jemaa square, and the other is wooden and serves as an inner separation between the space of prayer and the tombs. At the corner of the prayer hall stands the quadrangular minaret, composed of two towers: the main tower, and the upper one which is surmounted by an ovoid cupola. The minaret has a full central nucleus with a spiral staircase. The external decoration is uniform on the four sides of the minaret and is represented by five-foil blind arches.

Bit-Al-Khalwa and the Sheikh’s house (Dar Sheikh)The two buildings are terraced. They communicate by a covered interior passage. The Sheikh's house is rectangular and has a square patio formed by four columns. The facades are introverted (no exterior openings). Unlike the later buildings, the Sheikh’s house and Bit-Al-Khalwa —Lit. “Retreat room” —are characterized, in terms of decoration, by the simplicity and sobriety of their architecture, which is free of decorative and architectural elements. These are highly spiritual spaces, very visited during Mawlid — The observance of the birthday of the Islamic Prophet Muhammad — festivals. The two spaces are in the image of the Sheikh’s personality because they reflect his Sufi philosophy, his humility and modesty.

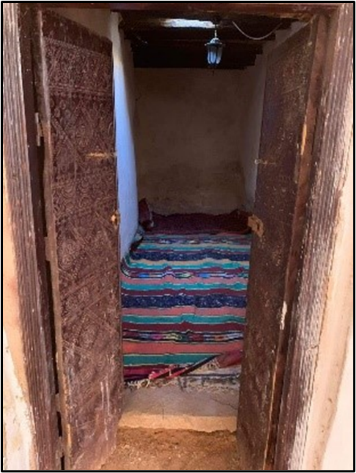

Bit-Al-Khalwa of the Kenadsa zawiya is a small room receiving a light beam from the ceiling and as furniture, a carpet covers the entire floor. It is in this room that the Sheikh of the zawiya isolates himself from the world in order to meditate and worship God (Figure 7). On the other hand, the house of the Sheikh obeys a concentric composition with a centralised open courtyard. The other spaces are symmetrically arranged with respect to a central axis. This geometric order allows a well-balanced deployment of space in all directions.

The analysis of the geometric composition rules of the house revealed that the layout obeys a framed organisation whose basic unit is a 12 m side square. The patio is the element that physically represents this module. Thus, all the spatial structure uses a system of proportions which respects the 12 m square frame. We can then deduce that the final morphology is indeed the multiplication of this basic square unit. In addition, one side of the patio is oriented towards the Qibla. In order to build the generative model, it is simply necessary to follow a certain number of laws, which are: The orientation of one patio side towards the Qibla, the existence of a central space (the patio in the case of the Sheikh's house), respect of the 12 m square frame, and a concession approach: if some constraints impede the 12 m frame, any space lost on one side is automatically recovered on the other (Bekhouche, Bouaouiche, et al., 1991).

The Riad (D'wiriya J'dida)It is a residence whose essential function is the reception of guests. It is also a prayer room and a place of teaching and blessings. It is both a public and a private space. Here is an explanation for houses with the combined functions of home and work (Tutuko and Shen, 2014). The D’wiriya is reserved for notables and their families; it provides during religious gatherings lodging for the zawiya followers. The particularity of the D'wiriya J'dida —Lit. New D’wiriya —is that its typology is a combination of a D'wiriya and a Riad (Palace), because it takes over the function and the spatial organisation of the D’wiriya reception rooms, on the one hand, and opens onto the Riad courtyard containing a fountain and a pond (there is no patio). We can thus say that the D'wiriya J'dida of the zawiya has the function of a D'wiriya and the architectural typology of a Riad. As for its architecture, the D'wiriya J'dida is characterised by the richness of the decorating elements on the walls and the ceiling, and its arcades which offer a diversity of style and ornaments.

Al-madrasa (The zawiya Koranic school)It is an annex of Ben Bouziane mosque, held by an Imam who is responsible for providing completely free education for children of all ages of the Ksar. The program consists of reading the Koran, Islamic law and Arabic grammar. The school is composed of a small courtyard, storage spaces, classrooms and an external staircase leading to the terrace which offers a 360° view of the entire Ksar. As furniture, there is a blackboard hanging on the classroom wall and the floor is covered with handmade carpets called in the local dialect: Braknou. Except the external door which is a slightly decorated, the rest is sober, simple and does not show any ornamentation. The reasons for this choice will be explained further in the article.

Now that the morphological analysis is done, we will expose its results while confronting them with an interpretation test where we will try to locate the important elements that bring testimonies to the divine presence, in addition to a religious, mystical and philosophical understanding of the principle of unity and unified multiplicity, and finally seek answers to the question of the transformation of matter into forms.

Orientation and geographyIn Islam, the orientation to Mecca (the divinely chosen center of the Islamic world) is both a foundation for an ordered geography and a reference to spiritual and sacred symbolism. Whether it is the mosque, Bit-Al-Khalwa or the Sheikh’s House, these spaces are, at the level of the Kenadsa Ksar, all oriented towards the Qibla. This orientation has a cosmic meaning, because the fact of orienting a building towards a divine center means positioning oneself on a divine geographical map (Akkach, 2005). This can also be perceived as a horizontal link with the center of the world (The Kaaba, a stone building in the court of the Great Mosque of Mecca, and the point toward which Muslims turn at prayer. It is also the most sacred Islamic pilgrim shrine) and a vertical link with the celestial center (God). This orientation is an act through which a spatial order is established and tends to organise several religious and/or worldwide spiritual spaces around a central point. It similarly indicates a psychological and spiritual direction, as stated by Ringgenberg (2009b): “…orientation towards Mecca is not only a rite of the body, but also a symbol capable of structuring the thought, the volition and emotionality. By turning towards Mecca five times a day, the Muslim brings evidence through his body to the fundamental orientation (towards God) which must determine his life line and the conduct of his being”. Similarly, this order is perceptible inside the enclosure of the Kenadsa Ksar, where the mosque is the central and unifying point towards which all the paths converge. Through this organisation, the Ksourian man knew how to impose a sort of spatial order by which he established a return of physical diversity to unity, and of the multiple to the single.

The lightThe amazing know-how demonstrated by the Ksourian man is revealed in the skilful way in which he managed to produce a staging under the artistic effects of a natural light, whose main actor is the Ksar, and the scenic space is the oasis environment with its natural decor and architectural product. Indeed, natural light is considered from a functional and constructive point of view as the essential matter; it is even indispensable and complementary to the land matter. The fact of crossing the different paths (Droub) of the Kenadsa Ksar allows the visitor to live an outstanding and surprising experience which lies in the variation and the sequential alternation between dark and luminous spaces. This brings rhythm and liveliness to the exterior area. It is a unique experience, not only visually but also sensitively, spiritually and emotionally. The use and filtering of light is not only a characteristic of exterior spaces but also of interior ones, especially of the Kenadsa zawiya’s buildings, that we have closely considered.

Introversion is the common characteristic of all Ksar buildings. Whether this is done for climatic or privacy reasons, introversion is seen in the lack of openings to exterior spaces, except a few small windows in very specific places. Everything in the Ksar is lived from the inside; it is in the interior that the essential happens. Following our investigation in the zawiya of Kenadsa, we noticed that the action of light worked in three different ways:

In the Ben Bouziane mosqueIn contrast to what usually happens, the windows are rectangular, barred and low (30 cm above the ground). The reason is not only climatic (as a screen against climatic variations) or related to lighting (meeting lighting needs), but also functional, practical and symbolic. The inhabitants of Kenadsa in general and the mosque followers in particular are known for sitting on the ground, so that the light directly illuminates their books. The windows are facing north. The light is direct, very stable and soft; it creates a nice atmosphere during prayer and meditation, while having a contemplative look at the sky (Figure 8).

Here, the relationship to light is totally different. The rooms overlooking an exterior courtyard are opened to light through windows and doors. The internal walls create walls of shadows so that the interior rooms benefit from the day light and the freshness of the courtyard. This creates a sensitive environment and an overtime changing atmosphere (Figure 9).

Here, the play of light is quite impressive. Light comes sparingly from a small slit in the ceiling called: Ain Dar (Lit. the eye of the house), exactly to where it is needed. Light is filtered and dimmed by the use of clay in construction. The lighting intensity varies according to the hours, days and seasons. Inside, we are immediately attracted by this great visual silence which perfectly matches the very tight and very mysterious lighting of the place. Nothing is encumbered because there is no decoration and no possible distraction. Bit-Al-Khalwa is a space which creates silence in all its dimensions, and all the necessary conditions to pray and do mystical work (Figure 10). The passage which connects Dar-Sheikh and Bit-Al-Khalwa is designed for its part in a similar way to the road system of the Ksar. It follows the same rules of alternation between darkness and light. The passage is narrow, dark and low, giving the passers-by a great moment of spirituality, awakening of the senses and prostration, without this being required.

Morphologically, the ksar of Kenadsa shows an organizational paradox: the building is strongly structured following an orthogonal, practical and elementary geometry, whereas the exterior space is organic and structured with narrow and winding streets. The whole is strongly linked and coexists in perfect harmony. The type of quaternary used is square or rectangular. This form evokes stability and resolution of tensions. It embodies the idea of border, totality and immutability. In fact, the quaternary brings to mind the fundamental structure of the terrestrial cosmos and the elements composing all created things (Ringgenberg, 2009c). In most of the Kenadsa zawiya’s buildings, we find a central square (sometimes rectangular) open-air courtyard. This configuration encapsulates a symbolic miniature of the universe. The four sides of the courtyard represent the four columns that support the dome of the sky, which itself serves as a roof for the courtyard. Each building has thereby its own autonomous and self-sufficient world, its own climate, and its own symbolic, matrix and totalizing reality: to stand in a house courtyard, a madrasa or a mosque is like finding oneself in the center of the world, in a domed hall on the scale of the universe (Ringgenberg, 2009d).

The materialThe Ksar of Kenadsa was built at a time when industrial production did not exist in the region, long before the invasion of synthetic manufactured products which are dangerous for humans and for the environment. The builder himself prepares the building materials; he is at the same time the architect, the engineer and the designer. The matter is worked, kneaded and hand-modelled. The experimental part is done by means of observation, touch, taste, experience and above all patience. The relationship to matter is very special because once transformed and materialized, it gives rise to ecological and low energy consuming constructions (Figure 11). The use of the matter is done with care, meticulousness and extreme economy. Here, “everything is transformed and nothing is lost!” This tells us precisely about this sacred and protective aspect that Ksourian man gives to his environment, the only source of raw materials.

It is obtained from the pigments contained in natural substances of organic or mineral origin. Once crushed and transformed into a powder, they are either suspended in binders to be coloured or applied to a wooden or clay surface to give it a colour (figure 12). The use of colours in the architectural decoration of the Kenadsa zawiya’s buildings follows the degree of religiosity and spirituality of the place. That is to say, the more the space is spiritual such as Bit-Al-Khalwa, Dar-Sheikh and the Madrasa, the less it is coloured to avoid distraction. The more the space is meant to host visitors, the more it is richly decorated, as in the case of D'wiriya J'dida. As for the mosque, the dominant colour is green because it is considered as the colour of paradise. This stated, it is almost difficult to find a detailed interpretation of the polychrome decoration, due to the lack of written documents. We, however, learned through our interviews that the choice is often subjective; it is only the reflection of the craftsman state of mind.

It is at door level that the threshold materializes and constitutes an ambivalent frontier between two opposing universes. In our zawiya, the threshold allows a multitude of interpretations and explanations which can be social, religious, psychological or mystical. It symbolizes the passage from the unknown to knowledge (The Madrasa), from the profane to the sacred (the mosque), from the public to the private (Dar-Cheikh), from darkness to light (Bit-Al-Khalwa), or from the apparent to the hidden (D'wiriya J'dida).

• From the unknown to knowledge: The Madrasa is the place of learning and discovering the spiritual dimension of existence. Students receive an education based on the Muslim vision of the person and of human relationships. This place is where they learn to read and write. Its threshold opposes knowledge to ignorance.

• From the profane to the sacred: The door means a symbolic barrier between an impure and transient exterior, and a purified or sanctified interior (It is obligatory to leave the shoes outside). It is a place of submission to God.

• From public to private: It expresses respect for privacy, modesty and secrecy. It materializes a public space reserved for men and work, and a private space reserved for women.

• From darkness to light: Bit-Al-Khalwa is perceived as the space where the soul is spiritualized by prayer and inner sincerity. It gradually becomes transparent. Thus, the soul which was previously opaque becomes the window of spiritual light. The higher the degree of spirituality, the more the veils between man and God vanish.

• From the visible to the hidden: The threshold reveals here a register of social skills such as discretion, humility and modesty. From the outside, nothing suggests the richness and beauty of the house. The signs of wealth are thereby reserved for interior spaces.

The door is also described as an art object. Indeed, this piece of wood is magnified, sculpted and painted in order to beautify the residences and give a better appearance to the door knockers.

The epigraphic and vegetal decoration, the solar motifs and rejection of figurative images

The use of decoration follows the same principle as mentioned above for colour. Human and animal representations are banned from the zawiya buildings, because using them is claiming to be a creator and the equal of God. This is not tolerated in Muslim culture. Embellishment is done with epigraphic and geometric vegetal and solar decorations. Inside Ben Bouziane mosque, epigraphic and geometric decoration is the most used, unlike the D'wiriya J'dida where we find more vegetal and solar patterns. The calligraphy is of Maghreb style; it emphasises these two sentences, motto of Al-Kendousia — Al-Kendousia derives from Kenadsa, the town it is named after — zawiya: "Al-Afia al-Baqia" (Everlasting wellness) and "Wala ghaliba illa Allah" (There is no victor but God). Using this kind of ornamentation attests to the love of beauty and the mastery of geometry and order notions. The use of solar motifs (moon and stars) refers to the symbolism of the sky from which comes the light of heavens and earth (Figure 13).

The relationship with nature: Garden and waterIf the “Kenadser” —the inhabitant of Kenadsa— managed to get adjusted to his environment and to tame it, it is because he knew how to cleverly deal with the geographical and climatic characteristics of his territory. The “Water/ Garden” tandem is the other link which strongly completes, with the buildings, the chain of the Ksourian space, which is representative of an indivisible system that guarantees a perfect balance between man and nature. The relationship with water is a priority and even a vital need. After his settlement, Sheikh Ben Bouziane drilled several sources for domestic and agricultural needs. Given its importance, several architectural supports are built to provide water: fountains, wells, basins for ablutions and irrigation systems (Figure 14). Yet, from the point of view of sacredness, it: “gives life and is a sign of divine mercy; water has a sacred aura” (Ringgenberg, 2009a). In Kenadsa, offering water, digging a well or building a fountain is a commendable act and a symbol of faith and piety. As for the garden, it is perceived as a source of beauty, an image of peace, a space for contemplation and retreat; it is a reproduction of Heaven on earth.

The hermeneutical reading done on the Kenadsa zawiya’s buildings tells us that in any constructive act we find the (however small) expression of the sacred and of the imaginary paradigm. With a keen sense of observation, we realise that nothing happens by chance. It is now obvious that it is imagination rather than technique that is the source of creativity. The Ksourian space is highly influenced by Sufi ideology, it is the reflection of a sacred and spiritual logic: divine unity, beauty and harmony of space, love of art and of the sublime, the attachment to cultural and identity values, and inclination towards austerity, sobriety and ritual life. At the architectural scale, it is seen in the geometric, symbolic, calligraphic, decorative and chromatic work which offers a spatial configuration rich in meaning and in symbolic paradigm that is in perfect harmony with the Kenadsian Muslim spirituality.

The Ksar of Kenadsa was born of the union of several functional and economic elements at a time when it served both as a relay point for the various trans-Saharan caravans and as an eco-systemic order, indicating by that the dense and so complex (but complete) network that the Ksourian man maintains as a gateway to his arid and austere environment. When constructing his ksar, the Kenadsian man knew indeed how to take advantage of the natural resources of his territory while ensuring a better bioclimatic adaptation (relationship to the palm-grove and building materials) in order to face the hard climatic conditions. If this approach allowed the growth of the Ksar, we think that it does not explain, neither justifies by itself the survival of the Kenadsa Ksar to the present day, especially after the invasion of the modern currents, the new ideological references and the economic changes undertaken by the Algerian state. The Ksar owes its longevity to this beating heart which is Zawiya Ziyania Al-Kendousia.

Commitment to religious teaching, to mysticism, to sacred things and to Sufi ideology has had a tangible influence on architectural practice, by instilling a sense and a soul into the physical conformations of the various buildings. In this way, the architecture of the zawiya is in the image of the creative act of the universe on earth and in Heaven. We have tried to demonstrate that any work or structure composing the zawiya buildings of Kenadsa abounds in symbolic, spiritual and religious meanings.

We have come to believe that the relationship of the Kenadsian man to his space and to Saharan nature is at once ecological, technical and mainly symbolic. This attests that the Kenadsa Ksar is an ecumene that the geographer Berque (2002) defines not as a mere anthropized land area but as the relationship of a group to its inhabited space, including the way to design it, to live in and to be inhabited by the space, the way to plan and to be protected by this place. Augustin Berque who has written on the relationship of human societies with their environment thinks that the idea of eliminating the sacred means transforming things into objects and convert the environment into a mere quantifiable space. Hence, the only thing left will be the physical and economic dimension of the place. Ignoring the sacred is taking the risk of denying human existence, which leads to Cosmocide. This fact is observed in architecture and modern urban planning which rely on the technical improvement of human daily life, without considering the environment or the trajection of eco-techno-symbolic ecumenical holds. This is what Berque calls Acosmia which is revealed by the "messy" space and “the landscape killer” (Berque, 2002).

Sociologist Edgar Morin said that man is not a mere technician who manufactures tools, but a Being that cannot live without myths, beliefs and religions. This is actually the case in oasis life where the sacred is neither episodic, nor anecdotal or occasional. It is daily present, accompanying the being as if to provide it with the energy needed to survive in a quite challenging environment. The sacred has been established in these lands; it is a call and a permanent necessity. It even left its mark everywhere on the buildings, on the road network, on the palm-grove and on all that makes up the Ksar. This presence is so strongly felt that it is difficult to examine the ksourian framework without locating the zawiya and the caravan tracks (Bouchareb, 2014).

Conceptualization, L.I. and A.B.; methodology, L.I and A.B.; software, L.I.; investigation, L.I.; resources, L.I. and A.B.; data curation, L.I.; writing—original draft preparation, L.I. and A.B.; writing—review and editing, L.I. and A.B.; supervision, A.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of the paper.

The authors like to acknowledge the brotherhoods of the Zawiya El-Kendousia and all the inhabitants of the Ksar of Kenadsa for welcoming us into their homes.