2024 Volume 49 Issue 4 Pages 232-242

2024 Volume 49 Issue 4 Pages 232-242

The Cry1Fa insecticidal protein from Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) was expressed on the surface of Bacillus subtilis (Bs) spores to create transgenic Bs spores referred to as Spore-Cry1Fa. Cry1Fa, along with its leader sequence, was connected to the carboxyl end of a Bs spore outercoat protein, CotC, through a flexible linker. The Arg-27 residue of the Cry1Fa protein was mutated to Leu to prevent detachment from the spores due to protease digestion. The expression of the Cry protein on the Bs spores was confirmed by fluorescence microscopy using an anti-Cry1Fa antibody. The Cry protein, tightly anchored to the spore surface, appeared to be functional in terms of receptor binding. Spore-Cry1Fa bound to Sf9 cells expressing Spodoptera frugiperda (Sf) ABCC2 transporter and killed the cells within 60 min. Additionally, nano-lipid particles of SfABCC2 were produced using styrene-maleic acid (SMA) to demonstrate the binding to Spore-Cry1Fa.

Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) and Bacillus subtilis (Bs) are rod-shaped, spore-forming, gram-positive bacteria often found in soil and hay. Bt was first discovered in Japan in 19011) as a virulent pathogen of Bombyx mori (the silkworm).2) Later, Berliner isolated the bacterium from Ephestia kuehniella (the Mediterranean flour moth) in a German state called Thüringen.3) Since then, this bacterium has been called B. thuringiensis named after Thüringen. During sporulation, Bt produces insecticidal proteins in a crystal-like formation, known as Cry proteins. Once the spores mature, Bt cells lyse and release free spores and crystals into the culture medium or environment. These spores and crystals are collected and formulated into sprayable insecticide products.

The HD1 strain of Bt, which is widely used in many sprayable Bt products,4) produces several Cry proteins including Cry1Aa, Cry1Ab, Cry1Ac, Cry1Ia, Cry2Aa, and possibly more. Unlike chemical insecticides, each Cry protein has a very narrow insect specificity. For example, Cry1Aa is highly effective against Trichoplusia ni (the cabbage looper) but less so against Chloridea virescens (previously known as Heliothis virescens, the tobacco budworm), whereas Cry1Ac shows the opposite specificity. The HD1 strain was chosen as a commercial product due to its diverse Cry protein components that work together to cover a wide range of insects.

Many Bt Cry proteins are typically protoxins of 135 kDa. When insects ingest the 135 kDa protoxin, it is activated to the 65 kDa mature toxin by trypsin-like serine proteases in the insect’s digestive fluid. There are two activation sites, one at Arg-28 and the other at Arg-618 in the case of Cry1Aa or corresponding Arg residues of other Cry proteins.5) The first 28 residues of Cry protoxin are known as the leader sequence. In our study, the leader sequence was included in the Cry1 protein when it was expressed on the spore surface, as it does not interfere with the cytotoxicity of mature toxins.6)

Since Bt Cry proteins act as toxins that target insects’ digestive tracts, they must be ingested to work effectively. A challenge with sprayable Bt products is their short field efficacy after application to crop plants, especially in hot and wet climates. Once sprayed on the plants, Bt quickly loses its effectiveness due to being washed off by rain and dew. Additionally, UV rays from the sun can deactivate the Bt Cry proteins. As a result, sprayable Bt products are not as widely used compared to chemical insecticides.

On the other hand, transgenic crops expressing Bt Cry proteins, such as Bt-corn and Bt-cotton, address the short field life of sprayable application. In Bt-crops, Cry proteins are consistently present in the plant tissue. Since Bt Cry proteins are potent feeding inhibitors, expressing the proteins in plants is highly effective in protecting crops continuously. The first Bt-corn expressing Cry1Ab to protect against Ostrinia nubilalis (the European corn borer) was developed by Estruch et al. in 1994.7) Since then, various Cry proteins have been utilized in Bt crops such as Cry1Ac in cotton to control C. virescens due to its high activity against this insect.8) According to a USDA report, over 80% of corn and cotton crops in the US are Bt-corn and Bt-cotton.9)

Due to the widespread use of Bt in sprayable products and transgenic crops, insects have developed resistance. The first report of insect resistance to Bt was published by Tabashnik et al. in 1990.10) Recently, resistant colonies of Spodoptera frugiperda (the fall armyworm) against Cry1Fa, which is highly toxic to this insect, were reported.11) The resistance was caused by mutations in Cry1Fa’s receptor, SfABCC2 (Spodoptera frugiperda ATP-binding cassette transporter, subfamily C, member 2), which exists on the epithelial cells of this insect’s midgut. It seems that a new Bt Cry protein that recognizes a receptor other than ABCC2 is necessary to overcome the resistance. Since Bt genes encoding Cry proteins are on large-size plasmids, new genes are being searched for by sequencing the plasmids using next-generation sequencing (NGS). After finding novel cry genes, the Cry protein encoded in each gene must be prepared and characterized, including determining its receptor. To characterize Cry proteins, the genes encoding the proteins have been cloned and expressed in a cry-negative Bt strain or E. coli. Hou et al.12) cloned a library of DNA-shuffled cry3Aa variants in an E. coli expression vector, pMAL. They developed a high throughput screening method for purifying 5000 shuffled proteins from an E. coli host harboring a DNA-shuffled library and characterized them, including their amino acid sequences and activity against corn rootworm larvae. However, this screening process is laborious and time consuming.

Alternatively, Bt Cry proteins have been displayed on E. coli phages.13–15) A library of Bt cry gene variants produced through discovery or protein engineering can be displayed and screened for receptor affinity. We have taken a different approach by displaying Bt Cry proteins on the surface of Bacillus subtilis (Bs) spores. Spore display technology has been successfully applied to enzymes, vaccines, and more.16) In our study, we attempted to display a Bt Cry protein on the surface of Bs spores to determine if such Cry proteins retain the ability to bind to their receptors. When a Cry protein is displayed on the spore surface, the receptor binding domain of the Cry protein, Domain II, must be exposed to the solvent in order to bind to the receptor molecule. To accomplish this goal, the N-terminus of the Cry1Fa protein was connected to the C-terminus of a spore outercoat protein using a structurally flexible linker. Our results indicated that Cry1Fa displayed on the spore could bind to its receptor expressed in Sf9 cells and extracted with SMA.

Bacillus subtilis (Bs) ISW1214 was obtained from Takara Bio, Shiga, Japan and used as the source of the cotC gene and the host of the Bt Cry protein spore display vector. The E. coli DH5α and dam/dcm-minus GM2163 strains were obtained from Thermo-Fisher Scientific, Tokyo, Japan, and New England Biolabs, Ipswitch, Massachusetts, U.S.A., respectively. The Bacillus-E. coli shuttle vector, pSB634 was obtained from Sandoz Agro, Palo Alto, California, U.S.A. This plasmid was described by Sasaki et al.,17) and its map is shown in Supplemental Fig. S1. Nucleotide sequences of the cotC gene and its promoter were obtained from the B. subtilis 168 genomic sequence (GenBank NC_000964.3). The sequence of the cotC gene is in Supplemental Fig. S2.

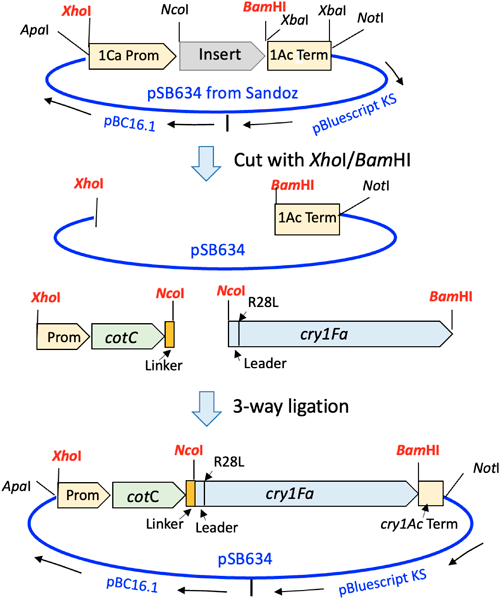

2. Construction of a spore display vector with the Bt cry1Fa geneThe Bs cotC gene along with its promoters (5′ upstream nucleotides) was amplified by PCR using the primers listed in Table 1 from a DNA sample extracted from Bs ISW1214. During the amplification, a flexible linker, GGGGSGGGGSAS, was attached at the 3′ end of the cotC genes. As shown in Fig. 1, the amplifications were done in two steps. In the first step, the cotC gene was amplified with Primer1F containing an XhoI site and Primer 2R containing a partial linker sequence. In the second step, the remaining linker sequence was added along with an NcoI site resulting in DNA sequences consisting of four elements: (i) an XhoI site, (ii) the promoter and cotC coding region, (iii) the linker, and (iv) an NcoI site. These PCR products were cloned into the pGEM-T easy plasmid obtained from Promega, Madison, Wisconsin, U.S.A.

| Primer1F (lowercase: XhoI) |

| cotC-F: 5′-GTATctcgagAAATCGTTTGGGCCG-3′ (28) |

| Primer2R (Bold: partial Linker) |

| cotC-R: 5′-TGAGCCGCCTCCTCCGTAGTGTTTTTTATG-3′ (30) |

| Primer3R (Bold: full Linker, lowercase: NcoI) |

| L1-R: 5′-CATAccatggTGATGCTGAGCCGCCTCCTCC-3′ (32) |

| L2-R: 5′-CATAccatggTGATGCTGATCCTCCTCCTCCTGAGCCGCCTCCTCC-3′ (33) |

The Bt cry1Fa gene encoding the leader sequence and mature toxin (1–615 aa) was synthesized by GenScript, Tokyo, Japan, using the nucleotide sequence from GenBank M63897.1 with NcoI and BamHI sites added at the 5′ and 3′ ends, respectively. This gene was then cloned into pGEM-T easy. Both the cotC and cry1Fa genes in pGEM-T easy were digested with XhoI, NcoI, and BamHI and purified by agarose gel electrophoresis. The final construct was created through a three-way ligation to clone the cotC gene with the linker and the cry1Fa gene into pSB634 as shown in Fig. 2. The final plasmid is composed of pSB634::cotC-L-cry1Fa-Term, where “L” and “Term” represent the linker and cry1Ac terminator, respectively. This spore display vector was constructed in E. coli DH5α, and the nucleotide sequence of the entire plasmid was confirmed through DNA sequencing.

The pSB634 vector containing the cotC and cry1Fa genes was transformed into E. coli GM2163 to obtain a methylation-minus DNA preparation. B. subtilis ISW1214 was then transformed by electroporation with the vector from E. coli GM2163 following a protocol provided by Takara Bio in its kit containing pHY300PLK and this Bs strain. The transformed Bs cells were spread on 1/2 LB-tet10 (10 µg/mL tetracycline) agar plates and incubated at 37°C for 72 hr for spore production. To prepare 1/2 LB (Luria–Bertani) agar, the amounts of casein peptone and yeast extract were reduced by half to facilitate complete sporulation. After full sporulation, spores were collected with 1 mL of TBS (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5 containing 150 mM NaCl) per plate and transferred to a 15 mL centrifuge tube. The tube was filled with TBS up to 14 mL, and the spores were suspended. The spores were then centrifuged at 14000×g for 30 min to obtain a precipitate. The spores in the precipitate were gently but fully suspended in 14 mL of TBS without forming air bubbles and centrifuged again at the same speed and time. The final precipitate was suspended in 1 mL of TBS. This spore suspension was examined under a microscope to confirm the absence of vegetative cells and determine the spore count. The spores of Bs ISW1214 lacking the cotC and cry1Fa genes were prepared using the same method. The Bs spore preparation procedure is illustrated in Supplemental Fig. S3. The spores were counted using a Neubauer cell counting chamber under a phase contrast microscope, or by observing colonies on LB-tet10 agar after dilution. The Bs spores expressing Bt Cry1Fa are referred to as Spore-Cry1Fa.

4. Confirmation of the expression of Cry1Fa on the surface of Bs sporesThe expression of Bt Cry1Fa proteins on the surface of Bs spores was confirmed through microscopic observation using an anti-Cry1Fa antibody. This antibody was produced in rabbits using a synthetic Cry1Fa peptide (602-ATFEAEYDLERAQK-615) as an antigen. The Cry1Fa antibody was purified using the Pierce Protein A IgG Purification Kit from Thermo-Fisher following the manufacturer’s protocol. The antibody was then labeled with Alexa Fluor 488 using the Alexa Fluor 488 Antibody Labeling Kit also obtained from Thermo-Fisher.

Spores-Cry1Fa (approx. 0.9×109 spores) were suspended in 1 mL of TBS and then mixed with 500 µL of an Alexa Fluor 488-labeled anti-Cry1Fa antibody in TBS. This mixture was incubated for 1 hr at 4°C followed by centrifugation at 12000×g for 10 min. The resulting precipitate was suspended in 1 mL of TBS to remove excess antibody and then centrifuged again under the same conditions. The final precipitate from the second centrifugation was suspended in 1 mL of TBS containing 0.02% Triton X-100 for observation under a fluorescence microscope. Triton X-100 was added to TBS to prevent spore aggregation during microscopic examination.

5. Cloning and expression of SfABCC2 in Sf9 cellsThe cDNA encoding the SfABCC2 protein (GenBank: MN399979.1) was synthesized by GenScript Japan. A FLAG tag (DYKDDDDK) was attached to the C-terminus of the protein. The SfABCC2 cDNA was cloned in the Bac-to-Bac Baculovirus Expression System obtained from Thermo-Fisher, following the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, transporter genes were cloned in pFastBac utilizing the AcMNPV polyhedrin promoter. The EGFP (Enhanced Green Fluorescent Protein) cDNA, which served as a marker, was also cloned in the same vector between NheI and SphI sites. The GFP gene was amplified from pEGFP-1 (Clontech Laboratories, Mountain View, California, U.S.A.). After the pFastBac-expression plasmid was transformed into DH10Bac cells, transposition occurred between the mini-Tn7 element on the pFastBac vector and the mini-attTn7 target site on the bacmid to generate a recombinant bacmid. After the transposition reaction was completed, the high molecular weight recombinant bacmid DNA was isolated, and Sf9 cells were transfected with the bacmid DNA using the ExpiFectamine Transfection Reagent to generate a recombinant baculovirus. After 72 hr, the media covering the cells was collected and clarified by centrifugation at 500×g for 5 min. The supernatant was used as a virus solution to infect Sf9 cells for the expression of SfABCC2. The Sf9 cells were maintained in Grace’s Supplemented Insect Media with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Thermo-Fisher) at 26°C. For Spore-Cry binding and cell viability assays, Sf9 cells with over 80% confluency were infected with the virus suspension. Infected Sf9 cells were then incubated at 26°C for 72 hr to express SfABCC2.

6. Binding of Spore-Cry1Fa to SfABCC2 expressed in Sf9 cellsTo determine if Spore-Cry1Fa binds to SfABCC2 expressed in Sf9 cells, Sf9 cells infected with baculovirus harboring an SfABCC2 expression construct were suspended in PBS (Phosphate Buffered Saline) containing 8.1 mM disodium phosphate, 1.5 mM monopotassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, 2.7 mM potassium chloride, and 137 mM NaCl in a cell culture dish. A piece of sterile microscope cover glass (22 mm×22 mm) was placed in the dish to allow the cells to settle on the cover glass. Spore-Cry1Fa labeled with an Alexa-tagged anti-Cry1Fa antibody as described in the previous section (Section 4) was suspended in PBS without Triton X-100 and added to the Sf9 cell suspension at a ratio of approximately 100 spores to 1 cell. After a brief incubation as short as 2 min, the cells in the culture dish were rinsed with PBS. The cover glass, on which cells were attached, was then removed from the dish, placed on a slide glass upside down, and individual Sf9 cells were examined under bright-field and fluorescence microscopes to detect bound Spore-Cry1Fa. It took about 10 min from the Spore-Cry1Fa mixing to the microscopic observation. Since mortality due to cell membrane degradation was observed in a few Sf9 cells, longer incubations of up to 60 min were made to confirm the mortality until almost the entire cell population appeared to be dead and disappeared due to the complete disintegration of the cell membrane. Sf9 cells infected with a baculovirus containing the vector without SfABCC2 (EGFP only) were prepared as a negative control.

7. Production of SfABCC2 transporter in B. mori pupaeThe SfABCC2 protein was produced in B. mori pupae. The synthesized SfABCC2 cDNA with a FLAG tag (DYKDDDDK) attached at its 3′ end was sent to Sysmex Corporation, Kobe, Japan to produce the proteins using their ProCube Technology.18) Briefly, the SfABCC2 cDNA was cloned in a baculovirus expression system to produce viruses. The recombinant baculovirus was then propagated in B. mori cells and injected into 10 pupae. The virus-infected B. mori pupae were homogenized by ultrasonication in TBS containing a protease inhibitor cocktail and a melanization inhibitor. The cell membrane fragments produced by sonication were collected through differential centrifugation as follows: (i) the homogenized pupal tissue was centrifuged at 1000×g to remove large-sized materials, (ii) the precipitate underwent further sonication and centrifugation, (iii) the supernatants of the low-speed centrifugations were combined and centrifuged at 100000×g for 1 hr to collect the precipitate, and finally, (iv) the precipitate was suspended in 10 mL of TBS. This 10 mL sample was divided into ten 1 mL aliquots (1 mL per pupa) and stored frozen at −80°C. We received these 1 mL aliquots referred to as “Membrane Fragments,” from Sysmex and used them to extract and purify the ABC transporter proteins.

8. Extraction of SfABCC2 with styrene-maleic acid and purificationThe SfABCC2 protein was extracted from Membrane Fragments using styrene-maleic acid (SMA). Styrene-maleic acid inserts into the membrane and creates small lipid particles called SMALP (Styrene-Maleic Acid Lipid Particles) containing SfABCC2 and surrounding phospholipids. A structural model of SMALP-SfABCC2 is depicted in Supplemental Fig. S4, Panel A. Ready-to-use powder SMA reagents were purchased from Cube Biotech, Monheim, Germany and dissolved in TBS at a 5% concentration. Four different SMA reagents were tested for the best solubility of SfABCC2 as shown in Supplemental Fig. S4. The Membrane Fragments prepared from silkworm pupae were mixed with an equal volume of 5% SMA in TBS and incubated at 25°C for 2 hr. The mixture was then centrifuged at 100000×g for 30 min at 4°C. The supernatant and precipitate were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blot using an anti-FLAG antibody to determine if SfABCC2 was extracted in the supernatant. As a control, SfABCC2 was extracted with 1% Triton X-100 using the same incubation and centrifugation conditions employed with SMA.

SMALP-SfABCC2 was purified using affinity chromatography with anti-FLAG antibody-immobilized agarose gel from MBL International Corp., Woburn, Massachusetts, U.S.A. One aliquot of 1 mL of the Membrane Fragments sample was divided into two 500 µL aliquots. A 500 µL aliquot estimated to contain approx. 150 µg of ABC transporter protein was mixed with 500 µL of 5% SMA, incubated, and then centrifuged to obtain approx. 1 mL of SMA-extracted SfABCC2. The SMA-extracted SfABCC2 was loaded onto 200 µL anti-FLAG antibody-immobilized agarose gel packed in a Pierce Spin Column from Thermo-Fisher. The column was washed three times with 500 µL of TBS containing 10% glycerol (TBS-glycerol), and SfABCC2 was eluted with 1.2 mL of elution buffer (0.1 mg/mL FLAG peptide in TBS-glycerol). The column eluate was fractionated into six 200 µL fractions and analyzed by dot blot.

All fractions (200 µL each) of the column eluate, except for the first fraction, were combined and concentrated using an Amicon Ultra Centrifugal Filter (50 kDa MW cutoff) purchased from MilliporeSigma, Saint Louis, Missouri, U.S.A., down to 300 µL. The concentrated column eluate was then desalted in a 2 mL Zeba Spin Desalting Column (Thermo-Fisher) and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blot using an anti-FLAG antibody. The affinity-purified, concentrated and desalted SMALP-SfABCC2 was divided into six 50 µL aliquots, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C.

9. Binding of SMALP-SfABCC2 to the Cry1Fa protein expressed on Bs sporesThe binding of SMALP-SfABCC2 to the Cry1Fa protein expressed on the surface of Bs spores was determined using 5000 spores suspended in 100 µL of TBS. A 50 µL aliquot of the column-purified and concentrated SMALP-SfABCC2 sample was added to this spore suspension. After a 10 min incubation, the mixture was transferred to a 500 µL centrifugal filter with a 0.45 µm filter, and the filter cup was filled with TBS-500 (TBS with 500 mM NaCl instead of 150 mM). The NaCl concentration was increased to minimize non-specific protein interactions. The filter was centrifuged at 10000×g for 10 min to collect Spore-Cry1Fa to which SMALP-SfABCC2 had bound. Unbound SMALP-SfABCC2 passed through the filter and was discarded. This centrifugation process was repeated two more times to ensure the removal of unbound ABCC2. After the final centrifugation, the filter cup was placed upside down in a 15 mL centrifuge tube, the bottom of the filter cup was filled with TBS-500, and then centrifuged at 5000×g for 5 min to recover the spores from the filter cup. The spore collection was repeated one more time, and all recovered spores were combined in an Eppendorf centrifuge tube. The spores were then spun down by centrifugation at 10000×g for 10 min. The precipitate was suspended in 20 µL of TBS, and SfABCC2 bound to Spore-Cry1Fa was analyzed by dot blot, SDS-PAGE and Western blot using an anti-FLAG antibody to detect the FLAG tag attached to SfABCC2’s C-terminus. Two identical setups were made for this binding experiment to produce a sufficient sample volume (40 µL) for the subsequent analyses.

To express Bt Cry1Fa on the surface of Bs spores, the Cry protein was attached to the CotC protein’s C-terminus via a structurally flexible linker to facilitate the assembly of the Cry protein without structural hindrance. The cotC–cry1Fa fusion was cloned in a shuttle vector, pSB634, which was constructed by combining pBC16.1 with pBluescript KS. The B. cereus replicon and a tetracycline-resistant marker in pBC16.1 were found to function effectively on 1/2 LB-tet10 agar in B. subtilis. The efficiency of transformation to B. subtilis ISW1214 ranged from 104 to 106 colony-forming units (CFU) per 1 µg of DNA depending on the preparation of competent cells. In most cases, the CFU was around 105. We used 1/2 LB in which amounts of casein peptone and yeast extract were reduced by half to facilitate complete sporulation. As shown in Fig. 3A, there were no vegetative cells in the spore sample. The expression of Cry1Fa on the spore surface was confirmed using an Alexa Fluor 488-labeled anti-Cry1Fa antibody as shown in Fig. 3B. Almost all spores visible under a bright-field microscope (Fig. 3A) appeared to be fluorescent (Fig. 3B), indicating that Cry1Fa was expressed on the spore surface and accessible by the antibody. Bs spores containing pSB634 only were also examined under a bright-field microscope as shown in Fig. 3C. No fluorescence was observed with the spores without Cry1Fa as shown in Fig. 3D indicating that the anti-Cry1Fa antibody was specific to Cry1Fa expressed on the spores.

Spore-Cry1Fa bound to Sf9 cells expressing SfABCC2 as shown in Fig. 4A–D within an incubation period as short as 2 min. However, these spores did not bind to Sf9 cells lacking SfABCC2 as shown in Fig. 4G and 4H. Bs spores without Cry1Fa (vector only) did not bind to Sf9 cells expressing SfABCC2 as shown in Fig. 4I and 4J. The binding of spores was confirmed using fluorescence microscopy with an Alexa Fluor 488-labeled anti-Cry1Fa antibody. In Fig. 4A and 4B, several instances of Spore-Cry1Fa are indicated by red arrowheads. These spores appeared as gray spots under bright-field microscopy (Fig. 4A) and as strong fluorescent spots under fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 4B). Figure 4D provides a typical example of Spore-Cry1Fa bound to the surface of Sf9 cells. The Sf9 cells exhibited weak fluorescence under a fluorescence microscope due to EGFP co-cloned with the transporter gene as a selection marker.

It appears that Spore-Cry1Fa is cytotoxic to Sf9 cells expressing SfABCC2. Figure 4A and 4B show a partially deformed cell as well as a completely disintegrated cell (highlighted in red circles). Figure 4E and 4F provide another example of a disintegrated Sf9 cell. This observation made after a 60 min incubation indicates that Cry1Fa is cytotoxic even when anchored on the spore surface. The disintegrated cell shown in Fig. 4E, as well as the red-circled cell in Fig. 4A at a shorter incubation, had no clear cell membrane visible under a bright-field microscope. On the other hand, fluorescence microscopic observations (Fig. 4B and 4F) of the disintegrated Sf9 cells revealed a bright lump. The lump may be a complex consisting of Spore-Cry1Fa and SfABCC2-lipid vesicles however we have not investigated the composition of such lumps in detail. The bright fluorescence signal is likely from Alexa Fluor 488 attached to the anti-Cry1Fa antibody which in turn binds to Spore-Cry1Fa in the lump. Cell mortality, defined in this study as cell membrane degradation and complete disintegration, was noted even in earlier stages of incubation such as 2 to 10 min.

Since the ABC transporter is a membrane-spanning protein, it is expected to be localized on the Sf9 cell membrane exposing extra-cellular loops (ECL) to which Cry1Fa’s Domain II (green) binds in a specific orientation as illustrated in Fig. 5. The C-terminal peptide (red) was chosen as the epitope of the anti-Cry1Fa antibody to prevent potential interference with the binding of Cry1Fa Domain II (green) to SfABCC2.

The cDNA encoding the FLAG-tagged SfABCC2 protein was synthesized and sent to Sysmex Corporation for production in B. mori pupae using their ProCube Technology. The TBS suspension of precipitate referred to as Membrane Fragments and supernatant samples from the final centrifugation at 100000×g were analyzed by Sysmex to confirm the production of SfABCC2. Figure 6A and 6B, show the results of Sysmex’s SDS-PAGE and Western blot analyses of the supernatant and precipitate. These analyses revealed that the majority of the SfABCC2 protein (150 kDa) was found in Membrane Fragments (Fig. 6A and 6B, Lane P), as indicated by red arrowheads.

SfABCC2 was extracted from Membrane Fragments using styrene-maleic acid (SMA). We purchased four SMA reagents with different polymerizations from Cube Biotech and evaluated them to determine the most effective solubilization rate for SfABCC2. As shown in Supplemental Fig. S4, Reagent 2 with a styrene-to-maleate ratio of 2.3 : 1 and a molecular weight of 6500 yielded the best result in terms of the amount of extracted SfABCC2. Under our experimental conditions, SMA extracted only a certain amount of SfABCC2 as shown in Fig. 6C and 6D. A significant portion of SfABCC2 was precipitated (Fig. 6C and 6D, Lane P) during centrifugation. It is possible that some SMA-extracted SfABCC2 was precipitated as the speed and duration of the centrifugation may have been too high and/or too long to keep the extracted SfABCC2 fraction in the supernatant. However, no further experiments were conducted after we obtained a sufficient amount of ABCC2 for subsequent experiments.

As a control, SfABCC2 was extracted from Membrane Fragments using 1% Triton X-100 under the same conditions as those of SMA. The yield of Triton X-100 extraction was analyzed by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 6E) and Western blot (Fig. 6F), and a similar yield was found compared to SMA. A significant amount of SfABCC2 remained insoluble in the precipitate faction. It appears that the low extraction efficiency is not specific to SMA.

4. Purification of SMALP-SfABCC2 by affinity chromatographySMALP-SfABCC2 was purified using affinity chromatography with anti-FLAG antibody-immobilized agarose. A sample of Membrane Fragments in 500 µL TBS was mixed with an equal volume of SMA reagent to create a 1 mL sample, which was then processed for one round of purification by affinity chromatography. SMALP-SfABCC2 was eluted with 1.2 mL of elution buffer (0.1 mg/mL FLAG peptide in TBS-glycerol) in six 200 µL fractions followed by a final spin-off at 1000×g for 1 min. These fractions and the final spin-off were analyzed by dot blot (Fig. 7A), combined into one 1.2 mL sample, concentrated in a centrifugal concentrator (50 kDa MW cutoff) down to 300 µL, and then desalted in a Sephadex G25 spin column to remove the FLAG peptide. The final sample was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blot as shown in Fig. 7B and 7C. The amount of SfABCC2 in the final 300 µL preparation was roughly estimated to be 30 µg.

To confirm that Cry1Fa anchored on the surface of Bs spores could bind to SfABCC2 extracted from the cell membrane, a binding experiment was conducted with purified SMALP-SfABCC2. Approximately 5000 Spore-Cry1Fa spores were allowed to bind to SMALP-SfABCC2. As a negative control, Bs spores without the cry1Fa gene (vector only) were used. After recovering Spore-Cry1Fa with bound SMALP-SfABCC2 from the centrifugal filter device, spore counts showed that spore recovery from the filter was about 20% meaning about 1000 spores were obtained. SfABCC2 bound to the spores was detected by Western and dot blots as shown in Fig. 8. The sample size for Western and dot blots shown in Fig. 8 was 10 µL per lane and per dot for SDS-PAGE followed by Western blot and dot blot. Due to the small sample size, no band was visible in the PAGE gel by Coomassie stain (the image is not shown), but Western blot revealed a positive band at 150 kDa (Fig. 8A, Lane 2 with a red arrowhead). There was no band with the spores without the cry1Fa gene (vector only) as shown in Lane 1 indicating that Cry1Fa on the spores, not the spore body, binds to SfABCC2. The result of the dot blot performed confirmed the binding as only Spore-Cry1Fa showed a positive reaction of SfABCC2 (Fig. 8B, Dots 2 and 3). No dot blot signal was observed with the spores lacking Cry1Fa (yellow circled Dot 1).

Since around 1960, Bt has been widely used in sprayable insecticide agents and transgenic plants such as Bt-corn and Bt-cotton. Due to its widespread use, insects have developed resistance to Bt. A recent example is Bt-corn expressing Cry1Fa, which was highly effective in controlling S. frugiperda before this insect developed resistance. The industry is now searching for the next generation of Bt Cry protein that will overcome the resistance to Cry1Fa.19) Wang et al.20) cloned and expressed several SfABC transporters, including SfABCA3, SfABCB1, SfABCC2, and SfABCC3, in Sf9 cells individually to determine the receptor specificity of Cry proteins by observing their cytotoxicity. They discovered that only Sf9 cells expressing SfABCC2 were killed by Cry1Fa, indicating that SfABCC2 is the receptor for Cry1Fa, and the cytotoxicity assay is useful for determining the receptor specificity of Bt Cry proteins. Using this cell assay, they also found that Cry1B killed Sf9 cells expressing SfABCB1.20) Since Cry1B targets a different receptor than Cry1Fa, it can overcome S. frugiperda’s resistance to Cry1Fa. Therefore, Cry1B has been chosen as a potential next generation Cry protein for Bt-corn. Nevertheless, the activity of Cry1B against S. frugiperda is not high enough for commercial application in Bt-corn. The industry is working on engineering Bt Cry proteins for higher activity primarily using domain swapping such as Cry1B.868.20) While this technology is useful, other protein engineering technologies have been utilized such as DNA shuffling and saturation mutagenesis.21) These protein engineering technologies generate numerous variants of Cry1B, which are then screened for increased activity through high throughput protein production and insect bioassay. However, the screening process, especially insect bioassay, is both laborious and time-consuming.

In our cell assay, the primary goal was to determine if Cry1Fa displayed on the spore surface binds to SfABCC2 expressed in Sf9 cells. Microscopic observations showed that Spore-Cry1Fa attached to the surface of Sf9 cell where SfABCC2 is expected. This indicates that the receptor binding domain of Cry1Fa (Domain II) on the spore is facing towards the extra cellular loops of SfABCC2 allowing the binding to the receptor as depicted in Fig. 5. We unexpectedly discovered that Spore-Cry1Fa is quite cytotoxic to Sf9 cells expressing the receptor for Cry1Fa. Microscopic observations have revealed that Spore-Cry1Fa causes partial and complete disintegration of the cell membrane of Sf9 cells when they are expressing SfABCC2. According to Wang et al.,20) freely soluble Cry1Fa kills Sf9 cells expressing SfABCC2. It is uncertain if these cytotoxic reactions are the same between spore-bound and free Cry1Fa proteins. Nevertheless, the cytotoxicity of Cry proteins likely occurs only after the protein binds to the receptor. Sf9 cells originally established from ovarian tissue of S. frugiperda differ from midgut epithelial cells where Cry protein targets. The mode of action of Bt Cry proteins may not be the same between Sf9 and the epithelial cells. Further study is necessary to evaluate the toxicity of Cry proteins against whole insects based on the cell assay.

Screening Cry proteins for cell mortality can be completed in microtiter plates in a few hours while a whole insect assay can take days. Furthermore, the results of a cell mortality assay can be read by a plate reader using a chemical cell viability assay kit such as Promega’s CellTiter-Glo® Assay Kit. In 2016, Willcoxon et al.22) demonstrated the potential of using a cell assay for high throughput screening of a library of Bt Cry protein variants. They used Sf21 insect and EXPi293F mammalian cells in which a Bt receptor gene had been cloned and expressed, CellTiter 96® Kit for cell viability, and 96-well microtiter plates to demonstrate a dose-response assay with various concentrations of Bt Cry protein. These chemical cell viability assays are useful for quantitatively determining the cytotoxicity of free Cry proteins, but we did not include it in our study as our goal is to establish the binding of Spore-Cry1Fa to SfABCC2 (Cry1Fa’s receptor) expressed in Sf9 cells.

Our spore display system is not designed to quantitatively determine the affinity level of any Cry protein to the target receptor in Sf9 cells, and the observed cytotoxicity prevents such determination. To conduct a quantitative assay, the doses of Cry proteins used in the assay must be determined. We lack information on (i) the amount of Cry protein expressed on the spore surface and (ii) the portion of the protein involved in receptor binding and subsequent cytotoxicity. In our study, Cry1Fa was linked to a Bs spore outercoat CotC protein through covalent bonding. The CotC–Cry fusion protein is intended to cover the entire Bs spore surface with only a small fraction of these protein molecules responsible for binding to the receptor on the cell membrane, similar to how two spherical objects attach through small contact areas. To progress beyond the qualitative cell assay presented in this study, specific methods are necessary to quantify the amount of the Cot–Cry fusion protein. In the future, this could be accomplished through ELISA using an antibody specific to an epitope of the Cry protein. The epitope must be exposed to the solvent or fully accessible to the antibody. Another method could involve analyzing a Cry protein-specific peptide by mass spectrometry after complete digestion of the Cry protein.

B. subtilis spore display technology has been utilized to engineer proteins such as vaccines and industrial enzymes.16) However, there have been no reports of applying the technology to Bt Cry proteins. In this study, we demonstrated that Cry proteins displayed on the surface of Bs spores are functional in terms of receptor binding. A library of Bt Cry protein variants produced through protein engineering can be created and displayed on Bs spores. These variants can then be screened for biological and biochemical functions. For example, a Bt receptor can be immobilized on a supporting material to screen Bs spores expressing a Cry protein library, similar to affinity chromatography. Each spore would express a unique variant of the Bt Cry protein. Alternatively, individual Bs spores expressing a Cry protein library can be sorted by a cell sorter using fluorescent SMALP-ABC transporter particles as it has been suggested.23) After screening the library and identifying spores with interesting characteristics, the sequence of the Cry protein on the spores can be determined by sequencing the plasmid within the spores. Essentially, the spore serves as a sequence information tag for the Cry proteins being screened, eliminating the need to screen samples individually as we have done with soluble Cry proteins.

To express a Bt Cry protein on Bs spores, we used pSB634, a Bacillus–E. coli shuttle vector created by Sandoz Agro using pBC16.1 and pBluescript. Sandoz Agro shared this plasmid with collaborators including us at Hokkaido University to clone and express a Bt cry gene in Bt for producing the Cry protein in its crystal form. Our study demonstrated the effectiveness of this plasmid as a vector for Bs spore display. In addition to pSB634, we also used pHY300PLK from Takara Bio and achieved similar results compared to those obtained with pSB634.23) The pHY300 vector had previously been used by Han and Enomoto for displaying a cholera vaccine.24) The spore display technology has utilized various Bs outercoat proteins such as CotC, CotG, and CotB. In our research, we substituted CotC with CotG and achieved comparable results in terms of Cry protein expression and cytotoxicity compared to CotC.23) We also displayed Cry1Aa and observed that the spore was cytotoxic to Sf9 cells expressing ABCC2 of B. mori (BmABCC2).23) We are confident that the spore display technology can be successfully utilized with Bt Cry proteins.

In our study, the SfABCC2 protein was extracted from the silkworm cell membrane using SMA and purified through affinity chromatography to observe its binding to Spore-Cry1Fa. A structural model of SMA-extracted SfABCC2 is presented in Supplemental Fig. S4, Panel A. As shown in this model, SMA preserves the structural integrity of membrane proteins with their surrounding phospholipids as reported with other membrane proteins.25) In contrast, detergents such as Triton X100, when used to solubilize membrane proteins,26) may displace phospholipids and potentially alter the protein structure as depicted in Supplemental Fig. S4.

When an insect larva ingests the Cry1Fa protoxin, a trypsin-like protease in the insect’s digestive fluid cleaves the protoxin at the carboxyl side of Arg-27 and Arg-612 to activate it into the mature toxin.5) The mature toxin is resistant to further protease digestion unless potential structural changes occur after binding to a receptor. In our study, Arg-27 was mutated to Leu (R27L) to prevent the detachment of the Cry protein from Bs spores by protease digestion. B. subtilis releases proteases into the culture medium when sporulated and lysed. The R27L-mutated Cry1 protein expressed on the spore surface appeared to be resistant to Bs proteases throughout spore purification and subsequent experiments. Additionally, it seems that the Cry protein was not digested by internal proteases of Sf9 cells after binding to the receptor and subsequent cell disintegration as the spores were retained on the surface of Sf9 cells during incubation as shown in Fig. 4. It is unknown how Cry protein on the surface of Bs spores disrupts the cell membrane of Sf cells expressing a Bt receptor after binding to the cell membrane. Further studies are needed to understand the mode of action of the Cry protein expressed on the Bs spore surface.

This study was financially supported by a grant from Syngenta Crop Protection LLC to Hokkaido University. Syngenta and Hokkaido University co-own the intellectual property resulting from this study and have jointly filed a patent application related to this study. There are no other conflicts of interest.

SK conducted most of the experiments under the direct supervision of SA who also contributed to specific experiments such as baculovirus-mediated cloning of transporter genes into the Sf9 cell. PO played a significant role in leading the overall research direction and developing experimental designs. TY conceived the ideas of extracting ABCC2 using SMA and applying spore display technology to Bt Cry proteins including the vector design.

We would like to express our gratitude to Syngenta scientists Matt Bramlett, Eric Chen, Chris Fleming, Mike Reynolds and Jun Zhang for their input and support throughout the project including their critical review of the manuscript.

The online version of this article contains supplementary materials (Fig. S1–S4) which are available at https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/browse/jpestics/