2020 Volume 60 Issue 8 Pages 1803-1809

2020 Volume 60 Issue 8 Pages 1803-1809

Dislocation defects induced by neutron irradiation can degrade the mechanical properties of reactor pressure vessel steel; although the properties can be restored by annealing, this treatment is energy- and time-intensive. A fast and energy-efficient method of decreasing the dislocation density is urgently needed. In this study, electric pulse treatment was applied to damaged A508-3 steel to remove the dislocation defects quickly. The pulsed electric current reduced the dislocation density in a brittle sample and improved the impact toughness. After electric pulse treatment, the ductile–brittle transition temperature was 11.8°C lower. Calculations revealed that the higher temperature around the dislocations and the electron wind force under the electric field decreased the activation energy of dislocation motion, causing the dislocations to move more easily. The dislocation defects can be annihilated as they move, decreasing the dislocation density.

A dislocation defect is an irregularity in the arrangement of one or more columns of atoms in a cubic crystal; the concept was first proposed by Taylor to explain why slipping occurs over a limited region but not over all the atoms in the slip plane.1) Dislocation strengthening is currently one of the most effective strengthening methods. However, a high dislocation density will compromise the ductility and toughness.2,3,4) The mechanical properties of a reactor pressure vessel (RPV) will deteriorate sharply because of the increase in dislocation density after the high-energy neutron beam irradiation in service.5,6,7) Lin et al. tested the Charpy impact energy of A508-3 steel before and after neutron irradiation and found that T41J increased 68°C.5) Marini et al. found that the yield stress of 16MND5 increased by more than 14% after irradiation, and the ultimate tensile stress increased by more than 12%.8) In Pawel’s study, the fracture toughness of various materials all decreased after irradiation to 3 dpa.9) It was shown that the dislocation density in thin foils of RPV steel weld increased after years of neutron irradiation,10) and Cu, Mn, Ni, and Si atoms were enriched at dislocations,11) which resulted in Cu-, Mn-, and Ni-rich clusters and decreased the toughness. Long-duration ex situ annealing treatment can reportedly reduce the matrix defect damage in RPV steel.10,11,12) Miller et al.13) annealed RPV steel with irradiation embrittlement damage at 460°C for 168 h and found that the toughness was restored after annealing. Moreover, the Army SM-1A RPV in the United States14) and Loviisa FPV in the Soviet Union,15) which exhibited embrittlement damage after service, were repaired by annealing, although the reasons for the recovery were not given. The results showed that after annealing, the ductile–brittle transition temperature (DBTT) of the brittle samples recovered from 25% to 100%. However, all of these annealing treatments required a high temperature of 360°C to 480°C and more than 168 h, so a large amount of energy was needed to reduce the dislocation defects. In addition, the use of annealing in production is limited because the embrittlement damage of RPV can be repaired only by putting the heat source inside it, as the RPV cannot be moved. The premise of the annealing recovery is that the reactor cores need to be carried out of the RPV, and the risk and caseload of the carrying are worth considering. Therefore, an energy-saving method for in situ repair of RPVs with irradiation embrittlement damage is needed.

A pulsed electric current has been studied as an instantaneous high-energy input method for materials. An electric pulse is known to affect the microstructural evolution,16,17) recovery and recrystallization,18) phase transformation,19) texture evolution,20) and diffusion.21,22) In a study of the dislocations and mechanical properties, Kim et al.23) treated Al 5052-H32 by a pulsed electric current under uniaxial tension and found that the pulsed current softened the flow stress and increased the elongation dramatically. Kim et al. suggested that an electric current can induce annealing as a distinct role from Joule heating. Tang et al.24) applied electric current to SUS316 steel after tensile fatigue tests and observed that the dislocation density was much lower than that when the electric current was not applied. Liu et al.25) treated AZ31 magnesium alloy with a pulsed current and discovered that the pulsed current decreased the dislocation density much more rapidly than annealing did. Research showed that an electric current reduced the dislocation density and promoted the plasticity of materials.23,24,25,26) However, restoration of the toughness of brittle metals using pulse-based processing has not been reported, although the effect of annealing treatment has been widely studie.27,28)

In this study, brittle A508-3 steel, a type of RPV steel, was treated by a pulsed electric current. It was found that the toughness of the brittle A508-3 steel was recovered because the dislocation defects were reduced by electropulsing. In addition, the lower activation energy of dislocation movement under the electric field and the interaction between electrons and dislocations were explained in terms of electroplastic theory and formulas derived from solid-state physics.

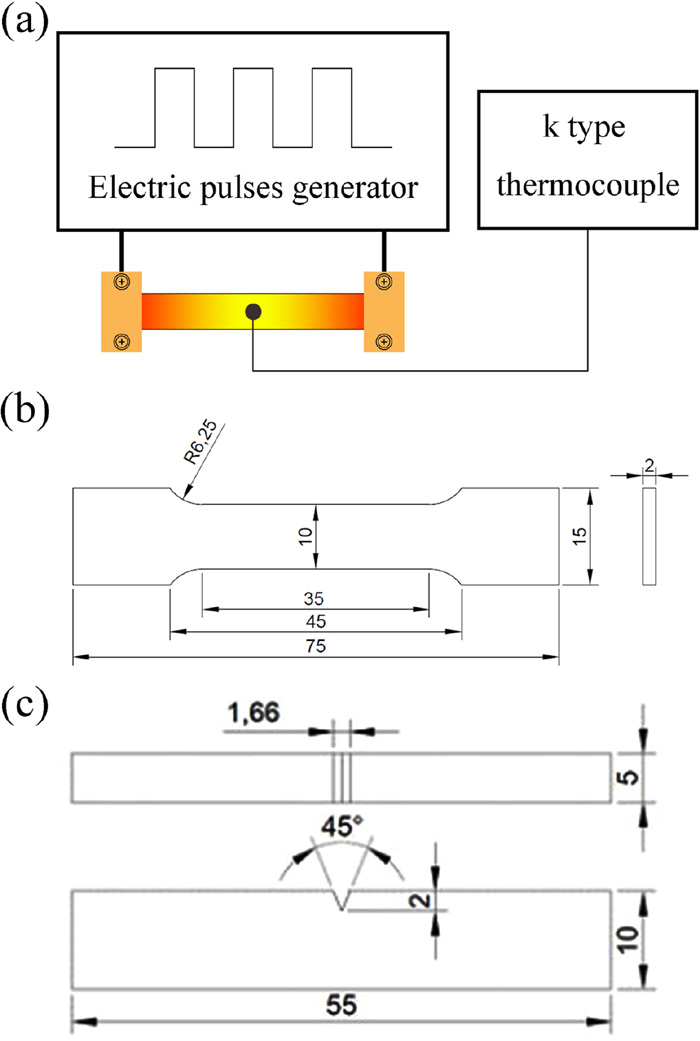

A508-3 steel containing 0.20 C, 1.30 Mn, 0.14 Cr, 0.90 Ni, and 0.039 Cu was used in this study. Since the neutron irradiation experiment requires a long time (several years) and the irradiated sample is then radioactive, the neutron irradiation experiment is replaced by aging the sample at 400°C for 1000 h to make it brittle, as reported in the study.29) The brittle sample was found to have more dislocation defects and lower toughness. It was cut to 30 mm × 10 mm × 1 mm for optical microscopy (OM), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), and X-ray diffraction (XRD) observations, tensile tests, and Charpy V-notch impact tests. The brittle A508-3 samples were treated by a pulsed electric current using the instrumental setup illustrated in Fig. 1(a), and the TEM sample was cut from the middle of the pulsed sample. The samples for the microstructural analysis and mechanical tests were treated by electric pulses for 30 min at a frequency of 500 Hz, pulse duration of 20 μs, and current density of 4 A/mm2. To characterize the microstructure, the samples were ground and mechanically polished. The polished surfaces were etched with a 10% Nital solution. Image J was used to calculate the grain size of the brittle and pulsed samples. Furthermore, XRD analysis was used to calculate the dislocation density using a Bruker D8 Advance X-ray diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 0.15406 nm) operating at 40 kV in step scanning mode at a scan speed of 0.02°/s. A scan range of 35° to 150° was chosen to cover all the diffraction peaks of bainite ferrite. To determine the strength and toughness of the A508-3 steel, a tensile test and Charpy V-notch impact test were performed. The tensile test samples were cut as shown in Fig. 1(b). According to ASTM A370 and E23, the Charpy V-notch impact samples were prepared as cuboids 55 mm × 10 mm × 5 mm in size, and the depth of the V-notch was 2 mm (Fig. 1(c)). The Boltzmann function was used to fit the impact experiment data and obtain the Charpy impact absorbed energy curve of the A508-3 steel. According to ASTM A370, the DBTT is the temperature at which the sample’s impact absorbed energy was half the upper shelf energy. The brittle samples were treated by the pulsed current, and then the tensile and impact tests were conducted. The samples were cut to 1 mm × 1 mm × 50 mm to measure the electrical resistivity.

a) Diagram of instrumental set-up for electropulsing, b) tensile test sample, c) Charpy impact sample. (Online version in color.)

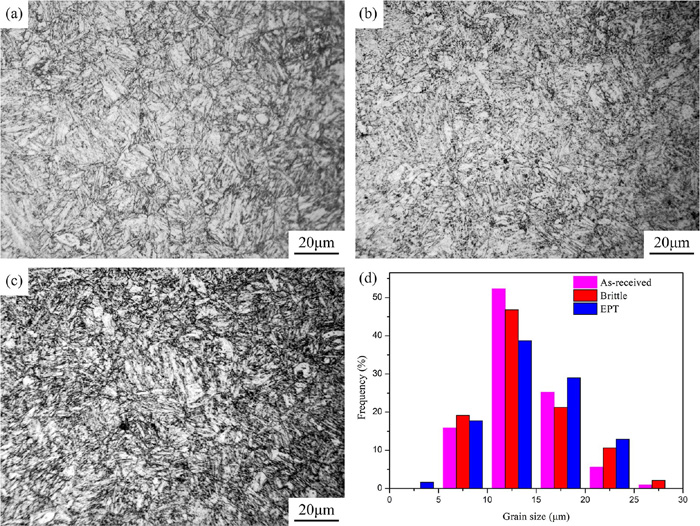

The microstructure of the as-received sample (Fig. 2(a)), brittle sample (Fig. 2(b)), and electric-pulse-treated sample (Fig. 2(c)) was lath bainite. The electric current treatment did not change the microstructure of the material. The average diameter of the original austenite grains ranged from 10 to 20 μm, as shown in Fig. 2(d), indicating that electric pulse treatment did not change the grain size of the material, which was important for the subsequent XRD analysis.

Microstructure of various samples: a) as-received, b) brittle, and c) after electric pulse treatment (500 Hz, 20 μs, 4 A/mm2, 30 min); d) grain size distributions of the samples. EPT indicates electric pulse treatment. (Online version in color.)

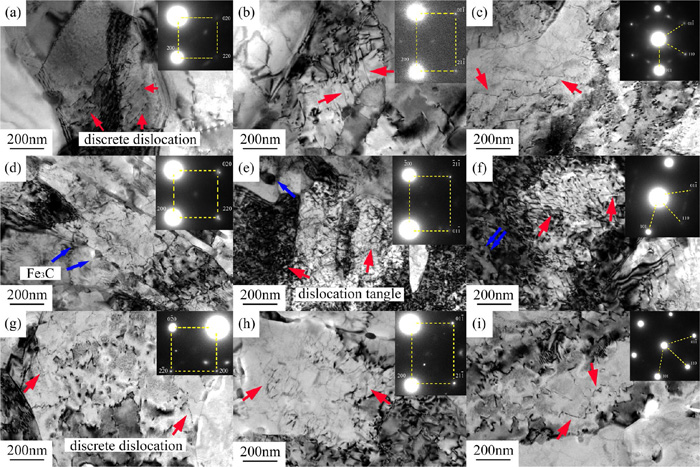

For each diffraction vector, dislocations with a Burgers vector b that fulfills the condition g·b = 0 become invisible,30) which affects the estimated dislocation density. To weaken the effect of g·b invisibility, the dislocations of the samples were observed with different diffraction vectors. TEM graphs with different diffraction vectors [B = < 001 > (Fig. 3(a)), B = < 011 > (Fig. 3(b)), and B = < 111 > (Fig. 3(c))] show that the dislocation density is low and the dislocations are discrete in the as-received sample. Figures 3(d), 3(e), and 3(f) show that the dislocation density is higher and there are many dislocation tangles in the brittle A508-3 steel. After treatment by electropulsing at 500 Hz, 20 μs, and 4 A/mm2 for 30 min, the dislocation density decreased, and the dislocation tangles were dispersed (Figs. 3(g), 3(h), and 3(i)). Thus, the dislocation defects were reduced by the pulsed electric current.

Discrete dislocations in as-received sample for different diffraction vectors: a) B = < 001 >, b) B = < 011 >, c) B = < 111 >; dislocation tangles in brittle sample for different diffraction vectors: d) B = < 001 >, e) B = < 011 >, f) B = < 111 >; discrete dislocations in the brittle sample after electric pulse treatment (500 Hz, 20 μs, 4 A/mm2, 30 min) for different diffraction vectors: g) B = < 001 >, h) B = < 011 >, i) B = < 111 >. (The red arrows indicate the dislocation defects, and the blue arrows indicate Fe3C). (Online version in color.)

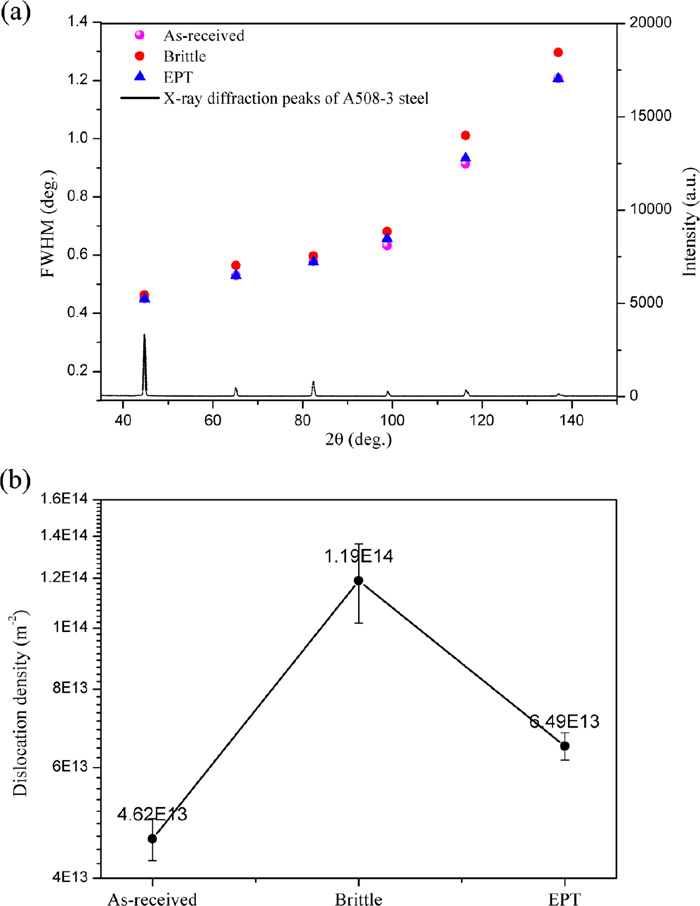

To quantify the difference in dislocation density before and after electropulsing, XRD analysis was performed. The diffraction peaks are known to become broader when the grain size changes or the lattice distortion increases in a crystal.31,32) In this study, as mentioned above, the grain size was approximately 15 ± 5 μm. Therefore, the broadening of the diffraction peaks is closely related to the increase in dislocation defects. Figure 4(a) shows the change in the full width at half-maximum (FWHM) of the samples. The FWHMs of all the diffraction peaks of the brittle A508-3 steel are clearly wider than those of the as-received sample. After treatment by electropulsing, the FWHMs of the sample dropped substantially and became essentially equal to those of the as-received sample.

a) Comparison of the FWHMs of all the peaks from 35° to 150° of the as-received, brittle, and electric-pulse-treated (500 Hz, 20 μs, 4 A/mm2, 30 min) samples. b) Dislocation density of the as-received, brittle, and electric-pulse-treated samples calculated by the MWH method. EPT indicated electric pulse treatment. (Online version in color.)

Ungár et al.33,34,35) optimized the traditional method [the Williamson–Hall (WH) method] of calculating the dislocation density using XRD and developed a more accurate method, the modified Williamson–Hall (MWH) method, as shown in Eq. (1).

| (1) |

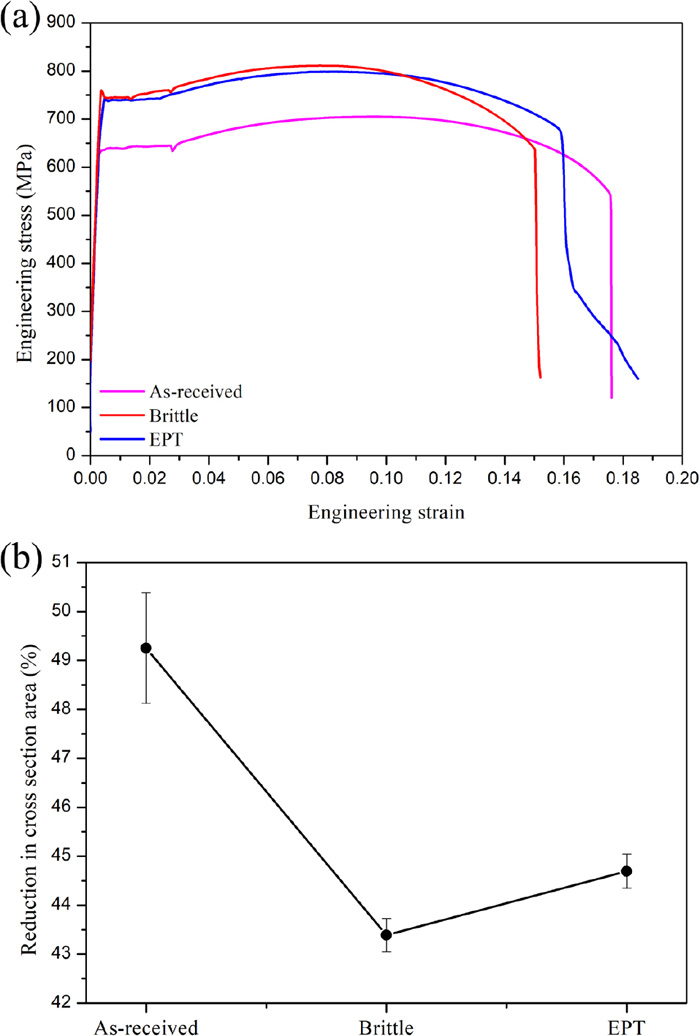

The application of multi-pulse treatment and a direct current reportedly decreases the ultimate tensile strength and yield stress of austenite–martensite transformation-induced plasticity steel.36) The pulsed electric current can also affect the tensile strength of A508-3 steel. Figure 5 presents the tensile curves of a brittle specimen obtained in pulsed and non-pulsed tensile tests. The tensile samples were treated by electric pulses (500 Hz, 20 μs, 4 A/mm2) for 30 min. The result shows that the yield stress and tensile stress of the brittle sample increased by 106 and 108 MPa, respectively, compared to those of the as-received sample, and the elongation decreased sharply, from 17.6% to 15.0%. The brittle sample had higher strength and lower plasticity than the as-received sample, demonstrating effects similar to those of neutron irradiation on RPV steel.37) Furthermore, the cross-sectional area of the as-received, brittle, and electric-pulse-treated samples after tensile testing is measured as shown in Fig. 5(b). The reduction in the cross-sectional area indicates that the plasticity was restored after electropulsing treatment. This result, along with that in Fig. 3, shows that the brittle sample has more dislocation defects. Owing to the increase in dislocation density, it was difficult for dislocations to slip; thus, hardening and strengthening occurred. After the electric pulse treatment, the dislocation defects were reduced. The elongation was improved to 16.0%, and the yield stress and tensile stress decreased slightly, indicating that the strength and plasticity were restored under the electric field.

a) Tensile curves of as-received, brittle, and electric-pulse-treated (500 Hz, 20 μs, 4 A/mm2, 30 min) samples tested at 20°C. EPT indicates electric pulse treatment. b) The reduction in cross section area of as-received, brittle and electric-pulse-treated samples after tensile testing. (Online version in color.)

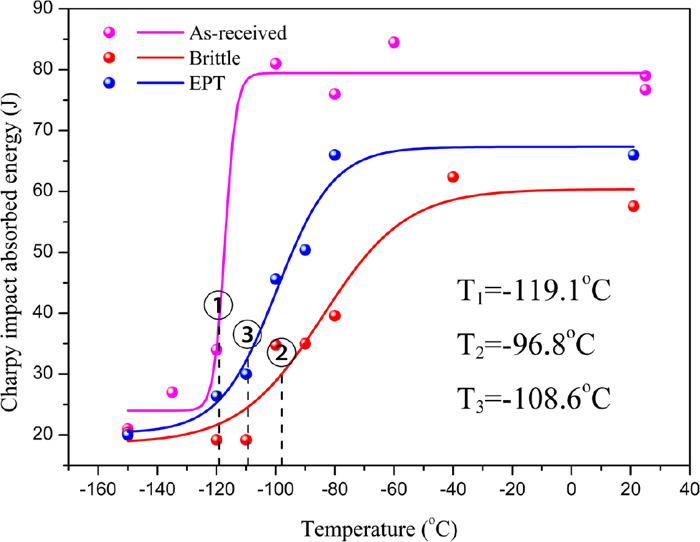

Toughness is one of the most important mechanical properties of RPV steel. After irradiation, RPV steel shows significant embrittlement.38) The Charpy V-notch impact test was performed to determine the impact toughness of the samples from –150°C to 25°C. In the Charpy impact absorbed energy curve, the upper shelf energy indicates the toughness at high temperature. As shown in Fig. 6, the upper shelf energies of the as-received, brittle, and electric-pulse-treated samples are 79.4, 60.4, and 66.0 J, respectively. This result shows that the brittle sample had lower impact resistance at room temperature. After electropulsing, the upper shelf energy was higher. According to ASTM A370, the DBTTs of the as-received, brittle, and treated samples were –119.1°C, –96.8°C and −108.6°C, respectively. The DBTT of the brittle sample was 22.3°C higher than that of the as-received sample, indicating that the toughness of the brittle sample had decreased. The electric pulse treatment reduced the DBTT by 11.8°C. Considering the decrease in dislocation density under the electric field, it is clear that the electric pulse treatment reduced the dislocation defects and restored the toughness of the brittle sample. The recovery rate of the toughness can be calculated as 11.8/22.3 × 100% = 52.9%.

Charpy impact curves of as-received, brittle, and electric-pulse-treated (500 Hz, 20 μs, 4 A/mm2, 30 min) samples from 25°C to −150°C. EPT indicates electric pulse treatment. (Online version in color.)

In agreement with the dislocation density calculated by the MWH method, the yield stress and DBTT of the brittle sample increased dramatically because the dislocation density was three times higher than that in the as-received sample. Moreover, electric pulse treatment for 30 min reduced the dislocations in the brittle sample by almost half and restored the strength and impact toughness. According to the experimental results, a reduction in the dislocation defects and an improvement in the toughness of large pressure vessels under an electric field can be expected, although there are many critical issues such as the pulse application method and the required power of the electrical source owing to the very large size of RPVs.

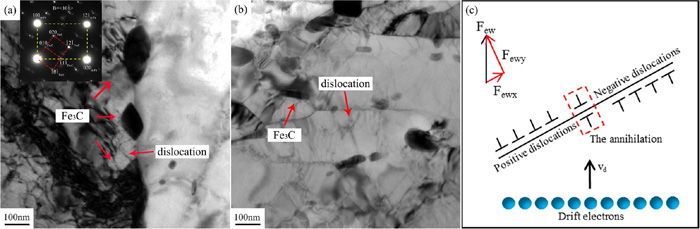

Figures 3(d), 3(e), and 3(f) show that the brittle sample has a higher dislocation density and some carbides. As shown in Fig. 7(a), Fe3C precipitates pin the dislocations and limit their movement. Therefore, the brittle sample has higher strength and lower toughness. Electric pulse treatment can reduce the pinning effect of Fe3C on the dislocations and promote dislocation movement, as shown in Fig. 7(b). There are two main reasons: (1) the electron wind force accelerates dislocation slipping and increases the probability of dislocation annihilation; (2) electric pulse treatment decreases the activation energy of dislocation movement and thus promotes dislocation depinning.

a) Pinning of dislocations by Fe3C in the brittle sample, b) depinning of dislocations by electric pulse treatment (500 Hz, 20 μs, 4 A/mm2, 30 min), c) schematic of the effect of the electron wind force on the dislocations. (Online version in color.)

A pulsed electric current can reduce the dislocation defects and change the dislocation structure. Conrad39,40,41) quantized the interaction between electrons and dislocations and obtained the following function describing the electron wind force:

| (2) |

Using quantum mechanics, Conrad derived the function

| (3) |

According to Sprecher’s investigations,42) the activation energy of dislocation movement is given by Eq. (4):

| (4) |

| (5) |

In addition, according to Ohm’s law,43) the voltage of the material is given by Eq. (6):

| (6) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

n is the number of electrons, and q is the electron charge. Then the current density is J = nqve. The electron drift velocity is

| (9) |

| (10) |

It is known that the free electrons cannot be constantly accelerated under an electric field in a material. Owing to the effect of electron scatter, the electrons will move at a stable velocity. The number of electrons that are not scattered, N(t) = N0 exp(−Pt). N0 is the number of electrons at t = 0, and P is the scatter rate of electrons per unit time. Then the electron relaxation time is

| (11) |

Assuming that the electrons have an initial velocity ve0 at t = 0, at a later time t, the velocity of electrons under the electric field is given by

| (12) |

| (13) |

| (14) |

The average electron velocity and the migration rate are clearly proportional to the relaxation time.

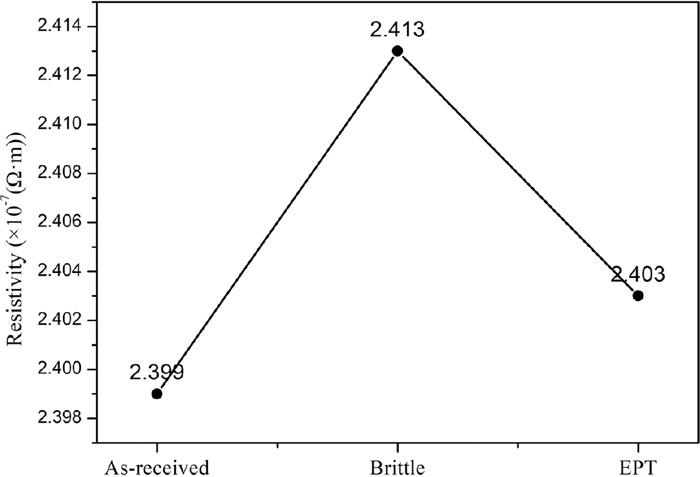

The interfacial dislocation scattering can be handled in the same way as the Coulomb scattering.44) Considering that the dislocation defects and the lattice both scatter electrons because of lattice vibration, the effect of scattering by the dislocation defects is stronger than that by the grain lattice owing to the occurrence of dislocation scattering. Then the relaxation time of materials with dislocation defects is shorter than that of materials without dislocations. As shown in Eq. (14), the migration rate of electrons is lower at the dislocations. According to Eq. (10), the conductivity of the dislocations is lower, and thus the resistivity of the dislocations is higher. In light of Joule’s law, the temperature of the dislocation defects is higher than that of the regular lattice. Therefore, the activation energy of dislocation movement is decreased, and the dislocations slip easily for other reasons in addition to the electron wind force.

To prove the theory above, the resistivity of the dislocation defects should be determined. However, it is difficult to measure the resistivity of the dislocations directly. According to Matthiessen’s rule, the total resistivity of a material with high dislocation density is bigger in the case of the same other conditions, and the total resistivity can be calculated as45)

| (15) |

As shown in Fig. 8, the brittle sample had higher resistivity than the as-received sample because it had more dislocation defects. After electric pulse treatment, the resistivity dropped dramatically, demonstrating that the electric pulse treatment reduced the dislocation defects.

Comparison of electrical resistivities of samples. EPT indicates electric pulse treatment.

In the pulsed current field, owing to the electron wind force and dislocation scattering, the activation energy of the dislocations decreased overall, improving the dislocation mobility. As they move, positive and negative dislocations may approach and annihilate each other, decreasing the dislocation density.

In summary, the effects of electropulsing on the dislocation defects and mechanical properties of A508-3 steel were investigated. The results showed that the dislocation density decreased by 45% in the brittle sample after 30 min of electric pulse treatment, and the dislocations became discrete, as they were in the undamaged sample. The strength was decreased and the plasticity and toughness were improved as a result of the reduction in dislocations. According to a calculation, the recovery rate of the DBTT was higher than 50%. Further, the interaction between the pulse current and dislocations was explained in terms of the electron wind force and the activation energy theory. This research suggests a new method for quick, energy-efficient in situ repair of brittle RPV steel (A508-3).

The work was financially supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (51874023, 51601011, U1860206), Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (FRF-TP-18-003B1), Recruitment Program of Global Experts.