2024 Volume 12 Issue 3 Pages 176-199

2024 Volume 12 Issue 3 Pages 176-199

Proper Green Infrastructure (GI) management is one method for mitigating heat waves as a results of global warming phenomenon. Several cities have implemented GI management strategies in anticipation of the heat waves occurance. However, most cities have not followed up with efficient GI management. This study investigates the regeneration of successful GI governance by redesigning forms of stakeholder participation by looking at the values of local wisdom in society. This study yielded 235 respondents with a margin of error of 6.5%. The findings were then analyzed using descriptive statistics and interviews with key persons to strengthen the findings. The GI governance movement was renewed by the adoption of the Rowali model, an environmental movement that planted, cared for, and protected trees while sustaining religious and historical traditions as well as social and cultural values as a value to speak with nature. Here, this finding shows that a small income will not affect direct involvement in the management of GI. The successful factor of the Rowali model is the movement is based on historical values, spiritual values and sociocultural values with clear vision on the program and support by the collaboration of public and private sector. The Rowali model encourages more tree care and maintenance than the planting movement, which has received more attention in prior study investigations. This Rowali model supports the finding that the local government should begin delegating greater authority to the community to manage GI. These findings are expected to add to the current body of knowledge regarding GI governance and can be utilized by urban planners, local governments, and urban observers to promote an effective GI governance movement.

Global warming influences climate change, such as heat waves (You, Jiang, et al., 2022). The European heat wave resulted in massive human casualties (Harlan, Brazel, et al., 2006; Mirzaei and Haghighat, 2010). In 2003, the heat wave was responsible for 52% of all deaths in England’s West Midlands (Heaviside, Vardoulakis, et al., 2016). Heat waves have also killed more lives in Australia than any other natural danger (Nicholls, Skinner, et al., 2008). Several Asian countries are also suffering heat waves (Khadafi, 2023), the heat wave claimed the lives of 24,000 people in India (Kautsar, 2023), worst conditions in Bangladesh (CNN Indonesia, 2023a), and also in Malaysia (Iswara, 2023; Pristiandaru, 2023) as well as Thailand (CNN Indonesia, 2023b). As a result, the world suffered huge economic sector losses (Lestari, 2023). Likewise, in urban areas, heat waves have exceeded the threshold (Mccarthy, Best, et al., 2010), thereby causing an increase in Urban Heat Island (UHI) and urban heat temperatures (Coccolo, Kämpf, et al., 2016; Lee, Moon, et al., 2018; Saraswat, Pipralia, et al., 2024; Swapan, Mohd, et al., 2021). In this regard, the United Nations recommends universal and collaborative efforts to mitigate and reduce the effects of global warming (UNEP, 2013).

One way to mitigate heat waves is in the form of proper Green Infrastructure (GI) management (Brown, Vanos, et al., 2015; Gao, Sun, et al., 2015; Helletsgruber, Gillner, et al., 2020; Morakinyo, Ouyang, et al., 2020; Sumaryana, Buchori, et al., 2022). Appropriate GI management policies and strategies can build resilient cities in dealing with climate change and disasters and make cities more comfortable (Byrne, Lo, et al., 2015; Rayana, Gruehn, et al., 2021; Schiappacasse and Müller, 2015). Several cities, including Andalusia City in Spain, have implemented GI management programs in anticipation of the potential of heat waves (Caparrós Martínez, Milán García, et al., 2020), Baghdad City (Abdulateef and A. S. Al-Alwan, 2021), Singapore and Berlin, Philadelphia, Melbourne and Sino-Singapore Tianjin Eco-City (Liu and Jensen, 2018). The strategic role of GI benefits, it turns out, is not matched by effective GI management.

The ineffectiveness of GI governance, such as the lack of synchronization between the planning and management of government and community actors and the private sector (Harrington and Hsu, 2018). There are several other findings indicating the ineffectiveness of GI governance, such as the weak understanding of GI by planners and policymakers (Matthews, Lo, et al., 2015), only 50% of respondents in Yogyakarta, Indonesia, have a proper understanding of GI (Pratiwi, Fatimah, et al., 2019) and the public’s ignorance of the importance of GI benefits (Derkzen, van Teeffelen, et al., 2017). Previous scientific publications regarding the GI of 41% do not clearly define GI (Matsler, Meerow, et al., 2021) and put more emphasis on the diversity of benefits provided by GI (Andersson, McPhearson, et al., 2015) without considering the synergy of substation management for different urban characteristics (Sussams, Sheate, et al., 2015). Poor GI governance can result in implementation difficulties. Governance and GI concerns are always directly tied to people’s lives (Demuzere, Orru, et al., 2014; Hansen, Rall, et al., 2017), so the existing GI governance gaps lead to ineffectiveness of its benefits in mitigating heat waves (Sussams, Sheate, et al., 2015; C. Wang, Z. H. Wang, et al., 2021).

In Temanggung, Indonesia, less-than-optimal governance of GI happens as well. Previous studies discovered a 268% increase in UHI in the 2013-2020 timeframe, which was caused by poor GI governance (Sumaryana, Buchori, et al., 2022), where the UHI threat can cause health problems and environmental degradation (Arghavani, Malakooti, et al., 2020; Heaviside, Vardoulakis, et al., 2016; Lee, Moon, et al., 2018; Saraswat, Pipralia, et al., 2024; Surni, Riniwati, et al., 2024; Swapan, Mohd, et al., 2021; Zainal, Fadzil, et al., 2024). Other studies in Temanggung discovered an expansion in the wood processing company using raw materials from yearly tree plantings, resulting in diminished tree stands and promoting in situ urbanization (Wijaya and Buchori, 2022). Increasing in-situ urbanization encourages environmental degradation (Buchori, Rahmayana, et al., 2022).

Effective GI governance can address the impacts of global warming and climate change on an urban scale (Byrne, Lo, et al., 2015; Harrington and Hsu, 2018; Ramyar, Ackerman, et al., 2021), become one of the solutions to overcome urban environmental problems (Chaffin, Garmestani, et al., 2016), the key to successful implementation and sustainable management (Bartesaghi Koc, Osmond, et al. 2017). Effective GI governance is characterized by the involvement of various stakeholders, which can have a positive impact on the social, economic and environmental sectors (Ibrahim, Bartsch, et al., 2020; De Sousa, 2014), integrated and focused on ensuring public interest and support (Derkzen, van Teeffelen, et al., 2017; Hasibuan and Sulaiman, 2019). The success of a city program depends on its governance (Gray, Laing, et al., 2017), so GI governance must be integrated for urban sustainability (Rayana, Gruehn, et al., 2021). Understanding GI implementation preferences assists urban planners in developing successful policy responses (Derkzen, van Teeffelen, et al., 2017), in the GI control stage adapted to the capabilities of the city (Cousins and Hill, 2021).

Previous studies have discussed the benefits of GI (Byrne, Lo, et al., 2015; Liu and Jensen, 2018; Miller and Montalto, 2019; Rayana, Gruehn, et al., 2021), related to GI implementation, challenges, and financing (Ferreira, Sykes, et al., 2009; Steadman, Smith, et al., 2023). In contrast, the discussion related to sustainable GI governance with design forms that are oriented towards the potential for local sociocultural strengths is still limited, even though this is the key to the success of GI implementation and management (Ibrahim, Bartsch, et al., 2020; Matthews, Lo, et al., 2015). For this reason, further study related to GI (Nhlozi, 2012) suggests further study related to political and social actors in the management of GI and the need for more effective GI management. Here, the growth of activity patterns based on participation and local wisdom shapes regional potential in infrastructure planning. Therefore, this study aims to explore the renewal of sustainable GI management by designing based on urban local wisdom values through a qualitative approach based on Focus Group Discussions (FGD) and interviews with local communities and key actors.

Benedict and McMahon (2002) defines GI as an interconnected network of green spaces that protects the values of natural ecosystems, their functions, and the associated benefits of ecosystem services. GI is an effort and approaches to maintaining a sustainable environment through structuring green open spaces and maintaining natural processes that occur in nature such as the rainwater cycle, soil conditions, and surface runoff (Widyaputra, 2020), a network of interrelated green spaces that together make ecosystems viable for society (Lafortezza, Davies, et al., 2013). GI, in between, is like a linear garden as a typology of green space (Bartesaghi Koc, Osmond, et al., 2017), planned and managed to positively impact society (Saing, Djainal, et al., 2020).

City parks, urban canals, woods and rural parks, town squares, lakes, main river recreation places, agricultural land, and Waste Final Processing Sites are examples of green infrastructure characteristics in urban areas (EEA, 2011). In general, green infrastructure takes two forms: (1) areas (hubs) that serve as the focal points of green areas such as parks, nature reserves, wildlife reserves, tourist parks, hunting parks, cultural reserves, botanical gardens, forestry and agriculture cultivation areas, environmental parks, and urban forests, and (2) pathways/networks that connect green areas (Damayanti, 2019).

GI governance challenges can be grouped into several, namely: objectives and design, institutional and political system, communication and collaboration, and legal framework (Ibrahim, Bartsch, et al., 2020). Constraints faced and the need for integration in GI implementation, namely management approach, access to resources, public perception, politics and technical expertise (Keeley, Koburger, et al., 2013), while Gerlak, Elder, et al. (2021) show that the various actors and frameworks provide space for various policies in the management of GI. Without effective stakeholder engagement, GI governance can lead to institutional uncertainty in terms of roles, priorities and responsibilities (Ibrahim, Bartsch, et al., 2020)

GI implementation is constrained by management approach and access to resources, public perception, politics, and technical expertise (Keeley, Koburger, et al., 2013). Public support and opinion are needed to manage GIs by conducting sociocultural assessments, community ideas and concerns about climate impacts, GI benefits, and willingness to pay (Derkzen, van Teeffelen, et al., 2017). According to Staddon, Ward, et al. (2018), implementing effective GI governance includes standards; regulation; socioeconomic factors; financial capability; and innovation.

Stakeholder EngagementThe necessity for multi-stakeholder engagement is a challenge for green infrastructure governance (Ibrahim, Bartsch, et al., 2020), and including full community involvement through local community culture will be more optimal in GI management (Conway, Ordóñez, et al., 2021). Household perceptions of GIs help increase public participation regarding the management of urban GI (Barau, 2015) because the community has a significant influence on green innovation (Shahzad, Qu, et al., 2020). Private synergy through corporate social responsibility significantly influences green innovation (Shahzad, Qu, et al., 2020). Non-governmental local political leadership is influential in the management of GI (Harrington and Hsu, 2018), so it will be more diverse to provide space in GI management (Gerlak, Elder, et al., 2021). GI planning and implementation steps are adjusted to the capacity of the city (Cousins and Hill, 2021), so a GI control plan is also needed (Hopkins, Grimm, et al., 2018).

Government policy is the driving force for GIs, and the government’s role as coordinator studies and understands green infrastructure at the national, regional and local levels (Harrington and Hsu, 2018), this is necessary to build cities that are resilient in the face of climate change (Rayana, Gruehn, et al., 2021). To realize a resilient urban ecosystem, periodic monitoring is necessary through measurable indicators of the performance and effectiveness of GI governance (Pakzad and Osmond, 2016). It is necessary to manage urban space that pays attention to aspects related to urban green space for ecological protection, including green spaces and parks (Chen, 2021) and GI benefits (Chang, Lin, et al., 2021).

GI management in the future to ensure alignment with the public interest (Hasibuan and Sulaiman, 2019), by conducting sociocultural assessments, community ideas, and concerns about climate impacts, benefits, including willingness to pay (Derkzen, van Teeffelen et al., 2017). The importance of community and stakeholder involvement in GI management (Baptiste, Foley, et al., 2015; Nehren, Dac Thai, et al., 2016; De Sousa, 2014) and to gain public trust, it is necessary to pay attention to community opinion regarding its management (Derkzen, van Teeffelen, et al., 2017).

Indonesia is one of the three countries with the largest biodiversity in the world, therefore, it contributes to global carbon emissions and serves as the world’s lungs. However, Indonesia has a track record of causing substantial environmental damage. Environmental costs in Indonesia from environmental damage, ecosystem loss, and natural resource depletion totaled Rp. 915.11 trillion in 2010, accounting for 16.36% of the NDP or 13.33% of GDP (Pirmana et al., 2021). With its abundant biodiversity, Indonesia cannot escape the threat of the recent heat wave (Afkar Aristoteles Mukhaer, 2023).

Temanggung Regency (Figure 1), like many other cities in Indonesia, has experienced an increase in the UHI phenomena, causing heat discomfort for its population (Sumaryana, Buchori, et al., 2022). On the other hand, the local government will expand the industrial area through changes to the Regional Spatial Plan (RTRW) of the Temanggung Regency for 2022 – 2042. Urbanization will result in changes in land use, which, if not adequately managed, will have an impact on environmental degradation (Buchori, Rahmayana, et al., 2022; Dewa, Buchori, et al., 2023; Sejati, Buchori, et al., 2020; Sumaryana, Buchori, et al., 2022).

The target of this research survey is the residents of the urban area of Temanggung (N), with a population of 78,824.00 people (Dindukcapil, 2022) (Figure 2). The Slovin formula is used in this study to determine the number of samples as survey respondents (Tejada, Raymond, et al., 2012):

n = N/(1 + (N*eᶺ2)……………………………………(1)

where, n = sample size, N = population size with a margin of error using data e = 6.5%, so that n is obtained by 235 respondents. For the survey results to describe real conditions, this study also used a clustered random sampling technique to spread the sample evenly in the study area to 22 sub-districts/villages (Figure 3). The results are processed using descriptive statistics to formulate a novelty according to the research objectives.

This research was carried out in several stages, with the first stage of the survey conducting a Group Discussion Forum (FGD) on June 16 2022. This FGD aimed to map respondents, formulate question formulas that would be explored, and listen to the community’s GI problems, as Demuzere, Orru, et al. (2014) suggested. The second stage of the survey was conducted directly to respondents in two sessions, namely the first session was in the form of a pre-test, as suggested Munn and Drever (1989), with interviews of key figures from elements of local government officials related to GI management, community and religious leaders, academics, private entrepreneurs and media activists on April 13 - April 17 2023, intending to test the suitability of the survey tools and the accuracy of the questionnaire, as suggested (Munn & Drever, 1989), the result is a refined questionnaire.

The second survey session was to collect detailed data by interviewing using the Google form on April 25 2023 - May 4 2023. The questionnaire framework is divided into 6 parts. The first part is an explanation of the aims and objectives of the research, and the second part is related to opening questions to find out the profile of respondents, related to knowledge and assessment of existing green infrastructure, as well as related to governance and suggestions for managing green infrastructure. Some of the questions posed are open and closed and have a Likert scale, allowing this study to make comparisons between questions.

The third stage was in the form of deepening the answers to the questionnaire, which was carried out on May 8 – May 17 2023, with detailed interviews with key figures. Key figures were taken from community and religious figures, government elements, volunteers, the private sector, academics and mass media figures. They were selected from each element based on input from their organization. This uses a purposive sampling method with the snowball technique, namely respondents who were interviewed and recommended other respondents with relevant knowledge. We asked them about green infrastructure, the tree planting movement, the figures and elements that have the most role in the GI movement, how much they are concerned about climate change and what form they are willing to take if asked to participate directly. This interview also seeks to discover what local wisdom can drive more effective GI management. The answers from these respondents were used to minimize the bias of the answers to the questionnaire survey results.

According to the study’s findings, 58% of respondents were adults, 60% were female, and 58% had a college education. A length of stay question was asked to assess respondents who know the socio-culture in their place of residence, and 78% said they had lived at the study site for more than 10 years, and 51% said their residence had local wisdom related to environmental management, such as community service with residents to plant and care for trees or gardens. Table 1 shows the complete results of the respondents’ attributes.

| Description | Findings |

|---|---|

|

Age Groups Teens Elderly Adults (26–50 Years) |

25 % 17 % 58 % |

|

Gender Female Male |

60 % 40 % |

|

Education Diploma/Bachelor Degree/Master Degree Secondary school Primary school |

58 % 35 % 7 % |

|

Duration of stay/ residency >10 Years > 5 -10 Years < 5 Years |

78 % 12 % 10 % |

|

Environmental management and local culture Available Unavailable |

51 % 49 % |

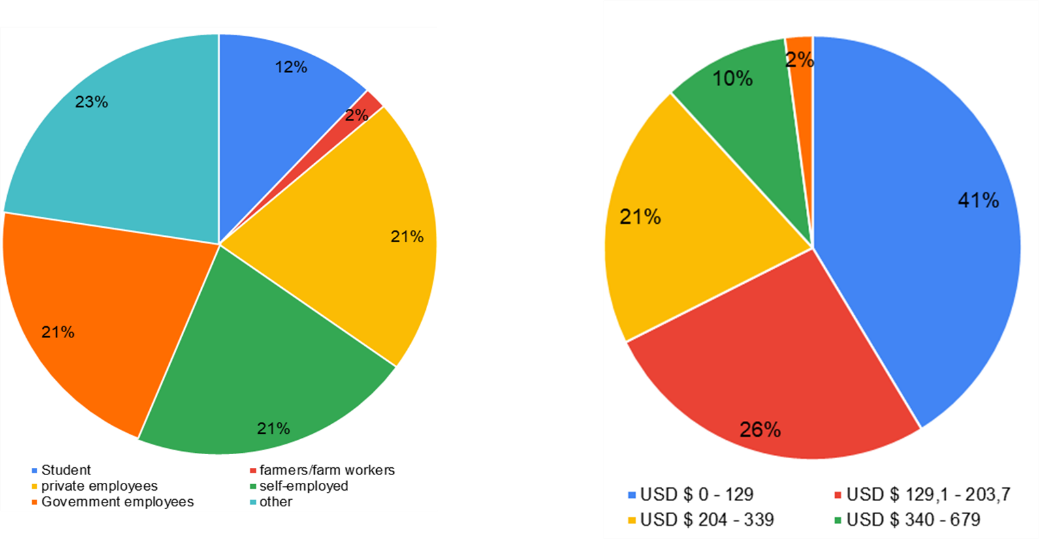

In terms of family income, described in Figure 4, it was found that 41% of respondents had incomes below the Minimum Regional Wage (UMR) set by the government for 2023 or <Rp. 2.1 million (142.65 USD $) per month, while those whose income is equivalent to UMR up to Rp. 3 million (203.75 USD $) per month at 26%. By being dominated by respondents with non-permanent jobs and whose income is still below the minimum wage, it can be assessed how much they care about GI management. In the other hand, the family income does not affect the local community to contribute managing the GI.

Table 2 explains the respondents’ comprehension of the functions and objectives and their involvement in GI governance.

| No | Questions | Answer Indicator | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hear the Term Green Infrastructure | Have ever | Never | ||||

| 58% | 42% | ||||||

| 2 | Main Functions of Green Infrastructure | Natural sustainability | Aesthetics | Economy | |||

| 91% | 8% | 1% | |||||

| 3 | Direct involvement in GI conservation activities | Have ever | Never | ||||

| 74% | 26% | ||||||

| 4 | Forms of Direct Involvement in GI Governance Activities | Tree Planting | Socialization | Coordination meetings | Providing Funding Assistance | Other | |

| 65% | 17% | 8% | 5% | 5% | |||

| 5 | Main Reasons for Directly Participating in GI Governance Activities | Concerns About the Climate Crisis | Local Government Programs | Activities of Other Organizations/ Institutions | Organizational Internal Activities | Personal Initiation | Other |

| 43% | 15% | 14% | 13% | 12% | 3% | ||

| 6 | Main Obstacles in GI Governance Activities | Inadequate Human Resource Skills | Facilities Limitations | Funds Limitations | Other | ||

| 44% | 29% | 22% | 5% | ||||

| 7 | Readiness to Participate in Green Open Space Conservation and Maintenance Activities | Power | Thought | Power, Thought | Fund | ||

| 52% | 23% | 19% | 6% | ||||

Table 2 shows that the community’s understanding of GI is good enough (58%), and most of them understand its main function (91%). A basic understanding of GI and its functions led the community to be directly involved in GI management by 74%, with the majority choosing to plant trees by 65%. Community understanding and involvement in GI management due to concerns about the climate crisis (43%) compared to just following government programs (15%).

Green Infrastructure Conditions and GovernanceRespondents preferred a Green Open Space (Alun-alun) in the city center (35%), with only 17% preferring an urban forest. Figure 5 depicts how the assessment is related to GI issues in metropolitan locations.

From Figure 5, respondents considered that green open space and road protection trees were of good quality >50%, while people who felt comfortable enjoying GI were up to >80%. Meanwhile, to explains the effectiveness of stakeholders’ role in the successful management of GI, is explained in Figure 6.

Figure 6 shows that the role of GI management, which includes the government, business sector, academia, mass media, and the community, is a variable in the question to respondents to determine the dominant and decisive players in GI management. 91% of respondents regarded the government’s role in GI management as excellent to moderate. Compared to other sectors, private players are thought to contribute the least to GI management (Figure 6).

Furthermore, when it comes to GI Governance, a main figure is considered to have the most important function in advancing the community. The results suggest that religious and community leaders are most closely followed by the community in managing GIs (Figure 7). Regarding the most successful communication route for rallying the community, as much as 45% preferred religious informal communication (Figure 8).

During the process of interviews and field observations, it was discovered that a neighborhood in Temanggung City known as Dusun Bendo had a unique approach to GI care. This region is part of an urban green open space, contains a clean water source known as Rowali, and is surrounded by shady trees, including the unique Bendo tree (Artocarpus elasticus), whose historical name was officially named Dusun Bendo in state administration (Figure 9).

Previously, some of these residents illegally occupied land for residential homes for generations with a population of 111 people. Then in 2020, based on joint movement and public awareness, carry out independent relocation by dismantling the house where he lives (Figure 10) the aim is to restore the function of urban green open spaces and protect springs.

Figure 10 describes the process of demolishing residents’ houses independently with cooperation between parties to restore the function of the green area. Figure 11 describes the spiritual activity in the form of “Nyadran” as a communication movement with nature that the Rowali people carry out regularly. Figure 12 and Figure 13 shows the historical elements of the community maintaining rare trees that have historical value because the name of the tree is used as the name of the regional hamlet and documents the development of the tree. Furthermore, the authors of this movement named the Rowali Pattern (using the name of the spring in that place). The research results in this area, hereinafter referred to as the Rowali Pattern, found the characteristics of GI management as shown in Table 3.

Figure 10 describes the process of demolishing residents’ houses independently with cooperation between parties to restore the function of the green area. Figure 11 describes the spiritual activity in the form of “Nyadran” as a communication movement with nature that the Rowali people carry out regularly and regularly. Figures 12 and Figure 13 shows the historical elements of the community maintaining rare trees that have historical value because the name of the tree is used as the name of the regional hamlet and documents the development of the tree. Furthermore, the authors of this movement named the Rowali Pattern (using the name of the spring in that place). The research results in this area, hereinafter referred to as the Rowali Pattern, found the characteristics of GI management as shown in Table 3.

| Factors | Findings of the Rowali Model |

|---|---|

| Early Initiation | Society and government as fasilitators |

| Key Stakeholders | Community and religious figures |

| Background | The community really understands the purpose of the program, to protect urban green open spaces and springs, so they are willing to take part in the independent house demolition program (Figure 10) |

| Local wisdom values |

The community has local wisdom values: Historical value: Rowali trees and springs are part of the history of the settlement. It was proven that the name of the Bendo village was taken from the name of the tree (bendo tree). The community maintains the trees and documents their progress (Figure 12). Meanwhile, the name of the Rowali spring was used as the name of the village at the Rukun Warga level Spiritual value: the “Nyadran” ritual is carried out, which is a joint celebration as a form of communication between the community and the nature of Rowali. These activities are carried out routinely, on a scheduled basis, and for generations, as part of intergenerational education (Figure 11). Sociocultural Values: The community regularly organizes cultural arts activities at the location, carries out activities that are clean for the environment and have a culture that does not damage Rowali’s nature. |

| Economic Value | The community understands the economic benefits that will be realized in the medium and long term through growing asset values, and will be directly involved in the Rowali area’s structuring. |

| Private Participation | The community receives CSR directly through banking subsidies for land purchases. |

| Future overview | The community is given an outline of the program’s future sustainability. |

| Involved parties |

Government: as the initial facilitator and initiator of the program, as well as program synergy Society: Willingness to contribute manpower and funds Private: Banking provides CSR to the community Universities: Involved in providing academic program input Mass Media: providing broadcasting and reporting via local TV and radio |

The findings of GI governance patterns were further classified based on the results of interviews with respondents and observations at the study sites, as shown in Table 4.

| Comparative variable |

GI Governance findings (Y) |

Rowali Model GI Management Findings (Z) |

|---|---|---|

| Community participation in the form of energy and thoughts, funds | √ | √ |

| Participation of stakeholders | √ | √ |

| Initiated by Government and Community Figures | √ | √ |

| Communities involved in the program receive personal economic benefits and can project their benefits in the medium and long term | - | √ |

| The program is led by community figures who are elected by the community | - | √ |

| The process of socialization and continuous learning to convince the community | √ | √ |

| Understanding of the negative consequences if the program is not implemented | √ | √ |

| The community is aware that climate change is endangering the environment. | √ | √ |

| The community directly accepts CSR | - | √ |

| Has long-term investment value that the community can calculate | - | √ |

| In the future, the community will have clear vision of the program | - | √ |

| The movement is based on historical values, spiritual values and sociocultural values | - | √ |

(√): there is activity (-): no activity

Source: Author (2023)

The results revealed that the age range of 26-50 years (79%) dominated the 74% of respondents directly involved in the GI management movement (Table 2). These findings support prior research findings that age is associated with the amount of participation (Hadi et al., 2014). Meanwhile, 57% of women are directly involved in the GI movement, indicating that women are more interested in GI management. These two findings contrast with prior findings in Rotterdam, Netherlands, especially the relatively young age and representation of women in GI management participation (Derkzen, van Teeffelen, et al., 2017). GI governance will be more effective at this level if it focuses on adults, women, and individuals with a higher or secondary education.

While the respondents who were directly involved, when viewed from the length of stay, it was found that 84% had lived > 10 years at the study site, which of course understood the environmental conditions. An understanding of environmental conditions is needed to see local wisdom in their area and 51% of respondents stated that there is a local culture related to the environment in the form of maintaining trees and plants, maintaining springs through regular community service. These results are in accordance with previous findings that local culture can encourage better GI management (Conway, Ordóñez, et al., 2021). The income profile of respondents who are directly involved in GI management is below US$ 203.75 per month, which is 67%. This finding shows that a small income will not affect direct involvement in the management of GI, which is different from what Derkzen, van Teeffelen, et al., (2017) conveys that financial contribution is important in GI management. Respondent participation of 95% stated their readiness to provide energy and thoughts to be directly involved in GI management, this result shows something different from the research (García-Lamarca, Anguelovski, et al., 2022), stating the limitations of participation if financial conditions are low.

The limitation of donating funds from the public (5%) is the same as research in Oxford England in the form of low public awareness regarding GI financing (Steadman, Smith, et al., 2023). To overcome these weaknesses, it is anticipated by optimizing the willingness of the community to contribute their energy and thoughts by setting aside the amount of the contribution of funds (Table 2). Related to this, a solution is sought through private assistance according to suggestions (Staddon, Ward, et al., 2018) that the common financial mechanism for GIs is Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). In the Rowali pattern stage, CSR from the private sector is received directly by the community so that it is more transparent and it is found that the community will be better prepared to contribute funds if there is a budget shortage.

Effective Stakeholder DesignIn Table 2, as many as 91% of respondents understand the main function of GIs related to nature conservation and sustainable life, with people preferring to plant trees (65%). These findings match the results of studies in Toronto and Philadelphia that community participation is more dominant in tree planting (Conway, Ordóñez, et al., 2021). This opinion is supported that urban communities want more green plants, especially trees (Klemm, Heusinkveld, et al., 2015). In this case the GI Governance movement is not only stuck in the spirit of planting trees but more importantly ensuring its sustainability. In the Rowali pattern, there are things that are more unique, namely that the community has a belief in the historical value of the trees in their area, it is proven that the name of the hamlet area comes from the name of the tree and the community itself documents the growth of rare trees, this is in line with the opinion that GI management is in accordance with local preferences and local content (Hsu, Lim, et al., 2020).

The main reason for being willing to take part in the conservation movement is because it is dominated (43%) by people’s concern about the climate crisis which will bring disaster, as the previous findings show that people are concerned about climate change (Derkzen, van Teeffelen, et al., 2017) and respondents believe that climate change will be economically disruptive (Byrne, Lo, et al., 2015). Communities have a great desire to contribute to the GI movement (74%), but realize that the GI movement is still constrained by technical capabilities (44%), so that regular training is needed for the community, this is in line with technical expertise in GI management is still an obstacle (Keeley, Koburger, et al., 2013). This series of findings that GI management will be successful if there is an understanding of the community’s function of GI so that it creates a spirit of contribution as well as collaboration with the spirit of planting and protecting trees.

Modeling Sustainable GI GovernanceThe combination of performance between stakeholders from various stakeholders (Figure 4) is the main factor driving GI management, this is in line with previous research that various actors and frameworks are needed in GI management (Gerlak, Elder, et al., 2021; Ibrahim, Bartsch, et al., 2020), collaboration with various interests and organizational backgrounds (van der Jagt, Smith, et al., 2019; Lubell, 2013; De Sousa, 2014). It was found that the main stakeholders of the GI governance movement were led by community figures (Figure 6 and Table 4), and in the Rowali model, these results are consistent with the findings (Derkzen, van Teeffelen, et al., 2017; Shahzad, Qu, et al., 2020), that community leaders should lead an environmental movement with local political leadership. Apart from requiring leadership from the community, modeling of GI governance is also needed to support its sustainability. Modeling as the results of research findings combined with existing theories, led to a sustainable pattern of GI Governance, as shown in Figure 14.

The Five Rowali Model (Figure 14), are present to ensure sustainable GI governance. The first pattern requires a balance of economic and ecological benefits from the benefits of GI management, so that the community feels that GI is part of their life and can ensure their future. The findings are in line with the opinion (Hasibuan and Sulaiman, 2019) GI management in the future must guarantee the public interest. The second pattern describes leadership that comes from community figures, to ensure the sustainability of tree protection, this is according to suggestions from (Coletti and Bally, 2023; Harrington and Hsu, 2018), namely the need for local non-governmental leadership in supporting GI governance, as well as reducing local government involvement. These findings and Rowali’s model differ from what was conveyed (Breen, Giannotti, et al., 2020) that 47 publications in reputable journals, concluded that the local government led the initiative of the GI movement as the main actor. The third pattern requires transparency of management and transparency of program objectives so that the community becomes part of the subject, not the object, in the management of GI governance. This opinion supports the results of previous research, namely the need for adaptive governance to optimize the utilization of GI (Hsu, Lim, et al., 2020).

The fourth pattern explains the need for the synergy of 5 elements like in Rowali, namely, the community as actors, the government as regulator and supervisor, the private sector as CSR assistance providers, the mass media as socialization media and elements of academics as scientific assistance, this is in line with the findings of (Baptiste, Foley, et al., 2015; Nehren, Dac Thai, et al., 2016; De Sousa, 2014), that the involvement of all parties in GI management is required. The choice of community-based communication channels is in accordance with the findings (Figure 6 and Figure 8) that effective communication of GI management through fostering religious channels and community leaders is in line with the opinion (Ibrahim, Bartsch, et al., 2020) and related to informal communication for effective GI governance (Conway, Ordóñez, et al., 2021; Harrington and Hsu, 2018; Shahzad, Qu, et al., 2020). The pattern of these five models is that a movement for GI governance, especially sustainable management of trees, must have historical, spiritual, and sociocultural values (Figure 11, Figure 12, Figure 13), because trees are considered one of the most prominent GI features (Drury, 2018). The research finding that trees must contain historical and spiritual values is a complementary part of the theory that has been developed so far, which conveys that the management of GIs or trees has significant cultural and heritage meanings for local communities (Conway, Ordóñez, et al., 2021; Edwards, 2011; Hasibuan and Sulaiman, 2019).

This research investigates how GI governance can be carried out more effectively and sustainably to mitigate climate change, control heat waves, and make cities more comfortable. GI governance becomes more important because of the strategic role of the value of benefits and functions. It was found that there were many ineffective GI management that resulted in sub-optimal management of GI. The study results showed that the GI governance movement would be more effective if it targeted the adult population, involved more women’s representation, and optimized the academic community as folklore.

The effectiveness of GI governance is through optimizing the willingness of the community to contribute their energy and thoughts regardless of the amount of their income. Increased understanding of GI governance through a more massive campaign movement, driven by religious leaders and the local community who are self-selected by their group, driven by local political figures with effective communication channels through religious organizations. The GI Management Movement through the 5 Rowali Patterns implies that GI management must pay attention to a balance of economic and ecological benefits, led by the community itself, transparency in program management and objectives, synergy and having spiritual values, historical values and sociocultural values.

This research provides several recommendations for urban planners, observers, and local governments as executors of GI governance activities. The local government must be willing to let go of its dominance to provide greater opportunities for local community leaders to lead the GI Movement. Private contributions in the form of CSR for managing substations must be submitted directly to local community organizations, and the government returns to its function as supervision. Communities are given wider opportunities related to the exploration of spiritual values, historical values and sociocultural values in the movement to care for or plant trees as GIs. Further research is needed relating to the economic calculation that will be received by the community directly related to GI benefits, such as the portion of carbon sales.

Conceptualization, H.S. and I.B.; methodology, H.S.; Analysis, H.S.; Draft writing, H.S.; Reviewing, I.B. and A.W.S.; Editing, I.B. and A.W.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

There is no potential conflict of interest.

The authors wish to thank the Ministry of Education, Culture, Research, and Technology for funding this research in the scheme of National Competitive Applied Research (PTKN).