2013 年 53 巻 8 号 p. 1411-1419

2013 年 53 巻 8 号 p. 1411-1419

The aggregation behavior of desulfurization flux in hot metal desulfurization with mechanical stirring was investigated by small-scale hot metal experiments. Desulfurization flux added from the top aggregated in the hot metal during stirring, reducing the interfacial area between the flux and hot metal, which had a large effect on the desulfurization rate. The size of aggregated slag can be estimated using an aggregation model based on granulation theory. The obtained aggregation rate constant, ka, is 4.5–40.9×10–11 (m3/s). The interfacial area between flux and hot metal can be estimated using the aggregation model, which can also estimate desulfurization behaviors under various conditions. The obtained slag size after desulfurization agreed with the calculated slag size in the equilibrium state, which is highly dependent on stirring conditions. The aggregation rate in commercial-scale (270 ton) desulfurization is larger than that in small-scale experiments due to the difference of their stirring energies.

In recent years, lowering the sulfur content of hot metal in the stage of hot metal pretreatment has become increasingly important not only for meeting demand for high purity steels, but also for reducing slag generation. Many investigations have been reported1,2,3,4) on techniques for increasing desulfurization flux utilization for desulfurization in hot metal with mechanical stirring (KR method5)). Takaoka et al.3) investigated the effect of the particle size of desulfurization flux on the hot metal desulfurization rate. In the experiments, the desulfurization rate with finer particles (≦45 μm maximum size) was higher than that with larger particle (5.6–8 mm). However, the difference in the desulfurization rates with finer and larger particles was smaller than that estimated by the difference in the interfacial area calculated from the particle sizes. Takaoka et al.3) pointed out that this phenomenon was caused by aggregation of desulfurization flux in hot metal. The authors reported that both enhancing particle dispersion and avoiding particle aggregation are important for enhancing desulfurization efficiency.6) However, particle aggregation behavior and its influence on desulfurization behavior have yet not been clarified.

In this work, the aggregation behavior of desulfurization flux and its influence on the desulfurization rate were studied by hot metal desulfurization experiments with a 70 kg-scale induction furnace. Many conditions have an influence on flux aggregation behavior, such as chemical composition, size, flux consumption, hot metal temperature, and stirring conditions. In this work, the effects of flux consumption and the rotation speed of an impeller on flux aggregation were investigated. Flux aggregation behaviors were analyzed by a mathematical model based on granulation theory, and the effect of the interfacial area of aggregated flux on the desulfurization rate was evaluated.

The experimental apparatus was the 150 kg-scale high frequency induction furnace shown in Fig. 1. Table 1 shows the experimental conditions. 70 kg of hot metal (4–5mass%C–0.04mass%S) was melted in a magnesia crucible (250 mm inner diameter × 500 mm depth), and the temperature was set at 1573 K. The hot metal was stirred by a carbon impeller (4 blades, 100 mm diameter × 50 mm height), which was immersed in the hot metal and rotated in the range of 450 rpm to 850 rpm. The impeller immersion depth was set at 150 mm. Immersion depth is defined as the distance between the molten hot metal surface without stirring and the bottom of the impeller. Desulfurization flux (95mass%CaO–5mass%CaF2, ≦1 mm maximum size, 250 μm average size) was added from the top of the crucible. Hot metal samples were taken at specific intervals in order to evaluate the desulfurization rate.

Experimental apparatus for 70 kg-scale hot metal experiments.

| Furnace | 150 kg IF ϕ250 mm | |

| Metal | Chemical composition | Fe - 4–5 mass%[C] –0.04 mass%[S] |

| Weight | 70 kg | |

| Depth | 204 mm | |

| Rotation speed | 450–850 rpm | |

| Impeller | Height | 50 mm |

| Diameter | 100 mm | |

| Blade width | 25 mm | |

| Impeller immersion depth | 150 mm | |

| Temperature | 1573 K | |

| Flux | CaO–5mass% CaF2 ≦1 mm maximum size, 5 , 10 kg/t Al ash (0.3 kg/t) | |

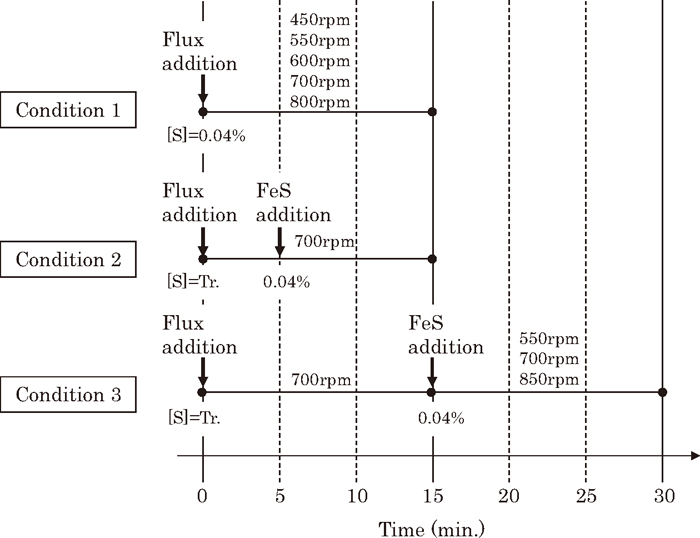

Figure 2 shows the experimental pattern. In Condition 1, the initial [S] was set at 0.040 mass%, desulfurization flux consumption was 5 or 10 kg/t, and the rotation speeds of the impeller were set in the range of 450–800 rpm. In Condition 2, the initial [S] was set at trace, and FeS equivalent to 0.040 mass% was added after 5 minutes. In Condition 3, the initial [S] was set at trace, FeS equivalent to 0.040 mass% [S] was added after 15 minutes, and the desulfurization rate was evaluated between 15 and 30 minutes. During this period, the rotation speed of the impeller was set at 550, 700, or 850 rpm.

Experimental patterns for 70 kg-scale hot metal experiments.

Slag samples were perfectly taken and their size distribution was measured at 1, 3, and 5 minutes after flux top addition in order to evaluate the flux aggregation behavior. Slag samples were screened and separated into 11 size classes: ≦0.5 mm, 0.5–1.0 mm, 1.0–2.8 mm, 2.8–4.0 mm, 4.0–4.75 mm, 4.75–5.6 mm, 5.6–6.3 mm, 6.3–8.0 mm, 8.0–9.5 mm, 9.5–11.2 mm, and ≧11.2 mm. The average size, Ds, was obtained by Eq. (1).

| (1) |

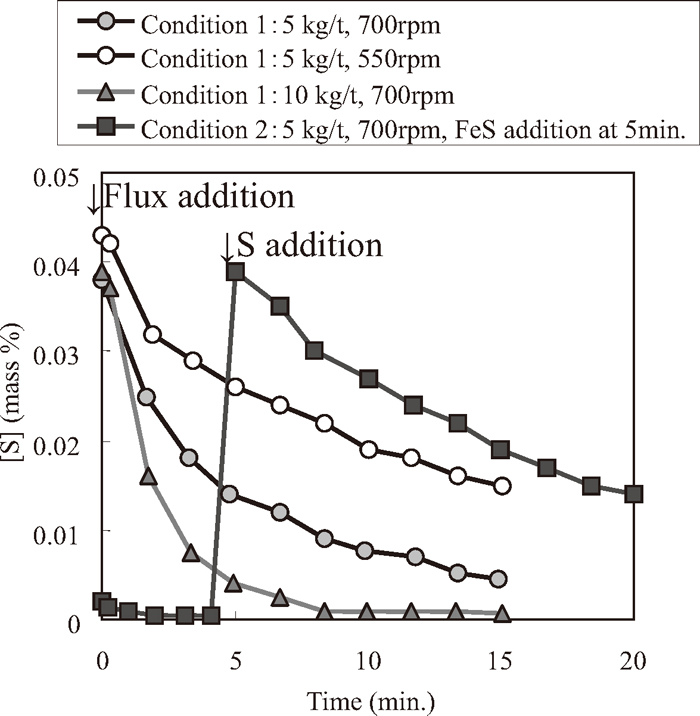

Changes of [S] and [S]/[S]i ([S]i: initial [S]) as a function of time (Conditions 1 and 2) are shown in Figs. 3 and 4, respectively. In Fig. 3, the desulfurization reaction proceeded and the desulfurization rate decreased as [S] decreased. In Fig. 4, the slope of each condition corresponds to the pseudo first order reaction rate. The desulfurization rates decreased with time. The desulfurization rate under Condition 1, 700 rpm and flux consumption of 10 kg/t, was larger than that under Condition 1, 700 rpm and flux consumption of 5 kg/t. The desulfurization rate under Condition 1, 700 rpm and 5 kg/t, was larger than that under Condition 2, 700 rpm and 5 kg/t. Under Condition 2, the initial [S] was set at trace and FeS was added after 5 minutes. Therefore, the desulfurization flux was considered to aggregate during 5 minutes, which means the interfacial area became smaller than that under Condition 1.

Desulfurization behaviors in hot metal experiments (Conditions 1 and 2).

Changes of [S]/[S]i in hot metal experiments (Conditions 1 and 2).

The desulfurization rate can be expressed as shown in Eq. (2) by assuming that the rate-controlling step is the mass transfer of [S] in the hot metal. Here, Ks is the apparent desulfurization rate constant. Figure 5 shows the changes of Ks, which were obtained by calculating Ks for each sampling interval. Under both Conditions 1 and 2, flux consumption 5 kg/t and 700 rpm, Ks decreased with time. Ks was larger under Condition 1 than under Condition 2. Figure 6 shows the relationship between the [S] content and Ks. In Fig. 6, the Ks data are the same as those in Fig. 5, and the [S] values on the vertical axis are the average [S] between the initial and final contents at each interval. Ks did not depend on [S]. This means that Ks is significantly influenced by the changes in the interfacial area, which are caused by flux aggregation.

| (2) |

Ks changes as a function of average time in hot metal experiments (condition 1 and 2).

Changes of Ks as a function of [S] in hot metal experiments (condition 1 and 2).

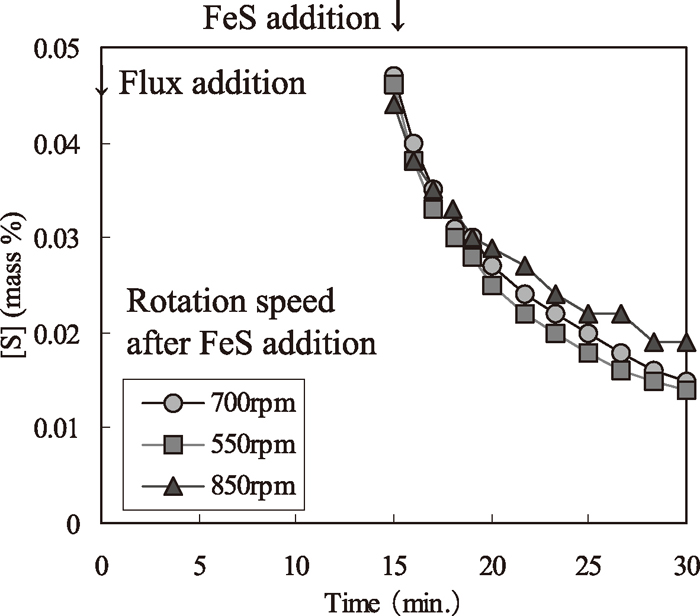

Desulfurization behaviors in hot metal experiments (Condition 3).

Figure 8 shows the slag size distribution after flux addition (at 1 min, 3 min, 5 min and 15 min) in hot metal experiment for Conditions 1, 5 kg/t and 700 rpm. Although the average size of the added flux is 250 μm, the proportion of finer slag smaller than 500 μm decreased, and the proportion of larger slag of 1.8–2.8 mm increased. After stirring for 15 minutes, the average aggregated slag size became 1.5 mm as shown in Fig. 9. Figure 9 shows the change of the average slag size as a function of time. Under all conditions, the average slag size increased during stirring. The change of the average slag sizes under Condition 1 with flux consumptions of 5 kg/t and 10 kg/t were the same. Therefore, the effect of flux consumption on the aggregation of flux is considered to be small.

Changes of particle size distribution as function of time in hot metal experiments (Condition 1).

Changes of average particle diameter as a function of time.

Mathematical models of inclusions aggregating and floating in molten hot metal have been reported.7,8,9,10) Nakanishi et al.7) calculated the change of inclusion size based on the Saffman and Tunner8) model, which assumed turbulent collision of particles. Lindborg et al.9) reported the behaviors of SiO2 particles in molten hot metal and discussed the change of aggregation size associated with collision based on Stokes’ law. They reported that inclusions 1–3 μm in size are generated and aggregate as 20 μm aggregated particles within 1 minute by both turbulent collision and Stokes’ coagulation. The aggregated particles could float on the molten hot metal surface. In this argument, particles larger than 20 μm are not subject to aggregation in molten hot metal since they can be separated by floating. Miki et al.10) studied the change of inclusion size and density in the RH degasser process. In that research,10) the initial size of the inclusions was 1–3 μm, the final aggregated size was 50–70 μm, and the number density of the aggregated particles in molten hot metal was 1×106/m3, which is equivalent to a volume fraction in molten hot metal of 2.0×10–6–3.3×10–7. In studies of inclusion aggregation in molten hot metal, the ranges of particle sizes and their volume fractions are both small.

On the other hand, the volume fraction of desulfurization flux in hot metal is far larger in the present work. The volume fraction in commercial plant scale experiments4) was calculated to be 1.8×10–2, which is 104 times larger than that of inclusions in molten hot metal. In that calculation, the conditions used for the hot metal were 270 ton weight and 7000 kg/m3 density, and the conditions for the desulfurization flux were 2025 kg weight, 3000 kg/m3 density and 150 μm average size.

Therefore, this work focused on an aggregation model for wet granulation. Takenaka et al.11) investigated the aggregation behaviors of sulfisomidine particles 73.3–79.3 μm in size in a chloroform solution with impeller rotation. In their research, the particles aggregate in the first stage of stirring and their size saturates in the equilibrium state. In the experiments, the volume fraction of particles in solution was 3.6×10–2, which is the same level as in the present work. Capes et al.12) researched the aggregation and dispersion behaviors of solid sand (10–150 μm) in organic liquids and indicated that the particle size in the equilibrium state can be explained by the balance between destructive and cohesive forces acting on the agglomerates. The destructive and cohesive forces depend on a centrifugal force caused by mechanical stirring and granulation strength, respectively. Newitt et al.13) measured the granulation strength of silica sand in a wet condition. The volume fraction of particles and the initial particle size were 3.6–5.0×10–2 and 10–200 μm, respectively, which are the same ranges as in this work.

In the process of hot metal desulfurization with mechanical stirring, desulfurization flux is added from the top of the desulfurization vessel and entrained into the hot metal, and the desulfurization flux then aggregates in the molten hot metal. In this work, the wet granulation model was applied to the behavior of desulfurization flux in hot metal. In this model, the aggregation behavior proceeds while maintaining a balance between the destructive and cohesive forces caused by the centrifugal force caused by mechanical stirring and granulation strength.

4.2. Estimation of Aggregated Slag SizeThe relationship between the interfacial area obtained from the aggregated flux size and desulfurization rate was discussed. First, the flux aggregation behavior was analyzed based on the granulation model. The dispersion and aggregation of particles in a liquid can be expressed by the function of potential energy and the distance between the particles based on their probability of collision. The aggregation behavior of monodispersed particles can be expressed by Eq. (3).14)

| (3) |

Equation (4) can be obtained by integrating Eq. (3) assuming γ=γf, at t=0.

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

| (9) |

| (10) |

| (11) |

| (12) |

| (13) |

Fitting of calculated average particle diameter with measured one to obtain ka under Condition 1.

Relationship between aggregation rate constant, ka, and stirring energy, P.

Iwasa et al.15) investigated the aggregated particle size of desulfurization flux when particles are entrained into hot metal using a water model and hot metal experiments. They15) evaluated that size by adopting the model proposed by Asai,17) who proposed a model for the entraining condition of slag droplets into a metal bath, which is dependent on the interfacial tension between the solid slag and the liquid bath. In that model, the liquid slag phase is assumed to move at a constant velocity. In the present study, slag samples were collected after 1 minute, and the slag size is considered to be similar to that case. Figure 12 shows the relationship between the slag velocity and slag size. Figure 12 shows both the slag size collected after 1 minute and the results reported by Iwasa et al.15) The two lines shown in Fig. 12 were calculated by the Asai model using slag densities of 3000 kg/m3 (true density) and 1150 kg/m3 (apparent density). The horizontal axis of Fig. 12 is the velocity when the particle is entrained into the hot metal. Those velocities were calculated by Eq. (14), which is the axial velocity in a cavity generated by a rotating impeller.

| (14) |

| (15) |

| (16) |

Relationship between velocity and diameter of slag aggregated in small-scale (70 kg) desulfurization experiments and previous work.

Equation (2) can be expressed as Eq. (17) with the interfacial area between flux and hot metal.

| (17) |

| (18) |

| (19) |

| (20) |

| (21) |

Fitting of calculated [S] concentration with measured [S] concentration to determine relative velocity vt under Condition 1.

Comparison of desulfurization behaviors between calculated and measured under Condition 1 and 2.

Comparison of desulfurization behaviors between calculated and measured with impeller rotation speeds of 450, 600, and 800 rpm.

Aoki et al.23) investigated the aggregation behaviors of colloidal particles in a macromolecular electrolyte. In their work, the obtained ka is 1.6×10–18 (m3/s). The aggregation rate constant, ka, of colloidal particles can be expressed by Eq. (22). In that equation, aggregation depends on an interparticle force associated with the potential energy based on the distance between two particles. The calculated ka under the conditions of this work was 2.9×10–18 (m3/s), which was much smaller than the obtained ka (4.5–40.9×10–11 (m3/s)).

| (22) |

Figure 16 shows the relationship between the impeller rotation speed and the aggregated particle size in the equilibrium state, De, which can be calculated by Eq. (10). In Fig. 16, the measured slag size in a commercial-scale (270 ton) vessel is shown in addition to the results of this work. The slag sizes in the case of small-scale experiments were obtained by sampling at 15 minutes after adding the flux and taking an average. In the case of the commercial-scale experiments,4) the slag sizes were obtained by sampling at 10 minutes after adding the flux and taking an average. Both obtained slag sizes are similar to the calculated ones. In the commercial-scale experiments, the obtained slag size was widely spread mainly due to the influence of the initial slag, which was remained even after slag. The obtained slag size for the commercial-scale process was larger than those in this work (small-scale experiments) due to the difference of the rotation speeds, which is consistent with Eq. (10). As shown in Fig. 16, the effect of the impeller rotation speed on De is significant. Therefore, a higher impeller rotation speed is effective for avoiding flux aggregation, in other words, enhancing flux dispersion into hot metal. Figure 17 shows a comparison of the flux aggregation behaviors in small-scale experiments and commercial-scale data.4) Here, the aggregation coefficient of the commercial-scale condition was estimated by Eq. (13). The stirring energy under a commercial-scale condition was calculated to be 300 W/ton. In commercial-scale desulfurization, the slag sample was taken after treatment (10 minutes). In a commercial-scale, the measured slag size was positively deviated from the calculated one. That deviation is caused by the influence of the initial slag, which is remained after slag skimming, and changes of rotation speed and flux consumption. Under the commercial-scale condition, the stirring energy is smaller than that in the small-scale experiments, which means that the aggregation rate in commercial-scale desulfurization is larger than that in small-scale experiments.

Relationship between rotation speed and equilibrium particle diameter, De.

Comparison of aggregated slag size changes between small-scale (70 kg) experiments and commercial-scale (270 ton) data.

The aggregation behavior of desulfurization flux in hot metal and its effect on desulfurization were investigated by hot metal desulfurization experiments. The conclusions are summarized as follows.

(1) Desulfurization flux added from the top of a desulfurization vessel aggregates in hot metal, and this aggregation behavior has a large effect on the desulfurization rate by changing the interfacial area between the flux and the hot metal.

(2) The change of the aggregated particle size was analyzed and evaluated using a granulation model. The obtained aggregation rate constant was ka=4.5–40.9×10–11 (m3/s), which was much larger than that reported in a previous study of colloidal particles in a macromolecular electrolyte.

(3) Desulfurization behavior can be explained by the estimated interfacial area, which is calculated using the aggregation model. The obtained mass transfer rate of [S] was 2.7×10–4 ~ 4.0×10–4 m/s, which is similar to the reported values.

(4) The obtained slag size after 1 minute was smaller than the value calculated by the Asai model, which analyzed slag entrainment based on interfacial tension. The critical slag size when a slag particle is entrained into hot metal cannot be estimated by the Asai model.

(5) The slag sizes after desulfurization in both small-scale experiments and commercial-scale desulfurization agreed with the calculated values obtained using the aggregation model. The slag size after desulfurization is highly dependent on the stirring energy associated with impeller rotation.

A: Interfacial area (m2)

De: Aggregated particle diameter in equilibrium state (m)

Df: Initial added particle diameter (flux diameter) (m)

Ds: Diffusion coefficient of sulfur in hot metal (m2/s)

D: Aggregated particle diameter (m)

di: Particle size (mm)

K: Constant depend on condition of granulation (–)

Ks: Apparent desulfurization rate constant (1/min)

k: Boltzman constant (=1.381×10–23 (J/K))

ka: Aggregation rate constant (m3/s)

km: Mass transfer rate (m/s)

N: Rotation speed of impeller (rpm)

n: Number of particles whose diameter is D (–)

P: Stirring energy (W/t)

Re: Reynolds number (–)

r: Radius of impeller (m)

rc: Radial position (m)

[S]: Sulfur content in hot metal (mass %)

t: Time (second)

u: Axial velocity in cavity (m/s)

Vf: Flux volume (m3)

Vm: Volume of particle dispersed liquid (hot metal) (m3)

vt: Relative velocity of particle compared with hot metal (m/s)

Wf: Total weight of granulates (flux) (kg)

Wm: Hot metal weight (kg)

wi: Weight of each size distribution (kg)

γ: Number of particles in unit volume of liquid (–)

γe: Number of particles in equilibrium state (–)

γf: Initial number of particles (–)

ε: Void ratio in aggregated particles (–)

μ: Viscosity of liquid (Pa·s)

ρf: Particle (flux) density (kg/m3)

ρm: Liquid (hot metal) density (kg/m3)

τ: Interfacial tension between particle and hot metal (N/m)

ω: Angular velocity of impeller rotation (rad/s)