2013 年 53 巻 8 号 p. 1386-1391

2013 年 53 巻 8 号 p. 1386-1391

Laboratory experiments were carried out to investigate non-metallic inclusions and microstructures in Zr–Al deoxidized low carbon steel. Contents of [Zr] in the steel samples were of different levels while [Al] varied in the range of 0.0012–0.0032%. It was found that inclusions and the developed microstructures varied greatly with the change of [Zr] in steel. In the high [Zr] (0.072%) steel sample with [S] about 0.012%, the produced ZrO2 inclusions in deoxidization favored the uniform precipitation of MnS and all inclusions were composed of dual phases of ZrO2+MnS. Microstructures consisted of pearlites and ferrites after water quenching directly from liquid to solid. Ferrites developed by ZrO2+MnS inclusions were not observed. With [Zr] at a medium level about of 0.0085% and [S] at about 0.012%, complex (ZrO2–TiOx)–(Al2O3–SiO2–MnO–(MnS)) inclusions were formed. The microstructures of steel were characterized by fine and interlocked intra-granular ferrites (IAF). SEM observation indicated that those complex inclusions were good nucleation sites for IAF. In the [Zr] steel sample with low [Zr] of about 0.0008% and [S] of about 0.0017%, very typical IAF was also induced by the complex (MgO–Al2O3–SiO2–MnO) inclusions of very high number density.

Heavy steel plates are widely applied for high buildings, offshore structures, pipelines and oil vessels, and so on. Control of MnS inclusions, especially morphology modification, is known to be very important because elongated MnS stringers after rolling degrade mechanical properties in the transverse direction and induce HIC or SCC in these low carbon steels.1,2,3,4,5) Moreover, the thicknesses of these steel plates are increasing with the need for higher strength and toughness. As a result, much larger energy is input during welding for higher efficiency in fabrication. One big problem is grain coarsening in the HAZ (heat affected zone) after welding, which deteriorates toughness.6,7) Therefore, the significance of microstructure refinement in the HAZ had been well recognized; for this problem, acicular ferrites have been found be very helpful.8)

In the 1990s, Takamura and Mizoguchi9,10) proposed the technical concept of “oxide metallurgy” by utilizing inclusions to develop intra-granular acicular ferrites. They pointed out that inclusions with the proper chemical composition, size distribution, and number density can act as heterogeneous nucleation sites for new phases and can refine the microstructure of steel, for example, as inoculants for ferrites within prior austenite grains.11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18) From this point of view, steel compositions, deoxidization methods, refining slags, cooling rates, etc. are very important; all of these directly affect the types, sizes and number density of inclusions.

Zr is an element with strong affinity to oxygen, nitrogen, sulfur, etc. in steel; any produced inclusions have great influence on steel. MnS inclusions were found to prefer to precipitate on complex oxides produced in Si–Mn–Zr deoxidization when Takamura et al.10) proposed the concept of “oxide metallurgy”. In recent years, Suito et al. intensively studied inclusions produced in Zr deoxidized carbon steel and Fe–Ni alloys as well as the influences of inclusions on what is called microstructure refinement.19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27) Moreover, they mainly focused on the pinning effect of inclusion at grain boundaries. Formation of intra-granular ferrites in the HAZ by inclusions in Zr–Ti deoxidized steel was mentioned by those researchers, but much less attention was paid to the concept.28) Chai et al.29) reported that Zr addition into a Ti-killed steel plate effectively refined the HAZ microstructure in ship plates after welding; they found that the formed ZrO2+MnS complex inclusions could not induce acicular ferrite. Guo et al.30) found that the addition of Zr into Al-killed pipeline steel can usefully enhance the impact toughness of the HAZ in welded steel plates; however, the nucleation of intra-granular ferrites on the ZrO2+MnS dual phase inclusions was observed, which was inconsistent with the results of Chai et al.29) Wu et al.31) found that the addition of Zr into Al-killed Ti-bearing ship plates can greatly increased the impact toughness of the HAZ. The related typical works of oxide metallurgy from the past are briefly summarized in Table 1. There have also been other studies on inclusions in steel with added Zr. For example, zirconium sulfides in resulfurized free-cutting steel were reported to minimize the aspect ratio of sulfides.32) Zirconium carbonitrides effectively prevent austenite grain growth in Al-killed high strength low alloy steel and low carbon bainite steel.33,34,35,36) By comparison, zirconium oxides formed in Zr-deoxidization were much more intensively studied.

| Year | Authors | Metal | Deoxidation | [Zr]/ppm | Purpose | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | Takamura et al. | low C steel | Zr | 20, 100 | A1 | 9 |

| 1990 | Mizoguchi et al. | low C steel | Zr | 120 | B | 10 |

| 2006 | Suito et al. | Fe–10%Ni | Zr | 116–633 | A1 | 19 |

| 2006 | Suito et al. | Fe–10%Ni | Zr | 87–95, 1.7–99.2 | A4 | 20, 23 |

| 2006 | Suito et al. | Fe–10%Ni, Fe–10%Ni–1%Mn | Zr | 45.5–89.9 ([S]:19–433) | A4, B | 22 |

| 2006 | Suito et al. | Fe–10%Ni | Zr | 800–1200 (target) | A1, A4 | 24 |

| 2006 | Suito et al. | Fe–10%Ni, Fe–0.5%C–1%Mn, Fe–0.3%C–1%Mn–1%Ni, Fe–0.2%C–0.02%P, Fe–0.15%C–1%Mn–1%Ni | Zr | 1–1080 | C1 | 21 |

| 2006 | Suito et al. | Fe–10%Ni, Fe–0.2%C–0.02%P | Zr | 1.3–1800 | C1 | 25 |

| 2008 | Suito et al. | Fe–10%Ni | Zr/Ti | 11–1166 | C1 | 26 |

| 2008 | Suito et al. | low C steel(1%Ni) | Zr | 1, 38 | C1 | 27 |

| 2008 | Guo et al. | Pipeline steel | Zr | 0, 150 | D | 30 |

| 2011 | Suito et al. | low C steel | Zr, Ti/Zr, Ti/Mg/Zr, Al–Ti/Zr | ~233 | C2 | 28 |

| 2012 | Wu et al. | low C steel | Al killed Zr bearing | 0, 100 | C2 | 31 |

Note: A—Inclusion characterization: size distribution (A1), number density (A2), composition (A3), dispersion (A4);

B—Effect on MnS;

C—Effect on microstructure: solidification and grain boundary pinning (C1) and development of IAF (C2);

D—Mechanical property

Therefore, there have been many works on inclusions in Zr deoxidized steel and some studies for Ti–Zr and Al–Zr complex deoxidized steels. The produced inclusions in Zr deoxidization were proved to be very effective in pinning the grains. By comparison, the effects of inclusions on the development of intra-granular ferrites were much less studied. Moreover, it is particularly well known that aluminum is usually contained in alloys; aluminum can greatly affect the formation of inclusions, and thus probably the microstructure refinement of steel. Although the effect of the addition of Zr in Al-killed low carbon steel on the toughness has been studied, the formation of inclusions in Zr–Al complex deoxidization can be expected to be different and studies on inclusion influence on the microstructures have been only rarely seen. Furthermore, there are some disagreements on observation results on the effects of ZrO2+MnS complex inclusions on the development of intra-granular ferrites. As a result, experiments were undertaken in the present study to investigate the effects of the produced inclusions in Zr–Al deoxidization in low carbon steel; the microstructures of the steel were also characterized.

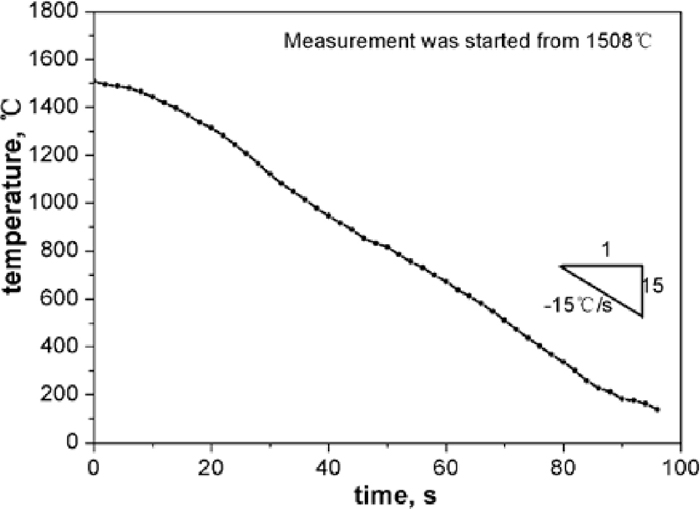

Experiments were carried out in a vertical electrical resistance furnace with MoSi2 heating bars. Three experiments were performed; one of them involved slag refining (50 g, CaO–SiO2–Al2O3 ternary slag with basicity about 2.5 and Al2O3 about 25%). During the experiments, high purity argon gas flow was introduced into a sealed Al2O3 reaction tube at all times. In each experiment, 1 kg of electrolyte Fe was charged into a MgO crucible and set at the even temperature zone of the furnace. When the melt was heated to 1873 K, Fe2O3 powder was added into the melt to increase the initial oxygen in the melt. Then, Zr and Fe–Al–Mn alloys were added for deoxidization. About twenty minutes after deoxidation, alloys like FeC, electrolyte Mn, FeS, crystal silicon, etc. were added into the steel melt for composition adjustment. After homogeneity of chemical composition was achieved, the crucible was taken out of the furnace and water quenched rapidly with a cooling rate estimated at about 15 K/s. For the estimation of the cooling speed, a special experiment was done in which a thermocouple was inserted into the cooling sample to record the change of temperature with time, with results as shown in Fig. 1. Because the sample had to be picked up from the tube before it was put into water for quenching, the measurement was started from about 1508°C, when the thermocouple was inserted into the sample.

Change of temperature with time of the sample during water quenching from liquid to solid.

The obtained steel samples were prepared for chemistry analysis, inclusion inspection, and microstructure observation. Soluble contents of Al and Zr were measured using ICP method. Compositions in this article are all given in weight percentage unless specifically stated. Disc samples were transversely sectioned and mirror polished for inclusion inspection using an automatic secondary electron microscope with energy disperse spectrum (ASPEX PSEM Explorer). Microstructures of the samples etched by 3%Natal solution were observed by both optical microscope (LEICA DM6000M) and SEM methods.

Chemical compositions of the steel samples are given in Table 2. [Al] contents in the three samples are 0.0012, 0.0024, and 0.0032%. The [Zr] contents are 0.0720, 0.0085, and 0.0008%, respectively. Thus, the samples are classified as high Zr, medium Zr, and low Zr samples in the present paper. Because of the top slag refining, sulfur content in the low Zr steel sample is much lower than that in the other two steel samples.

| Sample | Contents (mass%) | Slag refining | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | Si | Mn | S | Al | Zr | ||

| High Zr | 0.15 | 0.24 | 1.01 | 0.0120 | 0.0012 | 0.0720 | No |

| Medium Zr | 0.08 | 0.20 | 0.98 | 0.0120 | 0.0024 | 0.0085 | No |

| Low Zr | 0.17 | 0.12 | 0.92 | 0.0017 | 0.0032 | 0.0008 | Yes |

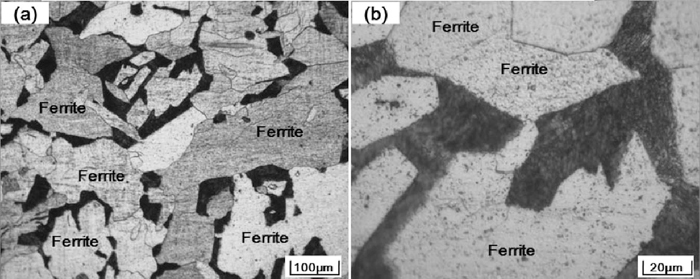

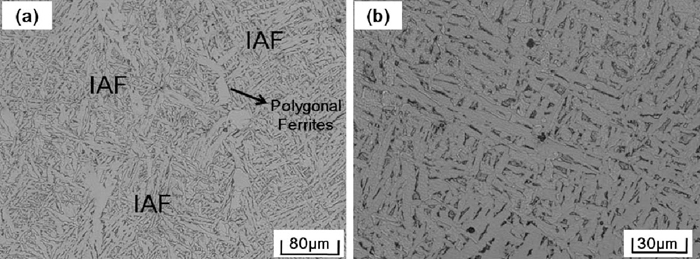

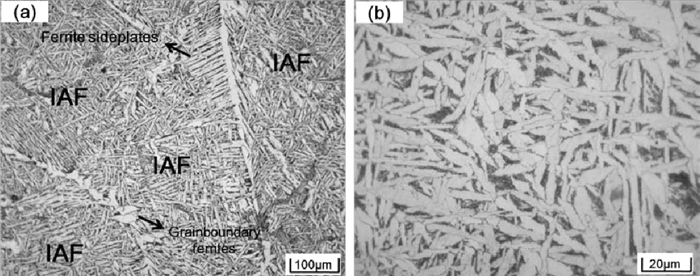

Optical microstructures of the steel samples are presented in Figs. 2, 3 and 4. It can be seen that microstructures of the three steel samples mainly consisted of ferrites. However, the morphology of the formed ferrites in three samples is distinctive according to the level of Zr contents. In the high Zr sample, ferrites are in chaotically polygonal shapes, with sizes usually more than 200–300 μm, as shown in Fig. 2. In the medium Zr sample, very fine acicular ferrites were found to hvae developed; these are called inters. Some polygonal shaped ferrites are also observed, as shown in Fig. 3(a). Images of higher magnification indicate that these acicular ferrites appeared as interwoven long strips, as shown in Fig. 3(b). In the low Zr sample, interlocked lenticular shaped ferrites formed with prior austenite grains are the main feature of the microstructure. Sheaf morphology side plate ferrites and polygonal allotrimorphic ferrites nucleated and developed from the prior austenite grain boundaries are also formed in this sample, but they are only a small fraction, as shown in Fig. 4(a). These lenticular shaped ferrites have different growth orientations and, with two dimensional size of mainly less than 50 μm, resulted in an intersecting image under optical microscope observation, as shown in Fig. 4(b) at larger magnification.

Microstructures of high Zr sample: (a) lower magnification, (b) higher magnification.

Microstructures of medium Zr sample: (a) lower magnification, (b) higher magnification.

Microstructures of low Zr sample: (a) lower magnification, (b) higher magnification.

Nucleation of ferrites on non-metallic inclusions was observed in the medium Zr sample and the low Zr sample, while it was not detected in the high Zr steel sample. Figure 5 shows the observation results of the microstructure by SEM; Fig. 5(a) provides an image under back scattering mode. As can be seen, the ferrites in the high Zr steel sample were very large in size and in irregular polygonal shapes. In particular, nucleating of ferrites on inclusions was not observed in this steel sample. However, by contrast, the development of ferrites by inclusions was observed frequently in the medium Zr steel sample and the low Zr steel sample. As shown in Fig. 5(b), the inclusion at about 2 μm acted as the heterogeneous nucleus of the ferrites. EDS results indicate that, in terms of overall chemistry, the inclusion was composed of ZrO2–TiOx–SiO2–MnO. The inclusion shown in Fig. 5(c) was a little larger, at about 4–5 μm; ferrite laths developed from it and grew in a radiative way. Based on the EDS peaks, it can be seen that the chemistry of this inclusion was also very complex, and that it was composed of an MgO–Al2O3–SiO2–MnO system.

Observation of nucleation of ferrites on inclusion in high Zr, medium Zr, and low Zr steel samples.

It is particularly known that the formation of IAF is very complex. Several factors can contribute to the formation process, including steel additives like [C], [Si] and [Mn], and inclusions and thermal cycles of the steel, such as cooling rate. In conventional heat treatment, prior austenite grain size also plays an important role during the phase transformation between α-Fe and γ-Fe. In the present experiments, the chemical compositions of the steel were not completely the same in terms of [C] and [Si]. Nevertheless, in the high Zr steel sample and the medium Zr steel sample, the compositions were very similar except for the levels of carbon, which were about 0.15 and 0.08%, respectively. Therefore, it can be predicted that L-δ-γ-α phase transformations will occur in both samples during quenching. Other factors, like solidification related parameters, could be considered the same. However, as mentioned in the sections above, the microstructures in the high Zr and the medium Zr samples were completely distinctive. As result, it can be cautiously but reasonably asserted that non-metallic inclusions were the main reason contributing to the big differences in microstructures of the three samples.

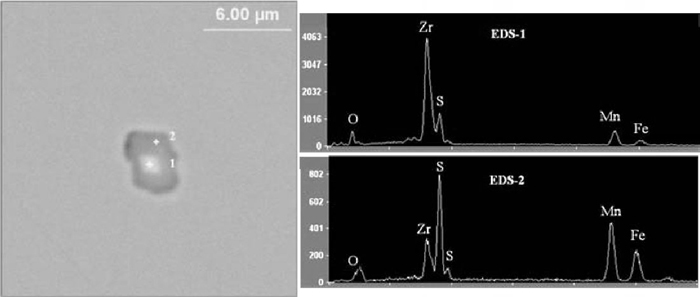

3.4. Comparison of the Formed Non-metallic Inclusions: Chemistry, Size Distribution and Number DensityUsing an automatic SEM EDS (ASPEX Explorer), a large area on the surface of each sample was selected for inclusion inspection. About 4000 inclusions were randomly inspected in each sample. Thus, their important characteristics, such as the sizes, chemistry, and number density were obtained. SEM-EDS analysis results of inclusions in the three steel samples are given in Figs. 6, 7, and 8, respectively. It can be seen that the chemistry of the inclusions varied with the change of Zr contents in the three steel samples. In the high Zr steel sample, all the detected inclusions are found to consist of dual phases, viz., with polygonal ZrO2 in the center wrapped by an MnS outer skin, as shown in Fig. 6. This result agrees with that reported by Mizoguchi et al.,10,18) who found that MnS preferred to precipitate on ZrO2, resulting in finer sizes and uniform dispersion. This phenomenon can be attributed to the similar lattice parameters and good lattice coherence between MnS and ZrO2 [30]. It means that although no IAF was developed at high Zr content in steel, the formed ZrO2 inclusions were still very useful in controlling the precipitation of MnS, which is also very important for heavy steel plates.

Typical inclusion in high Zr steel sample: ZrO2+MnS.

In the medium Zr steel sample, two kinds of inclusions were detected. The majority of them were complex in chemistry, characterized by ZrO2–TiOx inclusion surrounded with an Al2O3–SiO2–MnO–(MnS) surface layer, as shown in Fig. 7(a); the central part of this kind of inclusion had higher Zr and Ti and less Si, Mn, Al, and S; the outer part had higher Si, Mn, Al, O, and S and lower levels of Zr and Ti. Titanium was not added in the present study. Therefore, the source of titanium observed in inclusions may be from the added alloys as impurity. The other kind of inclusions was single MnS, but these occupied a small fraction. The single MnS had spherical or near-spherical shape, as shown in Fig. 7(b). It also can be found that although the sulfur contents were the same in the high Zr and medium Zr steel samples, no singular MnS inclusions were formed in the high Zr steel sample, which means that ZrO2 actually was very helpful in preventing formation of MnS which can form elongated strings after rolling and which is very negative for heavy steel plates.

Typical inclusions in medium Zr steel sample: (a) (ZrO2–TiOx)–(Al2O3–SiO2–MnO–(MnS)), (b) MnS.

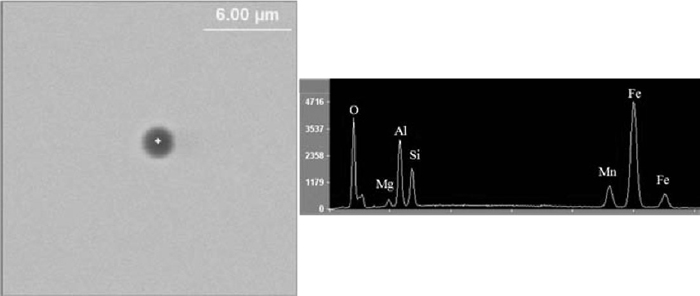

With zirconium content greatly decreased to 0.0008% in the low Zr steel sample, no ZrO2 is contained in the inclusions. The inclusions are mainly composed of the MgO–Al2O3–SiO2–MnO system; MnS was seldom detected in inclusions because of the very low sulfur content in the steel. Distinctive from inclusions in the high Zr and medium Zr samples, inclusions in the low Zr sample are homogeneous, as indicated in Fig. 8.

Typical inclusion in low Zr steel sample: (MgO–Al2O3–SiO2–MnO).

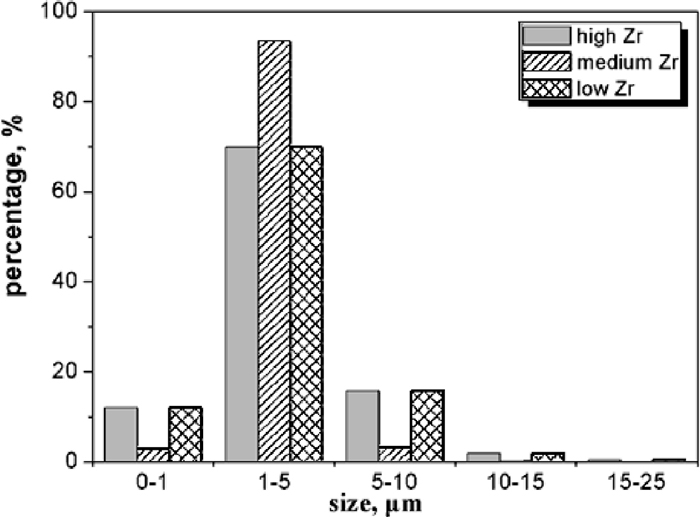

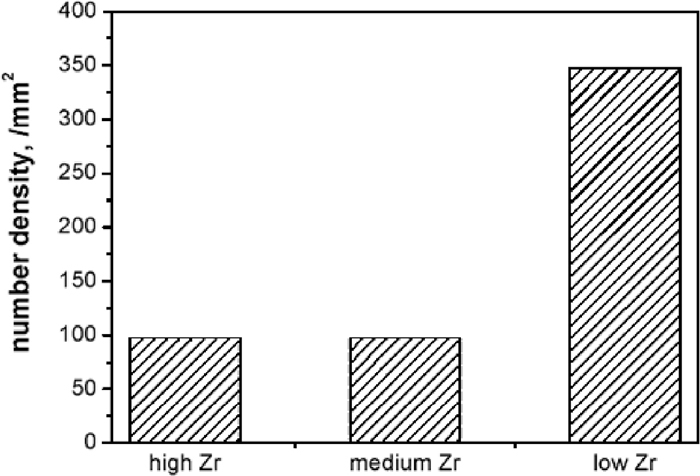

Size distributions of inclusions were also analyzed and results are shown in Fig. 9. As can be seen, the size of inclusions in the three steel samples are mainly within 5 μm. Percentages of inclusions within 1 μm in high Zr, medium Zr, and low Zr were about 12, 3 and 12%, respectively. Fraction of inclusions in the range of 1–5 μm occupied the largest proportions in all the steel samples, or about 93% in the medium Zr steel sample and about 70% in the other two samples. Inclusions with size varying in the range of 5–10 μm are about 16, 3 and 16% in high Zr, medium Zr, and low Zr, respectively while inclusions with size exceeding this range are very rare. Number density of inclusions in the steel samples was compared, with results given in Fig. 10, this data was estimated by dividing the total number of inclusions by the observed area. As can be seen, number density of inclusions was about 97 per mm2 in both the high and medium Zr steel samples. However, inclusion number density was much high in the low Zr steel sample, at about 347 per mm2.

Size distribution of inclusions in high Zr, medium Zr, and low Zr steel samples.

Number density of inclusions in high Zr, medium Zr, and low Zr steel samples.

Hence, the inclusions in the three samples mainly had sizes in the range of 1–5 μm. This means that the size of the inclusions was not the main reason for the difference in the development of IAF by inclusions. As the number density of the inclusions was nearly the same in the high Zr sample and the medium Zr sample, it can be reasonably inferred that the inclusion chemistry is responsible for there being no IAF in the high Zr sample while there is good IAF in the sample with a medium level of Zr. Therefore, it can be inferred that (ZrO2–TiOx)–(SiO2–MnO–Al2O3–(MnS)) inclusions in the medium Zr steel sample are useful in developing ferrites. Although ZrO2+MnS inclusions cannot induce intra-granular ferrite in the high Zr steel sample, there are very good heterogeneous nucleation sites for MnS. By comparison, it is not so clear that whether it is number density or chemistry of inclusion in the low Zr steel sample that contributes more to the formation of IAF. On the other hand, it can be seen from the results that the lower level of [Zr] in the steel was definitely not bad for the development of intra-granular ferrite. Moreover, further investigations are needed to elucidate the optimized steel chemistry for IAF in Zr containing steel.

Experiments were carried out in the lab to investigate the development of intra-granular acicular ferrite (IAF) by inclusions in Zr–Al deoxidized steel microstructure refinement. Three samples were used with different contents of [Zr] while [Al] varied in the range of 0.0012–0.0032%. The results are summarized as follows.

(1) In the steel sample with high [Zr] of about 0.072%, the formed inclusions are mainly ZrO2; these are good heterogeneous nucleation sites for MnS precipitation during solidification but are not potent for the development of IAF. The microstructure was found not to consist of IAF.

(2) In the medium steel sample with [Zr] of about 0.0085%, the produced inclusions were mainly complex (ZrO2–TiOx)–(SiO2–MnO–Al2O3–(MnS)) inclusions and some singular MnS inclusions. The formed (ZrO2–TiOx)–(SiO2–MnO–Al2O3–(MnS)) inclusions are good nucleation sites for IAF. As a result, very fine interwoven acicular ferrites were found to have developed.

(3) In the low Zr steel sample with [Zr] of about 0.0008%, MgO–Al2O3–SiO2–MnO complex inclusions were produced with a very high number density of about 347 per mm2. The formed inclusions also induced very nice IAF in the steel.