2024 Volume 12 Issue 4 Pages 181-201

2024 Volume 12 Issue 4 Pages 181-201

This study examines the impact of private ownership and management of public spaces in Jakarta on its quality of publicness. Jakarta has faced challenges in providing open public spaces and green areas due to financial constraints, leading the government to involve the private sector. However, this approach was unprecedented in the country, and the result was yet to have proper analysis, thus making its effectiveness doubtful. Jakarta lacks specific regulations for public spaces, contributing to management confusion and failure to meet public green open space requirements set in 1965. This research fills a gap in discourse by employing an index of publicness to assess urban spaces. Methodologically, the research utilized a mixed-method approach comprising surveys and interviews with 229 participants at four case study locations: Taman Monas, Taman Menteng, Tribeca Park, and Hutan Kota by Plataran. The study found that the involvement of private sectors in the management of publicly owned open space resulted in a low-only 29%-publicness level. The study emphasizes the need for Jakarta to establish robust regulations that prioritize public access and democratic participation in the management of urban spaces. Clear guidelines are essential to mitigate the negative effects of private sector involvement, ensuring fair distribution of resources and fostering a sense of ownership and belonging among the city's diverse population.

The 18th Asian Games 2018 in Indonesia were held in the Bung Karno Sports Complex (Gelora Bung Karno/GBK), a historical site built for the 4th Asian Games 1962 when Indonesia was hosting for the first time. To prepare for the event, the game courts and landscape received massive facelifts, including the 4.5-hectare golf court that was transformed into an urban forest known as Hutan Kota Senayan (Senayan Urban Forest), later popular as Hutan Kota GBK. During the event, the space was used as a state banquet venue. Later, the government—perhaps because of the experience—decided that it was time for Jakarta to have a world-class venue and sent out requests for management proposals to various private companies.

Plataran Group, an Indonesian tourism company that owns and operates luxurious hotels, dining and private cruises, won the bid. They received management rights for a 3.2-hectare, or approximately 71%, of Hutan Kota GBK's area. News articles stated that the site will be a world-class outdoor event venues imbued with Indonesian cultures, cuisines, and craftsmanship that are open to the public. They rebranded the area as "Hutan Kota by Plataran." The management of 71% of a public space area by a private company, whose business is in the high-end tourism sector, triggerred this research because the city is already deprived of good public space. The goal stipulated in the city’s 1985 master plan and the national law of providing at least 20% of the city area as public green open space in twenty years was never met. The creation of a 4-hectare public urban forest out of a golf court was supposed to aid, but the opportunity might have been lost.

The government did attempt to make the space "public" by transforming a golf court into an urban forest. Regarding this, some discourses have also noticed the blurred boundaries between public and private spaces caused by the involvement of the private sector in the ownership of public spaces (Crawford, 2016; Schmidt, Nemeth et al., 2011; Smith and Low, 2013). Privatization was reflected in the design and management that filters visitor types, thus depriving the space of its democratic quality (Aelbrecht, 2022). Therefore, this paper analyzed Hutan Kota alongside three case studies: Taman Monas, Taman Menteng, and Tribeca Park, to figure out the publicness level of public spaces in regard to their ownership and management. This research chose the term privately owned public space (POPS) as an identifier of the research subject because the term directly indicates private sector involvement.

Several research emphasizes three reasons why POPS are naturally exclusive (Lee, 2022). First, the design of POPS such as a fortressed environment makes citizens perceive that some of them that afford to access the space (Nahar Lata, 2022; Németh, 2012). Second, the failure of the government to provide public facilities with a private sector led to the breach of agreement and make POPS be underutilized (Lee, 2022). Lastly, POPS are inaccessible due to a lack of knowledge that those places can be visited (Lee, 2022).

On the other hand, the POPS program become favorable due to a shortcut to get public space for free which government does not have to allocate its money or its land (Lee, 2022), POPS mechanism fits in to agenda in using land in urban efficiently, and POPS have great potential to be urban oases for people in densely developed areas (Koo and Lee, 2015).

This research is important and timely to evaluate the protection of the public’s right to public spaces in Jakarta. Therefore, this research addressed the following research questions:

The analysis utilizes users’ and non-users interviews method to create a cohesive understanding of the context (Németh, 2012) and grading system to evaluate the level of publicness to improve the planning, design, and management aspects of the public space (Németh and Schmidt, 2011).

The term "public space" used in this paper is limited to outdoor parks of greeneries and open plazas or similar that citizens can access. The term will be used interchangeably with "public green open space" because the latter is commonly used in Indonesian regulations and resource materials which will be elaborated in the following section.

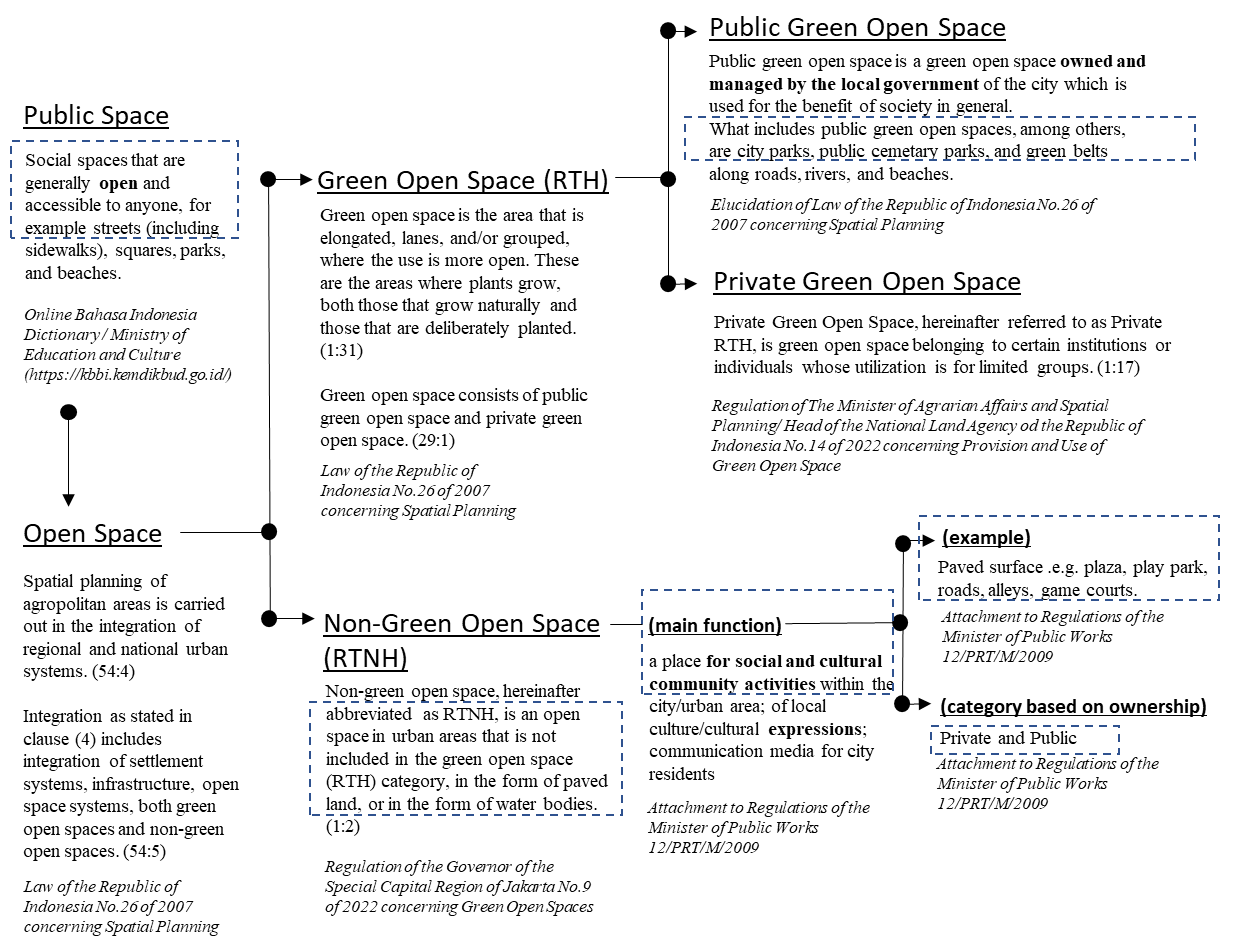

Understanding public space regulation in Jakarta starts with its development history, which began in the 1950s post-independence era with geometrically arranged offices, hotels, and commercial buildings connected by wide roads known as "arteries" (Mrázek, 2020). Development continued profitably until the 1990s, leading to a chaotic mix of luxury properties and slum areas, exacerbating issues like floods and ground depletion (Kusno, 2013). Despite sporadic planning, public spaces were often neglected, emphasizing the city's failure to grasp effective urban planning (Scruton, 1984). Figure 1 illustrates the regulation’s obscurity, which, in a nutshell, makes it confusing to distinguish between public and private spaces. The available information is also not detailed and is spread across different regulations and levels of government.

Confusion stems from ambiguous terminology, where "open space" is used interchangeably with "public space" in Indonesian regulations, further muddled by unclear definitions and scattered information across different governmental levels. The law defines "open space" primarily in terms of green areas, with public and private distinctions based on ownership (Indonesia, 2007). However, the absence of clear targets for public spaces and the emphasis on green spaces, while beneficial, have hindered progress. The law targets a minimum of 30% of a region's area as open green space, but as of 2018, Jakarta falls short, with only 5% dedicated to green open spaces, mainly parks and cemeteries. Collaborations with the private sector are proposed to meet targets, yet detailed instructions are lacking, leading to a lack of clear planning for public green spaces like Hutan Kota.

This context reveals the city's struggle to prioritize public green spaces amid competing interests. While citizens may desire public spaces, they may not find random green areas conducive to socializing, highlighting the complexities in urban planning and citizen engagement.

Ideal Type of Public SpaceIdeally, public space should be responsive, democratic, and meaningful (Madanipour, 2010). A democratic public space emphasizes the freedom to express opinions and ensures its accessibility without exception (Ho, Lai et al., 2021). Meanwhile, a meaningful public space would allow users to be strongly attached to the space, other individual users, and its environment (Carmona, 2021). The design is as essential as the provision of public spaces (Carmona, 2019). Research further argued that people would prefer well-designed public spaces that are not inclusive over inclusive government-owned public spaces (Carraz and Merry, 2022). Therefore, public space designers may first think about the utilization aspect of the area, then concretize them in the built environment. They should always acknowledge that their design will be for public use, celebrations, and ceremonies; thus, should cater to different user groups.

Aside from the usage aspect, the accessibility, connectedness, function, comfort, and aesthetical elements are equally essential to ensure comfort to users (Carmona, 2019; Spence, 2020) and encourage the public’s willingness to visit (Landman, 2016). Public transportation is more important to the accessibility and inclusivity of public spaces than it is to shopping centers and entertainment centers (Ikudayisi and Taiwo, 2022).

The current provision of public space, or the lack of it, is heavily influenced by the rapid urban development of a city. Research on Delhi stated that the city development marginalized public space as much as the poor people. Land owning competition is stirred by commercial pursuit, creating cities full of residential, hotels, commercials, etc., but the green and public spaces (Addas, 2023; Alvarez-Sousa, 2018; Mehta, 2014).

The Public Space's Degree of PublicnessThe publicness degree corresponds to the ownership, interest, and usage (Schmidt, Nemeth et al., 2011). Private sector ownership usually made the public space less public than government-owned (Wang and Chen, 2018). From the perspective of POPS, their user type is usually homogenous, thus contradicting the goal of unlimited social interactions (Lee, 2022). The users' homogeneity is apparent in the visitors' type: those from financially well-off groups. Furthermore, exclusivity encourages users to connect and interact only with fellow users from the same socio-economic background, thus lacking diversity (Madanipour, 2015).

Yet, POPS were made possible because of the incentives involved (Guo, 2017); the permission to add a certain number of square footages to the private entity’s buildable areas (Lee, 2022). The lucrative incentives urge private sectors to create 'public' spaces with questionable planning and design. Their public space later formed what was known as pseudo-public spaces. There is, however, an example of the positive impact of a POPS in Hong Kong. Even though it was a POPS, the place was able to provide a relatively free environment in which the public can meet, gather, stay, and conduct their daily social urban life (Rossini and Yiu, 2021).

The research argued that the private sector and the public should work together to ensure the publicness of the space (Leclercq, Pojani et al., 2020). This goal is achievable by developing trust, inclusivity, and transparency in the partnership. The public's participation can protect the people's rights to public spaces. Additionally, it covers a broader axiological dimension concerning a democratic society; the community's confidence in authorities (Sienkiewicz, 2020). Therefore, this research utilizes Varna index to analyze the degree of publicness from user and non-user perspectives (Varna, 2016). The addition of non-users in the analysis will enrich previous research focusing on the built environment and the user perspective (Langstraat and Van Melik, 2013).

Private Involvement in Public Space ProvisionThe government built vertical and roof gardens in South and Central Jakarta (Jakarta Provincial Government, 2019; Setiowati, Hasibuan et al., 2018) as a green initiative, yet it does not solve the issue. The government then encouraged private entities’ participation in public space provision through incentives including a 50% discount on property tax and permission to use 50% of the built space for advertisement purposes. Likewise, vacant properties that otherwise can be a public space are subject to doubled property tax according to the Governor’s Regulation Number 41 of 2019. Whether this combination of incentive-disincentive policies has led to the proliferation of pseudo-public spaces in Jakarta has remained unknown.

The number of POPSs increases over time (Lee, 2022). Hutan Kota (Urban Forest), a public space managed by Plataran Group, is an example. Plataran Group deals in luxury hospitality, with high-priced products such as a dinner for two costing up to IDR 500,000 in South Jakarta. This is equivalent to 11% of the minimum wage. The trend is similar in other spaces such as the Central Park Mall (Zuhri, 2021).

Ideally, a space design is for the targeted user (Zamanifard, Alizadeh et al., 2019). As the original target of public space is the public, it should be responsive to their needs to enter and express themselves freely and be meaningful (Carraz and Merry, 2022). Unfortunately, the policy does not include any design guidelines. Therefore, the POPSs cater to profitable users: well-educated and well-off people (Crawford, 2016; Lee, 2022; Németh, 2012). The profit-oriented management has filtered undesired visitors (Wang and Chen, 2021). The lucrative incentives, the lack of regulation, and the increases in property values lead to more establishment of inaccessible POPS. Therefore, the government’s incentive policy could not achieve its original objective.

We combined existing research to build a measurement index consisting of six dimensions and thirty-three indicators presented in Table 1. The first dimension is the publicness of the space: whether it is considered public, beneficial, designed according to what the public needs, and utilized by various groups. This subjective question was to capture the idea of a good public space as it differs amongst individuals (Varna, 2016). The second dimension is ownership and management, based on the respondents’ knowledge: whether it is owned and/or managed by the public (government) or the private. We also asked respondents which activity, commercial or non-commercial, they thought was more prominent on the site.

The third dimension is control, consisting of five indicators: CCTV, security guards, signage, physical barriers, and operating hours. Respondents shared what they thought about the presence of control. The scoring is subjective because CCTV and security guards may be beneficial when present in an adequate amount proportional to the area to give users a sense of being safe but not monitored (Whyte, 1980), or not when it is too restricting. The "physical barriers" refer to the architectural aspect that enables the user to have the sense of being in a "space" (Mehta, 2014; Scruton, 1984) instead of simply being outdoors. The "operating hour" indicator scoring is based on the preposition that a public space is safer when it is actively used (Mehta, 2014; Whyte, 1980).

The fourth dimension is design, which relates to convenience (Mehta, 2014) and how the space encourage usage (Schmidt, Nemeth et al., 2011). We asked the respondents what they thought about the quality of the waste bins and toilets on site. Benches (preferably moveable) and street food vendors are included because they attract people (Whyte, 1980). A covered shelter is included to represent the comfort aspect that Jakartans are looking for (Van Leeuwen, 2011), while a jogging track and greenery are included as they are available in all case studies. We added the maintenance level to complete this dimension. The addition of dimensions of accessibility and activity is linear with the "open" concept, which is obtained from the ease of access by all types of users, including those who are physically disabled. The question is important because the design might be encouraging user to visit yet the regulations may decrease its accessibility (Schmidt, Nemeth et al., 2011). If the place is accessible, is it fenced and heavily guarded? Does the accessibility include any artistic displays on the site? We also ask about the prices of goods, including food, sold on site to discuss economic accessibility. Meanwhile, the activity dimension is divided into four categories: communal, sports, leisure, and politics.

| Dimensions | Indicators | Scoring | Maximum score |

|---|---|---|---|

| User’s perspective on the publicness of the space | The space is public |

0 = Not applicable 1 = Somewhat applicable 2 = Very much applicable |

10 |

| The space is beneficial for the public | |||

| The space’s design adhered to what the public need | |||

| The space allows interaction between users | |||

| The space is utilized by various groups | |||

| Ownership & management | Ownership |

0 = Private sector 1 = Do not know 2 = Public sector |

6 |

| Management | |||

| Commercial vs non-commercial public activity apparent on site |

0 = mostly commercial 1 = both are apparent, in similar frequency 2 = mostly non-commercial |

||

| Control | CCTV |

0 = not available or too many 1 = a few or lacking compared to size 2 = adequate |

10 |

| Security guards | |||

| Signages |

0 = not available 1 = barely discernible 2 = adequate |

||

| Physical barriers | |||

| Operating hours |

0 = less than 6 hours 1 = 6-10 hours 2 = more than 10 hours |

||

| Design | Waste bins |

0 = not adequate 1 = somewhat adequate 2 = plenty |

20 |

| Benches / seats | |||

| Toilets | |||

| Jogging track | |||

| Covered shelters | |||

| Green area | |||

| Vegetations amount and variety | |||

| Sponsorship signage |

0 = plenty 1 = a few 2 = not available |

||

| Street food vendors |

0 = not available 1 = a few 2 = plenty |

||

| Maintenance level |

0 = lacking (broken or ditry) 1 = somewhat usable 2 = adequate |

||

| Accessibility | Walking distance to nearest residential area |

0 = far 1 = walkable distance 2 = comfortable walking distance |

12 |

| Public transport’s location from site and availability |

0 = not available 1 = adequate 2 = plenty |

||

| Spatial accessibility |

0 = not accessible 1 = somewhat accessible 2 = accessible for all user |

||

| Artistic element or objects |

0 = not available 1 = somewhat available 2 = plenty and fully accessible |

||

| Gate(s) |

0 = fully gated 1 = gated but not strictly 2 = not applicable |

||

| Average price of commecial products sold onsite |

0 = mostly expensive 1 = some are affordable 2 = mostly affordable |

||

| Use (activity) | Communal |

0 = not apparent 1 = few 2 = appear often |

8 |

| Political | |||

| Sport | |||

| Leisure | |||

| Total maximum score | 66 | ||

In the survey, we focused on the respondent’s preference for the necessities or agreeability of indicators without scrutinizing too much on the details to avoid bias. We omitted questions regarding the case study degree of publicness; the signage, physical barriers, and operating hours of the control dimension; the amount and variety of vegetation and maintenance level of the design dimension; and the walking distance, spatial accessibility, artistic elements, gate, and average price of goods sold of the accessibility dimension. We added a question regarding parking spaces to the accessibility dimension to include an option for private vehicles' users.

Case study objectThis research presents case studies on three different scenarios of public space ownership and management. The cases examined include (1) government ownership and management, (2) private sector management of government-owned public spaces, and (3) private ownership and management. Each case study focuses on the degree of publicness of the public space, analyzing it in terms of six dimensions: user, ownership and management, control, design and image, accessibility, and use of public space. The locations selected for the case studies are representative of the three types of cases. This research analyzed four case studies: Taman Monas, Taman Menteng, Tribeca Park, and Hutan Kota by Plataran.

Two parks, Taman Monas and Taman Menteng, will undergo case studies to exemplify the first type of public space. These parks are generally perceived as public spaces by the public as they are owned and managed by the government. Their primary function is to serve the public interest. Taman Monas is a 75-hectare public green open space where the Indonesian National Monument stands. Currently, Taman Monas is owned and managed by a public service body under the government of Jakarta. Aside from the monument and the museum, Taman Monas is also known for its dancing fountain show, jogging track, game courts, and sizeable green open space filled with large trees. The second case study, Taman Menteng, is a 3.9-hectare park built in 2007 by the government to replace a dilapidated colonial-era soccer stadium established in 1921. The main attractions of this park are the jogging track and sports fields, a large greenhouse, and the green space. Taman Menteng is popular among residents of the nearby Menteng residential area, which is one of the wealthiest neighborhoods in the city and whose history dates back to the colonial era. The space is owned and managed by a public service body.

For the second type of public space, a case study was carried out in the City Forest by Plataran. Hutan Kota by Plataran is a 3.2-hectare area built within the 4.5-hectare urban forest surrounding the GBK complex. The area is owned by a public service body under the Ministry of the State Secretariat and managed by a private entity, the Plataran Group. Hutan Kota by Plataran provides high-end restaurants, an outdoor event area, an amphitheater, a jogging track, a basketball court, and a playground for pets.

And for the last third type of public space, a case study was carried out in Tribeca Park. Tribeca Park is in an inner court of a shopping center in Jakarta. This space is owned by the private sector but used by the public, or what is also known as privately owned public space. Tribeca Park was designed and built as a courtyard that provides an outdoor entertainment area and jogging track surrounded by commercial establishments such as a café, restaurant, and specialty store. The amphitheater and koi pond are the main attractions of the space. Furthermore, the research will discuss further the degree of publicness in Tribeca Park as a representation of public space owned by the private sector.

Data collection methodThis research used purposive sampling method by selecting respondents who are on the site of one of the case study or have visited at least one of them. We used field observation, interview, and online survey to collect our data. The field observations and interviews with 190 respondents were conducted from October to December 2019 on weekends. Hutan Kota by Plataran had the fewest visitors because it was only opened in the second week of December 2019, when data collection began, and had to be locked down immediately because of the pandemic. Additional data was retrieved using an online survey in the second half of 2021, when the spaces are still closed to the public. We received responses from 221 individuals referred to as "users." Table 2 provides details of the respondents for both the interview and online survey data collection activities.

The online survey using scoring in the measurement index from 0 to 2. Each question refers to the focused variables of this research. The target respondents are individuals who have visited the space and engaged in activities. The questionnaire can also help identify social groups of users based on respondents' age and occupation. The respondents were screened at the beginning of the questionnaire to ensure their valid responses. To determine the scores for each dimension at each case study location, we calculate the average value of each indicator from the total number of respondents. The total indicator results are then used as the dimension value for each case study location to reflect the level of publicness based on each dimension.

|

Method : interview Total interviewee : 190 visitors |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taman Monas | Taman Menteng | Tribeca Park | Hutan Kota by Plataran | |

| Interviewees per site | 86 | 23 | 76 | 5 |

|

Method : online survey Total respondents : 221 users |

||||

| Respondents who have visited the sites | 110 | 77 | 12 | 22 |

Table 3 presents the on-site interview result, of which Taman Menteng received the highest score, 51/66 or 77%, followed by Taman Monas, Tribeca Park, and Hutan Kota by Plataran respectively. It scored the highest on all dimensions except "ownership and management" and "use," which were tied for second place with Taman Monas.

| Dimensions | Taman Monas | Taman Menteng |

Tribeca Park |

Hutan Kota by Plataran | Maximum score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of interviewees | (n=86) | (n=23) | (n=76) | (n=5) | |

| Perspective on the publicness of the space | 10 | 10 | 8 | 2 | 10 |

| Ownership and management | 6 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 6 |

| Control | 7 | 10 | 5 | 3 | 10 |

| Design | 12 | 13 | 6 | 8 | 20 |

| Accessibility | 7 | 8 | 2 | 3 | 12 |

| Use (activity) | 7 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 8 |

| Total score | 49 (74%) | 51 (77%) | 25 (38%) | 19 (29%) | 66 (100%) |

The findings from Table 1 shows a relationship between ownership and management with the perceived level of publicness of a public space. While POPS like Tribeca Park and Hutan Kota by Plataran scored 38% and 29% in terms of publicness, respectively, public spaces owned by the government scored higher at 74% for Taman Monas and 77% for Taman Menteng. However, ownership alone does not determine the publicness of a space. As seen in the case of Tribeca Park, which scored higher than Hutan Kota despite both being privately owned. It's worth noting that Hutan Kota opened during the pandemic and was restricted shortly after, which may have affected its publicness score.

Taman Menteng’s high score in the "accessibility" dimension might be due to its location near a public transportation hub (Figure 2) and nearby residential areas (Figure 3). During field observation, we found that many of the visitors are wearing casual at-home outfits and access the park by walking, which indicates the nearness to residential areas. The space also received the highest score in the "control" dimension. We counted five security guards and a few CCTVs scattered at several points. Although the amount is not plenty, our interviewees think that it is adequate. Taman Menteng also received a high score in the operating hours indicators, as it is open every day from 5:00 a.m. to 11:00 p.m. Interviewees that live nearby admitted that they often use the park at night for sports games to avoid the midday heat. Both Taman Menteng and Taman Monas received an equal score for signage and physical barriers. Taman Menteng utilized low bushes (Figure 2) and a wide, ceramic-covered platform that differentiated itself from the adjacent sidewalk (Figure 3), providing the required spatial quality. There was a line of fence but only on one side of the park, which was not considered an obstacle by the interviewees. Taman Monas is also easily identified from the surrounding area, mainly because of the landscape. Even though Taman Monas has iron fences on all sides, the interviewees think that it is not an obstacle, as the park is large enough to avoid feelings of restriction.

Taman Menteng also scored the most in the "design" dimension, mainly on the waste and hygiene facility and maintenance level, although Taman Monas gained more from the green areas and vegetation. Interviewees considered seatable areas in Taman Monas, Taman Menteng, and Tribeca Park to be equally plentiful. This is intriguing because our observations found this aspect to be severely lacking in Taman Monas, particularly because seats on these sites are permanent (Figure 4), preventing users from exercising their choice, which is preferable in public space (Whyte, 1980). Meanwhile, sittable areas in Tribeca Park are also similar; the only moveable seats are those reserved for paying customers of outdoor dining establishments (Figure 5). What helped Taman Monas gain points in this indicator is perhaps the now lifted "no stepping on the grass" regulation, as visitors are free to hold their picnic on the grass, making interviewees agree upon the adequateness of sittable areas.

Hutan Kota by Plataran received a high score in the design dimension, perhaps because the site was built with a customer-oriented mindset and thus provided a complete, well-managed, and comfortable space for their activities. It also received a higher score in green area and vegetation compared to Tribeca Park by taking advantage of being located in an urban forest and the larger area coverage. Taman Monas generally received a high score in the green area because of the lush trees, despite being packed only at the perimeter. Visitors were unable to take shelter from the sun if they were coming to the national monument and museum at the center of the park. In terms of hygiene facilities and overall management level, Taman Monas received the lowest score. We noticed that the toilets and waste bins were indeed limited and not well maintained.

The visitors’ perspective of the publicness level is interesting: that Tribeca is almost as public as Taman Monas and Taman Menteng, even though it is basically a shopping mall’s courtyard, fully owned and managed by a private company. Meanwhile, Hutan Kota by Plataran, which is located inside a large public urban forest and attached to a national-level public sports complex and owned by the public sector, falls far behind Tribeca in this dimension. Additionally, during field observation, we found that Taman Monas applied a fee for entering the park and an additional fee if the visitor wanted to enter the National Monument and museum. Even though Taman Menteng, Tribeca, and Hutan Kota by Plataran do not apply an entrance fee, only Taman Menteng can be considered non-segmented. This is because Tribeca can only be accessed through the shopping center. Some of the interviewees at Tribeca admitted that they feel bad if they don't purchase anything while they are there, be it from the surrounding restaurant or simply shopping at the mall, but they also admitted that they are not explicitly required to do so. Whereas Hutan Kota by Plataran is guarded by security personnel who, at the time we visited the site, inquired about visitors' intentions.

The only commercial area in Taman Monas is near the main gate, which consists of several restaurants and souvenir kiosks, while Taman Menteng has a food court. From the perspective of affordability of goods, our interviewees admitted that restaurants at Hutan Kota by Plataran are costly. In Tribeca, we told our interviewees to consider the price of goods sold only at places adjacent to the perimeter or that have outdoor dining areas on site, and they considered it costly as well. We could not find any street food vendors on site at any of the case study locations during our observation.

The "use" dimension result showed that all four public spaces accommodate leisure, but only Taman Monas also accommodates political activities, and only Tribeca is not used for sport. The purposive perspective (Pospěch, 2020) and the definition of "public" (Madanipour, 2010) confirm that the political activities that happened on the site made Taman Monas a more public space compared to the other case study objects. This is interesting because Taman Monas has a lower accessibility dimension score than Taman Menteng. which then prompts the question of whether the publicness relies more on freedom of access or freedom of speech. This is further analyzed using our second dataset.

Users’ agreements upon dimensions of publicnessTable 4 presented the online survey result, in which 51% of respondents preferred public ownership and private management in the case studies. The other 37% of respondents prefer full public ownership and management, and 12% prefer them to be fully by private. 51% of respondents agreed that commercial activities should be permitted on the site. This is aligned with the result of the "design" dimension, of which 74% of respondents do not mind the existence of advertising and sponsorship. The results indicate that public ownership of green public space is deemed essential, but users do not mind the involvement of the private sector either.

| Dimension | Indicator | Preferrence / Agreement | % (n=116) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ownership and management | Public ownership and management | 43 | 37 % |

| Public ownership and private management | 59 | 51 % | |

| Private ownership and management | 14 | 12 % | |

| Commercial activities to be conducted on site | 59 | 51 % | |

| Control | CCTV | 114 | 98 % |

| Security guard | 101 | 87 % | |

| Accessibility | Public transport | 116 | 100 % |

| Parking space | 114 | 98 % | |

| Design | Trash bins | 94 | 81 % |

| Toilets | 94 | 81 % | |

| Seats | 73 | 63 % | |

| Shelterred areas | 44 | 38 % | |

| Greenery | 38 | 33 % | |

| Jogging track | 5 | 4 % | |

| Street food vendors | 74 | 64 % | |

| Advertisement and sponsorship | 86 | 74 % | |

| Use (activity) | Communal | 114 | 98 % |

| Political | 9 | 7 % | |

| Sport | 115 | 99 % | |

| Leisure/Re | 113 | 97 % |

We propose a matrix in Figure 6 illustrating the user’s preference for the other dimensions by priority depending on the percentage of agreement, from the lowest average score (left) to the highest (right).

The study found that respondents were mutually agreed on the importance of accessibility above control, use, and design, respectively. In the accessibility dimension, all 116 respondents agreed that public transportation is necessary, whereas only 2 of them think that parking spaces are not. This indicates that a flexible option for access is preferable. Following "accessibility" are the "control" and "use" dimensions. 114 respondents, or 98% of the total, prefer CCTVs to be available on site, and 87% agreed upon security guards' existence. Additionally, in the use dimension, more than 97% of users agreed upon conducting communal, sporting, and leisure activities in public spaces, yet only 7% (less than 10 people) agreed upon conducting political activities.

The "design" dimension result indicates the importance of waste and hygiene facilities, a somewhat average preference for street food vendors and sittable areas, less on green space and shelter areas, and a very minimal preference for jogging tracks. The waste and hygiene facilities are prominent because the case study objects are treated as entertainment or tourism destinations. The importance of food and seats emphasizes Madanipour (2010) analysis of what makes a public space "public," as they attract more people. The interesting result is the lack of preference for greenery and shelter, which makes the thermal "comfort" aspect seem less relevant compared to "security." The mentioned findings are consistent with Rajabi and Shrifian (2022) study that stated a decrease in social traits like equality, cohesion, and security can lead to a reduction in diversity in social activities. This further explains that the "control" dimension is a more crucial user preference that affects the activities that users engage in public spaces. The results indicate that politics is considered something that confronts the sense of security, which is deemed necessary in public spaces. This is consistent with the theory that political activities, particularly those in the public sphere, are closely monitored (Pospěch, 2020), even though politics is a right and what defines the citizens as a public.

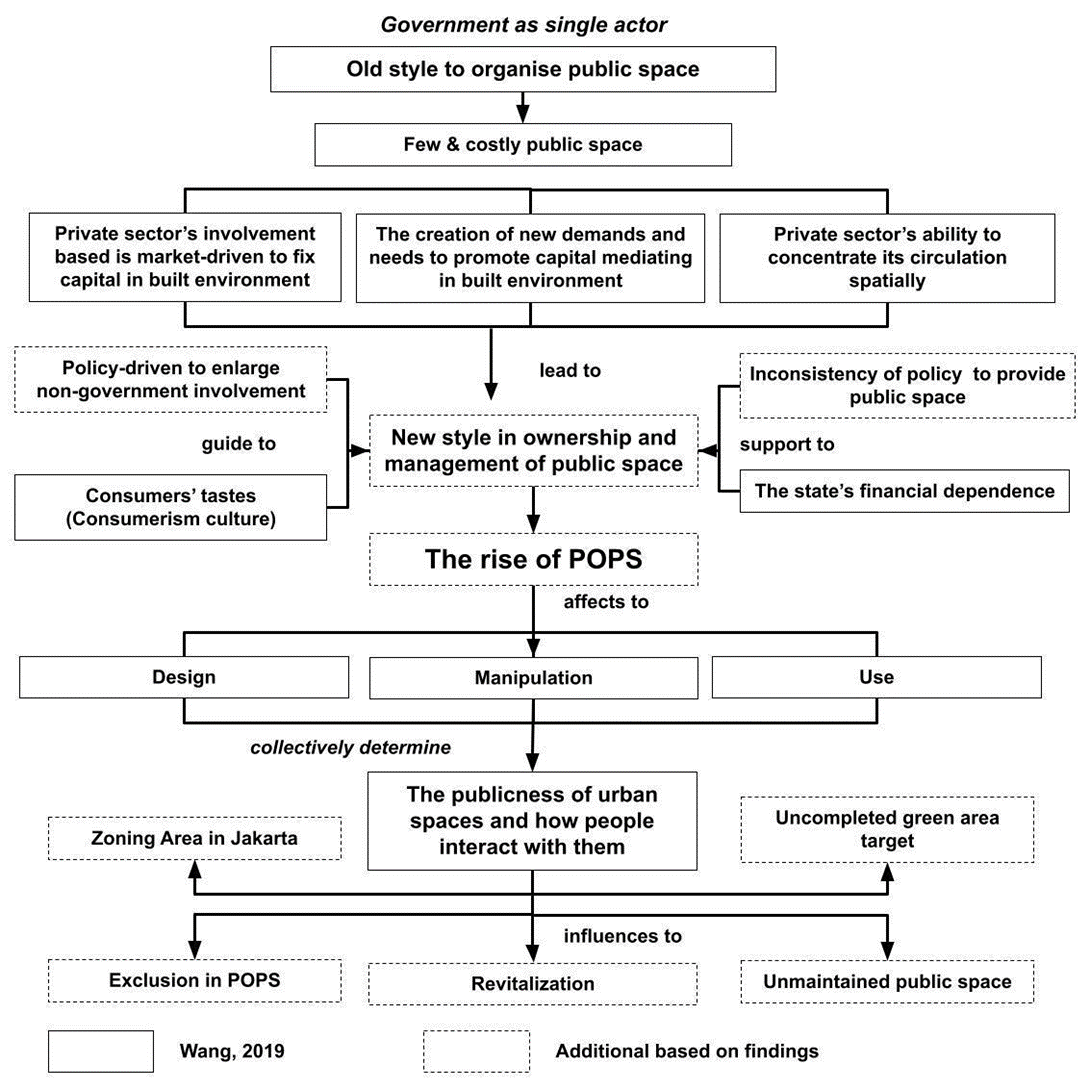

Our research analysis conforms to the notion that public space has always been privatized since its conception (Lee, 2022), though the responsible party varies by case. This research adopted Wang (2019) transdisciplinary framework for analysis. As he mentioned the evolution of public space provision led to a decrease in publicness in urban space. But his research does not provide the influence of political regime and policy’s dynamic as an essential factor to explain phenomenon more comprehensively. As underpinned in Wang (2019), this research enriches scientific discussion with the dynamic of local context in policy and the political regime when there are instrument tools in analyzing data. Based on the findings, the model is being reconstructed in Figure 7.

The adjustment of the model is based on Jakarta’s context, where the dynamics of policy and political regimes influence the rise of POPS as greater private sectors’ involvement. Greater private sectors’ involvement drives a condition in which the government is more dependent on public space projects funding Huang (2016). Numerous public spaces and green open spaces has been built or revitalized but have a consequence in reducing the level of publicness with physical symbolic such as PT Sinarmas Logo in Kalijodo Parks. The logo becomes a sign that means private sectors have a concern in public needs and to gain benefits positive image.

Additionally, most the governors only focused on providing public space to beautify the city’s image, especially in 1999, not to improve the quality of life with public space’s presence. On the other hand, commercial areas development is one of predominantly concern from now and then. The proliferation of commercial areas which are not fully as inclusive public space in decades implies that the government’s concern was not solid to develop inclusive public space for all social classes.

The mainstreaming of inclusive public space provision was seen since 2012, where the target of public space was one of each sub-district, the initiation was strongly supported by private sectors’ involvement. Nonetheless, the involvement is mostly driven by profit or as private sector capital accumulation. For developers, the image of publicness in their developed places could attract more people’s initiation to buy or consume Rajabi and Shrifian (2022).

The phenomenon is like what occurred in China, Wang and Chen (2018) discloses that in China, public space provision runs through collaboration with the private sector. The collaboration is increasing the pace in providing numerous public spaces & POPS and promoting commercial areas. At the same time, this leads society to become consumers, not citizen along with the dominance of commercial activities and greater depoliticization in the public sphere. So that there is a public space that is inclusive, exclusive, and pseudo which makes the inclusiveness of the public spaces is diverse and contextual (Wang and Chen, 2018).

(Modified from Wang (2019).

The POPS in Jakarta grew because of the incentive policy yet deprived of the function and definition of public place as indicated from the analysis result. In Jakarta’s public green open spaces that are labeled "public," the government as owner still applies an entrance fee and operating hours, thus transforming the space into a tourist destination. This indicates that POPSs in Jakarta are no longer public; they are highly controlled, panoptic, filtered, and isolated from their surroundings. They are fortressed environments with limited operating hours and filtered visitors (Carmona, 2021; Carraz and Merry, 2022; Ho, Lai et al., 2021; Madanipour, 2010). Tribeca Park, for example, is the POPS that welcomes only the visitors accessing through sister companies: the mall and the apartment complex. A non-user stated that the cause of reluctance to visit Tribeca Park was the assumed purchases visitors should make. Meanwhile, Hutan Kota GBK, which once had the potential to be a true public green open space, has made 71% of its area quasi-public by allowing entry only to those who are willing to pay for commercial transactions on site, though the entrance is still free. The Plataran Group CEO has indeed emphasized the cost of investment that was fully funded by the company and their target of having as many visitors as possible because they need that return (Maulana, 2019; Mutiah, 2019). Hutan Kota by Plataran is as, if not more, segmented as Tribeca, yet Tribeca is understandable because it is owned and managed by a private company, whereas Hutan Kota by Plataran is technically owned by the public.

The POPSs have become commercialized establishments that cater to the well-off society members whilst ignoring the others (Lee, 2022). Unfortunately, the exclusivity of users and activities displayed by the management is the antithesis of public space (Carmona, 2019; Ho, Lai et al., 2021). What we found interesting is that it is possible for users to perceive a private green open space as public because of its free access and no onsite purchase requirement policies, even though the social pressure to conduct commercial exchange also exists on site. This perception supports the preposition of consumption being attached to civilization (Ranasinghe, 2011) and who the user considers as "public." Hence, the government's provision of green open spaces that are not entirely public—whether intentionally or unintentionally—is not necessarily a fault. However, in cases like Hutan Kota by Plataran, the space of consumption is so heavily segmented that it caters to a very small consumer group.

Additionally, the respondents’ generally lukewarm responses to the privatization of public open spaces indicate that they have not moved on from the security concerns that kept Jakartans from visiting public spaces in the 1990s (Van Leeuwen, 2011). The government and private entities involved in the ownership and management of open spaces have been able to feed this concern through designs that enable formal (Huang, 2016) and orchestrated (Mitchell, 1995) interaction between users. As a result, even if a user encounters a stranger in a public green open space, that stranger will not be immediately associated with a threat. This is because the user feels like they come from the same civilized group—the group that is being catered to according to the design of the space of consumption the place has become.

The government-owned public spaces were not that good either. This research has found that these public spaces have failed in providing a meaningful, comfortable, and balanced environment (Carmona, 2019). Their amenities and features were not well-maintained and generally lacking in usability. The designs are similar between different places, exempted from the aesthetically pleasing object, and poor definition of space. The places are also unaccommodating for the vulnerable, despite this topic having been the center of discussion for some time in the city (Jakarta Provincial Government, 2019). Interviewed users agreed that the government-owned public spaces are neither safe nor relaxing. The public spaces do not have any surveillance or security system, which indicates poor control dimensions considering the constantly increasing crime rate in the city (Bagja, 2021). The situation might be related to the lack of funding allocation dedicated to this sector.

The findings of this research have significant implications for various stakeholders involved in public space management. For architects and policymakers, the developed index can serve as a vital tool for creating and refining guidelines and designs for POPS, ensuring they meet public needs effectively. The private sector must recognize the importance of maintaining genuine public access rather than prioritizing commercial interests, thus contributing to more inclusive and beneficial public spaces. The general public should be informed about their rights and obligations regarding the use of public spaces to enhance community engagement and proper usage. Moreover, the government must implement transparent and accountable monitoring systems to ensure public spaces fulfill their intended purpose, thereby enhancing the overall management and quality of public spaces in Jakarta.

This study explores the level of publicness of four open spaces in Jakarta using an index built from available research. There are several findings reflected in this research. There are several findings reflected in this research. Firstly, based on the four open spaces we use as a study case in Jakarta, we learn that the POPS in Jakarta display a pseudo-publicness quality. They are, in theory, public, yet the management prefers the public to generate income. The study found that the involvement of private sectors in the management of publicly owned open space resulted in a low-only 29%-publicness level. This first finding leads to the second: the indication of misuse of incentive policy behind the establishment of POPS because the increased number of public spaces under the POPS category does not bring the expected benefit for the people. The third finding is the urgency to strengthen the policy using strict guidelines and supervision of the creation of POPS. The monitoring is crucial for a transparent and accountable POPS. This finding suggests that public spaces should be well documented in a database system. This system can assist the government in attaining the public space provision goals and the people knowing and using public spaces as private entities in their cooperation with the government.

Ultimately, the eminent goal in creating public space should always be the public themselves. Mainly, it is the people's commitment to democratic, accessible, and free-for-all public spaces despite the ownership-management scheme behind the establishment. The index we developed for this research may benefit architects and policymakers in creating future POPS guidelines and designs. Other stakeholders, such as the private sector and the public, will then be able to access detailed information regarding their rights and obligations towards developing, managing, and monitoring public spaces, both government-owned and POPS.

However, this study has several limitations. The sample size of four open spaces may not fully represent the broader spectrum of public and private open spaces in Jakarta. Additionally, the research relies heavily on qualitative data, which, while rich in detail, may introduce subjective biases. Future studies could benefit from a larger and more diverse sample, incorporating quantitative data to provide a more comprehensive understanding of public space management. Despite these limitations, the findings provide a critical foundation for enhancing public space policies and practices in Jakarta.

Conceptualization, A.G. and W.L.L.; methodology, W.L.L., and M.P.; investigation, M.P.; resources, A.G.; data curation, M.P. L.R.; writing—original draft preparation, W.L.L., L.R.; writing—review and editing, L.R., A.G.; supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of the paper.

The authors remain responsible for the content of this paper. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the respective funding organizations.