2025 年 55 巻 論文ID: e007

2025 年 55 巻 論文ID: e007

Soil samples from one UNESCO World Heritage Site (Iwami Ginzan, a historic silver mine, Ohta, Shimane Prefecture) and three National Heritage Sites (Iwaki, Fukushima Prefecture) of Japan revealed 108 taxa of testate amoebae (morphospecies and morphotypes, incl. numerous “singletons”), of which cosmopolitan species, e.g., Centropyxis elongata, Euglypha rotunda, Phryganella acropodia, Plagiopyxis declivis, Trinema enchelys, and T. lineare occurred most frequently. However, some taxa such as Gibbocarina galeata, Planhoogenraadia spp., Trinema lenticularis, or Zivkovicia compressoidea have a geographically restricted distribution and/or are considered as rare. In this study, we described a new species, Centropyxis todorovi sp. nov., from Iwami Ginzan. Additionally, we suggested transferring Centropxis capucina and Centropxis pseudodeflandriana to genus Hoogenraadia and Centropxis laevigata to genus Frenopyxis.

From the historic Iwami Ginzan silver mine, soil samples were analysed for total and bio-available heavy metals (Ag, Co, Cu, Pb, and Zn). Due to the silver extraction methodology, high total concentrations of Pb and Zn had been detected. However, the bioavailable concentrations were very low. There was no relationship between the taxa numbers of testate amoebae and heavy metal concentrations.

It will be expected that further research will discover considerably more new or unrecorded testate amoebae, raising the awareness of the public, as well as of the scientific community, on these unique Heritage Sites of Japan.

Japan is known for its rich cultural heritage, and does have numerous National and World Heritage Sites (JNTO, 2025a). The Iwami Ginzan Silver Mine, a UNESCO World Heritage Site in Shimane Prefecture, Japan, is so important due to its history as a major silver producer during 1527–1923 (JNTO, 2025b). Studying soil biodiversity could reveal how centuries of mining and restoration efforts have affected the local ecosystem. In this context, biodiversity studies from three Natural Historic Sites from Fukushima Prefecture [Negishi Kanga Isekigun (a ruins group), Kabutozuka Kofun (an ancient burial mound), Shiramizu Amidado (a temple)] were included too. Generally, the investigation of soil organismic biodiversity, as those of testate amoebae, is important for the assessment and management of ecosystem health, and to raise the awareness of the scientific community, as well as of the public, on the spiritual and cultural relevance of these locations.

Japan hosts an estimated 150 to 180 known testate amoeba taxa (Shimano & Miyoshi, 2010). Research from various regions, such as from mountain forest soils (Bobrov et al., 2012), the Imperial Palace in Tokyo (Shimano et al., 2014), a fen in Central Honshu (Shimano et al., 2017), Watarase (a heavy metal contaminated floodplain; Wanner et al., 2020), and Mount Fuji (Tsyganov et al., 2022), indicate that numerous species that occur are either considered as rare or geographically restricted. It will be expected that further research in Japan will discover considerably more new or unrecorded testate amoebae.

Thus, the aim of the present study is to investigate the biodiversity and morphospecies composition of soil testate amoeba assemblages in National and World Heritage Sites of Japan.

Soil samples were taken on 16 March 2017, Iwami Ginzan in Shimane Prefecture (see Table 1, Suppl. Fig. 1), 04 March 2024, and 05 March 2024, Negishi Kanga Isekigun, Kabutozuka Kofun, and Shiramizu Amidado (see Table 1, Suppl. Figs. 2–4) in Fukushima Prefecture.

| Site | IG-1_crushing | IG-7_meadow | IG-13 lead_moss | IG-19_bamboo | IG-25_moss | IG-28_entrance | IW-NU-30 | IW-NT-31 | IW-Kofun-U32 | IW-Shir-U33 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | Ota city, Shimane Prefecture | Iwaki city, Fukushima Prefecture | ||||||||

| Iwami Ginzan | Negishi Kanga Isekigun | Kabutozuka Kofun | Shiramizu Amidado | |||||||

| Heritage | UNESCO World Heritage since 20071) | National Historic Site since 20052) | National Historic Site since 19233) | National Treasure since 19524) | ||||||

| GPS | 35°07′18″N, 132°26′53″E | 37°02′38.9″N, 140°57′30.1″E | 37°03′11.7″N, 140°56′30.7″E | 37°02′8.5″N, 140°50′13.8″E | ||||||

| Sampling date | 16 March 2017 | 05 March 2024 | 04 March 2024 | |||||||

| pH | 5.2 (KCl) | 5.8 (KCl) | 6.1 (KCl) | 5.3 (KCl) | 5.4 (KCl) | 5.2 (KCl) | 6.5 (H2O) | 6.4 (H2O) | 7.0 (H2O) | 6.7 (H2O) |

| Soil temperature (°C) | — | — | — | — | — | — | 10.5 | 9.9 | 8.9 | — |

| Sampling | corer | spatula sample | surface samples | |||||||

| depth | 0–5 cm | 0–2 cm | surface | |||||||

| Moisture (%) | 35.6 | 47.9 | 46.9 | 40.0 | — | 67.3 | 54.6 | 50.3 | 29.0 | 30.0 |

| Characteristics | n=1 (but pooled sample from 5 soil cores with d=34 mm, 0–5 cm depth; 1–23; hand samples from surface; 25–30) | n=5 (but inequal TA analysis, based on different amount of available permanent slides) | ||||||||

| note | Historic crashing place | Historic meadow/melting house | Historic silver/lead separation/moss | Historic transport near bamboo forest | Historic mine shaft entrance, liver moss, hand sample behind gate | Historic mine shaft entrance no 1, hot and humid air from inside, hand sampling behind gate | “untouched” subsite; raw humus, mixed forest, needles | “touched” subsite; raw humus, mixed forest, needles | grass on mineral soil | moss over mineral soil |

The superscript numbers refer to the following references: 1) https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1246 last access 27 Nov 2024; 2) https://bunka.nii.ac.jp/heritages/detail/163128 last access 27 Nov 2024; 3) https://bunka.nii.ac.jp/heritages/detail/190192 last access 27 Nov 2024; 4) http://www.city.iwaki.fukushima.jp/gaikokugo/english/3846/4552/4990/004520.html last access 27 Nov 2024.

As to soil sampling in 2017 (Iwami Ginzan World Heritage), governmental permission allowed the use of a standard soil corer (D=34 mm). From each site (Table 1), 5 soil samples (0–5 cm depth) were taken, covering an area of approx. 1 m2 (at two sites, sampling was possible with a spatula only, Table 1). After transfer to the laboratory on the same day, the respective 5 samples per site were combined into a composite sample followed by pH measurement (in 1 M KCl), moisture content analysis, and fixation (Roti-Histofix Eco®) for microscopy. As to soil sampling in 2024 (National Historic Sites), governmental permission ordered minimal disturbance of the respective sites. Thus, 5 small spatula samples were taken from each site (approx. 1 cm2 each, max. 2 cm depth, covering an area of 1 m2), in case of Kofun (U32), a transect from bottom to top (“surface samples”, Table 1). After transfer to the laboratory on the same day, these 5 samples per site were combined into a mixed sample with subsequent soil moisture analysis. Since only little material was available, pH measurement was conducted in situ with a pH tester (Aicevoos®). For microscopy, soil sample material was embedded in Hydro-Matrix® as permanent slides. Only these permanent slides were allowed to be transferred from Japan to Germany for further microscopical analysis on testate amoebae.

MicroscopyFor accurate determinations of testate amoeba morphospecies, permanent slides and soil suspensions were investigated under Olympus BX50 and BX51, Nikon Diaphot, Zeiss Primovert, and Axiostar microscopes. Samples were analysed quantitatively (relative abundance, n=735) and qualitatively (specimen counts). Sample size for quantitative microscopy was adjusted to the occurrence of amoeba species, i.e., soil samples from soil suspensions or permanent slides were checked as long as new species appeared (Wanner et al., 2021). Emphasis was set on the qualitative study (Wanner et al., 2024), focusing on morphospecies that occurred very rarely in the soil samples (mostly as “singletons”). Specimens were identified to species level using https://www.arcella.nl (Siemensma, 2025) and Mazei & Tsyganov (2006), as well as using the archive of all original species descriptions that were collected and made available to us by Ralf Meisterfeld (pers. comm.).

Measurement of soil pHSoil pH (one mixed sample each) was either measured in 1 M KCl solution in the laboratory (Iwami Ginzan), or measured in situ (H2O) with a soil pH tester (Aicevoos®).

Extraction of heavy metals and determination of their concentrationsHeavy metal extraction from soil samples followed Kamitani et al. (2006), considering HNO3 and CaCl2 extraction for total and available heavy metals, respectively. We analysed total concentrations and (bio-)available concentrations (i.e., not bound to soil particles) of Ag, Co, Cu, Pb, and Zn by using ICP-OES (Thermo Fisher Scientific iCAP 6000, Cambridge, UK).

Statistical analysisStatistical analysis followed Wanner et al. (2021). Graphical visualisation of data and analyses were performed with the PRIMER software (PRIMER 7 ver. 7.0.23 from PRIMER-e, Quest Research Limited). To estimate the overall number of taxa of testate amoebae in the survey area, a species accumulation curve was calculated using 9999 permutations. The number of observed taxa (Sobs) was shown, and the maximum expected number of taxa was estimated by the nonparametric Chao2 and Jackknife 2 approach. Cluster analysis was applied to measure the testate amoeba community differences (UPGMA, Bray-Curtis similarity, presence/absence transformation for taxa, log(x+1) transformation for relative abundances of taxa).

Altogether 108 taxa of testate amoebae (morphospecies and morphotypes, incl. numerous “singletons”) were detected at four heritage sites (10 sampling locations, Table 1), of which cosmopolitan species, e.g., Centropyxis elongata, Euglypha rotunda, Phryganella acropodia, Plagiopyxis declivis, Trinema enchelys, and Trinema lineare occurred most frequently. However, some taxa such as Gibbocarina galeata, Planhoogenraadia spp., Trinema lenticularis, or Zivkovicia compressoidea have a geographically restricted distribution and/or are considered as rare (Table 2). Soil pH varied from 5.2 to 6.1 (KCl method, Iwami Ginzan) and 6.4 to 7.0 (H2O method, Fukushima area). Taking into consideration the different methodologies, all soil samples revealed a mild acidic to neutral pH (Table 1).

| Japan Heritage Soil Testate Amoebae (%) | Length (µm) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IG-1_crushing | IG-7_meadow | IG-13_lead_moss | IG-19_bamboo | IG-25_moss | IG-28_entrance | IW-NU-30 | IW-NT-31 | IW-Kofun-U32 | IW-Shir-U33 | ||

| cf. Arcella | 70–100 | 3.33 | 3.28 | 1.34 | 1.45 | 1.61 | |||||

| Arcella cf. rotunda/hemisphaerica | 48 | 0.45 | |||||||||

| Arcella sp. | 54–75 | 0.45 | 1.01 | ||||||||

| cf. Argynnia (without rough mouth) | 114–125 | 1.01 | 0.69 | ||||||||

| Argynnia dentistoma | 105–127 | 0.45 | 1.45 | 1.01 | |||||||

| Assulina muscorum | 46 | 1.01 | |||||||||

| Assulina cf. muscorum denticulata | 63 | 0.45 | |||||||||

| Awerintzewia cyclostoma | 146–170 | 0.45 | 1.45 | ||||||||

| Centropyxis aculeata var. grandis | 107–140 | 5.80 | |||||||||

| Centropyxis aerophila complex | 51–98 | 3.33 | 1.64 | 1.79 | 2.90 | 4.04 | 0.69 | 4.76 | |||

| Centropyxis capucina | 65–84 | 0.45 | 1.45 | ||||||||

| Centropyxis cavitastoma | 50–83 | 6.67 | 4.46 | 5.00 | 1.45 | 1.01 | 3.47 | 6.45 | 4.76 | ||

| cf. Centropyxis | 205 | 1.45 | |||||||||

| Centropyxis constricta | 83–121 | 4.92 | 8.04 | 5.80 | 1.01 | 1.39 | 1.61 | ||||

| Centropyxis elongata | 46–86 | 30.00 | 3.28 | 4.91 | 5.00 | 1.45 | 8.08 | 0.69 | 1.61 | 4.76 | 5.88 |

| Centropyxis cf. gauthieri | 72–79 | 0.45 | 1.01 | ||||||||

| Centropyxis minuta | 41 | 0.45 | |||||||||

| Centropyxis oblonga | 105–140 | 1.45 | 1.01 | 5.88 | |||||||

| Centropyxis orbicularis | 86–126 | 0.45 | 1.45 | 1.01 | 0.69 | ||||||

| Centropyxis pseudodeflandriana | 75 | 1.45 | |||||||||

| Centropyxis sacciformis | 67–84 | 1.01 | 0.69 | 1.61 | |||||||

| Centropyxis sphagnicola | 45–68 | 3.33 | 1.64 | 4.46 | 5.00 | 2.90 | 1.01 | 4.17 | 9.68 | 14.29 | 5.88 |

| Centropyxis spinosa | 106–137 | 1.45 | |||||||||

| Centropyxis cf. stenodeflandriana | 80 | 0.69 | |||||||||

| Centropyxis cf. sylvatica | 73–83 | 0.89 | 1.45 | 3.23 | |||||||

| Centropyxis todorovi | 72–94 | 6.56 | 5.36 | 1.01 | |||||||

| Corythion dubium | 37 | 1.45 | |||||||||

| cf. Cryptodifflugia | 1.61 | ||||||||||

| Cryptodifflugia operculata | 16 | 1.01 | |||||||||

| Cyclopyxis (eurystoma) parvula | 30–46 | 0.45 | 4.04 | 1.39 | 3.23 | 4.76 | |||||

| Cyclopyxis cf. ambigua | 53–57 | 0.45 | 1.61 | ||||||||

| Cyclopyxis arcelloides | 93 | 0.45 | |||||||||

| cf. Cyclopyxis | 56 | 1.45 | 1.01 | 2.08 | |||||||

| Cyclopyxis intermedia | 188 | 5.00 | |||||||||

| Cyclopyxis kahli | 66–110 | 1.64 | 2.23 | 1.45 | 1.01 | 1.61 | 4.76 | ||||

| Cyclopyxis cf. kahli cyclostoma | 73–90 | 1.79 | 5.88 | ||||||||

| Difflugia cf. bacillifera | 160 | 0.45 | |||||||||

| Difflugia glans | 54–64 | 0.45 | |||||||||

| Difflugia (Heleopera) lucida | 47–72 | 0.45 | 3.03 | 2.08 | |||||||

| Difflugia cf. manicata | 65–77 | 0.45 | 12.12 | ||||||||

| Difflugia masaruzzii | 50–72 | 3.57 | 1.45 | 1.01 | |||||||

| Difflugia nana | 16–20 | 2.02 | 1.39 | 1.61 | |||||||

| Difflugia cf. oblonga | 103 | 1.45 | |||||||||

| Difflugia pristis | 46–49 | 0.45 | 1.01 | ||||||||

| Difflugia sp. 1 | 145 | 1.45 | |||||||||

| Difflugia sp. 2 | 50–51 | 1.64 | 0.45 | 1.45 | 0.69 | ||||||

| Euglypha cf. bryophila | 46–50 | 1.01 | |||||||||

| Euglypha cf. compressa | 1.39 | 11.76 | |||||||||

| Euglypha cristata | 53–55 | 0.45 | 1.01 | ||||||||

| Euglypha filifera | 52 | 0.45 | |||||||||

| Euglypha cf. laevis | 22–23 | 3.33 | 1.01 | ||||||||

| Euglypha rotunda | 30–57 | 6.67 | 11.48 | 3.57 | 5.00 | 2.90 | 1.01 | 8.33 | 4.84 | 4.76 | 23.53 |

| Euglypha strigosa | 62–65 | 1.01 | 1.39 | ||||||||

| Euglypha tuberculata | 55–83 | 0.45 | 1.45 | 1.01 | 5.88 | ||||||

| Galeripora sp. 1 | 51 | 0.45 | |||||||||

| Galeripora sp. 2 | 85–90 | 1.45 | 1.01 | ||||||||

| Gibbocarina galeata | 190–202 | 0.45 | 13.04 | 0.69 | 1.61 | ||||||

| Heleopera petricola | 60–115 | 0.45 | 1.01 | 0.69 | |||||||

| Heleopera sylvatica | 61–84 | 0.89 | 1.45 | 1.01 | 1.39 | ||||||

| Hyalosphenia subflava | 72–80 | 0.69 | 6.45 | ||||||||

| Ichthyosquama loricaria | 110–133 | 1.45 | |||||||||

| Lagenodifflugia bryophila | 100–165 | 0.45 | 1.45 | ||||||||

| Lesquereusia modesta | 110 | 0.45 | |||||||||

| Longinebela cf. penardiana | 85 | 1.01 | |||||||||

| Nebela collaris-bohemica complex | 100–110 | 1.45 | 1.01 | 0.69 | 3.23 | ||||||

| Nebela tincta complex | 101–111 | 0.45 | 1.01 | ||||||||

| Padaungiella lageniformis | 110–115 | 1.45 | 1.01 | ||||||||

| Phryganella acropodia | 29–45 | 6.67 | 6.56 | 2.23 | 5.00 | 1.45 | 4.04 | 13.89 | 20.97 | 4.76 | 5.88 |

| Phryganella hemisphaerica | 69–74 | 0.45 | 1.01 | ||||||||

| Phryganella paradoxa | 32–37 | 1.45 | |||||||||

| Plagiopyxis cf. angularis | 53–66 | 0.45 | 1.45 | ||||||||

| Plagiopyxis barrosi | 57 | 0.45 | |||||||||

| Plagiopyxis callida | 89–130 | 0.45 | 5.00 | 1.45 | 2.78 | ||||||

| Plagiopyxis declivis | 50–84 | 16.67 | 16.39 | 16.96 | 5.00 | 1.45 | 5.05 | 8.33 | 11.29 | 14.29 | 5.88 |

| Plagiopyxis declivis big type | 88 | 1.01 | |||||||||

| Plagiopyxis declivis eustoma | 53 | 0.45 | |||||||||

| Plagiopyxis declivis oblonga | 62 | 1.01 | |||||||||

| Plagiopyxis intermedia | 50–61 | 1.79 | 5.00 | 2.02 | |||||||

| Plagiopyxis cf. minuta | 40–52 | 0.45 | 5.00 | 1.45 | 14.29 | ||||||

| Plagiopyxis oblonga | 55–95 | 3.33 | 8.20 | 1.79 | 5.00 | 2.90 | |||||

| Plagiopyxis sp. | 48–60 | 3.33 | 0.45 | 1.45 | 1.01 | 1.61 | |||||

| Planhoogenraadia cf. alta | 120 | 0.45 | |||||||||

| Planhoogenraadia cf. media | 65–85 | 1.64 | 1.79 | 1.45 | 1.01 | ||||||

| Porosia bigibbosa | 143 | 1.01 | |||||||||

| Pseudawerintzewia sp. | 63–68 | 0.45 | |||||||||

| Pseudodifflugia sp. | 32 | 1.01 | |||||||||

| cf. Pseudonebela rubescens | 65 | 0.45 | |||||||||

| Pyxidicula cf. ornata | 70 | 0.45 | |||||||||

| Pyxidicula cymbalum | 60 | 0.45 | |||||||||

| Quadrulella symmetrica | 71 | 1.01 | |||||||||

| Schoenbornia humicola | 26–31 | 5.00 | 1.45 | 2.02 | |||||||

| Schoenbornia viscicula | 15–24 | 3.33 | 1.64 | 0.45 | 1.45 | 1.01 | |||||

| cf. Schwabia (Difflugia) stoutii | 50–53 | 0.45 | |||||||||

| Sphenoderia cf. lenta | 37–42 | 1.01 | |||||||||

| Tracheleuglypha acolla | 35–42 | 10.00 | 2.08 | 4.76 | |||||||

| Tracheleuglypha dentata | 42–55 | 2.68 | 5.00 | 1.45 | 1.01 | 2.08 | |||||

| Trachelocorythion pulchellum | 25–39 | 1.45 | 1.01 | ||||||||

| Trigonopyxis arcula | 85 | 4.84 | |||||||||

| Trigonopyxis microstoma | 81 | 1.01 | |||||||||

| Trinema complanatum | 33–45 | 1.64 | 0.45 | 5.00 | 1.45 | 1.01 | 9.72 | 4.84 | 4.76 | ||

| Trinema enchelys | 42–87 | 3.33 | 19.67 | 4.02 | 5.00 | 1.45 | 2.02 | 15.28 | 1.61 | 9.52 | 5.88 |

| Trinema galeata | 40–45 | 0.45 | 1.45 | 1.01 | |||||||

| Trinema grandis | 100–121 | 0.45 | 1.45 | 2.02 | |||||||

| Trinema lenticularis | 34–41 | 3.33 | 0.45 | 5.00 | 1.01 | ||||||

| Trinema lineare | 22–40 | 3.33 | 8.20 | 5.36 | 5.00 | 1.45 | 1.01 | 9.03 | 3.23 | 4.76 | 17.65 |

| Trinema sp. | 17 | 1.01 | |||||||||

| Valkanovia elegans | 40 | 5.00 | 1.01 | 0.69 | |||||||

| Zivkovicia compressoidea | 188 | 1.45 | |||||||||

| Taxa (total=108) | 15 | 17 | 66 | 19 | 51 | 61 | 31 | 23 | 14 | 11 |

Empty (dead) and full (living+encysted) shells were combined. We suggest to transfer C. capucina and C. pseudodeflandriana to genus Hoogenraadia (see text).

From the UNESCO World Heritage Site Iwami Ginzan, six different sampling locations were chosen, reflecting different characteristics from this historic silver mine (Table 1). Due to its history as a silver mine operating for a long time (396 yr), the heavy metal content of the soil was analysed (Table 3). The historic silver extraction (introduced from Korea in 1533) was based on a cupellation method (“haifuki-ho”) (JNTO, 2025), thus high total concentrations of Pb and Zn were detected. However, the (bio-)available concentrations (i.e., not bound to soil particles) were very low (Table 3). Any relationship to the number of testate amoeba taxa was not visible (Tables 2 and 3).

| Site | IG-1 | IG-7 | IG-13 | IG-19 | IG-25 | IG-28 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moisture (%) | 35.6 | 47.9 | 46.9 | 40 | — | 67.3 |

| pH(KCl) | 5.2 | 5.8 | 6.1 | 5.3 | 5.4 | 5.2 |

| TAtaxa | 15 | 17 | 66 | 19 | 49 | 61 |

| Agtotal (mg kg−1) | 88 | 4 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 5 |

| Cototal (mg kg−1) | 13 | 9 | 7 | 11 | 7 | 5 |

| Cutotal (mg kg−1) | 342 | 41 | 32 | 26 | 37 | 71 |

| Pbtotal (mg kg−1) | 4762 | 294 | 228 | 141 | 525 | 1969 |

| Zntotal (mg kg−1) | 1660 | 450 | 344 | 308 | 1308 | 1102 |

| Agavail (µg kg−1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Coavail (µg kg−1) | 18 | 18 | 15 | 223 | 71 | 0 |

| Cuavail (µg kg−1) | 115 | 45 | 72 | 77 | 172 | 0 |

| Pbavail (µg kg−1) | 99 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Znavail (µg kg−1) | 43891 | 1395 | 477 | 10241 | 38564 | 0 |

Total amount by HNO3 extraction, available amount by CaCl2 extraction.

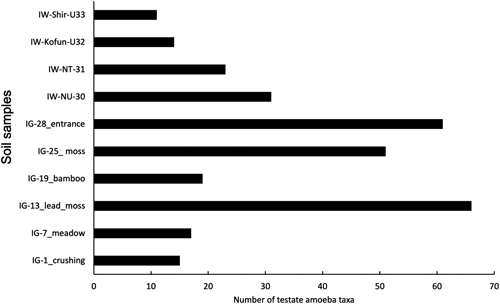

Most of the total 108 testate amoebae taxa were found at Iwami Ginzan site IG-13 (former lead separation location with mosses; 66 taxa) and IG-28 (historic mine shaft entrance, hot and humid, 61 taxa). Considerably less amoeba taxa were found in the former crushing place (IG-1, 15 taxa), meadow (IG-7, 17 taxa), and bamboo forest (IG-19, 19 taxa) (Fig. 2).

As to the three National Historic Sites from Fukushima Prefecture (Iwaki), available permanent slides revealed 42 amoebae taxa in total, most of them (38 taxa) from Negishi Kanga Isekigun. Here, a small “untouched” area (NU, fenced shrine area) and adjacent “touched” area (NT, unfenced mixed forest) were investigated. The “untouched” area harboured 31 taxa, while in the “touched” area, 23 testate amoeba taxa were found (Fig. 2, Table 2). Cluster analysis of the ten samples taken from Iwami Ginzan and Fukushima Prefecture sorted by location and vegetation cover, in which IG-28, IG-25, and IG-13, with their high numbers of taxa, were separated clearly from the other sites (Figs. 3 and 4). Furthermore, the two sites from Negishi Kanga Isekigun (IW-NU-30, IW-NT-31) clustered together (Figs. 3, 4).

A proper sampling size was confirmed by the species-accumulation curve shown in Fig. 1. The sampling effect appears high, because the Chao 2 species accumulation curve reached its asymptote, while the Jackknife 2 curve was close to stabilisation (Fig. 1). However, since different sampling locations were merged and because of the difficult sampling conditions in the Fukushima area resulting in only a few permanent slides for observation, this statement may be applied only for the Iwami Ginzan site.

As to the environmental impact regarding heavy metals, this study shows the importance of differentiating between total and available heavy metal concentrations. At older sites, the binding of heavy metals to the soil increased over time, resulting in decreased availability of heavy metals in the soil pore water (Kamitani et al., 2006; Wanner et al., 2020). Wanner et al. (2020) demonstrated that, e.g., densities of C. kahli cyclostoma, Centropyxis spp., and Trinema complanatum were negatively correlated to concentrations of available heavy metals, resulting also in a decline in protozoic silicon pools. However, the concentrations of (bio-)available heavy metals in this study were very low, and we considered only the number of testate amoebae taxa, not densities, since the focus of this work was on amoebal species composition.

The original objective was to compare multiple “untouched” (fenced) heritage areas with adjacent “touched” (unfenced) sites. However, due to challenging sampling conditions, only a limited number of samples were obtained. While the resulting statistical analyses yielded no unexpected or highly significant findings, we consider the data valuable. Even seemingly self-evident patterns warrant documentation, as they may provide valuable data for future meta-analyses.

Morphological observationsIn this study, several species were identified that had previously been observed only sporadically. These findings provide new morphological data of potential taxonomic significance, including the description of a new species within the genus Centropyxis and three new combinations. The identification of some shells was challenging due to damage or compression. This was particularly problematic for identifying Arcella and Galeripora shells, as observing them in a lateral view is crucial. Additionally, many shells were attached to debris, making them difficult to manipulate, especially when mounted in wet preparations.

Observations on Centropyxis aculeata var. grandis Deflandre, 1929 (Figs. 5A and B)In the Japanese material, four shells were present that measured 107–140 µm in diameter excluding spines, and bore a striking resemblance to the illustration of C. aculeata var. grandis (Fig. 93 in Deflandre’s monograph; Deflandre, 1929). The shells were nearly circular, with a regular distribution of a few short spines, a relatively small amount of xenosomes and a relatively small aperture. Notably, the ventral side of these shells was entirely free of xenosomes, and a clear boundary was visible between the ventral side and the rest of the shell (Fig. 5B). A similar phenomenon was previously reported by Dekhtyar (1998) for C. bryophilus (her Fig. 6) and by Todorov & Bankov (2019) for C. spinosa (their Figs. 59B–E, H). It remains unclear whether this is a species-distinguishing characteristic, and if C. aculeata grandis is a species or subspecies, but it certainly warrants further attention in future morphological studies.

This species can be confused with C. plagiostoma Bonnet & Thomas, 1955. However, Bonnet & Thomas (1955) described it as having a flat ventral area and a slight invagination of the aperture, whereas C. cavitastoma is characterised by a broad inward curvature of the ventral side (Bobrov, 2020). Drawings by Bonnet & Thomas (1955, Fig. 19) and Bonnet (1961, Pl. 1b; 1964, Fig. 20; 1975b, Fig. 32) of C. plagiostoma clearly illustrate this feature: a slight invagination compared to the higher and much broader invagination characteristic of C. cavitastoma. Therefore, we consider the Japanese specimens identical to C. cavitastoma. We agree with Bobrov (2020) that the description and illustrations of C. plagiostoma by Foissner & Korganova (1995) correspond to C. cavitastoma. It is highly likely that several earlier observations of C. plagiostoma also refer to C. cavitastoma. The dimensions of the Japanese specimens of C. cavitastoma are 52–83 µm, which is smaller than those reported by Bobrov (2020): 100–123 µm. However, a population found in dry moss near Olympia, Greece (Siemensma, 2025, unpublished) measured 82–110 µm. Foissner & Korganova (1995) reported two clearly distinct size classes for this species: 80–120 µm and 50–70 µm in diameter, respectively. The latter corresponds well to the Japanese population (52–83 µm). These observations support earlier findings from detailed morphometric studies, which indicate that metrical scale characters are highly variable (e.g., Schönborn, 1992; Foissner & Korganova, 1995).

Observations on bridged Centropyxis species (Fig. 6)In samples from Japan, several shells of a Centropyxis species with three internal bridges were observed. These shells were slightly oval to nearly circular in dorsal view, with an eccentrically positioned round or occasionally drop-shaped aperture. The aperture is surrounded by an internal rim from which three band-like bridges extend to the opposite inner side of the dorsal surface. In dorsal view, these three bridges or struts form a triangular structure, with the apex pointing forward and the base aligned with the midline of the aperture (Figs. 6A, B). In lateral view, the shell height is approximately half its diameter, tapering sharply from the posterior toward the anterior (Fig. 6C).

Similar shells have been reported and/or illustrated by various authors (Schönborn et al., 1983; Chattopadhyay & Das, 2003; Purushothaman & Bindu, 2015; Todorov & Bankov, 2019; Farooqui et al., 2020). Schönborn et al. (1983) provide a detailed description, consistently noting the presence of three internal struts. Although not explicitly mentioned, these struts are consistently visible in illustrations provided by these authors (Schönborn et al., 1983, Figs. 1a–f; Purushothaman & Bindu, 2015, Figs. 1 and 2; Todorov & Bankov, 2019, Fig. 55; Farooqui et al., 2020, Pl. II and Figs. 4–20). Chattopadhyay & Das (2003) describe this species as “having apertural bridges”, but do not depict them in their Figs. 59–61. Todorov & Bankov (2019) describe the shell as “considerably compressed towards the aperture,” while Schönborn et al. (1983) refer to it as wedge-shaped (“keilförmig”).

Schönborn et al. (1983), Chattopadhyay & Das (2003), Todorov & Bankov (2019), and Farooqui et al. (2020) identify their species as C. laevigata, while Purushothaman & Bindu (2015) attribute theirs as C. delicatula Penard, 1902. However, the original description of C. laevigata Penard, 1890, differs significantly from the shells described by these authors. Penard (1890) described a high dome that is barely compressed at the anterior (“un dôme assez élevé et à peine comprimé en avant”), with measurements of 120–150 µm in diameter and 80–120 µm in height. The ventral area features a deep, inward-invaginated, eccentrically located round aperture, connected to the opposite dorsal wall by a single broad chitinous band covered with thick amorphous scales (“une large bride foncée couverte d’écailles morphes épaisses”). Penard’s drawings clearly illustrate these features (Penard, 1890, 1902). The single band or bridge is a defining characteristic of the genus Frenopyxis Bobrov & Mazei, 2020, and we propose transferring C. laevigata to this genus (see taxonomic account).

The discrepancies between previously observed specimens and Penard’s original description indicate that the shells attributed to C. laevigata by these authors do not belong to that species. However, the reported shells exhibit consistent morphological traits, leading us to describe them as a new species, Centropyxis todorovi sp. nov. (see taxonomic account). Schönborn et al. (1983) had already noted the need for a more precise description of this species, which they had identified as C. laevigata.

Centropyxis delicatula Penard, 1902, is another species with internal bridges. Penard (1902) described it as very small, with a diameter of 35–48 µm. This species, characterised by a predominantly organic shell, is relatively flat and has an inward-facing construction around the aperture, featuring four to five bridges connecting the ventral side to the opposite inner dorsal wall. At the posterior side of the aperture, adjacent to the fundus, there are always two and sometimes three bridges, while at the anterior side, there are consistently two shorter bridges. The posterior bridges converge at the top, forming a rounded window. Occasionally, Penard (1902) observed one or two spines at the rear of the shell. The internal framework resembles that of Centropyxis lapponica (Łuców et al., 2025, Fig. 7f).

Micrographs by Purushothaman & Bindu (2015), attributed to C. delicatula, show three bridges arranged in a triangular position. These shells do not match the original description of C. delicatula but instead resemble C. todorovi sp. nov.

It is likely that C. laevigata and C. delicatula have been misattributed to other species in the past. Tripathi et al. (2017) published a micrograph of a shell with bridges and spines labelled as C. laevigata (their Fig. 8h). However, the presence of spines and the number of bridges fall outside the diagnosis of C. laevigata. Similarly, their Fig. 8g depicts a shell with four bridges. Chattopadhyay & Das (2003) reported C. laevigata and noted the presence of bridges but provided drawings without any indication of these structures, making it difficult to assess their observations. The same issue applies to the drawings published by Golemansky (1966) as C. laevigata.

Taxonomic position of bridged Centropyxis speciesThe position and number of bridges in a Centropyxis shell could serve as valuable characteristics for distinguishing and describing species more accurately. Lahr et al. (2008) demonstrated through their description and SEM images that the species they identified as C. aculeata had four support points, externally visible as small indentations under SEM. Siemensma (2025) discovered a large population of C. aculeata (or a subspecies thereof) in a sample from the Odenwald region, Germany. All specimens exhibited two frontal struts attached to the anterior part of the inner dorsal region. In shells that we, outside the scope of this study, consider belonging to C. spinosa, we consistently observe two pillars on each side of the aperture. This characteristic is also evident in the images published by Todorov & Bankov (2019) under the name C. spinosa.

Dekhtyar (2009) proposed the genus Armipyxis to accommodate Centropyxis species with bridges, designating Armipyxis discoides as the type species. This was an elegant attempt to introduce some order into the large assemblage of species currently classified under the genus Centropyxis. However, the type species of the genus Centropyxis is C. aculeata (Ehrenberg, 1830). Although bridges were not mentioned in the original description of this species, it is highly likely that they were present but could not be observed with the techniques available at the time, as Leidy (1879) had noted. Leidy (1879) described and illustrated C. aculeata specimens in which these bridges are clearly visible. It is probable that Leidy also included under C. aculeata certain species that had not yet been formally described, such as C. spinosa, C. lapponica and C. discoides. Penard (1902) also referred to internal bridges in his description of C. aculeata and Deflandre (1929), in his monograph, similarly indicated that partitions might be present in C. aculeata.

Based on the aforementioned observations, as well as more recent findings by Lahr et al. (2008) and Siemensma (2025), it can be concluded that C. aculeata possesses internal bridges. Consequently, the validity of the genus Armipyxis is undermined, as C. aculeata is the type species of the genus Centropyxis and therefore cannot be transferred to Armipyxis.

Observations on Centropyxis sacciformis Hoogenraad & De Groot, 1946 (Figs. 7A, B)The shells were oval-shaped with a strongly oblique aperture (Fig. 7B). The dimensions of the Japanese specimens are slightly smaller (67–84 µm in length and 46–47 µm in width) than those reported by Hoogenraad & De Groot (1946), which range from 70–87 µm in length and 53–67 µm in width.

This species was described by Hoogenraad & De Groot (1946) from both recent and fossil material collected on the Indonesian island of Java. The authors characterised it as a species that can sometimes be quite abundant but exhibits variability: at times, it presents a nearly identical form, whereas in other instances, it shows a wide range of variation, making it difficult to distinguish from closely related forms. We previously identified this species in Bhutan (Wanner et al., 2024) and now in Japan, where Shimano et al. (2014) also reported C. sacciformis at the Imperial Palace.

Observations on Centropyxis capucina Bonnet, 1975a (Figs. 7C–H)The morphology of the observed shells closely matched the descriptions provided by both Bonnet (1975a) and Coûteaux (1976), who studied material from the same area. Observations of multiple shells revealed that their optical appearance can vary considerably depending on the angle of observation, particularly concerning the depth and the angle between the visor and the body (Figs. 7D, F–H). The ventral area may range from slightly convex to distinctly convex. The shells were 65–84 µm long (mean 76.2 µm), 38–49 µm wide (mean 43.6 µm) and 36–44 µm thick (mean 40.0 µm, n=8).

These measurements correspond to those reported by Bonnet (1975a) and Coûteaux (1976). Although Coûteaux (1976) does not provide any description of C. capucina, the visor of her drawn specimen is considerably larger than that depicted by Bonnet (1975a). Based on the convex ventral area and the angled visor, Centropyxis capucina appears to be closely related to species within the genus Hoogenraadia. Therefore, we propose transferring this species to the genus Hoogenraadia.

Observations on Centropyxis pseudodeflandriana Bonnet & Gomez-Sanchez, 1984 (Figs. 7I–L)We found only one specimen of C. pseudodeflandriana, 75.5 µm long and 45.7 µm wide, but the resemblance to the original description and illustrations was clear: a low visor, with a dorsal lip forming an elliptical arc, the ventral lip slightly folded inward and, in dorsal or lateral view, a distinct suture is visible between the body and the visor (Fig. 7K).

In their illustrations, Bonnet & Gomez-Sanchez (1984) show that the shape and position of the visor can vary, from open (their Figs. 1–3) to a cryptostome (their Fig. 4). This species also strongly resembles Hoogenraadia ovata Bonnet, 1974. Therefore, we consider it justified to classify Centropyxis pseudodeflandriana within the genus Hoogenraadia.

Taxonomic accountZooBank registration number of the present work:

urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:D0680C68-F266-4F34-88EE-4FB53EA0AA81

ZooBank registration number of the new species:

urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:5273B8A6-1C18-4F37-A2B0-08F6DEDBC268

Examined material: 7 specimens (including the holotype and the paratype); all materials are taken from IG-13 (the former lead separation location with mosses), as listed in Table 1.

Diagnosis. In the ventral view, the shell is broadly oval to circular. In the lateral view, the shell height is less than half the shell diameter and is strongly compressed towards the frontal area. The aperture is eccentrically located, invaginated, and usually equipped with three bridles or struts that connect the invagination to the ceiling of the shell. These bridles form the vertices of an isosceles triangle, with the apex pointing towards the frontal area of the shell. The base of this triangle roughly aligns with the midline of the aperture. The organic cement of the ventral area is smooth and lacks embedded xenosomes, whereas the dorsal area contains mineral particles, which increase in size towards the posterior part.

Morphometry. Shell diameter 72–82×78–94 µm (n=7), height 35–41 µm (n=2), aperture 21.1 µm×23.3 µm (n=5)

Etymology. The species is dedicated to Dr. Milcho Todorov for his excellent work on the morphology and morphometry of testate amoebae.

Type specimen. The holotype [specimen number TNS AL-66028sa] and a paratype [specimen number TNS AL-66028sb] were mounted in Hydro-Matrix® on each glass slide and deposited in the collection of Department of Botany, National Museum of Nature and Science, Tokyo (TNS).

Type figure. Fig. 6C.

Type locality. Iwami Ginzan, Japan. GPS 35°07′18″N 132°26′53″E.

Description of the Japanese specimens. The shells were ellipsoid, rarely nearly circular, flattened, with the frontal region slightly more pronounced than the posterior, resulting in a wedge-shaped side view (Fig. 6C). Smaller shells were relatively higher than larger shells. The pseudostome was regularly to irregularly ellipsoid and always distinctly off-centre, creating a narrower frontal and a broader posterior shell section. The ventral side sloped steeply dorsally towards the aperture in the frontal region, whereas in the posterior region, the slope was moderate. Due to this steep decline in the frontal region, the pseudostome rim appeared thickened when viewed from above. The aperture is surrounded by an internal organic rim from which three band-like pillars connect to the opposite inner side of the dorsal surface. These three pillars or bridges form, in a dorsal view, a triangle with the apex pointing forward and the base formed by the midline of the aperture. In dorsal and lateral views, the shells were distinctly pitted at the attachment points of these three pillars (Fig. 6F). Young shells were light brown, while older ones were dark brown, sparsely to densely covered with thin, colourless mineral particles, which are usually less dense ventrally than dorsally. Often, the platelets are so thin that the underlying shell structure remained visible under light microscopy. The shells were relatively soft, flexible, and exhibited a hexagonal to polygonal pattern of building blocks. These blocks were approximately 0.5 µm in size and could be observed under strong magnification with a light microscope. In older shells, these ridges may become indistinct.

Differential diagnosis. Centropyxis todorovi sp. nov. can be distinguished from all known bridged Centropyxis species by the presence of three internal bridges arranged in the form of a triangle with the apex pointing forward.

Distribution. Japan (this study); Germany (near Jena: Schönborn et al., 1983; Odenwald, Siemensma, 2025); Austria (Schönborn et al., 1983); India (Chattopadhyay & Das, 2003; Farooqui et al., 2020; Purushothaman & Bindu, 2015); Bulgaria (Todorov & Bankov, 2019).

New combinations:This study was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS, fellowship ID S16738 and S23134, MW) and the research funds of the Asahi Glass Foundation for SS. We thank the Ohta City and Iwaki City administrations for their permission. The laboratory team of the Dept. Soil Protection and Recultivation, BTU Cottbus-Senftenberg, Germany, kindly conducted the heavy metal analyses.

The following supplementary information can be downloaded at: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30353653.v1, Supplementary Figure 1: Iwami Ginzan in Shimane Prefecture. Supplementary Figure 2: Shiramizu Amidado in Fukushima Prefecture. Supplementary Figure 3: Kabutozuka Kofun in Fukushima Prefecture. Supplementary Figure 4: Negishi Kanga Isekigun in Fukushima Prefecture.