2025 Volume 13 Issue 1 Pages 84-111

2025 Volume 13 Issue 1 Pages 84-111

Terraced houses are the most popular and dominant type of housing in Malaysia. Its design has remained unchanged despite the evolving needs of society, thus proclaiming the conventional attributes of a typical house. These attributes conform to dynamic conditions through extensive house renovations, resulting in the personalization of the home space. While a strong trajectory of spatial congruence exists, documentation and typological explorations are lacking. This paper explores a typological approach as a design framework in studying the terraced house transformation by discussing its current manipulation strategies towards hypothesizing new potentialities. Typological and spatial patterns are identified by observing transformations in two sets of case studies: ‘Actual’ projects presented in the book Terrace Transformations In The Tropics (2021) and ‘Prototype’ projects proposed in the Sime Darby Concept Home 2030 Competition. The data analysis is interpreted into a series of diagrams, using building anatomy to inform its correlation to the spatial context - establishing a design framework indicating terraced transformation. Findings suggest that the transformation of terraced types and prototypes in Malaysia is motivated by human-centric priorities based on the design framework transformation that integrates (1) agentic attributes through the notion of ‘desire-based design’ manifested in the following aspects: Desire by the Absence of Damage Needs, Home Micro-Economic, Optimizing Space/Maximizing Value, and Personalization-Customization; and (2) adaptive attributes from the eccentric value of ‘void’ driven by ‘composition-forms-programs.’ The study concludes that ‘programmatic’ adaptation is key in driving the transformation, demonstrating a better human-centric approach to exploring the capabilities of future terraced housing in Malaysia.

Terraced houses stood as a result of modernization (Gausa, 1998). In Malaysia, the terraced house strongly depicts typical 20th-century design concepts (Chee Hung and Yu Hoe, 2021) and reflects the design convention of a house. Despite the evolving needs and dynamics of society, evidence suggests that terraced house design in Malaysia has not evolved for the past six decades (Powell, 2021), which led to its monotonous character nationwide. Nevertheless, it remains the most popular and dominant type of housing in the country, deemed the most well-adapted among the locals (Rahim and Hashim, 2012). Its origin dates to pre-independence times in the form of a 19th C. Chinese timber shophouse, 17th C. Melaka shophouse, and 17th C. Dutch row houses (Saji, 2012) with 20th C. British influence (Omar, Erdayu Os' hara, Endut et al., 2017), and gradually evolved into a full-scale housing quarter typical in every city across the country. As the country developed into a modern industrialized nation, the terraced house was transformed into a commodity for rapid urbanization. Accordingly, this creates demands that eventually cause its price to skyrocket compared to any other housing type. At this point, the design of the terraced house becomes stagnant to conventions, as its evolution does not entail a change of appearance but rather the attributes it provides. By virtue of type, terraced houses reproduce themselves by repetitive attributes (Moneo, 1978) of various elements and materials, hence creating a space and a form for living. Moreover, it is believed that these attributes allow for independent transformation and future adaptations.

Despite the constant and increasing supply of terraced houses in Malaysia, the design of terraced housing provided by developers does not reflect the unique user preferences of homeowners. Thus, it often results in disruption or modification of the original layout. Although the contributing factors to this phenomenon may vary, this study focuses on the dynamic and plural needs (Leitão, 2022) of homeowners, affecting their preferences. For example, the increasing demand for better use of space and convertible multifunctional areas – a scenario propelled by the COVID-19 pandemic. In particular, the lockdowns prompted higher appreciation from homebuyers towards natural lighting and ventilation, communal spaces (Zheng, Akita et al., 2022), and parks, contributing to their health and well-being (Chung, 2021). Regarding environmental changes, it has been observed that despite providing a more supportive living environment that accommodates behavioral adaptation and cultural changes, housing modifications have adverse effects on individual families and the housing community due to the constraints of the terraced house design (Abd Manaf, Rahim et al., 2018). This rigidity in design convention seems undisputed with the unchanging design of terraced houses since they were adopted in Malaysia, even more so during its industrialization era.

Although the practice of terraced house modification is ubiquitous, there is insufficient typological exploration in manipulating existing conventions. An objective and empirical observation of terraced house transformation is key to better understanding this problem. However, there is a significant ‘dwelling-man-cell-community’ relationship in housing (Borsi, 2018). This causes the future terraced house design to be hypothetically influenced by user preference (The Star, 2022), which instills a new paradigm in its transformation process. Thus, a systematic interpretation between users’ manifestation and spatial patterns as a particular typology that could be manipulated would broaden avenues towards hypothesizing new potentialities of terraced house design. Accordingly, this allows new aspects of living to be enhanced by design.

Centered on the question of how typological manipulation transforms the existing convention of terraced house types and prototypes, this study aims to establish a typological design framework as a manipulation strategy for terraced house transformation in Malaysia. It highlights three main objectives in relation to the issues raised earlier: 1) to understand the nature of terraced house design in Malaysia and 2) to analyze typological patterns in terraced houses through the manipulation of design attributes based on two different case studies. This includes (1) ‘Actual’ projects documented in the book Terrace Transformations In The Tropics (2021) by Robert Powell and (2) the development of ‘Prototype’ projects proposed in the Sime Darby Concept Home 2030 Competition; and 3) interpret a new emerging transformational direction of the terraced house in Malaysia based on its typological pattern.

Terraced house design in Malaysia was adopted from the British scheme (Hashim, Rahim et al., 2006; Omar, Erdayu Os' hara, Endut et al., 2017), evident in its genealogy (Ioannidis, 2005). Known as “row house” in some countries, the term “terraced house” was originally used to highlight the appeal of simplicity and standardization that exists in uniform fronts and heights as being more stylish than a “row,” and the plan of each floor was always the same. Such standardization was important as a means of regulation, leading to the commencement of mass production of row houses. However, standardization seized after 1980, resulting in variants of terraced houses rather than creating a new prototype (Ioannidis, 2005). In Malaysia, the Uniform Building by-laws 1984 defines terraced houses as “any residential building designed as a single dwelling unit and forming part of a row or terrace of not less than three such residential buildings” (Uniform Building By-Laws (UBBL) 1984, 2022). The modern terrace housing units are densely located in a mirror-image arrangement with defined boundaries (Hashim and Rahim, 2008). In general, the terraced house is relatively narrow and deep, with fenestration at the front and back (Goody, Chandler et al., 2010). Inside, the interconnected living-kitchen-dining structure signifies a less hierarchical intensity, in which privacy is more flexible and manageable (Hanson, 2003; Ioannidis, 2005). Such spatial structure is evident in the Malaysian terraced house through its symmetrical order, albeit with less privacy (Omar, Erdayu Os’hara, Endut et al., 2012a).

To understand the nature of terraced house design in Malaysia, it is pertinent to note that its stagnancy reflects the country’s development principles, suggesting significant economic repercussions. The terraced house development demonstrates efficient land use and an economical road layout that enhances the number of units per hectare. Its standardized, repetitive layout presumably helps to articulate good lighting, ventilation, sanitation, and firebreaks (Powell, 2021; Saji, 2012). The layout stands within the plot area of 20 ft in width to 60 to 70 ft in length with a built-up area of 1,300 sqft to 1,800 sqft. Consequently, it typically features an attached living, dining, and kitchen area with a minimum of three bedrooms positioned on the ground floor (for a single-story unit) or on the first floor next to a family area (for a double-story unit). It is also flanked by a front porch leading to the entrance and a backyard next to the kitchen (Omar, Erdayu Os' hara, Endut et al., 2017)(Figure 1). These conventions, however, have inbuilt problems rooted in environmental and spatial aspects. The narrow and deep layout, which barely accommodates two small façades with minimal fenestration, had prevented most of the natural light and ventilation into its middle layer. This reduces thermal comfort and escalates dissatisfaction (Chee Hung and Yu Hoe, 2021; Liyana, Abd Razak et al., 2015; Powell, 2021; Toe and Kubota, 2015; Zaki, Nawawi et al., 2012). In response, improvements performed spontaneously indicate a tremendous change in its layout. This is mainly by applying passive design strategies to achieve better energy consumption (Powell, 2021; Zaki, Nawawi et al., 2012), retrofitting methods to control temperature (Tuck, Zaki et al., 2020), sculpted air-well for stack effect (Leng, Hoh Teck Ling et al., 2021; Leng, Majid et al., 2019), or strategic building orientation (Al-Obaidi and Woods, 2006).

In addition to the environmental critiques, the terraced house layout is experiencing negligence towards local culture and household change (Omar, Erdayu Os' hara, Endut et al., 2017; Saji, 2012; Utaberta, Spalie et al., 2011). Its major dilemma lies in its tendency towards having a smaller room for specific functions, obscuring the dynamic quality of the open plan (Chee Hung and Yu Hoe, 2021). As terraced units with bigger room sizes and higher room numbers create better price index and long-term demand (Lim, Burhan et al., 2021), the typical layout with smaller dimensions experience major post-occupancy changes due to misfitted functions and household activities. Note that the backyard, kitchen, study, and family hall are commonly modified through renovation (Bakar, Malek et al., 2016; Jusan and Sulaiman, 2005; Mohit and Adel Mahfoud, 2015). Indeed, terraced house renovation is pervasive to the extent that it has been instated in Malaysian culture (Saji, 2012). This phenomenon suggests an extreme failure of the existing terraced house design to fulfill the expectations of users of different backgrounds (Jusan and Sulaiman, 2005).

Lifestyle, Personalization, and Typical PerceptionTerraced houses offer a lifestyle that cannot be enjoyed in other types of residential developments (Powell, 2021). It is like an urban village where amenities are accessible by walking; experiencing an alley of immediate neighbors engaging in casual meetings and conversations establishes a certain ‘behavior setting.’ Owning their land for self-benefit and leisure also profoundly expresses personal hobbies and interests. This uniqueness undoubtedly catalyzes potential desires that strengthen individual personalities, reinforcing the inclination towards ‘personalization’ over the standardized pattern of terraced houses. Theoretically, personalization helps to signify personal identity, regulate social interaction, and mark territories, which specifically induce personal control over one’s environment (Omar, Erdayu Os’hara, Endut et al., 2012b).

It is executed in various ways – from simple decorations to the modification of semi-fixed or loose fittings into the modification of structural or fixed elements. In terraced houses, structural modification is further classified by six distinct operational modes, including extension, addition, reduction, division, removal, and relocation (Mohit and Adel Mahfoud, 2015; Omar, Erdayu Os’hara, Endut et al., 2012b). This profoundly explains the nature of renovation culture for Malaysian terraced houses in two scenarios – (1) The renovation culture is related to structural modification where it requires major constructional work regulated by the municipality and executed by builders with none to minimal intervention by professional designers (Jusan and Sulaiman, 2005; Omar, Erdayu Os’hara, Endut et al., 2012a; Sabri, Ujang et al., 2017; Sazally, Omar et al., 2012); (2) The renovation culture demonstrates an inclination towards the ‘extension’ of and ‘addition’ to existing configuration with the main objective of enlarging the existing spaces and makes use of the setback (Saji, 2012; Sazally, Omar et al., 2012). This indicates a desire to maximize the built-up area to suit occupants’ lifestyles. Both scenarios bring about the idea of ‘typicality’ – a typical template from a typical mindset for typical needs – which emerges from the supply and regulatory constraints that form users’ fixed perceptions (Baldwin, 2008). While the first scenario propagated user agency in manipulating the developer’s ready-made and presumed templates, the second scenario indicates a common insight into users’ infatuation with largeness that could presumably change a lifestyle. Consequently, this leaves no tolerance for discovering other design capabilities.

Conceptualizing A Desire-Based ApproachDesire, as opposed to basic needs, triggers transformational change, facilitating the emergence of new possibilities and the realization of human beings. (Leitão, 2022) highlighted the idea of agentic desire as a tool for creative impulses and exploratively more open-ended towards defining ‘capabilities.’ In mass housing, desires are mainly conceptualized by the theme of its existence, which somehow goes back to its theory. Ruonavaara (2018) argued that theorizing ‘about housing’ and ‘from housing’ is the way forward in conceptualizing the housing phenomenon as opposed to the theory ‘of housing.’ Such a proposition is misleading, as architecture itself is a theory ‘of’ housing that could be integrated into both ‘about’ and ‘from’ housing. However, as it is mainly rooted in social theory, conceptualizing ‘housing’ still asserts the process of re-description (relating to conceptual schematic design), explanation (responds to the query of ‘why’ and ‘how’), and interpretation (propagates ideas about meaning) that interrelates between individual and collective consumption. Biln (1995), Gorny (2018), and Nuijsink (2021) have conceptualized desire into narrative, elements, proximity, and collectivity. This could be more discursive when interpreted as architectural vocabulary that may address the agentic housing concept more thoroughly as a self-regulating principle. Although these terms embed normative assumptions, they take enduring tensions between housing and architecture that reveal their power to ‘mutate in motion’ and are often potent even if poorly defined (Vais, 2021).

Agentic FormalityCrafting desires through architecture requires a conversion of its richness – the depth structure, into complexity – formal manipulation of type (Carl, 2011). This kind of complexity allows the ‘type’ – which is described by a group of objects characterized by a similar formal structure (Moneo, 1978) to be recognized in a single horizon of representation such as code, axiomatic geometry, and logic (Carl, 2011) enclosed within the framework of typological study. In a subtle relation to housing, one could explain that desire represents this richness, manifesting in the complexity of its form, including structural, spatial, and systemic framework (Borsi, 2018; Carl, 2011; Chi, 2021; Gausa, 1998; Gorny, 2018; Moneo, 1978). Note that this set of complexity resembles the housing typology through the fragmentation between elemental composition established by traditional discipline and form-space by modern discourse (Moneo, 1978). In fact, this effort nurtured a dynamic context that allows housing agency to occur (Gausa, 1998). On the other hand, Chi (2021) investigated this phenomenon through the case of ‘incremental housing.’ This type of house acts as an artifact of interpretation where adaptability and growth are used to support livability. Meanwhile, tactical design in a polyvalence form, a term coined by Herman Hertzberger, referring to a form that can be put to different uses without undergoing self-changes to optimized solutions within minimal flexibility – creates agency beyond aesthetic appearance and potentially incites users to be more attentive to space. This inviting form is manipulated in two related components of (1) structural and constructional framework consisting of building enclosure, structure, and building system, and (2) spatial matrix of specific dimensional module and grid. However, as much as formality exists, incremental housing demonstrates unique characters based on its program.

Program as Social ConstructIn type and typological studies, it is understood that composition acts as a tool to articulate forms into programs, which is based on functions and usage, relatively described as ‘genre’ by Durand (Moneo, 1978). This occurrence conveys a pragmatic perspective that a type is a kind of actor that affects everyday life situations (Kärrholm, 2013). It has the power to turn a certain space into a socio-material actor with a certain effect that describes a territorial sort (Brighenti, 2010). In this case, the type must not be defined as a standard set of entities but perceived as a more fluid assemblage, provided the forming entities share family resemblance (Kärrholm, 2020; Mol and Law, 1994). Correspondingly, Moneo (1978) depicted this condition as a subtraction of singularity and isolated concept of type into a chain of dynamic events (Kärrholm, 2016; Koch, 2014). Hence, the program (Gausa, 1998) is enhanced by the dynamic guidelines of sequence and web, complex formation of outbreaks and maculae, and void manipulation within the fields and ground. Jones (2016) highlighted that this arrangement is somehow connected to a set of habits, beliefs, and expectations, establishing a ritual from the use-meaning associated with repetitive activities. This setting, nevertheless, if rendered through an architectural plan and section, will display the building’s anatomy, which, in this case, enables those familiar with the conventions to assemble it in their imagination. As such, the correspondence between information about buildings and information regarding rituals leads to the relationship between buildings and their programs, assuming the program is the building’s social construct.

In terms of forming the visual representation, it is learned from Koolhaas’s analogy of the domesticity of prison to a culture of congestion prompted by Manhattan skyscrapers. This is where the resulting dichotomy led him to configure society as a plastic entity susceptible to multiple diagrams and possibilities for arrangement. This analogy helps define the prison as a social condenser, allowing sectional programs to exist in horizontal bands (Martinez-Millana and Cánovas Alcaraz, 2022) – an approach adopted in this study. In the context of terraced housing, Powell (2021) outlined an emerging new social content that is currently transforming its typological morphology. These situations involve adaptation to ‘Working from Home’ (WFH), a shift towards small family living, a responsive ideology to an open living environment, and a longing for nostalgic living in a ‘kampung’ environment. It also centers on robust experimentation with an eclectic prompt that seems to create a better personalization of standardized terraced patterns.

Implementing a qualitative approach, this exploratory research mainly uses the desk review method on case studies, which are then represented in a series of architectural diagrams of spatial patterns. In terms of sampling, the study focuses on the intermediate two-story terraced house with dimensions ranging from 20 ft to 29 ft in breadth by 60 ft to 120 ft in length, representing the most common design convention of terraced houses in Malaysia. Consequently, this study suggests that this unit type is quickly falling into a state of saturated personalization compared to corner or end lot terraced units. The parameter represents a particular demographic since most households are of similar income range and family structure and are hypothetically more inclined towards having an enriched lifestyle. This approach corresponds to the Research Questions and Objectives in several stages:- Stage 1: Case Study Selection – In understanding the nature of terraced houses in Malaysia. Each set of case studies comprises selected projects distinguished by key characteristics, contexts, and concepts of terraced houses in Malaysia. This study explores its transformation in two (2) sets of case studies’ spatial patterns emerging in the spatial transformation of actual built projects and conceptual prototypes. The case studies are analyzed in the following groupings: -

A. Case Study A: Terrace Transformations In The Tropics (Powell, 2021) (Nomenclature: “House (Name)”; due to their nature of being actual buildings, as named in the source literature). Discussion: Existing site and spatial usage contexts provide a (limited) platform for design exploration in creating added value. As a result, 20 selected contemporary mid-terraced house projects are presented and analyzed for their design attributes.

B. Case Study B: Sime Darby Concept Home 2030 Competition (Darby, 2021) (Nomenclature: “Prototype (n)”; due to their nature as design concepts). Discussion: A provocation of design norms based on shifting desires and lifestyles of the future leads to a multiplicity (limitless) of design exploration and possibilities. Ten shortlisted schemes, as selected by the jury, are presented and analyzed for their design attributes.

Stage 2: Desk Review – In defining terraced house transformation in reflection of its design conventions. Instrument: Observation via document analysis (books and competition website) and video. Using ATLAS.ti 23 software, the data from case study A are deduced into a series of transformational typologies (Table 1), and case study B is coded into keywords related to the typological issues, exploration, and innovations aspects (Table 2). Both cases are represented through architectural diagrams and consolidated into descriptive and comparative tables and matrices as a form of empirical analysis.

Stage 3: Thematic Analysis – In establishing a correlative interpretation related to the design strategy of two contrasting contexts – “Actual” and “Prototype” projects. The existing types depicted through the book Terrace Transformations In The Tropics (2021)(Powell, 2021) demonstrate how the transformation was interpreted by optimizing its limitational elements and parameters that resembled the typical terraced housing design discussed in the literature. In contrast, the prototypes help to expand the significant changes that are desired in future terraced house designs. Note that networks are established in ATLAS.ti 23 software with architectural diagrammatic matrices allows for high accuracy and efficient analysis of data to strengthen theme exploration. Hence, it builds an analytical interest (Zairul, Azli et al., 2023) related to this research.

The analysis is characterized by the two sets of case studies – ‘Actual’ and ‘Prototype’ projects. It presents the extent of transformation that may be imposed on terraced house design from which the typological pattern through manipulation of design attributes can be identified and analyzed, thus fulfilling the second research objective.

In this context, the actual projects result from inherent responses to existing contexts that dictate the environmental conditions. In contrast, the prototypes are devised free from the physical and real-time constraints of reality. They are conceptual representations of design attributes that are interpreted into the typology of a terraced house.

Case Study A: Existing Terrace Transformation – ‘Actual Project’This research posits that the ‘existing’ context would better demonstrate the transformational evidence related to specific user preferences. The literature review delimits our analysis to a selection of 20 mid-terraced house units presented by Powell (2021) that display a distinguished typological order justified by their spatial organization and built-up area. It is also argued that these cases resemble the actual ‘existing’ context of transformational variance manifested by physical changes and subjective experience of the homeowners.

Typological PatternTable 1 (in the Appendix) presents the suggested horizontal planar pattern involving three longitudinal divisions of circulation, function, and services zones in a terrace unit. In addition, the traverse lines indicate frontal, middle, and rear zones, which are specified in numerical order of 1, 2, and 3, respectively. Note that the lines (longitudinal and traverse) are flexible and could be manipulated based on the built-up area and internal structure of the samples.

However, it is more fascinating to note the curiosity that occurs between the lines that are afforded by an important spatial device - the void (Figure 2). This juxtaposition leaves the void in a supreme manner, as it oscillates the spaces to be more dynamic beyond its common function of providing upright access (by means of staircases), services, light, and ventilation. In this typological analysis, the void is determined to be advocating new programs within the existing living conditions (Figure 3). One may find a new social space, a working nook, an adventurous entrance, or a biophilic kitchen all integrated by the void up to any intended level of a house. In fact, the existence of a void allows one to swap its common floor to the upper level to gain better privacy while being able to monitor the ground floor. This phenomenon offers an added value to proximate vertical spaces, provided that the original pattern (layout) is well connected to its void. Indeed, one could agree that as the line performs horizontally, the void completes the pattern vertically.

Void: Types and ProgramsIt is established that the variety of sizes influences the transformation of spatial characters and potential programs created by a particular void. Through a typological matrix (Figure 2 and Figure 3), in ascending order of size, the 20 samples are deduced into five types of void configurations, whereby in each specific group, the range could be demonstrated by one to seven variants of the program. The cross-relations between the programs occur to signify their transcending ability in every pattern discussed earlier. In summary, through the varying orders, this analysis observed 12 kinds of void programs and manners established in a terraced house, which have been classified as Circular (A1), Traverse (B2), Borrowed (B3), Threshold (B4), Hiatus (C1), Paradox (C2), Back-End (C3), Timed-Out (C4), Spatial Effect (C5 Segments), Annex (D2), Imitation (D6) and Flexi (E3).

Type A: CompactThe A-type transformation indicates a ‘Compact’ approach (Figure 2, Figure 3), H19: Twin House). It is characterized by a tripartite section of longitudinal and traverse lines with a central void as a catalyst. Analysis reveals that it is applicable to a plot of 10 ft to 20 ft in width and 60 ft in length, whereby the void acts as a pivoting spine that connects all the spaces into one without any permanent barrier. Note that 10 ft is considered the smallest width that a terrace unit could be reduced which would still render efficient. The void is made central to accommodate circulation at both sides, promoting privacy without losing contact from any level. In this mode, new programs are constructed in a circular configuration corresponding to multi-tiered leveling, up to three stories or higher.

The B-type transformation represents the ‘Minimal’ approach (Figure 2, Figure 3 – H16: Slims House) for modification of a common-size terraced house, which ranges between 20 ft to 22 ft in width and 60 ft to 70 ft in length. In this case, the term ‘minimal’ implies two situations: a minor intervention or an inherent appreciation of the existing setting. The B1 segment (the smallest plot in B type) indicates the latter, in which most of the mid-terraced house is structured. By having to only double the longitudinal and tripartite traverse section, the existing void is celebrated as-is without any modification due to its resemblance to a courtyard in colonial shophouses. In this study, it is discovered that the void is used in its original function by allowing light penetration to internal spaces.

However, within the same plot size, such sentimental value has been waived to maximize floor area. This situation is illustrated in the B2 segments (Figure 2, Figure 3 – H18: Senangin House), where the void is the circulation or vice versa. In this case, a specially modified staircase is constructed in the form of perforated metal to permit breeze and lights to preserve the traditional void. As it applies on one side, the middle aisle of the tripartite structures acts as the principal circulation, allowing new programs along the traverse line, where the rest of the spaces occupy the front and rear aisle. B3 and B4 segments demonstrate how transformation takes place at both the front and rear aisles due to the absence of the middle structure. In the case of the B3 segment (Figure 2 and Figure 3 – H17: Kinrara House), the void plays an important role in creating a borrowed program of inside-out or top-down spaces. Meanwhile, the B4 segment (Figure 2 and Figure 3– H15: Sea Park House) demonstrates how the void acts as a barrier to semi-public or semi-private spaces, separating the entrance into multiple transitions. Here, new programs are exploited as thresholds and are injected within the barriers.

Type C: MultiplyType C enhances multiple living programs in one space, hence the ‘Multiply’ approach (Figure 2). Amongst all seven variants, Type C is found to be dominating the transformations recorded by Powell (2021). Thus, it suggests itself as the preferred framework used by designers to enhance terrace living. However, the unit size is uncommon and slightly bigger, within the range of 22 ft – 24 ft width and 75 ft – 85 ft length.

The C1 segment (Figure 2 and Figure 3– H9: Riuh House) is the only framework that relies on just a traverse section, in which the void is arranged along a traverse band. In this analysis, a band void can create multiple pauses in an open plan design, creating a sort of hiatus program in between. In the C2 segment (Figure 2, Figure 3 – H4: Louvres House; H8: Sleeper House), the voids combined multiple functions in various possible manners. These combinations result in a paradox program, hence redefining the functions beyond the routine. Should this notion be placed at the rear aisle as illustrated in the C3 segment (Figure 2 and Figure 3– H5: Planter Box House), the paradox programs could be further explored as a back-end program, hence redefining the context of service zone and rear end shared area. A similar context with added value is applied on the frontal aisle as displayed in the C4 segments (Figure 2 and Figure 3– H7: Concrete Jungle House), whereby the void (considering all four sides) is functional as a timed-out program for the family.

In addition to spatial program enhancement, a void could also be multiplied to achieve unique spatial effect programs. This scenario is further developed in the C5, C5 (1), and C5 (2) segments (Figure 2 and Figure 3 – H10: Desa Lightwell House, H12: NJ House, H3: Itkka House). In the case of C5, the voids are progressively changing the spatial context. From a formal welcoming void, it gradually turns into a semi-private zone and finally resorted itself into a forbidden backyard area. Clearly, the narrative lies in its alignment. Although there is a disruption - in the case of C5 (1) – the narration continues, and it changes immensely should the void become a single continuous ‘T’ strip as demonstrated in C5 (2) segments. One may find that this condition leads to a ‘stage effect,’ where an inversion of active and passive domains occurs. Consequently, the C5 (2) confirms that the active common area of living and dining is being switched to the upper level (the stage) to optimize potential space within the roof truss and the lights. Interestingly, this phenomenon also occurs in C5, which suggests that continuation could also happen visually.

Type D: ExtendedAs the size expands, spaces tend to scale in something beyond the domestic realm, expanding into two or more independent programs within the living cell. Integration, as propagated by Types A, B, and C, is being extended and classified based on a key program that requires a proper division to be functional. Type D executes this operation by introducing a void with an ‘extended’ approach. Note that the term ‘extended’ is an anomaly, as it demonstrates dual characters of integration and division. In the D2 segment (Figure 2, Figure 3– H20: Wonky Woo House), the void acts by the integration of an ‘annex program.’ This extension relies on a specific function of adjacency, in this case, with the kitchen. As the kitchen is built into the zoning, the D2 uses the most passive zone (storage area) to complete its void, which could integrate two major programs of living and working since both spaces require storage. However, for the D6 segment (Figure 2 and Figure 3– H1: House 8), the void is made into a separator through an ‘imitation program.’ In this case, the concept of a private living space is extended collectively as an open amphitheater, which separates the living and working spheres, knowing that both require a lounging space for leisure. Intriguingly, this void also causes an extraordinary effect by applying a continuous attribute, as displayed in C5 segments, encapsulating the living zone in its own private quarters, away from the working domain.

Type E: EngagedConsisting of multiple voids, Type E (Figure 2 and Figure 3– H2: W39 House) allows for a holistic engagement between voids and all the living spaces, representing an application of all void programs from Types A to D. One corresponding element that helps to materialize this concept is the flexibility of its layout pattern whereby all the services or fixated elements are organized in one longitudinal aisle. This leaves a huge flexible space, hence the ‘flexi program’ to be manipulated.

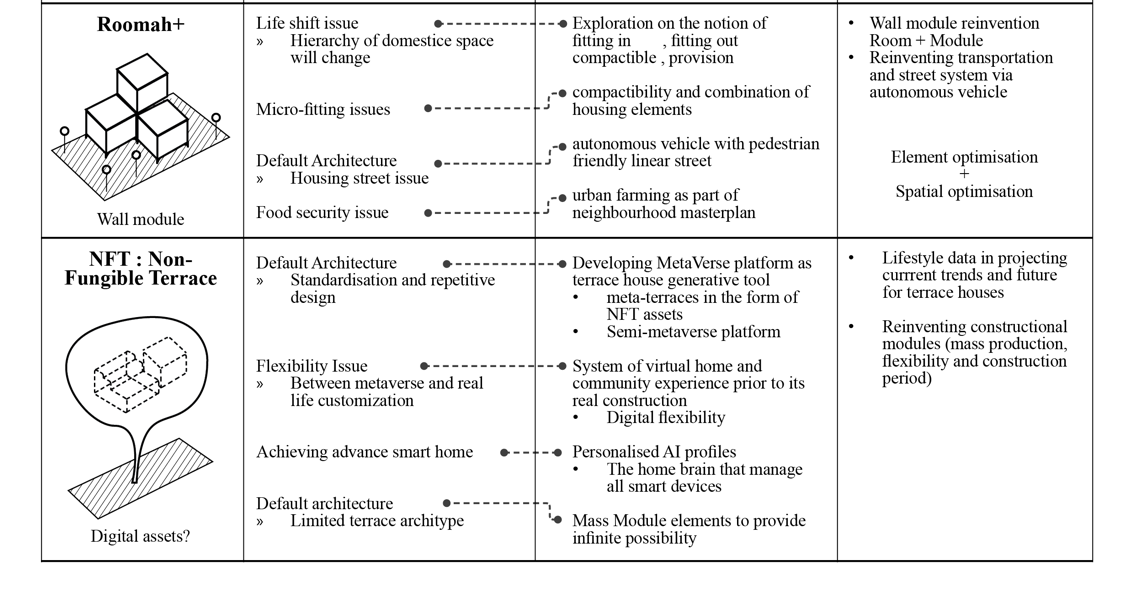

Case Study B: Future Patterns of Malaysian Terraced House – ‘Prototype Project’The Sime Darby Concept Home 2030 Competition aims to challenge the typical terraced housing design through disruptive (Darby, 2021) concepts of technology, innovation, and sustainability. It envisions a future-ready terraced house that is intelligent and able to adapt to ever-changing lifestyle trends. The ‘disruptive concept’ (Darby, 2021) is based on the four pillars of reshaping future living: (1) Sustainable solution; (2) Modular, Expandable, and Customizable; (3) Modern Methods of Construction; and (4) Tech Infused – A Home Brain; conforming an inclination towards technology-based approaches. The schemes demonstrate a more coherent objective than being technologically autonomous, which in certain aspects correspond to one another beyond the outlined criteria. This correlation offers an interesting novelty in the discourse on terrace housing while challenging the conventional terraced house design that has gone stiff and soulless. Consequently, the home is driven into a human-centric living cell where all schemes are personalized with a wide range of customization technologies that allow for better spatial optimization, hence the added ‘spatial program’ beyond the typical conventions of a home (Table 2 - in Appendix).

Figure 4 portrays the thematic design framework of future terraced housing in Malaysia as deduced from this competition. Through the content analysis method, this paper highlights four (4) main attributes of spatial pattern evolution and their consequences and contributions: 1) Models of desire, 2) Home microeconomics, 3) Personalization-customization, and 4) Spatial optimization. Figure 5 demonstrates the thematic context and its transformation into a typical 20 ft x 70 ft plot of a terrace unit. Note that the abstraction of the original scheme into a typical context is a comparative strategy by means of form limitation. This renders the transformational elements into a mass context, hence bridging the gap between a conceptual and an actual rendition.

This study attempts to question the aspirations behind the competition schemes, which advocate immense possibilities of desire beyond the needs. It is suggested that ‘desire’ is made by the ‘absence’ of damage needs, which acknowledges abnormality and forces a new lifestyle to follow suit.

As illustrated in Figure 5, Prototype 1 removes the ground platform due to climatic reasons, thus forcing a house and its living program to stay elevated. Meanwhile, Prototype 2 denies excessive use of the area due to affordability factors, optimizing a small plot of living space. Prototype 3 rejects internal barriers by having a continuous spatial flow, and Prototype 4 discards its spatial attachment by making a universal module. On the other hand, Prototype 5 (the winning scheme) detests physical attributes to allow for virtual flexibility. Prototype 6 explores the notion of multiple ownerships rather than singularity. Prototype 7 promotes shared living as opposed to individuality. Prototype 8 rejects uniformity to allow for variety. Prototype 9 redefines its passive rear façade into a double frontage, and finally, Prototype 10 redefines its sidewall for better breeze and sunlight penetration. These multiple contexts and scenarios manifesting the ‘absence’ are further described in diagrammatic sectional drawings, illustrating the building’s anatomy.

Home Microeconomic ProgramFigure 4 and Figure 5 illustrate our observation of four new programs that propagate microeconomic benefits to households. In doing so, certain spaces of the terraced house are redefined. ‘Resource Sharing Program’ in Prototypes 6, 7, and 9 enhances the idea of generating resources in a living context. It promotes self-sustaining communities by providing shared boundaries or spaces around the five elevations of a terraced house. Consequently, it allows for food production, promotes a bartering system, and shares rechargeable energy for the community.

The ‘Communal Program’ stimulates a strong community linkage within the territory of a terraced house as opposed to a conventional congregation area, implemented by a radical concept of permeable ground level, as demonstrated in Prototype 1. Should the plot be too profound, the linkage could be realized through a double-frontage concept (Prototype 9), which in return would benefit homeowners by the invention of a ‘borrowed space’ as demonstrated in Prototype 10.

The borrowed space is an autonomous space. It functions as a commodity within the realm of a terraced house, suggesting multiple conventions of a ‘Home Ownership Program.’ This could be further enhanced using modules as illustrated in the micro unit of Prototype 2 and the room module unit in Prototype 4. For Prototype 6, the proposed system becomes more commercialized by the idea of ‘Rent-Out Module Space’ that allows for separate access and purpose altogether. In Prototype 8, the diversion is based on statutory requirements of strata and non-strata development.

Limited experience and flexibility within a terraced house have shifted the paradigm into a ‘Virtual Home Program.’ Rather than merely being a digitalized scheme, it allows the user to experience the space and its context virtually, suggesting a parallel universe to be explored. Prototype 3 demonstrates the flexibility of generative design that can personalize and customize its spaces according to the user preference prior to physical construction. This combination is further elaborated in Prototype 5, as it develops its own absolute meta-system with a digital community, land, and financial asset that leads to a smooth transition of owning a home.

Optimizing Space, Maximizing ValueIn Malaysia, the expansion of internal spaces such as the kitchen and bedroom are commonplace, increasing the total built-up area by 26% from the maximum of 1,800 sqft. Such tendency signifies the interpretation of comfort into large physical size (through maximization) rather than in the space’s intrinsic value (through the act of optimization).

On the contrary, analysis of the competition reveals the opposite: the quality of space is made to be optimized rather than maximized, emphasizing its value rather than its size, disputing the status quo.

Figure 5 demonstrates how optimization occurs in each type of home microeconomics. It is interesting to note that optimization is crucially present through the concept of micro-living, as displayed in Prototype 2, or modular space, as in Prototypes 4 and 6. In this notion, users are encouraged to downsize their lifestyle, including the spaces that come with it. This situation has spurred the value of sharing (as in Prototype 7), as most of our domestic routine is substituted by the emergence of collective space and technologies.

Personalization for and Customization by the UserThe finalist schemes suggest solutions through constructional flexibility with the integration of the Internet of Things (IoT). The human-centric technologies signify the need for automated personalization, hence justifying the disparity between personalization and customization. At this point, it is essential to note that the user initiates customization, while personalization is performed by developers for the user. Moreover, acknowledging this fact reveals that the current terraced house lacks personalization, limiting customization efforts by the users or vice versa. Figure 4 and Figure 5, as well as Table 2, illustrate this phenomenon. In detail, the finalist schemes outlined three concepts of the personalization-customization dynamic: 1) ‘open plan customization,’ 2) ‘module customization,’ and 3) digitalized data-based customization.

The first concept deals with the idea of ‘open plan customization,’ where a system of permeable enclosures determines the hierarchy of space. The user could generate this through flexible contexts such as the landscape setting in Prototype 1, micro setting in Prototype 2, juxtaposed setting in Prototype 8, and hybrid setting in Prototype 10. Note that the open plan personalization is manifested by the adaptable patterns that grow concurrently with spatial customization.

The second concept relies on the idea of ‘module customization,’ where a module is dissected into customizable elements that react to the manipulation by the users. Once assembled, the module and its realm act as personalized objects that can cater to any configuration of customized patterns. For example, in Prototype 4, the wall element is utilized to form a module. Meanwhile, Prototype 7 explores the shared elements that create its envelope, and Prototype 9 exploits its expandable elements that extend into the urban realm.

The third concept could be considered a game changer - architectural personalization has been digitalized into a data set based on customization preference. Users could actively customize their terrace unit through a personalized digital application where the data would be accumulated, processed, and later generated into a physical module installed on-site. This idea is well defined by Prototypes 3, 5 and 6. However, in Prototype 5, customization is made entirely virtual, where the users are given an opportunity to experience the designed context as a representation of living.

In understanding the nature of terraced house design, as stated in the first objective of this study, it became apparent that the transformational process for a mid-terraced house is related to an interior engagement where it lacks the possibility to enter into conflict with other existing positions (Geiser, 2016). This is particularly true with the exterior elements, which are limited to the front and rear façade (Omar, Erdayu Os' hara, Endut et al., 2017). At a closer look, each case represents a unison of interior modification patterns driven by the structure and spatial limitation of the terraced house itself, with a spatial void at its core. This element, albeit traditional by its nature, had become the most prominent element in terraced houses composed of a form-space system (Gausa, 1998; Moneo, 1978) with the potential for a unique program. Hypothetically, a form-space system provided a basis for typological manipulation, as observed in the second research objective. At the same time, a ‘program’ could be a new direction of transformation, as stated in the third objective.

Powell’s proposition, which is constructed by his observation of the latest terraced modification trends in Malaysia, is critical in interpreting the existence of a systematic typological manipulation. In his book, “Terraced Transformation in the Tropics” (2021), all 20 terraced houses feature adaptive solutions concerning tropical contemporary lifestyle through the sectional element of ‘void’. While this could be in the form of a courtyard, air well, creative vertical circulation of unique staircases and slides, or double volume spaces, the void creates a seamless integration to a deep, narrow layout, allowing vertical-horizontal flow of spaces beyond function, hence an ‘open section’ of new spaces. Critical to this interpretation, Gausa (1998) argued that ‘void’ as ‘architectonic material’ brings with it the obligation to invent new forms of intervention. Acting as an operative dissipation of the built mass, the void, due to its vacant quality, is interpretable as an open force field for a new system of occupation. Correspondingly, it tends to be more organic and quasi-spontaneous (Gausa, 1998). Hence, the ‘void’ establishes a system of typological manipulation for a terraced house.

Analysis reveals that the configurational pattern of the voids system led to programmatic relations. In the study of ‘actual project’ cases, the five types of void configuration (Figure 2) revealed 12 programmatic relations (Figure 3) demonstrated by the morphological transformation of a typical unit (B1) into multiple programmatic contexts. This indicates the significance of an adaptive design framework through the void of ‘composition-forms-programs’ - a design transformation that responds to the third objective. Accordingly, it justifies the relevance of this study. Moreover, it also justifies the typological logic of void (Carl, 2011; Gausa, 1998), which nurtured a dynamic context of agency (Chi, 2021) through a pragmatic perspective of an actor (Kärrholm, 2013), which is indicatively human-centric.

In the context of living, this trajectory transformation represented by the adaptive design framework suggests a blended version of sustainable and adaptive living. It facilitates a continuous personalization process in ensuring the state of “person-environment congruence” that demands users’ participation in their homemaking (Jusan and Sulaiman, 2005). Normalization of human needs (Leitão, 2022) may be the reason why a standard terraced house may address the common needs of the masses but has never been able to cope with its arising changes. Particularly in post-pandemic, it is evident that the original idea of living is now shifting. Workers expect the continuation of WFH in hybrid mode beyond the COVID-19 pandemic (Pongprasert and Chatrkaw, 2023). This phenomenon expands the economic avenues and opportunities, enriching the ‘non-physical’ functions of a house as a ‘venue for self-development processes’ (Tutuko and Shen, 2014).

While the spatial void programs justified the physical transformation often captured in a unilaterally modified terrace, the notion of self-development as a programmatic strategy beyond needs is collectively evident in the formation of the prototype version. This is evident through ‘desire-based design’ (Figure 4) - an agentic design framework towards programmatic stimulation linked to the third objective. Consequently, this phenomenon is encapsulated by the agency in the following aspects: Desire by the Absence of Damage Needs, Home Micro-Economic, Optimizing Space/Maximizing Value, and Personalization-Customization. These aspects denote changes in the social culture by activating distinguished living operation, hence its formal manipulation of type (Carl, 2011), into agentic formality potential for dynamic events (Kärrholm, 2016; Koch, 2014). It suggests a new reinterpretation of renovation culture (Saji, 2012) through a spatial program rooted in user experience and value maximization and not merely an enlargement modification. This potential value could be invested in developing a programmatic terraced house.

In both cases, user preferences are at the core of the transformation, activating the agentic design framework through ‘desire-based design’ and the adaptive design framework established in the void of ‘composition-forms-programs,’ justifying each manipulation of design attributes aspires by the future patterns (prototype) into spatial void formalities (actual). Note that this process is specialized within the context of terraced typology due to its layout limitation.

This study contributes to categorizing the transformation process into the following sequence: 1) the convention and typicality of attributes (‘standard’), 2) the manipulation of attributes (‘typological manipulation’), 3) the composition of attributes (‘typological pattern’) and 4) new relationship or correlation between attributes (‘spatial transformation’). Various configurations of these components indicate the potential of the terraced house typology as an agent of change for its future becoming.

In addition, the study is methodologically designed to observe a series of specialized case studies in Malaysia in the form of a design competition and a curated compilation. This is where the designer demonstrates novel design concepts as the transformational actor rather than the broader scenario of evolutional strategy practiced in the typical Malaysian terraced house. As a delimitation criterion, the focus remains on deliberate design strategies from the designers’ perspective which already includes homeowners’ considerations.

As a mass-produced commodity, the primary role of terraced house to provide shelter and a good quality of life has been overshadowed by cost-effectiveness and a push for high turnover. Such priorities have compromised its response to the dynamic needs of the user in terms of spatial design. Defined by specific attributes in site planning, spatial layout and configuration, building program, dimensions (measurements), and built form, these elements of ‘convention’ form the attributes of transformation in the terraced house that manifest in spatial patterns more intrinsically, redefining the tectonic expression of the terraced house.

The case study analysis reveals that human-centric priorities define the reality of application. Within these parameters, the interpretation of terraced house transformation is based on the design framework that integrates (1) agentic attributes through the notion of ‘desire-based design’ manifested by the agency of Desire by the Absence of Damage Needs, Home Micro-Economic, Optimizing Space/Maximizing Value and Personalization-Customization and (2) adaptive attributes resulted from the eccentric value of void driven by ‘composition-forms-programs.’ The study concludes that ‘programmatic’ adaptation is key in driving the future of terraced house typological transformation. Hence, providing a new context for sustainability discourse pertaining terraced house design within the realm of human-spatial behavior.

Conceptualization, M.F., K.K., and P.M.B.Z.; methodology, M.F., K.K., and P.M.B.Z.; investigation, M.F., and K.K.; resources, M.F.; data curation, M.F., and N.A.A.N.; writing—original draft preparation, M.F., and K.K.; writing—review and editing, M.F. and K.K.; supervision, M.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of the paper.

The authors would like to thank Universiti Teknologi MARA Cawangan Selangor (UCS) in collaboration with Research Management Centre Universiti Teknologi MARA (RMC – UiTM) for funding this paper under the Career Development Grant Initiative 2020.

Table 1 (Contd.) Diagrammatic sectional drawings illustrating the spatial void as a critical element in determining typological patterns of mid-terraced houses, synthesizing selected case studies presented in the book Terrace Transformations In The Tropics (2021). (Source: Author)