2013 Volume 63 Issue 1 Pages 96-103

2013 Volume 63 Issue 1 Pages 96-103

In order to produce triploid plants, 2n female gametes were induced by treating female buds and developing embryo sacs of Populus adenopoda Maxim with high temperature exposure. During megasporogenesis, tests were conducted on the relationship between female gametophyte development and morphological changes of female catkins. In the resulting progeny, 12 triploids were produced, and the highest rate of triploid production was 40%. Cytological observation revealed that the pachytene to diakinesis phase of meiotic stages may be a suitable period for inducing megaspore chromosome doubling through high temperature exposure. On the other hand, catkins of 6–72 h after pollination were treated for inducing embryo sac chromosome doubling. In the offspring seedlings, 51 triploids were detected and the highest efficiency of triploid production was 83.33%. Correlation analysis between the proportion of each embryo sac’s developmental stage and the percentage of triploid production indicated that the second mitotic division may be the most effective stage for 2n female gamete induction. Our findings showed that high temperature exposure is an ideal method for 2n female gamete induction. Heterozygous offspring are valuable for breeding programs of P. adenopoda.

White poplar, Populus adenopoda Maxim (section Populus, family Salicaceae, genus Populus) which grows at 800–1,800 m altitudes in mountainous regions, is a timber species native to China. Thanks to its high growth rate and good timber quality, it is used widely for landscape cultivation, ecological protection and the production of lumber and pulp in southern China (Wang et al. 2006). In recent years, the forest industry has shown a particular interest in planting populus and its hybrids for its high-yield fiber production, since the wood supply is emerging as a constraint on development and an increasing amount of the land base in the plains of southern China is becoming unavailable for exploitation. A breeding program for P. adenopoda has been developed by the Beijing Forestry University in cooperation with the Hunan Academy of Forestry.

The heterosis of triploid populus has valuable characteristics, such as greater growth vigour, better timber quality and higher stress resistance in comparison with their diploid counterparts (Buijtenen et al. 1958, Einspahr 1984, Nilsson-Ehle 1936, Weisgerber et al. 1980, Zhu et al. 1998). Thus, the triploid breeding plan has become a part of the populus genetic improvement program. Triploid hybrid populus clones with good performance were obtained in P. tomentosa (Zhu et al. 1998) and the section Aigeiros (Zhang et al. 2004). These triploid populus clones were achieved by 2n pollen crossed with normal female gametes. However, Kang et al. (1997) reported that the incidence of triploids was low because 2n pollen had less chance of fertilizing female gametes when in competition with normal pollen.

In recent years, utilization of 2n female gametes to increase the incidence of triploids has been proven to be a more effective approach to produce triploid Populus (Li et al. 2008, Wang et al. 2010, 2012). Li et al. (2008) successfully induced 2n eggs by treating Populus alba × Populus glandulosa female buds with colchicine treatment during macrosporogenesis, and produced 12 triploid hybrids. Wang et al. (2010, 2012) reported that induction of 2n female gametes during macrosporogenesis and embryo sac development of Populus pseudo-simonii Kitag. × Populus nigra L. ‘Zheyin3#’ female catkins treated with high temperature exposure and colchicine, obtaining 66.7% triploid production. Thus, induction of 2n female gametes during macrosporogenesis and embryo sac development is an appropriate method for effective triploid production.

High temperature exposure, as a physical mutagenic agent, is often used to induce polyploid in plants for its operational advantages and uniformity of treatments (Kang et al. 2000a, Mashkina et al. 1989, Randolph 1932, Wang et al. 2012, Zhang et al. 2002). In Populus, 2n gamete was induced successfully with high temperature exposure. Kang et al. (2000a) induced more than 80% 2n male gametes with high temperature exposure in Populus tomentosa × Populus bolleena and the frequency of artificial 2n female gametes was 66.7% by high temperature treatment in Populus ‘Zheyin3#’ (Wang et al. 2012).

Artificial triploid induction of P. adenopoda has been attempted by Hou (2007) and Liu (2009). However, no polyploidy was obtained. The objective of our research is, based on the cytological observation of female gametophyte development in P. adenopoda, to investigate its efficiency of triploid induction by high temperature exposure during megasporogenesis and embryo sac development.

The mother branches of P. adenopoda (2n = 2x = 38) were collected from a natural forest stand in the suburb of Guiyang (1340 m alt., 26°63′N, 106°75′E), Guizhou province. Some male floral branches (2n = 2x = 38) were selected from the same forest stand as that of the mother branches. Other male floral branches were gathered from the Qingtianping forest farm of Xiangxi Autonomous Prefecture at 860 m altitude (27°44′N, 109°10′E), Hunan province. All sampled branches were trimmed and cultured in a greenhouse (10–20°C) at Beijing Forestry University to force floral development.

Determination of developmental process of female gametophyteTo investigate the megaspore mother cells (MMCs) of P. adenopoda, after the branches were cultured in the greenhouse, female catkins were sampled every 12 h before pollination. For observation of the development of embryo sacs, female catkins were sampled every 6 h after pollination until seed maturity. The sampled catkins were fixed in FAA (70% ethanol/acetic acid/40% formaldehyde, 90 : 5 : 5) at 4°C for 24 h. Before being fixed, the morphological characteristic of the catkins were recorded.

Ovaries from each fixed catkin were randomly removed, dehydrated in alcohol, embedded with paraffin and sectioned between 8–10 μm. The sections were stained with iron hematoxylin and photographed under an Olympus BX51 microscope. At least three catkins were sampled and 60 ovules were used for statistical analysis.

High temperature treatmentAfter associating the development of female gametophytes with flower morphological characteristics, catkins and pollinated inflorescences at different morphological stages were exposed to 38°C, 41°C and 44°C for 4 and 6 h. Untreated catkins served as the control group.

When stigmas of treated catkins were at the receptive stage, pollination was conducted with fresh pollen of P. adenopoda. The female floral branches were further hydroponically cultured. Seeds were harvested after approximately 3 weeks. They were sown in clay pots in a greenhouse and seedlings were implanted into nutrition pots after 5 cm in height to promote growth.

Ploidy analysis by flow cytometryFlow cytometry measurement was performed using a flow cytometer (BD FACSCalibur USA). About 0.5 g of young leaves were chopped with a sharp blade in a 55-mm Petri dish containing nuclei extraction solution (Galbraith et al. 1983) (0.2 mM Tris-HCl, 45 mM MgCl2, 30 mM sodium citrate, 20 mM 4-morpholinepropane sulfonate, 1% (v/v) Triton X-100, pH 7.0) and then filtered through a 40 μm nylon mesh. The suspension of released nuclei was stained with 50 μl of 4′, 6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, 10 mg/ml) for 5 min. The leaf sample from a known diploid plant of P. adenopoda was used as control. The standard peak was managed to appear at about channel 50 of relative fluorescent intensity.

Chromosome countingThe ploidy level of each plantlet was ultimately confirmed by chromosome counting. Stem tips were excised from the seedlings and pretreated in a saturated solution of para dichloro benzene for 4 h, then washed once and fixed in fresh Carnoy’s fluid (ethanol/acetic acid, 3 : 1) for at least 24 h under 4°C. Fixed stem tips were hydrolyzed in 38% HCl/ethanol (1 : 1) for 10 min at room temperature and then rinsed with distilled water for 10 min. The hydrolyzed samples were stained with Carbol fuchsin, squashed with a cover slip and then observed at 100× oil lense magnification using an Olympus BX51 microscope.

Statistical analysisThe rate of triploid production induced by megaspore chromosome doubling was analyzed by GLM-Univariate to reveal the differences between floral characteristics, temperatures and treatment durations. Prior to analysis, data of the percent triploid production rate were transformed by the arc-sin of the square root of p/100. The rate of total triploid production at different floral morphological characteristics and the percentage of certain female gametophyte stages were evaluated by pearson’s correlation coefficient. All statistical analyses were achieved by the statistical program SPSS Software Version 17.0.

The relationship between flower bud morphological characteristics and the female meiotic stage was studied to guide high-temperature treatments (Table 1). More than one meiotic stage was observed in each sampled female bud due to asynchronous development of MMCs in different ovaries. When the catkin was wrapped by bract scales (Fig. 1A), some MMCs (25.0%) (Fig. 2A) began to undergo female meiosis and most MMCs had been in leptotene (Fig. 2B, 2C). The female buds were characterized by catkins which emerged from bract scales slightly (Fig. 1B), corresponding with late leptotene (21.19%) to pachytene (39.83%) of MMCs (Fig. 2D). Approximately one fourth of the catkins protruded from the bract scales (Fig. 1C), major MMCs were in diplotene (35.35%) and diakinesis (31.31%) (Fig. 2E, 2F). When approximately one third of the catkins emerged outside the squama of buds (Fig. 1D), the proportion of MMCs at metaphase I (Fig. 2G) was predominant (28.99%). The catkins occurred when approximately two thirds of the catkins emerged from the bract scales (Fig. 1E), corresponding to most MMCs at anaphase I (43.04%) (Fig. 2H). When approximately three-quarters of the catkins emerged outside the bract scales of the buds (Fig. 1F), most MMCs were in prophase II (37.14%) (Fig. 2I) to metaphase II (25.71%) (Fig. 2J) and a few cells had developed into anaphase II (Fig. 2K) and tetrad (Fig. 2L).

| Developmental stage of MMCs | Floral morphological characteristics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without uncovered catkina | Slightly uncovered catkin | 1/4 uncovered catkin | 1/3 uncovered catkin | 2/3 uncovered catkin | 3/4 uncovered catkin | |

| MMCs | 25.0%b (23c) | 13.56% (16) | ||||

| Early leptotene | 31.52% (29) | 17.80% (21) | ||||

| Late leptotene | 33.70% (31) | 21.19% (25) | 15.15% (15) | 15.94% (11) | ||

| Pachytene | 9.78% (9) | 39.83% (47) | 18.18% (18) | 13.04% (9) | ||

| Diplotene | 7.63% (9) | 35.35% (35) | 20.29% (14) | |||

| Diakinesis | 31.31% (31) | 21.74% (15) | 11.39% (9) | |||

| Metaphase I | 28.99% (20) | 25.32% (20) | ||||

| Anaphase I | 43.04% (34) | 21.43% (15) | ||||

| Prophase II | 15.19% (12) | 37.14% (26) | ||||

| Metaphase II | 5.06% (4) | 25.71% (18) | ||||

| Anaphase II | 11.43% (8) | |||||

| Tetrad | 4.29% (3) | |||||

Female bud morphological characteristics of P. adenopoda. Scale bar = 5 mm. (A) Without uncovered catkin, of which the catkin was wrapped by bract scales. (B) Slightly uncovered catkin, of which the catkin emerged from bract scales slightly. (C) 1/4 uncovered catkin, approximately one fourth of the catkin protruded from the bract scales. (D) 1/3 uncovered catkin, approximately one third of the catkin emerged from the bract scales. (E) 2/3 uncovered catkin, approximately two thirds of the catkin emerged from the bract scales. (F) 3/4 uncovered catkin, approximately three-quarters of the catkin emerged from the bract scales.

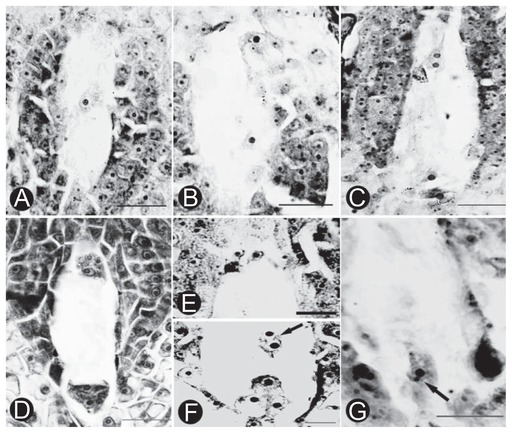

MMCs of P. adenopoda meiosis. Scale bar = 20 μm. (A) MMC. (B) Early leptotene. (C) Late leptotene. (D) Pachytene. (E) Diplotene. (F) Diakinesis. (G) Metaphase I. (H) Anaphase I. (I) Prophase II. (J) Metaphase II. (K) Anaphase II. (L) Tetrad.

Table 2 presents the rate of triploid production of catkins exposed to high temperature at different bud morphological characteristics. After female buds were treated with high temperature exposure, bud development was retarded, and the stigmas became dry and brown. Some buds treated with high temperature died, resulting in no seed collection for some treatments. A total of 2190 seeds were produced from treated catkins and the control group, 879 offspring were produced after sowing that survived to be scored later in the experiment. Individual seedlings were described as diploid or triploid according to the peaks obtained by flow cytometry. Finally, 12 triploids were screened. Representative examples are illustrated in Fig. 3 (A, C). Cytological observation of stem tip cells confirmed that all these seedlings were triploids with 57 chromosomes (Fig. 3D), indicating that they were true triploids. No triploids occurred in the control group, suggesting that 2n egg formation and fertilization between normal eggs and 2n pollen occurs rarely.

| Floral morphological characteristics | Treatment temperature (°C) | Treatment duration (h) | Seed number | Seedling number | Triploid number | Rate of triploids (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without uncovered catkin | 38 | 4 | 103 | 32 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 15 | 2 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 41 | 4 | 172 | 54 | 0 | 0 | |

| 6 | — | — | — | — | ||

| 44 | 4 | 37 | 10 | 0 | 0 | |

| 6 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Slightly uncovered catkin | 38 | 4 | 57 | 19 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 97 | 42 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 41 | 4 | 72 | 38 | 1 | 2.63 | |

| 6 | 89 | 35 | 1 | 2.86 | ||

| 44 | 4 | 247 | 65 | 0 | 0 | |

| 6 | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1/4 uncovered catkin | 38 | 4 | 36 | 14 | 2 | 14.3 |

| 6 | 43 | 15 | 6 | 40 | ||

| 41 | 4 | 35 | 11 | 2 | 18.18 | |

| 6 | 65 | 18 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 44 | 4 | — | — | — | — | |

| 6 | 17 | 2 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 1/3 uncovered catkin | 38 | 4 | 76 | 31 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 105 | 32 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 41 | 4 | 21 | 8 | 0 | 0 | |

| 6 | — | — | — | — | ||

| 44 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 6 | 10 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 2/3 uncovered catkin | 38 | 4 | 142 | 54 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 57 | 25 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 41 | 4 | 64 | 16 | 0 | 0 | |

| 6 | 28 | 9 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 44 | 4 | 80 | 21 | 0 | 0 | |

| 6 | — | — | — | — | ||

| 3/4 uncovered catkin | 38 | 4 | 81 | 46 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 45 | 15 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 41 | 4 | — | — | — | — | |

| 6 | 69 | 16 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 44 | 4 | 14 | 3 | 0 | 0 | |

| 6 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Control | 295 | 243 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Total | 2190 | 879 | 12 |

Ploidy level detection of offspring derived from megaspore chromosome doubling with high temperature in P. adenopoda. (A) Flow cytometric analysis of diploid plant (control). (B) Chromosome number of diploid plant (2n = 2x = 38). Scale bar = 20 μm. (C) Flow cytometric analysis of triploid plant. (D) Chromosome number of triploid plant (2n = 3x = 57). Scale bar = 20 μm.

According to the data on triploid production ratio (Table 2), GLM-Univariate analysis indicated significant differences among the female bud characteristics observed (F = 4.095, p = 0.009). The differences of treatment temperatures (F = 0.771, p = 0.475) and treatment durations (F = 0.343, p = 0.564) were not significant.

Pearson’s correlation analyses between the percentage of certain meiotic stages and the rate of triploid production indicated that the percentage of sum triploid production at different female characteristics was positively correlated with the percentages of pachytene (r = 0.495, p = 0.505), diplotene (r = 0.437, p = 0.712) and diakinesis (r = 0.855, p = 0.348). However, the rate of total triploid production at different female bud stages had a negative correlation coefficient with the percentages of MMCs, early leptotene (r = −1.0** and r = −1.0**) and late leptotene (r = −0.507, p = 0.493), respectively. This suggested that induced 2n eggs may be derived from female meiotic pachytene to diakinesis during macrosporogenesis.

Embryo sac chromosome doubling induced by high temperature exposureEmbryo sac development of P. adenopoda belonged to the typical polygonum-type (Fan and Wu 1982). Functional megaspores formed a 7-celled mature embryo sac via three sequential mitotic divisions (Fig. 4). The mature embryo sac consisted of three antipodal cells (Fig. 4E), a central cell, an egg cell and two synergid cells (Fig. 4F).

Embryo sac development of P. adenopoda. Scale bar = 20 μm. (A) Uni-nucleate embryo sac. (B) Two-nucleate embryo sac. (C) Four-nucleate embryo sac. (D) Eight-nucleate embryo sac. (E–F) Mature embryo sac consisted of three antipodal cells (E), a central cell with two polar nuclei (arrow) and one egg apparatus (F). (G) Fertilization (Arrowhead shows one sperm is close to egg).

The embryo sac development was a consecutive and asynchronous process (Table 3). In general, it began before stigma receptivity of P. adenopoda was initiated. Three micropylar megaspores of a tetrad initiated to degenerate and the enlarged functional megaspore at the chalazal end formed a uni-nucleate embryo sac (Fig. 4A). Six hours after pollination, the uni-nucleate embryo sac was predominant (51.43%). Other stages, such as functional megaspore, the two-nucleate embryo sac (Fig. 4B), the four-nucleate sac (Fig. 4C) and even the eight-nucleate sac (Fig. 4D), were also observed. Twelve hours after pollination, the occurrence of the two-nucleate embryo sac was dominant (44.29%). With the development of embryo sacs, the proportion of four-nucleate embryo sacs increased gradually, showing greater percentages than other stages 18–30 h after pollination. After that, all cells developed into eight-nucleate and mature embryo sacs in succession. Fertilization occurred between 48 h and 72 h after pollination (Fig. 4G).

| Hours after pollination | Developmental stage of embryo sac | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Functional megaspore | Uni-nucleate embryo sac | Two-nucleate embryo sac | Four-nucleate embryo sac | Eight-nucleate embryo sac and mature embryo sac | Fertilization and post | |

| 6 | 7.14%a (5b) | 51.43% (36) | 34.29% (24) | 5.71% (4) | 1.43% (1) | |

| 12 | 1.43% (1) | 31.43% (22) | 44.29% (31) | 18.57% (13) | 4.29% (3) | |

| 18 | 23.61% (14) | 31.94% (23) | 37.50% (27) | 11.11% (8) | ||

| 24 | 13.70% (10) | 24.66% (18) | 41.10% (30) | 20.55% (15) | ||

| 30 | 9.86% (7) | 23.94% (17) | 35.21% (25) | 30.99% (22) | ||

| 36 | 13.24% (9) | 17.65% (12) | 30.88% (21) | 38.24% (26) | ||

| 42 | 9.52% (6) | 12.70% (8) | 28.57% (18) | 49.21% (31) | ||

| 48 | 1.67% (1) | 16.67% (10) | 26.67% (16) | 46.67% (28) | 8.33% (5) | |

| 72 | 4.55% (3) | 12.12% (8) | 19.70% (13) | 63.64% (42) | ||

Table 4 shows that 51 triploids were obtained by treating pollinated catkins of P. adenopoda to induce embryo sac chromosome doubling with high temperature exposure. All triploid offspring were confirmed by flow cytometry and identified by chromosome counting (2n = 3x = 57, Fig. 5A, 5B). There were no triploid seedlings obtained in the control treatment. A total of 34 triploids were obtained from the treatments 12–24 h after pollination, representing 66.67% of the sum of all triploids. Among all treatments, the highest percentage of triploid occurrence was 83.33%, which occurred 18 h after pollination.

| Hours after pollination | Treatment temperatur (°C) | Treatment duration (h) | Cross combination (♀×♂) | Seed number | Seedling number | Triploid number | Triploid production rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 44 | 4 | Guizhou × Hunan | 24 | 11 | 3 | 27.27 |

| 12 | 41 | 4 | Guizhou × Guizhou | 86 | 32 | 12 | 37.5 |

| 18 | 38 | 6 | Guizhou × Hunan | 99 | 18 | 15 | 83.33 |

| 24 | 41 | 6 | Guizhou × Guizhou | 86 | 20 | 7 | 35 |

| 30 | 41 | 6 | Guizhou × Guizhou | 140 | 75 | 10 | 13.33 |

| 36 | 38 | 6 | Guizhou × Hunan | 495 | 281 | 4 | 1.42 |

| 42 | 44 | 4 | Guizhou × Hunan | 15 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| 48 | 44 | 6 | Guizhou × Hunan | 18 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| 72 | 38 | 4 | Guizhou × Hunan | 72 | 56 | 0 | 0 |

| Control | Guizhou × Hunan | 682 | 623 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Guizhou × Guizhou | 436 | 391 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Total | 2153 | 1516 | 51 |

Ploidy level detection of offspring derived from embryo sac chromosome doubling with high temperature in P. adenopoda. (A) Flow cytometric detection of nuclei mixture of young leaves from diploid and triploid seedings. (B) Somatic chromosome number of triploid (2n = 3x = 57). Scale bar = 20 μm.

Pearson’s correlation analyses were made between the percentage of each developmental stage of the embryo sacs and the ratio of triploid production. A significant positive correlation between the percentage of the two-nucleate embryo sacs and the ratio of triploid production (r = 0.681, p = 0.043) was observed. However, a negatively correlation was found between the percentage of the eight-nucleate embryo sacs and the ratio of triploid production (r = −0.657, p = 0.054). There were no significant correlations between the ratio of triploids and the percentages of uni- and four-nucleate embryo sacs (r = 0.432, p = 0.285 and r = 0.278, p = 0.470, respectively).

It is well known, that there are some evident advantages of triploid Populus cultivars over diploid ones, for example (1) they produce larger leaves and higher yields, (2) they show better leaf quality and higher resistance to a number of leaf diseases, (3) multiple copies of gene alleles accumulate in the resulting hybrids, which are expected to show gene dosage effect and heterosis and (4) they normally have sterile pollens so as to avoid pollen pollution to surroundings, reducing risks to the human population that is sensitive to pollen (Zhu 2006). Currently, triploid Populus clones, which are obtained by 2n pollen crossing with normal female gametes, are widely planted in China (Zhang et al. 2005, Zhu 2006). However, the efficiency of triploid production through pollination with induced 2n pollen was low (12.9% at most, published in Kang et al. 2000b), due to competition from normal pollen (Kang and Zhu 1997). In this study, we used high temperature exposure to induce megaspore and embryo sac chromosome doubling and successfully produced 63 triploid plants (83.33% at most) of Populus, suggesting that hybridization with induced 2n female gametes is a more effective approach for triploid production in Populus.

Colchicine has been widely used to induce polyploids in plants (Eigsti and Dustin 1955). In their polyploid breeding program of white Populus, Kang et al. (2004) obtained 21 triploids (51.7% highest production rate) through embryo sac chromosome doubling with colchicine solution. Li et al. (2008) achieved 12 triploids (16.7% highest production rate) through megaspore chromosome doubling with colchicine solution. In the present study, high temperature treatments showed a better outcome in embryo sac chromosome doubling (51 triploids and 83.33% production efficiency), demonstrating that high temperature exposure is more suitable for 2n female gamete induction of Populus than colchicine. However, since the response of female gametophytes to high temperatures can vary according to genotype (Wahid et al. 2007), the temperature range and duration should be adjusted accordingly.

Applying a mutagenic agent to cells at a suitable stage is vital for chromosome doubling. The pachytene stage of meiosis was observed to be optimal for colchicines-induced 2n megaspore induction of Populus alba × P. glandulosa (Li et al. 2008). The most suitable stage for 2n megaspore induction with high temperature exposure was from pachytene to diplotene in Populus pseudo-simonii × Populus nigra ‘Zheyin3#’ (Wang et al. 2012). In the present study, the most suitable stage for 2n megaspore induction with high temperature was from pachytene to diakinesis in P. adenopodar. To some extent, the suitable stage was later than with previously studied Populus, possibly because development of the MMCs in P. adenopodar was faster than the former and the permeability of different induction methods to the mega-spore may be very different.

The triploid proportion induced by embryo sac chromosome doubling in P. tomentosa × P. bolleana (Kang et al. 2004) and Populus pseudo-simonii × Populus nigra ‘Zheyin3#’ (Wang et al. 2010) was more than 50%, and the highest efficiency of triploid induction in this study was 83.33%. Wang reported that four-nucleate embryo sacs may be the most effective stage to induce 2n eggs. However, correlation analyses in the present study showed that the percentage of triploid production was significant positively correlated with the percentage of two-nucleate embryo sacs, suggesting that the second mitotic division during embryo sac development may be effective for 2n egg induction of P. adenopodar.

In general, tolerance to heat stress varies among different plant organs; ovules are less sensitive to high-temperature stress than pollen (Wahid et al. 2007). In previous studies, 38°C was most suitable for high-temperature 2n pollen induction in Populus (Kang et al. 2000a, Mashkina et al. 1989). Excessively high temperature inhibited pollen formation. Wang et al. (2012) reported that the most suitable temperatures for 2n megaspore production were 41°C to 44°C, which was higher than that for 2n pollen induction. This suggests that megasporocytes have higher tolerance to high temperatures than microsporocytes in Populus. In this study, not only did 38°C treatments produce many seeds, but also triploid production was relatively high, which suggests that development stage is more important than temperature for 2n female gamete production.

Occurrence of 2n-gametes seems to be controlled genetically, but expression of these genes is influenced greatly by the environment (Ramanna and Jacobsen 2003). The mechanism of 2n gamete formation was reviewed by Veilleux (1985) and Bretagnolle and Thompson (1995). Polyploids of meiotic doubling resulting from first-division restitution (FDR) and second-division restitution (SDR) were different in genetic composition and breeding value. Theoretically, 2n gametes formed by FDR transmitted approximately 80% of parental heterozygosity to polyploid offspring, whereas SDR transmitted approximately 40% (Mendiburu and Peloquin 1977). Consequently, FDR gametes are particularly valuable in plant sexual polyploidization breeding programs (Bretagnolle and Thompson 1995, Ortiz and Peloquin 1994, Ramanna 1983). In the study of Wang et al. (2012), not only FDR 2n megaspores but also SDR 2n megaspores were produced by high temperature treatment, which generated offspring with different heterozygosity. However, in our study, triploid plants were obtained only in first meiosis division and this mode of 2n female gamete formation is genetically equivalent to the FDR mechanism. Compared with 2n female gametes induced by high temperature exposure during megasporogenesis, 2n eggs induced by high temperature exposure during the development of embryo sacs should be completely homozygous, due to their origin in mitotic inhibition. Different heterozygosity of triploid hybrids can have great value in the breeding program of P. Adenopoda and these protocols can be applied for the quick induction of artificial polyploids. Future studies will be necessary to investigate the heterozygosity of triploid offspring through molecular analysis and observe the performance of triploid offspring in the field.

We thank Dr. XuJun Wang from Forestry Research Institute of Hunan province for collecting the plant material and for additional help. This research was financially supported by the Forestry Public Benefit Research Foundation (20100400900-3).